帮助你创造更吸引人游戏体验的3个问题

作者:Felipe Lara

如何让你的游戏变得更加吸引人?简单地说,你可以加强不同级别的游戏体验并将其与你的最终目标(游戏邦注:即盈利,教授或改变行为)联系起来。存在三个问题能够帮助你明确如何做好这点并且它们不仅适用于游戏,同时也适用于教育,VR体验以及其它需要吸引用户的软件。让我们进行更深入的说明。

我曾在之前的文章中讨论过成功的游戏和体验迫切需要突显自己让目标玩家注意到自己,随后才能在情感层面与玩家联系在一起让他们愿意花几分钟时间关注于游戏,并更长时间地投入于游戏中,最终愿意邀请朋友一起加入游戏。而为了做到这点,游戏就必须使用各种不同元素,如吸引人的图像,有趣的游戏机制,能让人产生共鸣的主题等等。像图像等元素能更好地突显游戏,而像机制等元素则更能提高游戏的用户粘性。不过这里的挑战便在于如何将这些元素正和在一起让玩家愿意长期保持用户粘性。

游戏设计是一项需要花几年时间去精通的艺术,所以我并不想过度简化用户粘性的艺术性,不过我发现以下三个问题能够带给你们有关创造出能够成功实现我们想实现的目标的游戏的有效线索。

问题1:你是否拥有一个吸引人的核心循环?

所有游戏都拥有一组能够让玩家不断重复而在游戏中前进的核心活动。这些重复的核心活动通常便是我们所谓的循环。明确你的游戏中拥有怎样的核心循环并分析它能够帮助你找出游戏可行与不可行的原因。

像《部落战争》等游戏便通过完善核心循环去吸引玩家长期沉浸于游戏中。从根本上来看循环其实非常简单:

玩家将完成能够迫使自己再次回到游戏中的奖励性活动并执行更多奖励性活动。游戏设计师兼初创企业顾问Amy Jo Kim便明确了核心循环在推动用户粘性所需要遵循的3个规则:

1.它们拥有一组吸引人的活动。在《部落战争》中,这些活动都与创建你的村庄并与其它村庄战斗有关。

2.这些活动将提供给你完成活动的更让人满足的正面反馈。这一反馈会让你觉得自己将更擅长做某事并从中获得了奖励。在《部落战争》中随着你的村庄的发展以及你战胜其它村庄,你将能够获得更多资源于更厉害的军队。

3.进入这样的循环中你将获得继续回到游戏中的动力。在《部落战争》中,所有的创建,资源收集和军队训练都需要花费时间,所以游戏中存在吸引玩家不断回到游戏中去收集自己想要的好处的动力。同时,当你投入更多时间去开发并定制自己的村庄且完善军队时,你便会觉得自己融入游戏体验中,并会愿意再次回到这里。

我觉得她的分析非常有用且能够提供一些有帮助的子问题去明确你的核心活动循环所存在的潜在问题与机遇:

1.你的核心循环中的活动是否足够吸引人?你该如何做才能让它们更吸引人?

2.你是否提供给玩家足够关于他们所完成的活动的正面反馈?他们是否觉得自己在不断前进且精通一种全新技能?你该如何增加正面反馈?

3.你的循环是否拥有能够将玩家带回游戏中的动力?随着玩家经历循环,他们是否觉得更深入于游戏中?你是否能够添加一些内容去吸引玩家回来?你是否能添加一些内容让玩家更深入其中?

问题2:你的核心循环是否与你的目标紧密联系着?

将你的核心活动循环与目标紧密联系在一起是创造一款成功游戏的关键。有许多免费游戏未能出售足够的道具,也有许多教育类游戏也不能有效教授玩家。有些游戏甚至使用来自其它成功游戏的经过认证的有趣的机制,但是他们却不能有效将这些机制与自己的目标结合在一起。

如果你想要去销售道具,你就必须确保这些道具能够强化你的核心循环体验。《Pokemon Go》便是一个成功案例。在《Pokemon Go》中玩家最初的核心循环主要有三个:1)四处游荡去寻找Pokemon,2)通过丢出Pokeball去抓住你所找到的Pokemon,3)前往PokeStop去获取更多PokeBall以及其它能够帮助你更轻松抓住Pokemon的道具。一开始你拥有足够的PokeBall并能够轻松抓住Pokemon,但随着你不断升级你将会发现更难捕抓Pokemon了,因为你需要更多PokeBall才能抓住他们,所以你也将很容易用掉自己的PokeBall。你可以不断前往PokeStop并获取更多PokeBall,而因为你已经在此有所付出,所以花1美元去获取额外的PokebalBall对你来说便不是什么严重的事。你可以通过不断前往不同PokeStop而继续免费游戏,但如果你愿意花费1美元你便能够更轻松地游戏并更快提高自己抓到稀有Pokemon的机会。你可以通过购买道具让自己的核心循环变得更加简单,所以即使游戏未强迫玩家去购买什么东西,很多人最终也会在此花钱去完善自己的游戏体验。

在教育类游戏中,这种核心活动应该能够带给人们可学习的内容。在《为什么游戏不能教授》的文章中Ruth Colvin Clarke分享了一些游戏活动与教育目标未能有效结合在一起的例子,这也让游戏失去了功效。她列举了一些实验证据去总结叙述类教育游戏导致糟糕的学习并比只是呈现教学内容的游戏需要花费更长时间。她所测试的其中一款游戏名为《Cache 17》,这是一款致力于教授玩家如何使用电磁器件的冒险游戏。但是这款游戏以及她在研究中提到的其它游戏所存在的问题是游戏的核心循环与它们想要传达的主题未能有效联系在一起。在《Cache 17》中,玩家需要解决一个有关在二战期间丢失的画的谜题,即需要去搜索地底碉堡。而这与主题的联系便是玩家偶尔需要创造一个机电装置去开门并在地堡中跳跃。游戏的核心循环是关于探索地堡并寻找线索,但却不是试验电磁设备。所以浏览关于电磁原理的幻灯片比玩这款游戏并获得学习更快速也更加有效。

如果教育目标可以和核心循环有效整合在一起,结果便会大不相同。让我们使用像Sid Meier的《文明》这样的资源测量游戏为例,即这是作为教授军人,技术,政治和社会经济发展之间关系的一种支持工具,该游戏纯粹的教育版本将在2017年正式公开。在这里,游戏的核心循环便是与其教育目标紧密联系在一起。即核心游戏便是关于明确经济发展,探索,政府,外交以及军事战斗间的有效结合去创造出一个真正成功的文明。

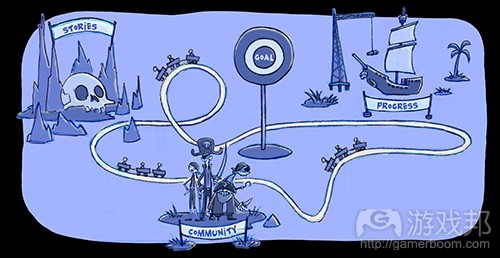

问题3:你的核心循环是否与吸引人的体验的所有元素相联系

就像我在之前文章所提到的,用户粘性的组合元素不只是关于游戏机制;它们还包括像图像,主题,故事和社区创建等其它东西。当你能够将游戏循环与其它用户粘性元素联系在一起时,它们的威力将更加强大。

让我们以《卡通城OL》为例,这是一款由迪士尼开发的游戏,游戏的主要目标是在入侵的商业机器人手中守护一个卡通世界—-我们想要确保游戏的核心循环能够增强整体的游戏主题。这一主题就像:“工作总是想要占据我们的游戏时间,但游戏却是最盛行的活动。”,所以我们将包含核心循环的根本内容去阻止机器人的入侵。如果没有街机一般的迷你游戏,你便不能获得雷根糖—-也就是你用于购买帮助自己阻止商业机器人入侵的道具所使用的货币。当游戏故事和主要冲突是关于守护Toontown并与商业机器人战斗时,如果没有了自由的乐趣你便不可能做到这点。结果便是核心游戏循环能够增强游戏主题以及工作与游戏间的冲突,因为主题将让许多玩家产生共鸣,除了那些6至12岁的最初目标玩家外,所以最终这款游戏能够获得许多玩家的喜欢。同时随着你去重复循环,游戏将推动你去探索其它游戏部分,与其他玩家组队交朋友,并开启一些新故事。换句话说它将推动你去发现一些新图像和故事,创建社区,精通机制,让这款游戏变得更加吸引人。结果便是这款游戏的平均玩家生命周期比当时大多数其它家庭类游戏都更长,并让这款游戏能在发行10多年后继续保持盈利。

如果你能够更多地将活动的核心循环与游戏用户粘性元素整合在一起,你将创造出一款更强大且拥有更强用户粘性的游戏。

结论

明确你的核心活动循环是什么能够帮助你创造出更有吸引力的游戏或体验。一旦你明确了循环,以下三个问题将提供给你创造出吸引人且成功的游戏:

1.你的循环中的活动是否足够吸引人?当玩家完成活动时你是否能够提供给他们足够的正面反馈。当玩家完成一个循环时他们是否能够获得让自己愿意更深入于游戏中的内容?

2.循环是否能够与你的目标直接联系在一起?如果你是在销售某物,那么循环是否能带给人们满足感?如果你是要教授某些内容,核心循环是否能与玩家需要学习的主题直接联系在一起?

3.你的循环是否能够强化一个吸引人的体验的不同元素?随着玩家经历循环,你是否能提供给他们更多可发现并让他们着迷的东西?你能否添加更有趣的故事元素?你能否引导玩家去组建一个更强大的社区?

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转发,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

3 Questions That Will Help You Make a More Engaging Experience

by Felipe Lara

How can you make your game more engaging and effective? In a nutshell, by making engagement stronger at the different levels of the experience and by making engagement connect to your ultimate goals: monetizing, teaching, or changing behavior. There are 3 questions that can help you figure out how to best do that and they can be applied not only to games, but also to education, VR experiences, and other software that needs to engage users. Let me elaborate.

I talked in a previous article how successful games and experiences need to first stand out so your target players notice you, then connect with them at an emotional level so they are willing to give you a few minutes of attention, then engage them so you can keep them for longer time, and finally get them to help you grow by sticking around and inviting their friends to join in (more about this process in this article here). To do that, games can use different ingredients like compelling art, fun game mechanics, resonating themes, etc. Some ingredients like art are better at helping you stand out, some others like mechanics are better at keeping engagement going (more about the ingredients in this article here). The challenge is how to mix and tie these ingredients together to take players to full-long-term engagement.

Game design is an art and a craft that can take years to master, so I don’t want to oversimplify the art of engagement, however I find that the following 3 questions can often bring good clues about what is missing and possible solutions to make the game more successful at reaching the goals we want.

Question 1: Do You Have a Compelling Core Loop?

All games have a core set of activities that the player repeats over and over to advance through the game. These core repeatable activities are usually called Loops. Clarifying what is the core loop in your game and analyzing it can be very enlightening in finding out why your game works or doesn’t work.

Games like Clash of Clans have perfected the use of loops to keep players engaged for a long time. At a basic level the loop is pretty simple:

You complete rewarding activities that compel you to come back and do more rewarding activities. Game designer and start-up consultant Amy Jo Kim identifies 3 rules that core loops need to follow to drive re-engagement:

1.They have a set of compelling activities. In Clash of Clans these activities are all related to building up your village and battling other villages.

2.Those activities give you positive feedback that make the completion of activities much more satisfying. This feedback makes you feel that you are getting better at something and getting rewarded for it. In Clash of Clans, as your village grows and as you defeat other villages you get access to more resources and better troops.

3.Built into this cycle there are triggers and incentives to keep you going back to the game. In Clash of Clans all the building up, collecting resources, and troop training takes time, so there is an incentive to keep coming back to reap the benefits of what you have already done. Also, as you put more time into developing and customizing your village and improving your troops, you feel more invested in the experience, which makes you want to go back again.

I think her analysis is very useful and provides useful sub-questions to identify potential problems and opportunities with your core activity loop:

1.Are the activities in your core loop compelling enough? How can you make them more compelling?

2.Are you giving your players enough positive feedback about the activities they completed? Do they feel they are progressing and mastering a new skill? How can you amplify that positive feedback?

3.Does your loop have triggers that pull players back into the game? As they go through the loop, do players feel more invested in the game? Can something be added to lure players back? Can something be added to make players feel more invested?

If you want to go a little deeper on how these 3 rules work in different loops, take a look Amy Jo Kim’s article here.

Question 2: Is Your Core Loop Tightly Connected to Your Goals?

Connecting your core activity loop tightly to your goals is key to making a successful game. There are many for profit free-to-play games that don’t sell enough items to even be sustainable, and many educational games that are not very good at teaching what they were suppose to teach. Some are even fun, using proven fun mechanics copied from other successful games, but unsuccessful at connecting those mechanics to their goals in any meaningful way.

If you are trying to sell items, those items should enhance your core loop experience. A successful example of connecting your loop to your goals is Pokemon Go. In Pokemon Go your beginner core activities are basically three: 1) walking around searching for Pokemon; 2) catching the Pokemon you find by throwing PokeBalls at them; and 3) walking to PokeStops to get more PokeBalls and other items that will make it easier to catch Pokemons. At first you have enough PokeBalls and catching Pokemons is very easy, but as you level up you will find higher level and harder to catch Pokemons that will need many more PokeBalls to be catched, so you will easily run out of PokeBalls. You can always walk to a PokeStop and get more PokeBalls, but since you are already somewhat invested, spending $1 to get extra PokeBalls doesn’t sound bad. You could keep playing for free by continue walking around to different PokeStops, but by spending $1 here and there you can make your play much more convenient and increase your chances of catching rare Pokemon faster. The items that you can buy directly make your core loop easier, so even if the game does not force you to buy anything, many players end up spending a few dollars here and there to improve their experience.

In the case of an educational game, that set of core activities should produce learning. In her article Why Games Don’t Teach, Ruth Colvin Clarke talks about some examples where the game activities do not align with the educational objectives, which makes the games very ineffective. She presents some experimental evidence that concludes that narrative educational games lead to poorer learning and take longer to complete than simply displaying the lesson contents in a slide presentation. One of the games she tested is a game called Cache 17, an adventure game designed to teach how electromagnetic devices work. The problem with this game and the other games she mentions in her study is that the games’ core loops are only vaguely related to the topics they are supposed to teach. In the case of Cache 17, the players need to solve a mystery about some missing paintings that disappeared during World War II by searching through an underground bunker. The link to the topic is that players occasionally need to build an electromechanical device to open some doors and vaults in the bunker. The core loop is about exploring a bunker and finding clues, not about experimenting with electromechanical devices. Not surprisingly, the study found that reading a slide about electromagnetic principles was quicker and much more effective at teaching the topic than playing the game.

When the educational objectives are more aligned to the core loop the results are very different. Using a resource strategy game like Sid Meier’s Civilization as a supporting tool to teach the relationships between military, technological, political, and socioeconomic development has been so successful for educators, that a purely educational version of the game was announced for 2017. Here, the core loop is closely aligned to the educational objectives. Your core play is all about figuring out the right combinations economic development, exploration, government, diplomacy, and military conquest to create a successful civilization.

Question 3: Is Your Core Loop Connected to All the Ingredients of an Engaging Experience?

As I’ve mentioned in a previous article, the ingredients of engagement go beyond game mechanics; they include other things like art, theme, story, and community building. When you are able to connect your loop to these other ingredients the engagement is much more powerful.

In Toontown Online for example -a game developed by Disney in which the overall goal was to defend a cartoony world from invading business robots- we wanted to make sure that the core loop reinforced the overall Theme of the game. This Theme was something like: “Work is always trying to take over our play time, but play most prevail” so we included as an essential part of the core loop to stop the robot invasion the need to play. Without playing arcade-like minigames you could not earn jelly beans, the main currency that was essential to buy gags that would help you stop the business robot invasion. So even when the story and main conflict was about defending Toontown and battling business robots, you couldn’t do it without playing and having care-free fun. The result was a core game loop that reinforced the Theme of the game, the conflict between work and play, and because the Theme resonated with many players beyond our original target -kids between 6 and 12- the game ended up being very popular with players well beyond our target demographic. Also, as you repeated the loop, the game prompted you to explore other parts of the world, team up with other players and make friends, and unfold new stories. In other words it pushed you to discover new art and stories, build community, and master the mechanics, which made the game much more engaging. The result was an average player lifespan much higher than most other family oriented games at the time, which made the game very profitable for over 10 years.

The more you are able to connect your core loop of activities to the ingredients that make a game engaging, the stronger and longer engagement you will have.

Conclusion

Clarifying what is your core activity loop is a powerful tool to make your game or experience more engaging. Once you clarify your loop, these three sets of questions will help you shortcomings and opportunities to make your game more engaging and successful:

1.Are the activities in your loop compelling enough? Do you provide enough positive feedback when players complete the activities? As players complete a loop do they get something that makes them feel invested?

2.Is the loop directly linked to your objectives? If you are selling something, does that make the loop more satisfying? If you are teaching something are the core activities directly linked to the topics the player needs to learn?

3.Does your loop reinforce the different ingredients of an engaging experience? As players go through the loop, can you provide more things to discover and get mesmerized by? Can you add more interesting pieces of a story? Can you guide the player into forming a tighter community?

Do these questions trigger for you new ideas on how to improve the game you are working on? Please let me know in the comments.(source:gamasutra)

下一篇:适合小型游戏快速创建原型的方法

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号