万字长文,关于游戏趣味性起源和构成的相关探讨,中篇

篇目1,从七个角度阐述游戏的趣味性构成要素

游戏化是人们最近热议的话题,圈内许多人士都在讨论游戏化与游戏体验之间的相似性。

我对这种讨论持有两种观点:

1.“游戏化”这个词汇带有机会主义色彩,并且定义模糊。它看似包揽了游戏的所有优点,但其实际作用目前仅停留在积分和徽章奖励这个表面上——例如忠诚及名望系统。

2.游戏的意义极为丰富,当前游戏化形式的起步并不算糟糕。将忠诚及名望系统与网站或产品绑定的做法已不鲜见,相信游戏玩法的其他元素也将接踵而至。

在这里,我想为游戏趣味性的“结构”下定义,并探索这些元素应用于现实商业的可行操作方法。本文将主要剖析游戏、有趣、玩这三个概念之间的交集。

游戏为何具有趣味性?

不少学者和游戏设计师都曾探讨过这个问题,游戏设计界对此问题的普遍回答是:游戏让玩家选择和学习。先来看看一些游戏行业元老的观点:

Raph Koster在《A Theory of Fun》中指出:

趣味性就是大脑处理问题的活动。

Jesse Schell在《The Art of Game Design》的看法则是:

游戏就是人们通过的玩乐的心态解决问题的活动。

我完全同意这二位的说法。我自己也做过几乎相同的定义:(趣味性就是)有趣的决策(Sid Meier也说过同样的话)。我下此结论的原因是,我个人很喜欢游戏中的“决策”和“ 挑战”元素。

如果你是为像我、Raph和Jesse这类人设计游戏,这种定义应该十分管用。电子游戏设计已经有30多年的发展史,假如你的工作是解析游戏,并在企业网站等全新领域中重新运用“ 趣味”元素,那么深入理解其定义必将为你派上大用场。

出人意料的事实

我们看到有不少游戏正逐渐丧失其教育性,《FarmVille》和Foursquare尽管其中所涉决策有点无趣,可供人学习的知识极少,但仍然被称为“游戏”。如此看来,通过“选择”和 “解决方案”来定义游戏似乎有些片面。

但也有一个观点可支持原来的定义。《FarmVille》当中还是有一些可让人学习的元素。至于Foursaquare,我想人们从中学到的通常就是在哪能保住自己的市长头衔,在哪会失去 这顶“乌纱帽”……

但我并不是在为游戏的旧定义背书。事实上,我认为这些“游戏”中的学习层面太肤浅,几乎不能算是具有教育性。就算你假设《FarmVille》玩家的智商略低于一般的“真正游戏 ”玩家,那也不能解释他们长期逗留游戏的原因——他们是持续数月泡在游戏中,这么长的一段时间早就足够傻子学会游戏中的一切操作和活动。

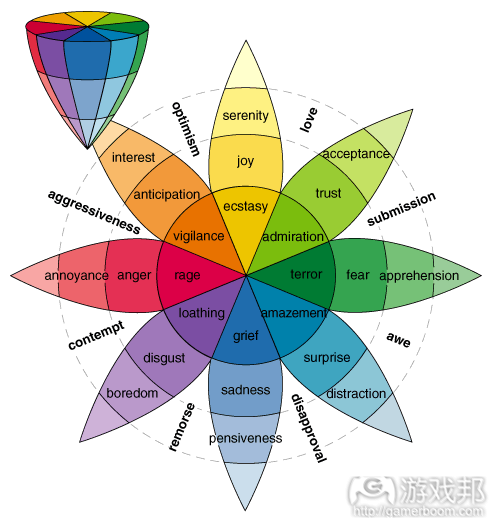

Plutchik-emotion model(from gamasutra)

我们其实只有两种选择:要不就否认它们属于“游戏”范畴,要不就承认游戏的意义远甚于传授知识。

在深入讨论这个话题之前,我们也许可以再给旧定义一个辩驳的机会。Schell和Koster并没有说游戏只是传授知识,他们称游戏是以“玩乐”或“好玩”的心态学习新事物。Raph 的解释如下:

趣味性与情境有关。我们融入一项活动的原因极为重要。

所以,有趣游戏的定义并不仅局限于学习知识,但Koster和Schell两者都无法用一句话简要概况游戏趣味性的定义。看来,“有趣”确实是一个非常微妙的词语。

哪些元素构成了游戏趣味性?

正如上文所述,游戏设计师已有自己的答案,那就是游戏趣味性的要素之一:学习。我认为这确实是一个恰当的说法,有些游戏的趣味性几乎完全围绕“学习”而设计,例如《魔 术方块》(Rubik’s Cube)和《珠玑妙算》(Mastermind)。

我想设计师对此话题还有其他高论,但为了节省时间,现在得轮到学术界发表观点。

如果你看过Salen和Zimmerman的《Rules of Play》,那就应该听说过社会学家Roger Caillois对四种玩游戏形式的看法:

竞争、机会、角色扮演和改变观感。

虽然Caillois是社会学家而非游戏设计师,其总结的四种玩游戏形式看似过于随意,但我们仍然不得不佩服他能够在不同角度下此定义。我认为他的观点颇具独创性。

竞争很显然属于趣味性范畴,从晒出外州车牌照到与他人比赛快速挖煤,几乎每一项具备这种特点的活动都可以转变为游戏。

角色扮演也很显然属于此列——我们还能用其他词语来解释孩子们玩过家家、模仿消防员等此类行为和活动吗?

改变观感可能是Caillois最有趣的提议了。

电子游戏中偶尔也会出现这种情况(游戏邦注:有些游戏通过曲扭规则来“迷惑”玩家,有些游戏则以光影和音效创造一种令玩家产生“幻觉”的体验),但虽然我很想把它添加 到我们的趣味性元素列表中,但从总体上来看,改变观感应用范围有限,在商业项目中尤其如此,所以我们将跳过并忽略此项。

最后就是机会。机会是一个可望改变既定结果的机制。两名技能并在同一水准的玩家如果在一款缺乏机会的游戏中相遇,那就很容易在游戏开始之初辨出胜负。机会对保证游戏 平衡性和产生悬念来说十分重要,但并不一定具有趣味性,也并非玩游戏的必要前提。

游戏设计师Marc LeBlanc所列出的元素比Caillois更详细和实用,尽管从他的职业来看我应该将其划分到上文的内容中,但我发现他的工作更适合从学术角度发表观点(游戏邦注 :Marc LeBlanc与美国西北大学的学者合作甚密)。

LeBlanc认为游戏趣味性具有8要素:

感觉、友谊、幻想、叙事、挑战、探索、表现和服从。

感觉包括坐着过山车在半空盘旋呼啸的刺激感,跑步者的兴奋感,或者按摩时的舒适感,但在游戏化环境中,它的应用甚至比改变感观还少。

友谊要涉及社交层面的概念,它与友好和归属感有关。我们很难找到一款完全以友谊为支柱的游戏,但许多人就是因为这一点而喜欢玩派对游戏。

举例来说,我发现《Apples to Apples》是一款傻气十足的游戏——它的赢家是随机选择的,但我还是喜欢玩这款游戏。为什么?因为我发现自己会忽略其中的竞争和学习元素, 总是沉浸于社交互动和众人欢笑之中。对我来说,友谊就是我玩这款游戏的唯一原因。

幻想和叙事彼此相关但又十分相似(我认为它们分别描述了游戏故事的前提和过程),我不知道是否有人会将故事称为游戏,但从营火会故事或卧谈会故事来看,我们总会不禁发 现幻想和叙事的相似性,或者至少会承认它们存在乐趣。

许多游戏都包含故事元素,我甚至还听说有人只是为了知道故事结局而玩游戏。我认为凭这一点已经足够将这两者纳入趣味元素列表中了。

挑战和探索正是Koster和Schell已经提到的元素,所以它们毫无疑问当属此列。

表现与角色扮演十分相似,具有许多共同特征。

服从这个词听起来让人颇为不悦。LeBlanc将服从定义为“无意识地玩游戏”,尽管它似乎也应该纳入我们的列表,但它却并不具有任何教育性。如果它也算是有趣,那么凌晨3点 的电视广告也很有趣,那我想大家就会觉得我们对趣味性的定义过于广泛了。

所以在Marc的8个要素中,我们只撷取其中的6个。

下面我要介绍的一位学者是Nicole Lazzaro,她的研究范围包括我们前面谈到的“选择”和“挑战”,但她主要关注游戏玩家的情感和心理研究。

在她看来:

调查结果表明人们多数时候是为了游戏所创造的体验(例如:肾上腺素兴奋,错位的冒险经历,脑力挑战),或者游戏构造提供独处或好友陪伴等因素而玩游戏。

她看起来是从情感角度来研究游戏(游戏邦注:作者认为这种研究角度的实用性存在疑问),但也确实提出了一个有价值的观点:纯粹的情感因素在“有趣”概念中占有重要地位 。

人们究竟为什么要看恐怖电影,与伴侣调情,相互恶作剧?因为他们发现这些活动可以强化恐惧感,激励感、幽默感、悬念和意外感。

说到这里,我要再介绍一位可能好像从未与这些话题沾边的学者Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi,他是我们所知的心流理论专家。在他看来,所谓“心流”就是:

当人们完全沉浸于某项活动中时,就会丧失时间感。在这种状态下,人们的每一个动作,每一步行动和想法都与前者流畅衔接在一起,就像玩爵士乐一样。

人们常把心流状态用于描述“平衡的难度”,或者将其视为另一种心理状态而忽略它。我认为这个话题比以上的任何一种解释都要有趣得多,它当然也应该纳入我们的趣味元素列 表中。如果要说明哪些心流状态可以称为“游戏”,我可能会以重复将球弹向墙壁的现象为例。尽管此类活动也包含学习技能的要素,不过我认为这种技能并无价值,也许应该包 含更多有意义的内容。

总结

综上所述,我们现在可以整理出一份构成游戏趣味性的元素列表:

1.学习/挑战/探索

2.角色扮演/表达

3.竞争

4.友谊

5.幻想/叙事

6.情感

7.心流

以下则是我根据自己的看法进行调整后的简化版列表:

1.发展

2.选择

3.竞争

4.身份

5.故事

6.情感

7.心流

我认为如果还有其他什么需要添加的元素,也都可以归入以上7个要点的范畴。

假如我们将“游戏”一词定义为:为寻找乐趣而进行的一种活动,我想这更有助于推进我们对游戏化的分析和研究。

我将在之后的文章中对以上各个元素进行说明,解释它们独立存在时会发生的情况,以及它们运用于传统游戏领域中的情形。

简化列表元素的原因

我们在文章开篇已经提到了三个概念:学习、挑战和探索。这里我还要添加第4个概念:成长。成长意味着超越原来的水准,向更高更好的方向前进。

我之所以更情愿使用“成长”一词,原因在于比起其他三个概念,它更为直接地切入重点:我可能学习了一些东西,但却并不感觉自己在朝有用的方向进步;我可能在进行挑战, 但却讨厌那些不必要或无意义的障碍;我可能探索到了些东西,但却发现它们毫无意义。只有发展这个概念同时准确地表达了一种个人发展和积极体验的状态。

Role Playing(from hitesh.in)

如果你将故事(它包括幻想和叙事)的概念忽略不计,就会发现角色扮演和表现这两者十分相似。它们都可以提供一种让你无拘无束,表达自我主张和新价值观的机会。这似乎又 贯穿了两种元素:身份和选择。身份很重要,但它实际上在本列表其他元素中已无所不在(如下文),因此不再赘述其意义。由此可见,选择,或称为自主权确实该在本列表中占 据一席之地的元素。

友谊是一个很有趣的词语,我们这里指的是一种归属感——即在一个社会环境中的角色或地位。没有哪一个词比身份更适合形容它。我知道自己是谁,其他所有人也都知道这一点 。虽然友谊通常暗指一种纯粹的朋友社交关系,但又不能用友情这个过于准确的词取代它——毕竟几乎所有人都追求一种身份感,但大家却不一定都喜欢与人打成一片。

至于幻想/叙事,我之前已经提到,这两者分别描述了故事发生的前提和过程。“叙事”可能更易同时概括这两种状态,但若要用于表达拥有趣味性的故事,却不免显得过于正式和 冷漠。用户都喜欢称为“故事”,而我也觉得这个描述确实更有深意。

成长描述的是一种拥有方向和前进的感觉。它是人类的一项基本内容,我们长大成人的首要挑战,中年危机的普遍来源。你问小孩他们长大后想干什么,相当于是在问他们的未来 规划,人生方向。等到你步入暮年之时,回顾自己的过去,就会因自己的成就而获得满足感。这些成就始于何时,终于何处?当我们之前所谈的理想都一一实现时,我们的整个人 生就可以归纳为一个成长的故事。

成长类型

孩子

对孩子们来说,成长包括身体上的生长,他们逐渐获得成人特权和承担责任,发展为“健全”而有用的成人。

成人

那么孩子长大成人之后呢?成长这个词的定义在这里又有什么变化?对成人而言,成长究竟有何含义?

孩子在年幼之时,就已经通过其他形式补充自己的实体成长过程——例如扩展知识面,取得一系列成就,逐步掌握相关秩序,建立好友人脉。在身体停止成长的时候,我们就了解 了基本的社会规则,这种对生活其他层面的追求将引导我们度过余生。

从许多方面来看,这些其他形式的成长不但创造了个人追求的动机,而且还是构筑社会的基石。我们对学习的渴望有助于解决问题,追求竞争可让我们超越自我并找到最优策略, 对秩序的渴望促使我们采取维持和保护行动,而人际交往则让我们彼此紧密联系在一起。

多数人都不会分门别类地记录自己的成就,而我们也确实还没有衡量成就的通用标准,但我相信自己列举的四种方法极具普适性,我认为基本的成人成长类型包括:

·学习

·秩序

·克服挑战

·人际关系

这四种成长类型让我想起Bartle玩家类型、Myers-Briggs人格类型等其他人格分类系统。这些人格分类系统能否指出不同人所追求的成长类型?

尽管这种分类法有助于我们了解不同人的差异,但从属性和原型来看,这种分类法可能存在一定导误性(例如,以甲壳虫乐队为例,使其四个成员对号入座)。若从属性层面上看 ,我们确实清楚这种分类法只是针对个体的差异性而言,但如果考虑到动机因素,它很容易让人误以为这些“类型”适用于所有人。换句话说,每个个体都有可能比其他人更明显 具备某项特征,不过从一定角度上来讲,这些分类对所有人来说都有一定参照价值。

不同情境下的四种成长类型

学习。学习来自对规则系统的理解。通常而言,这相当于一种反复试验的过程:先是形成假设,然后在游戏环境中对其进行试验。

以《街头霸王2》为例,玩家首先要学习如何移动,然后才会发现有效的连击动作,最后就是找到使用这些策略的最佳时机。

虽然学习的目的是让人们得到竞争优势,但其本身也可以令人愉快,让人乐在其中。为何桥牌游戏如此受欢迎?这是不是与它总能让人获得更多学习的乐趣有关?

秩序。这个词看似一种奇怪的成长定义,但我认为如果从规则的角度来看,我们更容易理解其含义。

人们通常都相信生活有其内在意义,而实现这一目标就要求社会存在某些隐性规则——正确概念及错误行为。从个人发展层面来看,秩序代表人们走正道的追求。

在多数电子游戏中,追求秩序的动机产生于因遵守规则而得到奖励,例如收集道具,完成任务和晋级。那些追求秩序的玩家喜欢体验规则明确,并且以遵守规则为获胜条件的游戏 。他们希望系统运行有规律,带领他们向更高级的目标或状态前进。

克服挑战。有人推崇秩序,也有人追求混乱。生活时时充满挑战,人类必须学会应对逆境以获得生存。虽然这种过程很刺激,但也可能很痛苦和让人不快。在现实生活中,有许多 无法克服的挑战最后总是让我们很受挫。

而游戏所提供的总是我们能够克服的挑战,若非如此,其设计必定存在严重的问题。但平衡这种挑战性却并非易事:游戏太容易就会失去挑战性,太困难就会让人受挫。挑战型的 玩家需要的是一种挑战和胜利的良性循环。

人际交往。正如多恩(游戏邦注:英国16世纪神学家兼诗人)所言,没有谁能像一座孤岛一样在大海里独踞。与他人交往和联络感情的需求深深扎根于我们生活的方方面面,这种 需求是人类文明和社会的基础。

在游戏中,社交成长主要体现为相互依赖——有人需要你的帮助,你也离不开他人。从《魔兽世界》中的公会到《CityVille》中的交换礼物等现象均可以看出,双方的这种依赖性 越深,就越能够让社交型玩家获得许多回报。

在设计中植入成长机制

为了研究如何将成长植入非游戏环境,我们要先谈谈每种成长类型的适用情境。

植入学习机制。学习需要一套规则系统,任何系统都能满足这个条件,但很显然,规则越是微妙和精细,就越能支撑长期的学习机制。

但不幸的是,我们还要考虑学习曲线这个额外的复杂因素。不同玩家的学习进度不一样,如果不想让游戏流失用户,就必须提供富有弹性的学习机制。理想的学习曲线应该提供简 单的交互层,但同时又具备深度发展的空间(游戏邦注:这里指策略、规则变化等)。

总体上看,你不需要为添加学习机制而设计游戏,而是要用设计来管理游戏已经具备的学习机制。要简化必要的学习机制,同时为更高级的用户设置具有一定难度的“终极游戏” 目标。

另外,挑战性和游戏中的琐事如果处理得当,也可以具有娱乐性并辅助学习过程。

植入秩序元素。秩序正是将徽章、奖杯以及当前的“游戏化”概念,把游戏与非游戏体验衔接起来的元素。基于徽章的系统并非新鲜事物,小孩因提交家庭作业而获得金星,军官 接受别在肩上的臂章,这些奖励都具有相同的属性。

为强化其意义,我们可以用象征性的符号来纪念重要经历,而微章又可与奖励或特权相联系。例如,金星也许可以让孩子获得糖果奖励,而臂章可以提高军官等级,增加他们掌握 的实权。

植入克服挑战系统。我们在这里所讲述的是战胜敌对势力。玩家希望体会到强大和重要之感,他们希望自己的成就独特非凡。

但从实际逻辑上看,大家都知道让所有人都与众不同是不可的。在单人游戏体验中,玩家的个人表现没有其他参照标准,这并不是什么问题,因为这类游戏并不一定要体现胜利 的大小。只要让游戏充满挑战性即可,没有人会质疑这一点。

我认为比起其他元素,这种克服挑战的系统正是传统电子游戏延续至今的主要趣味所在。

在社交环境中,玩家可以比较游戏进程,他们不会过于重视成就的大小。假如我完成了一项艰难的挑战,结果却发现多数人更省时省力地取得了同样的成绩,那么我获得成就的趣 味感可能就会因此而荡然无存。

为了维持玩家的胜利感,我们设计游戏时需要采取更复杂的策略。例如定制多种胜利结果,或者简单地避开这个问题,让参与竞争的双手都误认为自己赢了(游戏邦注:作者认为 《Empires and Allies》就是这方面的典型)。

如果这种欺骗性的做法不受欢迎,那么最佳选择可能就是将单人体验和社交挑战结合在一起,利用许多非竞争性的胜利元素吸引玩家,将他们引向更有难度、更具社交挑战性的胜 利顶点。最具竞争意识的成就型玩家一般都喜欢追求远大的目标。

植入社交成长意识。促进玩家的社交成长需要满足一些条件。首先,游戏中要有能够让玩家交流与合作的场所。如果玩家不能以富有意义的方式彼此交谈和互动,他们就不可能产 生社交联系。

其次,游戏中要创造特定语境,社交目标或者至少一个对话起点。

第三,这种社交成长必须具有持续性。要支持玩家反复联系相同的人。

Facebook等社交网络可谓将这三个要素诠释得淋漓尽致,涂鸦墙贴子、消息、标签和评论等构成了用户交流的场所,状态更新和分享功能创造了交流的语境,而社交网络本身就是 保持联系的体现。

内在激励因素

情感是一个含义模糊的话题,在定义其趣味构成之前,我们有必要进一步探讨其意义。

笛卡尔(法国数学家、哲学家)、霍布斯(英国哲学家)等哲人早已列出“主要”的情感类型,这些情感列表基本上各有特点。

情感领域的思想家Robert Plutchik制作了一个具有8个点,4个组合的模型:愤怒–恐惧,期望–意外,快乐–悲伤,欣赏–厌恶。

James Russell则提出了一个更具逻辑性的模型,他绘制的二维图表中分布着8种情感,纵轴是觉醒–沉睡,横轴是快乐–痛苦。兴奋、满足、沮丧、悲伤则顺时针分布于这四个象 限之间。

Russell这个模型将所有情感纳入觉醒–沉睡,快乐–痛苦的范畴,可以算是一个较有衡量性的系统。

虽然我不认为Russell的这个模型有何问题,但它所描述的情感类型却并非我们研究的方向。Russell所归纳的是较为原始的,连爬虫动物都有的情感,但它并不能解释政治讽刺文 学或惊悚小说的魅力所在。

自人类载史以来,我们认为有趣的内容几乎都有个一致的模板:体裁。有趣的是,多数体裁都会与特定的情感挂钩,例如悬念、爱情、喜剧、恐怖、历险、戏剧和悲剧。尽管这并 没有全面覆盖人类情感类型,但它确实已包含我们所述的与娱乐相关的所有情感。

与娱乐相关的情感

游戏设计经常把多种情感交织成复杂的故事,但为了便于理解,我们将使用最简单的例子对这些情感逐个进行解析。

悬念(或惊悚)或许是游戏中最常见的情感类型,此类游戏通常会设置未知的结果。完全采用悬念元素的游戏包括《Water-balloon Toss》、《Crocodile Dentist》和《Don’t Wake Daddy》。

除此之外,带有紧张感的游戏通常也包含悬念元素,例如儿童在暗室所玩的捉迷藏游戏、纸牌游戏Slap-Jack以及恐怖生存游戏(这些游戏中常有一些怪物冷不防地从玩家毫无防备 的方向跳出来)。

爱情也常与悬念相联系。这方面的例子包括日本恋爱模拟游戏《神秘约会》,转瓶游戏和脱衣扑克。有些人可能会认为调情和约会是配对游戏中的一个环节,我认为在线社交游戏 中的性紧张现象也可以划入这个范畴(例如《Zynga Poker》中就有许多用户调情行为)。

喜剧是《Taboo》、《Once Upon a Time》、《Balderdash》和《Apples to Apples》等许多创意派对游戏的主要目标。《Balderdash》和《Apples to Apples》这两者甚至还通过 投票机制奖励那些最搞笑的玩家。

但这些游戏的规则中却并不含喜剧元素,只有当玩家在特定语境下自由表达时才可能会碰撞出喜剧的火花。另外,你在Facebook涂鸦墙上也经常可以看到好友的妙语和小笑话。

恐惧作为一种娱乐元素时,通常得能够让用户产生恶心和害怕之感。恐怖游戏通常从包装和名称中就能体现出来,例如FEAR》、《生化危机》、《生化奇兵》和《死亡空间》。

冒险元素贯穿于每款拥有一个故事主角的游戏。玩家在冒险游戏中要战胜逆境,逃脱死亡,争分夺秒。从许多方面来看,冒险题材的游戏通常也涉及其他多种情感,带有一点惊悚 、恐怖、喜剧、悬念甚至爱情元素。但它对这些情感的涉猎并不深,也许正是这种平衡性让冒险游戏拥有如此魅力,并且难以被其他简单的非游戏体验所复制。

戏剧是一个含义广泛的词。戏剧还包含一系列上文未曾提及的情感,例如嫉妒、怀疑、恐惧、内疚、野心、厌倦和抑郁等。

游戏的故事情节也常运用戏剧元素(JRPG游戏最为典型),但在实际玩法中,游戏会更侧重怀疑和野心等竞争性层面。多人游戏通常会对竞争和协作的平衡性提出要求,《Avalon Hill’s Diplomacy》就是巧妙结合信任、恐惧和内疚等戏剧元素的少数典型代表之一。

悲剧看起来像是最不具有代表性的情感类型,只有少数游戏会专门采用这种元素(游戏邦注:例如《旺达与巨像》和《剑与魔杖》,这两者都采用微妙的悲剧元素)。

为了制造悲剧,游戏必须具有失败的结局,但失败并非多数游戏设计所考虑的选择。

情感是一种难以植入游戏中的元素,除了在传统的游戏叙事方式中发挥作用,它通常并非游戏设计所追求的明确目标。如果要将情感作为游戏玩法的目标,我认为可以参考以下三 种游戏设计中的情感归类方式:

悬念——最适合传统游戏机制

爱情、喜剧、戏剧——如果考虑周全,在游戏设计中会很管用

恐怖、冒险、悲剧——仅适合含有故事元素的情境

选择

“选择”一词可以定义为策略性选项或战术风险,我们在讨论成长、学习与克服挑战时已经涉及这两个话题,现在我想讨论的定义则是:自由选择与自由行动。换句话说,也就是 自主权。

许多现代文明都是构建于自主权是与生俱来的权利这个概念,我们可以将这个概念称为:自主、自由和表达。我认为每个自主性的选择都包括三个因素:冲动、影响和道德。即对 推动变化的渴望,这种变化所产生的后果,以及这些后果的道德含义。

我要重申的是,这些并非我们做出选择时缺一不可的考虑因素,但至少需要满足其中一者(假如三者俱无,那么这就是一种随机性的举动,根本算不上是一种选择)。

冲动

也就是随心而欲。冲动是人类精神的一个基本元素。例如,我想得到什么就拿什么。我觉得某些东西应该是什么状态,就采取行动令其如己所愿。尽管如此,我们还是不能完全让 冲动来支配自己的行动。

事实上,我们其实无法满足自己的大多数心理冲动。因为我们知道一些行动的后果,以及不计后果会带来的风险,所以我们会克制自己的行为。但这种自律心理有时会让我们纠结 和烦恼。我们很想表达自己的意愿,尽情地做自己想做的事情。人们谈到“无拘无束”一词时,基本上是指放下一切束缚、规矩和限制——通过躲藏到自己的小巢、进行远足或者 玩电子游戏等安全的地方,满足自己的一部分小冲动心理。

影响

简单地说,影响就是指每项行动的结果。每一个选择也必然会伴生一个结果。从冲动的角度来看,这两者的因果关系非常明了,例如,我选择草莓酱的原因是它的味道比葡萄更好 。

但对于长期影响来说,它可能是一种可深刻改变人生的重大影响:我选择在洛杉矶攻读计算机科学,这个选择直接影响了我后来遇到的人、我去的地方和我的所做所为等人生事件 。

值得一提的是,这些选择并不只是影响了我们本身,它们还影响了他人以及我们所处的环境。假如我们的存在不会带来任何影响,那么我们所扮演的角色及我们本身的存在意义就 很成问题。

如果我的行为不会对社会造成任何影响,我又何须降临人世?

我们可以将影响划分为三个不同层面:

自身:这是影响的基本层面,深受西方文化影响的人通常认为,自己的命运应该对世界产生一定影响。这是人们的一个主要期望,其中还包含一定的责任感(我要对发生在自己身 上的事情负责)。假如我爬上屋顶并不慎摔了下来,我就得处理自己受伤的事情。

环境:这是影响的下一个层面,人们常觉得自己应该对周围环境施加影响——改变周围环境的条件。这是人们的第二个期望,其中也包含适度的责任感(我是环境的一分子,我的 行为会对这个空间的未来资源产生影响)。假如我搞坏了屋顶,我就得修复它,以免屋顶漏雨。

他人:在第三个层面,许多人都希望自己能对他们产生影响,这是人们的第三个期望,并且带有高度的责任感(我会对他人遇到的事情产生影响)。假如我让某人爬上屋顶,对方 摔下来受伤了,我可能就要为此负责。

道德

自主选择的第三个因素就是道德。它意味着我们所做出的许多决定包含公众普遍认知的正确与错误选项。因为道德准则是由社会而定,其中难免有一些原则与个人本意相悖。

当个人意愿与社会追求并不一致时,道德准则就成了我们采取行动的唯一选择。个人究竟该遵循自己的冲动,还是社会诫律?前者可以让个人得到好处,而后者则是社会认可的行 为。

在强大的社会体系中,人们常因慑于惩罚而做出道德选择。在害怕惩罚的个人看来,真正意义上的的道德选择可能仅局限于一些琐碎的事情。例如,我可能会有闯红灯(较小的缺 德行为)这种行为,但却从不会考虑去杀人(这是极大的违法行为)。

这里我们谈到了法律,而法律则代表社会对个人选择的最基本影响。社会的影响还包括其他形式,例如较不正式的规则,体统、骑士精神、尊重和礼貌。这些都是一种道德选择形 式,都是社会制定的标准。这些规则并不像法律那样正式,违规惩罚也并不像触犯法律那样严重。假设我是个粗鲁的人,我绝不会因此而入狱,但会发现周围人很难与我相处。

如果免除了惩罚手段,道德选择就会成为一个很有趣的讨论话题——即使社会规则失效,你也还是会为了社会福祉而令个人意愿让步吗?

游戏中的冲动、影响和道德

游戏中的冲动元素:游戏都有一些限制条件,或者说是一套游戏规则。玩家在游戏中并不能随心所欲地行动,实际上,他们在游戏中所能做的事情远少于现实世界。但人们还是觉 得在游戏中比在现实生活中更自由。

这是因为许多游戏虽然都在模拟现实,但却只是现实生活的简化或者超现实主义翻版。它们比现实生活中的约束更少,原因在于它们仅局限于狭碍的交互行为,在这种有限的范围 内,游戏可以移除现实中的许多约束。

例如,在《侠盗猎车手3》中,我虽然不能做参加厨艺培训班,不能躺在沙滩上晒太阳,不能纹身等许多事情。但却可以射杀他人,盗窃任何一辆汽车,并且在马路上横冲直撞却无 需担心因车祸受伤的问题。

我不能在游戏中做一些事情是因为游戏本身并不涉及这些内容——只要我自己不并不想去做这些事情,它们就不能算是限制性条件。只有当游戏激发我们进行某些操作的欲望,但 却无法令我们实现时,我们在游戏中的冲动才会受挫。

例如,在一款破坏箱子的游戏中,我们发现两个箱子堵住了一个门口,而我们却不能去破坏这个出口时,我们就会感到失望。假如这里原来并没有这个门,我们就不会对门外边的 世界产生期待。

冲动对装饰层面的心理也有影响。例如,在《模拟人生》等支持玩家发挥创意装饰内容的游戏中,玩家可以选择今天用蓝色的墙纸,明天用红色条纹的墙纸。玩家的这种反复无常 的个性并不仅体现在装饰虚拟玩具屋,游戏中的虚拟角色形象也是这种心理的体现。

由于游戏模拟现实的精确度日益上升,冲动性选择也开始逐渐成为游戏中的一个强大元素。随着游戏深度和真实现的提高,玩家将可在游戏中满足更广泛的冲动而无需担心会有什 么风险。

游戏中的影响:我们可以将游戏视为一个系统,玩家则是系统中的一分子。玩家在游戏中通常以虚拟形象示人,但有时候则像是一个不可见其形的天神,以其无穷的力量影响游戏 世界的变化。无论是哪种情形,我们进行游戏设计时都必须承认玩家对游戏的影响力。玩家对游戏施加的影响各不相同,既包括可一直产生回应的操作,也包含那些导致玩家需持 续重建游戏世界的行为。

关于持续影响的一个早期典型就是《吃豆人》,玩家在游戏中逐渐消灭界面中的豆子,而在现代射击游戏中,玩家甚至可以完全摧毁周遭的环境。

例如《上古卷轴》系列等现代RPG游戏致力于打造一个“富有生命力”的世界,整个游戏过程始终贯穿玩家所做出的抉择。从这个极端例子来看,这里产生的持续性影响意味着玩家 无法不计后果地肆意妄为。

但具有持续影响的行为也有一些好处,它会增加玩家决策的重要性,让玩家的游戏体验更具沉浸感,使虚拟世界更具真实感。这种影响是以一种趣味为代价而催生另一种趣味性。

天神类型的游戏采用的是最为极端的做法,其影响力不仅是一种真实感来源,而且还是游戏的娱乐之源。在这类游戏中,玩家不再只是个简单地应付自己的决策所产生的后果。玩 家在这里是天神,可以随心所欲地主宰他人的命运。

而在《文明》、《黑与白》或《模拟城市》中,玩家拥有掌握整个社会命运的主导权,而且不需要担心其决策的直接后果。这些游戏当然也有一些明确目标,但其目标的重要性多 数时候要让位于自由选择和影响这两个要素。我记得小时候玩《模拟城市》时,我是同龄人当中少数乐于建设城市而非摧毁文明的玩家之一。

游戏中的道德感:到目前为止,游戏中的道德元素仍然有限。这从不少玩家在游戏中屠杀千万敌军、进攻NPC的房子并将其洗劫一空等行为就可以看出端倪。

但电子游戏的深度和游戏体验都在日益增强,它们对现实世界的模拟也开始更上一层楼,并且更易于将现实社会中的道德观植入游戏世界。

许多现代游戏采纳了这种做法,在游戏玩法中引进了简单的道德或者因果关系。在这些系统中,玩家的某些行为会产生因果报应,而其他行为则会减少报应,结果就是玩家会被贴 上“善良”或“邪恶”的标签。多数时候,这种因果关系还会与解琐新功能挂钩,而玩家所作的选择可能会更具策略性而非道德性。

若要让决策具有真正的道德感,游戏就应该让玩家难以比较两个选项结果的好坏。例如,“邪恶”会带来财富,而选择“善良”则拥有好名誉,而这两者之间却难以进行转化。

《质量效应2》就属于分离道德选择的典型,它创建了道德立场模糊的场景,让玩家自己进行裁断。它其中的道德困境融入了重要但与实际游戏玩法无涉的故事内容。

《现代战争2》则是一个不同的例子,其中有一个富有争议的机场大屠杀情景,玩家在其中的任务就是向无辜的人群扫射。无论玩家是选择完成这项任务,还是简单地向空中鸣几枪 ,相信这个场景都会深深烙在他们的脑海中。

道德感并不仅局限于现实主义的电子游戏。Brenda Brathwaite广为人知的试验性桌面游戏《Train》也通过简单的玩具火车和木制人质呈现游戏中的道德压力。该游戏的目标是让 玩家尽可能在火车箱中塞入更多人质,然后将车箱推向轨道,它让玩家将自己想象成一个把人质押送到集中营的德国军官。

因为道德感具有天然的主观性,我们最好从客观角度设置道德元素。不要给玩家强行贴上“善良”和“邪恶”的标签,而要创造与现实生活类似的道德困境(例如,牺牲小我成全 大我),然后让玩家遵从内心的想法作出抉择。假如道德选择过于倾向于其中一方,我们可能就需要向其添加策略性的动机以“平衡”选项,并鼓励玩家自己权衡利弊。

结论

人们每天都会遇到各种相互冲突的需求。例如索取资源的自私需求与为后人留下遗产,尊重他人的道德需求之间的矛盾。为平衡两种需求而采取的折衷做法总是无法让人们为其中 一个选择感到满意。游戏为玩家创造了一个有机会行使权力、施加影响力和履行责任的虚拟环境,他们在这种情境中可以自由探索现实生活所无法给予的各种选择。

如果要让这种移情体验更为形象,那就要让游戏环境准确模拟现实中的选择情境。

竞争

我们对胜利的激动和失败的痛苦这两种情感并不陌生,除非你一直受到父母无微不致的呵护,否则肯定都经历这两种极端情感。

竞争描述的是一种双方或多方参与的状态,其结果必定有输赢。正如前文所述,竞争具有情绪化特点,以致于有人困惑为何不将竞争划入情感元素之列。但我们也有足够理由可以 解释这一点,例如,许多成人只是单纯为了竞争而做出一些情绪化且不合时宜的举动。

我们之所以将竞争独立讨论,还有一个原因是,缺乏竞争元素,游戏中的情感就会有所差别——玩家可能会对游戏主角心生同情,而有了竞争机制,游戏主角就是玩家的化身,他 们对人物的同情心理则会更直接而具体。

可以说,竞争是传达情感的一个工具(尤其有助于创造戏剧性效果),人们置身于竞争状态时,往往无法分清现实与虚拟,他们仿佛身临其境,与游戏融为一体。

这也正是竞争的强大之处,竞争是一种原始情感,它会让期望、紧张、害怕和兴高采烈等情感不由自主地喷发出来,这是一种像坐过山车般无法预期的兴奋情感。

竞争的形式

凡是可以衡量比较的事情都具有竞争性,主要可划分为7个大类:

肢体技能:这是关于力气、速度和精确度的比较。其例子包括棒球、冲浪等体育运动,以及《Pong》和《使命召唤》等对玩家反应要求较高的电子游戏。

创意技能:其范围包括绘画、舞蹈、烹饪、指挥、写作等。这种竞争的目标是发挥创造力,博得评委们的认可。

策略技巧:它包括任何与策略相关的领域,例如理解和预测一个系列的行为表现(包括其他玩家的影响力),其例子包括《文明》、国际象棋等。

外交:它包括理解和预测潜在友盟的行为,并以富有影响力的想法采取相关行动。一般可称为政治或人气,其例子包括选举竞争、划分阶级以及多方战争游戏。

知识:它考验玩家对规则或事实的精通程度和积累,其例子包括桥牌以及知识竞答等。它也可以包括策略技巧元素——如果某个系统的规则并无定论,那么其中的最佳策略就是胜 者。

时间:这是考验耐力和耐心的竞争,其例子包括参与广播电话交谈节目,黑帮题材的在线社交游戏,或者凝视大赛(游戏邦注:这是让参与者睁大眼睛,看谁最先眨眼的比赛)。

运气:比赛结果具有随机性的竞争活动,例如掷骰子游戏、纸牌游戏、体育运动、赌博等。但由于现在许多人都知道结构分析法,人们已经可以预测这种竞争的统计概率,如果多 次试验几次,这种运气游戏也迟早将演变成一种统计知识竞赛。

从许多例子来看,一种竞争状态都会同时体现出以上的其中几种形式。例如《命运之轮》这个电视节目考验的就是参与者的知识积累和运气,而《疯狂橄榄球》则不但要求玩家具 有肢体技能,而且还要具有对方球队的背景知识,擅用相关策略应对该队球员,《星际争霸》则几乎包括以上所有竞争类型(除了创意技能之外)。

零和博弈

在真正的竞争状态中,玩家的胜利结果取决于其他参与者的表现。这意味着,假如有一名玩家获胜,其他玩家则必败无疑。

所有人都是赢家的竞赛绝非零和竞争状态。只要有一名玩家比其他玩家赢得更多,这种竞争就可称为零和游戏(在这种情况下,那些表现一般的玩家所获结果都是零)。

但零和游戏中的赢家和输家数量并不需要对等分配,例如《大富翁》中有一名玩家赢了,那么其他玩家就都输了,而在轮盘赌游戏中,只要有一名玩家输了,其他人就都是赢家。

在一些竞争性环境中,零和博弈可能无法明确体现所有玩家的成就和表现。例如,某个社区是根据玩家表现进行排名,但系统仅显示跻身前10强的玩家排行榜,而剩下的玩家成就 排名并不为人所知(排在第4557名并不是个好成绩对吧?)。

问题就在于,无论你采用的是明示还是暗示手段,玩家就是想知道零和博弈的确切结果。

非零和状态

采用非零和博弈的竞争并非与其他玩家相较量的竞争,而是玩家与系统的竞争。虽然我们可以比较玩家的游戏进程,但这是根据游戏系统的普遍门槛来衡量玩家进程,并不具有相 对性。非零和状态的优势在于,这种竞争中没有输家。而其潜在劣势就是这种人人共赢的结果会削弱玩家获胜的快感。

公平

并非所有的竞争都很“公平”——这意味着并非所有竞争者的起点都一样,都有均等的获胜概率。而游戏这种娱乐形式却始终在追求公平性,给予玩家几乎同等的获胜机会。其唯 一的不公之处就在于玩家本身的能力(游戏邦注:例如肢体技能、策略技巧等)不平衡。

破坏游戏公平的另一种做法就是“购买”优势。这种方式可以让游戏开发者大获其益,但却可能对游戏的整体布局造成影响,因为它会削弱其他竞争形式(例如策略、技能等)的 重要性。

多数社交游戏的收益来源于这种购买优势的机制。人们已普遍能够接受时间与金钱等价的说法,在当前这种按时间计费的社会中,我们已然习惯于将时间与金钱划等号。

隐藏失败

几乎人人都喜欢获胜,没人希望失败。竞争之所以如此具有吸引力,原因在于它既产生胜利兴奋感也伴生了最让人不悦的感觉,即失败的丢脸。

有些社交游戏成功地在让“人人皆赢”的情况下,制造了一种零和博弈的假象。坦率而言,这意味着这些游戏系统通过“补偿”输家而掩盖失败。例如,在《大富翁》当中,玩家 每次踏上对手的地盘时,银行都会帮他们偿还大部分债务。

这种手段造成的一个后果就是打破游戏经济系统的平衡,另外就是让游戏永无终结(多数社交游戏采用了这种做法)。

竞争的运用

在本系列文章中,竞争也许是与游戏最有关联的趣味性元素。竞争对非游戏活动的主要作用之一就是令其显得更像游戏。

而且我们也很容易运用这种元素——只要简单地衡量参与者的表现,并与其他参与者进行比较,这种情况就属于竞争。但正如我前文所述的观点,竞争是极具情绪化的元素,因此 很容易给参与者带来压力。

在游戏中植入竞争元素也许是可取做法,但在非竞争活动(例如跑腿打杂等)中融入该元素却未必能取得理想效果。

无论结果更好还是更坏,竞争元素都会改变一种行为或活动的整体情境,但我们不能轻视这种变化。

身份(Identity)

身份描述的是呈现个体特征的属性。从字面上看,它指的是我们如何定义自己,它可以反映已知与预期特性这两者的对比情况。例如我可以用以下一些特性来描述自己:

我讨厌哈蜜瓜,我在加州北部长大,我31岁,我喜欢桌游。

虽然上述内容不多,但你应该可以大概得出一个模糊印象,知道我的品味,我的成长环境和年龄,我的其他爱好等。

如果说你真能得到什么结论,那也应该是通过心理比较而获得的结果,比如将你自己和所描述的个体(我)进行比较,或者将个体与你所认识的其他个体相比较。

关于身份的学术研究

在学术界,现代身份心理学方面的研究多以Erik Erikson的理论为基础,他提出了“身份危机”的概念。这位美国心理学家因提出人生不同阶段的身份发展模型而得名,许多新 Eriksonian学术研究主要围绕多种“自我”而展开:你认为自己是个什么样的人,这通常与你在社会环境中所表现出的自我并不相同,其中包括身份探索(人们尝试成为某种身份 的人),社会身份(游戏邦注:也称社会认同),以及理想自我(个体所追求的身份)。

这些学术研究将身份描绘为一个动态而易受影响的形体,而非人们所相信的一种与生俱来的样板。

身份的两面性

从身份的动态甚至是试验性特征来看,我们不难发现角色扮演元素在游戏中的重要性,但我想这里就会涉及到第二个与游戏中的身份元素相关的话题——社交目的。

角色扮演:我曾将“选择”和“身份”的角色扮演话题一分为二。对“选择”来说,角色扮演与获得制定决策的权力有关,而对“身份”而言,角色扮演则与尝试改变自我有关。

社交目的:它描述了一种认同需求,它不仅仅包括建立联系或达到预期,实际上还暗指我们为他人创造一些价值的内在渴望。简而言之,社交目的意指个体希望自己被他人所需要 。例如,他不玩游戏了,会不会有人注意到这一点?

到这里,我开始怀疑“身份”这个词在本文的适用性。任何代表自身喜好和倾向的内容,是否都能划入身份元素的行列?例如,我所做的一切选择,以及成长轨迹是否都算是我的 部分身份?

最后我所得出的结论是:所有的喜好和倾向都可以视为一种隐性的身份影响力——它们本身具有不容忽视的优点,它们对身份所施加的影响只是其发挥的第二作用。而我们现在要 讨论的则是显性或不言自明的身份影响力(它们的存在目的就是塑造身份)。

而这其中的区别却会因动机而令人混淆。例如,我踢足球是为了享受竞争和决策的快感,那我的动机就是竞争和成长(克服挑战)。如果我踢足球是为了与“大众”融为一体,那 我就是为了获得认同/找到身份而参与其中。

先入为主的观念

我们潜意识中并没有发现这一点,身份在我们的日常生活中扮演重要角色。我们所体现的身份常会让相遇的人产生一种先入为主的观念。当你刚遇到某人时,经常就会通过一些细 节来判断或预测此人的一些相关信息。

例如,纹身、皮革、藐视权威的态度等信息可以用于暗示一个人的身份,金属框架的眼镜、实用的瑞士汽车也同样能传递某人的故事背景。

先入为主的观念有时候并不能反映个人的选择(例如种族和肤色),但那些可反映个人选择的信息却是促成社交关系的珍贵信号。

游戏中的身份元素

角色扮演:它是游戏中极易辨别的元素。拥有主角的游戏多少都带有些角色扮演色彩。而主角的故事背景和个性越是完善,游戏的角色扮演色彩就越是浓厚。例如,马里奥只是一 个没多少故事背景的普通角色,所以游戏中的角色扮演元素就较为有限。而蝙蝠侠是一个拥有丰富个性和故事背景的角色,以该人物为主角的游戏就更可能含有角色扮演元素。

虽然蝙蝠侠等家喻户晓的角色一般较有深度,但也潜藏着只能吸引小范围受众的风险(有人可能并不喜欢蝙蝠侠)。因此《神鬼喻言》和《质量效应》等游戏就采用了设定丰富故 事背景,但角色没有详细个人特征,它们通过牺牲角色深度和重玩性(游戏邦注:较无深度的角色可能会削弱游戏重玩性)以吸引更广泛的用户。

尽管“身份”和“选择”这两个概念之间有许多重叠性,但我认为二者之间的区别在于:我们扮演角色是为了获得不同身份的感受,也就是让自己所采纳的身份支配我们的选择。

如果我是蝙蝠侠,现在可以处置Joker,我就会将其放生,因为这就是我所接受的人格——蝙蝠侠的行事风格。

换句话说,如果我玩一款游戏的时候完全随心所欲,那我就是在行使自己的选择,而如果我是以游戏人物的身份参与其中,那我就是在扮演角色。

在互动在线多人游戏中,“真实”人格与“想象”人格之间的界线可能较为模糊。假如有人只了解你在游戏中的人格,并将它当真对待,那么这种人格实际上与“真实”人格无异 。我认为这种确认感是促使玩家融入虚拟情境中的强大力量。

社交目的:含有组队性质的游戏也都具有一定程度的社交目的。团队中的每个成员都在为共同目标而努力,大家都在为团队创造价值,而这也正是团队对成员的期望。

在足球队中,队员所贡献的价值可能就是射门、传球或防卫的技能。而在其他未有明确定义的情境中,例如校园派系里,帮派成员的价值或许就是所谓的“拉风”(酷)。如果个 体很酷,那么整个帮派也就很酷。

在某些游戏中,组队中的任何人基本上都扮演相同的角色。例如在《反恐精英》这类游戏中,大家阻队可能就只是为了消灭共同的敌人。在这种情况下,团队成员的价值可用所有 玩家都认同的标准(例如技能)来衡量,而“团队”也很可能因不同队员为炫出更强大的技能而分崩离析。

在另一些游戏中,玩家拥有不同能力,扮演互有差异的角色(例如不同职业),大家富有策略地进行协作。例如《魔兽世界》中的公会,就是由擅长承受攻击、攻击、群体控制和 治疗等技能的玩家组成。

玩家所扮演的角色不仅可体现自己在团队中的价值,而且还能体现自己的个性(例如反映玩家究竟是追求荣耀、关注、权威还是感激之情的人)。从许多方面来看,你所选择的价 值会显示你的社交身份——反映你和团队其他成员的关系如何(游戏邦注:例如玩家在团队中是医生,其职责就是照顾他人)。

实际运用

角色扮演:要让玩家扮演角色,就要为他们提供表现身份的方法。那么玩家要如何表现自己的身份?一般会先从个人资料入手——照片、兴趣等有利于表现自我的内容,但比表明 身份更重要的是“证实”身份。

玩家需要互动目的,他们需要特定情景。大家意见不一致时,若能善处理这种情况,也许是件好事。因为这可以让玩家保持个人立场,表现自己的身份。

纪念性选择:与现实世界一样,人们在虚拟环境中也会渴望表现自己。例如,电子游戏中的虚拟形象、装备和技能有助于其他人识别玩家个性。

非游戏环境的情况与此相同,也存在可被社区其他成员“识别”的纪念性选择。例如徽章和奖杯,但前提是其选择和行为具有价值。如果这种选择是大家并不看重的东西,那么它 也就不具有多大价值。

社交目的:如果说角色扮演为“表达身份”创造了机会,那么社交目的就是“证实价值”的桥梁。这意味着社区成员彼此需要,《FrontierVille》使用简单的“赠礼循环”人为地 强化这种效应,而且看起来至少对一些特定的用户很奏效。

而对于那些游戏目标用户之外的群体来说,这种机制的“强迫性”和“垃圾信息化”主要体现在缺乏针对性。

关键是要找到用户的价值所在。如果你是Facebook用户,那你看重的就是关注度;如果你是《使命召唤》玩家,那就是技能;如果你是问答论坛用户,当然就是准确而详细的答案 。

纪念性价值:在现实世界中,开昂贵的名车或穿着气派是一种成功的外在表现,对许多成功人士来说,他们希望找到谦逊与炫耀之间的平衡。在虚拟社区(如游戏)中,人们对谦 逊的重视程度多取决于系统本身特点。假如显示身份是约定俗成的惯例,那么人们就不会将其视为一种庸俗的“炫耀”。例如军官制服所别的一系列肩章,在军队环境中,这种显 示身份的做法并非不得体的表现。

只要有机会,开发者最好要在游戏或网站情境中引进可显示用户身份或价值的内容。

故事(Story)

在本文中,我把叙事和幻想作为“故事”话题来阐述,我对这两者的定义是故事中的“事件”和“背景”。虽然这些元素通常可以一概而论,但每一者在交流中都有自身的独特之 处,所以我要分别进行讨论。首先,我们将把故事视为“叙述”。

叙述(Narrative)

在游戏领域,人们通常会把故事视为一种存在于过场动画和对话中的非交互式体验。这种看法有一定道理,传统意义上的故事确实是一种被动体验,人们阅读书籍和观看电影的体 验并不会对(书籍和电影内容的)结果产生影响。

但从另一方面来说,这种看法未免有失偏颇。故事未必一定是被动体验。口头故事,尤其是即兴创作的口头故事,可能会因听众的建议而发生改变;而“即兴创作”的戏剧概念完 全是建立在交互式故事理念的基础之上。

有款纸牌游戏名为《Once Upon a Time》,它要求玩家抽取纸牌以综合话题,并最终完成一个共同即兴创作的故事。

如果你玩过这款游戏,就会发现这其中的故事基本上漫无目的,它们没有连贯的结构,开始到结尾之间也没有任何富有节奏或符合逻辑的进程。

被动叙述 vs 交互式叙述

令人愉悦的叙述一般都是精心制作的内容。它们会细心刻画角色故事背景,设计富有吸引力的秘密,拥有高潮迭宕的变化,以及令人情绪起伏的情节。Robert McKee备受赞誉的剧 本写作指南《Story》一书就详细列出了整个创作过程的要求。

但游戏开发者很难从中取经——他的方法不适用于交互式情境。玩家与系统之间的交互式故事必然会有散漫特点,要能够让玩家随心所欲,毕竟玩家有可能花半天去解谜或直接忽 略谜题,玩家可能不想开启某扇门,可能认为某场战役太容易或者太难。基本上,游戏玩法的线性特征越小,设计师对故事的掌控也就越小。

被动叙述的优势在于能够调动人们的期望和情感,而交互式叙述的优势则是增加选择和个性化特点。多数游戏会结合这两种方式,我们已经讨论过选择与身份的优点,因此现在主 要关注叙述的被动性。

被动叙述

既然被动叙述的价值在于期望和情感,那么我们就得详细分析这两项内容。

期望:我将引用McKee的观点和自己的一些见解来讨论这个概念。一般来说,故事会通过以下一些(或者全部)元素调动观众的期望:

神秘/悬念——未解开的答案

戏剧性转折——打破期望

道德/智力考验——促使观众思考:如果是我会怎么做?我要怎么解决这个问题?

这三者都会调动期望:前两者结合起来的问题就是,下一步会发生什么?最后一个的问题则是,我的解决方法或原则会管用吗?作者的想法会和我一致吗?

情感:被动叙述的另一优势就是能够激发情感。我在之前的文章中已经阐述过情感概念的内容,并将其视为玩家的体验,但在这里我们得承认情感也可以被玩家所察觉。

虽然人们喜欢在安全稳妥的环境中体会情感,但直接的情感也会让人产生压力。游戏中的直接情感退后一步来看就是具有移情作用的故事情感。读者在故事中可通过主角的审判和 胜利,或社会道德对反派人物的遣责而获得情感体验(游戏邦注:这两种情况通常会同时发生,例如警匪电影《爆裂警官》)。

游戏中的被动叙述

我认为被动叙述的优点来源于两种方式:

脚本事件

意外事件

脚本事件:这是指让故事遵循预先构建的路径,这也是绝大多数游戏所采用的方式。这不一定是指“线性”路径,但假如它采用非性线路径,那么就开发者需要因故事衍生出的多 个分支,投入更多资源开发有关游戏玩法的内容,这显然是一种不切实际的做法。

Quantic Dream作品《幻象杀手/华氏温度计》就是线性故事脚本的一个极端典型。该游戏甚至自称交互式电影,在主菜单显示“开始新电影”,并采用“返回”而非“重玩”按钮 。

许多游戏都在采用线性模式的同时,极力为玩家营造一种自由选择之感,鼓励他们探索故事内容,例如《塞尔达》系列不同地下城之间的一般关卡。采用开放式探索、可选择的独 立事件、支线任务等设置均可创造一种选择感,同时又不会破坏线性故事的主旋律。

意外事件:这是因社交互动而形成的故事概念。只要有足够的玩家和发生戏剧性事件的机会,玩家之间就会因共同合作、预测和回应他人的行为而自然形成社交框架,并产生悬念 、计谋、深度动机和共同感等内容。这里的故事多由玩家体验形成,而非脚本安排的结果。

意外事件的典型例子包括《部落战争》和《外交》,这两者的机制设计中均巧妙融入悬念、转折和道德等元素。MMO游戏设计师则常通过制造一些偶然性刺激因素,促使玩家在意料 之外的路径面临挑战。

实际运用中的被动叙述:将被动叙述植入非游戏体验的做法,与将其引入游戏内容的方式并无不同。因为游戏与网站或应用程序一样,原本就不是被动叙述的适用环境。以前的纸 牌游戏、桌游和体育运动都没有被动故事元素。直到角色扮演游戏,以及文本冒险游戏和《吃豆娘》(Ms. Pac-Man)中的过场动画问世,被动叙述元素才算被引进游戏玩法之中。

有两种方法可将被动叙述元素添加到与之无关的项目(游戏邦注:例如游戏、网站或活动)中,一种是以故事为主,然后添加情境;另一种是情境为主,故事为辅。

广告领域已能轻车熟路地驾驭这两种方法。第一种情况的案例如,电影中出现主人公手握一杯可口可乐的场景。而第二种情况的案例有DeBeers广告,它采用蒙太奇手法呈现一对情 人相爱和订婚的场景。虽然将这两者称为“游戏化”例子并不准确,但它仍然值得我们借鉴。

幻想(Fantasy)

故事的另一面就是幻想。虽然“Fantasy”一词常用于描述一种小说题材,但我认为将这个词称为形容为叙述内容所发生的“世界”(例如地点、文化、风俗、自然现象和科技等) 更合适,尤其是不同于观众日常体验的世界。换句话说:

幻想描述的是不同于我们所处环境的世界和居民。

而奇幻小说题材则将这个概念发挥到极致——它描述了完全不同于现实生活的整个世界。

出众的幻想

幻想的成功或强度(不一定是吸引力)通常取决于它能否遵从自身的“真实性”(即其所描述的世界规则)。它所介绍的元素对幻想世界的文化影响越深,其文化对角色的影响就 越大,而这个虚构世界也就越可能体现一致性和“合理性”。出色的幻想并不在于范围有多广,而在于一致性原则有多强。

这里我们可以使用80年代情景喜剧《Alf》为例,该剧的幻想内容描述了一个爱挖苦、爱猫、外向的外星人不幸在一个乡下家庭车库紧急着陆的故事。这就是该剧的幻想元素,而电 视剧的其他内容均取材于现实生活。《Alf》幻想元素的强大之处就在于,它能够使这个假设前提成立。假如Alf一开始就能跟外界沟通,找到工作和老婆,那么这种幻想可能就会 缺乏一致性和可信度。

这并不是说我们不能发展、升华原先的幻想内容,只是需要为改变的规则提供一个可信而能够保持内部一致性的解释。

幻想的吸引力

逃避现实主义的概念认为幻想的目的就是让观众从对现实生活中的不满中解脱,虚拟世界是一个更有吸引力的现实替代品。这意味着幻想世界的沉浸感越强,它的潜在愉悦感也会 越大。这种说法看似无懈可击,但我却并不认为如此,因为它解释不了为何同种幻想最终也会让人生腻。

有研究表明人类对未知结果的恐惧甚于对已知恶果的害怕,但人们却仍然渴望新体验。或许这正是幻想的吸引力所在——它为人们创造了无需面临任何风险就能尝鲜的机会。这种 吸引力相当于出国、遇见外国人、看到新鲜事物,它不会让人们面临丧失、受骗或被拒绝的危险。

幻想的实际运用

幻想是创造一种体验环境时可考虑的因素之一。某种体验越接近于另一种事物,就越可能创造幻想,用户就越可能想象自己身处某种从未体验过的状态。

举例来说,将一个网页体验打造成深山老林考古探险风格(例如,让用户拔开树叶进行导航,将文字内容写在废墟的石碑上,并适时制造丛林音效等),这可以在探秘和历险的幻 想情境中引出产品功能。

风险

比起游戏的其他元素,幻想可能更容易削弱某种体验的特点。暗示某项需要隐藏或更改的活动,很可能意味着该活动本身就缺乏价值。

游戏化活动要慎用幻想元素,必须确保这种元素能够与主要体验的基调和目标兼容。例如,以上所举的丛林主题网站就比较适用于“搜索”或“解密”的概念,但与涉及“建造” 或“纪录”的活动关系不大。

篇目2,Raph Koster回顾游戏趣味理论十年发展历程

作者:Leigh Alexander

10年前,Raph Koster在奥斯丁的GDC大会上做了题为《A Theory of Fun》的演讲,该书后来被多次出版印刷,现在每年仍能售出4000册,算得上史上最畅销的游戏书籍之一。

那时,MMO游戏开发元老Koster刚完成《Star Wars: Galaxies》,但玩家反馈该游戏并不十分有趣。Koster不知该游戏是否缺乏趣味元素,并决心着手研究心理学与认知科学(游戏邦注:Koster的同事Dave Rickey和Noah Falstein也是该领域的研究者),探索玩与乐趣的本质。

theory Of Fun(from gdconline)

科学指出人类在现实中常会无意识地进行模仿。诸如养育这些行为是我们生来就有的,而其它行为则需后天学习。随着时间的推移,对人类和动物而言,玩游戏变为一种重要的学习与练习工具,他们通过一起玩耍掌握基本的生存技能。

Koster表示:“如果你曾经看到小孩第一次学习走路,你会看到他们脸上洋溢的快乐:这种行为太有趣了。他们感觉自己像在玩游戏。”大脑会在从事有趣学习时分泌内啡肽,而《A Theory of Fun》核心内容中的基本概念探索人类的自然模式与系统,以便找到人们发现游戏具有吸引力的自然原因。

有些理论家将“游戏”与“玩”区分开,他们认为,游戏一般受到规则束缚,而玩则是无组织的自发行为,但是《A Theory of Fun》中的部分内容驳斥了这一观点。Koster指出:“你参加茶会,这也是一个学习系统。”

他继续指出:“如果你正在玩警察抓小偷、角色扮演或玩具,那么该系统包含的规则会多于《Candy Land》。其中的规则只会更多,不会更少……游戏通常涉及微不足道、具有约束性而且微小,用笔就可以记录下来的规则集。”

任何系统均接近游戏模式,由于游戏是根据更改我们大脑思维的学习系统而有意创造的内容,因此我们可以将游戏视为重塑人类大脑思维的一种艺术形式。Koster建议:“我们既然有能力这样做,那我们必须接手这个任务……实际上我们正着手研究直接的大脑控制领域。”

Koster最感兴趣的乐趣类型与流状态或快乐这种愉悦状态完全不同:“艺术具有挑战性,这是我们必须从事的工作。它很美好很快乐……它并非来自意外时刻。它让人快乐,但并非我们所说的‘乐趣’。”

Koster发现,乐趣非常依赖神经递质多巴胺的刺激作用。他解释道:“多巴胺是一种兴奋物质,它可以提高学习激情与记忆力。它与预测奖励结果有关,而这正是我们玩游戏时所追求的目标。它是大脑的指导信号。

当处于意外情境时,它也能发挥作用,激励你解决问题。同时,它能够缓解抑郁情绪。”

也就是说,多巴胺与知识的渴望程度有关。Koster提出:“也许乐趣不是‘学习’,而是‘对生活的好奇’。”

除乐趣以外,人们基于多种其它原因进行娱乐活动:专注于沉思、探索故事情节、获得舒适感,或者赢得比赛。以上均为玩游戏的正当理由,但与Koster的乐趣理论无关。

Koster提议:“许多人讨厌我们将游戏活动转变为机械模式。我不愿谈及这个观点,但在过去十年,如果出现越多这类科学理论,我们就越能证实这一情况。越来越多的论据显示,我们实际上可通过游戏学习重要而困难的内容,玩家更易通过游戏而学习,游戏确实具有治疗功效……这已经成为现实”。

现在就产生了关于“游戏”一词的有趣问题。抽象游戏仅充满挑战,而艺术游戏却不包含任何挑战成分,但是它们都统称为“游戏”。那么这有什么意义?Koster表示,游戏设计意味着创造系统,而不是创造视觉或创意元素。

他指出:“每款游戏都会首先以一个问题开场——比如,设置下棋桌,这就涉及到拓扑学的问题;要从盾牌后还是场景后射击太空入侵者是不同的问题……也是核心机制。游戏应告知玩家该如何行动。”

以《传送门》为例;你可以在宏观层面上获得整个游戏的胜利,也可以从较小水平上完胜某一回合,所有这些结果可归功于枪支的准确定位以及对游戏规则的理解。这种“微观”视角有助于解释说明游戏表层与实质的差距。

当然,不少设计师以更加精密的方式梳理游戏理论。在Koster的理论之外,Dan Cook在《Chemistry of Game Design》中提出“技能原子”理论;Ben Cousins测量了一系列在游戏间转移所需耗损的时间,并发现最佳时间。设计师们严密地研究游戏,定义自己的游戏科学,并列出图表加以解释。

可是,什么是游戏核心的黑盒子?Koster指出,游戏中只存在四个核心机制,理论上可归结为:试探性地解决问题,了解其它用户及社会关系,掌控自己的肢体状况,通过估算可能性来探索人类的天然困境。

游戏的核心完全取决于数学——但对于在诗歌领域取得硕士学位的Koster而言,他难以接受这个观点:“我觉得,数学确实难以表达所有事物。你要如何编写有关桃子口味的游戏呢?或如何表述一些妙不可言的事情?”

然而,许多艺术游戏(游戏邦注:比如Rod Humble的《The Marriage》和Jason Rohrer的《Passage》)都是《A Theory of Fun》的直接衍生物。Koster认为具有通俗性的娱乐形式位于某个极端,而具有学识要求的艺术则处于另一个极端。

娱乐具有保守性和熟悉感,而艺术却是我们无法理解的风险性与挑战性模式。这强化了一个观点,即情景喜剧有助我们规范社会行为,理解文化的表达方式。娱乐能提供模式识别的快感。但艺术具有挑战性,并且提供的是需要我们去学习和掌握的新系统。

我们制作的游戏更多趋于表面形式,鲜少包含“黑盒子”机制,游戏演变为按下按钮便可引发一连串事件的机制。Koster表示:“比起游戏机制,我们更容易通过故事和电影模式表达艺术。”那是否意味着像《Dear Esther》这种游戏可称得上真正的游戏呢?

“也许我们正在创作出一种不是‘游戏设计’的全新娱乐方式……我们可能需要一个新的定义,因为游戏设计是一种互动体验,但并非所有互动体验均是游戏设计。这可能类似于‘游戏故事与玩法的融合’,这或许就是为何单向平台游戏与人生意义,殖民主义和MMO可以自然融合的原因。”

Koster表示:“因为整个世界和游戏的发展模式均为如此,所以我将一切事物都视为系统?或者……因为游戏令我首先将所有事物当作系统模式,所以我才会有这种想法?因为我们是有意或者偶然疏忽而设计游戏,所以我们是在改变大脑思维。”

然而,为我们带来最大欢乐的当数游戏本质——社交联系、感恩、慷慨、乐观主义以及追求目标。

篇目3,列举游戏设计应注重视的8种趣味类型

作者:Cmurder

游戏其实是一整套规则,决定着进入游戏的玩家能做什么以及不能做什么。而我们又该如何制定一套有关“乐趣”的规则?这是所有设计师和制作人应该回答的问题。

以下我将列出游戏中8种类型的趣味:

1.感觉

游戏作为娱乐感。

.jpg)

Horror Games(from thegamecritique)

能够唤起玩家的情感反应。游戏通过视觉效果,声音以及节奏等元素而影响玩家的感觉。节奏对于游戏来说非常重要,特别是对于恐怖游戏。所以大多数恐怖游戏都能震撼玩家的感觉。

2.幻想

游戏是虚拟的。

所有游戏都带有一定的幻想。玩家经常能在游戏中获得一些在现实世界中所把握不住的强大“能量”。

3.故事

游戏是一个不断发展的故事。

设置游戏故事能够带给玩家一种使命感。并不是所有游戏都有或者都需要故事。故事同样也能被当成游戏的“目标”。就像在沙盒游戏中便拥有各种玩家所创造的故事。玩家通过游戏行动而去讲述故事。指向点击游戏便是基于故事的游戏典例。

4.挑战

游戏是一种障碍。

益智游戏便是如此。克服障碍本身就是一种奖励正强化(游戏邦注:一种以操作条件反射为理论依据,通过正强化塑造和巩固某一行为的方法)能让玩家知自己所做的事是对的。

5.伙伴关系

游戏是一个社交框架。

与好友一起游戏总比独自一人游戏强。团体游戏和多人游戏便属于这类型游戏。伙伴关系或多人游戏能够带给玩家额外的互动层面。而单人游戏则只能通过使用AI去模拟交互体验。

6.发现

游戏是一个未知领域。

发现不只是关于游戏本身,还包括玩家自己。冒险游戏便是一个很好的例子,但是任何能让玩家更好地认识自己的游戏都符合这一点。

7.表达

游戏是一个讲台。

trollface(from scirra.com)

表达源自游戏规则及其动态性。《我的世界》等沙盒游戏便是关于表达,但其实任何一款游戏都包含了这一元素。是否曾试图去打破游戏或破解它?自我表达便是人类本性的一大重要组成部分。

8.放松

游戏是不用动脑的消遣活动。

最显著的便是“刷任务”或“农场活动”。大多数游戏都具有这种形势。放松可以说是挑战的对立面。如果一款游戏只拥有挑战,那么玩家肯定很快就会关掉它。如果玩家抱怨游戏太难,那便标志着它未呈现出足够的放松元素。当然了,硬核游戏的放松元素就比较少。

以上便是设计师在创造游戏时需要遵循的一些规则。下次当你在玩一款“有趣的”游戏时,不妨问问自己它的乐趣是来自哪里。

篇目4,游戏中的“趣味”定义到底是什么?

作者:Oscar Clark

尽管我们一直在谈论趣味的重要性,但是我们却很少真正花时间去理解像“乐趣”和“游戏”等术语的真正含义。

这是我经常会略过的一些内容,有时候还会引用Rafe Koster的“快乐之道”。但是我也害怕我们有时候会因为过急而简化了真正的乐趣,并最终错失那些对设计有帮助的细微差别。

A Theory of Fun(from strangedesign)

我经常使用半科学语言将乐趣描述为人类成功创造一个模式或克服一个挑战所散发出的多巴胺或血清素。但是否只是这样而已呢?

早在1938年,Johan Huizinga便将游戏描述成是“日常生活之外的一种独立活动,能够吸引玩家完全投入其中。”

当我们不再抱着怀疑态度,并全身心投入游戏世界中时,自由感便会懵然而生;不管是面对短暂且有趣的休闲游戏还是需要投入更长时间的硬核主机游戏。

免费模式

还有人说游戏是一种“不带物质利益”的活动。

不管你是否同意这种说法,这都引出了一些有趣的问题,如博彩游戏是否适应这种游戏理念?MMO游戏中的“打金”现象是否会破坏乐趣?用户生成内容是否属于游戏的一部分?

如果我在游戏中花钱是否就打破了这种幻想?

在我们的全新免费领域中,最后一个问题特别中肯,因为它是关于花钱是否会破坏乐趣。这是许多免费模式批评者所发出的控告,我也经常对自己误解他们不能理解这一模式感到愧疚。但不管怎么说,我们都需要正视这一问题。

不断提醒玩家去购买东西只会阻碍我们“吸引更多玩家投入其中”。但是当我们着眼于原始数据时会发现,这种推广方式其实是有效的。

我们同时还需要让玩家知道自己在游戏中花钱是值得的,从而不会破坏他们对游戏体验的幻想。

社交化

Huizinga还说道:“游戏将推动社交群体的组成,他们将通过伪装或其它方式将真正的自己隐藏起来,并突出自己的与众不同。”

我之所以觉得这一观点如此有趣不只是因为它早于Facebook和电子游戏出现前便存在着,它甚至早于《龙与地下城》等游戏好几年便诞生了。我还觉得这一理念能够用于解释过去几年里游戏的发展。

让我们想想硬核玩家是如何将共享记忆与相互关系附加于特定的平台和角色之上。就像如果我说“The Cake is a Lie”(在《传送门》中,游戏主角将在人工智能Gladous指引下完成一串谜题,而Gladous称完成所有难关后会有cake奖励),那么玩过《传送门》的人应该都知道我想表达什么,他们肯定对此印象深刻。

我想仍旧有许多人不知道我在说些什么。这种内在了解是我们在玩游戏时所掌握的乐趣元素,并且这也是我们在社交游戏设计中很容易忽视的内容。

小众群体

当Zynga和Playfish出现并带领那些非硬核玩家的人一起进入游戏中时,游戏玩家也发生了改变。

Facebook游戏变成了主流游戏,玩家们都可以在此尝试各种社交体验。

但是那段时间也出现了许多问题,我并不打算在此重新描述—–不过有一个问题与这一主题相关,即Facebook并不能帮助玩家区分游戏中与现实中的自我。

“附属于小众群体”让我们损失了许多乐趣,即使我们能够获得更多可一起游戏的好友。

伪装

在1958年发表的《Definition of Play》中,Roger Caillois进一步延伸了Huizinga对于游戏的描述,并表明了怀疑也是游戏过程中一个重要元素。如果游戏中不存在不确定性,那么玩家就没有继续游戏的必要了。

这同时适用于游戏技能与运气中,因为如果玩家未能达到有效的平衡,游戏也就没有乐趣可言;这与游戏中不存在失败或成功的机会一样糟糕。

如果游戏中存在一定空间让玩家能够影响最终结果,那么他们便能够在游戏过程中找到乐趣。例如,玩家在玩《FarmVille》的乐趣并不在于创造自己的农场,而是源自独自创造的过程。

Caillois宣称,“伪装”也是游戏过程中一个非常重要的元素,不管是假装接受角色还是接受益智游戏的规则。

为了在任何游戏中做到这一点,我们就需要让玩家愿意暂停对于游戏规则的怀疑。因为只有这样做,玩家才能真正释放自己而尽情享受游戏乐趣。

情感回应

我的立场始终都是,乐趣是人类对于游戏最基本的情感回应,而我们的行为只会随着时间的发展而出现表面上的改变。

也许现在的我们已经拥有了掌上设备和云端计算,但最终我们所面对的游戏仍是一种自由的活动,并不会牵扯到任何物质上的利益。

乐趣并不受外界的迫使。它需要独立于常规世界而存在,并且通常情况下它都是与一些不确定的结果维系在一起,而我们也总是希望与其它玩家分享这种乐趣。

理解这一点,并考虑其中所蕴含的内容以及更复杂的商业模式和市场营销问题便能够让我们的设计工作变得更加有趣。

篇目5,Triple Town分享如何找到免费游戏设计的趣味性

作者:Patrick Miller

Spry Fox免费游戏(代表作包括《Triple Town》、《Realm of the Mad God》)获得成功的关键是什么?在日前的GDC免费游戏峰会上,该公司成员David Edery、Daniel Cook和Ryan Williams认为开发者应该关注早期原型以便完善游戏理念,制作出能够持续多年运营的在线游戏。

快速找到趣味性

Edery提到失败原型时指出,“对我们所制作的成功游戏来说,找到趣味性不应该花费太长时间——一般是几周,最多就是一两个月。我们曾花了6个月时间捣鼓原型,其实我们本该设置一个计时器,但我们却没有,因为我们对那个核心机制太着迷了。有时候过度沉迷于自己的理念才会造成最大损害。”

Cook解释道,“我们正在寻找一个能够让我们挖掘数年的核心、紧凑、健康机制。我们现在所做的就是将船开向空无一物的汪洋大海,四处寻找陆地。有时你会发现一些小岛,有时候会发现一片游戏玩法的大陆。我们将游戏视为服务,它们得长存数年之久。你需要的是能够让人们每周都投入数小时的东西,并持续数年保持它的新鲜感。我们所说的制作有趣的原型,就是指一个充满趣味的丰富世界。”

Edery称使用有助于快速创建原型的技术和工具是提高迭代速度的关键,“我们着实难以忍受那些减缓你短期目标的技术设置,我们需要每天迭代。我们不需要向那些之后才呈现出价值的技术投资,我们发现自己可以在之后需要的时候得到那些好处。所以我们一般使用Unity和Flash开发环境。”

Cook分享了他鉴定成功游戏理念的三个通用法则:势头(“游戏的趣味性是否会随着迭代而逐月增长?”,玩法空间大小(“我们如何添加内容?”),以及趣味的韧性(“你用一周时间故意让它变得很糟糕,但它却仍然不失趣味性”)。

triple-town(from mmohunter.com)

广泛的游戏设计潜力=广泛的盈利潜力

当你通过迭代获得一个极有前景的游戏理念后,你还得看看它是否具有盈利性。Edery以《Triple Town》为例指出,“你若使用了和我们一样的流程,你可能会想出一个非常有深度和可玩性的游戏理念,但在人们玩过数百小时后,游戏却仍无法创造任何收益。这种情况在我们身上已经发生了两三次。许多人误认为《Triple Town》是一款收益大获成功的游戏,但实际上并非如此。我们的收益大概是平均每用户投入4-6美元……这款游戏的趣味来自无需花钱但却能发挥更出色的表现。一般而言,你在多人游戏中花钱是因为可以向他人炫耀你的东西/本领。”

“从这方面来看,《Triple Town》是一个浅层的游戏体验。它有一些让人着迷的优点,但这却并非驱使你花钱的原因。如果在游戏中你可以想出三四种人们会想买的东西,那就差不多了。但在《Triple Town》中,我们一开始并没有自己考虑过这个问题。”

“当我们尝试在游戏后期添加这些内容时,游戏设计已经很紧凑和功能化,因此这一措施变得毫无意义。单人游戏现在变成了我们的形象工程,我们不能指望靠它们赚钱。”

尽早发布游戏

Edery将Spry Fox一些免费游戏的成功归因于他们更愿意尽早发布游戏,而不是像竞争对手那样直到满意为止才发布产品。“将游戏展示于大批用户面前,让他们自己玩游戏,你在这个过程中可以学到更多。比起竞争对手,我们发布游戏的时间会提前6个月到1年左右,我们会首先在加拿大发布游戏。”

美术风格最后定型

在快速创建原型阶段并不适合过早在游戏理念中投入情感——过早引进制作精良的美术资产就难以保持游戏变化的弹性。Cook称“你看到美术内容,就会以为这就是游戏未来的方向。但这并不是很可行,这可能会破坏整个创建原型的过程。美术人员要定期制作许多很棒的内容,我们则在制定许多流程。但我们每天在思考的时候都会面临一个选择‘因为这些美术资产看起来太漂亮了,所以我们得讨论怎么让它们派上用场’,结果就会出现一个艰难、累垮人的数学运算和抽象结构的游戏设计。并且每回这两者对接时,美术都会胜出一筹。美术创造的是情感投入,而在原型阶段你并不需要这些。我们现在就是以粗糙的方式创建原型,并且认为如果原型在很粗糙的时候都会有趣,它之后添加情感元素时就会更有趣。”

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4,篇目5(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

篇目1,Gamification: Framing The Discussion

by Tony Ventrice

[As a prelude to a full-on examination of gamification, Badgeville's Tony Ventrice digs deep into what makes games games, using work that's come before as a basis to explore this new tool -- the first of his ongoing series of articles on gamification.]

A lot has been said about gamification recently, and a lot of circular arguing has gone around what it means to compare an experience to a game.

I have two responses to this discussion:

1. “Gamification” as a term is indeed opportunistic and vague. While the word seems to imply a land-grab for everything that is great about games, in current practice it only represents points and badges: loyalty and reputation systems.

2. Games have a lot to offer, and the current form of gamification isn’t a bad place to start. There is a lot to be gained from tying loyalty and reputation systems to a website or product and, as the concept evolves, other aspects of gameplay are sure to follow.

What I would like to do is define the full scope of what makes games fun (not a trivial task by any means) and then explore the practical application to real-world businesses. This journey will be made in multiple parts.

Part 1 will be to dissect the concept at the intersection of the following words: Game, Fun, Play. The objective will be to end with a list of aspects — aspects of what make games fun.

Each of the following parts will explore how these aspects might be applied to business enterprise.

What Makes a Game Fun?

This question has been asked many times, by both academics and game designers. A common conclusion on the game design side is that games represent choice and learning. I’ll let a few of the most prominent experts in game design put it in their words.

Raph Koster says in A Theory of Fun:

Fun is the act of mastering a problem mentally.

Jesse Schell says in The Art of Game Design:

A game is a problem-solving activity, approached with a playful attitude.

I agree wholeheartedly. In fact, I came to basically the same conclusion when I defined gameplay for myself as: interesting decisions (apparently Sid Meier said the same thing — I may have got it from him.) I came to this conclusion because personally decisions and challenge are what I enjoy about games when I play them.

And this definition is perfectly functional if you’re designing games for people like me and Raph and Jesse; games like the video game industry has been designing for the past 30 years, and will go on designing for the next 30 years. A deeper understanding is only really useful if it’s your job to deconstruct a game and rebuild the “fun” in a completely new context, like, say, a corporate website.

An Unexpected Truth

Gradually, we’ve seen examples of games where the learning has been peeled away. FarmVille and Foursquare are evidence that people are willing to call something a “game” even if the decisions are vapid and the learning is simplistic. Defining a game by choices and solutions doesn’t seem to be enough anymore.

An argument can be made to defend the old definition. There is learning in FarmVille, if just a little bit. And Foursquare, well, I suppose you learn where you have a chance at maintaining mayor status and where you don’t…

But I’m not buying it. The fact is, the learning aspect to these “games” is so thin it hardly counts. Even if you posit that the average FarmVille player is less intelligent than the average “real game” player, it doesn’t explain why FarmVille players play for so long — we’re talking about months, more than enough time for even a simpleton to learn everything there is to know in the game.

The truth is, we have only two options: either refuse to call these things “games” or admit that there is more to games than just learning.

But before we move on, we’ll give the old definition one more chance. We’ll note that Schell and Koster didn’t say games were just learning, they said games were learning with a playful or fun attitude. Raph elaborates:

The lesson here is that fun is contextual. The reasons why we are engaging in an activity matter a lot.

So, the definition of a fun game is more than just learning, and neither Koster nor Schell has found it simple enough to condense into a one-sentence definition. Fun, it turns out is a very tricky word.

Once Again: What Makes a Game Fun?

The game designers had their say, and have given us the first aspect of fun for our list: learning. I think it’s a suitable first element, and examples of games where the fun is represented almost solely by learning might include pattern-solving puzzles like Rubik’s Cube or Mastermind.

I’m sure the designers have a lot more to say on the topic but, in the interests of time, I’d like to give the academics a turn now.

If you’ve read Salen and Zimmerman’s Rules of Play, you’ve heard of the sociologist Roger Caillois. Caillois posits there are four forms of play:

Competition, Chance, Role Playing and Altered Perception

The list seems rather arbitrary. As a sociologist, Caillois is not a game designer, but you have to appreciate the distance he’s given himself in his definition. And I think he’s made some rather unique observations.

Competition seems like an obvious addition to our list — almost any activity that can be measured has been turned into a game at one point or another, from spotting out-of-state license plates to shoveling coal faster than the other guy.

Role Playing also seems obvious — what other way can you explain children playing house, or firemen, or any other game young children play?

Altered Perception is probably Caillois’ most interesting proposal. From recreational drug use to rolling down a grassy hill and then attempting to run in a straight line, altered perception is an undeniable, albeit often over-looked aspect of play.

It even turns up in video games occasionally (some games “mess” with the player by distorting the reality of the game rules unexpectedly, while others bombard the player with lights and sounds, resulting in a “trippy” experience). I’m tempted to include altered perception to our list — yet, by and large, this is not an aspect of play with many practical applications, particularly in the context of business, so out of the interest of space, I’ll omit it.

Finally we have Chance. Chance is a mechanic desirable in competitive play to avoid deterministic outcomes. Given two players of unequal skill, in a game without chance, the outcome is known before the game even begins. Chance is a very important mechanic for game balancing and building suspense (something I’ ll get to later), but not inherently fun, or a reason, per se, to play a game.

Game designer Marc LeBlanc gives us a slightly longer and more practical list than Caillois. While LeBlanc might find better company in the previous section with the other designers, I’ve included him here because in his work he’s chosen to take a more academic approach (he’s even collaborated with academics at Northwestern University).

LeBlanc’s list of eight kinds of fun:

Sensation, Fellowship, Fantasy, Narrative, Challenge, Discovery, Expression, Submission

In the interest of time, I’ll cut through these quickly, picking out which to keep based on their value to our investigation.

Sensation might include fun things like the plunge of a rollercoaster, a runner’s high, or a pleasant massage — but in the context of gamified experiences, it is probably even less useful than Altered Perception.

Fellowship introduces the idea of a social aspect — a sense of friendship or belonging. Finding a single game represented purely by fellowship is difficult, but many people choose to play party games solely for this reason.

For example, I find Apples to Apples to be an asinine game — winners are chosen arbitrarily — yet I enjoy playing the game. Why? I find that to enjoy the game, I ignore the implied competition and learning, and focus instead on enjoying the social interplay and collective laughing. For me, the only reason to play Apples to Apples is the Fellowship.

Fantasy and Narrative are relevant but quite similar (I’d say they respectively describe the premise and events of a story). I don’t know if anyone would call a story a game, but in watching the interplay of a campfire story or a bedtime story you can’t help but see the similarities and at least admit the presence of fun.

Many games contain stories, and I have even heard of people playing games that were terrible simply because they wanted to know how the story turned out. I think this is enough evidence of fun to keep these two — at least as a single shared entry in our list.

Challenge and Discovery are What Koster and Schell were talking about (the player discovers new techniques and applies them to challenging problems) so we’ll categorize these with learnign.

Expression is very similar to role playing, and we’ll group the two for now and see if we can’t come up with a common feature.

Submission is, honestly, a bit unexpected. LeBlanc defines Submission as “game as mindless pastime”. Although this is a very tempting addition to our list, it unfortunately says nothing informative. By this inclusion, 3:00 AM television infomercials are fun, and I think anyone can agree that such a stretch results in a definition far too broad for our urposes.

We’ve made it through Marc’s list and retained 6 out of his 8 items, at least in some respect.

Next, I’d like to introduce an academic named Nicole Lazzaro. Nicole’s study covers the basics of choice and challenge that we’ve already talked about, but what she does differently is focus her studies around the emotional state of gamers.

In her own words:

Game Advertising Online

Our results revealed that people play games not so much for the game itself as for the experience the game creates: an adrenaline rush, a vicarious adventure, a mental challenge; or the structure games provide, such as a moment of solitude or the company of friends.

While she seems to view every aspect of a game from the perspective of emotion (and the utility of this perspective may be questionable) she does raise a worthy point: pure emotions most likely have a role in the concept of “fun”.

After all, why do people watch scary movies, flirt with their own spouses, play practical jokes on each other, or play Crocodile Dentist? They find surges of emotion like fear, arousal, humor, suspense and surprise to be fun.

I have one more academic who never seems to get integrated properly into these discussions, and his name is Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Csikszentmihalyi is the foremost expert in what we know as flow. In his own words, flow is:

Being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz.

Flow is often used to mean “balanced difficulty”, or is just as often dismissed as simply another emotional state. I believe the topic is actually much more interesting than either of these interpretations, and warrants its own entry in our list. For examples of flow that might be called “games”, I might cite bouncing a ball repeated off a wall or flinging cards at a hat. While these activities do involve learning a skill, I think the fact that it is a worthless skill might be indicative of something else going on.

What Makes a Game Fun? A Summary

We’ve heard from some of the most recognized experts on the subject (hopefully I haven’t abbreviated their voices unfairly), done some paring for utility, and here’s our working list of features that make games fun:

1. Learning / Challenge / Discovery

2. Role Playing / Expression

3. Competition

4. Fellowship

5. Fantasy / Narrative

6. Emotion

7. Flow

Before moving on, I’d like to do a little editing — nothing serious, just some renaming and a little shifting of shared similarities. I’ll include my reasons below for anyone who cares to argue.

Final List:

1. Growth

2. Choice

3. Competition

4. Identity

5. Story

6. Emotion

7. Flow

We now have a list of aspects that make games fun. I believe any proposed addition can be categorized under one or more of these seven. If it can’t, I’m more than willing to add another entry (or acknowledge and dismiss it, like sensation).

If we take the word “game” to be defined as: an activity engaged in for the pursuit of fun (and this is basically how the dictionary defines it), I think we’re ready to move on with our analysis of gamification.

In further articles, I will address each of the aspects on our list, what they might look like independent from the rest and how they might be used in a context outside of traditional gaming. Given the breadth of the content, I won’t be able to go into exacting detail, but I hope to cover each enough to set a trajectory towards further constructive thought.

How I Arrived At the List

For our first entry, we already have three proposed names: learning, challenge, and discovery. I would like to propose a fourth to represent them all: growth. Growth conveys an unequivocal sense of going somewhere, improving on a previous state.

What I prefer about “growth” is that it cuts more directly to the center of the desired experience than the others; I might be learning something, but not feeling as if it’s progressing towards any useful end. I might be challenged, but resent it as an unnecessary or pointless obstacle. I might discover something, but feel it to be irrelevant. Only growth clearly conveys both personal development and a positive experience.

Once you filter out the concept of story (covered under fantasy and narrative), role playing and expression are actually very similar. They describe an opportunity to assert the values that make you who you are and the freedom to try out new values without judgment. This seems to convey two things: identity and choice. Identity is important, but it’s already been covered elsewhere on the list (see below). That leaves us with choice, or autonomy, which is important enough to warrant an entry of its own.

Fellowship is a funny word that can’t help but conjure up images of Hobbits. What we’re really talking about here is a sense of belonging — a role, or place, in a social context. Nothing seems to describe it better than identity. I know who I am, and so does everyone else. While fellowship implies a purely friendly social relationship, friendship may be too specific — it’s probably safe to say almost everyone desires a sense of identity, but not everyone craves harmony and alliance.

For fantasy / narrative, as I mentioned earlier, these two respectively describe the premise and events of a Story. “Narrative” is a probably the more inclusive of the two, but yet seems too cold to properly convey the fun feeling of getting wrapped up in an engaging story. The users call it “story”, and I feel it makes the most sense to do the same.

[In the first installment of this series, Badgeville's Tony Ventrice looked to frame the discussion around what's possible with gamification by attempting to discover what makes games fun. In this article, Ventrice delves into the first two of his seven identified dynamics of game design.]

Growth

Growth describes a sense of direction and progress. It is a fundamental aspect of humanity, the first great challenge of adulthood, and a typical source of midlife crisis. When you ask a child what they want to be when they grow up, you’re asking about their plan, their direction for life. When, old and shrunken, you look back

over your life, satisfaction lies in what you’ve accomplished. Where did you start and where did you end up? When all is said and done, our entire existence is summed up as a story of growth.

Types of Growth

Growth comes in different guises, and depending on what you value and where you are in life, the ways in which you seek and measure growth will be different.

Children

For children, growth is literal: from the physical growth of their bodies to their gradual accumulation of adult privilege and responsibility, they are effectively growing to become “complete” and functioning adults.

Adults

But what happens when a child is all grown up? How does the definition of the word change? What is the meaning of growth for adults?

Even from a young age, children begin to supplement their literal growth with other forms — things like an expansion of knowledge, a record of accomplishments, an accumulation of order, and a network of friends. Once the body stops growing, and the basic rules of society are understood, the pursuit of these other dimensions continues, guiding us through the rest of our lives.

Not only do these other forms of growth provide individual motivation, they are, in many ways, the underpinning of our societies. Our desire for learning solves problems; our desire for competition challenges stagnation and finds optimizations; our desire for order preserves and protects; and our desire for connections promotes cooperation and bonds us together.

Now, most people probably never catalog their accomplishments by category, and there’s certainly no universally recognized list of measures, but I believe the four I’ve listed are fairly comprehensive — and if you bear with me a little longer, I’ll try to illustrate why.

The four basic types of adult growth:

•learning

•order

•challenges overcome

•connections

A Realization

While thinking about the measures of growth, I realized the list I was making resembled some other lists I’ve seen before — namely the Bartle test, the Myers-Briggs personality type indicator, the four humors of antiquity, or really any other form of personality classification system. Yet these systems tend to focus on determining personality types. Could it be that they also identify the general preferences along which people strive for growth?

Bartle

Meyers-Briggs simplification

Beatle

Growth preferences

Explorers

Thinking Introverts

George

seek questions and learning

Achievers

Feeling Introverts

Paul

seek order, balance and validation

Killers

Thinking Extroverts

John

seek competition and challenges

Socializers

Feeling Extroverts

Ringo

seek interactions and connections

While useful to understanding possible differences between individuals, I think these designations have always been potentially misleading when thought of as attributes or archetypes (such as the implication of the Beatles example). As attributes, there is a tendency to think only in terms of differences, but when considered as motivations, it’s easier to think of these four “types” as actually being present to varying degrees in all humans. In other words, an individual probably values one form of growth more than another but ultimately they’re all valuable, in some degree, to everyone.

Four Types of Growth, in Context

How do these four forms of growth manifest in game design?

Learning. Learning comes from deciphering the rules of a system. Typically, this follows a pattern of trial and error, forming hypotheses and testing them within the game environment.

To take a game like Street Fighter II as an example, the learning is in first mastering each move, then discovering effective combos, and finally identifying the best situational opportunities in which to use them.

Although learning is a means towards a competitive edge, it can also be a pleasurable end in itself; learning simply for the sake of the process. Why is the card game Bridge so widely appealing? Is it because there is always something more to learn?

Order. Order may seem like an odd way of defining growth, but I think it makes more sense if thought of from the perspective of rules.

There is a basic human desire to believe life has meaning and purpose and for this to be true, there must be implicit rules — concepts of correct and incorrect behavior. As a dimension of personal growth, order represents pursuit of following the correct path, however the individual may choose to define it.

In most video games, the motivation of order boils down to the act of following rules for rewards: collecting sets, completing tasks and leveling up. Those who seek order desire situations where the rules are clear and simple adherence is all that is needed to succeed. They prefer frequent and literal validation that the system functions and that it is guiding them towards a greater objective or higher status.

Challenges Overcome. If some thrive in order, others thrive in chaos. Life is constantly challenging and humans must adapt to survive against adversity. While the process may be exhilarating, it can also be painful and unpleasant; in real life, many challenges cannot be overcome at all, leading to discouragement.

Games offer a pleasant escape in that the challenges they present are almost always surmountable. In fact, if they aren’t, your design probably has a serious problem.

The difficulty with implementing challenge comes in the balance: too easy and it’s not challenging, too hard and it’s discouraging. Challenge-driven players need a regular cycle of challenge and success.

Connections. As Donne wrote, no man is an island. Making connections and sustaining relationships is deeply ingrained in all spheres of our lives and underlies our very concepts of civilization and society.

In games, social growth manifests as interdependencies — people who need you and people you need. From World of Warcraft raids to CityVille gift exchanges, the more connections and the deeper the dependencies, the more rewarding the experience will be to the socially-driven player.

Putting it in Practice

To investigate how growth might be integrated into a non-game environment, we’ll look at each motivator in a general context.

Implementing Learning. Learning requires only a system of rules. Any system could suffice, but obviously the more nuanced and subtly deep, the longer learning will be sustained.

Game Advertising Online

Unfortunately, there is an additional complication: the learning curve. Different users learn at different rates, and if you don’t want to lose audience, the learning needs to accommodate a flexible rate of uptake. An ideal learning curve provides a simple basic layer of interaction with the opportunity for deeper emergent layers (strategies, situational rule changes, etc).

In general, you do not need to design to add learning; you need to design to manage the learning you already have. Try to simplify the required learning and push complexity into “end game” objectives for your more advanced users.

Supplementally, challenges and game trivia can be entertaining and validating for the learning process, if handled unobtrusively.

Implementing Order. This is where badges, trophies, and the current idea of “gamification” has already bridged the span from game to non-game experiences. Badge-based systems are not new; from children receiving gold stars for turning in their homework to military officers receiving chevrons on their shoulders, they are a familiar construct.

Any meaningful experience can be commemorated with symbolic measures and, for additional validation, badges can be linked to rewards or privileges. For example, gold stars might result in candy bars, while chevrons bring rank an increased chain of command.

Implementing Challenges Overcome. Here we’re talking about the goal of overcoming opposition. The user wants feel magnitude and relevance — that his accomplishments are rare and special.

Yet in reality it’s logistically impossible for everyone to be exceptional. In a solo experience, where the player has no frame of reference as to how other players are doing, this isn’t a problem, as it’s not necessary to prove the magnitude of a victory. The game feels challenging, and there is no reason to think that it isn’t.

I’d say this sense of challenges overcome is the one thing, more than any other, traditional video games have relied on for fun so far.

In social environments, where players can compare progress, the weight of accomplishments may be devalued. If I complete a difficult challenge only to discover that most people achieved the same result in less time or fewer attempts, much of the fun of the accomplishment is lost.

To maintain the illusion, more complex strategies are needed. Strategies such as ‘framing’ victory (you’re the best over-forty, overtime, free-throw shooter) or simply sidestepping the problem entirely with misleading implications, such as letting both players in a competition think they’re winning (I’m looking at you, Empires and Allies).

If deception isn’t desirable, the best option is probably a mixed approach of solo and social challenges, with lots of little non-competitive victories to get users hooked, leading up to harder, more socially-contestable victories at the top: aspirational objectives to keep the most competitive achievers engaged.

Implementing Social Growth. There are a few provisions needed to foster social growth. First, there need to be venues of communication and collaboration. If players can’t talk to each other and interact in any meaningful manner, there’s no opportunity to make social connections.

Second, there needs to be a context, a social objective or at least a conversation starter.

Third, there needs to be persistence. Players need to be able to reconnect with the same people.

It should come as no surprise that these three are perhaps most clearly demonstrated by social networks, such as Facebook. Wall posts, messages, tags and comments constitute venues of communication, status updates and shares constitute context and the network itself represents persistent connections.

Intrinsic Motivators

When viewed collectively, the four motivations of growth often comprise a player’s most basic intrinsic motivations — motivations that the player carries with him into every context, be it a game, a job or an evening with friends. These are the motivations that, when actualized, are central to providing the long-term interest that keeps people engaged.

Emotion

Emotion is potentially a vague or equivocal topic and worthy of a little investigation before we dive right in to defining what makes it fun.

Enlightened thinkers have been making lists of “primary” emotions for a long time, with some well-known names including Descartes and Hobbes. And while lists are interesting, typically, they haven’t agreed on much beyond the fact that humans experience pleasure, pain, and some other stuff.

Fast-forwarding to the present, the situation doesn’t seem to have changed much. Robert Plutchik [PDF link], who is something of a thought leader in the field of emotion, has created an eight-point wheel with four spokes: Anger-Terror, Anticipation-Surprise, Joy-Sadness, and Admiration-Loathing. Plutchik made some questionable choices with his model, like using two dimensions to represent four, placing the axis extremities in the center, and suggesting the whole

thing be folded to form a cone.

Probably as no surprise, Plutchik’s model largely results in nonsense when you try to put it to practical use — where might I place jealousy? Pride? Lust?

Pity?

James Russell [PDF link] proposed an alternate model with a much more logical method. His “circumplex” plots eight basic emotions on a two dimensional graph with Arousal to Sleepiness along one axis and Pleasure to Misery along the other. Excitement, Contentment, Depression and Distress are situated in the quadrants between.

By limiting all emotion to an arousal scale and a pleasure scale, he at least proposes a measurable system.

While I don’t believe there is anything wrong with Russell’s model, it seems to be describing a different kind of emotion than the kind we’re looking for. Russell’s emotion is the primitive kind, the kind reptiles have, and not exactly the kind that is going to explain the appeal of a political satire or a taut thriller.The fact seems to be, if we want a practical definition beyond a simple measure of pleasure and pain, our science has yet to provide. Fortunately for this investigation, there may be a way of approaching the question from another direction.

Since the dawn of recorded history, the stories we find entertaining have followed a consistent template: genres. And the interesting thing about genres is most of them happen to coincide directly with specific emotions: Suspense, Romance, Comedy, Horror, Adventure, Drama and Tragedy. While this isn’t a comprehensive list of human emotion, it does appear to be a comprehensive list of emotions we explicitly seek for entertainment.

The Emotions of Entertainment

In game design, multiple emotions often turn up woven together in complex stories, but for our purposes we’ll attempt to address them in isolation, as part of the game experience itself, using the simplest, most pure examples possible.

Suspense (or Thriller) is perhaps the most common emotion in games, and turns up in any game with an uncertain outcome. An entire genre of kids’ games (that I like to call “Russian Roulette games”) is based entirely on suspense and includes the Water-balloon Toss, Crocodile Dentist, and Don’t Wake Daddy.

But more than these, any games that build on anxiety contain suspense, such as children playing hide and seek in a dark house, the card game Slap-Jack, and the aspect of survival horror games in which monsters spring on you from unexpected directions.

Romance has a few representatives that often share duty with suspense; Mystery Date is a weak example, as are likely those dating simulators sold in Japan.

Less vicarious examples include spin the bottle and strip poker; some would argue actual flirting and dating are part of a ritualistic mating game. I would also add that situations where sexual tension might develop in online social games should count (I certainly saw plenty of flirting when I was working on Zynga’s poker.)

Comedy is clearly a driving objective of many creativity-based party games like Taboo, Once Upon a Time, Balderdash, and Apples to Apples. The latter two even directly reward humor via voting mechanics.

Yet you probably won’t find more than a passing mention of comedy in these game’s rules; comedy instead seems to be an emotion just waiting to happen anywhere players are given the context to express themselves in a free format. As evidence, you probably don’t have to look any further than the activity of your friends on your Facebook wall to find a series of quips and one-liners.

Horror as entertainment requires a certain terrifying visceral experience that aims to instill disgust and build a sense of dread. While gladiatorial combat was probably quite the spectacle in its time, in the modern era horror as entertainment is largely limited to pure narrative fantasy. Horror games are usually clearly packaged, including the likes of FEAR, Resident Evil, BioShock and Dead Space.

Adventure covers just about every video game featuring a protagonist ever made. The player overcomes adversaries, cheats death, and races against time. In a lot of ways, adventure sits at the intersection of many of the other emotional genres; a little bit thriller, horror, comedy, suspense, and even romance. It covers none of these emotions too deeply, and perhaps this balance is what makes an adventure so universally appealing (and so unlikely to be obtained in

simple non-game experiences).

Drama is something of an umbrella term. Dramas tend to cover a range of emotions not already mentioned; things like jealousy, suspicion, honor, guilt, greed, ambition, ennui, and repression. Collectively, they seem to describe nterpersonal relations taken to dysfunctional extremes.

Game stories certainly take advantage of drama regularly (any JRPG), but in actual gameplay, games tend to rely on the more competitive aspects like suspicion and ambition. Multiplayer games that require balancing competition and cooperation, like Avalon Hill’s Diplomacy, represent the rare few that accurately model the emotional strain of shifting trust, honor and guilt of real drama.

Tragedy seems to be the least-represented emotional genre, with only the rare game dedicated to it (Shadow of the Colossus and Sword and Sworcery are two examples and both play tragedy with subtlety).

But this should be expected: to constitute a tragedy, the experience must ultimately be a failure, and failure is not a satisfactory outcome in most game designs. Although it is worth observing that, in most multiplayer games, everyone but the winner ultimately fails, and that in itself is something of a controlled tragedy.

Emotion is a difficult element to instill into games. It tends to be highly contextual and not usually pursued as an explicit objective beyond the scope of traditional story-telling. When considering emotion as a gameplay objective, I think it’s beneficial to view the available emotions in three groups of utility:

Those that integrate well with traditional game mechanics: Suspense

Those that can be worked into a design, if the proper considerations are taken: Romance, Comedy, Drama

Those that really only work in the context of a story: Horror, Adventure, Tragedy

[In the first installment of this series on gamification, Badgeville's Tony Ventrice looked to frame the discussion around what's possible with gamification by attempting to discover what makes games fun. Two dynamics he explored before were Growth and Emotion, and in this article, he tackles Choice and Competition.]

Choice The word “choice” could be defined to describe strategic choices or tactical risks. But those are topics we already covered when we discussed growth, learning, and overcoming challenges. The definition I would like to discuss now is: the freedom to choose and the freedom to act. To put it another way, I’d like to talk about autonomy.

Many of our modern cultures are founded on the concept of autonomy as an inborn right. We give it names like: freedom, liberty, and expression. It is a favorite topic of philosophers, and an investigation of the subject could easily lead to the likes of Locke and Kant, but for our purposes it shouldn’t be necessary to go that far.

Instead, I’d like to stick to simple definitions. To start, I think it’s safe to say every autonomous choice implies three potential considerations: impulse, influence, and morality. The desire to effect change, understanding the results of that change, and the moral implications of those results.

I’ll reiterate that these are possible considerations; a choice need not consider all three, but only a minimum of one (if it considered none, it would be essentially random, and not really much of a choice at all).

Impulse

To act on a sensation. Impulse is a very rudimentary aspect of the human psyche. I want something and I take it. I wonder what something feels like and I do it. Yet, as these two statements probably have already implied, we cannot follow through with many of our impulses.

In fact, I would estimate most of our impulses go unfulfilled. We know the repercussions of acting out, the risks of ignoring consequences, and we restrain ourselves.

But all this self-editing can be tiring. We yearn to express ourselves, to feel unhindered, free to do as we please. When people talk about “unwinding”, they’re talking about dropping all the restraint, the rules and restrictions — of going someplace safe where they can fulfill at least a small subset of impulse; be it a den, a hike, or a video game.

Influence

Influence simply states that for an action, there will be a reaction; for a choice, there will be a result. In the case of pure impulse, this relationship is rather banal: I choose strawberry jam because it will give me greater sensory pleasure than grape.

But in the case of choice based on predicted long-term influence, influence can be profound and life changing: I chose to pursue a Computer Science degree in Los Angeles and that choice directly influenced every event in my life thereafter, from the people I met to the places I went and the things I’ve done.

It’s also worth noting that choices not only have an effect on ourselves, they often affect others and our environment. And we typically like this. We the like feeling that our presence makes a difference. When it doesn’t, our role comes into question — sometimes even our very existence. If my actions have no impact, why am I even here?

To break this down even a little more, lets look into these different dimensions of influence:

Self. At the fundamental level, people in Western cultures feel a need to have an influence over their own fate. This is a primary expectation and carries some degree of responsibility (I am responsible for what happens to me). If I climb on the roof and fall off, I have to deal with the injuries I incur.

Environment. At the next level, people feel a need to have an influence over their environment — to change the conditions that surround them. This is a secondary expectation, and carries a moderate degree of responsibility (I am part of an environment and my actions will impact the future resources of this space). If while climbing on the roof, I damage it, I will have to deal with the leaks when it rains.

Others. At the third level, many people like having an effect on others, to share in their autonomy. This is a tertiary expectation, and can carry a high degree of responsibility (I have an influence over what happens to other people). If I cause someone else to get on the roof, I may be responsible if they fall off and hurt themselves.

Morality

The third aspect of autonomous choice is morality. Morality implies that, for many decisions, there are universally acknowledged right and wrong options. The moral guidelines are defined by society and may not always be in agreement with the desires of the individual.

Morality becomes a choice precisely when the desires of the self and the society are not in agreement; does the individual follow personal impulse or the precepts of decency? One the one hand, personal gain; on the other, social approval.

In strong societies, the choice of morality comes couched in the threat of punishment. For the punishment-fearing individual, real moral choice may be limited to the mostly trivial cases. For example, I may make the immoral choice to turn right at a red light without stopping (a minor moral infraction), but I would probably never consider murdering someone (a major infraction).

What we are talking about are laws and laws represent just the simplest example of society’s influence on individual choice. Society’s influence comes in other forms, less formal rules, things like decency, chivalry, respect and politeness. Each a form of moral choice, each adherent to standards determined by society. The rules are less formal than laws and so are the punishments. If I am rude, I’m not thrown in jail, but I may find that other people are less willing to cooperate with me.

Morality becomes interesting and potentially fun when you remove the threat of punishment. Many consider this to be the true test of moral fiber — will you defer your personal desires to those of the society, even when the society is unable to enforce its rules?

Impulse, Influence, and Morality in Games

Impulse in games. By virtue of the simple fact that games have limitations, they can be said to have rules. The player can not do anything he likes inside a game; in fact, there is very little a player can do inside a game compared to the real world. Yet, people often find games more liberating than real life.

This is because while many games model reality, these models are generally accepted to be simplifications or surrealistic interpretations. They are perceived as less limiting than reality because they focus on a narrow band of interactions and, within that range of focus, key restrictions have been removed.

For example, in Grand Theft Auto III, I can’t enroll in cooking classes, lie down on the beach, get a tattoo of a manatee or a thousand other things. But I can shoot someone with limited repercussions or steal any car I want and tool around town on the wrong side of the street until I crash and pop out, free from injury.

The thousands of things I can’t do are out of the scope of the game — as long as I don’t expect to be able to do them, they aren’t acknowledged as limitations.

Impulse only disappoints in a game when the game sets the expectation of being able to do something, only to prevent it from being done.

For example, in a game where boxes and crates can be destroyed, finding two crates blocking a doorway that cannot be destroyed disappoints the player’s impulse to find out what’s through the doorway. But if the door was never there in the first place, the player would never wonder what was on the other side of the wall.

Impulse also covers the dimension of decoration. A game that allows for decoration, such as The Sims, allows players to redecorate as the whim strikes them. Blue wallpaper today, red stripes tomorrow. This sense of capricious personalization is not limited to virtual dollhouses; it frequently turns up in the form of avatar builders that let the player change or evolve their in-game appearance.

Impulsive choice is a powerful aspect of games that is becoming increasingly relevant as games are able to model the real world more and more accurately. As games become deeper and more realistic, players will be enabled to indulge a wider range of impulses without risk of consequences.

Influence in Games. Games can be thought of as systems and the player should be considered part of that system. Often, the player is represented literally, through an avatar, but other times the player acts more like a god, influencing the game world from above with no physical representation within it. In either case, it’s a fundamental rule of game design that the game acknowledge the influence of the player. Influence can vary from actions causing reactions all the way to actions causing permanent reconstruction of the game world.

Persistent influence has evolved from early examples like Pac-Man, where the player gradually cleared the board of dots, to today where, in many modern shooters, the players can literally tear down the environments around them.

Modern RPGs, such as the Elder Scrolls series, strive to go even further and create “living” worlds where decisions follow the player through the game. Taken to this extreme, influence seems to be in opposition to the goal of impulse; persistence means players can’t act impulsively and without consequence.

But there is a benefit to actions having lasting effects; as decisions carry greater weight, the fantasy becomes more immersive. The fictional world feels more real.

Influence enables one type of fun at the expense of another.

God games take the most extreme approach, and embrace influence as more than just a source of realism: as a source of entertainment in itself. The player is no longer a simple actor who must deal with the consequences of his decisions. The player is a god, free to decide the lasting fate of others.

In games like Civilization, Black & White, or SimCity, the player has complete freedom to steer the fate of a society without fear of direct consequence.

Sure, there are explicit objectives to these games, but for many, they take a secondary role to the freedom of choice and influence. As a child, I can still remember discovering I was in the minority of my peers in that I played SimCity primarily to build cities and not destroy them.

Morality in games. Up until recently, games paid very little attention to morality. Conventions like killing enemies by the thousands, invading NPCs’ homes without thought and destroying furniture in the search for cash and power-ups are evidence of this legacy.

But as video games have become richer experiences and greater depth has been instilled into their worlds, they have come much closer to modeling our real

world. As the resemblance gets closer, it becomes easier to project the morals of our real world onto the game world.

Many modern games have embraced this convergence, introducing simple morality or karma systems into gameplay. In these systems, certain actions increase

karma, others decrease it, and the result is the player is labeled as either “good” or “evil”. More often than not, the karma system is also tied to the

unlocking of features, and the choice runs the risk of becoming more tactical than moral.

For a decision to be truly moral, the tactical results of the two options should be difficult to compare. For example, “evil” provides wealth, while “good ” provides reputation, and translating between the two is an inexact science.

Mass Effect 2 does a good job of isolating morality in choice by building morally ambiguous scenarios and then asking the player to arbitrate. The dilemmas involve significant story investment yet carry little actual gameplay relevance (at least that the player is able to predict while making the choices).

In a different example, Modern Warfare 2 has a controversial airport massacre scene, “No Russian”, where the user is asked to fire into a crowd of innocents. Whether the player chose to contribute or simply fire into the air makes no real difference to the progress of the game, but probably leaves a lasting impression in the mind of the player nonetheless.

Morality is not limited to realistic video games. A game need only evoke parallels to real-world moral choices to be effective. Brenda Brathwaite’s widely cited experimental board game Train was able to pose moral tension through simple toy trains and wooden pawns.

The objective of the game was to cram as many pawns into your boxcar as possible and move it to the end of the track. The moral difficulties arose from the aesthetic elements, which not-so-subtly invited players to imagine themselves as German officers tasked with transporting people to concentration camps.