美国CTIA提议为手机应用制定统一评级系统

作者:Josh Lowensohn

无线行业贸易组织想对手机应用进行评级,帮助家长杜绝他们的孩子接触不适宜儿童的内容,但这种单标准评级系统能够适用于所有应用商店吗?

美国无线通信和互联网协会(CTIA)于3月末提出倡议,呼吁应用自愿进行自我认证。该计划正努力于今年年末施行,试图让应用开发商在产品中通过特定的评级和准则来定义内容。CTIA希望最终能够形成系统,让消费者更清晰地了解所使用手机设备上的应用。

这种提议让人想起音乐、电影和视频游戏的遭遇。无论好坏,应用已经成为一种娱乐形式,任何人都可以随时随地获取。经由过去数年的发展,该行业也成为庞大的业务,今年各商店总盈利预计达到38亿美元。

尽管如此,并非所有人都赞成CTIA的这个决定。在5月初递交给CTIA的函件中,权益组织ACT表示有3000名软件开发者成员的组织认为此倡议会扼杀人们开发应用的创意和兴致。

ACT主席Jonathan Zuck在递交给CTIA主席Steve Largent的信件中写道:“我们的成员向组织表达了自己的意见,拒绝与行业无关的人充当他们的监管人员。尽管CTIA的意图可能是正确的,但他们根本没有应用生态系统的相关经验或知识,而这些正是设定任何标准所需要的东西。开发商还表示进一步的担忧,称依靠其他可能带有竞争性的行业来设定市场标准,会打击应用编写人员的积极性。”

位于华盛顿的贸易组织CTIA代表的是无线行业的运营商、制造商和其他人员,其中包括许多运营手机应用商店的公司。(游戏邦注:苹果、Google、RIM、诺基亚和微软都是其成员。)

CTIA无线网络发展副主席David Diggs在电话采访中表示,应用评级系统的提案仍在评估中,提交的要求将向非CTIA成员公示。Diggs随后并未说明哪些公司参与应用评级提案的讨论。

依Diggs的说法,倡议原型来自于2009年联邦贸易委员会(FTC)发布的关于向儿童销售暴力产品的相关报告,组织在其中呼吁消费者应该知道更多他们正在下载的应用的信息。

Diggs说道:“在这份报告的内容中,FTC认为制定消费者所熟悉的内容分级系统可能会发挥作用。以此为指导思想,我们努力的方向是制定像MPAA为电影评级等消费者所熟悉的系统。”

但是这片领域的事态有些混乱,就手机应用中比例甚高的游戏而言,已经有特别成立的组织进行调节。

在美国,当20世纪90年代中期视频游戏行业面临政府监管时,娱乐软件评级委员会(ESRB)应运而生,对游戏业进行调整。组织要求发行商描述游戏中的内容并提供游戏片段,用于游戏评估。随后,参评游戏会获得某个分类的评级。游戏评级需要费用,费用多寡与游戏开发成本有关,这些资金用于维持整个评级系统。

ACT执行总监Morgan Reed说道:“CTIA进行评级与游戏评级不同,这种由游戏开发商赞助和管理的ESRB模式可能更受应用开发商青睐。ESRB的评级系统是真正的自我监管。”

由于应用数量的不断增长,在手机应用上使用类似的系统可能较为困难。就目前情况而言,应用发布的费用很低。尽管开发商可能耗费数万美元开发应用,但他们可以在苹果App Store等平台免费发布游戏,只要他们每年付给苹果99美元的开发费用即可。随后苹果可以从应用产生的销售、应用内购买和订阅中收取30%的费用。给这种方式添加额外的费用可能改变整个动态系统。

Reed建议如果最终出台的准则对本地应用有所限制,开发商可以将他们努力的方向转向Web。Reed说道:“如果评级系统由CTIA运行而且显得过于严格,开发商其实可以转向HTML5环境。如果游戏在网页上运行,那么系统可能就无法发挥作用。”

现有系统的做法

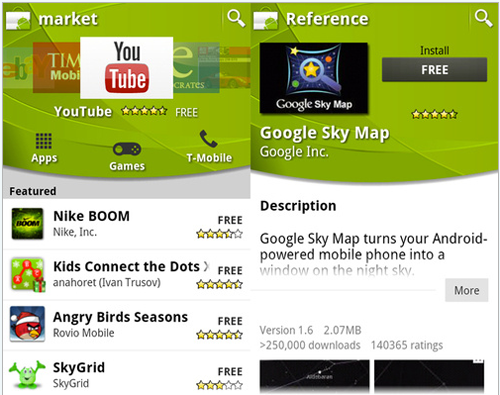

目前手机应用商店中已有各种内容控制措施,其中包括评级系统,这些可以告知消费者应用所包含的内容。现在来看看那些大型系统的做法:

尽管可能无法长期保持这种局面,但苹果是目前向用户提供最多应用的公司。苹果要求应用开发商给自己的内容评级,级别共分4种,从不包含任何不良内容的“4+级”到需要用户至少满17周岁的“17+”。为监督此类做法,苹果在审核过程中会查看应用的评级,而且公司有权将违规应用从App Store中撤出。苹果还提供限制iOS设备安装和运行应用的方法,即内置的家长控制系统。

Google也有类似的4级系统,范围从“所有人”直至“成年人”。开发商根据应用内容选择级别,随后才能将其发布至Android Market。如果用户举报某款已发布的应用与评级不符,那么Google会根据公司的准则重新定级并交由相关人员审核。Google会在开发商使用系统时让其浏览现有的级别并对应用进行评级。

RIM虽然没有对可使用应用的用户岁数做出特别规定,但他们有自己的内容准则,决定何种内容不得出现在应用中。

诺基亚要求提交至Ovi商店的应用遵从公司的内容准则。尽管没有以年龄为评定基础的系统,但有个“内容是否适宜大部分消费者”的机制。诺基亚确立了一系列不允许出现的内容,而且有公司代表告知CNET称诺基亚也会评估应用,确保其内容与用户年龄和文化相符。

微软也有应用需要遵从的内容原则。那些从其他平台导入且使用ESRB之类现有评级系统的游戏需要向微软提交此类信息,作为公司进驻Windows Phone Marketplace的认证的部分内容。这些信息会出现在应用的描述中。

面临的问题

需要对CTIA的倡议做出澄清的是,目前还没有做出任何决定,何种应用商店将参与评级也还未定下。基于这种情况,公司是否同意此类准则和评级方式还是个问题。就像苹果指出它不允许某些Google许可的东西出现在App Store中,反之亦然。这些准则使得商店各不相同,也是竞争的另一个筹码。

近期许多政府官员要求苹果、Google和RIM移除不合应用分级监测标准的应用,这种准则不一致性就此显露出来。RIM遵从这个要求,但苹果和Google并未采取行动。评级组织在遇到这种情况时能够做出裁定吗?

现有的监管这些商店的评级和审核过程如何处理也是个问题。如果新系统到位,是否就意味着有人需要重新审核应用,确保他们符合规定吗?最终决定由谁来做,新系统如何实行,谁提供相关费用,这些都是问题。

ACT的Reed表示关键之处在于找到方法去除误导用户的应用。他说道:“任何为开发商所采纳的监管系统都应该把自我监管排在前列,把惩罚措施放在后面。”(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,转载请注明来源:游戏邦)

App stores march toward shared ratings system

By Josh Lowensohn

The wireless industry’s trade group wants to put ratings on mobile apps to help parents keep inappropriate content out of their kids hands, but does a one-size ratings system fit all app stores?

The initiative, which was launched near the end of March by CTIA-The Wireless Association, calls for “voluntary self-certification of apps.” The program is on track to be in place by the end of this year and seeks to have app-makers define the content within their creations based on a specific set of ratings and guidelines. The end result is a system the CTIA hopes will give consumers a “more informed” choice when using applications on mobile devices.

The move is reminiscent to what’s happened to music, movies, and video games. Apps have–for better or worse–become a form of entertainment that can be had anywhere and by nearly anyone. They’ve also become big business in the last few years, with combined revenues from the various stores coming in at an estimated $3.8 billion this year.

Not everyone is happy with the putting the CTIA in the driver’s seat for decision making though. In a note to the CTIA earlier this week, advocacy group ACT said its 3,000-member association of software developers believed the initiative could stifle innovation and interest in app development.

“Our membership has expressed to us that they reject the idea of unrelated industries acting as their regulator,” ACT President Jonathan Zuck wrote in a letter addressed to CTIA President Steve Largent. “While CTIA’s intentions may be sound, they don’t have the experience or knowledge of the apps ecosystem that is essential for any standards-setting board. Developers are further concerned that relying on other industries, with potentially competing interests, to set marketplace standards is a nonstarter for app writers.”

The CTIA is a Washington, D.C.-based trade group that represents carriers, manufacturers and other players in the wireless industry, including many of the companies with mobile application stores. Apple, Google, Research In Motion, Nokia, and Microsoft are listed as members.

David Diggs, who is the CTIA’s vice president of wireless Internet development, said in a phone interview that the group is still in the middle of evaluating proposals for app ratings systems following half a dozen submissions that came in after its announcement; that call for submissions was made open to non-CTIA members. Diggs would not say which entities were in discussions about the app rating proposal.

Diggs said the genesis for the initiative came from a 2009 Federal Trade Commission report about marketing violent content to children, wherein the organization called for more information to be made available to consumers about the applications they were downloading.

“Among other things, the FTC thought that it would make sense to devise a content classification system that would be familiar to consumers,” Diggs said. “What we’re moving towards, and this was in the guidelines, is that it ought to relate to things consumers already understand like MPAA ratings for movies.”

But this is an area where things get murky. For something like games, which make up a healthy majority of mobile applications, there are already groups that exist specifically for the purpose of self-regulation.

In the U.S., there’s the Electronics Software Rating Board (ESRB), which was formed in the mid-1990s as a self-regulatory arm at a time when the video games industry faced regulation from the government. That group has publishers filling out a description of what types of content are in a game, as well as providing footage for a title’s evaluation. In return the game gets a ratings classification. All of this comes with a fee, which varies depending on the cost of the game’s development, and goes to support the ratings system’s existence.

“This points to the difference,” said Morgan Reed, ACT’s executive director. “If it’s a CTIA self-derived push, that seems like an intermediary regulator. A preferred model would be the ESRB, which is funded and managed by game developers. ESRB’s rating system is actual self-regulation.”

Using a similar system for mobile apps could prove to be difficult given that the volume of applications continues to grow. The app publishing landscape as it exists right now has a very low entry fee. While a developer may spend tens of thousands of dollars developing an application, they can publish it somewhere like Apple’s App Store free of charge as long as they’re paying Apple the $99-a-year developer fee. Apple then makes 30 percent on the sale, and from any in-app purchases, and subscriptions made within the app. Adding extra fees on top of that could change that dynamic.

Reed suggested that developers could also shift their efforts to the Web if the guidelines end up restricting what can be done with native apps. “If a ratings system were to be implemented by the CTIA and deemed too partisan, developers–especially of quick and dirty games–start really moving to an HTML5 environment,” Reed said. “Where do you enforce a system that you get to by a Web page?”

Existing systems

Mobile application stores already have numerous content controls in place, including ratings systems that can alert consumers to whatever content is contained within. Here’s a breakdown how each of the big ones do it:

Apple, which currently has the largest volume of applications of the providers (though it might not hold that crown for long), requires app developers to rate their own content in one of four ratings ranging from “4+” which contains no objectionable material, all the way to “17+”, which requires that users be at least 17 years old. To police this, application ratings are checked at the time of review by Apple, and the company has the power to pull them from the App Store. Apple also provides ways to limit what iOS devices are able to install and run using built-in parental controls.

Google has a similar four-tier rating system that uses an “everyone” to “high maturity” scale. Developers assign their application a rating based on its content, then publish it to the Android Market. If users flag a published application for somehow mis-rating itself, Google says it re-rates it per the company’s guidelines with a staff review. When deploying the system, Google had developers go through their existing catalogs and rate applications.

Research In Motion has its own set of content guidelines that determine what cannot be included in applications, though applications are not given a specific age group designation.

Nokia requires applications submitted to its Ovi store to comply with the company’s content guidelines. There’s no age-based system, instead it’s whether “content is appropriate for a wide spectrum of consumers.” Nokia maintains a list of items that aren’t allowed, and a company representative told CNET the company also evaluates apps to make sure content is “age appropriate and culturally sensitive.”

Microsoft has its own content guidelines apps need to conform to. Games that have been ported from platforms that use existing ratings systems such as the ESRB need to provide that information to Microsoft as part of the company’s Windows Phone Marketplace certification. This information is listed on application descriptions.

The bottom line

The thing to make clear about the CTIA’s initiative is that nothing has been decided yet, especially when it comes to which of the application stores will participate. Along with that, there’s the question of if those groups can agree upon a set of guidelines and ratings designations. As Apple has been happy to point out about its store, it does not allow things company like Google does, and vice versa. In many ways that gives these stores an identity, and adds another layer of competition.

Issues around these policy differences bubbled up recently when several government officials asked Apple, Google, and RIM to remove applications that alerted users to police checkpoints. RIM complied, while Apple and Google did not take action. Would the ratings body be given control to make judgments in such cases?

There’s also the question about what happens to existing ratings and the review processes that govern these stores. If a new system is put into place, does that mean someone needs to re-review applications to make sure they comply? And who makes that decision, how is it enforced, and who’s paying for that?

ACT’s Reed said that the key thing is making sure there’s a way to weed out apps that misrepresent what’s inside. “Any regulatory system adopted by developers needs to be one that is self-reporting on the front-end, and post-punishment on the other. There has to be some sort of mechanism for a bad actor who lies.” (Source: cnet)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号