万字长文,关注游戏的平衡设定及其与公平实现的关联探讨,下篇

篇目1,解析可运用于游戏设计中的平衡理论

作者:John Graham

每款现代即时游戏都包含某些形式的石头、剪子、布机制。玩家潜意识中知道此类机制的存在,而且它们运转良好,但是没有人解释其中的缘由。通过些许游戏理论,我能够向你澄清其中的原因。但是首先,我需要先给你提供些许简单的游戏理论定义。

何为游戏?

游戏是个保量两个或更多玩家的框架,每个玩家的胜利不仅取决于自己的战略,还取决于游戏中其他玩家所采取的战略。

何为战略?

战略是玩家解释自己将在游戏中如何表现的完整动作计划。

何为优势战略?

优势战略指在所有情境中与所有其他战略效果相同,但在至少1种情境下优于其他所有战略的特殊战略(游戏邦注:比如在含有石头、布和散弹枪的游戏中,散弹枪就是优势战略)。

获得胜利的方法

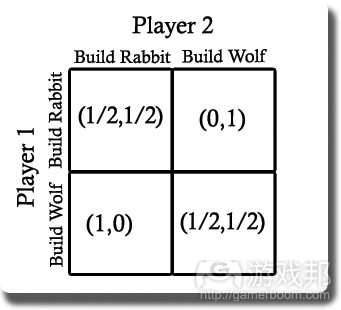

让我们以电脑游戏为例来解释上述内容。假设两个玩家正在玩名为《Lugaru Wars》的RTS游戏。每个玩家拥有的资源只够制造1只狼或1只兔子。假设游戏胜利者可以获得1分。同时,假设狼总是能够打败兔子。最后,我们假设狼与郎,或兔子与兔子之间战斗的胜率各方均为50%。下图显示游戏的情况:

Rabbit vs Wolf(from blog.wolfire)

结果以(X,Y)的形式呈现,X代表玩家1获胜的几率,Y代表玩家2获胜的几率。

从结果模型中可以看出,很显然制造狼是种优势战略。如果我的对手制造兔子,而我制造的是狼,那么我就能够获得1分,但我制造兔子只能获得1/2分。如果我的对手制造了狼,而我制造的是兔子,那么我无法得分,而我制造狼可以得到1/2分。无论出现何种情况,选择制造狼的结果总是比较好。这个游戏的设计不平衡,因为任何想要赢的玩家都会一直制造狼,而兔子永远都不会在游戏中出现。当每个玩家都制造狼时,游戏就会发生“纳什均衡”(纳什均衡指的是这样一种战略组合,这种策略组合由所有参与人的最优策略组成。即在给定别人策略的情况下,没有人有足够理由打破这种均衡)。

平衡但乏味

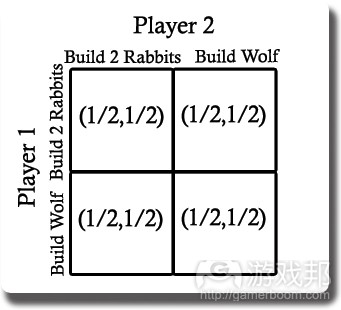

这种情况要如何弥补呢?假设狼的力量是兔子的两倍,那么当2只兔子遇上1只狼时,获胜的几率也会是50%。那么,平衡这款RTS的最快方法是让制造兔子所耗费的资源变成狼的一半。那么现在,使用同样的资源,玩家可以选择制造1只狼或2只兔子。这样,结果模型如下图所示:

2 Rabbits vs 1 Wolf(from wolfire)

在这样的游戏中,制造2只兔子的战略和制造1只狼的战略效力相同。有人会辩解说,经过这样的修改,兔子也会在游戏中出现,我们的目标实现了。但是,这样的游戏仍然很乏味无趣,因为玩家完全无需考虑自己要制造什么和对手可能制造什么。每个人都会想:只要我花费所有资源来制造单位,无论制造什么胜率都是50%。

融合

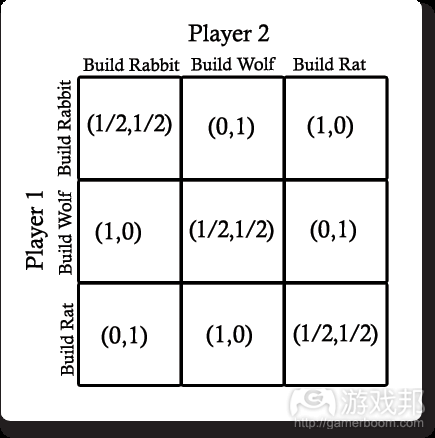

以上两个都是乏味无聊的例子。让我们通过添加新的角色来让游戏变得更加有趣。假设玩家依然只能选择制造1个单位,但是现在他们的选项有3个:老鼠、狼和兔子。在这款游戏中,我们假设狼可以打败兔子,但是老鼠足够狡猾,可以伏击并打败狼。最后,假设兔子有敏锐的听觉,可以揪出潜伏的老鼠并将其打败。那么,这款游戏的结果模型就如下图所示:

Rabbit vs Wolf vs Rat(from blog.wolfire)

现在,游戏就不再有优势单位,而且每个玩家都会想知道其他玩家做出何种选择,这样他们才能选择能够战胜对手的单位。游戏再次实现平衡(游戏邦注:每个单位在游戏中都有优势),而且不存在明显的优势战略。在这样的平衡游戏中,不存在纯粹的战略“纳什平衡”,只存在利弊共存的策略性“纳什平衡”,玩家选择任何单位的可能性都是相同的。

如果你想要向玩家提供超级战略,可以设置超级战略需要消耗玩家一定比例的能量,这样他们就无法频繁执行超级战略。更为重要的是,确保游戏中没有在所有情境中通用的超级战略。游戏设计师的任务就是要通过结合弱势来对抗优势,这样玩家就不会一次次地重复使用相同的优势战略,他会发现在某些情境下自己必须采用新的战略。

我如此喜欢《复仇格斗兔》的原因之一是,它不仅没有优势战略,而且还通过AI来惩罚那些重复使用一种攻击方式的玩家。因而,玩家被迫试验不同的战略,并且习惯于在游戏中使用多种战略。

篇目2,保持游戏平衡性并不等同于实现公平性

作者:Max Seidman

平衡并非公平

平衡经常被当成是调整数值以确保游戏公平的过程。这经常需要承担着摆脱“主要策略”(即当被选择时,策略能够帮助玩家更轻松地获胜),并确保没有一个组件远超于其它组件的责任。平衡通常也包括一些调整,就像确保首个玩家不会比其他玩家拥有更多优势等等。

这是关于平衡角色的一个非常局限的视角,主要存在一个主要原因:为了公平的公平是不必要的。我们很容易想象一款完全“公平”的游戏是一点都不有趣的,例如:“所有玩家滚动一个骰子。不管谁,只要滚到最高值就算获胜。”这样的游戏是完全公平的,但结果却是彻底无聊的。这一理念也可以延伸到特别的组件中—-如果《万智牌》中的所有纸牌都是一样的(或者功能相似),玩家将不再拥有任何有意义的选择,游戏便会非常无聊!

fork-in-the-road(from blogspot)

什么是平衡?

最近在社区中有一些关于平衡游戏策略的文章,即专注于如何做到公平。尽管获得公平是平衡的结果,但平衡并不是关于避免提供给玩家超越别人的优势。平衡这一词指的是不去平衡玩家获胜的可能性,同时也不是在平衡纸牌的能量:这是关于平衡玩家所作出的选择。从核心来看,策略游戏是关于选择的紧张感:我想要做A或B,但我却不能同时做这两件事。我们平衡了这些决定去确保玩家总是会拥有其中的一种紧张—-如果所有的这些选择是不平衡的,那么这种紧张感便会消失。平衡是调整数值(游戏邦注:资源,可能性,选择等)去确保玩家在轮到自己的时候至少拥有两个有趣且同等吸引人的选择的一种行为。

就像我所说的那样,这种对于平衡的理解也仍然能够实现公平。例如,想想玩家正在选择纸牌。如果任何纸牌都比其它有利,那么玩家便没有有意义的选择。

这样的理解存在怎样的实质性差别?

让我们以《万智牌》为例。如果《万智牌》的研究开发团队将“平衡”理解为“创造所有公平的策略,”那么他们便会基于任何特定的设置将5个颜色的万智牌设计为你的桥牌的平等选择。如果是将平衡理解为“平衡玩家的选择,”《万智牌》的设计团队将创造一个带有一些较棒的单独纸牌但却能量不足的颜色。从选择平衡框架去思考这一设计,这将很容易创造出一个有趣的选择:想想一个玩家打开他们的第一个游戏包但却只发行一张普通的红色纸牌(红色是这一设置中可以选择的一个强大的颜色),以及一张真正强大的白色纸牌(但是在这一设置中白色是一个相对较弱的颜色)。对于玩家来说这绝对是一个有趣且有意义的选择,并且是我能够称为平衡的内容(假设一个选择并没有比其它选择好多少),不会强迫策略(颜色)或独立组件(纸牌)足够平等或“公平”。

关于平衡你的目标是仔细考虑玩家在游戏过程中所面对的选择点,即每个点平均有2至3个有意义的选择。有时候一个选择(或没有选择)是合理的,特别是在游戏一开始。超过3个选择也是可行的,特别是在游戏伴随着高重玩性,或在之后的游戏过程中(从基本上来看,更多选择的出现也就意味着玩家必须更加清楚他们在做些什么,如此才能避免被选择所淹没)。

在这里,有意义的选择(或者错误的选择)的理念是相对重要的。通常情况下,表面上玩家会遇到许多选择,但却只有其中的一些选择是有意义的。让我们再次以《万智牌》为例,如果我决定创造一个红绿色桥牌,那么我必须从一个纸牌包中选择15张纸牌,但通常情况下只有6张纸牌是符合我要的颜色(让我能够忽视白色,黑色和蓝色纸牌的错误选择)。在这6张纸牌中,也许只有2至4张将是最棒的选择,在这之后我必须做出决定。拥有这些错误的选择并不是糟糕的设计,因为它们也能让玩家的体验便等更轻松,且创造出重玩价值。然而,设计师必须意识到两点内容:首先,每个决策点拥有平均2至3个选择是忽视错误选择的做法,其次,错误的选择看起来像是有意义的选择会混淆新玩家。

使用这一框架

现在离Seth Jaffer写下一篇关于平衡游戏的具体步骤的文章(使用传统的“平衡”定义)大概过去了一个月。尽管这真的是一个很棒的参考内容,但它却漏掉了平衡最重要的一步—-即通过理解平衡作为确保玩家选择紧张感的重要元素的这一步。作为设计师,你必须先明确你的游戏决策点以及玩家将在这些点上做出的潜在决策。如此你才能知道如何分配数值和可能性去确保在每个接合点会有2至3个有意义的选择。

举个例子来说吧,我正致力于一款带有“否决选择”机制的游戏。在每个回合中,玩家将从桌上的一排纸牌中选出一张,并询问其他玩家她是否拥有那张纸牌。每个玩家都有机会拒绝纸牌,即通过支付一定的胜利点数。如果他们不这么做,便需要持有那张纸牌。如果他们这么做,便有机会去选择不同的纸牌。“我该问对手桌上的哪张纸牌是他所拥有的呢?”这是游戏中最大的决策点。玩家在那时刻的选择是:

1.“我是否该询问我的第一张选择纸牌,假设我的对手将会把它给我?”

2.“我是否该询问我的第二张选择纸牌,希望对手将花钱否定这一选择,然后我便能够选择我的第一张纸牌?即使他们并未否定,我也能得到一些好处。”

3.“我是否该询问一些我知道别人想要的,但是我却没有的,为了让他们能够支付给我VP,然后我们便能够获得我的第一个选择?如果他们并未否定,我是否会陷入一些糟糕的情况?”

4.“我是否该尝试我手中的一张纸牌?”

这一目标是让玩家能够在每个回合分布于这些选择中的2至3个,即伴随着偶然的1个选择回合或4个选择回合。一旦设计师在玩家的决策点上理解了玩家的决策,他便能够分析游戏去决定哪个游戏元素或数值可能创造出一些错误选择。在我的游戏中,这是一些可能导致上述某些选择失衡的内容:

每张纸牌的平均胜利点—-每张纸牌选择也会提供给玩家胜利点。如果一张纸牌可以获得更多胜利点,它便能够更轻松地让对手否定一个选择,如此玩家便更加不可能选择上述的第1个选择。这具有很大的风险。

适合分数方案的数字—-玩家为了获得更多点数尝试着收集带有同样套组的纸牌。当分数方案中拥有更多套组的,每张纸牌对于投入收集纸牌的玩家来说将更有价值,反之亦然。收集这类型纸牌与并未收集这类型纸牌的玩家间的区别越多,玩家便更加不可能选择上述的第3个选择,因为你将不得不接收一张你并未在收集的纸牌。

否定胜利点需要花费一定的成本—-如果玩家否定敌人最初选择的成本越高,他便越不可能去否定它,从而导致玩家越不可能选择上述的第2或第3个选择,因为在这两种情况下玩家更有可能面对一些不属于他们最初选择的内容。

手上的纸牌数量—-因为玩家有时候可以直接使用手上的纸牌,那么当玩家手上的纸牌数越多,他便越有可能具有一个明确的策略,如此他便越不可能挑选第3个选择,并且越有可能指向第4个选择。

这一游戏的核心平衡是否定一个具有足够吸引力且玩家总是会考虑到的选择,而不是玩家总是指望着自己的第一个选择被对手否定。牢记着这点,现在我便可以使用Jaffee的5个步骤去平衡游戏元素。

所以下次,当你准备平衡一款游戏时请记得:当你在平衡时,不要首先想着要让游戏元素足够“公平”。你的主要目标应该是确保游戏中的内容数能够在玩家的每一轮尝试中提供给他们有趣的选择。

公平并不总是件坏事,但它却有可能阻止你创造出更重要的设计,并且如果你不能有效使用它便可能最终破坏你的游戏。

值得注意的是并不是所有的公平形式都是源于我的平衡框架,即用于确保有趣的玩家选择。举个例子来说吧,确保玩家总是拥有有趣的选择并不一定意味着先走不是一个巨大的优势。这是我们应该考虑的关于公平本身的元素。

篇目3,阐述个性化的价值及保持游戏平衡性的建议

作者:Josh Bycer

在游戏中,个性化是给予玩家进展和选择的最佳方法之一。允许玩家根据自己喜好创建一个角色或者一支军队,可促进他们与角色的互动,这也是保持他们游戏激情的一大动力。《军团要塞2》所采用的大量道具就是给予游戏重玩价值以及增加游戏寿命的典型之一。随着个性化地流行,更多的设计师也开始在游戏中引进这种元素。

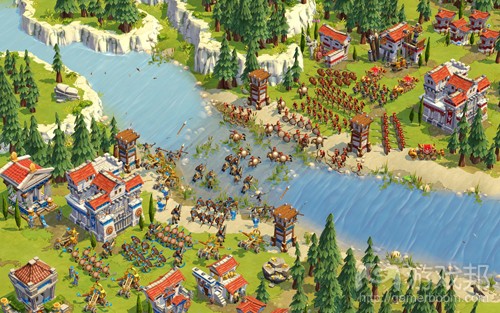

在《暗黑破坏神3》中的5个职业中,每个职业都允许玩家混搭其中的积极和消极技能,允许两个玩家使用同种职业,但是作用却不大相同。在《帝国时代Online》,你可以配备各种可建设的单位,构造不同的武器,也可以把顾问带到提供特定时代加成的战役中。

虽然这些设计从理论上看很棒,但我们在执行这种设计时也要谨慎,以免只见树木不见森林,忽视了游戏中的平衡性问题。在讨论游戏中的平衡以及个性化上,我们需要着眼于两个方面:单人/合作,以及竞争设计。

Age of Empires Online(from pcformat.techradar.com)

不可提供无用的选择

设计师在设计合作类游戏时,一般会给予玩家各种各样的选择,并观察这些选择如何在玩家合作(而非相互对抗)过程中取得平衡。我在之前文章中曾提到一个问题:在制作困难的游戏时,有些设计师常会设计出一些无用的选择。

我们观察《暗黑破坏神3》在游戏中段(normal-nightmare)和末段(Inferno)时不难发现这是一款另类的游戏。在Inferno中,许多技能变得完全无效,其生命点降至之前创建时的水平。除此问题之外,由于《暗黑破坏神3》的系统问题,我们很难去判断敌人命值的底线。

由于每一职业的破坏力和防御力取决于其主要属性,无法找到与之相关战利品的玩家就会处于极大的劣势中。但是对于使用拍卖系统的玩家来说,他们只需购买与其职业相关的战利品就能更轻松地驾驭游戏。

还有个问题,就是一个角色拥有过多渗透作用,这导致游戏结局几乎不可能实现平衡。游戏中的五个不同职业都拥有所有技能和符文,加上未使用拍卖系统的玩家所得到的随机战利品,另外游戏还得根据使用拍卖系统的玩家来调节平衡性。因此暴雪在此不仅是搬石头砸自己的脚,甚至可以说是自截下肢。

得益于装备布局和升级系统设置,玩家更容易在《恶魔之魂》中获得平衡感。设计者根据预先设定的装备定位以及视情况而变化的敌人属性,妥善设置了每个阶段的角色属性的基本属性。当然,知道如何让装备和属性发挥更高效能的骨灰级玩家仍会在游戏中遥遥领先,但这并不影响整体游戏平衡性。因为根据少数的硬核群体来平衡游戏,通常只会促成平庸无趣的设计。而你在这种混杂情形中注入竞争元素时,这种设计就更具挑战性了。

竞争角度

平衡性对合作型游戏设计来说非常重要,但对竞争型游戏来说,平衡性设置是否妥当则可能直接决定游戏的生死。高手玩家会不遗余力地试图寻找设计中的一些小瑕疵来获得竞争优势。如果游戏失衡,那么高手玩家就不会触碰这款游戏,游戏也就没有竞争趣味可言了。

对《星际争霸》中的高手玩家来说,平衡性正是游戏大有人气的主要原因之一。设计师不仅平衡了三个非对称的种族,甚至还将每个单位的属性精确到了小数点。从这方面来看,《星际争霸》的设计确值得借鉴。

封闭系统是竞争型游戏实现平衡的关键,这意味着在此等式中没有变量的存在:《星际争霸》中的SCV每次都会以相同的速度收集相同数量的矿石。

问题在于,当设计者赋予玩家自定义战略的能力时,这一等式就相应地出现了变量。如果这些变量总会催生出一个最佳策略,那么骨灰级玩家就会发现并利用它,直到该变量变化为止。对于竞争型游戏而言,玩家的技能水平才是导致成败的首要且关键因素。如果玩家只需通过投入时间或者花钱就可以提升装备的级别,多花数小时就能打败对手,那么竞争型玩家就不会再体验这款游戏了。

战略游戏在数据上更具开放性,所以它更容易分析。对于这些想要在战略游戏中更有竞争力的玩家来说,数字游戏是一项重要的学习工具。在《帝国时代Online》中,可个性化单位的道具和升级奖励很棒,但同时它们也妨碍了游戏实现平衡性。

一个相当好的例子是,一个埃及枪手可以通过升级奖励而变身为冠军战士。这种升级不只提升了它们的属性,也节省了每个单位10个黄金的成本。这意味着,如果某人研究了这项技术,升级了15个枪手之后就可以看到这项研究的回报。如果两个玩家互相对抗,若其中一方没有为自己的文明科技研究进行这类投入,那么他就会处于巨大的劣势。

有了这些道具,它们就会有效地破坏游戏的平衡性。给予原本只够对抗其他同类的弓箭手足够的防御和攻击力,那么它就可以损害任何单位。若是再增加防御能力,即使另外一个对手强大到足以对抗它,那么它比对手多30%的命值也仍是一种战斗优势。

starcraft(from 552gaming.com)

想象下,如果玩家可以在《星际争霸2》开始前选择一些特殊的升级方式:比如所有的Hydralisks都无需花费任何vespane gas成本,那么可想而知游戏系统将严重失衡。

提供个性化体验需要设计师对游戏平衡性高度敏感,以下是一些防止游戏系统失控的小建议:

1. 开闭系统

竞争型游戏应为玩家提供一套学习和创建战略的系统。但这并不意味着设计者不可提供多样性选择。

在《命令与征服:绝命时刻》中:这个扩展内容采用了三个可玩选项,美国、中国和大伦敦政府。每一方都有三个次级派系。每个次级派系都有各自长处,并可根据特定需求而改变战略。例如,选择美国空军可能减少玩家可创建的坦克数量,但却可以让他们建造更多航空单位,并节省这一过程中的成本。

这样玩家就有机会使用特定的派系来改变他们的作战策略,虽然这是一种多样化的设置,但其系统仍具有封闭性,因为玩家无法改变次级军力的设置。最近的《太阳帝国的原罪:起义》也沿用同样方法,把三个种族各分为两个次级派系。每个派系都有不同的加成奖励、单位、科研技术和超级单位。

2.大量的限制条件

未经检验就给予玩家大量与角色有关的选项可能导致游戏失衡,但可以通过添加限制条件来避免这种情况。在《帝国时代3》中,玩家可以在游戏过程中向自己的基地运送资源、额外单位和升级内容。但玩家虽然可以解琐并获取这一切内容,但他们能带入战斗中的东西却有一定的限制。

基于此原因,玩家需要根据自己的文明所需要的策略,创建不同组合的运载物资。你重视的是一个文明的优势 ?还是致力于攻克其薄弱环节?或者想成为万事通?没有哪个玩家可以让自己那方坚不可摧,就像每个运载物资未必都有足够的可安放位置一样。这一点与《帝国时代online》相反,后者允许玩家配置一切更强大武器。这意味着人们玩游戏的时间越长,他们的文明就会越发达。

3. 测试多样化设计

如果不再次提到《军团要塞2》,本文关于个性化的平衡性讨论则无法完整收尾。Valve已经不遗余力地让《军团要塞2》尽量保持一种平衡状态,虽然其中植入了许多我根本数不过来的道具。尽管它过去有些道具设置出现了一些问题,但是Valve已经随着时间发展优化了这些设计。

所谓的“Side Grades”为职业带来了独特的加成,但它们也会带来一些负面因素。要避免任何一个道具成为所有情况中的最佳选项,就要适当减少其损害值,弹药等要素。这种做法的最大好处在于,在《军团要塞2》中投入更多时间的玩家无法轻易打败技能更高超的玩家。无论你使用哪种狙击枪或武器,瞄得准打得狠才是王道。

需要注意的是要让游戏保持平衡性,每个道具都必须在某些方面是一个次级选择。

给予玩家更多玩法选项,似乎是帮助玩家不在游戏中输掉的好办法。但是当游戏出现更多有效变量时,游戏也就有更多内容需要测试。如果开发者希望在过后增加更多的选择或者PvP选项,就要确保游戏根基稳固而不受影响,否则整款游戏就会分崩离析。

篇目4,阐述零和机制对游戏平衡性的影响

作者:Soren Johnson

在零和游戏中,一名玩家有所得,那么其他玩家必然有所失,从而实现得失平衡,这就好像打完手牌后赢到一堆筹码。根据严格的游戏理论,许多竞争型游戏并不是真正的零和。以足球为例,射门得分并不是从另一队的得分中扣掉三分。

然而,更宽泛地说,“零和机制”这个词意味着损害对手好比是让自己获得相等的价值。在典型的RTS如《星际争霸》中,玩家经常使用突击策略,目的是尽快破坏敌人的经济,这种方法就像发展自己的经济一样可行。只要可以快速摧毁敌人的第一个单位,无论自己的军队发展到什么程度都没关系。

Zero Sum(from recruitingblogs.com)

因此,只要游戏对玩家阻碍敌人的奖励与增强自己的奖励相当,这款游戏就具有零和机制。大多数团体运动(篮球、英式足球、美式足球等)都有这个特点:防守(阻止对方得分)和进攻(争取己方得分)一样重要。

竞争型游戏的零和特点就更加根深蒂固了。格斗游戏的平衡方式是,以损害对方的命值来保护自己的命值。策略游戏鼓励玩家破坏敌人的计划,同时保护自己的计划。而在射击游戏中,玩家要尽可能多杀敌人,同时执行某些平行任务,如占领旗帜或关卡。

事实上,当设计竞争型游戏时,零和机制就是一个默认选项。然而,这种机制的普遍存在掩盖了许多许多问题。的确,从最好的方面讲,零和机制是不可避免的恶;从最坏的方面讲,零和机制是游戏设计中犯下的顽固错误,使许多玩家离开游戏。

零和问题

零和机制的问题是,给某些人带来消极体验——眼睁睁地看着自己的角色在《街头霸王》中被消灭,看着自己的建筑在《帝国时代》中崩塌,看着小队成员在《军团要塞》死了一个又一个。一名玩家的快乐来自另一名玩家的痛苦。

其实,竞争型游戏不需要让另一名玩家受苦。游戏的规则决定了玩家交互活动的频率和程度。基本上,设计师决定了玩家在游戏中如何产生交互活动。确实,竞争型游戏甚至可能不存在玩家之间的相互影响——想想平行运动,如高尔夫球和保龄球,或带有异步排行榜的在线游戏,如《宝石迷阵闪电战》和《Burnout Paradise》。

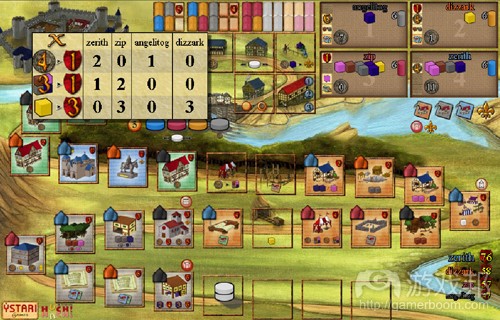

是重要的区别是,玩家是否损失当前进度或是否只丧失了继续前进的能力。对于前者,在带有零和特点的游戏机制中,失去进度通常是一段不愉快的体验,往往是失败的必然之路。相反地,德式桌面游戏的一个明显特点是避免这么直接、零和的玩家斗争,而倾向于有限的、间接的交互活动,以避免破坏玩家的进度。

例如,在德式桌面游戏中,如《Agricola》和《Caylus》,玩家轮流选择独有的技能;玩家想方设法夺得决定谁得到最佳工作的地位。如果玩家知道自己的对手需要食物,就给自己选择食物的工作,这样就会使对手的财富受到重大损失。然而,与在《帝国时代》中破坏敌人的农场和杀害敌人的村民相比,这两种策略存在本质的差别。

Caylus(from dahus.info)

在前一种情况下,消极作用可能只是暂时的;而在后一种情况中,玩家的情绪会受到严重的打击,并且恢复的机会很小。其实,在《Agricola》中,花太多时间破坏对手的玩家往往也要付出代价,因为每一次破坏行动都要支付珍贵的机遇成本。相反地,在RTS中,尽早破坏对手却没有害处;摧毁另一名玩家的经济事实上可以为自己的建设发展争取到宝贵的时间。

平衡RTS游戏,不奖励提前破坏其他玩家经济基础的行为,是极其困难的。确实,零和机制在RTS游戏中起的主导作用太强大,可以说因此鼓励了玩家采用突击战术。许多玩家采用“非突击”的自订规则,人为地重新平衡游戏玩法,以免突击战术过早地结束游戏。

进一步地说,许多RTS游戏结束得无声无息,而不是以大战一场收尾,这是因为游戏的终极目标就是摧毁敌人的军事,这意味着在游戏进行到一半是,结果就很明显了。在《车票之旅》中,玩家在用完组件以前要竞争路线,玩家的紧张情绪是不断升级的。而在《星际争霸》中,玩家的紧张情绪先是上升然后下降——不幸的是,下降的部分对于失败者来说纯粹是件痛苦的事。

然而,零和机制不仅限于RTS游戏。经济游戏,如《Anno》、《铁路大亨》或甚至《M.U.L.E.》,主要的目标获得财富、看谁积累得最快,因此游戏不必鼓励或允许一名玩家攻击另一名玩家。

在军事RTS游戏中也可能出现竞争型机制的替代品。《魔兽争霸3》引入了中立角色,这类角色占领冲突地图的中心区域,玩家抢先杀掉中立角色才能得到经验点和奖励。也许新的RTS可以进一步采用这种机制,使游戏的焦点只放在杀死中立角色上?

减少消极作用

许多竞争型游戏解决零和问题的方法是,严格地限制交互活动,使玩家就只能在某种情况下影响彼此。例如,在《马里奥赛车》中,玩家只有在某个地点捡起限制使用次数的炮弹后才能射击另一名玩家;甚至之后,玩家只有在比赛中尾随才能得到最强大的炮弹。在残忍的RTS中,除非玩家建完第一个兵营、训练了军队、最后将军队领到战场,否则就不能进攻。

因此,最小化零和玩法的消极作用,限制玩家的交互活动是非常有效的方法。根据允许哪一类交互活动,带有相似主题和规则的游戏可以极大地改变游戏玩法。例如,《部落战争》和《Empires & Allies》是相似的异步即时战略游戏,玩家要发展军事,然后进攻敌人。然而,这两款游戏之间存在重大区别,从玩家入侵对方的城市时发生了什么事可以看出来。

在《部落战争》中,进攻是严格的零和的;进攻者从防守者的贮存中获得资源。而在《Empires & Allies》中,战斗是正和的;进攻者是凭空得到资源的。另外,《部落战争》中的死亡单位会从游戏中消失,而《Empires & Allies》中的防守单位总是活着,即使被打败了。

empires & allies(from mobiletmt.com)

《Empires & Allies》秘密地掩饰了玩家对战斗的预期——胜利需要战败方,这个设计选择很有效,因为它使游戏更容易玩,玩家的情绪不会受太多影响。相反地,《部落战争》采用的是传统的方法,即一名玩家的获得需要另一名玩家的损失。这种设计选择创造了一个险恶的游戏世界,里面尽是坏脾气、野蛮的玩家。

许多设计师本能地认为,斗争必须是零和的,但这种偏见可能会导致很多玩家不玩他们的游戏。玩家在游戏体验中产生的情绪已经足够真实了,所以需要玩家至少遭受一点儿情绪损失的机制,应该谨慎使用。

增加积极作用

有时候,替换方法实在太简单了。在桌面游戏《七大奇迹》中,玩家的竞争路线有多条——科技、文明、建筑、财富和军事。在这类游戏中,默认执行军事行动的方法是,允许玩家培养军队进攻其他玩家的单位、建筑或资源。然而,《七大奇迹》却采用了非常不同的方法。

该游戏分成三个时期,在各个时期的末尾,具有最多军队的玩家得到正得分,而其他玩家得到负得分。此外,总得分的分配是正和的,所以战败对玩家的损失程度不会与战胜的获得程度相当。因此,军事策略并不会使其他竞争路线变得可有可无。游戏的平衡性是比较良好的:自己的强大军事不会防碍科技强大的对手获胜,因为军事胜利不会导致失败方损失进度。

确实,正和玩法的优势也有利于游戏设计的其他方面。以《益智之谜》为例,通过保证每一次战斗都是正和的,从而避免玩家手动保存系统。玩家在战斗中不会损失道具,且在每一次战斗中总会得到至少一点点金钱和经验。因此,玩家在战斗结束后总是进展得更好了,无论战斗本身是输还是赢。所以,游戏可以不断地自动保存。这种功能与传统的零和设计相比,可能太硬核了。设计师没有移除载入/保存系统(这样会阻碍新玩家进入游戏),却拓宽了游戏的普及范围。

基本上,零和机制仍然是游戏设计师的强大工具,因为它们可以唤起玩家的情绪。有时候,允许玩家互相破坏正是游戏必需的。然而,并非所有斗争都必定是零和的,特别是因为这种设计选择具有极大的缺陷。毕竟,不一定要采用让失败者受苦,胜利者才能成功的玩法。

篇目5,Richard Garfield分析保持游戏平衡性的策略

作者:Leigh Alexander

这周末在纽约大学,我有幸聆听了《Magic:The Gathering》创作者兼资深设计师Richard Garfield关于游戏平衡策略的演讲。

Garfield可能是目前最具创造性与影响力的设计师之一,他负责制作了无数款已深远影响设计与行业模式的实体游戏。然而即使是在他看来,游戏的平衡性仍是个宏大话题。

鉴于游戏类型的多样化,我们难以对它们进行笼统分析。Garfield指出:“假如,你是一位正在探讨生命的生物学家,那么你是无法分析如此繁多的生命。你应该选取其中某个部分,然后‘着重探讨这一方面’。”

正交游戏的平衡

为了能够探讨游戏的平衡性,Garfield选取正交游戏作为论述重点,他将其定义为有限的多人游戏(游戏邦注:包括两位或两位以上玩家的游戏),游戏最终会对玩家分数进行排名——比如桥牌与棋盘这些经典游戏便属于这一类型,而《FarmVile》不属于该范畴。

Garfield解释道:“我们用策略性失败来定义平衡性。这意味着,玩家可以在游戏中采取一系列策略,如果有些策略在游戏中不可行,而玩家认为它们本该具有可行性时,这时,人们就会认为这种现象为失衡状况。”

当玩家总是选择某个更具可取性的战略时,策略失败现象便会发生。在《Magic》的竞赛环境中,寻找各种平台类型是检验竞赛安全性的优良渠道。更多的平台类型可以确保游戏平衡,而游戏中只存在一个可行平台则会降低游戏的趣味性。另一方面,过多的平台类型则会给大部分玩家造成更多困扰。

Garfield表示:“毫无疑问,这样会引申出更多策略。”

有时,策略失败与策略本身毫不相关。比如,首个开始井字游戏的玩家,他的获胜率更高,因此,对手可能会仅仅因为自己并非领头羊而失去对游戏的兴趣。

同时,Garfield强调了平衡性玩法失败的概念——所有玩家都会采取不同的方法开始游戏进程,而你的方法如果在游戏中并不是很占优势,那么你可能就会认为游戏不具有平衡性。

看待平衡的两种方式

Garfield认为游戏平衡可分为两类:整体性与部分性。当某款游戏中包含的单独组件需要保持平衡时,这就归为部分性平衡——《Magic》中的闪电球只消耗一个红色魔法吗?在《暗黑破坏神》中,一件装备能够为你增添152个智力值吗?相反,整体平衡注重将游戏当作一个整体——在《Magic》中,你是以20点生命值还是7张卡片启动模式的?在《暗黑破坏神》中,你可以兜售装备,换取真实货币吗?

他解释道,有时这种区别界限十分模糊,但区分性地讨论游戏平衡仍具有一定作用。

Garfield表示:“通常,设计师会设计出符合骨灰级玩家平衡定义的游戏。当然,我们在早期制作《Magic》时便有这种想法,而且,我经过了一段时间才逐渐摆脱这种固定思维。”

其实,迎合骨灰级玩家,忽略其他类型玩家的平衡模式实则是个失衡体验,在大部分玩家发展技能水平,达到完美平衡的体验之前,他们会纷纷离开游戏进程。同时,骨灰级玩家也会失去合作对象。

而且,针对骨灰级玩家的平衡模式常常忽略了一点,即某些玩家的精通水平已超越游戏本身。设计师不一定是顶级玩家,其实,大部分时候,他们并不属于出色玩家。

所有游戏都会附上规则,帮助玩家理解游戏进程。其实,大多数时候,平衡性有助于玩家快速提高技能,这对表现不佳者极其有益。

重要的是,游戏应提供更多选项,方便所有类型的玩家做出自己的正确选择,这与按照玩家使用技能或职业方式是否正确来进行分组完全不同。即使玩家并非机械性地集中精力,他们也能对抗,如同角色扮演玩家或故事粉丝一样。

其中有些玩家会根据角色外貌或叙事背景为它们选择装备,而如果其他玩家更为成功,他们就会感觉自己需要被迫放弃这种游戏风格,这也会让他们的游戏体验产生失衡感。

magic the gathering(from giantbomb.com)

平衡策略

Garfield指出:“平衡是一门艺术,不是技术。”数学确实在Garfield的游戏设计中发挥了作用,但它却无法取代扑克玩家打算了解的游戏复杂程度。

他表示:“我认为游戏中不存在公式。如果你还未解决游戏,那么,要想出平衡游戏的公式似乎是个难题……而且不同用户所需的平衡性又各不相同。如果你解决了游戏,保持了平衡,那么这种平衡性只符合骨灰级玩家,我们已经阐明这是你不能采用的做法。”

而且用户也在发生变化:新手转变为一般玩家,再到骨灰级玩家,年轻玩家转变为年长玩家。Garfield指出:“这是一个移动目标。因为这主要涉及心理状态,与数学无关,因此你不该期待游戏中存在某个精确公式。”

包含大量测试与灵活创建游戏原型的迭代设计方式是找到游戏自然平衡的关键——《Magic》经历了两年测试。“我已经多次尝试将游戏设计为文档形式……但我们确实难以从内在定位游戏的大致方向,除非,它确实极为接近地模仿了一款你十分熟悉的游戏。”

迭代设计的一大优势是,起初,每个玩家都是初学者,而该范围会随着游戏开发进程的继续逐渐扩大。但其中的风险是,随着游戏经过多次测试与迭代,你会逐渐失去新手与休闲玩家。因此,定期主动地引进新玩家,确保自己可以完美让骨灰级玩家与菜鸟玩家融合在一起。

近来,不少发行商可能会在游戏发行后采取迭代手段,这是一个不错的做法,因为它在发行时制作的平衡性符合新手玩家的要求,而且它可以进行快速调整,吻合不断增长的用户群,以防将新用户拒之门外。

石头-剪子-布

Garfield指出,石头-剪子-布结构是指游戏中的所有元素抵抗某个完全不同的元素,这有助于设计师设计游戏平衡。从部分水平上看,该结构体现在大量游戏中,比如《Stratego》与《军团要塞2》。从整体水平上也是如此,比如《星际争霸》中采取的快速、防御以及单一游戏模式,即每个策略相对于另一个策略具有一定劣势。

Garfield指道:“如果暴雪能够认识到这是一种健全的石头-剪子-布关系,它便会根据这一模式设计。如果他们为失衡游戏创建单位或基础状态,并且制作出可以统治他人的策略,那么他们需要做出一些调整。”

虽然石头-剪子-布本身是一种小型游戏,但它也做出了一些设置:比如,石头并不需要100%地战胜剪刀。只要获胜概率超过50%,该结构便具合理性,其实,许多情况下,我们最好制定这种结构,那样整款游戏就不会局限在单个选项中。在一定范围内选择某个策略只会提高偏爱该策略的玩家的胜算,无法保证完全取胜。

Rock-paper-scissors(from uncyclopedia.wikia.com)

增加成本

另一方面,我们可以通过为需要平衡的组件生成和定义“成本”,从而保持游戏平衡,成本可以源自多种渠道。比如玩家在游戏过程中付费,而且他们最初都处于同一水平。如果游戏设置回合内与回合间成本,那么它们通常属于不同来源,有时,我们难以定义这种成本。

Garfield表示:“重要的是,你应拥有一个,或者一些可以调整组件平衡的数据……开发者掌握成本和得分概念后需要用一个数字来作为主要按钮。随着你深入理解系统,你将会成为这个按钮的调整专家。在《Magic》,一旦我们擅长调整魔力消耗按钮,我们便会熟练操作其它按钮。”

非独霸策略

Garfield提议,我们通过设置一系列成本标准为起点。之后开始发展系统——包括添加新组件,保证它无法凌驾于旧组件之上。由于独霸元素更易凸显其价值,从而导致游戏逐渐丧失维度;通常情况下,未包含独霸元素的游戏可以提供更多的可行选项。

如果某个组件过于强大,你可以采用策略或“管控”组件,或是减少它的功效。《Magic》频繁地采用这类做法;比如,飓风卡可以伤害所有玩家,尤其是飞行物;“如果我碰到对手使用飞行物,那我可以采用这种方案解决。现在如果他们过分依赖飞行物,我就会打败他们。”《星际争霸》中的观察者可以控制隐身术。添加hoser则是让玩家对抗采用特定策略或强大组件对手的可行方式。

通常,hoser会造就石头-剪子-布情境,即策略A是对抗策略B的理想选项,但可能极易受到策略C的制约。

同时,还可以让玩家使用相关游戏元素与功能控制自己的发展曲线,保持平衡的完整性。有时,不一致性也有助于保持平衡——比如,某个在大多数时候不具可行性的策略有时候可能会转变为可行战略。这通常出现在卡牌游戏中。为了调和一个具备强大功能的方法,我们应让它只在某些罕见情况下具有可行性。

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4,篇目5(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

篇目1,Game Theory Applied To Game Design

John Graham

Every modern real-time game has some form of rock, paper, scissor mechanics. As gamers we subconsciously know that such mechanics are there and that they work pretty well but no one ever explains why. With a little bit of game theory I can show you why but first I’ll need to give you some brief game theory definitions.

What is a game?

A game is a framework involving two or more players where each player’s success is determined not only by his own strategy, but by the strategies of all the other players in the game.

What is a strategy?

A strategy is a complete plan of action for a player that explains how he will behave.

What is a dominant strategy?

A dominant strategy is a strategy that does at least as well as every other strategy in all situations but does strictly better than every other strategy in at least one situation. (In a game of rock, paper, shotgun, the shotgun would probably be the dominant strategy.)

One Way To Win

Let’s stitch this together in a computer game example. Let’s say there are 2 people playing an RTS called Lugaru Wars. Each player has just enough resources to either make one wolf unit or one rabbit unit. Let’s assume that winning the game earns the winner one point. Let’s also assume that wolves always beat rabbits (the rabbits are not like Turner). Finally let’s assume that the result of a wolf fighting a wolf or a rabbit fighting a rabbit is a 50/50 toss up where each player’s expected winnings are half a point. Here’s what the game would look like in normal form:

Payoffs are represented in the form (X,Y) where X is what Player 1 has won and Y is the winnings for Player 2. For more information on how to read and understand normal form games click here.

From looking at the payoff matrix, it becomes clear that building a wolf is the strictly dominant strategy. If my opponent builds a rabbit and I counter with a wolf, I get 1 point whereas countering with a rabbit gives me an expected value of 1/2. If my opponent builds a wolf and I counter with a rabbit I am guaranteed to lose and get 0 points whereas countering with a wolf, I can expect 1/2. Choosing to build a wolf makes me better off in every scenario. This game is not balanced because any player who is trying to win, builds the wolf unit all the time every time and the rabbits might as well not be in the game at all. (Bonus Fact: the “Nash Equilibrium” of this game occurs when each player builds a wolf.)

Balanced But Boring

How can this be fixed? Let’s pretend that wolves are twice as powerful as rabbits, so that when two rabbits meet one wolf, it’s a 50/50 toss up as to who will win. A quick fix for balancing this RTS is to make the rabbit cost half as many resource points as the wolf. So now with the same resources each player can build either one wolf or two rabbits. Now the payoff matrix looks like this:

In this game the strategy of building 2 rabbits is just as effective as building one wolf. One could try to argue that our work is done and we will now see a healthy mix of both units being built. However, this game is still very boring because the players don’t care at all what they build or what their opponent builds. Each person says, “Hey as long as I spend all my resources building something, I can always expect half a point no matter what.”

Mixing It Up

Ok, enough boring examples. Let’s spice this up by adding another character. Let’s say that players can again only build one unit each but now they can choose among a rat, a wolf and a rabbit. In this game assume wolves always beat rabbits but rats are sneaky enough that they can always ambush and kill wolves. Finally, the rabbits have such good hearing that the rats can not sneak up on them and rabbits can destroy rats every time. Here’s what the game’s payoffs would look like:

Now is there one dominant unit type that is always the best to build? No. Do players still feel indifferent about what they build relative to what their opponent is building? No, quite the opposite. Now each player really wants to know what the other player is up to so that he can build the right counter unit. The game is again balanced (each unit has equal merit) but there is no obvious strategy. (Bonus Fact: This balance here coincides with the fact that there is no pure strategy Nash Equilibrium in this game, only a mixed strategy Nash Equilibrium where both players are equally likely to pick any of the three units).

If you’re going to allow the player a super-strategy, make its cost to the player proportional to its power so they can’t execute it frequently. More importantly, make sure that the player can’t derive a super-strategy that works in every situation. Game designers have an obligation to combine some weaknesses with the strengths for a given course of action so that instead of dooming the player to repeat his same old dominant strategy again and again he finds himself forced into situations where a new strategy must be derived.

One of the reasons I like Lugaru so much is that not only is it structured to have no dominant strategy, no move to beat all moves, but David actually programmed the AI to punish users that repeat one type of attack too many times in a row. Players are thus forced to experiment and become comfortable with a lot of different moves.

Can you think of any games that are famous for embracing mixed strategies with their careful balance? Do you have any thoughts on how to take these game design concepts further?

篇目2,BALANCE BEYOND FAIRNESS

by Max Seidman

What Balancing Isn’t

Balancing is usually understood as the process of tweaking numbers to make a game fair. This often entails getting rid of ‘dominant strategies’ (strategies that, when chosen, make the player win more than their fair share of the time), and making sure no components are tremendously better than others. Balancing also generally includes tweaks like making sure the first player doesn’t have an advantage over the others.

This is a very limited view of the role of balancing for one major reason: fairness for fairness’ sake is not necessarily desirable*. It’s easy to imagine a completely ‘fair’ game that is no fun at all, for example: “All players roll a die. Whoever rolls highest wins.” This ‘game’ is completely fair, and consequently completely boring. This concept can be extended to exception based components as well – if all the cards in Magic were the same (or similar in function), the player wouldn’t have any meaningful choices and the game would suck!

What Is Balancing?

There have been a few pieces written in the community recently on strategies for balancing games, with a focus on achieving fairness. While achieving fairness is a result of balance, balance is not about avoiding giving one player an edge over the others. The balance that the term refers to is not balancing the players’ likelihood to win, nor is it balancing the power of cards: it’s about balancing the choices the players make. At their core, strategy games are about tensions in choice: I want to do A or B, but I can’t do both. We balance these decisions to make sure that players always have one of these tensions on their turns – if all of these choices are imbalanced, then the tension vanishes. Balancing is the act of tweaking numbers (resources, probabilities, options, etc.) to ensure that players always have at least two interesting and equally appealing choices during their turns.

As I mentioned, this understanding of balancing still achieves fairness. For example, imagine players are drafting cards. If any of those cards is much better than any other, then the player has no meaningful choice.

How Is This Understanding Practically Different?

Take, for example, a Magic draft. If the Magic R&D team had understood ‘balance’ to mean “making all strategies fair,” then they would design each of the five colors of Magic in any given set to be roughly equal choices for your deck while drafting. Understanding balance to mean “balancing player choices,” however, could allow the Magic design team to make one color generally underpowered with a few really great individual cards. Thinking about this design from a choice-balancing framework, this could easily result in fun choices: imagine a player opening their first pack to find a mediocre red card (but knowing that red is a strong color for draft in this set), and a really strong white card (but knowing that white is a relatively weak color for draft in this set). This could definitely be a fun and meaningful choice for the player, and one that I would called balanced (assuming one option wasn’t much better than the other), without forcing the strategies (colors) or individual components (cards) to be equal or “fair.”

The goal with your balancing is to think through the choice points players encounter during the game, and to average 2-3 meaningful choices at each point. One option (no choices) is occasionally alright, especially at the start of the game when more choices could be overwhelming. More than three options can also be okay, especially in games with high replayability, or late in the game (basically, the more choices there are, the more players have to know what they are doing in order to not be overwhelmed).

The concept of meaningful choices (or not false choices) is a relevant one here. Often times players will ostensibly have many choices, but only several will be meaningful. Revisiting the Magic draft example, if I’ve committed to making a red green deck, a pack of cards from which I must choose might have 15 cards total, but usually only 6 or so of them will be in my colors (allowing me to ignore the false choices of the white, black, and blue cards). Of those 6 maybe 2 to 4 will be decent choices, and after that it’s up to me to make the decision. Having these false choices is not bad design, as they actually help make the player experience easier while allowing for plenty of replayability. However, designers must realize two things: first, the average 2-3 choices at each decision point is counted after omitting false choices, and second, false choices that look like meaningful choices can confuse new players.

Using This Framework

About a month back Seth Jaffee wrote an excellent article on concrete steps to follow in order to balance your game (using the traditional definition of ‘balance’). While this was a pretty cool walkthrough, it’s missing the single most important step to balancing – the step that follows from understanding balancing as ensuring tension in player choices. As a designer, you must first identify your game’s decision points and the potential decisions the players will be making at those points. Only then can you know how to assign values and probabilities to guarantee 2-3 meaningful choices at each juncture.

As an example, I am working on a game with a “veto drafting” mechanic. Each turn, the player chooses one card from a row on the table, and asks the other players whether she can have that card. Each other player has a chance to deny that player the card by paying her a flat number of victory points. If they don’t, she gets the card. If they do, she gets to choose a different card. “Which of the cards on the table do I ask my opponents if I can have?” is the biggest decision point in the game. The player’s choices at that point are:

1.”Do I ask for my first choice card, assuming my opponents will give it to me?”

2.”Do I ask for my second choice card hoping that an opponent will pay me to veto the choice, and then I can choose my first choice? Even if they don’t veto, I get something alright.”

3.”Do I ask for something I know someone else wants, but I do not, in order to force them to pay me VP, and then I get my first choice? If they don’t veto, I get stuck with something crappy”

4.”Do I play a card from my hand?”

The goal is to have the player split between 2 or 3 of these choices every turn, with the occasional 1-choice turn or 4-choice turn. Once a designer understands her players’ decisions at their decision points, she can analyze the game to determine which game elements or numbers could make some of the possible decisions false choices. In my game, here are some numbers in the game that can imbalance some of the choices above, reducing player agency:

Average victory points per card – each card drafted also provides the player victory points. The more victory points a single card can score, the easier it will be for an opponent to veto a choice, and consequently the less likely a player is to choose option 1 above. It would be very risky.

Number of suits in the scoring scheme – the players are trying to collect cards with the same suit in order to score more points. The more suits in the scoring scheme, the more each card will be worth to a player who is investing in gathering that suit, and the less it will be worth to another player who isn’t. The higher this difference between value for a player who is collecting those types of cards and the player who isn’t, the less likely a player is to choose option 3 above, because getting stuck with a card of a suit you’re not collecting is very bad.

Victory point cost to veto – the higher it costs for a player to veto an opponent’s initial choice, the less likely a player is to veto, and consequently the less likely a player is to choose options 2 or 3 above, since in both of those cases the player has a high chance of getting left with something that isn’t their first choice.

Number of cards in hand – since players can sometimes play cards directly from their hands, the more cards a player has in her hand, the more likely she is to have a defined strategy that she doesn’t want to step outside of, so the less likely she is to choose option 3, above, and the more likely she is to choose option 4.

The core balance goal of this game is to make vetoing an attractive enough option that players must always take it into account, but not so attractive that players can always count on their first choice being vetoed. With that in mind, I can now apply Jaffee’s 5 steps for balancing game elements.

So next time you’re ready to balance a game, remember: when balancing, you don’t want your game elements to be “fair”** first and foremost. Your primary goal should be to make sure the numbers in your game work to afford the players with an interesting choice every turn and beyond.

Fairness is not usually bad, but it can get in the way of more important design, and it can definitely hurt when misused.

It’s worth noting that not all forms of fairness will result from my framework of balance as ensuring interesting player choice. For example, just making sure that players always have interesting choices doesn’t necessarily mean that going first won’t be a huge advantage. This is where fairness for its own sake can be taken into account.

篇目3,The Price of Personalization

by Josh Bycer

Personalization is one of the best ways of giving players progression and choices in games. Being able to create a character or army to the player’s specification allows them to connect more to their character and is a great motivational mechanic to keep people playing. Team Fortress 2 with its bevy of items is one of the best examples of providing replay-ability and longevity to a game. Because of the popularity of personalization, more designers are experimenting with it in their designs.

With Diablo 3, players can mix and match active and passive skills for each of the five classes, allowing two players using the same class, to be very different in terms of utility. While in Age of Empires Online, you can equip every build-able unit and structure with a variety of gear and take advisers into battle that provide age specific bonuses.

While all this looks great on paper, personalization needs to be kept in check as we’re seeing cases where designers are not able to see the forest for the trees with balance. To talk about game balance and personalization, there are two areas we need to focus on: single-player/cooperative, and competitive design.

The False Choice Syndrome:

Cooperative design is where designers like to give players a variety of choices, seeing as how they can design and balance them around player’s working together (or solo) instead of using them against each other. The problem which I talked about in my post about the difference between masochism and challenge in design: Is when to make a game difficult, the designers make some choices useless.

Diablo 3 is a different game when we look at the early to mid game (normal-nightmare) vs. the end game (inferno.) As it stands, many skills outright become ineffective for inferno, reducing survivability down to a number of pre-defined builds. Compounding this issue is that it’s hard to determine base-lines for enemy values due to Diablo 3′s system.

Because of how the primary attribute for each class dictates damage and defense, players who aren’t able to find loot related to it will have a huge disadvantage. But for people who use the auction house system, they can render the game a lot easier by just buying the best loot related to their class.

The problem is that there are so many permeations to a character, that it makes the end game near impossible to balance. They have 5 different classes with all the skills and runes, plus randomized loot for people who don’t use the auction system, and then they have to adjust for people who did use it. Blizzard didn’t just shoot themselves in the foot; they took a chainsaw and chopped it off.

In Demon’s Souls, game balance was far easier to achieve due to equipment placement and the leveling system. The designers had a good idea of what would be the base line attributes of a character at each stage of the game thanks to pre-defined equipment locations and altered enemy attributes accordingly. Of course, expert players who knew how to get every little bit of power out of their equipment and attributes could blaze through the game, but that’s alright. As balancing a game around the hardcore minority usually leads to boring design. This becomes even more challenging when you throw competition into the mix.

The Competitive Angle:

While balance is important for cooperative design, competitive games live or die based on how balanced they are. Gamers who play professionally will comb over every inch of the game’s design to find any little tricks or issues with the design for an advantage. If the game is not balanced, professional gamers will not touch it and the competitive scene will die.

The importance of balance is one of the main reasons behind the popularity of Starcraft on the professional scene. Not only did the designers balance 3 asymmetrical races, but they fine tuned them down to the decimal point of every unit’s attributes. Starcraft’s design is one of those games that deserve to be studied on this fact alone.

The detail that makes balance achievable in competitive games is a closed system. This means that there are no variables to the equation: a SCV in Starcraft will move and gather the same amount of minerals at the same rate every-time, no questions asked.

What happens is that when designers add the ability for the player to personalize their strategies, it adds variables to the equation. If any one of those variables leads to an always optimal strategy, a professional gamer will find it and exploit it until it is changed. For a game to be considered competitive, the gamers’ skill has to be first and foremost the factor in winning or losing. If someone can just equip better gear through time or money and can beat someone with several more hours at the game, no competitive gamer will want to play.

Strategy games in particular are easy to analyze due to how open they are in terms of numbers. The numbers game becomes an important learning tool for anyone who wants to be competitive at a strategy game. In Age of Empires Online the variety of items and premium upgrades that can personalize units is great, but they get in the way of providing balance.

Case in point: An Egyptian Spear-man can be upgraded to a champion via a premium upgrade. This upgrade not only increases the attributes of them, but removes the gold cost which is normally 10 per unit. What that means is that if someone researches it, after 15 spear-men the research has paid for itself. This is a huge deal and major advantage if two players are against each other and one hasn’t spent money on their civilization, then that player has a huge disadvantage.

With items, they can effectively break the balance of the game. Giving an archer unit enough defense and offense can make something that is only supposed to be effective against archers, now able to hurt everything. Combined with defense, even if another unit is strong against it, having 30% more health can be a huge deciding factor.

Imagine if players could choose special upgrades in Starcraft 2 before the match began: such as all Hydralisks have 0 vespane gas cost, and picture how bad the balance would be ruined with that.

Providing ways of personalizing the experience requires a careful eye for balance, and there are some tips designers can follow to prevent things from getting out of control.

1. An Open-Closed System:

Competitive games as mentioned require a set system for players to learn and build their strategies around. But that doesn’t mean a designer can’t give some leeway with variety.

In Command and Conquer Generals: Zero Hour, the expansion took the three playable sides: US, China and GLA and gave each one, three sub factions. Each sub faction took their respective side and altered it to emphasize a specific strategy. For example, the US air general removed the majority of tanks a player could build, but gave them more air units and made them cheaper in the process.

This gave gamers a chance to use these specific factions to alter their strategy during vs. but even though this introduced variety, the system was still closed as the player could not alter the sub factions. Recently Sins of A Solar Empire: Rebellion went a similar route, splitting each of the three races into 2 sub factions. Each one had different bonuses, units, researches and a super unit they could build.

2. A Variety of Limits:

Giving players multiple ways of affecting their character may lead to imbalance if left unchecked, but it can be reign in by providing limits. In Age of Empires 3, players had shipments in the form of resources, additional units, and upgrades that could be sent to their base during play. However, while the player can eventually unlock access to all of them through playing online, there is a limit of how many they can take into a match.

Because of that, it allowed players to create “decks” of different shipments built around different strategies for their civilization. Do you focus on the strengths of a civilization? Or work to counter their weakness? Or go for a jack of all trades route? No one could make their side unbeatable, as there weren’t enough slots available to fit every shipment in. Contrast to Age of Empires Online where players can equip everything with better gear. Meaning that the longer someone plays, the better their Civilization will naturally get.

3. A Side Order of Balance:

A discussion of personalization balance cannot be complete without another mention of Team Fortress 2. Valve has gone to great lengths to keep Team Fortress 2 as balanced as possible, even with more items then I can count. In the past there have been a few items that did slip through the cracks (the original medic hack saw upgrade for example,) but Valve has improved over time.

“Side-Grades” as they are called, provide unique bonuses to the classes, but they also come with a negative factor as well. From reduced damage, less ammo and many, many more are factored in to prevent any one item from being the optimal choice for all situations. The best part is that this prevents having more time spent playing Team Fortress 2, to beat out people with greater skill. It doesn’t matter what sniper rifle you’re using if you can’t aim accurately.

What’s important to remember is that for this to work properly, every item has to be a side-grade in some way or another. As having an item that beats everything else, defeats the purpose of the side-grade system.

Giving players more options of how to play the game always seems like a no-lose solution, but the more variations available, means more areas that need to be tested. If the developer wants to add more choices or even the option for PvP at a later date, they need to make sure that the foundation of the game is steady, or the whole thing could fall apart.

篇目4,GD Column 21: More Than Zero

by Soren Johnson

A zero-sum game is one in which the gains of any one player are balanced out by the losses of all the other players, such as winning a pot of chips after a hand of poker. Using strict game theory terminology, many competitive games are not actually zero-sum. Scoring a field goal in football, for example, does not take three points away from the other team.

However, more loosely speaking, the phrase “zero-sum mechanics” can mean that hurting one’s opponent is as equally valuable as helping oneself. In a typical RTS like StarCraft, a rush strategy, which aims to destroy the enemy’s economy as soon as possible, is just as viable as a boom strategy, which focuses on building up one’s own economy. If one can quickly wipe out the enemy’s first units, it’s irrelevant what level of development one’s own troops ever reach.

Thus, whenever a game rewards the player equally for hindering the enemy as for strengthening herself, the game has a zero-sum mechanic. Most team sports (basketball, soccer, football, etc.) share this characteristic; the defense, which prevents the opposition from scoring, is just as important as the offense, which does the scoring.

Competitive games are firmly rooted in this soil. Fighting games balance protecting one’s own health with taking away the health of the opponent. Strategy games encourage countering an enemy’s plans as well as perfecting one’s own. Shooters combine killing as many enemies as possible while also fulfilling some parallel goal, such as capturing a flag or checkpoint.

Zero-sum mechanics, in fact, seem to be the default choice when designing competitive games. However, their ubiquity masks the many, many problems with this type of gameplay. Indeed, zero-sum mechanics are, at best, a necessary evil and, at worst, a wrongheaded approach to game design that turns away many potential players.

The Zero Problem

The problem with zero-sum mechanics is that they require a negative experience for someone – watching a devastating combo annihilate one’s character in Street Fighter, watching one’s buildings crumble in Age of Empires, dying and respawning over and over again in Team Fortress. One player’s pleasure results from another player’s pain.

In fact, competitive games do not require that another player must suffer. A game’s rules determine the frequency and intensity of player interaction; ultimately, the designer decides how players will interact with each other during play. Indeed, competitive games are even possible without players being able to affect one another at all – consider parallel sports like golf or bowling, for example, or online games with asynchronous leaderboards like Bejewelled Blitz or Burnout Paradise.

The most important distinction is whether a player can lose their current progress or if they can only lose the ability to continue progressing. In the former case, the game mechanics have a zero-sum feel as losing one’s progress is usually a painful experience and often a sure route to a loss. In contrast, one of the defining traits of the Eurogame movement (epitomized by games like Ticket to Ride and Settlers of Catan) is eschewing such direct, zero-sum player conflict in favor of limited, indirect interaction which will not destroy a player’s progress.

For example, in worker placement Eurogames, such as Agricola and Caylus, players take turns choosing exclusive abilities; the competition emerges from players jockeying for position to determine who gets to grab the best jobs first. If a player knows his opponent needs food, choosing the food job for himself can seriously damage this opponent’s fortunes. However, this tactic is qualitatively different from actually destroying an enemy’s farms and killing his villagers in Age of Empires.

In the former case, the setback may only be temporary; in the latter, the player suffers a heavy emotional loss and has little chance of recovery. In fact, a player who spends too much time trying to disrupt his opponents in a game like Agricola can often dig his own hole as each precious action has significant opportunity costs. In contrast, damaging an opponent early in an RTS has little downside; wiping out another player’s economy can actually buy valuable time to grow one’s own much larger.

Balancing a RTS game to not reward destroying another player’s economic base as soon as possible is extremely hard. Indeed, RTS games suffer heavily from a dominance of zero-sum mechanics, which encourage the rush. Many players adopt “no-rushing” house rules to manually rebalance the gameplay away from destructive raids and towards building up for the endgame.

Further, many RTS games end with a whimper instead of a bang because the end goal is usually wiping out the enemy’s forces, which means that the outcome is obvious halfway through the match. In Ticket to Ride, during which players race to complete routes before running out of pieces, the dramatic tension is a consistently rising slope. In contrast, the dramatic tension of StarCraft is an arc which rises and then falls, and – unfortunately – the downward side of this arc is simply a sequence of painful events for the loser.

However, zero-sum mechanics need not be endemic to the RTS genre. Consider economic games, like the Anno series or Railroad Tycoon or even M.U.L.E., in which the primary goal is the acquisition of wealth; because the players are in a race to see who grows the fastest, the games need not encourage – or even allow – players to attack one another.

Alternate competitive mechanics are possible in military RTS games as well. Warcraft 3 introduced the creep – neutral characters who occupy the central area of skirmish maps and who players race to kill for the rewards and experience points. Perhaps a new RTS could take this mechanic a step further and make the game focus solely on killing creeps?

Removing the Negatives

Many competitive games solve the zero-sum problem by severely limiting interaction, so that players can only affect each other under certain circumstances. In Mario Kart, for example, racers can only shoot one another after picking up limited-use shells from certain locations; even then, players will only get the most powerful shells if they are trailing in the race. Even in a cutthroat RTS, a player can only attack after first building a barracks, then training troops, and finally moving them into position.

Thus, limiting player interaction is a powerful tool for minimizing negative emotions from zero-sum play. Games with similar themes and rules can dramatically change their feel depending on what sort of interaction is allowed. For example, Travian and Empires & Allies are similar asynchronous strategy games played over months of real-time about developing a military and then attacking one’s enemies. However, an important difference separates these two games with what happens when players invade each other’s cities.

In Travian, attacks are strictly zero-sum; resources captured by the attacker are taken from the defender’s stockpile. In Empires & Allies, however, combat is actually positive-sum; the resources captured by the attacker are conjured from nothing. Furthermore, while units which die in Travian are removed from the game, defending units in Empires always stay alive, even after a defeat.

Empires quietly belies players’ expectations for combat – that a victory requires a defeat – and this design choices pays off by making the game more accessible and less emotionally draining. In contrast, Travian uses the traditional approach that one player’s gain requires another player’s loss; accordingly, this design choice creates a nasty world full of brutish players with short tempers.

Many designers instinctively assume that conflict must be zero-sum, but this prejudice may be keeping their games from reaching a larger audience. The emotions players experience during a game are real enough, so a mechanic that requires at least some players to suffer should be used carefully.

Adding the Positives

Sometimes, alternate solutions are blindingly simple. In the board game 7 Wonders, players compete along multiple axises – earning victory points for science, civics, buildings, wealth, and military. The default way to implement military in such a game would be to allow players who invest in an army to attack other players’ units, buildings, or resources. 7 Wonders, however, employs a very different approach.

The game is split into three epochs, and at the end of each epoch, players with the largest armies receive positive points while the other players receive negative points. Furthermore, the total point distribution is actually positive-sum, so that losing combat does not hurt a player as much as winning combat helps. Thus, the military strategy does not drown out all the others and is appropriately balanced; a strong military cannot prevent an opponent from winning with strong technology because military victories do not require the loser to forfeit her progress.

Indeed, the spirit of positive-sum gameplay can benefit other aspects of game design. Puzzle Quest, for example, avoids a manual save system by ensuring every combat is positive-sum; players can never lose an item during combat and will always gain at least a little gold and experience from each battle. Thus, a player is always better off after combat, whether a win or a loss, so the game can constantly auto-save into a single slot. This feature, which would be hardcore if paired with a traditional zero-sum design, instead removes the need for a load/save system, which can be a barrier to entry for new players, thereby expanding the game’s potential reach.

Ultimately, zero-sum mechanics are still a powerful tool for game designers as they can unlock primal emotions. Sometimes, allowing players to destroy each other is exactly what a game needs. However, not all conflict need be zero-sum, especially since that design choice has significant disadvantages. Losers need not suffer so that winners can triumph.

篇目5,Richard Garfield’s strategies for game balancing

by Leigh Alexander

This weekend at New York University, an intimate audience had the opportunity to hear game balancing strategies from a master — veteran designer and Magic the Gathering creator Richard Garfield.

PRACTICE at New York University’s Game Center is a now-annual observance of game design as art and practice — a conference focused on the moment-to-moment experience of game design, and on building a community that supports game design as a process in culture.

Garfield may be one of the most prolific and influential living designers, responsible for countless physical games that have influenced design and business models. Yet balance is an ambitious topic, even for him.

Given the breadth of variety in games, it’s challenging to talk generally about them. “An analogy you might draw is that if you’re a biologist and you’re talking about life, there’s a crazy amount of life,” he says. “It helps to take a subset of that and say, ‘I’m going to talk about that.’”

Balance in orthogames

For the purposes of his discussion Garfield chooses to focus on orthogames, which he defines as finite multiplayer games (two or more players) that result in players being ranked — classic games like bridge and chess fall under this umbrella, while FarmVille doesn’t.

“We define balance as strategic collapse,” Garfield explains. “What this means is that games can be approached with a set of strategies and if there’s a strategy that is regarded as not being viable that people think should be viable, then people will talk about this as not being balanced.”

Strategic collapse occurs when one strategy is so preferable that all players essentially choose it all the time. In the Magic tournament environment, looking for a variety of deck types is a good way to check the health of the tournament. A wider variety of types keeps the game balanced, and it’s less enjoyable when there’s perceived to be just one viable deck type. On the other hand, too many deck types is too confusing for most players.

“There definitely can be too many strategies,” Garfield says.

Sometimes strategic collapse has nothing to do with strategy at all. For example, the player that goes first in Tic-Tac-Toe will win much more frequently, such that an opponent might lose interest in playing the game simply by virtue of not going first.

Garfield also highlighted the concept of play style collapse, relevant to balance — players all approach a game in different ways, and a game that has weaker support for your approach than for other approaches will feel unbalanced to you.

Two ways of viewing balance

He views two types of balance: Holistic and componential. When a game has separate components that need to be balanced, it’s componential — in Magic, should a lightning bolt cost just one red mana? In Diablo, should a piece of equipment give you 152 intelligence? Holistic balance issues concern the game as a whole — in Magic should you start with 20 life or seven cards? In Diablo, should you be able to sell equipment for real money?

Sometimes the distinction is muddy, he notes, but it’s still useful in talking about balance to differentiate.

“Often designers will design the game to be balanced for the expert,” Garfield says. “This is certainly the way we thought about it in the early days of Magic, and it took me a while to outgrow this mode of thought.”

A game balanced to favor experts risks other types of gamers having an unbalanced experience — and the game may lose most of its players before they ever develop the skill level to attain the well-balanced experience. Meanwhile the experts run out of people to play with.

Also, balancing for experts often fails to consider that there might be levels of proficiency even above what the game is desgned to contain. Designers aren’t necessarily the best players — most of the time, they’re not, actually.

All kinds of games are patched with rules to accommodate players that outgrow their bounds. Balancing is helped by the fact that most of the time skill goes up logarithmically, and the benefit for performance tapers.

The important thing is to provide options so that every type of player has a good choice, versus grouping players into correct and incorrect ways to use skills or classes. This lets players compete even if they’re not mechanically-focused — like roleplayers or fans of storytelling.

Some of these players will choose gear for their character based on appearance or narrative suitability, and feel forced out of their play style by the fact that other players are more successful. That unbalances their experience.

Strategies for balancing

“Balance is an art, not a science,” Garfield says. Math helps in his game design, but never supersedes the level of complexity that a poker player would need to know.

“I came to the conclusion there is just no formula,” he says. “If you haven’t solved the game, it seems a tall order to actually come up with a formula to balance the game in the sense that people usually mean… and balance is different for different audiences. If you solve the game and then balance it, then you’re only balancing for the expert, which we’ve established you don’t always want to do.”

And audiences are always changing: Beginners become intermediates become experts, younger players become older players. “It’s a moving target,”” he says. “Because of all this it’s really a matter of psychology, rather than math, so you shouldn’t expect there to be an exact formula.”

An iterative design approach with a lot of testing and flexible prototypes is one essential technique to find a game’s natural balance — Magic was playtested for two years. “I have tried many, many times to design games as a document… but it is really hard to internalize what the game is going to be like unless it’s really closely modeled on a game you already understand.”

One benefit of iterative design is that everyone is a beginner at first, and the scope broadens as development goes on. But a risk is that the more you test and iterate, you can lose track of your beginners and casual players — so intentionally bring in new people regularly and ensure you have a good mix of players familiar with the game and people who know little about it.

These days, publishers are likely to iterate after a game launches — which is fine provided it launches with enough balance for beginners and can rebalance fast enough to keep up with the growing player base and not lock out new players either.

Rock-paper-scissors

Rock-paper-scissors’ structure — where every element of a game is strong against a different element — is incredibly helpful to keep in mind while balancing, Garfield says. On the component level it appears in a broad range of games, from Stratego to Team Fortress 2. On the holistic level it works too — take rush, defense and economic-oriented gameplay patterns for Starcraft, where each strategy is weak to one other strategy.

“Once that was recognized by Blizzard as being a healthy rock-paper-scissors relationship, it’s designed with that in mind,” Garfield points out. “If they make units or base states for the game which imbalances that and makes one of those strategies dominate the other, then they will tweak those back.”

While rock-paper-scissors in itself can be regarded as a trivial game, there’re options: Rock doesn’t need to beat scissors 100 percent of the time, for example. As long as the odds are better than 50 percent, then the structure is sound, and in fact in many cases it’s best to make it so that the entire game doesn’t rest on a single choice. Choosing a strategy within a cycle simply improves the success chances of a player that prefers that strategy, rather than guarantees a victory.

Add cost

Another useful idea for balancing is to generate and define a “cost” for components that need balances, where that cost can be multiple resources. The cost can be paid during the course of the game, and all players begin at the same base. If the game has in-session costs and between-session costs, they usually will be a different resource and sometimes the cost will be difficult to define or subtle.

“The important thing is that you have one, or perhaps a few numbers to tweak to balance your components,” Garfield says. “With cost and score [you need] one number that your developers recognize as being the principal knob. And as you become better at understanding your system… you’ll become experts at tweaking that knob. In Magic, once we got good at tweaking the mana cost knob, we got better at tweaking other knobs.”

Non-domination

Start by setting a series of benchmarks for cost. After that, grow the system — add new components in such a way that new ones don’t dominate the old ones by being strictly better, he advises. With domination things are easy to value and thus games have less dimension; non-domination generally offers a wider array of viable choices.

If a component is too powerful, you can use a strategy or component that “hoses” it, or reduces its efficacy. Magic uses this a lot; for example, the hurricane card damages all players and specifically flyers; “if I’m running into problems with my opponents playing a lot of flyers, here’s an answer. Now if they rely too much on flyers, I will beat them.” Starcraft’s observers hose invisibility. Adding a hoser creates a viable response for players to use against specific strategies or powerful components.

Often, hosers can create a rock-paper-scissors situation, where Strategy A is the ideal choice against Strategy B but is vulnerable to being hosed by Strategy C.

Players can also bid for access to elements and features as a method of controlling their growth arc and keeping balance intact. Sometimes variance also assists in balance — a strategy that isn’t viable most of the time may randomly become viable. This is often present in card games. To mitigate a very powerful approach, make that approach useful under rare circumstances.

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号