阐述行为主义心理学在游戏行业十年发展状况

作者:John Hopson

一个孤独的科学家在自己的实验室一直工作到深夜,不断地组装着自己的创造物,然后面向全世界发行这一富有影响力的作品!

他并不是一个科学怪人,他只是在研究行为游戏设计!

当我在十年前撰写那篇文章时,我还是一名心理学研究生,并且也是一名从未真正接触游戏产业的业余游戏设计师。但是不可否认的是,那篇文章对于整个网络来说的确是一个非常特别的存在。随后它被翻译成多种语言版本,甚至被当作学生们的研究内容。不仅被各种学者所引用,还出现在了《赫芬顿邮报》和《Cracked》(游戏邦注:美国最畅销的漫画杂志)上。

而今天,作为那篇文章发表10周年纪念日,我更是有必要对这一主题进行反思。自从2001年以来,整个游戏产业发生了巨大的变化,而我想在此重新思考这过去十年的发展是如何慢慢背离之前文章提要的要点。

强化学习被公认为游戏设计中的一个强大力量。

这十年来最大的变化莫过于,如今我们已经难以找到不重视内部奖励结构的游戏。十年前,那种认为游戏是否包含奖励机制,以及这些奖励的分配方式将影响玩家游戏体验的说法很荒谬。但现在看来,奖励已经成为游戏中一种理所当然的内容。

增强(Reinforcement,又称强化)已经被游戏设计所接纳的一个明显例子就是成就系统的广泛使用。成就系统是一种非常有趣的研究案例,因为除了成就本身之外,游戏实际上并没有提供什么实质的奖励。像《魔兽世界》等游戏便是通过使用成就系统而引导玩家尝试其他游戏模式,如探索或PvP模式。我也认为,帮助玩家在他们所接触的游戏中找到更多乐趣便是一种强化运用的表现。

Facebook等平台上社交游戏的崛起也说明了强化已成为游戏产业中不可忽视的一大核心要素。的确,早前的这类型游戏基本上是用图像去呈现出强化元素。而游戏的简单性也让人们很容易就明白其受欢迎的原因。

其中包括三大要素:组织有序的奖励机制,强大的病毒式传播渠道以及易用性。它们的成功也意味着别人不能再轻易贬低这些力量。随着社交游戏间的竞争日趋激烈,这类型游戏虽然变得更加复杂,但比起其他游戏类型,它们的行为对刺激的附带性(Contingency)则多停留于表面。

成功地在游戏中使用这种附带性也能够帮助我们更好地明确如何在游戏之外的领域运用这些元素,例如医疗健康、安全驾驶等。“游戏化”的确与游戏没有多大关系,而是与附带性更有关联。虽然我们不是很理解为何要借游戏这种轻松的娱乐领域,让人们严肃对待严肃事件中的奖励结构,但是我们也很庆幸这种现象最终还是成了现实。

除了行为心理学,游戏中的所有心理学话题都成了主流趋势。我看过许多关于心理学与游戏互动这一话题的博文,甚至有一些工作室还拥有自己的全职心理学家。

支持者和批评者都夸大了这种技巧的影响力。

尽管这些技巧的确具有科学原理,并且也确实有效,但是它们并不是游戏设计宝典。传统行为心理学是研究特定心理过程的良好、简单模型,但是它却不能解释所有的人类行为。所以现代心理学不只包含行为主义也是有原因的。

支持者与批评者双方都出现了过份强调这些技巧影响力的倾向。从“支持者”的角度来看,很多游戏开发者都认为乐趣并不重要,他们只是想要创造出一个奖励结构。但是最终却证实这种想法是错误的,因为他们面临的竞争对手是其它兼具乐趣与奖励结构的游戏。附带性与华丽的图像和音效一样对游戏非常有帮助,但是游戏所需要的却不只如此。

从批评者的角度来看,很多人都认为强化程序太过强大,违背了玩家在游戏中的真实意愿。并且虽然强化程序非常有效,但是却不足以体现人的所有心理反应或游戏体验。

就像在咖啡店中使用会员卡——这是现实生活中的一种附带强化。的确,这比游戏中的附带性强大多了,因为它将提供实质的现实利益。但是我想一般人都不会认为“买10杯拿铁,1杯免费”的优惠过于操纵性或诱惑性而让一般人难以抵抗吧。

附带性始终存在。

在Warson明确了行为主义这一定义后的近一个世纪,人们还在误解其含义。很多人都认为游戏中并不存在附带性,除非是人为强加于此。这种观点当然是错的。如果你在玩游戏,你肯定能够从中获得相关奖励。

这与奖励是具有内在属性(自我表现)还是外在属性(作为一种成就)无关。如果玩家发现游戏中不存在任何奖励,他们便不会玩游戏。奖励的呈现方式正是行为心理学所描述的一种附带性。无论游戏设计师是否意识到了这一点,奖励终究是存在的。

我在之前的行为游戏设计文章曾指出:

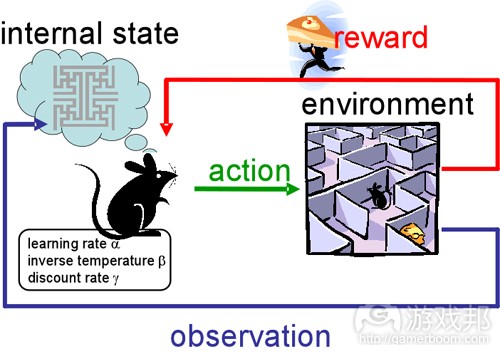

“每款电脑游戏都会让玩家以某种方式做出反应。心理学可以提供框架和术语,以便我们理解自己正在告诉玩家何种内容。”

不幸的是,很多人都还认为附带性是一种人为“添加剂”:就像添加于电子游戏中的“味精”。这种看法并不正确。附带性是游戏中的根本内容,并且我也不确定如果一款“游戏”不具备任何附带性,它还能不能称得上是“游戏”。

这里并不存在“斯金纳箱”。

除此之外,当那些批评者将游戏当成是“斯金纳箱”(游戏邦注:新行为主义心理学的创始人之一的斯金纳为研究操作性条件反射而设计的实验设备,最终证明了操作性条件反射理论)时,他们其实并不理解什么是“斯金纳箱”。早前的行为主义者的目标并不是创造一个人为环境去研究一些新的精神控制形式,他们只是希望创造出一个关于现实世界的简化模式。

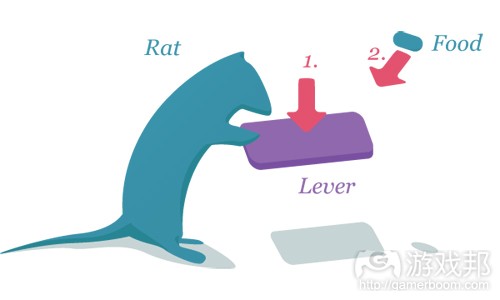

他们正是通过创造一个最简单的操作性学习任务(即“按压杠杆,获得食物”)而在一个基本层面上更好地理解学习内容。与所有的科学实验一样,这也是一种关于分离现象的尝试,能够消除那些混淆研究的各种解释。

而创造这种操作性条件则并不需要“斯金纳箱”。这只是一种关于研究条件作用的实验工具。我们没有理由将“玩家置于斯金纳箱中”!

道德

在游戏设计中运用行为主义的道德伦理仍是备受争议的谢话题(游戏邦注:请点击阅读相关文章《从条件反射行为反思游戏设计的道德问题》)。行为游戏设计被称为是“令人毛骨悚然的行为”,“让人不安的做法”,甚至可能造成上瘾等负面影响。

对于我来说,所有的这些讨论的出发点便是关于附带性始终存在于游戏中,而强化学习元素则是随着游戏的发展而发展。游戏设计师并不能完全理解心理学元素,但是他们却孜孜不倦地在利用这些原理创造游戏机制。在人们开始创造变化率时间表之前,开发者们始终坚持在游戏中设置随机战利品。我们必须清楚的是,附带性是游戏的本质,它们会塑造玩家行为。

设计师必须始终对他们所创造的奖励系统和它所引起的结果负责。而这就意味着道德游戏设计要求设计师必须正视他们所创造出的附带性类型。

同时还需要注意的是,如果批评者认为奖励结构具有破坏影响的想法是正确的,那就更能说明附带性越是强大,游戏设计师就越需要负起责任去设计好游戏。

在我看来,如果设计师认为玩家能够从游戏的附带性中感受到更多乐趣,那么这种设置附带性就是道德行为。你必须确保游戏首先能够提供基本的娱乐价值,才能植入符合道德伦理的奖励以强化玩家游戏体验。

附带性具有较大的结构,是一个由原子行动和奖励所构成的分子。而不论是行动还是奖励都必须具有乐趣,如此才能确保游戏中的附带性具有道德性。如果设计师只是在游戏中随机设置成就系统,并以一种无趣的方式给予玩家奖励,这只会破坏原本优秀的游戏设计。总之,只有当设计师能够真正理解游戏中的附带性,他们才能创造出真正有趣的游戏。

未来的发展

最后,我认为这一话题的现状便是,它只能用于概括早期心理学的内容。在行为主义出现之前,心理学是一个极端主观的领域,主要是受到人们的观点和反思所驱动。而激进的行为主义者则会对此出现过度反应,拒绝承认外界观察者能够客观地衡量人们的任何心理状态。

很明显,这种激进的反应是错误的,但是他们对于可证实数据的重视以及对奥卡姆剃刀原理(游戏邦注:由14世纪逻辑学家,圣方济各会修士奥卡姆的威廉提出,可以归结为:若无必要,勿增实体。)却做出了重要贡献,并成为现代心理学中不可分割的重要部分。虽然激进行为主义过度简单,但是它却为今后更复杂的原理(如认知心理学)的发展奠定了基础。

我认为在游戏界中亦是如此。今天我们主要关注的是游戏中的奖励,投入机制,成就以及游戏化,但是过几年后,我们关于游戏产业的讨论话题可能又会发生变化,不过不管怎么变化,我们的游戏设计总在朝着实证研究法的方向迈进,我们的玩家也能够真正从中受益。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

10 Years of Behavioral Game Design with Bungie’s Research Boss

by John Hopson

A lone scientist labors late into the night in his lab, assembling his creation piece by piece, and then releases it to rampage across an unsuspecting world! Muwhahahaha!

No, not Frankenstein. Behavioral Game Design!

When I wrote that article a decade ago, I was a psychology graduate student and amateur game designer who had never worked in the games industry. Since then, the article has run amok, living an almost completely independent existence in the wilds of the internet.

It’s been translated into multiple languages and assigned as homework. It’s been cited by academics, pilloried by the Huffington Post, and even lampooned by my childhood favorite, Cracked magazine.

[Footnote: This actually makes me the second of Bungie's employees to be called out by Cracked. Their treatment of our security chief was much more complimentary.]

And as anniversaries tend to do, the 10 year anniversary of this article has spurred a lot of reflection on my part. The industry has changed almost beyond recognition since 2001, and I’d like to take the opportunity to ruminate publicly about where this topic has gone in the past decade.

Reinforcement learning has been acknowledged as a powerful force in game design.

The biggest change is that it’s hard to find a game today that doesn’t take its reward structure seriously. At the time of the article, it was a radical idea to say that games contained rewards and that the way those rewards were allotted could affect how people played. Now it’s simply a given.

The clearest example of the acceptance of reinforcements in game design is the widespread use of achievements. Achievements are a really interesting case for study because there often isn’t any tangible reward past the achievement itself. Some games, such as World of Warcraft, have used achievements to direct players towards alternate modes of play they might find more fun, such as exploration or PvP. In my eyes, helping players find more fun in the games they’re already playing is one of the best uses of reinforcements.

The rise of social games on Facebook and elsewhere is another great example of how reinforcements have become a central topic in the games industry. Indeed, the early pioneers of this genre were basically reinforcement schedules with graphics. Their simplicity made it impossible for anyone analyzing them to misunderstand what made them so popular.

They had only three ingredients: well-structured rewards, strong viral communication channels, and high accessibility. Their runaway success has meant that no one will ever discount the power of those factors again. As competition among social games has grown, they’ve become much more sophisticated, but their contingencies still lie closer to the surface than in most genres.

The successful use of contingencies in games has also led to a reexamination of how they can be applied outside of games, on topics from fitness to encouraging safer driving.

“Gamification” really has nothing to do with games and everything to do with contingencies. It’s a little baffling that it took a fluffy entertainment field like games to make people take reward structures seriously on more serious topics, but it’s nice that they are finally doing so.

Beyond behavioral psychology, the whole topic of psychology in games has gone mainstream. There are entire blogs devoted to studying how psychology and games interact, and some studios even keep full-time psychologists on staff.

The power of these techniques has been radically overstated by both enthusiasts and critics.

While the science underlying these techniques is true and the techniques do work, they are not the Philosopher’s Stone of game design. Classic behavioral psychology is a nice simple model of certain basic mental processes, but it falls down when trying to explain the totality of human behavior. There’s a reason why modern psychology consists of more than just behaviorism!

The over-emphasis on these techniques has been seen on both sides. On the “enthusiast” side, a number of game developers have assumed that fun didn’t matter; they just had to have a reward structure. This has generally proven untrue, since they are competing against other games that are both fun and have a good reward structure. Good contingencies are helpful to a game, just as good graphics or good music is helpful, but not sufficient.

On the critical side, there have been plenty of claims that reinforcement schedules are too powerful, that they compromise the will of the player. Again, reinforcement schedules are useful and effective, but don’t represent the total sum of human psychology or the game experience.

Consider the use of loyalty cards at a coffee-shop. It is a contingency, exactly like the game contingencies covered in the original article. Indeed, it should be more powerful than game contingencies because it provides tangible real world benefits. And yet I don’t think anyone would argue that “buy 10 lattes, get 1 free” is manipulative or too powerful for the average person to resist. (The chemical properties of caffeine notwithstanding.)

Contingencies always exist.

Nearly a century after Watson defined behaviorism, it’s still misunderstood. Many people seem to assume that there are no contingencies in a game unless they’re explicitly added. This is simply wrong. If you’re playing a game, there’s something in there that’s rewarding for you.

It doesn’t matter if the reward is intrinsic (self-expression) or extrinsic (an achievement). If the player doesn’t find something rewarding in the game, they don’t play it. Any pattern in how that reward is provided is a contingency of the sort described by behavioral psychology. They exist whether or not the designers are aware of them.

The original Behavioral Game Design article was fairly clear about this:

“Every computer game is implicitly asking its players to react in certain ways. Psychology can offer a framework and a vocabulary for understanding what we are already telling our players.”

Unfortunately, many people still believe that contingencies are some sort artificial additive: MSG for video games. This just isn’t true. Contingencies are fundamental to games, so much so that I’m not sure it’s possible for something to qualify as a “game” without at least one contingency.

There is no Skinner Box.

Furthermore, when critics of this approach describe games as Skinner Boxes, they completely miss the point of the Skinner Box. The goal of the early behaviorists was not to create an artificial environment where some new form of mind control could happen; it was to create a simplified model of the real world.

It was an attempt to understand learning at a fundamental level by creating the simplest possible operant learning task: “Press lever, get food.” Like all scientific experiments, it was an attempt to isolate a phenomenon, to remove distractions and alternative explanations that could confuse the issue being studied.

A Skinner Box is completely unnecessary to create operant conditioning. It is an experimental tool for studying conditioning, nothing more. There wouldn’t be any point to “putting players in a Skinner Box”!

Ethics

The ethics of applying behaviorism to game design are still very much a subject of debate. Behavioral Game Design has been called “creepy”, “freaking disturbing”, and accused of promoting addiction.

For me, the starting place for this discussion has to be the fact that contingencies always exist and reinforcement learning is always going on. Game designers can be completely ignorant of the psychology involved while still creating mechanics that draw on these principles. People had been making games with random loot drops for years before anyone pointed out that they were creating variable ratio schedules. Contingencies are the essence of games, and those contingencies shape player behavior.

The designer is responsible for the reward system they create and its consequences. In my opinion, this means that ethical game design requires the designer to consider the sort of contingencies they are creating.

Note that this would be even more true if the critics were correct in thinking that these reward structures are a subversive influence. The more powerful these contingencies are, the more seriously game makers should take our responsibilities to design them well.

In my personal view, contingencies in games are ethical if the designer believes the player will have more fun by fulfilling the contingency than they would otherwise. You have to believe in the fundamental entertainment value of the experience before you can ethically reward players for engaging in that experience.

Contingencies are a larger structure, a molecule made up of atomic actions and rewards. Both the actions and rewards must be genuinely fun things for a game contingency to be ethical.

Designers often toss achievements semi-randomly into their games, rewarding players for playing in a way that’s fundamentally unfun and sabotaging otherwise fine game design. This was actually the entire point of the original article — the idea that designers who understand their contingencies will produce games that are more fun.

The Future

Finally, I think the most hopeful thing about the current state of this topic is the way that it is recapitulating the early history of psychology. Before behaviorism, psychology was an extremely subjective field, driven primarily by opinion and introspection. The radical behaviorists represented an overreaction to that, refusing to acknowledge any aspect of the mind that couldn’t be measured objectively by an outside observer.

The radical position was obviously wrong, but its focus on provable data and its profound commitment to Occam’s Razor were effective and useful and have become permanent parts of modern psychology. Radical behaviorism was overly simplistic, but it laid necessary groundwork for later, more complex approaches such as cognitive psychology.

I believe that something similar is happening in games. Right now, there is an overemphasis on this topic. We talk a lot these days about rewards and investment mechanics, achievements and gamification. In a few years, the industry will move on and the topic will be taken for granted, but we will have permanently shifted towards a more empirical approach to game design, and our players will benefit from that.(source:GAMASUTRA)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号