分享GDC 2011社交游戏座谈会的相关观点和评论

作者:Josh Sutphin

虽然今年GDC设有完整社交和在线游戏峰会,但我只参加其中两场:社交游戏合法性的辩论和年度演说座谈会,今年的主题是“社交游戏开发者奋力驳回”(游戏邦注:他们强烈怒斥去年GDC弥漫的反社交游戏态度)。

下面我将论述两次会议的相关论点,以及我个人的看法和回应,旨在纵览今年社交游戏所处位置。

促进社交互动

支持社交游戏的常见论点是他们促进真实世界的社交互动。Nabeel Hyatt(Zynga)讲述一个趣闻:一群40岁的家庭主妇每周都要碰面一起玩社交游戏,他将此称作LAN派对。Curt Bererton(ZipZapPlay)称社交游戏提高自己同好友和家人的互动;他还谈到游戏礼物,如定制贺卡、纸杯蛋糕及其他道具,可以促进游戏之外的沟通。

Brian Reynolds(Zynga)表示,他参与社交游戏主要是由于他喜欢Facebook,社交游戏给予大家更多社交互动渠道。他还表示该领域的一个吸引之处在于相比传统游戏,这些内容覆盖更广泛、更多元化的用户群体。但和传统游戏一样,他觉得社交游戏充满有趣选择、模式、探索和惊喜。他认为社交游戏还有待继续发展,但其所处的是正确发展轨道。

我理解这些观点,我赞同认为宣传社交互动是件好事的观点。但我不确定反对社交游戏的群体是否也反对促进社交互动,他们也没有明确说明社交游戏存在不可取的品质。突出社交游戏的这一特点似乎是为了规避争论。

合法性的讽刺意味

Hyatt提出一个有趣观点:游戏行业已在谋求合法地位的道路上斗争了几十年,但如今其似乎开始致力于排挤社交游戏。 Ryan Henson Creighton(Untold Entertainment)称我们常常炫耀游戏获得的收益超越好莱坞,但当Zynga出现,赚取大把收入,我们又开始抱怨其不该如此。Brenda Brathwaite(Loot Drop)提醒大家,行业之遇到诸多类似冲突,团结一致会让我们变得更强大。

这些都是发人深省的观点,似乎有些凸显社交游戏批评者的虚伪。从某种程度看,这是个“自相矛盾”的观点:我们过去希望游戏能够同其他媒介平起平坐,被视作正当艺术和业务,能够获得丰厚收益,覆盖广泛族群,而现在当一切已经实现,我们却举起双手表示,“等等,这不对”。

但从某种程度看,这存在问题。当Bererton开始谈论社交游戏的艺术成就,Ian Bogost(游戏邦注:来自乔治亚理工学院)打断问到,“艺术在哪里?”他获得在座多数人的共鸣:他们纷纷觉得社交游戏的执行情况应该获得有效改善。我们变成主流趋势,得到文化认可,获得可观收入,但我们也失去某些元素。当然我们促进玩家展开沟通,但就像Bogost说的,我们其实是把好友转换成资源。这是否是社交游戏的终极表达?这是否是我们的期望目标?我想多数人一定都会果断表示,“不!”

反馈参数 Vs. 闭门造车

Hyatt简要论述反馈参数,虽然其在评论之外丝毫未谈及此话题,他还是指出其中优点。他表示参数能够让游戏设计师走出象牙塔,创造设计更新的反馈循环机制,这些设计更新主要迎合用户需求,而非来自设计师的凭空想象。

对业内众多人士而言,“参数”似乎是个忌讳字眼。但就像Bererton曾提醒我们的,参数运用有好有坏。就我看来,设计师和数据的正确关系应该是设计师通过数据获悉玩家主观体验,但基于自身目标而非玩家偏好做决策。设计师的目标是游戏的灵魂,是最基本的表达。若你将此出卖,任由参数决定决策,游戏就会变得毫无灵魂。

但公平来看Hyatt的观点,若你完全忽视数据,你就无法知晓千里之外的玩家所体验的内容是否就是你想要传递的,你将很容易忽视这点。参数是我们比较主观体验的渠道。内容常无法以预期方式进行,不是由于构思失败,而是由于执行环节存在问题。

克隆领域

社交游戏近年的主要批评声集中在行业充斥克隆作品。Zynga受到的质疑尤其突出:批评者声称《FarmVille》是《Farm Town》的仿制品,《CityVille》也存在《Social City》的影子。

Hyatt反驳此指控,他表示第一人称射击游戏都非常相似,电视情景喜剧的模式也几十年来从未改变。他认为这说明开发者找到符合用户口味的内容,所以只要这持续奏效,他们就会继续提供。他指出,《FarmVille》和《CityVille》都有在先前作品基础上添加创新元素。

Daniel James(Three Rings)支持社交游戏批评观点。他表示,疯狂复制是传统游戏开发商避开社交游戏领域的主要原因。他还指出,克隆文化令意图涉猎社交游戏领域的独立开发者处于艰难境地:独立开发者的唯一出路就是创新,但随后大型实力雄厚公司就会跟进,更好落实创新构思,从而挤压独立开发者的生存空间,这些开发者目前已其毫无竞争优势。

Scott Jon Siegel(Playdom)极力评判自己所处的行业,称社交领域2年前的状况要比现在好很多。他表示,2年前社交游戏充满创意和创新,还举例《Parking Wars》、《宝石迷阵闪电战》和《Mouse Hunt》。他认为这些都是非常有趣的游戏,但随后出现《Farm Town》,行业就开始注视这款游戏的成功。他表示,“2年前我们向右急转,然后再也没有回头看。我们需要重新开始。”

这也许就是我对社交游戏的最大不满之处。《Farm Town》模式(游戏邦注:随后又因Zynga的《FarmVille》变得生生不息)似乎已经成为现代社交游戏的蓝本。但我们目前正在探索新平台和新范式,旨在呈现前所未有的内容。

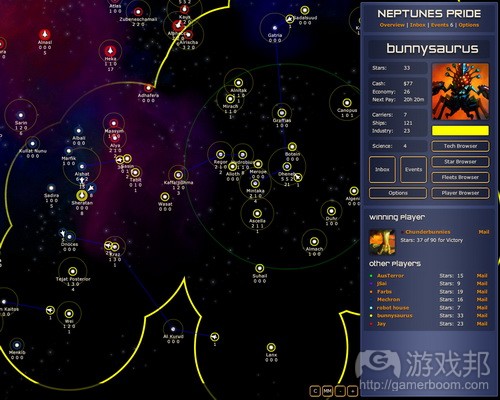

我想知道为何诸如《Neptune’s Pride》和《Blight of the Immortals》之类的游戏从未出现在社交游戏会话中,为何鲜少社交作品采用此模式。我想知道为什么社交游戏总是将好友当作资源,而不是真正地展开共同体验。我想知道为何社交圈仍旧被当作病毒式营销工具,而非可靠玩法。我想知道为何社交游戏和ARG游戏(候补现实游戏)没有相互融合。我想知道为何社交游戏没有试图引入新构思,教授玩家新技能,或者引导他们互相了解。我想知道为何社交游戏费尽心力地限制玩家互动,只是简单追求“日点击量”。我想知道为何社交游戏满足于劳动构想,为何不鼓励用户追求更多内容。最重要的是,我想要知道为何社交游戏并非真的具有社交性。

总结

我对社交游戏合法地位持怀疑态度,今年的GDC我依然坚持此立场。但经过此次大会,我的确就社交游戏正面论点有了深入了解,能够更客观谈论此话题。

我明白的一点是,社交游戏领域确有设计师不满意行业当前情况,他们积极纠正当前模式存在的缺陷,促使社交游戏变成真正具有“社交性”,真正成为“游戏”。就像Brenda Brathwaite说的那样,“我看到露天采矿者人也开始加入游戏领域。他们不是我们中的一员,他们也不是源自我们的行业。”虽然这些设计师的劳动尚未看见成果(至少没有带领社交游戏步入我所希望看到的轨道),但至少令人欣慰的是,还有业内人士不满社交游戏当前态势。

游戏邦注:原文发布于2011年3月12日,文章叙述以当时为背景。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

GDC 2011: Social Games Panels

by Josh Sutphin

This article is a bit late on account of my return from GDC dropping me straight into a pretty insane work-week, and also my random decision to re-do the site last weekend (hooray for priorities!)

While there was an entire Social and Online Games Summit at GDC this year, I attended just two sessions: a debate on the legitimacy of social games, and the annual rant panel for which this year’s topic was “Social Game Developers Rant Back”. (They’re ranting back against the anti-social games attitude that was prevalent at last year’s GDC, if you were wondering.)

Instead of just writing up my notes on each session, I’m going to merge together the various arguments from both sessions, along with some of my own opinions and responses, in an attempt to get a little broader look at this year’s view of social gaming.

Driving Social Interaction

One oft-repeated argument in favor of social games was that they drive real-world social interaction. Nabeel Hyatt (Zynga) related an anecdote about a group of 40-year-old housewives who meet every week to play social games together, saying it resembled a LAN party. Curt Bererton (ZipZapPlay) indicated that social games have increased his own interaction with friends and family; he also talked about how in-game gifts like customized greeting cards, cupcakes, and other items can act as triggers for out-of-game conversations.

Bryan Reynolds (Zynga) said that he got into social games mainly because he loves Facebook, and that social games are doing audiences a service by giving them more ways to socialize. He also suggested that part of the attraction of the space is that it reaches larger and more diverse audiences than traditional games. But like traditional games, he asserted that social games are full of interesting choices, patterns, discovery, and surprise. He did admit that social games aren’t yet where he wants them to be, but he seemed convinced that they’re on the right track.

I understand these perspectives, and I agree that promoting social interaction is a good thing. But I’m not sure any arguments against social games also include arguments against promoting social interaction, nor do they suggest that social games have absolutely no redeeming qualities whatsoever. Highlighting this feature of social games seems like it’s evading the debate.

The Irony of Legitimacy

Hyatt raised an interesting point: the games industry has fought for decades to legitimize itself (with a great deal of success) but now seems hellbent on de-legitimizing its own social games sector. Ryan Henson Creighton (Untold Entertainment)[1] noted that we often brag about games making more money than Hollywood, but when Zynga comes along and makes a lot of money we complain that it shouldn’t be this way. Brenda Brathwaite (Loot Drop) reminded the audience that our industry has dealt with many similar conflicts before[2], and that we always came out stronger when we banded together rather than fracturing apart.

These are thought-provoking arguments which seem to highlight some hypocrisy by critics of social games. To a certain extent, this is the “You made your bed, now sleep in it” argument: we wanted games to take their place alongside other mainstream media, to be considered legitimate art and legitimate business, to make a lot of money and to touch millions of lives… and now we’re here, and we’re holding up our hands and saying, “Wait, no, this isn’t right.”

But to an extent, it isn’t right. When Bererton started talking about the artistic merits of social games and Ian Bogost (Georgia Institute of Technology) cut in with a snarky, “Where’s the art?” he captured the feelings of many of us in the room: that the idea of social games has much more potential than their modern execution has bothered to realize. We got mainstream, we got culturally legitimate, and we made a lot of money, but we lost something somewhere along the way. Sure we’re connecting people, but as Bogost said, what we’re really doing is turning our friends into resources. Is that the ultimate expression of social games? Is that what we really wanted to achieve all this time? I think for most of us, the answer is a resounding “No!”

Metrics vs. The Ivory Tower

Hyatt talked briefly about metrics, and while there was (curiously) almost no discussion on that topic outside of his own comments, his point still merits examination. He asserted that metrics bring the game designer out of the ivory tower, creating a feedback loop for design iteration that attends to the needs of the audience rather than the whims of the designer.

For many in the industry, “metrics” seems to have become a dirty word. But as Bererton at one point reminded us, metrics can be used for good or for evil. In my opinion, the correct relationship between the designer and the data is that the designer should use the data to understand the player’s subjective experience, but make decisions based on what the designer means to communicate and not what the player prefers. The designer’s vision is the soul of the game, its fundamental expression. If you trade that away and let the metrics control your decisions, you might end up with a commercially successful game, but it will still be a soulless one.

But to be fair to Hyatt’s point, if you ignore the data entirely then you really have no idea if the player is experiencing anything remotely like what you intended to express, and you’re liable to miss the mark entirely. Metrics are a means by which we can compare subjective experiences. That they’re often not used that way is not a failing of the concept, but of its execution.

An Industry of Clones

One of the most common criticisms of the social games space in recent years has been that they are an army of clones. Zynga in particular has come under fire for this: critics claim a clear lineage from Farm Town to FarmVille, from Social City to CityVille, and so on.

Hyatt defended this accusation by asserting that first-person shooters are all quite similar and that the formula for TV sitcoms hasn’t changed in decades. He said this indicates that those creators have found something that works for their audiences, so they’ll keep providing that for as long as it keeps working. He also asserted that FarmVille and CityVille have in fact built new innovations on top of their predecessors.

Daniel James (Three Rings) was more sympathetic to this criticism, indicating that the perception of rampant, outright cloning is a major factor in traditional game developers shying away from the social games space entirely. He also noted that a culture of clones creates a very difficult environment for independent developers who might want to get into social games: an indie’s only recourse is to innovate, but then a huge, well-established company (like Zynga?) comes along and better executes that innovative idea, effectively killing the indie which is now in no position to compete.

Scott Jon Siegel (Playdom) railed enthusiastically against his own sector, asserting that social games were in a much better place two years ago than they are today. Two years ago, he said, social games showed signs of creativity and innovation, citing games like Parking Wars, Bejeweled Blitz, and Mouse Hunt. He said these were genuinely interesting games, but then Farm Town came along and the industry became totally fixated on that game’s success. “Two years ago we made a hard right turn and never looked back,” he said. “We need to start over.”

This is probably my biggest complaint about social games. The Farm Town formula, subsequently immortalized by Zynga in FarmVille, seems like it’s become the de facto blueprint for the modern social game. But we’re looking at a platform and a paradigm which are capable of things games have never been capable of before!

I want to know why games like Neptune’s Pride and Blight of the Immortals never seem to come up in conversations about social games, and why so few social games work that way. I want to know why social games are about using your friends as resources, rather than truly playing with (or against) them. I want to know why the social graph is still seen as a tool for viral marketing and not an honest gameplay opportunity. I want to know why social games and ARGs don’t have a million times more cross-pollenation. I want to know why social games don’t try to introduce people to new ideas, teach them new skills, or even guide them to discover things about each other. I want to know why social games go so far out of their way to limit your interaction, literally down to “clicks per day”. I want to know why social games are content with the fantasy of labor[3] and why they don’t encourage their audiences to aspire to more. And most of all, I want to know why social games aren’t actually fucking social.

Conclusion

I was a major skeptic of social games going in, and this year’s GDC didn’t really change that. However, I did return with a a better understanding of (if not agreement with) the arguments in favor of social games and (I think?) an improved ability to articulate myself on this topic.

One thing that became clear to me — and in retrospect it should perhaps have been obvious — is that there really are designers in the social games space who are not happy with the modern social game, and who are very passionate about moving that form away from its present failings and into a future where social games do much better both at being “social” and at being “games”. As Brenda Brathwaite said, “I have seen the strip miners and their entry into games… They are not one of us, nor are they from us.” And while I haven’t yet seen these designers’ labors bear fruit — at least not in the sense of moving social games in the direction I personally would like to see them go — it is at least comforting to me to know that there are people within the space who are as critical of it as the rest of us.(Source:third-helix)

下一篇:分享社交游戏开发的10点建议

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号