分析“女孩游戏运动”及其产品没落的原因

作者:PATRICIA HERNANDEZ

在整个游戏产业中,公司没落并不是什么新鲜事。但是对于Brenda Laurel来说,这却是切身之痛。

Purple Moon花费了6年的时间以及4千万美元于对许多孩子进行调查,并创造出8款游戏。早在1996年,当人机互动领域先驱Brenda Laurel成立了Purple Moon这家公司时,这些孩子们在游戏领域还没有什么发言权。

小男孩已经是电子游戏的常客,也成了诸多游戏开发公司的主要目标用户。

那么小女孩呢?

不断有研究证明女性群体普遍不喜欢技术性内容,或者游戏。

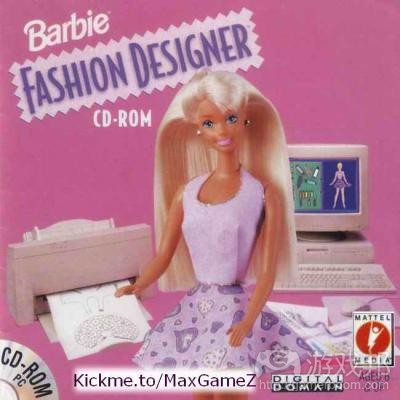

但是“女孩游戏运动”的兴起,像《芭比娃娃时装设计师》以及Purple Moon的《Rockett Movado》系列游戏相继登上销售排行榜首位等现象都证明了这是个错误的观点。所以说女孩们也喜欢游戏。

尽管如此,像Purple Moon等拥护这些运动的大多数公司都相继没落了。但是关于这一运动所引起的问题——即是否有必要推出“面向女孩的游戏”,或者“女孩游戏”在定义仍然是今天游戏产业中备受争议的焦点(尽管现在的社会已经更具性别包容性)。

当Laurel在1995年决心开始创造面向女孩的游戏时,她对此报以了极高的期望。游戏是一种产品导向型产业,而Laurel的个人方向则是进行“文化工作”。她并不想创造一款迎合高管们喜欢的游戏,相反地,她希望能够通过游戏积极吸引并鼓励所有的年轻女性,引导着她们参与社交活动,融入各种文化并热爱游戏故事,同时创造出拥有共同价值观且知识面广泛的文化载体。但是事实上,她在游戏产业中看到的多是一些关于数字大爆炸的产物。

Laurel的看法是更具包容性的行业将更为进步,而与此同时它也将成为各种女孩爱上技术性内容(游戏邦注:这是女性领域中所缺少的元素)并走向科技的通道。

社会责任感并不是一种赚钱的工具,它也绝对不会推动股票价格的上涨。Laurel在自己的著作《Utopian Entrepreneur》中写道,当她提出游戏不应该只是充满射击和打斗内容时,便意识到自己很有可能失去工作。但Interval Research Corporation公司给予了Laurel新的机会(以及资金)去创造她理想中的非男性化游戏。

而正是在这种环境下才促成了Purple Moon以及“女孩游戏运动”的诞生。

20世纪90年代的掌机游戏市场中已经充斥着90%的美国男孩,并因此达到了饱和状态。与此同时,因为那时的计算机游戏还未被世嘉,任天堂或索尼所独霸,使其成为Laurel心目中的最佳拓展目标。让女孩去购买掌机是是个大考验,而如果是电脑的话就容易多了,因为一般情况下女孩家里应该都有一台电脑。而这时候Laurel需要做的便是找出女孩们真正感兴趣的内容是什么。

Purple Moon在调查中提到的问题非常直接:为什么女孩不玩游戏?我们该为她们创造何种游戏?以前许多尝试着去攻占女性市场的游戏总是假设:女孩显然喜欢彩虹,独角兽,粉色之类的内容。但是当这些游戏相继失败后,开发公司便开始认为女性市场不具有任何可盈利性。

尽管同样是假设,但是“女孩游戏运动”中的“粉色”游戏部门却获得了成功。这种“粉色”游戏包括大受欢迎的《芭比娃娃时装设计师》——它主要以传统的女性价值观,即对于外表的重视为基础。《芭比娃娃时装设计师》是该年度最畅销游戏之一。

Purple Moon便是这一运动的“紫色游戏”的重要组成部分,即主要面向与小女孩们进行交流,并研究她们真正感兴趣的内容。该公司的理念是通过人种学和社会学原理研究那些小女孩们真正关心的事物——而不是现实中人们想当然的结果。这便超越了传统意义上的调查——其调查是对于女孩的日常生活的了解。这是关于定性信息的混合体,如什么样的事物才能带给女孩安全感;以及定量信息的混合体,如她们看电视的频率是多少。

但是这种方法却备受争议。因为当你问小女孩她们真正感兴趣的是什么时,她们可能会回答人气,绯闻,物质主义,嫉妒,欺骗,口红,归属感或者独占性等内容——而不一定会牵扯到女权主义这一话题。

而Laurel所创造的游戏便是将价值观放在最前方。她的游戏总是围绕着各种选择而展开,并让女孩们在此思考她们希望自己在现实世界中成为怎样的人。因为游戏总是涉及到她们的日常生活,所以这也是一种“情感复述”。

而这种带有价值观的游戏也比较能够获得家长的认可,这些家长也并不确定游戏是否真的能够教授给孩子们有意义的内容。在《Utopian Entrepreneur》中Laurel解释了一大重要的设计指令,即确保游戏中不会出现任何强迫女孩执行“正确”任务的设置。因为对于任何女孩游戏来说这种强迫性设置都是一大危害,过于规范化的约束将不利于女孩在游戏中的行动。

但是关于“女性游戏”这一理念本身也存在一定的问题。

我们主要针对的是何种类型的女性?并不是所有女性都是相同的。这也并不是说女孩不会喜欢这项研究领域之外的内容。而且,各种研究也表明女孩并不是不喜欢暴力,只是更青睐于那些故事性强,角色个性鲜明的游戏。这真的是问题所在吗?如此便能够帮助我们更好地传达性别差异吗?

Brenda惊讶的发现自己竟然遭受到游戏评论者的强烈抨击——这些评论者认为《Rockett Movado》是一款糟糕的游戏同时带有强烈的女权主义思想,并且他们也不认为女孩游戏就是Purple Moon所创造的那样。但游戏的目标对象,也就是那些小女孩们都非常喜欢这款游戏。看来只有成人才乐于对“女孩游戏”的含义争吵不休。

Laurel在回顾Purple Moon时写道:“尽管一直在努力创造一些具有积极社会意义的内容,但是《Utopian Entrepreneur》的理念却让我陷入了无尽的职责与批评中。”

而深入研究“性别化游戏”的细节内容更是一种恶梦。研究只会不断地呈现一些相同的内容:男孩“更喜欢”暴力,竞争,权利与成功,而女孩则更喜欢协作,故事,特性描述,以及强调人与社会动态关系的游戏。而在电子游戏之外的领域中也出现这此类研究结果。

乐趣并不是依照性别而定的,不是吗?乐趣就是乐趣!

毫无疑问,男性和女性也能够喜欢相同的游戏元素。研究之所以注重差异性,是因为各种设想都认为两性之间必定存在相互矛盾的差异。而只针对于强化原有观点的研究则更是错误的研究。根据《Beyond Barbie & Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives on Gender and Gaming》的研究,我们可以发现男女喜好之间的相似性远远多于两者之间的差别。

从传统上看,性别就是家长允许子女玩哪类游戏的天然判断标准。而随后的问题就是,游戏是否将为男女玩家呈现这种不同的游戏模式,或者是否将默认于这种两性拥有不同品味和兴趣的现实?而忽视了这些问题我便只能创造出一些老套且问题多多的性别化游戏。

直至今日这一问题仍然饱受争议。尽管现在的我们已经知道性别不再是决定男性和女性喜欢哪种游戏的唯一因素——情境更加重要。研究表明,决定男孩和女孩是否喜欢技术和游戏的关键时刻在于中学那段期间。所以比起性别,年龄更能够影响孩子们对于游戏的喜好。除此之外,更加广泛的游戏文化层面也将影响着女性是否愿意玩游戏——不论是她们所接触到的游戏市场营销还是她们玩游戏所处的空间。

最终,不管是“女孩游戏运动”还是Purple Moon都失败了。而对于Brenda,这个在该项目投入了巨大心血并设想了一个更具包容心且更加进步的未来的女性来说,这的确是件让人痛心的事。所以到最后,创造一款成功的产品的重要性还是打败了人文工作。Purple Moon逐渐走向没落,就像那些推崇“女孩游戏”的公司一样被希望能够垄断市场的美泰公司所收购。

比起专注于创造出更加优秀的游戏,这一运动更加侧重挖掘细分市场。

也许创造出针对于特定性别的游戏并不是什么大问题。也许我们真正需要关注的是游戏中的哪些元素能够迎合我们所追求的性别化,并确保这个产业能够创造出更多同时迎合男性和女性的游戏。

不管怎么样我们真正需要明确的是游戏产业中需要多种不同的声音支持不同类型的用户——无论这么做是有利于商业发展还是只是一种人道主义观点。而来自女性的声音正是其中必不可少的要素。然而我们却会发现,比起单纯由男性开发的游戏,许多由女性创造的游戏更能够同时迎合男女双方玩家的喜好。不幸的是,现在游戏开发产业中的女性人数不仅越来越少,同时女性离开这个产业的几率也远远大于男性。

不管Brenda Laurel的方法是否正确,这个产业都需要像她这种工作,即致力于打造更具包容性的游戏产业,用自己的力量改变世界。在如今的游戏产业中,大多数游戏仍然是面向于男孩和成年男性。女性玩家仍只是广泛分布于休闲、教育类游戏以及社交游戏等更加强调“女孩喜欢的内容”的领域,而这一领域却备受硬核玩家群体的鄙视。我们迫切需要改变这种现状。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

She Tried To Make Good Video Games For Girls, Whatever That Meant

BY PATRICIA HERNANDEZ

Companies fail all the time, but this, this was different. For Brenda Laurel, it was personal.

Logistically, Purple Moon amounted to six years and $40 million dollars spent on research where thousands of kids were interviewed, and eight games were produced. Prior to 1996, when the company was created by Brenda Laurel, a pioneer extraordinaire within human-computer interaction fields, these kids had no voice.

Millions of little boys across the country were highly visible within video game culture, making them the primary demographic for game development companies.

Little girls though?

Studies continually pushed the idea that women just didn’t like technology—or games.

The Girl Games Movement, which saw titles like Barbie Fashion Designer and Purple Moon’s own Rockett Movado series rising to the top of the sales charts proved everyone wrong. Girls liked games too.

Even so, Purple Moon—and most of the companies that arose around the movement—disappeared. The questions that the movement elicited, though—like whether or not ‘games for girls’ should even exist, or what ‘games for girls’ even meant—are still topics of heated discussion today, despite better gender inclusivity.

When Laurel set off in 1995 to create an industry that listened to little girls, she had high hopes, according to her field manual on socially positive work, Utopian Entrepreneur. Games were a product-driven industry, and Laurel’s personal directive was to do “culture work.” She didn’t want to make a game that would be popular in a room full of executives. She wanted to make a difference. She wanted to engage and nurture young women positively, address their social, cultural and narrative proclivities, to create popular culture that shaped values and informed citizenship. Instead, at the time, all she saw was an industry that liked making digital explosions.

The idea was that a more inclusive industry would be more progressive, yes, but also that games could function as a gateway for girls to become interested in tech fields—which are scarce on women.

Social responsibility is not lucrative though, and it definitely won’t drive stock prices up. In the book Utopian Entrepreneur, Laurel wrote that she would sometimes lose her job just for suggesting games could be more than shooting and fighting. It wasn’t until Interval Research Corporation gave Laurel a chance (and a lot of money) to dig her hands into the issue that the viability of a non-hypermasculine game was tested.

The conditions were just right for Purple Moon and the Girl Games movement.

In the mid 1990′s, the market, which had 90% of American boys playing console games, was saturated. Other markets had to be found, tapped into. Computer games, meanwhile, weren’t colonized by Sega, Nintendo or Sony—which left computers and CD-Roms, now reasonably ubiquitous, as an available market. Getting girls to buy consoles might be a stretch, but they probably already had computers in the household. The trick was finding something they’d be interested in.

The inquiries Purple Moon fielded in their research were straightforward: why aren’t girls playing games, and how can we make games for them? Previously, most attempts to court the elusive female market were imbued with assumptions: girls obviously like this and this (rainbows, unicorns, pink, etc). When games including these assumptions failed—there was literally a first-person shooter that moved at slower speeds than normal and had girls shooting marshmallows—companies would take that as evidence that there was no female market to have a stake in.

The “pink” games segment of the Girl Games movement managed to luck out despite working with similar assumptions. These games, like the highly popular Barbie Fashion Designer, were highly dependent on traditional values of femininity—addressing concerns about appearance, for instance. Barbie Fashion Designer was one of the highest selling games in the year it was released.

Purple Moon was a part of a “purple games” segment of the movement, which decided to just plain speak to little girls and see what they were interested in. The idea was to focus on the things that little girls actually cared about through ethnography and sociology—not what people thought they cared about. This meant going beyond surveys: the research followed the girls around, tried to get a sense of what their lives were like. It was a mix of qualitative information, like what made the girls insecure, and a mix of quantitative information, like how much television they watched.

This approach was controversial. Turns out, when you ask little girls what they care about, the subjects that come up are popularity, gossip, materialism, jealousy, cheating, lipstick, belonging, and exclusion. Not exactly the most feminist of subjects.

What Laurel created was a game that put values at the forefront. The game centered on choice and asked girls to think about what type of person they wanted to be in the real world. Since the game dealt with their day-to-day lives, it functioned as a type of ‘emotional rehearsal.’ Games with values were met with some concern by parents, who weren’t sure if they should trust a game to teach kids about that sort of thing. In Utopian Entrepreneur Laurel explains that one of the important design mandates was to make sure that she didn’t create a game where the ‘right’ choice told girls how they should behave. This was the danger of having games for girls—they could be a too prescriptive in how girls should perform their gender.

The idea of games “for girls” in and of itself seemed problematic, too.

What type of girl are we talking about, exactly? Not all girls are the same. It’s not as if girls can’t like things outside of what research showed, either. Then again, all the research said was that it wasn’t that girls disliked violence, they just tended to prefer strong stories and well-written characters and were more likely to stick with a game that provided that for them. Is that really so problematic? Did it help essentialize gender?

Brenda was surprised to find herself under fire from both game reviewers, who thought Rockett was a bad game and feminists, who didn’t think games for girls should look like what Purple Moon created. Meanwhile, the little girls themselves, the ones that the games were actually made for? They tended to like the game. It was the adults who were bickering over the implications of “games for girls.”

“By trying to do anything socially positive at all, the utopian entrepreneur opens herself up to the endless critique that she is in fact not doing enough,” Laurel wrote in a retrospective on

Purple Moon.

Delving into the specifics of ‘gendered play’ is an even deeper nightmare. Research kept showing the same thing: boys ‘preferred’ violence, competition, power fantasies and winning, whereas girls liked cooperation, narrative, characterization, and games that focused on the relationships between people and social dynamics. These findings were reinforced outside of the context of video game research, too.

Fun isn’t gendered though…is it? Fun is fun…! Right?

Both genders are capable of liking the same elements of games, to be sure. Research likes to focus on differences, because the assumption is that there must irreconcilable differences between the genders. Research that is conducted solely to reinforce pre-existing ideals is problematic, though. Taking a closer look reveals that the overlap between what both genders like is bigger than the difference, according to a long series of research papers presented in the book Beyond Barbie & Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives on Gender and Gaming.

Historically, however, gender has determined how ‘play’ manifests itself for little boys and girls just by nature of what boys and girls tend to be allowed to do by parents. The question, then, is whether or not games take it upon themselves to challenge these modes of play, or whether they should acquiesce to an alleged reality where genders have specific existing tastes and interests (though they are fluid, and they don’t exist because of some intrinsic biological mandate,). Ignoring that we are socialized to perform gender in certain ways can be just as dangerous as enforcing problematic gender stereotypes.

This is all still widely disputed. What we know now, though, is that gender isn’t the sole determinant of what games men and women like—context matters. Research shows that the most pivotal moment for kids, which determines how invested boys and girls are with technology and games, is around middle school. Age can be a bigger influence in what people like in games than gender as well. Wider aspects of games culture can affect whether or not women play games, too—from the marketing games sell themselves with, to the spaces in which games are played.

Ultimately, the Girls Game Movement and Purple Moon failed.

For Brenda, who had invested so much of herself in the project, who envisioned a more inclusive, progressive future that she would pioneer, this was heartbreak. In the end, creating a successful product trumped humanistic work, as it always tends to. Purple Moon didn’t perform to expectations, and ended up like many other companies that made “games for girls” — purchased by Mattel, who

wanted to keep a monopoly on the market. The many retrospectives on that period of time make it clear that Laurel still looks back on this time wistfully, with much melancholy.

The movement itself was too focused on what made its games niche, and not what made the games good.

Perhaps it should have never been a matter of designing games that focus on a specific gender. Perhaps what was really needed was cognizance and accountability of what elements of a game may speak to gendered aspects we are socialized for, and to make sure the games the industry produces include something ‘for’ both genders.

Regardless, what was made clear was that the gaming was in dire need of different voices that spoke to different audiences—both because it’s good for business, and because it’s the ‘humanistic’ thing to do. Female voices are but one of the possible voices to include. Still, games made by women tend to perform well with both men and women alike, unlike games made solely by men.

Unfortunately, not only are there less women in the development side of games, but women are much more likely to leave the industry than men are.

Whether or not Brenda Laurel had the right approach is debatable. The need for her type of work, which aimed to create a more inclusive games industry, as well as a desire to make a difference in the world, is still sorely needed. Most games still cater to a primarily to boys and men. The markets in which female gamers are the most present in—casual games, educational games, social games—and the types of games that emphasize ‘what girls like’ are highly denigrated by the hardcore crowd. That needs to change.(source:kotaku)

上一篇:论述杰出游戏作品的9大必要元素

下一篇:开发者谈手机应用的8个推广方式

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号