开发者谈如何通过有效的规划让游戏核心更好玩

本文原作者:Thomas Grip 译者ciel chen

我想我们都会觉得有些游戏玩起来的感觉给人是有所不同的,总有那么些游戏玩起来让人感觉它们比其他游戏更像“游戏”——就比如说《超级玛丽》就比《亲爱的艾斯特(Dear Esther)》这类游戏更有游戏性。所以这是什么造成的呢?我想的答案是:规划性。

在游戏中,玩家越能做预先规划,游戏玩起就越让人投入。

在我用一些证据来证明我假设的正确性之前,我会先给出一些背景信息。要想明白为什么规划在游戏中占据如此显著的地位就得深入挖掘到我们人类的进化史,然后来回答这个问题:为什么鱼会这么蠢?

以下是普通鱼类看到的世界:

是的,它们只能看到眼前的1-2米处,而且有时候还看不到这么远。这意味着鱼是没法准备太多计划的,它只能等什么东西到了眼前它才会做出反应;这基本上就是他们一生的活法了。所以如果把鱼的生命比作游戏,那就好像在玩限制版本的《吉他英雄》,只能弹出一堆无规则的噪音。所以这也是为什么人们总能钓到鱼——鱼无法像人类一样思考,他们只能靠天生反应过活。

在我们地球的整个历史上,有很大一部分的时间里,生命就是以这样的形式存在的。但是在4亿多年前发生了些事——鱼开始向大陆迁移,突然之间他们的视野能看到更多了,像这样:

这让它们的世界都变了。突然之间它们可以做出提前一步的计划了,并且它们可以开始适当地对周围环境进行思考了。在这之前,聪明的头脑智识只是一种精力的浪费,而现在却成了了不起的本事。事实上,这个转变真的太重要了,甚至它可能是意识进化的一个关键因素。据我目前所知,Malcolm MacIver写过这样一个理论,内容是:

“大概3.5亿年前泥盆纪时代,像提塔利克鱼这类的动物开始首次尝试登陆陆地——这里从它们的感知的角度来看就是一个全新的世界。现在它们的视野清晰了,大概比之前清晰10000倍。所以,只要简单地把眼睛探出水面,我们的祖先的视野就从可怜的云里雾里变成了美好的万里晴空,在阳光明媚之下它们得以大范围大距离地阅遍这片土地。”

从进化的角度上来看,这使得第一批“好视野俱乐部”成员处在了一个非常有趣的位置。想想第一只发生任意突变的动物,它们的感官接收与行动输出有可能会因此发生脱节(在脱节发生之前,它们的快速联系是很重要的,因为它们需要做出反应来避免成为其他动物的午餐)。

在这个时候,它们能够潜在地探索各种各样的未来可能,然后选择其中最有可能走向成功未来的那条道路——举个例子,不要直冲冲地朝羚羊冲过去,这会冒着太快暴露自己位置的危险,你可以选择沿着一排灌木丛悄悄地潜行过去(小心你的“未来晚餐”,它们的视力比它们的水生祖先好1万倍)等你离得更近的时候再冲过去。”

为了展示上述场景,有以下图片示意:

这幅图很好地展示了登陆陆地前后所发生概念性的变化。在第一种条件下你只能用基础的直线线路追捕,并且你只能“走一步说一步”。另一种情况下你就可以侦查前方的地形,思考多种方案,然后根据可得出的数据选择其中一种最佳方案。

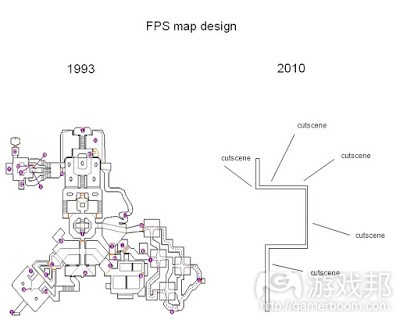

实际上的情况跟上述并不完全相符,不过却跟下面这幅比较了FPS老派设计与现代设计的图片有着惊人的相似:

我知道这并不是非常合适的比较,不过这里的重点在于当我们看这两幅图的时候,我们很清楚地就知道哪一幅能提供最好的游戏性。左边图所示的游戏远景更为复杂有趣的样子,而右边的所示的就是一副事件的线性排列。这就像是鱼眼中的世界与陆地动物眼中的世界对比,也就是意味着两种生物在规划能力有很大的差别。

还有其他跟观远与计划能力有关的有趣相关内容——Malcolm MacIver对关于章鱼智力问题的一个回答:

“令人不可思议的是,这种作为美味蛋白质不受保护的一团生物,会在经历了竞争激烈的捕食压力后在智慧方面追赶上人类。而且顺便告诉你们,它们的眼睛据我所知是最大的(最大的深海章鱼物种眼睛能有篮球那么大)。很显然,他们就是用这样的大眼睛来检测他们最大的天敌鲸鱼的轮廓以及海平面上的光亮的。

这个理论认为,计划的优势与你在反应时间内移动的位置成正比——它还确定了我们进化史上在这段关系中发生过巨大变化的一个时期——这个时期可能是让规划能力发展的关键。有趣的是,章鱼和古鱼在执行它们的动作之前往往是保持静止不动的。这极大地利用了他们相对较小的感觉中枢。换句话说,对于那些困在水雾中的动物来说也许还有其他方法去得到足够大的感觉中枢,以便于做好计划(这里所说的“感觉中枢的足够大”是相对于他们移动前往的空间来说的。)

视野肯定不是我们人类达现在的智力和感知水平的唯一因素。还有另外重要的因素是我们的直立姿态还有灵巧自由的双手——站立的姿势意味着我们可以看得更远并且解放了双手——我们主要就是通过它们来塑造我们周围世界的:我们用双手制造工具、改变环境以及优化生存条件。而这些所有的一切都与规划能力息息相关。一旦我们学会如何重塑周围世界,我们就有了非常多的选择性,而我们规划的复杂性也会极大程度地增加。

这还没完——规划也是我们社会生活中至关重要的一部分。心理学理论表明,我们模仿他人的能力既是我们形成规划能力的原料,也是规划能力生产出的产品。社会群体的道路上充满着对各种行动及其产生结果的仔细思考。

规划性还强调了另外两个现象,最近大家在博客上一直有着相关的热烈讨论:就是思维模式和存在。我们的思维模式之所以存在是因为我们能够在行动之前对行动进行评估,这对于规划性来说显然是非常关键的。而存在则是一种我们把自己融入到我们计划当中的一种现象。我们不止想模拟世界所发生的事情,还想模拟我们自己。

所以,总的来说:关于规划性为什么会成为我们人类的基础组成部分是有很多进化上的原因的。它是我们之所以为人的很大部分原因,而当我们能够去利用这些能力的时候,我们就一定能发现这个能力的魅力。

所以,这里背景信息已经非常全面了,不过到现在为止有什么真正的有效证据来证明计划性在游戏中的重要性的吗?有的——事实上,有很多!我们来回顾一下我发现的最重要的那些证据。

有一种测量玩家参与度的模型叫做PENS(玩家体验需求满足度)——这是经过严谨的科学研究制成的模型。这个模型用的是以下标准来评估玩家对游戏的看法。

掌控性。就是看一款游戏能从多大程度上满足我们在能力上的需求——这是一种掌控游戏的感觉。

自主性。玩家的自由度有多少?玩家能通过什么方式来表现这种自主性?

联系性。游戏能在多大程度上满足玩家对和其他玩家有所联系的需求?

经证明,根据以上标准来衡量一款游戏的表现情况,和简单地询问玩家游戏是否“好玩”比起来,是一种测量成功更好的指标(销量、热门对这款游戏的热议度有多高等等)。

还有更重要的是,上面三个标准中有两个跟规划性有直接关系——竞争性和自主性,这两个标准都需要大程度地依赖于玩家的规划能力。让我们来看看为什么是这样。

为了玩家在游戏中感到有竞争力,他们需要对游戏运作方式有一个深度的了解。当然了,有一些游戏只需要玩家做出条件反应就够了,但是这种游戏通常都很简单。在大多数的节奏游戏中都会存在一些规则,玩家只有通过学习和了解这些规则才能玩好这个游戏——其中一大块学习内容是去了解构成每个关卡的旋律。为什么?为了让你的键入最优化(不论你是用手还是用脚),让每次敲击都尽可能在节拍上。所有这些都可以归结为:对未来的预测能力。

你可以在大部分游戏中都看到这种能力——在《暗黑之魂》中,当你了解怪是如何攻击的、关卡是如何制定的以及你了解了自己的攻击原理的时候,你就能把游戏玩得更好。也就是说,了解一个世界的运作方式,以及得到预测未来的能力是取得掌控性的核心要素。当然了,你也需要提高一些运动技巧来执行要求的动作,不过这些执行动作的技巧通常都比了解这些动作的原理和执行时机来的重要。仅仅只是有能力预测是不够的,你还需要意识到自己要达到怎样的目标,然后用自己的预测能力来执行达到目标所要求的步骤。用另一句话来说就是:你要会规划。

自主性也同样高度依赖于计划能力。想象一个游戏,在这里你的自由度很高,但是你不知道游戏如何运作的。每个人都在不了解基础游戏知识的情况下开启了一个复杂的策略游戏,这样的游戏并不会吸引人。为了让自由更有意义,你需要对你该做的事有一定概念——要了解游戏的机制是如何运作的,知道哪些是你要使用的工具、你需要达到的目标是什么。如果你对这些没有了解,那么自由也就变得让人困惑而没有意义了。

所以为了能给人提供以自主意识,游戏不只需要提供一个庞大的可能性空间,还要教玩家这个世界的运转方式以及让玩家知道自己在其中扮演什么角色。玩家需要能够在脑海中模拟各种可能发生的行为,然后想出一系列可以用来达到特定目标的行为顺序。当你能做到这样,你就拥有了有价值的自由。这应该非常明显了——我又一次地在描述规划能力了。一个玩家无法规划的世界里是不存在什么自主性的。

如果游戏只包含一条线性的时间序列,那同样也没什么意思。为了让玩家能够制定规划,就应该设置多种选择。如果存在可能性的只有某一连串行为,那就是另外一种情况了——这是一个没有自由度、自主性也不被满足的典型例子。再强调一次,规划和自主性是有非常错综复杂的联系的。

也可以说联系性也是和规划性有关系的。正如先前所解释的那样,任何社交互动都严重依赖于我们的规划能力。然而,我认为联系性同规划性的关联度不如另外两者来的强烈。相反,让我们从不同的角度来看看证据。

游戏界有一个持续了蛮长一段时间的趋势——增加的额外“meta”特性,最常见的体现就是制造系统,这个特性以各种形式存在于大部分所有的大型游戏当中——还可见于类RPG的水准测量元素:针对的不只是角色,还有装备和武器。另外搜集一种货币来购买各种物品的趋势也很常见。你可以在最近发行的任意一款游戏身上找到这些趋势中的至少一种。

所以游戏中为什么会存在这些趋势?答案很简单:它们让游戏变得更好玩。一个比较难回答的问题是:为什么是这些趋势而不是其他趋势的呢?这时候答案不会只是因为它们让玩家有更多的事情可做,毕竟你也不会觉得一个包含各种各样迷你游戏的游戏有多好玩。反之我们倒是经常会看到某些具体类型的游戏特点被一次又一次地重复使用。

我的理论认为这一切都跟规划性有关。主要原因是这些特点的存在让玩家有更多的规划可能空间,以及更多可以融入到计划中的工具。例如,当搜集货币的行为与一家商店结合起来的时候就意味着玩家将有购买某件物件的目标。搜集一定数量的货币来进行商品交换的这种观点就是一种规划。如果这件欲购商品和货币搜集的方式都和核心游戏玩法循环有关联,那么该meta特点将会使这种核心游戏玩法循环玩起来让玩家更有规划感。

就是这些额外特点能让普通的游戏玩法变得有趣起来。你可以想想你在《最后生还者》中对在战斗中对所使用武器的思考——你有一些合成物品的碎片,这些物品可以让你在战斗中适用不同的战术,而由于你无法做出所有的物品,你就得做出选择,而这些做出的选择就是一种规划,这种时候游戏的浸入感就随之增加了。

无论你怎么看这种meta特点,有一点可以确认的是:他们是奏效的。因为如果它们没有什么卵用我们不会看到它们的趋势持续这么久了还在上升。当然了,要做出一款只有大量规划没有以上任何meta特点的游戏也是有可能的,不过这是很难的。对于游戏来说,拥有这些经过考验的特征是增加其游戏魅力的好渠道。即便如果你的游戏是因为没有具备这些特征而失去了竞争优势,这些特征也很容易就可以添加到游戏里的。

最后 我需要讨论一下到底是什么让我对规划性产生了思考。这要从我开始把《活体脑细胞/SOMA》和《失忆症:黑暗后裔Amnesia: The Dark Descent》做比较说起了。当我们在设计SOMA的时候,我们觉得尽可能多地增加有趣的特点非常重要,因为我们希望玩家能有很多不同的任务去完成。我觉得完全可以说SOMA在交互性和多样化方面的内容做的比Amnesia来的多。但是尽管如此,很多人抱怨SOMA更像是个步行类的模拟器游戏。而我却不记得Amnesia有过这种类似的评论。为什么会这样呢?

一开始我无法理解,但是之后我开始列出了这两款游戏的主要差异:

Amnesia有健全的系统

光/健康资源管理

任务谜题分散在各个枢纽地区

这些都跟玩家的规划能力有直接的联系——健全的系统意味着玩家需要思考他们要走的道路方向,他们是否应该看到怪兽等等。这些特点都是玩家在通关时需要考虑的事情,它们让玩家需要持续性地做出提前规划。

资源管理系统也是按照相似地方式运作的——玩家需要思考何时、以何种方法来使用他们手头上的资源。该系统还让玩家的考虑上了一个层次——玩家更清楚地知道地图上能找到哪些东西。当玩家进入一个房间,打开抽屉将不再只是一个无聊的活动,因为玩家知道这些抽屉中有的会放着一些有用的物件,那么地毯式搜索房间就成为了大计划中的一部分了。

在Amnesia中很多关卡设计都设有一个很大的难题要解决(比如说:启动一台电梯),而这个大难题又要通过一些列分散式的、通常有内在联系式的小谜题来解决。通过把谜题分散到房间各个角落,玩家需要不断地考虑接下来的一步。想通过简单的“确保我把每个房间都调查过一遍”的方法是不太可能通关游戏的。你需要的是思考房子的哪些地方是你需要返回查看的,还有哪些谜团是有待解决的。这并不会非常复杂,但是这足够玩家产生一种规划感了。

SOMA就一个这样的特征都没有,就是这些附属特征的缺失让它的规划性丢失,这意味着整个游戏让人感觉不好玩。一些玩家甚至会觉得这款游戏可以归入行走模拟器行列。如果当初我们就知道规划的重要性,我们是可以做点什么来弥补这个漏洞的。

一款依赖于标准核心玩法循环的“正常”游戏是没有这类问题的。计划能力是建立在经典的游戏运作方式的基础上的。当然了,这些知识可以让游戏做得更好,但这并不是必须的——这是我认为规划性作为游戏的基础方面被如此低估的原因。唯一一个具体的例子在我找到的一篇Doug Church写的文章有提到,上面说到:

“这些简单持续的掌控、配上可预测性较高的物理运动(具体指马里奥世界),这让玩家能够很好地对自己的尝试所产生结果进行猜测。怪物和环境在复杂程度上增加,但是新的和特殊元素是缓慢引入的,并且通常需要建立在现有的交互原则上的。这让游戏环境变得非常有辨识度,也就是说这会让玩家很好做出行动计划。如果玩家看到一个高平台,对面有一只怪物,或者水面下放着一个宝箱,他们会开始思考要如何接近它们。

这会让玩家投入到一个非常缜密的规划流程里。他们已经知道了(通常是无意识的)这个世界是如何运作的了,知道了要如何行动、如何与它交互,还知道什么是他们必须克服的障碍。然后,他们常常是下意识地会设计出一个计划来前往他们想要去的地方。在玩游戏的时候,玩家做了成千上万的计划,有的能行得通,有的行不通。关键在于当计划失败时,玩能明白为什么失败。这个世界的实时性很强,以至于所做规划一旦行不通你就知道是哪里出问题了。”

这篇文章真的非常有两点,它完美地表达了我想说的东西。这是一篇1999年的文章了,从那以后我再找不到什么其他的资料有对这篇文章进行过讨论,更别说对这个概念的扩展了。当然了,你可以说规划性可以归结为Sid Meier的“一些列有趣的选择”,但是那对我来说似乎太过于模糊了,这跟预测世界是如何运作以及之后根据其运作原理做规划的方面并没有太大的关系。

唯一一次出现类似讨论是在对浸入式Sim(模拟策略)类型游戏的探讨中。考虑到Doug Church对创建这类游戏有丰富经验,这并不是什么惊奇的事。例如,对于应激性游戏玩法来说,浸入式sims是尤其有名的,这种游戏玩法很大程度上依赖于玩家对游戏世界的认知程度和在该认知程度基础上做出的游戏规划。这种设计理念在近期发行的例如《羞辱2(Dishonored 2)》这样的游戏中可以很清晰看到。所以,很明显,游戏设计者会从这些方面来思考游戏的设计。但是对我来说不太明显的是——它被看做是让游戏有吸引力的一个基本内容,并且让人感觉更像是设计的子集。

正如我上面提到的那样,这大概是因为当你进入到“正常”游戏玩法中时,很多计划自然而然就浮现出来了。然而,这对叙述游戏来说却不是如此。事实上叙述式游戏经常被认为“不太像游戏的游戏”,因为它们没有像《超级玛丽》这类游戏里的普通的游戏玩法。因此,经常会有是喜欢操作类游戏多一点还是故事类游戏多一点的这类讨论,就好像这两种类型游戏之间水火不容一样。然而,我认为之所以存在这么大分歧的一个理由就是我们还没有弄清楚叙述性游戏的游戏性是如何运作的。就像我先前博客里有说到的那样,在设计上,我们困在了一个局部极大值上。

“规划是游戏基础内容”这个想法就解决了这个问题。与其说“叙述性游戏需要更好的游戏性”,我们可以这么说“叙述性游戏需要更多的规划性”。

为了比较好地理解我们需要在规划方面做的内容,我们得要有一些支持性的理论来解释这一切。我上礼拜提出的SSM框架就非常适合做这个角色了。

大家最好是去上周的博客文章看一下,里面可以读到完整的细节,不过为了文章完整性我得在这里概述一下内容框架。

我们可以把游戏分成3个不同的空间。首先,我们有系统空间。这是所有代码所在以及所有的模拟发生所在;系统空间主要是处理一切抽象符号和运算的。其次是我们有故事空间,这里为系统中所发生的事情提供上下文。在系统空间中,马里奥只是一组“碰撞边界”而已,但是随后,当这些抽象信息从故事空间走过一趟就变成了一名意大利水管工。最后,我们有心智模型空间,这是有关玩家对这款游戏的看法,以及对游戏世界里存在的一种心理复制。然而,由于玩家基本不太了解系统空间到底发生了什么(也不知道如何解读故事背景),所以这也只是个有根据的猜测。最后,心理模型还用于玩家的游戏过程以及决策过程里。

这样我们就可以开始定义游戏性是什么了。首先我们要聊聊关于行动的概念。行动基本上就是指玩家在玩游戏时的表现,它有以下几个步骤:

对系统空间和故事空间所接受到的信息进行评估。

根据手头的信息建立一个心智模型。

模拟执行某种行动所产生的结果。

如果结果还OK,就把合适的键入(比如按一个按钮)输入到游戏中

很多这样的行动都是在无意识的情况下发生的。从玩家的角度来看,他们大部分会把这些步骤看作“做了的事情”,并且对所发生的实际思维流程毫无意识。但是这确实是玩家在游戏中做出行动时所发生的一系列程序——这些行动可以是在《超级玛丽》里让马里奥在悬崖边上跳来跳去,也可以是在在《Sim City》里建一座房子。

既然我们明白了什么是行动,我们可以到下一步了——什么是游戏性。它其实就是把几个行动串在一起,不过有一点要注意的:你不用真的把键入发送到游戏中,你只要进行这样的联想就好了。所以这一连串行动是建立在心智模型空间当中的,接着对这些连串的行动进行估计预测,看看结果是否令人满意,只有满意我们才开始输入所需的键入。

换句话说:游戏性就是跟规划有关,然后执行规划内容。然后基于以上我所示的所有证据,我的假设是:你能串在一起的行动越多,游戏性感觉越好。

不过如果只是单纯地把随便几个行动串起来那可不能叫做规划。首先,玩家需要拥有某个他们要为之努力来达成的目标;然后这些行动都应该要有其意义之所在——这是简单地把一连串步行动作串在一起对玩家来说可一点吸引力也没有。还有必要指出的就是——规划性并不是唯一能让游戏变得有趣的因素。所有其他的设计思考并不会因为你专注于规划而一下子失去其功能的。

然而,是存在有一堆的设计原则跟规划是齐头并进的。例如,创造一个具有实时性的游戏世界是重中之重,因为如果不这样的话,玩家就没法形成一个规划。这就是隐形墙那么闹心的原因——它们严重地阻碍了我们对规划的创作和执行;同样地,当失败来得有点随机时我们会很心烦也就说得通了。为了让游戏变得好玩,我们得要在脑海中模拟出到底哪里出了错。就像Doug Church上面的引言中所述:当玩家失败的时候,他们要知道失败的原因是什么。

另外一个例子是有关冒险游戏的建议——你应该一次性给出多个任务题目。从规划方面来说,这是因为我们总想让玩家有富足的空间来计划,让他们有“我要先做这个任务然后做那个”的规划概念。除此之外,还有其他很多与规划有关的相似原则,所以尽管规划不是让游戏好玩的唯一因素,不过游戏中的很多事情却可以由规划衍生出来。

让我们来快速地看看一些实际游戏中存在的例子.

假设玩家要在这个场景里刺杀红色衣服的男人。这里玩家不会只是跳下去然后求老天保佑,他们会需要有一些行动前的计划。他们也许一开始会先等待,等到护卫离开,然后瞬移到杀害目标身后,悄然无声地完成刺杀,等完成这些动作后,再用同样的方式离开——这就是玩家在行动前脑海里的活动。他们在没有某些计划之前是不会行动的。

这个计划也许行不通,也许玩家的偷偷靠近会被那个男人发现然后发出声音警告。这样的话就破坏了计划,然而这不意味着玩家的计划是完全不正确的,这只能说明他们没能完成其中一个环节的动作。如果表现得好,玩家是可以成功的。同样地,玩家也许会错误地解读了心智模式或者错过了些什么——只要玩家能够以连贯的方式更新他们的心智模型,这也没太大关系。然后下次玩家就会试着去执行一个相似的计划,这时我们的玩家可以表现得更好。

这种制定计划的能力常常是最能让游戏变得好玩的因素。游戏通常一开始都有些无聊,因为一开始你的心智模式是有些支离破碎的,然后你的规划能力这时也不怎么样。不过在这之后,随着你越来越熟悉游戏,你的心智模式和规划能力都变好了,你能串起更多的系列行动了,因此游戏就变得更好玩了。这就是为什么游戏教程非常重要的原因——这些教程让玩家能更容易地积累经验,指导玩家正确地思考游戏的运作原理,从而尽早地脱离游戏初期的无聊感。

还有一点要注意的是,所做的规划不能过于简单,这样的话玩家所执行的行动会变得微不足道。所以规划至少要在某种程度上存在意义,这样游戏才能好玩。

规划不一定总要做成长期的,它也可以是非常短期的。可以看看《超级玛丽》的这个场景:

这里玩家需要在一瞬间做出一个计划。这里有一个需要注意的重点是,这里玩家不会只是盲目地做出反应。如果游戏能按照应有的原理运作,即使在一个压力大的情况下,玩家也能很快地制定出计划并努力地执行。

现在我们把这两个例子跟《亲爱的艾斯特(Dear Esther)》这类游戏做个比较:

我相信这个游戏有很多地方都是让人喜爱的,不过我也相信没人不同意这个游戏在游戏性上是做得不足的,然而到底缺了什么却很难有一个一致的答案。我听过很多人觉得是缺乏失败状态和竞争机制,不过我觉得这不太有说服力。你能猜到的——我觉得缺少的内容是规划性。

主要原因在于:人们觉得《Dear Esther》不好玩不是因为他们不会输,或者没有什么可以与之竞争对抗的对象;而是因为游戏没法让他们制定和执行计划——所以我们需要找到解决这点的方法。

通过从SSM框架的角度对规划性进行的思考,我们得到一个提示——有关什么类型的游戏性能构成“叙述类游戏玩法”:当你在心智模式空间里制定计划的时候,能通过从故事空间里得到的数据知道所需执行的行动是很重要。可以比较一下两个计划:

1)“首先我挑选出10件物品来增加角色X的信用度,这会让我该角色晋升为‘朋友关系’,然后X将会成我手下的一员,而这能让我获得10点的战斗奖励。”

2)“如果我帮助X清理她的房间,我就可以和他成为朋友。这样我之后就可以邀请她加入我们的旅行。她看起来就像个了不起的神枪手,我觉得跟她同行很安全。”

这是相当简单的例子,不过我希望我能说到点上。这两个例子描述的都是同一个计划,不过他们对数据有非常不同的解读方式。1号例子基本就处在抽象的系统空间里,而2号例子则多了一些叙述感,是基于故事空间的解读。如果能把游戏规划性跟第二个例子中制定的计划联系起来,就是说我们对合适的叙述了游戏玩法有了一定认识了——这是交互性叙述游戏艺术发展的关键一步。

我相信对规划的思考就是让交互性叙述游戏变得更好的关键一步。游戏设计依赖与“标准”游戏性中自然产生的规划性内容已经有太久太久了,不过当我们不再依赖的时候,我们就需要格外地小心了。明白规划性是游戏的一大驱动力是非常有必要性的一件事,所以我们就得确保我们在做叙述性游戏时要把规划性考虑在内。规划性绝不什么“银色子弹”(杀手锏),不过它确实是非常重要的游戏组成部分,我们在Frictional Games工作室做未来的游戏时,将会对规划性进行大量的思考。

本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao

I think we can all agree that there is a difference in how certain games feel to play. There are just certain games that feel “gamier” than others. Just compare playing Super Mario to something like Dear Esther, and I think it’s clear that the former feels like it has more gameplay than the latter. What is it that causes this? My hypothesis: the ability to plan.

The more a player can plan ahead in a game, the more engaging that game will feel to play.

Before I cover some evidence of why this is most likely true, I will need to get into some background information. In order to understand why planning has such a prominent role in games, we need to look into the evolution of our species and answer this question: why are fish so stupid?

This is how the world looks to the average fish:

They can really only see 1-2 meters in front of them and often it’s even worse than that. This means that a fish can’t do much planning. It just reacts to whatever pops up in front of its face; that’s really what their lives are all about. If a fish’s life was a game, it would be a limited version of Guitar Hero played to random noise. This is why fishing works. Fish don’t think like us, they’re mainly just driven by hardwired responses.

For a large part of earth’s history this was what life was like for organisms. But then 400 million or so years ago something happened. Fish started to move on to land. Suddenly, the view looked more like this:

This changed their world. Suddenly it was possible to plan ahead and to properly think about your environment. Previously, smart brains had been a waste of energy, but now it was a great asset. In fact, so important was this shift that it is probably a big factor in how consciousness evolved. Malcolm MacIver, who as far as I can tell originated this theory, writes about it like this:

“But then, about 350 million years ago in the Devonian Period, animals like Tiktaalik started making their first tentative forays onto land. From a perceptual point of view, it was a whole new world. You can see things, roughly speaking, 10,000 times better. So, just by the simple act of poking their eyes out of the water, our ancestors went from the mala vista of a fog to a buena vista of a clear day, where they could survey things out for quite a considerable distance.

This puts the first such members of the “buena vista sensing club” into a very interesting position, from an evolutionary perspective. Think of the first animal that gains whatever mutation it might take to disconnect sensory input from motor output (before this point, their rapid linkage was necessary because of the need for reactivity to avoid becoming lunch). At this point, they can potentially survey multiple possible futures and pick the one most likely to lead to success. For example, rather than go straight for the gazelle and risk disclosing your position too soon, you may choose to stalk slowly along a line of bushes (wary that your future dinner is also seeing 10,000 times better than its watery ancestors) until you are much closer.”

To showcase the above, he has the following image:

This images nicely shows the conceptual difference in the processes involved. In one you basically just use a linear process and “react as you go”. In the other one you scout the terrain ahead, consider various approaches and then pick one that seems, given the available data, to be the best one.

It is not exactly the same, but there is a striking likeness to the following image comparing old school and more modern FPS design:

I know that this is not a completely fair comparison, but the important point here is that when we look at these two images, it feels pretty clear which of these two designs ought to have the best gameplay. The image on the left represents a more complex and interesting landscape, while the one on the right represent a linear sequence of events. And just like the worlds of a fish compared to that of the world of land animals, this means a huge difference in our ability to plan.

There are other interesting connections with the ability to see far and to plan. Malcolm MacIver replies to a question regarding the intelligence of octopi:

“It’s incredible what being an unprotected blob of delicious protein will get you after eons of severe predation stress. They, by the way, have the largest eyes known (basketball size in the biggest deep sea species). Apparently, they use these to detect the very distant silhouettes of whales, their biggest threats, against the light of the surface.

The theory is committed to the idea that the advantage of planning will be proportional to the margin of where you sense relative to where you move in your reaction time. It then identifies one period in our evolutionary past when there was a massive change in this relationship, and suggests this might have been key to the development of this capacity. It’s interesting that octopuses and archerfish tend to be still before executing their actions. This maximally leverages their relatively small sensoria. There may be other ways, in other words, for animals trapped in the fog of water to get a big enough sensorium relative to where they are moving to help with planning.”

Sight is of course not the only reason for us humans to have evolved our current level of intelligence and consciousness. Other important factors are our upright pose and our versatile hands. Standing up meant that we could see further and allowed us to use our hands more easily. Our hands are the main means with which we shape the world around us. They allowed us to craft tools, and in various ways to change parts of the environment to optimize our survival. All of these things are deeply connected to the ability to plan. Once we learned how to reshape the world around us, our options opened up and the complexity of our plans increased immensely.

It doesn’t stop there. Planning is also a crucial part of our social life. Theory of mind, our ability to simulate other people, is both a reason for and a product of our planning abilities. Navigating our social groups has always been a careful activity of thinking about various paths of action and their consequences.

Planning also underlies two other phenomena that have been discussed recently on this blog: Mental Models and Presence. The reason why we have mental models is so that we can evaluate actions before we make them, which obviously is crucial to planning. Presence is a phenomenon that comes from us incorporating ourselves into our plans. We don’t just want to model what happens to the world, but also to ourselves.

So, to sum things up: there are lots of evolutionary reasons why planning would be a fundamental part of what makes us human. It’s a big part of who we are, and when we are able to make use of these abilities we are bound to find that engaging.

So this background is all very well, but is there really any good evidence that this is actually a thing in games? Yes – in fact, quite a bit of it! Let’s review the ones that I find the most important.

There is a model of player engagement called PENS (Player Experience of Need Satisfaction) which is quite rigorously researched. It uses the following criteria to evaluate what a player thinks about a game.

Competence. This is how well a game satisfies our need to feel competent – the sense of having mastered the game.

Autonomy. How much freedom does the player have and what options do they have to express it?

Relatedness. How well is the player’s desire to connect with other people satisfied?

Measuring how well a game performs on the above metrics has been shown to be a much better indicator of various types of success (sales, how likely people are to recommend the game, and so forth) than simply asking if the game is “fun”.

And, more importantly, two of the above factors are directly related to planning. Both Competence and Autonomy heavily rely on the player’s ability to plan. Let’s go over why this is so.

In order for a player to feel competent at a game they need to have a deep understanding of how the game works. Sure, there are games where mere reflexes are enough, but these are always very simplistic. Even in most rhythm games there are certain rules that the player needs to learn and understand in order to play well. A big part is also learning the melodies that make up each level. Why? In order to optimally place your inputs (be that fingers or feet) to hit as many beats as possible. All of these aspects boil down to one thing: being able to predict the future.

You see the same thing in most games. You get better at Dark Souls when you understand how monsters attack, how levels are laid out and how your own attacks work. Learning how a world operates and gaining the ability to predict is a cornerstone of competence. Sure, you also need to develop the motor skills to carry out the required actions, but this is almost always less important than understanding the whys and whens of the actions. Simply being able to predict is not enough, you also need to have a sense of what goal you are trying to achieve and then, using your predictive abilities, to carry out the steps required to reach it. Or in other words: you need to be able to plan.

Autonomy is also highly dependent on the ability to plan. Imagine a game where you have plenty of freedom, but have no idea how the game works. Everybody who has booted up a complex strategy game without understanding the basics knows that this is not very engaging. In order for the freedom to mean something, you need to have an idea what to do with it. You need to understand how the game’s mechanics behave, what tools are at your disposal, and what goals you want to achieve. Without this, freedom is confusing and pointless.

So in order to provide a sense of autonomy a game needs to not only provide a large possibility space, but also teach the player how the world works and what the player’s role in it is. The player needs to be able to mentally simulate various actions that can take place, and then come up with sequences that can be used to attain a specific goal. When you have this, you have freedom that is worth having. It should be pretty obvious that I am again describing the ability to plan. A world in which the player is not able to plan is also one with little autonomy.

Similarly, if the game only features a linear sequence of events, there’s not much planning to be done. In order for the player to be able to craft plans there need to be options. This is not the case if only a certain chain of actions is possible. This scenario is a typical example of having no freedom, and unsatisfactory in terms of autonomy. Again, planning and autonomy are intricately linked.

One could make the case that Relatedness also has a connection with planning. As explained earlier, any social interactions heavily rely on our ability to plan. However, I don’t think this is strong enough and the other two aspects are more than enough. Instead let’s look at evidence from a different angle.

One trend that has been going on for a long time in games is the addition of extra “meta” features. A very common one right now is crafting, and almost all big games have it in some way or another. It’s also common to have RPG-like levelling elements, not just for characters, but for assets and guns as well. Collecting a currency that can then be used to buy a variety of items also turns up a lot. Take a look at just about any recent release and you are bound to find at least one of these.

So why do games have them? The answer to that is quite easy: it makes the game more engaging. The harder question is why that should be the case. It can’t solely be because it gives the player more to do. If that was the case you would see games adding a random variety of mini games to spice things up. But instead we are seeing certain very specific types of features being used over and over again.

My theory for this is that it’s all to do with planning. The main reason that these features are there is because it gives the player a larger possibility space of plans, and more tools to incorporate into their planning. For instance, the act of collecting currency combined with a shop means that the player will have the goal of buying a particular item. Collecting a certain amount of currency with a view to exchange it for goods is a plan. If the desired item and the method in which the coins are collected are both connected to the core gameplay loop, then this meta feature will make the core loop feel like it has more planning that it actually has.

These extra features can also spice up the normal gameplay. Just consider how you need to think about what weapons to use in combat during The Last of Us. You have some scrap you can craft items from, and all of those items will allow you to use different tactics during combat. And because you cannot make all of them, you have to make a choice. Making this choice is making a plan, and the game’s sense of engagement is increased.

Whatever your views on this sort of meta-feature are, one thing is certain: they work. Because if they weren’t we wouldn’t be seeing this rise in them persist over such a long time. Sure, it’s possible to make a game with a ton of planning without any of these features. But that’s the hard way. Having these features is a well-tested way to increasing engagement, and thus something that is very tempting to add, especially when you lose a competitive advantage by not doing so.

Finally, I need to discuss what brought me into thinking about planning at all. It was when I started to compare SOMA to Amnesia: The Dark Descent. When designing SOMA it was really important for us to have as many interesting features as possible, and we wanted the player to have a lot of different things to do. I think it is safe to say that SOMA has a wider range of interactions and more variety than what Amnesia: The Dark Descent had. But despite this, a lot of people complained that SOMA was too much of a walking simulator. I can’t recall a single similar comment about Amnesia. Why was this so?

At first I couldn’t really understand it, but then I started to outline the major differences between the games:

Amnesia’s sanity system

The light/health resource management.

Puzzles spread across hubs.

All of these things are directly connected with the player’s ability to plan. The sanity system means the player needs to think about what paths they take, whether they should look at monsters, and so forth. These are things the player needs to account for when they move through a level, and provide a constant need to plan ahead.

The resource management system works in a similar fashion, as players need to think about when and how they use the resources they have available. It also adds another layer as it makes it more clear to the player what sort of items they will find around a map. When the player walks into a room and pulls out drawers this is not just an idle activity. The player knows that some of these drawers will contain useful items and looting a room becomes part of a larger plan.

In Amnesia a lot of the level design worked by having a large puzzle (e.g. starting an elevator) that was solved by completing a set of spread out and often interconnected puzzles. By spreading the puzzles across the rooms, the player needs to always consider where to go next. It’s not possible to just go with a simple “make sure I visit all locations” algorithm to progress through the game. Instead you need to think about what parts of the hub-structure you need to go back to, and what puzzles there are left to solve. This wasn’t very complicated, but it was enough to provide a sense of planning.

SOMA has none of these features, and none of its additional features make up for the loss of planning. This meant that the game overall has this sense of having less gameplay, and for some players this meant the game slipped into walking simulator territory. Had we known about the importance of the ability to plan, we could have done something to fix this.

A “normal” game that relies on a standard core gameplay loop doesn’t have this sort of problem. The ability to plan is built into the way that classical gameplay works. Sure, this knowledge can be used to make such games better, but it’s by no means imperative. I think this is a reason why planning as a foundational aspects of games is so undervalued. The only concrete example that I have found[1] is this article by Doug Church where he explains it like this:

“These simple, consistent controls, coupled with the very predictable physics (accurate for a Mario world), allow players to make good guesses about what will happen should they try something. Monsters and environments increase in complexity, but new and special elements are introduced slowly and usually build on an existing interaction principle. This makes game situations very discernable — it’s easy for the players to plan for action. If players see a high ledge, a monster across the way, or a chest under water, they can start thinking about how they want to approach it.

This allows players to engage in a pretty sophisticated planning process. They have been presented (usually implicitly) with knowledge of how the world works, how they can move and interact with it, and what obstacle they must overcome. Then, often subconsciously, they evolve a plan for getting to where they want to go. While playing, players make thousands of these little plans, some of which work and some of which don’t. The key is that when the plan doesn’t succeed, players understand why. The world is so consistent that it’s immediately obvious why a plan didn’t work. ”

This is really spot on, an excellent description of what I am talking about. This is an article from 1999 and have had trouble finding any other source that discuss it, let alone expands upon the concept since then. Sure, you could say that planning is summed up in Sid Meier’s “A series of interesting choices”, but that seems to me too fuzzy to me. It is not really about the aspect of predicting how a world operates and then making plans based on that.

The only time when it does sort of come up is when discussing the Immersive Sim genre. This is perhaps not a big surprise given that Doug Church had a huge part in establishing the genre. For instance, emergent gameplay, which immersive sims are especially famous for, relies heavily on being able to understand the world and then making plans based on that. This sort of design ethos can be clearly seen in recent games such as Dishonored 2, for instance [2]. So it’s pretty clear that game designers think in these terms. But it’s a lot less clear to me that it is viewed as a fundamental part of what makes games engaging and it feels like it is more treated like a subset of design.

As I mentioned above this is probably because when you take part in “normal” gameplay, a lot of planning comes automatically. However, this isn’t the case with narrative games. In fact, narrative games are often considered “lesser games” in the regard that they don’t feature as much normal gameplay as something like Super Mario. Because of this, it’s very common to discuss games in terms of whether you like them to be story-heavy or gameplay-heavy, as if either has to necessarily exclude the other. However, I think a reason there is still such a big discrepancy is because we haven’t properly figured out how gameplay in narrative games work. As I talked about in an earlier blog post, design-wise, we are stuck at a local maxima.

The idea that planning is fundamental to games presents a solution to this problem. Instead of saying “narrative games need better gameplay”, we can say that “narrative games need more planning”.

In order to properly understand what we need to do with planning, we need to have some sort of supportive theory to makes sense of it all. The SSM Framework that I presented last week fits nicely into that role.

It is really best to read up on last week’s blog post to get the full details, but for the sake of completeness I shall summarise the framework here.

We can divide a game into three different spaces. First of all we have System space. This where all the code is and where all the simulations happen. The System space deals with everything as abstract symbols and algorithms. Secondly we have the Story space which provides context for the the things that happen in the System space. In System space Mario is just a set of collision boundaries, but then when that abstract information is run through the Story space that turns into an Italian plumber. Lastly, we have the Mental Model space. This is how the player thinks about the game and is a sort of mental replica of all that exists in the game world. However, since the player mostly never understands exactly what goes on System space (nor how to properly interpret the story context), this is just an educated guess. In the end though, the Mental Model is what the player uses in order to play the game and what they base their decisions on.

Given this we can now start to define what gameplay is. First of all we need to talk about the concept of an action. An action is basically whatever the player performs when they are playing the game and it has the following steps:

Evaluate the information received from the System and Story space.

Form a Mental Model based on the information at hand.

Simulate the consequences of performing a particular action.

If the consequences seem okay, send the appropriate input (e.g. pushing a button) to the game.

A lot of this happens unconsciously. From the player’s point of view they will mostly view this sequence as “doing something” and are unaware of the actual thought process that takes place. But really, this always happens when the player does something in a game, be that jumping over a chasm in Super Mario or placing a house in Sim City.

Now that we understand what an action is, we can move on to gameplay. This is all about stringing several actions together, but with one caveat: you don’t actually send the input to the game, you just imagine doing so. So this string of actions are built together in mental model space, evaluating them and then if the results feel satisfactory, only then do we start to send the required input.

Put in other words: gameplay is all about planning and then executing that plan. And based upon all of the evidence that I showed above, my hypothesis is: the more actions you can string together, the better the gameplay feels.

It isn’t enough to simply string together any actions and call that a plan. First of all, the player needs to have an idea of some sort of goal they are trying to achieve. The actions also need be non-trivial. Simply having a bunch of walking actions strung together will not be very engaging to the player. It’s also worth pointing out that planning is by no means the only thing that makes a game engaging. All other design thinking doesn’t suddenly go out the window just because you focus on planning.

However, there are a bunch of design principles that go hand in hand with planning. For instance, to have a consistent world is crucial, because otherwise it isn’t possible for the player to form a plan. This is why invisible walls are so annoying; they seriously impede our ability to create and execute plans. It also explains why it’s so annoying when failure seems random. For gameplay to feel good, we need to be able to mentally simulate exactly what went wrong. Like Doug Church expressed in a quote above: when a player fails they always need to know why.

Another example is the adventure game advice that you should always have several puzzles going at once. In planning terms this is because we always want to make sure the player has ample room to plan, “I will first solve this and then that”. There are lots of other similar principles that have to do with planning. So while planning is not the only thing that makes a game engaging, a great number of things that do can be derived from it

Let’s quickly look at some examples from actual games

Say that the player wants to assassinate the guy in red in this situation. What the player does not do is simply jump down and hope for the best. They need to have some sort of plan before going on. They might first wait for the guard to leave, teleport behind the victim, and then sneak up and stab them. When that’s done they leave the same way they came. This is something the player works out in their head before doing anything. It isn’t until they have some sort of plan that they start acting.

This plan might not work, the player might fail to sneak up on the guy and then he sound an alarm. In this case the plan breaks, however that doesn’t mean that the player’s plan was totally untrue. It just meant they didn’t manage to pull off one of the actions of. If presented properly, players are okay with this. In the same way, the player might have misinterpreted their mental model or missed something. This is also okay as long as the player can update their mental model in a coherent fashion. And next time the player tries to execute a similar plan they will get better at it.

Often this ability to carry out your plans is what makes the game the most engaging. Usually a game starts out a bit dull, as your mental models are a bit broken and the ability to plan not very good. But then, as you play, this gets better and you start stringing together longer sets of actions and therefore having more fun. This is why tutorials can be so important. They are a great place to get away from that initial dullness by making the experience a bit simpler and guiding the player to think in the correct manner about how the game works.

It’s also worth noting that plans should never be too simple to carry out. Then the actions become trivial. There needs to be a certain degree of non-triviality for engagement to remain.

Planning doesn’t always need to happen in the long term, it can also be very short term. Take this scene from Super Mario, for instance:

Here the player needs to make a plan in a split second. The important thing to notice here is that the player doesn’t simply react blindly. Even in a stressful situation, if the game works as it should, the player quickly formulates a plan and then tries to carry out that plan.

Now compare these two examples to a game like Dear Esther:

There are a lot of things one can like about this game, but I think everybody agrees that the gameplay is lacking. What’s harder to agree on, though, is what’s missing. I’ve heard a lot about the lack of fail states and competitive mechanics, but I don’t find these convincing. As you might guess, I think the missing ingredient is planning.

The main reason that people find Dear Esther unengaging is not because they cannot fail, or because there is nothing to compete against. It’s because the game doesn’t allow them to form and execute plans. We need to figure out ways of fixing this.

By thinking about the planning in terms of the SSM-framework we get a hint at what sort of gameplay that can constitute “narrative play”: When you form a plan in Mental Model space it is important that the actions are mostly grounded in the data received from Story space. Compare the the following two plans:

1) “First I pick up 10 items to increase the character X’s trust meter, this will allow me to reach the ‘friendship’-threshold and X will now be part of my crew. This awards me 10 points in range combat bonus.”

2) “If I help out X with cleaning her room, I might be able to be friends with her. This would be great as I could then ask her to join us on our journey. She seems like a great sharpshooter and I would feel much safer with her onboard.”

This is a fairly simplistic example, but I hope I get the point across. Both of these describe the same plan, but they have vastly different in how the data is interpreted. Number 1 is just all abstract system-space, and the number 2 has a more narrative feel, and is grounded in the story space. When the gameplay is about making plans like the second example, that is when we start to get something that feels like proper narrative play. This is a crucial step in evolving the art of interactive storytelling.

I believe thinking about planning is a crucial step in order to get better narrative games. For too long, game design has relied on the planning component arising naturally out of ‘standard’ gameplay, but when we no longer have that we need to take extra care. It’s imperative to understand that it drives gameplay, and therefore that we need to make sure our narrative experiences include this. Planning is by no means a silver bullet, but it’s a really important ingredient. It’s certainly something that we’re putting a lot of thought into when making our future titles here at Frictional Games.(source:gamasutra.com)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号