探索性格模型分类对游戏设计的指导作用

作者:Bart Stewart

[本文综合参考了多个游戏心理学系统,旨在制定一个统一的模型,以帮助游戏开发者针对特定的玩家类型设计游戏。]

过去十多年相继出现了不计其数的玩家心理模型。在早期的简单模型中, Bartle分类法被认为是最有参考价值、最具持久性的模型之一。我认为,这是因为Bartle分类法能够反映玩家的游戏性格(即游戏状态下所表现出来的个性)。换而言之,Bartle之所以长期被引以为参考,是因为它借鉴了其他有效的一般性格模型。

事实上,一些流传已久的游戏类型和游戏设计模型在概念上可谓“资源共享”。所以,我的第一个主张是,无论是Bartle分类法,或者Caillois、 Lazzaro、 Bateman提出的游戏类型模型、 还是Edwards、Hunicke/LeBlanc/Zubek等人提出的游戏设计模型,都是本文所谓的统一模型的变体。

(游戏邦注:作者在本文中引用的Richard Bartle、David Keirsey、Christopher Bateman等人的文献参考,是其本人的理解。因此,读者不必将其当成原作者的本意。)

Bartle分类法的四种玩家类型

最初的四种Bartle分类法(提出者在他的书《Designing Virtual Worlds》中已将其拓展成8种)的正式描述出现在游戏Multi-User Dungeon (MUD)的联合制作人Richard Bartle所写的文章《Hearts, Clubs, Diamonds, Spades: Players Who Suit MUDs》中。

提出这个分类法的基础是,观察和分析玩家在多人游戏模式下所表现出来的行为。根据Bartle分类法的描述,可以把玩家分成四种类型,即杀手、成就者、探索者和社交家:

杀手:干扰游戏世界的运作或其他玩家的游戏活动。

成就者:通过克服游戏世界的挑战,不断积累声望等。

探索者:探索控制和运作游戏世界的系统。

社交家:与其他玩家沟通交流游戏内容,从而形成社交关系。

这四种类型的玩家是根据“内容”和“控制”,这两种主要的游戏玩法喜好分化而来的。“内容”和“控制”具有两种相互排斥的形式——“内容”强调单纯而直接地对游戏世界中的物品施加行为,或与游戏系统的深入互动;“控制”着重于玩家通过两条途径,即其他玩家的动态行为或相对静止的游戏本身,来体验游戏。

杀手和成就者的兴趣主要是对物品或人物施加行为,他们把物品和人物当作外部目标。而探索者和社交家更倾向于与物品或其他玩家建立更深刻的互动关系,即更关注内在品质。

与此类似,杀手和社交家热衷于与游戏中的其他玩家之间的动态互动;而成就者和探索者的主要关注点是控制存在于游戏世界本身的、由开发者定义的游戏内容物。

Bartle分类法的理论基础是两组互补的玩家目标:动作或互动(内容)和玩家或游戏世界(控制)。Bartle据此画出了一个四分坐标图,每个象限对应一种玩家类型。玩家可以根据以上四种类型的描述和四分坐标图找到自己的对应类型。例如,偏好动作且更关注游戏世界的玩家在游戏时,更可能属于游戏中的成就者。

以下是Bartle 分类法的四分坐标图(游戏邦注:本图实际上是把原图顺时针旋转了90度,原图出自《Players Who Suit MUDs》,至于原因,请读者耐心往下读,自会明白)。

Keirsey性格模型的四种性格类型

上世纪70年代,心理学家David Keirsey把Myers-Briggs人格模型中描述的16种类型提炼成四种一般类型。在他的(合作者Marilyn Bates)《Please Understand Me》一书中,Keirsey描述了这4种“性格”,同时给出名称:

技师(感觉+理解):现实主义、策略、操作(对像为人或物)、实用主义、冲动、行动导向、感觉导向

守护者(感觉+判断):务实、逻辑、等级、组织、注重细节、占有、过程导向、安全导向

理性者(直觉+思考):创新、战略、逻辑、科学/技术、前景导向、结果导向、知识导向

理想主义者(直觉+感情):想象、交际、情绪、关系导向、引人注目、“以人为本”、身份导向

在这本书的第二版本《Please Understand Me II》中,作者和Richard Bartle一样,把他的4种性格类型划分为四个象限,以体现四者在内部结构上的联系。然而,在他提出这个模型时,我已经得出另一个稍微不同的分类版本。

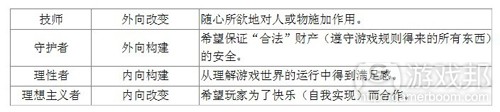

我认为最基本的人类行为分类是,内在(偏向可能性和抽象性) vs. 外在(偏向具体性和现实性)和改变(自由和机遇) vs. 构建(规则或组织)。如此一来,四种性格就各自综合了外在/内在和改变/构建这两对元素:

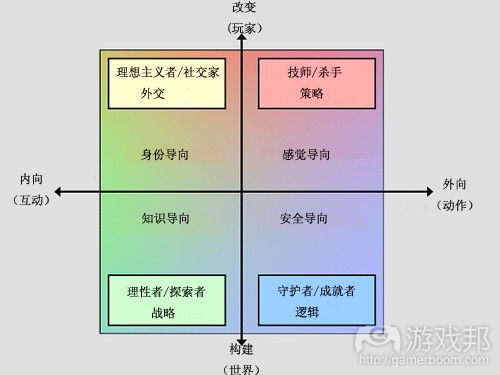

保留Richard Bartle的四种类型,再替换上我个人主张的坐标轴,我们就得到了新的Keirsey性格模型。如下图所示:

Keirsey和Bartle

本文我主要探讨的是Keirsey 和Bartle主张的分类模型。首先,我们谈谈David Keirsey描述的四种性格类型——技师、守护者、理性者和理想主义者——分别对应 Richard Bartle描述的四种玩家类型:

Bartle认为对游戏玩家施加作用的倾向,映射到性格理论上,就是偏向于内向或外向改变。以此类推,在Bartle分类法中,关注游戏玩法的倾向,在性格理论中的描述是,关注动态的玩家或静止的游戏世界的倾向。我个人版本的Keirsey性格模型认为,玩家通常倾向于改变或构建。我认为因为Bartle分类法和Keirsey性格模型之间存在两种基本的价值动机的类比,所以由这些动机产生的类型和性格之间也存在类比。

下图是Keirsey性格模型和Bartle分类法的结合版:

以下是关于各个组合的简要描述,表现了Keirsey和Bartle如何根据相同的基本动机总结出各种性格/玩家类型。

理想主义者/社交家:Bartle如此描述社交家:“……对人感兴趣,他们认为游戏玩家之间的关系很重要……玩家的成长是个体性的,随着不断成熟,唯一基本上有意义事就是……渐渐知道他人、理解他们、形成美妙持久的关系。”

以上描述与Keirseian对理想主义者的描述颇有联系:理想主义者充分意识到他人是自我发现(内在改变)的生命之旅中的一部分。一定程度上,想象力丰富的理想主义者总是在进行角色扮演——他们不断地创造自己的(或他人的)意象,为了达到自己渴望的感觉,他们觉得应该通过自己的行动来模拟。

守护者/成就者:对于守护者而言,游戏世界是一个危机四伏的地方,所以有必要通过积累物质财富来保护好自己……只是为了以防万一。因此,守护者注重收集金钱、争夺稀有资源、购买和储备上好货物、形成稳定而持久的团体关系、利用财富(外向构建)锁定自己与游戏世界的联系,从而保持自己在游戏世界的地位。

Bartle对成就者的描述是这样的:“成就者把积分和升级当作主要目标,……成就者为自己在等级制度森严的游戏世界占据正统地位而感到自豪,为自己能在如此之短的时间内达到这样的地位而骄傲。”升级、领导和积累大量掉落物品等行为都受到安全导向型动机的驱使,而其他动机,如强大的觉察力、对自我成长的理解则没有这样的激励作用。

这就解释了为什么守护者/成就者热衷于“重复刷任务”的行为,而其他玩家丝毫看不出这种行为的乐趣所在。对守护者/成就者而言,所谓一分耕耘一分收获,奖励应该与投入成正比。当某款游戏围绕简单明确的、能够积累地位标识的任务设计时,它必定能吸引安全导向型玩家的目光。

理性者/探索者:理性者的处世行为一成不变——探索原始数据(内向构建)背后的组织性结构能给他们带来快乐。这些原始数据可以是空间(地理)或时间(形态)特征,也可以是因果特征(要求)或关系特征(联系)。基本上,理性者的快感来自从战略的高度上理解作为整体的游戏系统。

Bartle对探索者的描述如下:“真正的乐趣来自探索和收集最齐全的游戏地图。”在核心动机——找感觉、找安全、找知识和找身份中,作为“发现”的探索最接近于理性者的知识引导倾向。对理性者/探索者而言,一旦数据背后的规则水落石出了,这就足够了——理解本身就是一种奖励。这些玩家可以从知识分享中得到乐趣,但他们向别人传授知识并不需要或期望得到额外奖励。

技师/杀手:最后,我们再说说杀手(或者我更偏向于称他们为“操纵者”)。就游戏玩法而言,这些人非常难理解,因为大多数虚拟世界的编码规则已经把他们的操作风格作为“不安定因素”(即使其他玩家焦虑不安)给边缘化了,且试图扑灭杀手风气。正如Bartle所言:“杀手的快感是建立在把自己的行为强加给别人的基础上。”他还指出,杀手“希望只表现他们凌驾于他人之上的一面。”

这种渴望掌控一切的力量与Keirseian 对技师的描述遥相呼应。技师(如他们的性格标签所示)喜好技术型操作。技师/杀手是工具使用者、亢奋狂人、天生的政治家、战斗专家、冒险的赌徒和卓越的谈判者。无论是什么战略情形,找到并表现出优势几乎是他们的本能。为了保持最大限度的个人自由(外向改变),他们表现出统治自己世界的要求。

在2011年的GDC的游戏开发者演说上,Ryan Creighton展示了他的硬币收集游戏,其中有个“社交工程”部分(“social engineering”),我们可以从中找到以上描述的力证。为了获得游戏的胜利,守护者/成就者会在遵守游戏规则的前提下,满屋子地找别人要硬币;理性者/探索者会淡定地坐看硬币的交易,试图发现游戏的本质;技师/杀手会不断地研究如何缩短游戏时间,并且,作为天生的谈判专家,他们很轻易地能说服别人把一袋子金币拱手相让。看吧,事情就是这样。

如果参与者需要听什么人的慷慨陈辞,那个人肯定是操作者。他们只是等待着时机出现,然后在精心设计的社交游戏规则中引起一点小混乱。(详见Ryan的第一手描述,个人认为这是个研究技师/杀手的经典视角。)

最后注意一下Keirsey/Bartle的结合版模型:Keirsey性格模型和Bartle分类法在某些方面的视角可能并不一致。这是因为Bartle分类法来源于多玩家环境,倾向于外向型玩家,而性格模型则兼顾了外向型和内向型两种玩家。

比如,在Bartle分类法中,称注重社交互动的人为“社交家”是合情合理的,但对于偏好单人游戏的内向空想家,似乎担不起”社交家“之名。这些不太讲社交的社交家更喜欢个人化的娱乐方式或抽象游戏,在这点上有些贴近理性者/探索者,因此很难将他们各自区别出来。进一步研究通常需要考虑他们玩游戏的主要原因是找乐子(理想主义者倾向)还是训练思维技巧(理性者倾向)。

Chris Bateman的DGD1模型

即使考虑到了内向性和外向性,并非所有玩家都能在四种基本性格类型中把自己对号入座。 Bartle分类法和Keirsey性格模型都没有好好解决这个现实问题。有些人认为自己既像内向型玩家,但也有外向型的表现,既重视改变也不忽视构建。

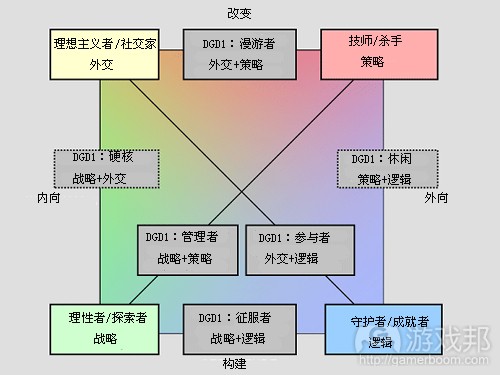

由Christopher Bateman编写的书《21st-Century Game Design》,探究了游戏玩法设计的“集群游戏设计”模型(”demographic game design” model (DGD1)),我认为这个模型有利地配合了Keirsey/Bartle模型。 Bateman 提出的模型虽然没有匹配各个性格类型,但形成了次级游戏类型,从而填补了主要游戏类型之间的空白地带。

Bateman 所定义的四种游戏类型元素和硬核/休闲模式一样,不直接映射 Keirsey/Bartle模型,但对应了四种 Keirsey/Bartle类型之间的空白段。下图反映了这种叠加关系(返回看前面几张图,这下明白为什么我说是顺时针旋转90度了吧?):

Bartle分类法存在“绝对化玩家类型”的缺陷,DGD1的价值(除了实用性和本身作为性格模型的价值)就在于填补这个不足。有些玩家知道自己的类型介于探索者和成就者之间,或混合了策略(理性者)和逻辑(守护者)两种表现,往往“不适合”用Bartle分类法归类,但现在他们可以借助DGD1模型,知道自己倾向于征服者类型。DGD1模型并没有摒弃Bartle分类法的价值,相反,DGD1模型深化、升华了这个分类法,从而引出Keirsey/Bartle/Bateman模型(结构如图4所示)。

注:《21st-Century Game Design》出版后,DGD2模型的问卷随之出现在iHobo网站上。DGD2模型由基于Myers-Briggs的DGG1模型衍生出来,更加明确地围绕Keirsey性格模型构建。DGD2没有破坏或更改DGD1所提出的游戏类型模型,而是采纳了Keirsey性格理论的某些概念,在Keirsey性格模型(和Bartle分类法)的DGD1模型中突出了征服者、管理者、漫游者和参与者类型。(即后来的BrainHex六分模型。)

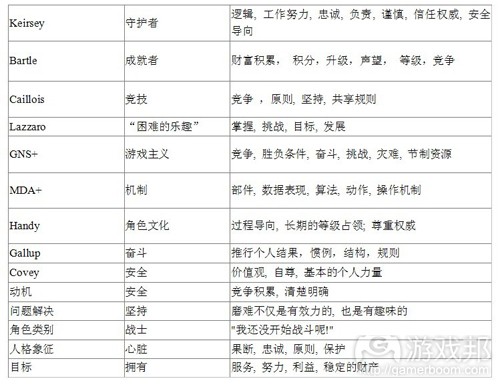

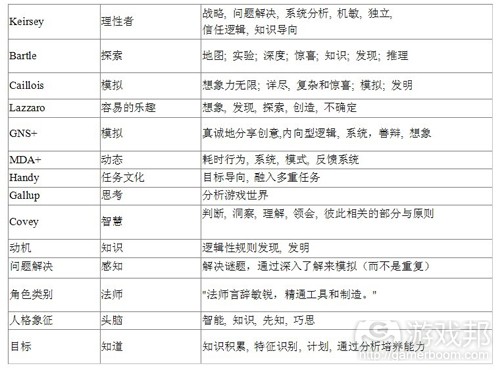

统一模型

在我研究关于玩家类型和游戏玩法模型的文献时,我很惊讶地发现,许多其他模型也各自提出了三分或四分法。更引人注目的是,不同作者对各自的分类法的说辞非常贴近Keirsey/Bartle模型描述的核心游戏类型。

因此,我的第二个主张是,不仅Bartle分类法是Keirsey性格模型的子类,还有无数个其他知名的游戏和游戏设计模型也是四种基本性格类型的变体。

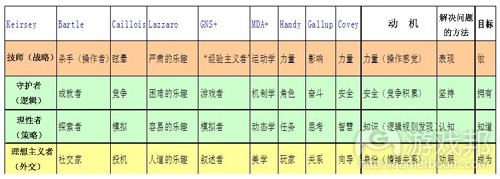

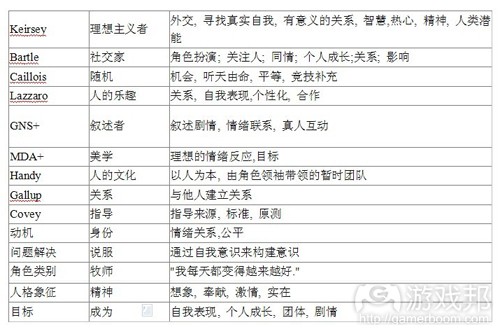

当然,还存在其他性格和游戏模型并不是四种基本风格的变体,这也是我们必须承认的事实。我明白这个道理,所以我没打算把我见到的所有性格类型都凑成一个。作为一名资深系统设计师,我充分意识到“把各种现象都当成既定理论的实例”是很危险的——我已经尽力避免这种错误,我所做的不过是把各种分类模型的元素对应地列成一个表:

上表使用提出者挑选出的词来表示各种游戏类型或人格模型的基本概念。该表旨在一目了然地展现游戏类型和游戏设计层次模型之间的关联。另外,本表也参考了其他活动团体(办公室等工作场所)成员的性格模型,我还在后面列了三个独立项(动机、问题解决和目标),作为对各个类型的意义解读。

当Caillois和Lazzaro遇到Keirsey和Bartle

统一模型的第一部分把Keirsey的人类性格一般理论与Richard Bartle、Roger Caillois和 Nicole Lazzaro描述的四种基本游戏类型联系起来。

注:尽管Roger Caillois表示他不认为他所描述的四种类型是完整的分类,我个人倒是认为,他的理论比他所想的更好。他提出的六个概念完整地填补了其他人得出的四种核心类型之间的“空隙”。因此,我主张把他提出的模式归入标准模型中,当然,允许读者持有不同的意见。

Caillois描述的“眩晕”(ilinx)的乐趣、亢奋,对应感觉导向型动机,即Bartle和Keirsey各自对杀手和技师的形容。

Lazzaro的“严肃的”或“深沉的”乐趣(游戏邦注:她在关于游戏条件下的情绪反映的群集分析文中,定义四种核心情绪类型,这是其中之一)也指向感觉导向,特别是,寻找来自积极游戏的内在奖励——兴奋和轻松的感觉。再者,这种定位非常接近于技师/杀手在熟练操纵人物或物品(外向改变)时产生的感觉。

无论是Caillois的“眩晕”说还是Lazzaro的“困难的乐趣”论,其在概念上都接近Bartle(成就者)和Keirsey(守护者)所主张的安全导向型动机。“眩晕”和“困难的乐趣”都是关于在遵守游戏竞争规则的前提下得到实在的、外在的奖励——这是成就者/守护者的确凿特征,他们坚信,游戏世界必须有一套完备的规则、且在遵守这种规则的条件下,玩家的付出与收获必须成正比。

Caillois显然把模仿与“模拟”,或者对二次元现实的积极建设相关联。这正是富有创造力的理性者/探索者的所作所为。对于理性者,探索或建立新世界的乐趣反映了他们作为探索者的独一无二的个性,从而使他们能够理解新世界的内部构建。热衷于模仿的理性者/探索者就这样与Lazzaro的“容易的乐趣”搭上了关系。 “容易的乐趣”,描述的是沉浸于游戏体验的玩家偏好。

Caillois描述的第四种游戏模式,即机会,因为是建立在随机性和机遇性的基础之上,所以根据随机的死亡名单或卡片变化,决定结果,就能把公平性加储于所有玩家。对理想主义者/社交家而言,这种方式无可厚菲,因为这与游戏的规则几乎没有关系,运气不仅是可以接受的,甚至可以说是必须公平地散布在结果中。规则是人定的,为的是保证玩家之间(与人类或NPC)的互动。这几乎与Lazzaro构想的“人的乐趣”不约而同,在游戏世界中,这种随机乐趣不仅是可使用的工具,也是要克服的挑战、要理解的系统,还是玩家彼此享受有意义的关系的社交背景。

GNS+和MDA+

除了这些游戏类型模型,还有两种重要的游戏设计模型,在定义上,与 Keirsey的性格模型有关。它们就是:游戏者/叙述者/模拟者(GNS)游戏设计模型(由Ron Edwards最先提出,简称为GNS+模型,但后来被弃置不用了) 和机制/动态/美学(MDA)框架(由Hunicke、LeBlanc和Zubek阐述,简称为MDA+模型)。

三分法的GNS+模型与Keirsey/Bartle的三种分类形成紧密的对应。游戏者设计的风格,注重游戏的操作机制或规则,显然是对应了以规则导向、竞争、难度的乐趣引导为关键词的守护者/成就者。与此类似,理性者/探索者最可能被模拟者的设计风格所吸引,即为建设和投入到复杂而逻辑上一致的游戏世界而到快乐。而“以人为本”、“人的乐趣”的剧情叙述则受到理想主义者/社交家的青睐,而这也是叙述者使游戏有趣的主要手段。

以上解释并没有提及原始的感觉性。第四种设计风格(即我所谓的经验主义者)强调游戏产生强烈的体验的功能——这是我对感觉导向型的技师/杀手的描述。如果经验主义者的有效性受到与游戏者、叙述者和模拟者相同的认可,那么,我们就得到了一个与Keirsey/Bartle模型及其他相关游戏模型完全平齐的GNS+模型。

在我看来,把这种类型补充到GNS模型中未尝不可。在Robin Laws提出的游戏类型模型中,经验主义者的倾向与“亢奋”玩家类型非常相似。另外,喜欢享受激烈的游戏体验正好类比 Caillois所描述的“眩晕”乐趣。

对于MDA游戏设计模型,我打算“故计重施”。与GNS+模型的描述似类,MDA模型只缺少一个着重于直接的动作欣赏的设计类型,也就是游戏设计师想从玩家身上引出的精神层面上的感觉。我主张把“运动”作为MDA+模型中的第四种风格的名称,运动再次对准了Caillois的“眩晕”偏好,即寻找动作导向型游戏中的乐趣(有趣的是,最初的GNS和MDA模型都缺少概念来描述操作如何产生紧张的感觉)。

和最初的GNS模型一样,MDA模型的三个类型对应了统一模型所描述的游戏类型和性格类型。作为约束玩家行为的规则,机制是守护者/成就者的首要选择,他们自然而然地欢迎游戏者的设计方法。 “但你在游戏里到底玩什么?”的最实际的回答就是机制。动态是模拟型理性者/探索者最主要的兴趣所在,他们不由自主地把注意力放在游戏的功能性行为上,因为这能给他们带来独特的二次元生活体验。理想主义者/社交家总是对他人抱着理想的观念,并以此作为游戏的态度,他们能够以最快的速度觉察到某款游戏是否满足美学要求——即这款游戏好不好。

解释完了理论,接下来我们准备研究统一模型的用途。

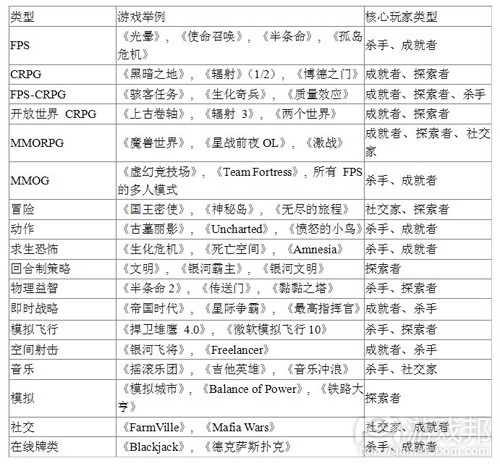

以统一模型解读当前游戏

有效的模型应该能够解释为什么某种游戏能满足某类玩家的喜好要求。以热门的FPS游戏,如《使命召唤》或《战场》系列为例,这些游戏强调高仿真的面面、在高压情形下做出快速的战略行动、真实的敏捷操作、快感时刻、清楚标记的内部线路、令人眩目的部件组合、可收集的成就/战利品、(多人模式下)激烈的竞争、基于角色的合作、团体领导的地位标记。所有的这些特征都与外向性(大多是直接的真实体验)有关,而与抽象的内向品质(如思考或感觉)关系不大。

在FPS中,高速、激亢的战略行动的直接受众是外向型的技师/杀手。外向型的守护者/成就者的喜好是处理写得一清二楚的操作规则、收集游戏内物品和成就(这是他们采取行动的目的)。一定程度上,如果一款游戏高度强调以上两方面元素,那么这款游戏既能受到技师/杀手的青睐,也能博得守护者/成就者的好感。这种混搭组合放在Chris Bateman的DGD1模型中的休闲游戏模式中,可能有些奇怪——纯FPS的游戏通常是非常紧张刺激——但它符合Chris Bateman描述的“休闲”游戏的概念,根据这种概念,玩家在游戏中没有投入多少情绪,所以想玩就玩,想退就退,游戏主题很实在,也很容易理解,且针对的是大众市场。

站在实时动作/竞技游戏类型对立面的是冒险游戏,如《神秘岛》、《无尽的旅程》和创意游戏,如《Minecraft》或回合制策略游戏《文明》。这些游戏的内在特征既强调剧情,又注重与情绪和思考有关的元素,正是强调动作和竞争积累的外向型FPS的实例。我们有理由认为,大多数带有强烈的FPS倾向的游戏玩家不喜欢冒险游戏,而大多数自认为是冒险游戏玩家的人并不待见典型的FPS。这正是标准模型,结合互相对立的硬核(剧情/益智)和休闲(动作/积宝)倾向,根据游戏类型分析做出来的预测。

如果统一模型有效,那么它应该也能够解释“出乎意料”成功的游戏(如《Minecraft》)的吸引力所在。在我写这篇文章时,《Minecraft》仍在测试阶段,现在它已经为开发商积累了数千万美元的收益。该作的着力点有二:创意探索和刺激求生。当玩家探索洞穴或搭建筑物(都是探索导向型的活动)时,玩家的角色可能会突然被猛兽攻击。杀手最看好这或战或逃的刺激反应,另外,搞破坏、从高处跳下、(被推)落入致命的岩浆中等实实在在的感觉也颇讨杀手的欢心。

理性者/探索者和技师/杀手的结合相当于Chris Bateman的DGD1模型所描述的强调策略/战略的“管理者”游戏类型。Chris Bateman将“管理者”描述为,可以在自己确实喜欢的游戏上奋战数小时的“复杂引导型玩家”,他们的类型“与精通和系统有关”。这几乎解释了《Minecraft》为什么能够对那些喜欢按自己的设计重置游戏的玩家群体产生强大的吸引力。

(有趣的是,《Minecraft》的主设计师在游戏中增加了成就系统,将以“冒险升级”为名发布。这些新的功能特征可能受到守护者/成就者的欢迎,因为当前的守护者/成就者从他们的角度出发,抱怨《Minecraft》高度非指向性的游戏玩法很无聊很难讨喜。吸引成就者的新功能特征发布后,《Minecraft》能否保持探索型杀手的忠实,是个值得探讨的问题。)

在下表中,我列出了各种游戏在统一模型中的对应类别:

统一模型的另一个潜力是,通过玩家声称的在玩游戏来定位玩家自然游戏类型。这一定程度上受到个体玩家对“游戏玩家”文化的投入程度的影响。玩家越是积极地把玩新游戏当成生活习惯,统一模型就越能准确地推断他们的一般性格类型。

另一方面,如果一个人只是玩一点轻型的或大众化的游戏(如《大富翁》),要判定他的性格类型,统一模型的预测性的精度可能极低。在这种情况下,没有任何模型能够起作用,因为做推断的信息实在不足。 即使是强调多人游戏的Bartle分类法也很难对那些偏爱单人游戏的玩家作出判断。

此外,个人的游戏选择有可能不能完美地对应到四种主要类型中。此时,可以考虑他们可能是DGD1模型所描述的四种类型之一。在DGD1模型中,各个类型都是Keirsey/Bartle模型描述的两种主要类别的组合。

通常情况下,玩家玩的游戏越多,他们对游戏玩家文化的投入程度就越高——统一模型对他们的性格类型的定位就越精确。反之也成立:玩家玩的游戏越少,统一模型的推断精度越差。这不是统一模型的缺陷,而只是缺少足够的归类信息。

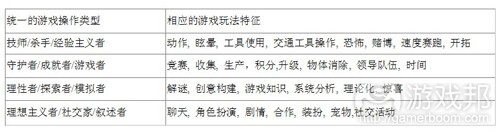

统一模型促进新游戏设计

统一模型本身并不涉及游戏玩法功能特征。但它有可能把玩法功能特征与特定的游戏类型倾向联结起来——不同的活动显然满足不同的需要。这样,设计师就可以根据各种功能特征的适应性来制定有针对性的设计目标。

下表反映了游戏玩法功能和游戏类型的对应:

假如,你将设计一款令人兴奋的、“有大量奖励”的游戏。根据上表,你可以看到“令人兴奋的”对应的应该是技师/杀手风格,而“奖励”显然偏向守护者/成就者。那么你所需要的就是,一种综合了两种元素(如果可能)的游戏玩法,但至少确保涉及其中之一。

所以,理想的游戏概念可能是一些街机风格的赛车游戏。这类游戏需要高度物理性环境,使玩家可以直接精确地操作赛车(但为了顺利得到奖励,玩家必须技艺精湛)。要让游戏的核心机制既强调紧张的操作动作,又注重简单的满足感、清楚的奖励收集目标、就必须保证所有针对这两种游戏类型的对象参与其中。尽管,高度调强物理性和物品丰富的动作、同时取悦技师/杀手和守护者/成就者的游戏,非常少见。根据上例,统一模型的作用就是促进新游戏的设计,因为它强大的测试的建设性作用可能会启发开发者考虑到不太常见的游戏业型组合。

那么,同时迎合理想主义者/社交家的内向改变目标和技师/杀手的外向改变渴望的游戏是怎么样的呢?(对应DGD1模型的“漫游者”类型)这样的游戏,如果不掺杂理性者/探索者和守护者/成就者的模拟者或游戏者的构建倾向,可能会变成很混乱的、高度社交化的、狂事突发的环境。(事实上,这听起来非常像《第二人生》,对吧?这样的东西能像单人游戏那样运作吗? Facebook 游戏又怎么样呢?)

融合守护者/成就者和理想主义者/社交家这两个对立的倾向为一体的游戏也不太常见(对应的类型应该是DGD1模型中的“参与者”游戏风格)。为了完整地构成这种独特的品质,这类游戏必须强调基于规则而产生社交关系和活动的游戏功能特征。如此,成就者可以欣赏社交的稳定性和“社交升级”,同时社交家也可以欣赏到创造关于玩家的强大工具。(尽管这类游戏大概已经存在了——《模拟人生》不正是综合了这两种游戏风格吗?其他参与者风格的游戏不正是《模拟人生》的翻版吗?)

结论

虽然没有什么人类行为模型堪称完美,但现实问题只是,一个既定的模型是否能够帮助游戏设计师有效地预测玩家的需求、解释需求的原因、启发满足需求的办法。就这点看来,我认为我所主张的统一模型再加DGD1模型,不失为一套充分地解释和预测玩家偏好的整体理论。

有些人当然会反对统一模型的某个方面,或甚至否认所有“把人框架化”的性格模型的整个概念。 我不指望这些人承认该模型的巨大启发价值。毫无疑问,许多人也各自观察得出不少独特的关联组合,如Ethan Kennerly探索Bartle分类学和David Keirsey性格模型之间的相似性。Christopher Bateman也在他的DGD分类法中详述许多游戏类型模型的组合。

我认为统一模型给我们提供的是一种深刻的研究视角,即不止是一两种知名的游戏操作或游戏设计理论互相或与一般性格模型之间存在紧密的关系,无数种理论都是相辅相成的。

包括统一模型,各种理论的提出者都达成共识:玩家希望根据一般性格类型来表达自己的游戏类型。我指出多种模型共享的特征,旨在为正在思考玩家动机以设计出更优秀游戏的设计师提供一个理论框架。

如果有其他模型能够更好地展示解释和预测的力量,那么,我会很乐意地抛开现在这个模型,热心的接纳新模型。重要的不是我个人的“正确”,而是有志于创造好游戏的人可以拥有一种实用的概念工具。

如果有人可以拿出更易解读和预测游戏类型的模型,玩家和游戏开发者、发行商都将从中受益。

我希望设计师在谈论或设计游戏时,这个统一模型可以对他们有所启发。

附录

以下表格表现了各个类型的信息。这不仅反映了各个分类法之间的概念联系,还可以充当特定游戏玩法要求的设计指导。

注:“Keirsey”到“Covey”这几行文本的第三列是直接摘自各个游戏类型或性格模型的主张者的文献或展示。Caillois部分的文字出自Meyer Barash对原文《Les Jeux et Les Hommes》 的英译版。GNS+中的“经验主义”和MDA+中的“动力学”(Kinetics)完全是我个人的说法,因为三个模型中都不存在这些概念。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Personality And Play Styles: A Unified Model

by Bart Stewart

[In this comprehensive analysis, multiple psychological systems of gameplay are surveyed, to try and arrive at a unified model in which player behavior can be understood and, crucially for game developers, catered to.]

Numerous models of gamer psychology have been proposed and debated over the past couple of decades. One of the earliest and simplest has proven to be one of the most referenced and most enduring: the Bartle Types. I believe this is because the Bartle Types are a functional model of human personality in a game playing context. In other words, the Bartle typology works because it’s a subset of a more general personality model that works.

In fact, several of the best-known play style and game design models share many conceptual elements. So I’m also proposing here that the Bartle typology, the play style models of Caillois, Lazzaro, and Bateman, and the game design models of Edwards and Hunicke/LeBlanc/Zubek are all variations on a single Unified Model of play styles.

(Please note that any and all references I make in this article to the works of Richard Bartle, David Keirsey, Christopher Bateman and others that aren’t clearly sourced as quotations are my own interpretations. As such, they should not be considered official descriptions of these authors’ ideas.)

The Four Bartle Types

The official description of the original four Bartle Types (which have been expanded to eight types in Richard Bartle’s book Designing Virtual Worlds) is preserved in the paper “Hearts, Clubs, Diamonds, Spades: Players Who Suit MUDs” by Multi-User Dungeon (MUD) co-creator Richard Bartle.

This model, which was based on observing and analyzing the behaviors people playing together in a multi-user game, holds that there are four different kinds of play style interests, each of which is given a descriptive name: Killers, Achievers, Explorers, and Socializers.

Killers: interfere with the functioning of the game world or the play experience of other players

Achievers: accumulate status tokens by beating the rules-based challenges of the game world

Explorers: discover the systems governing the operation of the game world

Socializers: form relationships with other players by telling stories within the game world

These four styles emerged from the combination of two primary gameplay interests, which I’ve called Content and Control, each of which has two mutually exclusive forms. Content is defined to mean either acting simply and directly on objects in the game world, or interacting more deeply with world-systems. Control refers to how players want to experience the game world — either through the dynamic behaviors of other players, or with the relatively static world of the game itself.

Killers and Achievers both turned out to be mostly interested in acting on things or people, treating things and people as external objects. At the same time, Explorers and Socializers both seemed to prefer a deeper level of interacting with things or other people, focusing on internal qualities.

Similarly, Killers and Socializers both seemed eager to have the opportunity to control how they are able to play dynamically with others in the game world, while Achievers and Explorers seemed most interested in controlling their relationships with the developer-defined objects in and properties of the game world itself.

The bases of the Bartle Types are thus two pairs of complementary player goals: Acting or Interacting (content), and Players or World (control). Bartle represented these interests as two lines at right angles to each other to create a grid with four quadrants, each quadrant corresponding to one of the four observed play style preferences. By determining his preference for Acting vs. Interacting and for Players vs. World, then looking up the play style in the quadrant corresponding to that combination, any gamer could easily identify his naturally preferred play style. A gamer who prefers acting over interacting and is focused more on the world of the game than other players, for example, would most likely demonstrate Achiever behaviors when playing a game.

Here’s a diagram showing how the four Bartle Types emerge from the conjunction of the two major gamer concerns with content and control. (Note: This table is rotated 90 degrees clockwise from the version presented in “Players Who Suit MUDs” for reasons that will become apparent later in this article.)

The Bartle Types

The Four Keirsey Temperaments

In the 1970s, psychologist David Keirsey identified four general patterns from the sixteen types of the Myers-Briggs personality model. In his book (co-written with Marilyn Bates) Please Understand Me, Keirsey described these four “temperaments,” giving them descriptive names much as Richard Bartle named his player types:

In the second edition of Keirsey’s book, Please Understand Me II, Keirsey grouped his four temperaments as four quadrants across two axes to show how they were related according to an internal structure, very much as Richard Bartle had. However, by the time he proposed his grouping model in the second edition of his book, I had already worked out a somewhat different arrangement.

Rather than the two dimensions that Keirsey used in his model, I believe the two most fundamentally distinctive dimensions of human behavior are Internals (a preference for seeing possibilities and the abstract) vs. Externals (seeing the concrete and realistic), and Change (which can be thought of as freedom or opportunity) vs. Structure (which can be understood as rules or organization). Each of the four temperaments is thus a combination of External/Internal and Change/Structure:

Here’s how these four styles are represented (using my two axes, not Keirsey’s) with the same kind of four-quadrant format that Richard Bartle used for the four Bartle Types:

The Keirsey Temperaments (Stewart Format)

Keirsey and Bartle

The first of the two major assertions I make in this article is that the four temperaments described by David Keirsey — Artisan, Guardian, Rational, and Idealist — are supersets of the original four player types — Killer, Achiever, Explorer, and Socializer, respectively — as described by Richard Bartle.

Where Bartle sees a preference for interacting with or acting on players in a game context, temperament theory sees a more general preference for internal or external change. And where Bartle focuses in a gameplay context on a preference for dynamic players or the static world, my version of Keirsey’s four-quadrant model has people generally preferring change or structure. I believe that because the basic two-valued motivations are analogous between the Bartle Types and the Keirsey temperaments, the types and temperaments that are generated by these motivations are also analogous.

The following diagram shows the alignment between the four Keirsey temperaments and the four Bartle Types:

Unified Model, Keirsey-Bartle Diagram

Here are some brief descriptions of each combination, showing how Keirsey and Bartle ascribe the same basic motivations to each temperament/type.

Idealist/Socializer: Socializers are described by Bartle as “… interested in people, and what they have to say. … Inter-player relationships are important … seeing [people] grow as individuals, maturing over time. … The only ultimately fulfilling thing is … getting to know people, to understand them, and to form beautiful, lasting relationships.”

This is closely related to the Keirseian description of Idealists, who are very aware of other people as part of their lifelong journey of self-discovery (Internal Change). In a way, the highly imaginative Idealists are always roleplaying; they are constantly creating images of themselves (or others) that they feel they should model through their own actions in order to produce the emotions in themselves that they want to feel.

Guardian/Achiever: For the Guardian, the world is an insecure place, so it’s necessary to protect oneself by accumulating material possessions… just in case. Thus,

Guardians focus on earning money, on competing with others for resources perceived as scarce, on buying nice things and maintaining them, on forming stable and hierarchical group relationships, and generally on working hard to make their place in the world secure by locking down their connections to the world as possessions (External Structure).

Compare that to Bartle’s description of Achievers: “Achievers regard points-gathering and rising in levels as their main goal” and “Achievers are proud of their formal status in the game’s built-in level hierarchy, and of how short a time they took to reach it.” Leveling up, leaderboards, and the accumulation of vast quantities of looted items are all behaviors that are driven more by a security-seeking motivation than by other motivations such as powerful sensations, understanding or self-growth.

This explains why the Guardian/Achiever is willing to persist in long stretches of “grind” that other kinds of gamers don’t perceive as fun at all. To this gamer, rewards should be proportional to the amount of effort invested. When a game is designed around simple, well-defined tasks that enable the competitive accumulation of status tokens, that game is virtually guaranteed to attract security-seeking Guardian/Achievers.

Rational/Explorer: Rationals play in the same way that they do everything else — they find pleasure in discovering the organized structural patterns behind raw data (Internal Structure). These can be patterns in space (as in geography) or patterns in time (as in morphology). Or they can be cause-and-effect patterns (entailment) or relationship patterns (connections). Ultimately, it’s all about achieving a strategic understanding of the system as a whole thing.

As Bartle describes Explorers: “The real fun comes only from discovery, and making the most complete set of maps in existence.” Of the core motivations — sensation-seeking, security-seeking, knowledge-seeking, and identity-seeking — exploration as “discovery” is most closely aligned with the Rational’s knowledge-seeking preference. For the Rational/Explorer, once the principle behind the data is revealed, that’s enough — understanding is its own reward. These gamers can enjoy imparting knowledge to others, but no extrinsic reward for doing so is needed or expected.

Artisan/Killer: Finally, there are the Killers (or, as I prefer to call them, Manipulators). These can be difficult to understand in a gameplay context because most virtual worlds have encoded rules that marginalize their play style as “griefing” (i.e., upsetting other players) and try to prevent it. As Bartle puts it, “Killers get their kicks from imposing themselves on others.” He also points out that Killers “wish only to demonstrate their superiority over fellow humans.”

This desire for power over everything in their world is most closely echoed in the Keirseian description of Artisans, who (as their temperament name suggests) delight in the skillfully artistic manipulation of their environment. The Artisan/Killers are the tool-users, the adrenaline junkies, the natural politicians, the combat

pilots, the high-stakes gamblers, and the negotiators par excellence. They instinctively find and exploit advantages in any tactical situation, and they express this

need for dominance of their world in order to retain the greatest amount of personal freedom possible (External Change).

I believe a very good example of this can be found in Ryan Creighton’s “social engineering” of the coin-collecting game at the Social Game Developers Rant of the 2011 Game Developers Conference. A Guardian/Achiever would have played by the rules and raced around the room begging others for their coins to try to win the game; an Idealist/Socializer would have asked for coins as a way to meet new people or help others win; and a Rational/Explorer would have sat quietly watching the flow of coin exchanges to try to understand the nature of the game. But an Artisan/Killer would instantly see how to short-circuit the designed system, and, as a born negotiator, would find it easy to persuade the person holding one of the bags of coins to hand the whole thing over… which is exactly what happened.

If the attendees needed to hear a rant from anyone, it would be the Manipulator who is out there, just waiting to exploit any opportunity to bring a little chaos to the carefully designed order of a social game. (See Ryan’s description of the event for a wonderful first-hand account of gameplay from what appears to me to be a classic Artisan/Killer perspective.)

A final note on the Keirsey/Bartle linkage: the Keirsey temperaments and Bartle Types may appear not to line up directly where attitudes toward other people are concerned. This is because the Bartle Types were developed within a multi-player environment, which selects for more extroverted, sociable gamers, while the temperaments include both extroverts and introverts.

So, for example, the “Socializer” term that makes sense within the Bartle Types for its emphasis on interacting with other people can seem not to apply to an introverted Idealist who prefers to play single-player games. These less-social Socializers are more likely to prefer individualized entertainment or abstract games, making it difficult to distinguish them from Rational/Explorer gamers. Closer study is usually required to see whether their primary reason for playing is to feel good (an Idealist preference) or to exercise their thinking skills (a Rational goal).

Chris Bateman’s DGD1 Model

Even taking introversion and extroversion into account, not everyone fits neatly into one of the four fundamental temperaments. This aspect of reality isn’t well described by the four-fold Bartle or Keirsey typologies. Some people feel equally drawn to Internals and Externals, or to Change and Structure.

The book 21st-Century Game Design, edited by Christopher Bateman, explores a “demographic game design” model (DGD1) of gameplay preferences that I believe forms a useful counterpoint to the Keirsey/Bartle model of general personality. Rather than matching each of the types and temperaments, the Bateman play styles appear to be secondary styles that fill in the gaps between the primary play styles.

All of the elements that Bateman defined for his four play styles as well as for the Hardcore and Casual modes appear to map not directly onto the Keirsey/Bartle map, but into each of the gaps between the four Keirsey/Bartle styles. The following diagram shows this overlaid relationship:

Unified Model, Keirsey-Bartle Diagram with Bateman DGD1 Model Overlaid

The value of the DGD1 model (beyond the utility it has in and of itself as a model of personality) is that it provides a direct response to one of the most common criticisms of the Bartle Types model, which is that “no one is ever just one ‘type’ of player.” The DGD1 model fills in the gaps between the Bartle Types. A gamer who knows that his preferred style of play is balanced between exploration and achievement, or a combination of Strategic (Rational) and Logistic (Guardian) play, who was told he “didn’t fit” the Bartle model, can now understand himself to be representative of the Conqueror play style as described by the interstitial DGD1 model. Rather than invalidating the Bartle Types, the DGD1 model deepens and refines that model of play styles, leading to the merged Keirsey/Bartle/Bateman model whose structure is shown in the diagram above.

Note: Following the publication of 21st-Century Game Design, a questionnaire for a DGD2 model was developed and added to the iHobo site. Drawing from lessons learned with the Myers-Briggs-based DGG1 model, the DGD2 model was built more explicitly around the four temperaments described by Keirsey. Rather than breaking or changing the play style model developed for DGD1, the application of concepts from Keirsey’s temperament theory appeared to sharpen the DGD-based Conqueror, Manager, Wanderer and Participant styles as complementary to the four Keirsey temperaments (and thus the four Bartle Types as well). (A subsequent model, BrainHex, follows a six-pattern typology.)

The Unified Model

As I explored the literature on player styles and models of gameplay, I was surprised to see how many of these other models proposed three or four categories. Even more remarkably, in many cases the descriptions given by the various authors for each of their categories sounded very much like the descriptions of the core play styles in the Keirsey/Bartle model.

As a result, the second major assertion I’m making in this article is that not only are the four Bartle Types a play-context subset of the four general Keirsey Temperaments, there are numerous other well-known models of play and game design that are also variations on the exact same set of four fundamental personality styles.

It’s important to acknowledge that there are other models of personality and play that do not appear to be variations on the same four essential styles. I understand that; I have no interest in trying to stuff every personality model I see into this one. As an experienced designer of systems, I’m very aware of the danger of seeing every phenomenon as a confirming instance of one’s pet theory. I’ve done my best to avoid that error by identifying as a facet of the Unified Model only those systems for which multiple elements appear to align closely with the other systems in the model.

This chart presents the basic concepts of each play style or personality model using words their creators selected as being generally representative of each worldview.

It’s intended to be an at-a-glance representation of the associations between styles of play and layered models of game design. It also references three general models of personality in functional group situations (usually the office or workplace), as well as three ways in which I’ve tried to boil down the four perspectives to their essential meanings.

Caillois and Lazzaro Meet Keirsey and Bartle

The first portion of the Unified Model chart links Keirsey’s general theory of human temperament to descriptions of the four primary styles of play given by Richard Bartle, Roger Caillois, and Nicole Lazzaro.

Note: Although Roger Caillois indicated that he did not consider the four styles he described to be a complete taxonomy, I respectfully suggest that he was closer to creating a good one than he knew. Along with his concepts of paidia and ludus, these six foci complete the “gaps” between the four core styles observed by others (as noted in the Unified Model). I therefore consider his observed styles to be part of that model, but the reader is welcome to disagree.

Caillois uses the term ilinx to describe the fun of “vertigo,” the adrenaline rush from pushing physical boundaries, which aligns to the sensation-seeking motivation that both Bartle and Keirsey describe for the Killer and Artisan styles, respectively.

Lazzaro’s “serious” or “visceral” fun (one of the four core emotional styles she identifies in her cluster analysis of emotional responses to gameplay situations) is also described as sensation-seeking — in particular, as seeking the feelings of excitement and relaxation that are the gut-level rewards for active play. Again, this aligns very closely with the pleasure the Artisan/Killer feels in the skillful manipulation of tools or people (External Change).

Both the ag?n of Caillois and the “hard fun” of Lazzaro are conceptually very close to the security-seeking motivations of Bartle’s Achiever and Keirsey’s Guardian.

Ag?n and hard fun are both about trying to obtain tangible, extrinsic rewards within the rules of a competitive game. This is the well-documented pattern of the

Achiever/Guardian, who lives life believing that it is necessary and right for the world to be well ordered and that the amount one wins should be directly

proportional to the amount of effort one puts into following the rules.

Caillois explicitly links mimesis to “simulation,” or the active construction of secondary realities. This is the hallmark of the creative Rational/Explorer. To a Rational, the fun of discovering or building new worlds is in mapping their unique characteristics through exploration, thereby enabling the comprehension of the internal structure of that new world. The Rational/Explorer interest in mimesis is thus associated with Lazzaro’s “easy fun,” which describes the distinct gamer preference for immersion in the world of the play experience.

Caillois describes the fourth mode of play, alea, as based on randomness and chance, imposing fairness on every player by making every outcome depend on the roll of a die or the turn of a card. This feels right to the Idealist/Socializer player, for whom the rules of the game may be nearly irrelevant and in which chance is acceptable or even necessary to evenly distribute outcomes. Rules are merely artifacts that enable interaction with other people (human or NPC). This aligns neatly with Lazzaro’s formulation of “people fun,” wherein the game world is treated not as a tool to be used, a challenge to be overcome, or a system to be understood, but as a social setting within which people can enjoy meaningful relationships with each other.

GNS+ and MDA+

In addition to these play style models there are two important models of game design that appear conceptually related to the Keirsey temperaments: the Gamist/Narrativist/Simulationist (GNS) model of game design originally conceived (though later deprecated) by Ron Edwards and the Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics (MDA) framework described by Hunicke, LeBlanc and Zubek .

The three-style GNS model aligns closely with three of the Keirsey/Bartle styles. The Gamist design style, which focuses on the mechanics or rules of play of a game, clearly matches the rules-oriented, competitive, hard fun-seeking Guardian/Achiever style. Similarly, Rational/Explorers are most likely to be drawn to the Simulationist design style that delights in the building of and immersion in complex and logically consistent worlds. And the human-centric, “people fun” storytelling impulses of Idealist/Socializers will usually be expressed as a focus on Narrativism as the primary means of making a game fun.

This leaves undescribed the preference for raw sensation. A fourth design style, which I’ve given the ungainly name of Experientialist, would emphasize play features that generate intense experiences — the definition of the sensation-seeking Artisan/Killer. If this Experientialist style is recognized as a valid game design interest along with Gamist, Narrativist, and Simulationist, then we have what might be called a GNS+ model that aligns completely with the Keirsey/Bartle and related models of play.

Adding this style to the GNS model is not an unsupported stretch on my part just to force GNS into the Keirsey/Bartle model. The Experientialist preference closely resembles the “Butt-Kicker” player type in the play style model suggested by Robin Laws. Enjoying play for its intense experiences is also directly analogous to the enjoyment of “vertigo” described by Caillois as a function of the desire for ilinx.

Something like this also applies to the MDA game design model. As with the GNS+ model described above, the MDA model seems to lack only a bottom-level design focus on the direct appreciation of action, which considers the gut-level sensations a game designer wants to elicit from players. I’ve suggested “Kinetics” as a name for this fourth style in what could be called the MDA+ model, where Kinetics once again aligns with Caillois’s ilinx preference for finding pleasure in action-oriented play.

(It’s interesting that the original GNS and MDA models both lack concepts describing play as a means of generating intense sensations.)

As with the original GNS model, the three layers of the MDA model align with play styles and personality types as described in the Unified Model chart. Mechanics, as the rules governing player actions, are the topic of choice for Guardian/Achievers who naturally take a Gamist approach to design. That’s where you find the answers for the ever-practical, “Yeah, but what do you actually do in the game?” question. Dynamics are of most interest to the Simulationist Rational/Explorer, who can’t help but focus on the functional behaviors of the game world that give it a unique life as a secondary reality. And the Idealist/Socializer, always operating according to an ideal vision for people, is most able to quickly grasp whether a particular game satisfies the Aesthetic requirements — does the game feel right?

With the theory explained, we’re now ready to look at practical uses for the Unified Model.

The Unified Model Explains Existing Games

An effective model should be able to explain how particular games satisfy particular play style interests. A good place to start is with popular first person shooter (FPS) games such as the Call of Duty or Battlefield franchises. These games feature high levels of graphical realism, a need for fast-paced tactical action in high-stress scenarios, real-world manual dexterity requirements, “whoa!” moments, clearly marked linear paths, vertigo-inducing set pieces, collectible achievements/trophies, and (in multiplayer mode) intense competition, role-based cooperation, and status markers on public leaderboards. All of these features are associated with externalities, and most are about directly physical experiences as opposed to abstract internal qualities such as thinking or feeling.

In a first person shooter, the high-speed, adrenaline-pumping tactical action for its own sake is aimed squarely at the externals-oriented Artisan/Killer play style preference. The externals-oriented Guardian/Achiever preference is addressed with clearly spelled-out operational rules, and with in-game intel items and achievements to collect as gameplay that gives purpose to the action. To the extent that a game emphasizes both of these elements to a high level of quality, that game will be embraced by Artisan/Killers and Guardian/Achievers. This combination lines up with the Casual mode of play in Chris Bateman’s DGD1 model. This might sound odd — the gameplay in pure FPS games is usually very intense — but it fits the concept of “casual” play as Bateman describes it, where there’s little emotional investment in the game world, players can drop-in/drop-out easily, the subject matter is concrete and easily relatable to well-understood phenomena, and the appeal is to a mass market.

Occupying the exact opposite position on the chart of play styles from real-time action/competition games would be adventure games such as Myst and The Longest Journey and creative games such as Minecraft or turn-based strategy games such as Civilization. These games, whose internal-oriented features emphasize both the story and puzzle play style preferences associated with feeling and thinking, are mirror images of external-oriented first-person shooter games that emphasize action and competitive accumulation. It’s reasonable to expect that most gamers who strongly prefer FPS games would be bored by adventure games, while most self-described adventure gamers find the typical FPS unsatisfying. This is precisely what the Unified Model would predict based on play style analysis, with Hardcore (story/puzzle) and Casual (action/loot) preferences on opposite sides of the Keirsey/Bartle/Bateman diagram.

If the Unified Model has validity, then it should also be able to explain the appeal of a “surprise” hit game like Minecraft. Still in beta at this writing, Minecraft has already earned the equivalent of tens of millions of dollars for its developer by emphasizing two play styles: creative exploration and exciting survival. While mapping cave systems or building structures (both highly discovery-focused activities), the player’s character may suddenly be attacked by hostile creatures. This generates the intense fight-or-flight reaction prized by Killers, who also enjoy the tangible (if virtual) sensations of destroying blocks, jumping from heights, and possibly falling (or being pushed!) into deadly lava.

The conjunction of the Rational/Explorer and Artisan/Killer play preferences corresponds to the Strategic/Tactical “Manager” play style of Chris Bateman’s DGD1 model.

Bateman describes the Manager style as being preferred by “a complexity-seeking player” who “can rack up serious hours on the games they really love,” and whose style is “associated with mastery and systems.” That neatly sums up Minecraft’s intense appeal to a specific subset of gamers who viscerally love opportunities to remake the game world to their own designs.

(It’s interesting to note that Minecraft’s primary designer has added achievements to the game, with an “adventure update” soon to be released. These new features should make Minecraft more appealing to Guardian/Achievers, who currently complain that Minecraft’s highly non-directed gameplay is — from their perspective — boring and hard to get into. Whether Minecraft can retain its Explorer-Killer focus after adding features that attract a host of highly vocal Achievers is a question worth exploring.)

Here’s a quick listing of where various game genres fit into the Unified Model:

One other possibility afforded by the Unified Model is to identify an individual’s natural play style through the games they report playing. This can work to the degree that individuals are invested in the “gamer” culture. The more they actively make playing new games a part of their lifestyle, the more accurately the play-focused Unified Model will predict their general personality style.

On the other hand, predictive accuracy can be extremely poor when trying to assess the personality style of someone who plays only a few light and generally popular games such as Solitaire. In this case, no model will be of much help since there’s just not enough information to work from. The emphasis of the Bartle Types on social players of multi-user games can also make those styles difficult to apply to someone who prefers single-player games.

Another possibility is that the individual’s choice of games to play may not fit neatly into one of the four major groupings. In this case, consider that they may play as one of the four types described by Christopher Bateman’s DGD1 model, where each type is a combination of two of the primary styles from the basic Keirsey/Bartle model.

In all these cases, the more games someone plays — they more they are immersed in the gamer culture — the more accurate the Unified Model can be in identifying their preferred personality style from the games they play. And the opposite is true as well: the fewer games someone plays, the less effective the Unified Model can be in identifying their natural personality style. This is not a deficiency in the Unified Model; it’s simply a lack of categorical information for the model to work with.

The Unified Model Helps Design New Games

The Unified Model by itself doesn’t talk about particular gameplay features. But it is possible to link gameplay features to specific play style preferences — different activities distinctively satisfy different needs. This allows designers to judge the fitness of various feature possibilities for a particular design goal.

Here’s a short list of representative gameplay features organized by play style:

UNIFIED Play Style ASSOCIATED GAMEPLAY FEATURES

Artisan/Killer/Experientialist action, vertigo, tool-use, vehicle use, horror, gambling, speedruns, exploits

Guardian/Achiever/Gamist

competition, collections, manufacturing, high scores, levels, clear objectives, guild membership, min-maxing

Rational/Explorer/Simulationist puzzles, creative building, world-lore, systems analysis, theorizing, surprise

Idealist/Socializer/Narrativist chatting, roleplaying, storytelling, cooperation, decorating, pets, social events

Let’s say you’ve been tasked with designing a game that’s “exciting” and has “lots of rewards.” From the chart above, you can see that “exciting” corresponds to the Artisan/Killer style, and “rewards” clearly describes the Guardian/Achiever preference. What you want, then, are gameplay elements that hit on both of those cylinders if possible, but on at least one or the other of them for sure.

So a satisfying concept for this game might be some form of arcade-style racing. This provides a highly physical environment where the player can directly manipulate a vehicle in a few very specific ways (but to a high degree of virtuosity) in order to be rewarded frequently. Making this the game’s core mechanic emphasizes both intense manipulative action and the satisfaction of simple, clear goals with collectible rewards, all of which speak directly to the two play style goals.

Highly physical and object-rich action games that satisfy Artisan/Killer and Guardian/Achiever desires are fairly common, though. So a stronger test of the Unified Model’s constructive power might be to consider combinations of play styles that aren’t often seen.

What about a game world that merges the Internal Change goal of Idealist/Socializers with the External Change desire of Artisan/Killers? (This would correspond to the “Wanderer” play style from Chris Bateman’s DGD1 model.) Such a game, without the Simulationist or Gamist structures preferred by Rational/Explorers and Guardian/Achievers, would likely appear to be a chaotic circus, a highly social environment where crazy things happen without warning. (Actually, this sounds very much like Second Life, doesn’t it? Could something like this work as a single-player game? What about as a Facebook game?)

Another unusual kind of game to create would merge the generally opposing preferences of Guardian/Achievers and Idealist/Socializers. (The corresponding merged type would be the “Participant” play style from the DGD1 model.) To build fully on its unique qualities, such a game would need to be designed to emphasize gameplay features focusing on the rule-based generation of social relationships and behaviors. This is gameplay that Achievers could appreciate for the interpersonal stability and “social leveling-up,” and which Socializers might enjoy as a powerful tool for creating stories about people. (Again, though, perhaps such a game already exists — isn’t this is exactly the play style combination provided almost uniquely by The Sims? Is there any way to make a Participant-style game that doesn’t seem to be a clone of The Sims?)

Conclusion

While no model of human behavior can ever be considered perfect, the practical question is only whether a given model provides sufficient explanatory and predictive power to allow game designers to communicate usefully about what gamers want, why they want it, and how to give it to them. By that measure, I believe the Unified Model I’ve suggested, with the DGD1 model of Chris Bateman superimposed, produces an overall theory of gamer preferences that does offer good explanatory and predictive power.

Some will naturally object to this or that aspect of the Unified Model, or to the entire concept of any personality model that “puts people in boxes.” For others, I don’t imagine this model will be considered a surprising revelation. Many of the individual associations have no doubt been observed by others, such as Ethan Kennerly’s exploration of the similarities between the Bartle Types and David Keirsey’s temperaments (brought to my attention by Richard Bartle from a MUD-Dev post by Kennerly in 2005). Christopher Bateman has also made linkages among many of the play style models detailed here in his DGD typology.

What I think the Unified Model uniquely offers is the insight that not just one or two but many of the most well-known theories of play style and game design are closely related to each other and to a general model of personality.

All of the creators of the various theories included in the Unified Model seem to be referencing the same deep human reality: there is remarkable agreement on the basic ways in which people want to express their playfulness as a function of a general personality style. By pointing out the single pattern shared by these models, my hope is to provide a framework for thinking about gamer motivations that will help developers create better games.

Still, if some other model can be shown to have better explanatory and predictive power, then I’ll enthusiastically set this one aside in favor of the new model. What matters is not that I’m personally “right,” but that anyone who is interested in making better games (and making games better) has the most powerful tools for accomplishing that task.

If someone can demonstrate a model for explaining and predicting why we play as we do that is easier to understand or more effective when applied than the model presented here, gamers and developers and publishers will all win.

Until then, I hope someone will find this Unified Model useful in designing and discussing games.

Appendix

The table below compiles information about each of the four styles expressed in multiple ways. Not only does this demonstrate the very close conceptual ties between each of the four styles as seen by the different model creators, it can serve as a guide for designing gameplay elements that satisfy specific play style requirements.

Note: With three exceptions, for the rows “Keirsey” through “Covey” the text in the third column is taken directly from books, articles, presentations or other documents written by the authors of each play style or personality model. The words used in the section on Caillois are taken from the translation of Les Jeux et Les Hommes into English by Meyer Barash. The words used for the GNS+ “Experientialism” and MDA+ “Kinetics” entries are mine, since those entries don’t exist in the three-fold models.(source:gamasutra)

上一篇:开发者不可重游戏玩法而轻图像设计

下一篇:游戏并非艺术 艺术推动游戏诞生

.jpg)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号