游戏设计课程之游戏定义及制作实例(1)

作者:Ian Schreiber

综述

很多研究领域都有几千年历史。但游戏设计的研究时间还不到10年。相比其他学科,我们能够总结的内容并不多。

但我们同时非常幸运。过去几年,概念写作和形式分析终于达到临界质量状态,理论和实际知识终于开始在大学课程中开设,或者至少像这样以20个课程的形式呈现。(请点击此处阅读本系列第2、第3、第4、第5、第6、第7、第8、第9、第10、第11、第12、第13、第14、第15、第16、第17、第18课程内容)

这样说并不公平,游戏设计领域其实有很多内容,有许多相关书籍。但这些大多用处不大,或者需要集中精力阅读,业内鲜有人士阅读这些内容。本课程的阅读内容都是业内常见的读物;很多专业设计师都非常熟悉。

本课程分成两部分。前半部分主要着眼游戏设计理论和概念。我们将掌握什么是游戏,如何将游戏概念分解成组合要素,什么促使游戏作品略胜一筹或略逊一筹。后半部分则探讨比较实际的内容,即如何创造优秀作品,游戏制作过程。学习此课程后,玩家就能够制作自己的作品,这就是理论的实际践行效果。

什么是游戏?

我之前的定义是:涉及冲突的有规则体验活动。但“什么是游戏?”这个问题要复杂许多:

* 首先,这是我的定义。当然这也是IGDA Education SIG所采用的定义。

业内还有许多同我相左的定义。这些定义很多出自经验比我丰富之人。所以这个定义还有值得探讨的地方。

* 其次,这个定义并没有涉及如何设计游戏,所以我们将从游戏组成要素(规则、资源、行为和故事等)角度讨论什么是游戏。我把这些叫做游戏的“形式要素”。

区分不同游戏也非常重要。以《Three to Fifteen》为例,你们大多没有听过或玩过这款游戏。其规则非常简单:

* 玩家:2人

* 目标:收集3个相加等于15的数字

* 游戏设置:首先在纸上写下数字1-9,选择首先进行体验的玩家。

* 继续游戏:轮到玩家时,选择未被其他玩家选择的数字。你可以控制这个数字,将其从数字列表中去除,在纸张的侧面写下这个数字,以此说明这个数字现在为你所有。

* 解决方案:若有某玩家收集到3个相加等于15的数字,游戏便终止。此玩家便成为赢家。若9个数字都被收集后,没有玩家胜出,游戏便是平局。

大家不妨尝试这款游戏,或同自己较量,或同其他玩家角逐。

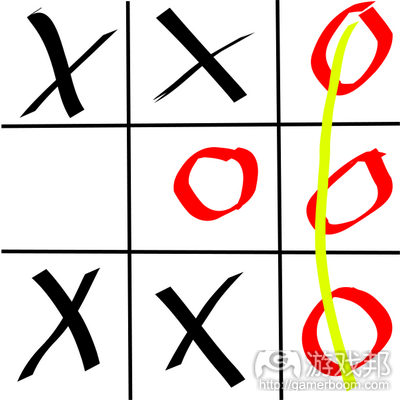

数字1-9可以3×3的网格模式呈现,也就众所周知的“纵横图”,其中每行、每列及每对角线的数字加起来都等于15:

现在你就心中有数。这就是一字棋游戏。那么一字棋和《Three to Fifteen》是大同小异,还是存在差异?(游戏邦注:这取决于你的定义)。

评论词汇

我所谓的“词汇”是系列供我们讨论游戏的词语。“评论”在这里并不是指我们非常吹毛求疵,而是说我们能够批判性地分析游戏。

词汇也许并不像你所设计的激光机器忍者那般有趣,但这非常重要,因为这是我们谈论游戏的方式。否则我们就只能用手比划,用嘴嘟哝,若无法交流,我们将很难学习东西。

谈论游戏一个最常见的方式是用其他游戏形容它们。“这就像《侠盗猎车手》混合《模拟人生》和《魔兽世界》。”但这存在两大局限性,首先,若没有体验《魔兽世界》,我就无法明白你的意思;这要求我得同时玩过这两款游戏。其次,更重要的是,这不适合游戏类型不同的情况。你如何基于其他游戏谈论《Katamari Damacy》?

另一常被创作游戏设计文本人士选择的方法是必要时候创造新术语,始终如一地应用于文本中。我可以这么做,这样我们至少能够互相沟通游戏设计的基本概念。这里的问题是课程结束后会出现什么情况;本课程的术语就会变得毫无用处。我无法要求或命令行业采用我的术语。

有人也许会问既然通过某些词汇讨论游戏如此重要,那为何我们至今依然没有这么做?为何游戏行业没有设定系列术语?答案是他们目前正在进行,这是个缓慢过程。未来阅读资料将出现许多这类词汇。

游戏和玩乐

玩乐的方式有许多种:传球,假扮,当然还有游戏。所以你可以把游戏当作一种玩乐方式。

二者怎么可能互为子集?这有些自相矛盾。在我们看来,这没有影响——这里的重点是游戏和玩乐是相互关联的概念。

那么什么是游戏?

你会发现我至今都还没有回答这个问题。这是因为这个概念很难定义,很难确保将所有游戏内容都囊括在内(游戏邦注:同时保证将非游戏内容排除在外)。

下面各种版本的定义:

* 游戏要有“目标和工具”:目标、结果和系列实现规则。(David Parlett)

* 游戏是包含玩家决策的活动,是在“有限环境”中寻找目标。(Clark C. Abt)

* 游戏包含六大属性:“自由”(体验具有选择性而非义务性),“单独”(事先设定于某空间和时间中),具有不确定的结果,“非创造性”(不会创造商品和财富),受规则限制,“虚构”(游戏不是现实生活,而是共享的独立“现实”)。(Roger Callois)

* 游戏是“自愿付出完成不必要的障碍。”这是最受大家认可的定义。这个定义听起来有些不同,但包含很多先前定义的概念:自发性,存在目标和规则。“不必要障碍”说明规则故意拖延效率——例如,若一字棋的目标是横向、纵向及对角方向收集3个符号,最简单的方式就是在首回合在同一行中写下3个符号,同时让对手无法接触到纸张。但你并没有这么做,因为游戏有自己的规则,这些规则是游戏体验的来源。(Bernard Suits)

* 游戏有4个属性。它们是“封闭而形式的机制”;包含互动;包含冲突;提供安全性,至少相比其所代表的实际内容(例如,真正的美国足球与以美国足球为蓝本的游戏)。(Chris Crawford)

* 游戏是“玩家进行系列决策,通过游戏符合合理管理资源,从而实现目标的艺术形式。”这个定义包含许多前面没有的内容:游戏属于艺术,涉及决策和资源管理,游戏有“符号”。此外,也涉及有常见的目标概念。(Greg Costikyan)

* 游戏是“玩家参与规则定义的虚拟冲突,进而产生量化结果的机制”(这里的“量化”是指存在“输赢”概念)。这个定义来自Katie Salen和Eric Zimmerman创作的《Rules of Play》一书中。书中还罗列上述系列定义。

通过讨论这些定义,我们现在握有探讨游戏的出发点。上述许多元素在很多游戏中司空见惯:

* 游戏是种活动。

* 游戏具有规则。

* 游戏包含冲突。

* 游戏具有目标。

* 游戏包含决策。

* 游戏是虚构内容,它们非常安全,脱离正常生活。这有时也指玩家进入“魔法阵”或共享“有趣心态”。

* 游戏无法给玩家带来物质收获。

* 游戏就有自发性。若你处在枪口下,被迫参与所谓的游戏活动,有人会认为这对你来说便不再是游戏(试着想想:若你认同这点,那么有些玩家自发参与,而其他玩家被迫参与的活动则既是游戏,又不是游戏,这取决于你所处的立场)。

* 游戏具有不确定的结果。

* 游戏是真实内容的再现或模拟,但其本身采用虚拟模式。

* 游戏缺乏效率。规则会融入限制玩家采用最便捷方式实现目标的障碍。

* 游戏包含机制。通常这是个封闭机制,这意味着资源和信息不会在游戏和外在世界间流动。

* 游戏是种艺术形式。

各定义的缺陷

上述哪个定义最准确?

没有任何一个定义完美无缺。若你企图自己定义游戏,其中也会存在不足。下面是些常产生定义问题的边缘情况:

* 益智游戏,如数字游戏《数独》、《魔术方块》或逻辑游戏。这些是否属于游戏?在Salen & Zimmerman看来,它们是游戏的一种,游戏包含系列正确答案。而Costikyan则认为,它们不属于游戏,虽然它们可以融入游戏中。

* 角色扮演游戏,例如《龙与地下城》。游戏名称就包含“游戏”一词,但其通常不被视作游戏(因为游戏没有最终结果或解决方案,没有输赢)。

* 《Choose your own adventure》系列书籍。这些通常不被视作游戏;你在“阅读”书籍,而不是“体验”书籍。但这几乎满足所有游戏定义的标准。更令人迷惑的是,若在其中某本书中添加某页包含数值的“人物统计表”,随机决定在某些页面中融入“技能检测”,将其称作“冒险模块”而非“Choose your own adventure”,我们发现这就变成游戏!

* 故事。游戏是否属于故事?一方面,多数游戏都呈线性发展,而游戏则更具动态。另一方面,多数游戏都蕴含某些故事或叙述内容;如今甚至还有投身数百万美元视频游戏项目的专业故事作家。除此之外,玩家还可以讲述自己游戏体验的故事。记住故事和游戏概念具有紧密关联。

制作游戏

你会好奇这些内容如何帮助你制作游戏。这并非一蹴而就,但我们需要首先先来看看某些共享词汇,这样我们能够以有意义的方式谈论游戏。

首先是关于游戏。很多同学都表示他们很担心自己能否制作出游戏。他们觉得自己缺乏创造性和技能等要素。这完全是废话,现在你将从我们的系统中把握这些技能。

若你之前有制作过游戏,完全无需有这样的担心。现在就来制作游戏。拿出纸笔。这只要15分钟,整个过程将非常有趣。

我们要制作的是所谓的瞄准终点的棋盘游戏。你可能玩过很多这类游戏;游戏目标是将自己的符号代表从棋盘某处移到另一处。常见例子包括《Candyland》、《Chutes & Ladders》和巴棋戏。这些是最简单的游戏类型。

首先,先画小路。可以是直线,也可以是曲线。然后延伸出不同分支。

其次,寻找主题或目标。玩家需要从路径一端走到另一端;为什么?因为你或朝某物靠近,或避开某物。玩家在游戏中是什么形象?什么是游戏目标?设计游戏时,一开始就弄清游戏目标帮助很大,很多规则都将基于此进行设置。你要能够在几分钟里想出些内容。

第三,你需要设定玩家在各空格中移动的规则。玩家要如何移动?最简单的方式是在轮到自己的时候掷骰子,出现什么数字,就移动多少步(游邦注:这个大家可能非常熟悉)。你还要决定游戏的结束方式:玩家是得掷出准确数字方能抵达终点,还是只要掷出的数字足以到达终点,就算获胜?

现在你已把握所有游戏要素,虽然这里还缺少某个常见要素:冲突。若能影响对手,或帮助他们,或伤害他们,游戏会更加有趣。想想玩家同对手的互动方式。当玩家与对手同处一个空格时,会出现什么情况?是否存在某些空格能让你影响游戏,如让他们前进或后退?轮到玩家时,他们是否能够通过其他方式移动对手(如掷出某数)?应融入至少一个能够让玩家修改对手身份的渠道。

现在你已成功制作出一款游戏,游戏虽算不上优秀,但至少功能齐全。而且只用几分钟完成,所用工具不过是纸和笔。

这个创造方式要归功于布伦达·布瑞斯韦特。

所获经验

若你未从此训练中收获什么,至少请记住一点:你可以在几分钟内制作出游戏。这无需编程技术,无需丰富创造性,大笔资金、资源或其他特殊材料。整个过程无需长达几个月,而只是着眼于某个简单构思,此构思只需用几张纸便能在较短时间内容完成。

深入更新内容和快速建模后,很多人会没有勇气投身设计工作,架构自己的构思。他们担心这会耗费过长时间,或者不如预期的那么好。这个过程涉及通过制作和体验自己的游戏,去除薄弱构思,将它们进一步强化。内容投入运作的周期越短,我们试验的机会就越多,游戏的效果就更好。若你利用超过几分钟的时间制作游戏首个模型,显然耗时过久。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Level 1: Overview / What is a Game?

By Ian Schreiber

Welcome to Game Design Concepts! I am Ian Schreiber, and I will be your guide through this whole experiment. I’ve heard a lot of excitement throughout all of the registration process these last few months, and be assured that I am just as excited (and intimidated) at this whole process as anyone else. So let me say that I appreciate your time, and will do my best to make the time you spend on this worthwhile.

Course Announcements

Before we begin, I’d like to get a few quick administrative things out of the way:

* Registration. As I’m writing this, there is a large backlog of registrations sent in at the last minute. So, if you sent an email and have not yet received a reply, check your inbox in the next day or two. If you still haven’t received a response by Wednesday, it means I did not receive your email and you should find your previous one and forward it. Double-check the email address: gamedesignconcepts@yahoo.com

* On that subject, keep in mind there are over a thousand people actively participating here. I value all of your feedback and contributions, but if you send an email directly to me, understand that I may receive a lot and it may take some time to get back to you.

* I’ve set up two resources for this course, a wiki and a blog.

* The wiki is at http://gamedesignconcepts.pbworks.comand is intended for two things: as a resource for group collaboration (for those of you who are taking this course with friends), and as an area for people to post translations of this blog into other languages (as some of you have offered). If you think of other uses, feel free! Right now it is a closed wiki and requires an email address and password. If you registered, expect to receive an email in the next few days giving you login information.

* The discussion board is at http://gamedesignconcepts.aceboard.com and is the primary place for interactive discussion. I’ve created separate discussion areas by interest group (such as: an area for college students, another for professional educators, another for professional video game designers, and so on). I will create forums by geographic region soon, to allow you to find others in your area and arrange to meet in person, if you’d like. This is also where you’ll be able to post the work you do for this course, and give and receive peer review (these will become available as they are assigned). Lastly, there is a forum at the top called Meta Discussion, which is discussion for the course itself — what is working and what is not, in terms of using blog, wiki, forum and so on in order to communicate. You will have to create an account and then wait for the moderator to add you. This process may take a couple of days, so please be patient.

* If you twitter, use the tag #GDCU for any course-related tweets.

* If you have something to say about the course content itself, feel free to leave it as a comment here on this blog.

And with all of that out of the way, let’s talk about game design!

Course Overview

Most fields of study have been around for thousands of years. Game design has been studied for not much more than ten. We do not have a vast body of work to draw upon, compared to those in most other arts and sciences.

On the other hand, we are lucky. Within the past few years, we have finally reached what I see as a critical mass of conceptual writing, formal analysis, and theoretical and practical understanding to be able to fill a college curriculum… or at least, in this case, a ten-week course.

Okay, that isn’t entirely fair. There is actually a huge body of material in the field of game design, and many books (with more being released at an alarming rate). But the vast majority of it is either useless, or it is such dense reading that no one in the field bothers to read it. The readings we’ll have in this course are those that have, for whatever reason, pervaded the industry; many professional designers are already familiar with them.

This course will be divided, roughly, into two parts. The first half of the course will focus on the theories and concepts of game design. We will learn what a game is, how to break the concept of a game down into its component parts, and what makes one game better or worse than another. In the second half of the course, the main focus is the practical aspect of how to create a good game out of nothing, and the processes that are involved in creating your own games. Throughout all of the course, there will be a number of opportunities to make your own games (all non-digital, no computer programming required), so that you can see how the theory actually works in practice.

What is a game?

Those of you who have read a little into the Challenges text may think this is obvious. My preferred definition is a play activity with rules that involves conflict. But the question “what is a game?” is actually more complicated than that:

* For one thing, that’s my definition. Sure, it was adopted by the IGDA Education SIG (mostly because no one argued with me about it). There are many other definitions that disagree with mine. Many of those other definitions were proposed by people with more game design experience than me. So, you can’t take this definition (or anything else) for granted, just because Ian Says So.

* For another, that definition tells us nothing about how to design games, so we’ll be talking about what a game is in terms of its component parts: rules, resources, actions, story, and so on. I call these things “formal elements” of games, for reasons that will be discussed later.

Also, it’s important to make distinctions between different games. Consider the game of Three to Fifteen. Most of you have probably never heard of or played this game. It has a very simple set of rules:

* Players: 2

* Objective: to collect a set of exactly three numbers that add up to 15.

* Setup: start by writing the numbers 1 through 9 on a sheet of paper. Choose a player to go first.

* Progression of Play: on your turn, choose a number that has not been chosen by either player. You now control that number. Cross it off the list of numbers, and write the number on your side of the paper to show that it is now yours.

* Resolution: if either player collects a set of exactly three numbers that add up to exactly 15, the game ends, and that player wins. If all nine numbers are collected and neither player has won, the game is a draw.

Go ahead and play this game, either against yourself or against another player. Do you recognize it now?

The numbers 1 through 9 can be arranged in a 3×3 grid known as a “magic square” where every row, column and diagonal adds up to exactly 15:

Now you may recognize it. It is the game of Tic-Tac-Toe (or Noughts and Crosses or several other names, depending on where you live). So, is Tic-Tac-Toe the same game as Three-to-Fifteen, or are they different games? (The answer is, it depends on what you mean… which is why it is important to define what a “game” is!)

Working towards a Critical Vocabulary

When I say “vocabulary” what I mean is, a set of words that allows us to talk about games. The word “critical” in this case does not mean that we are being critical (i.e. finding fault with a game), but rather that we are able to analyze games critically (as in, being able to analyze them carefully by considering all of their parts and how they fit together, and looking at both the good and the bad).

Vocabulary might not be as fascinating as that game you want to design with robot laser ninjas, but it is important, because it gives us the means to talk about games. Otherwise we’ll be stuck gesturing and grunting, and it becomes very hard to learn anything if we can’t communicate.

One of the most common ways to talk about games is to describe them in terms of other games. “It’s like Grand Theft Auto meets The Sims meets World of Warcraft.” But this has two limitations. First, if I haven’t played World of Warcraft, then I won’t know what you mean; it requires us to both have played the same games. Second, and more importantly, it does not cover the case of a game that is very different. How would you describe Katamari Damacy in terms of other games?

Another option, often chosen by those who write textbooks on game design, is to invent terminology as needed and then use it consistently within the text. I could do this, and we could at least communicate with each other about fundamental game design concepts. The problem here is what happens after this course is over; the jargon from this course would become useless when you were talking to anyone else. I cannot force or mandate that the game industry adopt my terminology.

One might wonder, if having the words to discuss games is such an important thing, why hasn’t it been done already? Why hasn’t the game industry settled on a list of terms? The answer is that it is doing so, but it is a slow process. We’ll see plenty of this emerging in the readings, and it is a theme we will return to many times during the first half of this course.

Games and Play

There are many kinds of play: tossing a ball around, playing make-believe, and of course games. So, you can think of games as one type of play.

Games are made of many parts, including the rules, story, physical components, and so on. Play is just one aspect of games. Therefore, you can also think of play as one part of games.

How can two things both be a subset the other? It seems like a paradox, and it’s something you are welcome to think about on your own. For our purposes, it doesn’t matter — the point here is that games and play are concepts that are related.

So, what is a game, anyway?

You might have noticed I never answered the earlier question of what a game is. This is because the concept is very difficult to define, at least in a way that doesn’t either leave things out that are obviously games (so the definition is too narrow), or accept things that are clearly not games (making the definition too broad)… or sometimes both.

Here are some definitions from various sources:

* A game has “ends and means”: an objective, an outcome, and a set of rules to get there. (David Parlett)

* A game is an activity involving player decisions, seeking objectives within a “limiting context” [i.e. rules]. (Clark C. Abt)

* A game has six properties: it is “free” (playing is optional and not obligatory), “separate” (fixed in space and time, in advance), has an uncertain outcome, is “unproductive” (in the sense of creating neither goods nor wealth — note that wagering transferswealth between players but does not create it), is governed by rules, and is “make believe” (accompanied by an awareness that the game is not Real Life, but is some kind of shared separate “reality”). (Roger Callois)

* A game is a “voluntary effort to overcome unnecessary obstacles.” This is a favorite among my classroom students. It sounds a bit different, but includes a lot of concepts of former definitions: it is voluntary, it has goals and rules. The bit about “unnecessary obstacles” implies an inefficiency caused by the rules on purpose — for example, if the object of Tic Tac Toe is to get three symbols across, down or diagonally, the easiest way to do that is to simply write three symbols in a row on your first turn while keeping the paper away from your opponent. But you don’t do that, because the rules get in the way… and it is from those rules that the play emerges. (Bernard Suits)

* Games have four properties. They are a “closed, formal system” (this is a fancy way of saying that they have rules; “formal” in this case means that it can be defined, not that it involves wearing a suit and tie); they involve interaction; they involve conflict; and they offer safety… at least compared to what they represent (for example, American Football is certainly not what one would call perfectly safe — injuries are common — but as a game it is an abstract representation of warfare, and it is certainly more safe than being a soldier in the middle of combat). (Chris Crawford)

* Games are a “form of art in which the participants, termed Players, make decisions in order to manage resources through game tokens in the pursuit of a goal.” This definition includes a number of concepts not seen in earlier definitions: games are art, they involve decisions and resource management, and they have “tokens” (objects within the game). There is also the familiar concept of goals. (Greg Costikyan)

* Games are a “system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome” (“quantifiable” here just means, for example, that there is a concept of “winning” and “losing”). This definition is from the book Rules of Playby Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. That book also lists the other definitions given above, and I thank the authors for putting them all in one place for easy reference.

By examining these definitions, we now have a starting point for discussing games. Some of the elements mentioned that seem to be common to many (if not all) games include:

* Games are an activity.

* Games have rules.

* Games have conflict.

* Games have goals.

* Games involve decision making.

* Games are artificial, they are safe, and they are outside ordinary life. This is sometimes referred to as the players stepping into the “Magic Circle” or sharing a “lusory attitude”.

* Games involve no material gain on the part of the players.

* Games are voluntary. If you are held at gunpoint and forced into an activity that would normally be considered a game, some would say that it is no longer a game for you. (Something to think about: if you accept this, then an activity that is voluntary for some players and compulsory for others may or may not be a game… depending on whose point of view you are looking at.)

* Games have an uncertain outcome.

* Games are a representation or simulation of something real, but they are themselves make believe.

* Games are inefficient. The rules impose obstacles that prevent the player from reaching their goal through the most efficient means.

* Games have systems. Usually, it is a closed system, meaning that resources and information do not flow between the game and the outside world.

* Games are a form of art.

Weaknesses of Definitions

Which of the earlier definitions is correct?

None of them are perfect. If you try to come up with your own definition, it will likely be imperfect as well. Here are a few common edge cases that commonly cause problems with definitions:

* Puzzles, such as crossword puzzles, Sudoku, Rubik’s Cube, or logic puzzles. Are these games? It depends on the definition. Salen & Zimmerman say they are a subset of games where there is a set of correct answers. Costikyan says they are not games, although they may be contained within a game.

* Role-playing games, such as Dungeons & Dragons. They have the word “game” right in the title, yet they are often not considered games (for example, because they often have no final outcome or resolution, no winning or losing).

* Choose-your-own-adventure books. These are not generally thought of as games; you say you are “reading” a book, not “playing” it. And yet, it fits most of the criteria for most definitions of a game. To make things even more confusing, if you take one of these books, add a tear-out “character sheet” with some numeric stats, include “skill checks” on some pages where you roll a die against a stat, and call it an “adventure module” instead of a “choose-your-own-adventure book,” we would now call it a game!

* Stories. Are games stories? On the one hand, most stories are linear, while games tend to be more dynamic. On the other hand, most games have some kind of story or narrative in them; we even have professional story writers that work on multi-million-dollar video game projects. And even beyond that, a player can tell a story about their game experience (“let me tell you about this Chess game I played last night, it was awesome”). For now, keep in mind that the concepts of story and game are related in many ways, and we’ll explore this more thoroughly later in the course.

Let’s Make a Game

You might be wondering how all of this is going to help you make games. It isn’t, directly… but we need to at least take some steps towards a shared vocabulary so that we can talk about games in a meaningful way.

Here’s a thing about games. I hear a lot from students that they’re afraid they won’t be able to make a game. They don’t have the creativity, or the skills, or whatever. This is nonsense, and it is time to get that out of our systems now.

If you have never made a game before, it is time to get over your fear. You are going to make a game now. Take out a pencil and paper (or load up a drawing program like Microsoft Paint). This will take all of 15 minutes and it will be fun and painless, I promise.

I mean it, get ready. Okay?

We are going to make what is referred to as a race-to-the-end board game. You have probably played a lot of these; the object is to get your token from one area of a game board to another. Common examples include Candyland, Chutes & Ladders, and Parcheesi. They are the easiest kind of game to design, and you’re going to make one now.

First, draw some kind of path. It can be straight or curved. All it takes is drawing a line. Now divide the path into spaces. You have now completed the first step out of four. See how easy this is?

Second, come up with a theme or objective. The players need to get from one end of the path to the other; why? You are either running towards something or running away from something. What are the players represented as in the game? What is their goal? In the design of many games, it is often helpful to start by asking what the objective is, and a lot of rules will fall into place just from that. You should be able to come up with something (even if it is extremely silly) in just a few minutes. You’re now half way done!

Third, you need a set of rules to allow the players to travel from space to space. How do you move? The simplest way, which you’re probably familiar with, is to roll a die on your turn and move that many spaces forward. You also need to decide exactly how the game ends: do you have to land on the final space by exact count, or does the game end as soon as a player reaches or passes it?

You now have something that has all the elements of a game, although it is missing one element common to many games: conflict. Games tend to be more interesting if you can affect your opponents, either by helping them or harming them. Think of ways to interact with your opponents. Does something happen when you land on the same space as them? Are there spaces you land on that let you do things to your opponents, such as move them forward or back? Can you move your opponents through other means on your turn (such as if you roll a certain result on the die)? Add at least one way to modify the standing of your opponents when it is your turn.

Congratulations! You have now made a game. It may not be a particularly good game (as that is something we will cover later in this course), but it is a functional game that can be played, and you made it in just a few minutes, with no tools other than a simple pencil and paper.

Credit for developing this exercise goes to my friend and co-author, Brenda Brathwaite, who noticed that there is this invisible barrier between a lot of people and game design, and created this as a way to get her students over their initial fear that they might not be able to design anything.

Lessons Learned

If you take away nothing else from this little activity, realize that you can have a playable game in minutes. It does not take programming skill. It does not require a great deal of creativity. It does not require lots of money, resources, or special materials. It does not take months or years of time. Making a good game may require some or all of these things, but the process of just starting out with a simple idea is something that can be done in a very short period of time with nothing more than a few slips of paper.

Remember this as we move forward in this course. When we talk about iteration and rapid prototyping, many people are afraid to commit to a design, to actually build their idea. They are afraid it will take too long, or that the idea will not turn out to be as good as it seems in their head. Part of the process involves killing weak ideas and making them stronger, by actually making and playing your game. The faster you can have something up and running, and the more times that you can play it, the better a game you can make. If it takes you more than a few minutes to make your first prototype of a new idea, it is taking too long.

Homeplay

Some classes assign “homework problems.” I’m not sure what is less fun: the concept of work at home, or having problems. So, I call everything a “homeplay” because I want these to be fun and interesting.

Before this Thursday, read the following:

* Challenges for Game Designers, Chapter 1 (Basics). This is just a short introduction to the text.

* I Have No Words and I Must Design, by Greg Costikyan. To me (and I’m sure others will disagree), this essay is the turning point when game design started to become its own field of study. Since it all started here, for me at least, I think it only fitting to introduce it at the start of this course. (There is a newer version here[PDF] if you are interested, but I prefer the original for its historical importance.)

* Understanding Games 1, Understanding Games 2, Understanding Games 3, Understanding Games 4. These are not readings, but playings. They are a series of short Flash games that attempt to explain some basic concepts of games in the form of a game. The name is a reference to Understanding Comics, a comic book that explains about comic books. Each one takes about five minutes. (Source:gamedesignconcepts)

上一篇:设计师分享设计优秀游戏的5大法则

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号