解析社交游戏设计之盈利性

作者:Gregory

社交游戏开发商及发行商通常所说的社交游戏三大特性是病毒性、盈利性和留存率。本文我们将谈谈社交游戏的盈利性。

有些人可能会认为盈利性不属于游戏设计范畴,这是营销、销售和运营部门应该解决的事情。我知道这些人选择设计工作是为了尽可能地制作出最佳游戏,但他们也需要维持生计。而且,我相信如果设计师将盈利性融入游戏设计中,其效果会提高10倍。这个话题的内容很多,可能足够写一整本书,因而本文只能阐述某些重点内容。首先是对整个话题的概述。

多数游戏采用以下这些盈利方法:单次购买;广告游戏;片段内容和付费解锁;订阅;虚拟商品。

社交游戏并不能采用上述所有方式。比如,单次购买就不是种适合于社交游戏的赚钱方法。其他游戏都是免费的,因而你也不能要求玩家先行付款,这会导致游戏为玩家所忽视。你可以使用下载游戏暂时免费(游戏邦注:通常设定游戏下载后60分钟内免费)这种已证实有效的模式,随后再向玩家一次性收取费用,但这种方法仍旧不太适合当前环境。在社交游戏中,你需要的是玩家不断玩游戏并不断招募他们的朋友。

虽然广告游戏在社交网络上行之有效,但它们很难为游戏开发商带来营收。对那些希望通过游戏来做广告的公司来说,可能会是另一番景象。作为游戏设计师,我认为这只是种无法获得最大收益的劣等方法。不过如果你将其与其他方式(游戏邦注:如虚拟商品)相结合,或许结果会有所不同!

单纯的订阅模式在社交网络上也无法施行,原因多半与单次购买相同。其他游戏都免费而且较小,你有可能在社交网络上发布的休闲游戏似乎并不值得用户付费订阅。

片段内容和付费解锁可以稳定地让社交游戏盈利,难点在于决定锁定或不锁定游戏哪些部分的内容。你需要足够内容来吸引玩家,但还得保留足够丰富的内容供玩家解锁。随着时间推移,你能增加的内容越多越好。刚开始你可以设定少许付费内容或完全免费,只要你可以稳定增加新付费内容,你的游戏就有可能带来可观的收入。免费增值模式的一半是片段内容。

虚拟商品是目前我最喜欢的社交游戏盈利方式。游戏免费,但有某些可以收集、使用或供玩家角色穿戴的道具或物品。几乎所有的流行社交游戏都会向玩家出售虚拟商品。虚拟商品是免费增值模式的另一半。

片段内容和虚拟商品二者都必须设计到游戏中,以呈现其最佳效果。后期再添加进去是件很难的事。那么,如何才能让它们发挥最佳效能呢?

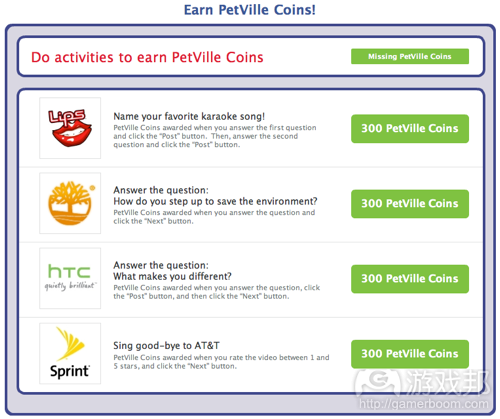

很显然,如果你想通过社交游戏赚钱,就必须要有说服玩家在游戏中花钱的方法。实现上述目标主要有两种方法,直接付费(游戏邦注:玩家给你邮寄支票或用信用卡支付)或让玩家替你“工作”。我在这里用引号的原因在于,你可能不会把玩家所做的事情当成是工作。通过第三方公司,玩家在某物上投入的时间和注意力会为某些人产生价值(游戏邦注:因而称之为“工作”)。这些行为也可以直接为你产生价值,但通常你所专注的是游戏制作而不是收获网民的工作成果。所以,第三方公司会让玩家去做某些工作,然后支付你一定的报酬。你给玩家提供游戏内的物品作为回报,循环就此结束。此类协议的行业术语称为“offer”。

现在,你有两种让玩家为了在游戏中获得更多内容而向你付费的方式。你要如何为他们提供回报呢?你可以在他们完成offer后提供个人奖励,或者让他们通过信用卡直接购买各种奖励。然而,这其中存在某些问题。如果采用offer这种方式,面临的问题是将offer价值标准化较为困难。offer供应商可能会有多个价值各不相同的选择。如果强行为这些offer制定标准,你也会损失部分盈利,比如为某个简单的offer向玩家提供过高的报酬。如若不然,你就只能接受数量极其有限的offer,玩家可能无法找到能吸引他们的offer(游戏邦注:也就是他们喜欢的“工作”)。如果采用让玩家通过信用卡(游戏邦注:或paypal等支付方式)购买的方式,向玩家出售每件小东西说服其购买可能会让他们感到厌烦。而且在信用卡交易中,你可能还需要设定最小购买金额(游戏邦注:因为在此过程中开发商也要支付费用),这严重限制了你能出售给玩家的东西。

这些对零售游戏或传统下载游戏等单次购买游戏来说并不是问题,但我们此刻正在讨论的是社交游戏,在这个行业微交易才是真正的霸主。上述所有限制因素导致我们需要采取中间步骤,使用游戏内货币来将玩家不同数额和用于购买各种资源的付费聚集起来。然后,玩家可以用不同数量的此类付费货币来购买游戏中他们想要的东西。进出货币数量自由化极大地改善了系统效能,使交易双方都很满意。

使用付费货币还有其他优势。拥有不熟悉的货币可以让玩家产生某种重要的心理作用。以美国为例,每个人都知道1美元的价值,这是大家天天在用的钱币。但是日元和你游戏中的付费货币等其他货币的价值不那么确定。此类货币的价值用户并不清楚,因而带有些许神奇特性。这是为何人们在国外度假时花钱更加随意的原因之一,他们无法快速计算出物品用本地货币来衡量的价值,在心理层面上并不知晓外币的本质价值。游戏中付费货币的情况与上述类似。

在为社交游戏设定付费货币时,你需要决定货币间的兑换率。玩家用他们的美元、欧元、日元或比索换得多少游戏内付费货币?很显然,兑换率最好不是1:1。兑换率要让用户难以换算,所以我不建议使用10或100之类的比值。看看某些成功的主流付费货币,XBOX live的兑换率是80:1,Nexon上是760:1。用这些大数值有两个原因:让玩家产生价值感;减少游戏中最小商品的定价。当你花5美元购买400个付费货币时,你觉得自己做了笔合算的买卖。当你在游戏商店中购物,看到某些售价仅10个付费货币的商品时,你觉得自己完全可以买得起。这换算过来只值几美分,你都懒得去算了,直接点击“购买”然后继续游戏。

在含有微交易和虚拟商品的免费游戏中,为何你不该将所有东西用来出售呢?如果玩家有意愿购买,难道不应该定价销售吗?我见过许多社交游戏行业的人带有这种想法。然而,我坚信对上述问题的回答是否定的,你不应该这么做。我要尽量让其他人相信,每款游戏中都应该有无法购买的可获取东西。我认为,拥有此类东西会使你的整体盈利有所增加,即便你并未出售这些东西。那么,我所说的有价值却无法购买的东西是什么呢?玩家要如何才能获得这些东西呢?他们可以赚取此类东西。你的游戏中应该要有通过在游戏中投入大量时间来赚取的东西。

这种做法是如何发挥作用的呢?如果玩家可以花钱购买想要的所有东西,某些人确实会这么做。他们拥有所有东西后会觉得你的游戏中再也没有想要的东西,这部分玩家就会离开游戏。你固然从他们身上赚到了钱,但离开的这些人可都是你的大客户!你想要的是让他们在游戏中停留尽可能长的时间,这样就可以不断为你产生大量盈利。如果他们可以购买所有东西,你就会失去他们。你需要的是某些他们不能购买的东西,这样他们就有继续玩游戏的理由。

提供只能赚取的东西也对非付费玩家有所帮助。这些玩家需要的感觉是,他们能够与那些购买所有东西的富人竞争。如果有必须通过赚取来获得的东西,赚取此类东西会让非付费玩家产生良好的感觉,有时他们的脚步比某些付费玩家还要快。你用这些东西来奖励他们对游戏的忠诚以及投入的时间。这会让他们继续玩下去,他们玩的时间越长,你把他们转变为付费玩家的可能性也就越大。而且,如果只能赚取的东西确实很棒,他们会逐渐觉得这个游戏有一定的价值,可能会因此改变想法投入金钱(游戏邦注:付费原因不再是“我想要XXX”)。我觉得现在已经无需再详细解释为何游戏需要非付费玩家的原因了,要点有两个:他们会让付费玩家加入到游戏中;他们可以为付费玩家提供某些内容(游戏邦注:在互动游戏中)。

我相信多数免费游戏需要设计两种不同货币的原因在于,它们总少不了只可通过赚取而得的东西。一种货币用来购买付费道具,另一种用于支付可赚取的道具。重点在于这两者之间不可直接转化。许多免费游戏允许玩家直接或使用付费货币来购买赚取货币,这种做法从一开始便使设置两种货币的主要目的形同虚设。

双重货币系统还催生出第三种道具,即可以用两种货币来购买的道具。以下举个我最喜欢的例子:在《英雄联盟》中,你可以购买额外的角色。上图显示部分商店内容。我们可以看到有5个角色正在出售,每个都有两种价格。第一个价格是付费货币,第二个是赚取货币。很显然,你会看到赚取货币的数值较大,花钱的速度比赚钱要快得多。你还会看到某些角色的付费价格相同但赚取货币价格却不同。

这种做法有何效果?为何为角色制定两种价格对游戏如此重要?对你来说,这是让玩家陷入是否要花钱的重要抉择的绝佳方法。有些玩家不打算花钱,因而他们尝试自行赚取所有想要的东西。他们在购买角色的时候想道:“我每天赚500,1周时间后可以解锁Shen,或花两周时间来购买Malzahar。买下我想要的所有角色需要花6个月的时间。我可以做得到,所以无需付费。但是如果我现在只购买Malzahar,就可以省下两周时间,也会更快得到Kennen。”除此之外,这款游戏中还有只能通过赚取货币购买的重要道具。玩家自然也会考虑到这些内容:“如果我现在省下6300个赚取货币,我就可以更快拿到自己需要的Runes(游戏邦注:只能赚取的道具)。但是我现在买不起那些东西,或许我应该买自己可以买的东西。”

使用这种双货币、赚取道具和可通过两种货币购买道具的系统,你会让玩家产生此类思考,增加他们首次付费的可能性。他们感觉自己可以赚到所有东西,但知道自己等不了那么长的时间。他们意识到时间就是金钱,随后会认为值得在你的游戏中投入金钱。

游戏中所有东西只通过一种货币出售,会让上述所谓的非付费玩家觉得游戏只适合那些有钱人,他们也就不可能在游戏中待到购买抉择时刻。如果没有赚取宝贵商品的方式或某些只能赚取的道具,玩家可能不会产生付费购买的念头。即便对那些从玩游戏第一天起便有意愿付费的玩家,这些计算也很有意思,他们知道可以赚取某些道具而不用付费购买所有东西,这让他们感到愉快而且对你的游戏更感兴趣。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Social Game Design: Monetization

Gregory

As I stated last time: social game creation and distribution companies often discuss three important qualities of a game on a social network. Virality, Monetization, and Retention. Today’s topic is monetization.

What? You say that monetization isn’t a game design topic? That’s for marketing, sales, and business departments to handle? Look, I know you’re in the design business for the pure love of making the best possible games, but you’ve gotta eat too, right? Also, I believe monetization works ten times better if it is integrated into the design of the game by the designer. This topic is so huge I could probably write a book about it, so I must choose to narrow my focus for this first post about it. Today will be more of an overview and starting point for the topic that I will come back to from time to time.

Most games are monetized in one of these ways: Single (one-time) purchase; Advergames; Episodic content and paid unlocks; Subscription; Virtual Goods.

Social network games do not mix well with all of these methods. Single-purchase, for example, is a terrible way to make money in social games. All the other games are free, so you can’t ask for money up front, you’ll just get ignored. You could use the established download game model of free for a while (commonly 60 minutes for download games) and then charge the one-time fee, but it’s still a lousy fit for the environment. In social games you need players to keep playing and keep recruiting their friends.

While Advergames can work on social networks, they are pretty inefficient ways to make money for the game builders. For the company that desires the advertising it might be another story. As a game designer, I find this is just a sad way to leave a lot of money on the table. If you want to combine it with other methods (like virtual goods) that would be another story!

Pure subscription models also don’t work well on social networks for a lot of the same reasons single-purchase doesn’t work. The other games are all free and the smaller, more casual games you’re probably making for social networks don’t appear to be worth the price of a subscription. (Yes, I know you might be making more money with a virtual goods model than a subscription – but we’re talking about how it feels to players, not about reality.)

Episodic content and paid unlocks are a solid way for a social game to make money. The hard part is deciding what parts of the game will be locked and which parts will not. You need just enough to get players hooked, but still have enough meaty options for them to unlock. The more content you can add as time goes on the better. You can start with little or perhaps nothing for pay and so long as you can keep to a solid schedule of adding new content for pay your game may thrive. Episodic content is half of the “freemium” model.

Virtual goods are by far my favorite way to monetize a social game. The game is free, but must include items or objects that can be collected, used, or (often) worn by player characters. Almost all (if not all) of the best known social games sell virtual goods to their players. This is the other half of the freemium model.

Episodic content and virtual goods both must be designed into the game to perform at their best. It’s hard to add them later. How to best use them? That’s a topic for another day.

It should be obvious that if you want to make money from a social game there has to be a way for the player to put money into the game. The two major ways for this to happen are direct payment (they mail you a check, or input their credit card information) or they can do “work” for you. I use quotation marks there because what players do is not something you might consider work. Usually through a 3rd party, the player spends their time and attention on something that results in the generation of value for someone (hence “work”). It could be direct value to you, but usually you’re busy trying to make a game, not harvest the work of the internet masses (if you wanted to run wikipedia, well, I hear that job’s been taken.) So this third party asks the player to do some work and in exchange the third party pays you money. You complete the loop by giving the player something in your game. The industry term for these arrangements is “offers.”

Now you have two methods for players who want more out of your game to give you money. What are you going to give them in exchange? You could offer them individual rewards for each offer they complete, or let them purchase each reward directly with their credit card. There are some problems with this, however. On the offers side, it can be difficult to standardize the offers to be of equal value. The offer providers will have many options that are not of equal value to them. If you force a standardization on them you’ll be leaving money on the table – sometimes overpaying a player for a less-idea offer. Either that or you’ll only be accepting a very few offers, and players won’t be able to find an offer they find attractive (“work” that fits their preferences). On the credit card (or paypal, etc.) side, if you ask the player for direct payment for each little thing you sell them they will be annoyed. Also you’ll probably want a minimum purchase amount on a credit card transaction (you pay fees on those, after all) which severely limits what you can sell to the player.

For a single purchase game, like a retail game or a traditional download game these wouldn’t be big issues, but we’re talking about social games here, where the microtransaction is king. All of this leads us to the need for an intermediate step, a currency within the game that can aggregate the player’s payment in different amounts and from a variety of sources into one place. Then this paid currency can be used by the player in various amounts to buy things in the game that they desire. Freeing up the amounts both coming in and going out vastly improves the efficiency of the system and the happiness of all parties involved.

Using paid currency has other advantages as well. There is a significant psychological effect on the player of having a currency they are not natively familiar with. In the United States (for example) everyone knows the value of a dollar – it’s the money they (we) use every day. Another currency, anything from yen to your game’s paid currency, is less solid. The value of it is less clear and it has a bit of a fantasy quality. This is one reason people tend to spend more freely when on vacation – they can’t quickly calculate the value in their native currency, and the foreign currency doesn’t hold that intrinsic-value grip on their psyche. The paid currency in your game will act the same way.

When setting up a paid currency for your social game you will need to decide the conversion rate. How much of your game’s paid currency does a player get for their dollar (or euro, yen, wan, peso…)? I hope it’s obvious they should get better than 1 for 1. You want to make it difficult for them to convert, so I would avoid all strict factors of ten. If you observe some major and successful paid currencies you’ll see numbers like 80:1 (XBOX live), or somewhere in the 760s:1 (Nexon). The two biggest reasons for these inflated numbers are: giving the player a feeling of value, and reducing the size of your smallest price. When you pay $5 and get 400 paid currency you feel like you’re getting a good deal. When you’re shopping in the game’s store and you see something for a mere 10 paid currency, you feel you can easily afford it because that’s what? Some small fraction of a dollar that you can’t be bothered to calculate because you’ve already clicked “buy” and moved on.

In a free to play game with microtransactions and virtual goods, why shouldn’t you sell everything? If players are willing to buy it, shouldn’t you put a price on it and sell it to them? I have seen this attitude in a lot of people in the social games industry. Yet I strongly believe the answer is, no, you should not. I have had to fight to convince others that there should be desirable things in every game that cannot be bought. I will argue that having such things will actually increase your overall revenue, even though you’re not selling them. So what do I mean by things that are valuable but can’t be bought? How do players get them? They earn them. Your game should have things that are earned by playing the game, preferably by playing it a lot.

How does that help? If players can buy everything the want, some of them will do exactly that… and then they will be done. They have it all, and they will shortly find that your game holds nothing more for them and they will quit. Sure, you got some money out of them – but these were your big spenders, your whales! You want them playing as long as possible so they’ll keep giving you large sums of money. If they can buy everything right away, you’ll lose them. You need some things they can’t buy so they’ll have a reason to keep playing.

Providing earned-only things also helps the non-paying player. This player needs to feel they can compete with the rich kid next door who buys everything. If there are cool things that must be earned, the non-paying player can feel good about earning them (sometimes ahead of some number of paying players). You are rewarding their loyalty and commitment to the game with a cool thing. This keeps them playing longer, and the longer they play the more time you have to convert them to a paying player. Also, if the things they can only earn are really cool, they will have increased feeling that this game is “worth it” and might change their mind about putting in money for that reason (instead of the reason of “I want X”). Do I also need to explain why you need non-paying players in your game, even if they never pay? I shouldn’t need to, but here are two reasons: They tell paying players to come play, and they provide content (in any interactive game) for the paying players.

Needing earned-only things leads to the reasons why I believe two separate currencies is ideal in most free-to-play games. One currency for paid items, and the other for earned items. It is important that there is not any direct way of converting one to the other. Too many free-to-play games allow players to purchase the earned currency either directly or using the paid currency. That removes the main purpose of having separate currencies in the first place.

Dual currencies also leads to the third (and equally important) type of item for sale: the item sold for both currencies. Here’s one of my favorite examples: In League of Legends you can buy extra characters to play. The above image shows part of the store. We can see five characters for sale, each of which has two prices. The first price is in paid currency (the fist), and the second is in earned currency (swords). Obviously, your math should always work out so that the earned currency numbers are bigger, making purchasing feel efficient (compared to earning). Also note that some characters have the same paid price, but different earned prices, or vice versa (I think Garen was on sale at this time).

What does this do? Why is it so important to have two prices on these characters? It leads your players into the critical decision point of whether to spend money or not in a way that is most excellent for you. The player wants to own many, if not all of these characters (because your game design is good – a topic for another day). This player didn’t plan on spending money, so they are trying to earn them all. They come to buy a character and they start calculating: “I earn 500 a day, so it takes me a week to unlock Shen, or two weeks for Malzahar. It’s going to take me six months to get everyone I want… I can get there, so I don’t have to pay, but if I just buy Malzahar now I’ll save myself two weeks and be able to get Kennen that much faster.” In addition, there are important items in this game that must only be earned. This also enters the player’s thinking: “If I save 6300 earned currency now, I’ll be able to get the Runes (those earned-only items) I need that much faster. I can’t buy those, so perhaps I should buy the thing I can buy.”

With this system of dual currencies, items that are earned-only and items that can be obtained in both ways (and proper pricing) you can lead players into this pattern of thinking, which increases the chance they will make their first purchase. They feel they could earn it all, but they know they don’t have that much time, and they realize that time is money, and decide that your game is worth the monetary investment.

If the non-paying player in my story above felt the game was “only for rich kids” because everything was sold up front, for one currency, they would not have played it long enough to reach the purchasing decision point. If there were not ways to earn the valuable goods, and if there were not some earned-only items the player might not go through as many “pros” to making the purchase in their mind when they reach the decision point. Even for players willing to pay from the first day, these calculations are interesting and knowing they will earn some items and not have to pay for everything makes them happy, and more interested in your game. (Source: Design-Side Out)

上一篇:社交游戏尚未真正融入社交玩法

下一篇:解析社交游戏设计之病毒式传播功能

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号