万字长文,关于游戏在用户选择层面设定的考量分析,上篇

篇目1,如何在游戏中创造有意义的选择

作者:Brice Morrison

我永远都不会忘记Boyd。愿他安息。

Boyd是我的助手,朋友,亦是知己。我们彼此信任。但是当我们在《火焰之文章觉醒》的战场中陷入困境时,我意识到Boyd将不会取得成功。他被骑士比如绝境,无处可退了。在玩了几个回合后,伤害已经造成了。我在一开始所控制的角色就这么被杀掉了。

我感觉糟透了。他本来不需要死,游戏并未要求它需要完成战斗。这是我的错,是我引起不必要的杀戮。他是一个带有强大武器和铠甲的强大角色,但现在一切都消失了。

在剩下的游戏中,别人一直在提醒我所犯的错。他的兄弟会说:“我们可以这么做!我想这是Boyd想要的。”他的朋友会插话:“如果只有Boyd在这里,你也知道该做什么。”当我进入战斗中时我便会想到他有多有有用,但现在他却不见了。该死,这款游戏已经有10年的历史了,我仍然记得它,尽管已经不记得游戏中另一个角色的名字了。

我与Boyd的游戏体验,即虚拟选择折磨着虚拟角色,教会我作为一名游戏设计师应该在游戏中创造一种“有意义的选择”。选择将扣动玩家的心弦,让他们透过自己在现实生活中的角色更深入地感受游戏,并伴随着强烈的情感体验。只有这样的设计将能将游戏变成艺术。

但你是怎么做到?你是如何赋予游戏中的选择意义?

比起相信我的话,让我们学学专家的经验——2012年广受好评的《行尸走肉》,我认为这款游戏能够代表当下的艺术状态。

什么是有意义的选择?

.jpg)

choice(from gamasutra)

这类似于“游戏是不是艺术”的问题。这里存在选择空间。

对于我的设计以及本篇文章,我将更明确地定义有意义的选择。

有意义的选择要求如下四个组件:

1.意识——玩家必须知道他们在做选择(感知选择)

2.游戏玩法结果——选择必须带有包含游戏玩法导向和美学导向的结果

3.提醒事项——在做出选择后必须给予玩家提醒

4.永久性——玩家在探索完结果后玩家不能回头会撤销选择

如果都能满足这四个要求,我们便能够创造出有意义的选择。因为在现实生活中,这也是有意义选择的组件。

想想你在生活中所做的中做的决定——从哪里去学校,是否告诉你的朋友,与谁结婚,是否分手等等都带有这四个组件。而这些都是构成我们生活的种种选择。

在游戏中,基于这些组件的选择将唤醒玩家强大的情感反应,让玩家讨论,思考并记起某些内容。通过创造有意义的选择,我们也能让游戏变得更有意义。

让我们详细分析这四个组件。

组件1:意识

.jpg)

awareness(from gamasutra)

如果玩家并不知道他们在两个以上的选择中做选择,这便不会有意义。

想象玩家在一款游戏中,其中的角色Cindy正在呼叫救命。玩家跑过去帮助Cindy。那时候,游戏会说:“你选择去救Cindy而不是Bernard。”

但玩家却从未看到Bernard。他们甚至不知道Bernard陷入了麻烦,或者也不知道他的存在。这时候,玩家可能就会感到受挫。这就破坏了选择,导致它失去了意义。比起对Bernard vs. Cindy间的选择结果充满责任感,玩家将会开始责怪游戏。“什么?我并不知道需要救Bernard!我并不想要救Cindy的!”这看起来便不再是一种选择,最终出现的任何结果将被当成是不可避免的。

其次,玩家完全错失了思考,挣扎并决定自己想要做什么的体验。

《行尸走肉》是通过选择界面(游戏邦注:这是David Cage在自己的游戏《骤雨》和《Fahrenheit》所提倡的)去传达选择意识。大多数情况下当玩家面对一个选择时,他们便能明确地看到其它选择。

关于呈现给玩家多少意识全是取决于你。

在《行尸走肉》中,一些选择及其结果都很明显。这种情境与上述例子非常相似,玩家在便利商店中躲避僵尸。一群僵尸窜入商店中,两个角色被抓住,玩家必须选择救哪个。

这时候玩家会获得足够的时间去做出选择,并且被抓住的角色也都处于玩家的视线范围内。这让选择变得更加明显,所以当玩家做出任何选择时,他们都会具有责任感。

有意义的选择的意识水平非常广,甚至让玩家知道自己在做一个明确的选择。

举个例子来说吧,在游戏一开始与Hershel的交谈中,玩家被问到一些问题,“你们来自哪里?”“你是她的父亲吗?”“你们是和谁一起来这里的?”他们并不清楚哪个问题真正重要哪个问题只是闲话家常。但是,玩家仍然知道他们正在做出选择,即使他们不敢保证最终结果会是怎样的。谈话的界面让这一切变得明朗。

所以当Hershel在对话或谎言中抓住你时,玩家便会觉得这是自己的错。他们本可以说“我是独自一人”而不是“我与一位警官一起来的”,所以当Hershel谴责他们时,他们便知道这是自己的决定。

组件2:游戏玩法结果

想象你在玩一款游戏,你获得一个藏宝箱。藏宝箱里有两件东西:

1.一把更强大的新剑,能够一次击毙其它武器需要两次攻击才能打败的敌人

2.一把与你现在的剑作用相同,但是颜色却不同的剑。

你会想要哪个?显然你会选择第一把剑,因为它带有游戏玩法结果。

游戏玩法结果并不只是改变游戏的标志或声音,它也会改变玩家的行为和行动。它们不是只改变游戏的外表,它们也会改变游戏的行动。

最有意义的选择是既带有美学也带有游戏玩法结果。改变游戏体验和玩家的行为比反复玩带有不同布景的同一款游戏有意义多了。

在《行尸走肉》中便存在许多来自玩家选择的游戏玩法结果。在Kenny与Larry的战斗中决定支持Kenny影响着他对你的看法。在战斗中支持Kenny意味着之后当你陷入与Larry的混战时,Kenny将会对你提供帮助。这也影响着他是否愿意执行你的计划。

忠实于游戏前提,你所做出的选择将产生连锁反应,直至大结局。

最近发行的一款带有有意义选择的叙述类游戏,David Cage的《Beyond Two Souls》便是游戏玩法结果的反面例子。与大受欢迎的《骤雨》不同的是,《Beyond Two Souls》遭受到了来自玩家和评论者的鄙视与嘲笑。尽管图像效果非常显著,其游戏玩法似乎还存在很大的漏洞。

来自Ars Technica(游戏邦注:热门科技博客网站)的Kyle Orland写道:

在《Beyond:Two Souls》中我几乎不曾停下来考虑过一个选择。相反地,我一直朝着预定的故事节奏前行着,并在为察觉不到任何有意义的代理的情况下完成了一个老套的情节。

做出是否告诉Ellen Page他的着装与宾客不相称的决定并不会出现任何结果,除了只是改变对话内容而已。剩下的游戏只会是一样的。

通过为有意义的选择使用框架,我们可以假设《Beyond Two Souls》中的众多选择有些问题:它们没有足够强大的游戏玩法结果。结果这都是假设,可能Quantic Dream众多 团队已经证实了这点,也许玩家所做出的决定会让人感觉它们有更强的情感分量。

组件3:提醒

.jpg)

reminders(from gamasutra)

后悔是一种非常复杂的人类情感。不管是丢失了友谊的后悔,将过多精力付诸于工作室而没有足够时间陪伴家人的后悔,还是在有机会的时候从未去追求自己梦想的后悔。后悔是失望与责任感的结合,而现在悲伤难过也不会再带来你想要的结果,因为机会已经过去了。

骄傲是后悔的对立面。当你因为自己所做出的选择得到了自己所想要的结果时,你会兴奋,这便是骄傲。你会因为嫁给自己喜欢的人感到骄傲,你会因为选择了正确的工作感到骄傲,你也会因为做出正确的决定感到骄傲。

正是这些后悔与骄傲的故事构成了我们的生活。

然而,如果你不记得自己之前的选择,你便永远都不会感受到骄傲或后悔。如果你之前的选择并未影响你现在的生活,你同样也不会感受到这些情感。

在《行尸走肉》中,玩家会不断受到有关自己之前做过的选择的提醒。Kenny会喊道:“你从未支持我!”之后在游戏中出现的另一个角色会说“你在Motor Inn中未能保护她。”你所做出的选择不仅会对当下产生影响,同时还会影响你与其它角色的长久关系。如果Telltale未添加这些提醒,那么许多选择对于玩家来说也就失去了意义。

通过适当体现玩家他们之前做过何种选择,选择的分量也会变得更重。当玩家随着时间的发展而前进时,同样的选择会更多地影响他们的体验,并伴随着意义。如果你做出选择,然后忘记它而继续前进,你便不会在之后产生后悔或骄傲。

组件4:永久性

在《纸片马里奥:千年之门》的最后,最终boss问马里奥他是否想要加入自己的一方。而玩家可以在此选择是或否。

如果你选否,最后的战斗便会开始。而如果你选择了是,玩家便会看到“游戏结束”画面,并往前倒退10秒。

没有人将其作为揭示自己品格的最终结局。实际上,如果你能够回到过去改变自己的选择,那么再有趣的游戏玩法也会变得无聊。

现实生活中的选择之所以充满情感,悲伤和目的,是因为它们都具有永久性。我们不可能重新选择再来一遍。你只有一次机会,这也是为何你需要谨慎地选择自己的言行的主要原因。

而在你可以重置的游戏中,你却可以毫不犹豫地摧毁建筑或攻击无辜的人。

《行尸走肉》通过使用自动保存功能去处理这种情况。一旦玩家做出了重要的选择,游戏便会锁定它,从而确保它们不会倒回去。因此,面对自己需要做出的每个选择,你都必须确保那是自己真正的想法。

当然,玩家也可以重新开始或重置某一章节,但不便性也足以阻止他们这么做了。

结论

我希望这一框架对你们会有帮助。如果你能够确保游戏中的选择带有这四个组件,那么我相信你肯定能够呈献给玩家巨大的价值。

就像我之前所提到的,关于如何创造有意义的选择可能存在数千种方法,我所列出的是许多成功游戏反复实践过,也是对我自己非常有帮助的一种。

我相信游戏是一种艺术,而真正有内涵的游戏能够进一步深入电影和文学所呈现出的情感,甚至会做得更好。通过创造让玩家经由做选择而以人类的角度去评估自己的角色,从中吸取经验教训并应用于现实生活中的游戏,作为游戏开发者的我们便能创造出一些真正特别的内容。

篇目2,设计师该如何为玩家设置游戏中的选择

作者:Randy OConnor

据称真正的游戏是为玩家而非设计师提供情感控制权。但是我却不认可这一观点。事实上,给予玩家多少选择,选择将会带来何种影响以及玩家会如何做出选择等才是我们(作为设计师)对于玩家的真正控制。我们以何种方式呈现出何种选择都将决定着玩家的情感回应。

互动

racing(from gamasutra)

首先来说说玩家系统的互动。就像赛车游戏主要是关于玩家与界面间的互动。在这里选择是关于精通系统去获得预想的结果。选择并非取决于玩家决定该做什么,而是该怎么做,这种设计的情感力量主要源于玩家对系统的精通,了解什么才是最佳选择,并能够做出最有效的选择。

设计师必须选择如何去挑战这种系统精通,《使命召唤》便利用了这种情感设计原则。精通系统并了解如何通过有效互动而创造出特定玩家回应将能让玩家在面对这些选择时感到自豪和愉悦,并在未能掌握技巧时感到愤怒。除此之外设计师是否还能创造出更多情感回应呢?

像《星际争霸》等游戏便突出了这种系统精通,在游戏中所有优秀的玩家都将掌握热键的使用,清楚自己首先需要建造何种内容,以及获得更多选择需要何种技巧等等,《星际争霸》还通过获胜条件去限制了玩家能够获得的选择。

选择的广度

这是关于我们所做出的选择在整个游戏系统中具有何种意义。游戏中包含了叙述系统和目标互动系统,这是两种功能性游戏元素,而如果设计师能够做出合理的选择,这两大系统便会具有非常重要的功效。叙述系统是关于环境和外观,而目标互动系统则是关于游戏内部的功能。这主要是关于我们为玩家提供了多少选择以及这些选择各属于何种类型。

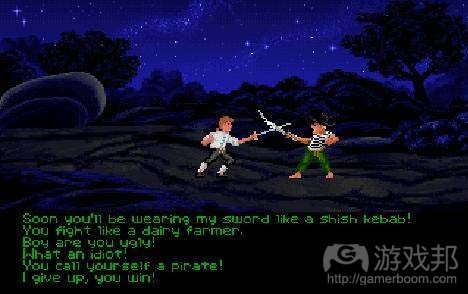

adventure game(from gamasutra)

目标关卡互动选择主要是关于玩家如何改变他们的游戏世界。Lucasarts的冒险游戏便是关于挖掘游戏中双关语的深层次含义,寻找各种不同的目标以及它们的用途等。审查,打开和谈论就相当于一款射击游戏中的射击,恢复生命值和扫射。不管是Schafer(游戏邦注:现任Double Fine Productions创始人,制作了许多大受欢迎的游戏,如《猴岛冒险》等)还是Gilbert(著名冒险游戏创作人)都致力于创造目标互动关卡(目标便是创造情感和笑声)。就像在《猴岛冒险》中阅读一行对话不仅能让玩家感受到幽默,同时还能从中获得进一步前进的选择,并让他们能够深入挖掘对话在系统中的内在含义,而是否让玩家阅读对话则体现了冒险游戏故事写手所掌握的特权。

其中也包含着设计师所具有的权利。在冒险游戏中,玩家将多长时间才能获得一个选择去推动角色前进?在系统中某一功能是否具有意义?不让玩家做任何事情,只让他们行走并谈话,并使用一些琐碎内容推动故事前展的选择,已因其运用广泛而成为冒险游戏中的一种特定选择。

围绕着这些稳定且清晰的系统,类型将不断发展着。面对某些玩家我比较了《火星漫步》与《银河战士》的游戏世界结构,对于他们来说这便是他们理解中的游戏世界,但是从某些方面看来这却是一种不合理的比较。

如今的射击游戏都拥有掩体系统,因为这是所有人都认可的系统。我曾多次提及希望看到更多不同肢体互动系统的出现。是否曾有人开发出一些会让你费力装载弹药,操作武器的过程如同射击一样复杂和费劲的游戏?《孤岛惊魂2》有一个让玩家自制枪支的机制,虽然这种设置有点意思,但它真的让游戏更有深度了吗?如果游戏让玩家必须不断地重置子弹,便会带给他们完全不同的情感反应。

《模拟城市》又是怎样的情况——包括城市的创造与毁灭,玩家选择的广度等等。游戏中所具有的创造,毁灭与维护,以及玩家所做出的选择都与推动线性故事发展的目标毫无关系,而是Wright根据玩家想要看到的以及玩家可能采取的行动所做出的选择。

环境选择是游戏情感设计的前沿

环境选择是我们在游戏中所做出的有意义或无意义的选择。游戏中既存在着积极/具有创造性的选择,也不乏消极/具有破坏性的选择。当我们想要选择时游戏中可能就缺少选择,而当我们被限制在一个狭窄的环境中时游戏又会为我们呈现过多的选择。《模拟城市》的某些场景为玩家呈现出了环境选择,但是更多情况下玩家都是在此建造属于自己的城市。

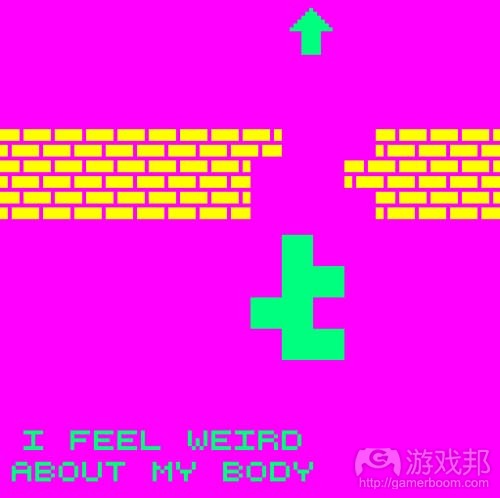

Dys4ia(from gamasutra)

Anna Anthropy所制作的《Dys4ia》便是一款很棒的游戏,我之所以喜欢这款游戏是因为设计师在故事环境下限制了玩家所面对的选择。玩家可以基于任何顺序去体验不同的环境,但是就像生活一样,当玩家真正适应了这种环境时,他们便会产生各种好奇。我们甚至会在自己拥有任何权利和控制力量时感到惊讶。就像吃药的“选择”便具有冲突,我也想知道我们真正能够拥有多少选择?

我不喜欢《侠盗猎车手IV》便是因为游戏环境明确表示我并未拥有任何选择,但是游戏却呈现出一个开放的系统。当我将驾车驰骋并无视Lil Jacob的呼叫时我便只会遭遇惩罚。让我感觉自己好像因为接触了游戏所怂恿的各种系统而遭遇了惩罚。游戏中穿插了各种各样的故事,设计师并不希望玩家自由穿梭于城市中。但是这些故事却不够多元化,难以为玩家有效地呈现出一座美丽,广阔且健全的“自由之城”。我便是因为这款游戏的环境选择而倍感沮丧,并最终离开了游戏。在玩了10个小时的游戏后我便因为游戏体现出了过多现实的责任感和压力而放弃了游戏。

与之相反的是我会反复回到《我的世界》中,因为不管怎么看它始终都是一款出色的游戏。游戏中的每一个选择都具有自己的意义。它还拥有内在的环境设置,每一个行动的环境都将成为玩家开放性叙述的一部分。也许你的世界不会对其他玩家造成过多影响,但是你却能够始终面对着自己的故事而发展。选择环境已经深深嵌在玩家的游戏体验中,并且玩家选择所获得的奖励也将体现在各自的环境中。不管玩家做出何种行动都是有回报的。牺牲能够获得奖励,犯错能够获得奖励,就连漫步在偏僻的路径上玩家也能够看到更多不同的环境。

所以结果是怎样的?

我们几乎在任何一款游戏中都设置了相同的选择:奔跑,爬行,跳跃,射击,建造,收集道具等,而这也只是其中的一部分。《我的世界》对于我的控制主要是同时提供给我消极和积极的选择,就如建造是收集道具的一部分,Markus Persson中所呈现的情感控制总是非常有限,但是他却总能重新构思每个选择的意义。

只有当我们意识到我们所提供的选择具有情感空间,我们才能够真正打破更多情感束缚。

篇目3,游戏设计师应如何让玩家做出有趣的决策

作者:Jon Shafer

知识就是力量。但是游戏设计师却常常因为忽视了这句老话而陷入危险中。作为开发者我们总是希望游戏能够让玩家实现自己的幻想,但是通常情况下却都是游戏本身在阻碍这种实践。

不论是在游戏里还是生活中,我们总是会因为不清楚该做什么而感到不安。大多数游戏都会要求玩家做出各种选择,但是如果游戏不能够提供足够的信息帮助他们自信地做出选择,最终只会让玩家遭受挫败。

在本篇文章中我们将详细阐述信息在游戏中所扮演的角色,为何有意义的选择需要提供情境但是事实上我们却常常忽视这一点。我将通过列举一些例子进行说明,同时我们也将发现在某些特殊情况下,隐藏某些信息也能创造出更棒的游戏。

make decision(from phoenixdecisions.com)

有趣的决策

设计师的目标便是为玩家创造出各种有趣的决策。“有趣的决策”是指玩家拥有2个以上长期等价的选择。相反地,也存在两大因素将会导致游戏缺少乐趣——当一个选择比其它选择更加有利,及当选择的结果不够明确时。

如果玩家因为决策而感到困惑,那么他们面对选择的感受将会从矛盾慢慢转变为厌烦。如果游戏缺少情境,玩家便只能选择那些看起来最简单,听起来最酷,或者位于列表最前方的选择。如此玩家便不可能投入过多精力于这些抽象的选择中,而如果他们在之后发现自己的选择并不合理,他们也只会去责怪游戏而不是自己。

当玩家失败后他们便会想道:“我本应该选择X而不是Y。让我再试一遍看看能不能做得更好。”但是这也只会出现在玩家觉得游戏是公平的,且期待看到游戏最终结果的前提下。

如果你希望玩家能够做出策略型决策,那你就需要明确公开游戏机制。例如,一款游戏拥有可升级的装备,那么设计师就需要解释清楚装备武器后会出现何种结果。

告诉玩家他们的行动会造成多大的伤害,比告诉他们神秘且抽象的攻击加值为5有用得多。5代表什么?如果玩家使用的所有武器都带有单一的攻击值,那这便不是什么大问题;但是如果玩家必须从+5攻击武器和+7防御盾中做出选择情况又是怎样的?如果不能完全理解这些数值的含义,玩家又该如何比较武器所代表的值呢?

创造一些无知选择的主要问题还在于玩家很难对此提起兴趣。你可能已经熟悉于之前的武器每一发能够造成10点的破坏力,并且需要连击4次才能杀死怪物,但是当你购买了新武器,也就是每一击能够造成16点的破坏力并且只要连击2次便能够杀死怪物时,你可能会因为感受不到之前的那种刺激感而失去了游戏兴趣。

只有当玩家清楚游戏中发生了什么,游戏才算真正开始。从而玩家能够开始制定计划,并努力权衡短期和长期利益。如果游戏能够带给玩家这种程度的舒适感,玩家便会愿意更长时间地坚守于游戏中。

完整的信息

通常情况下提供给玩家尽可能多的信息总是非常有帮助,但是有时候这也会破坏了一款游戏。特别是当玩家拥有全面的信息,即了解游戏所有内容时。

Checkers(from amazingserviceguy.com)

西洋棋(游戏邦注:又称国际象棋或欧洲象棋,是一种二人对弈的战略棋盘游戏)便是一个很典型的例子,因为游戏的整个棋盘和所有棋子都完全暴露在玩家面前。也就是游戏并未隐藏任何游戏元素。

几乎每一款游戏都需要一些不可预知元素,而“纯粹的”策略游戏便是绝佳例子。通常情况下,这种不可预知元素总是来自其它玩家,不管是真人还是AI。如果玩家总是知道敌人下一步的行动,那么游戏的紧张感便会大大受影响!

那些缺少不可预知元素的纸牌游戏需要采取其它方法去创造新鲜感,而随机性便是一种非常合适的方法。玩家所熟悉的纸牌游戏都会使用一个随机的桥牌。因为如果玩家每次看到的纸牌顺序都相同,那么游戏的重玩价值也就微乎其微了。

然而也并不是只有那些未涉及人类玩家的游戏会受到信息完整性的影响。上诉提到的西洋棋最近便“解决”了这一问题——即如果双方玩家都未出错,那么游戏的最终结果便是平局。

在游戏中添加某些隐藏信息便能够有效阻止单一策略支配游戏的情况。在许多策略游戏的地图中总会覆盖着一层“战争迷雾”,而玩家就必须通过不断探索去揭开隐藏在黑暗中的秘密。

有时候甚至是地图本身也会随着时间的变化而变化。例如在最近的《文明》中,技术研究便能够揭示一些新的资源。它们的陡然出现将会很大地改变特定情境下的“完美”策略。而玩家需要不断适应前所未知的环境便是游戏中的一大乐趣。

在单人游戏中隐藏信息尤为重要。在大多数游戏中我们很难创造一个能够与游戏中的佼佼者进行较量的AI。而如果人类玩家能够清楚地掌握整个游戏局势,他最终也会了解AI的游戏模式,并无情地击败它。所以采用这种模式的游戏很快便会失去一时的乐趣和魅力。

游戏需要隐藏多少信息主要取决于设计师的选择和目标。纸牌游戏《Dominion》在每个环节的一开始便提供给玩家10张随机行动纸牌,玩家难以预见自己会收到何种排序的纸牌更是增添了游戏的重玩价值。

但是那些玩了好几遍游戏的玩家将会逐渐看清游戏的纸牌设定,所以便会觉得《Dominion》是一款刻板的游戏。虽然添加更多随机元素或隐藏信息能够完善这些玩家的游戏体验,但是与此同时却有可能剥夺了其它玩家的游戏乐趣。可以说比起科学,游戏设计更像艺术。

不完整的信息和风险

游戏的目标是确保有效地权衡每个决策。要么选择较小但却更安全的选择,要么选择风险较大但却作用性更强的选择。

一般来看这种做法总是很有效,因为安全简单的选择能够在短期内给予玩家回报,而具有长远作用的选择因为会带动其它元素发挥作用所以也更具有风险性。

如果一个选择只有“25%的成功概率”以及“75%的一般概率”,那么玩家肯定不愿意投机地做出策略性选择。

尽管这种决策有时候也很有效,但是仅凭一个只有50%的击中率以及50%的破坏力,或拥有90%的击中率但却只有25%的破坏力的武器,玩家实在很难做出有趣的决策。

通常情况下玩家总会做出一些安全的选择(特别是当他们做出一些大选择但却连续三次遭遇失败时)。在现代游戏中我们很少能够看到这种机制了,不过在一些日本角色扮演游戏中偶尔还能够看到它们的身影。

我们可以在一些体育团队管理模拟游戏(即带有长期玩家发展元素或受伤/新股弱势等风险)中找到相互作用的短期安全选择和持久风险选择。

在过去六个多月的时间里我一直在玩一款基于文本的模拟游戏《劲爆美国棒球》,并且在游戏中周旋于各种痛苦的决定——我是否应该在一个人还年轻,发展空间仍旧渺茫的前提下卖掉他?我是否应该以两个前景渺茫的包裹去换取一个较为安全的包裹?正是不能预计未来加上对于游戏机制的理解,某些前景发生概率的证明结果,玩家的伤病史,某些位置的价值等等结合在一起提供给了玩家非常有趣且复杂的决策。

这种权衡几乎可以使用在任何游戏中。我是否应该对邻居宣战?不知道我用于占领他们领土的资源是否会超过我所能够承受的范围?我们是否应该去攻击游戏中的任意boss并尝试着打开一个新的探索领域?虽然为了做出决策玩家必须知晓大量的信息,但是我们却不能低估不完整的信息所带来的积极影响。

例外

我知道有些人并不认同我所持有的这一观点,并宣称游戏需要的“不只是数字”。我从未反驳游戏值所带来的别样趣味。许多参杂了各种数字的有效设计方法也带给了玩家各种乐趣。而我们真正需要掌握的要点其实非常简单,也就是当提到游戏机制时我们能够同时感受到策略与情感的存在。

Dwarf Fortress(from gamaustra)

《矮人要塞》便是一款未与玩家过度分享游戏内容的典型游戏。游戏主要是关于探索游戏空间并让玩家在出现任何疯狂的事后放声大笑。尽管大多数玩家并不想面对喝药水的风险并因此而终止了游戏,但是还是有很多玩家会这么做,而开发者却不能取消这种设置。一般来看这也是roguelike类游戏所突出的一大特征——即一个小问题将会破坏一切。

每个开发团队都需要明确在策略vs.情感的范围中,他们希望自己在哪里着陆。游戏的目标是什么?谁是我们的目标用户?我们希望玩家在面对一些特定事件时有何感受?所有玩家都是不同的,所有游戏亦是如此。

结论

在游戏设计过程中设计师真正需要在意的是玩家的想法。你可以创造一个最酷,最复杂的系统模式,但是如果玩家根本不清楚游戏中发生了什么以及游戏情境中有何乐趣,那么所有的这些设置便都是徒劳。当玩家掌握了游戏机制以及它对自己决策的影响,他便能够将其转变成自己在游戏中最独特的体验——也就是这时候游戏才算真正走上成功之路。

篇目4,分析如何在游戏中设置有意义的选择

作者:Ben Serviss

游戏总是喜欢提供给玩家大量选择。可惜,大部分时候,玩家所面临的最终选择要么就是从饿狼那里救下无助的小羔羊,要么便是交由游戏决定,而不存在中间选择。

由于经常要从这种粗制滥造的‘选择’中做决定,所以精明的玩家总是能够轻松地揣测出之后的情节发展,并根据自己的经验做出相应选择。

这怎么能称得上是真正选择呢?尤其大部分游戏提供的选项均类似亚策略,即游戏设计师所谓的“按照自己路线”。无论该线路是良好还是混沌不堪,它都是你的通关路径。如果你想改变路径?那就尽管这么做,但在大多数《D&D》的奇幻世界中,玩家却很难做到这一点。

你已经明确了自己的玩法,虽然你可以改变这些既定观念,但你的选择只是关于游戏内部的改变,而非能够产生微妙结果的真实决策。

这听起来极其类似对现实选择的粗糙模仿。但这也正是其乐趣所在。假如:现在是清晨,你正准备上班。那么你是会打开大门径直走出去还是踢倒门后先探出脑袋?或是打破窗户,然后利用捆绑的被单滑下去?除非你是个特技人员或精神病患者,否则,你应该会选择打开房门,像正常人一样走出去,因为这属于最低必要的行动。

.jpg)

fable3(from gamasutra)

(Lionhead的《神鬼寓言3》力图为玩家呈现出有意义的选择)

其实我们在某一天内做出的所有决定,或‘选择’,仅仅只是自己为了完成某些事物的最低必要行动。

需要注意的是,关于最低必要行动的定义会根据不同的变量而发生改变:包括你的性格和品行,目前心态以及当时所获得的有效信息。如果在你准备上班的那个早晨,你发现房子着火了,你便会径直跳出窗户,逃离那里。但如果你并未闻到烧焦味呢?你可能就会和往常一样平静地走出大门。

(游戏邦注:简而言之,如果某些事情阻碍了你,你便会加强最低必要行动——这是让人紧张的高潮部分,是形成任何媒介中出色故事情节的核心。)

在此,我要阐明的是,你在生活中做出的每个‘选择’都是基于这些变量,它们最终会促使你做出当下的最佳选择。

所以你在现实生活中所做出的选择并不属于技术选择,反而更能呈现出你当前的品性、心态与所获得的信息——那我们该如何在游戏中制定有意义的选择呢?

其中一种方法便是通过摆脱枯燥的逻辑而挣脱出色/糟糕/中立等亚对策限制,脱离完全枯燥的逻辑形式。Molleindustria的《Unmanned》便是该方面的典范。在该游戏中,你会扮演一个在美国远程操控阿富汗地区无人机巡逻战役的控制员。其核心玩法便包含了各种选择,从最世俗的问题到生与死之间的选择等等。

我们不需要始终清楚地呈现出每个选择的结果,偶尔的模糊感反而更加接近现实生活。总之,我们在《Unmanned》中看到的选择几乎都与产业的传统理念相背离。

如果更加精美却详细的画面与日益复杂的机制是用于衡量技术发展的主要元素,那么,更加模糊的选项则能帮助游戏传达出更加复杂的情感。

篇目5,关于游戏是否是关于玩家选择的问题探讨

作者:Warren Spector

如果说有什么是每次关于游戏叙述讨论中都会出现的内容,那便是玩家的选择。

有时候,如果游戏是基于分支故事结构,那么选择可能会取决于游戏系统或机制(就像Telltale和Quantic Dream等公司采取的做法)。

有时候,在一款带有更加开放结构的游戏中,选择可能会通过玩家与模仿元素,系统和机制间的互动进行传达(就像Bethesda和Bioware等公司采取的做法)。

幸运的是最终所有人都能够沉浸于游戏中—-特别是叙述游戏。

几乎所有人都同意选择作为定义游戏玩法特征的重要性,但是也存在一个陷阱在引诱着我们:

简单地说来,游戏不是,更确切地说是不应该是关于选择。

更具体地来说是,我们应该把握两大理念:

首先,选择理念是最重要的,不管是就其本身而言还是基于媒介的本质。

其次便是选择所蕴含的理念,这甚至要求我们基于奖励和惩罚,更好与更糟,正确和错误,明亮与黑暗,好与坏等角度进行思考。

我并不是只有这种想法。我并未只是专注于选择。我也未沉迷于受选择所推动且带有相对关系的游戏。

选择。并不。重要。

相对关系是无聊的。

没有结果的选择是无意义的。如果它们并不会创造出不同的结果(游戏邦注:即从根本上看来完全不同的结果),那又有啥意思呢?

鼓励玩家基于对与错进行思考的游戏其实是在鼓励玩家“按照标准游戏”—-就像“喔,我是坏人,现在的我拥有一些恶魔的标志!”或者“喔,看到了吗?我带有天使的翅膀和光晕!”而这一切都非常荒谬。

你可能会想:“等等,你是不是那个已经抱怨着玩家选择好几十年的人?”

不,我并不是这样的人。如果你仔细思考我所说的,你便会发现选择并不是一切。它并非我们中的某些人所谓的“共享资源”的关键。

所以我到底是在抱怨什么呢?

玩家选择的有趣方面并不是关于选择本身。真正有趣(也是唯一有趣的点)的是结果所揭露的内容。所以说没有结果的选择都是在浪费时间,努力和金钱。

right-wrong(from dreamstime)

但等等,“结果”这个词难道不代表惩罚吗?即将我们带回更好/更糟,好/坏,对/错的选择中?难道结果不会要求设计师去利用价值判断或提供好/坏的指标从而让玩家清楚自己的立场?

并不是这样的。

我为我们团队所列出的一个固定规则便是“永远不要去判断玩家。”玩家永远不会知道你是如何思考一个问题或者问题的答案。你并不是为了回答你让玩家去考虑的问题而存在。我让我的设计师们清楚地告诉玩家“什么是对的以及什么是错的”。设计师的存在是提供给玩家测试行为的机会然后去观察这些行为的结果。基于机会,玩家会自己判断做出特定选择的利益是否有价值。

根据我的经验,有一些问题或情况通常是基于正确或错误的答案或解决方法进行定义。即使你不认同,我也会说最有趣的情况便是在对与错之间的差别不明显的时候。我并不理解为什么越来越多游戏开发者不承认这点并沉迷于我们的媒体对于我们所生活的奇妙且缺少透明度的世界的反应能力。

完整的循环

让我们尝试着将这两部分内容带到完整的叙述循环中。让我们假设这是关于问题,选择和游戏叙述的本质:

一款成功游戏的叙述并不是在讲述一个吸引人的故事(尽管这很明显是可取的!)。

一款成功游戏的叙述是会询问问题的。

一款成功游戏的叙述会提供给玩家回答局部(当下)和全局(整体故事的发展)问题的工具。

一款成功游戏的叙述会呈现给玩家他们局部和全局决定的结果,并且不会判断玩家为何会做出这样的决定。

所有的决定都有其代价和利益。这里不存在绝对的对与错。即使你不认同,能够反应人们意愿的游戏都能够让玩家基于其它媒体所做不到的方式进行思考。

一款成功游戏的叙述能够创造不只是关于每个玩家如何解决一个游戏问题,还关于为何这么做的对话。我们在游戏中所听到的大多数对话都是关于最佳策略或者如何移动一个过场动画。想想都觉得这很无聊。

我希望(并且也希望你们希望)听到玩家去讨论他们的决定的对与错。我希望听到一个玩家说:“你怎么能够偷窃?”而另一个玩家在描述他的心理过程。我希望听到一个玩家问:“为什么你在那个人那么做之后还留给他生路?”而另一个玩家列举了像甘地和平主义例子进行说明。我希望听到因为自己的选择而到达最终游戏的玩家能够问另一个玩家:“你怎么能认为解决方法是适当的,正确的或者符合道德的?”

“适当的”,“正确的”和“符合道德的”都是一些神奇的词。其它媒体可以宣称它们也能够处理这些概念,但在那些媒体中,这些词是属于作者,而在游戏中,这些词则是属于玩家。

综合上述所有内容,我们将逐渐意识到游戏作为一种独特的叙述形式所具有的潜能。显然我们对于早前的叙述模式有所亏欠,但现在我们可以也必须基于所学到的内容去创造比其它媒体更协调,更感人且更加吸引人的内容。

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4,篇目5(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

篇目1,Meaningful Choice in Games: Practical Guide & Case Studies

by Brice Morrison

I’ll never forget Boyd. May he rest in peace.

Boyd was my mate, my friend, my confidant. I trusted him and he trusted me. But in a difficult spot on the battlefield in Fire Emblem, I realized that Boyd wasn’t going to make it. He was cornered by knights, no way out. And after a few more turns, the damage was done. The character I had since the beginning was killed.

I felt terrible. Awful. He didn’t have to die – the game didn’t have any requirement that he not make it through the battle. It was my fault, needless bloodshed. He was a good, strong character with some good weapons and armor, but now he was gone.

Throughout the rest of the game I was reminded of my mistake. His brother would say, “We can do this! It’s what Boyd would want.” His friends would chime in, “If only Boyd were here, he’d know what to do.” I’d go into battle thinking how useful he would be, but he was gone. Heck, this game is almost 10 years old now, and I still remember it, despite not remembering the name of a single other character in the game.

My experience with Boyd, a virtual character afflicted by a virtual choice, taught me as a game designer what it is to create a “meaningful choice” in a game. Choices that pull at players heart strings, that make them look deep inside themselves at their own character in real life, that they remember as deeply emotional experiences. These are the designs that turn a game into art.

But how do you do it? How do you make a choice in a game truly meaningful?

Rather than take my word for it, let’s learn from the masters – 2012’s critically acclaimed Walking Dead, which I personally believe that this game is the current state of the art.

What Is Meaningful Choice?

This is one of those “are games art?” type questions that everyone has an opinion on and discussions go on forever. That’s fine, there’s room for opinion.

But for my designs and for this article, I define meaningful choice very specifically.

Meaningful choice requires the following four components:

1.Awareness – The player must be somewhat aware they are making a choice (perceive options)

2.Gameplay Consequences – The choice must have consequences that are both gameplay and aesthetically oriented

3.Reminders – The player must be reminded of the choice they made after thay made it

4.Permanence – The player cannot go back and undo their choice after exploring the consequences

If all four of these requirements are satisfied, then we have a recipe for meaningful choice. The reason that this is true is that these are the components of a meaningful choice in real life.

Think of the big decisions you made in your life – where to go to school, whether to tell on your friend, who to marry, whether to break up – all of these choices have these four components. And these are the choices that make up our lives.

In games, choices with these components will evoke a strong emotional reaction, something that players discuss and think about and remember. By making the choice meaningful, we help to make the game itself meaningful.

Let’s step through each of these four components in detail.

Component 1: Awareness

If the player isn’t aware they are making a choice between two or more options, then it isn’t meaningful.

Imagine that a player is in a game where a character named Cindy is crying for help. The player runs over and helps Cindy. At that moment, the game says, “You choose to save Cindy instead of Bernard.”

But the player never saw Bernard. They didn’t even know Bernard was in trouble, or that he even existed. At this point, the player would probably feel frustrated. This ruins the choice and makes it meaningless. Instead of feeling responsibility for any consequences of the choice of Bernard vs. Cindy, the player will instead blame the game. “What?! I didn’t know I could save Bernard! I didn’t even want to save Cindy!” It’s no longer viewed as any kind of choice, and anything that happens as a result will be viewed as inevitable.

Second, the player completely misses the experience of having to think, agonize, and decide what they would like to do themselves instead of what the game is telling them to do. If the player isn’t aware they are being presented with a choice,

The Walking Dead handles the awareness of choice through its choice interface largely pioneered by David Cage in his games Heavy Rain and Fahrenheit. Most of the time when a player is presented with a choice, they can clearly see the other options.

Exactly how much awareness you give the player is up to you.

In the Walking Dead, some choices and their consequences are obvious. A situation very similar to the example above, the player is hiding out from the walkers in a convenience store. A group of walkers breaks into the store and two characters are grabbed, and the player must choose who to save.

The player is given plenty of time to make this choice, and both characters are in the player’s field of view. This makes the fact that it is a choice obvious, so when the player picks one, they feel responsible.

The level of awareness of a meaningful choice can vary, however, long as the player knows they are making an explicit choice.

As an example, In a conversation with Hershel at the beginning of the game, the player is asked a number of questions, “Where did you guys come from?” “Are you her father?” “Who did you come here with?” It isn’t exactly clear which of these questions are significant and which aren’t. However, the player is still aware that they are making choices, even if they aren’t sure what the consequences will be. The interface for conversation makes this clear – the player is never presented with one response – always two or more.

So when Hershel catches you in conversation or in a lie, then the the player feels like it was their fault. They saw that they could say, “I was alone” versus “I was with a police officer”, and so when Hershel reprimands them, they know that it was their decision.

Component 2: Gameplay Consequences

Imagine you’re playing a game and you get a treasure chest. Inside the treasure chest there are two items:

1.A new sword that is more powerful and will defeat two-hit enemies in just one hit

2.A sword that acts the same, but it’s a different color than your current sword

Which would you want? Obviously you would want the first sword, because it has gameplay consequences.

Gameplay consequences don’t just change the signs and sounds of the game, they actually change the behavior and actions of the player. They don’t just make the game look different, they make it act differently.

The best meaningful choices have both aesthetic AND gameplay consequences. Changing the experience of the game, the behavior of the player, is typically more meaningful than just playing the same game with different set dressing.

In the Walking Dead, there are numerous gameplay consequences from the player’s choices. Deciding to back up Kenny in a fight he’s having with Larry affects how he feels about you. In a fight in the convenience store, backing up Kenny means that later he helps you when you get into a scuffle with Larry. It also affects whether or not he decides to go along with your plans.

True to the premise of the games, the choices you make have ripple effects until the final episode is complete.

For a poor example of gameplay consequences, one of the more recent games in a narrative genre dealing with meaningful choice was David Cage’s Beyond Two Souls. In contrast to the critically acclaimed Heavy Rain, Beyond Two Souls drew scorn from many players and reviews (Score of 71 Metacritic, versus 87 for Heavy Rain and 92 for Walking Dead). While the graphical effects were phenomenal, the gameplay seemed by many to be lacking.

Kyle Orland from Ars Technica wrote:

I rarely if ever stopped to consider a choice in Beyond: Two Souls…Instead, I mainly sleepwalked through a seemingly endless sequence of practically preordained story beats, struggling to care as I was dragged through a clichéd plot with no sense of meaningful agency.

Making a choice of whether to talk about Ellen Page’s dress versus the guests has no result other than changing the dialog for that line. The rest of the game is the same.

By using the framework for meaningful choice, we can make a hypothesis of what was wrong with many of the choices in Beyond Two Souls: they didn’t have strong enough gameplay consequences. While it’s all conjecture, perhaps if the team at Quantic Dream had improved this, maybe the decisions players made would have felt like they had greater emotional weight.

Component 3: Reminders

Regret is a very complex human emotion. The regret of letting old friendships slip away. The regret of having worked too much and not spent enough time with family. The regret of having never went for your dreams when you had the chance. Regret is the combination of disappointment and responsibility, the sadness that comes from the present not working out as you wanted because of choices in the past.

Pride is the opposite of regret. Pride is when you feel elated because of a choice you made that has resulted in the outcome you wanted (or better). It’s being proud that you decided to marry the person you love. It’s being proud that you chose one job that turned out great. It’s being proud that you made the right decision.

These stories of regret and of pride are the stories that make up our lives.

However, if you don’t remember your previous choices, then you will never feel pride or regret. Or if your previous choices don’t affect your present world, then you will similarly not feel anything.

In Walking Dead, the player is constantly reminded of choices that they made in the past. “You never backed me up!” yells Kenny. “You weren’t able to protect her at the Motor Inn”, says another character later on in the game. The choices that you make not only affect the moment, but the long term relationships that you have with other characters. If Telltale hadn’t put these reminders in, then many of the choices would have meant nothing to the player.

By sprinkling reminders through the game of what choices the player made previously, the choices take on more and more weight. As the player goes forward in time the same old choice affects more and more of their experience, imbuing it with meaning. If you made your choice and then went on without even remembering it, you would never later feel regret or pride. You’d just feel nothing.

Component 4: Permanence

At the end of Paper Mario and the Thousand Year Door, the final boss asks Mario if he would like to turn evil and join their side. The player can choose yes or no.

If you select yes, the final battle commences. However if you choose no, then the player simply gets a “Game Over” screen and is reset about ten seconds backward.

No one talks about this as being an incredible ending that reveals something about your own moral fiber. If they remember it all, they talk about it being annoying. The fact that you can go back and change your outcome immediately turns what could be interesting gameplay into a boring formality.

The reason that choices in real life are so fraught with emotion, with sadness, with purpose, is because they are permanent. We can’t live our lives over again. In real life, you can’t have a fight with your significant other and then rewind and do it again. You only get one shot, which is why you need to choose your words and actions very carefully.

And yet in games where you can reset, you have no problem blowing up buildings or attacking innocent bystanders with no hesitation.

Walking Dead handles this by using autosave functionality. As soon as the player makes a significant choice, the game locks it in so that they cannot go back. Thus, with every choice you make, you need to be sure it’s what you believe.

Sure, players could restart from the beginning or reset the episode, but the added inconvenience is usually enough to deter them.

Conclusion

I hope this framework is useful to others. If you can make sure your choices in games have all four components, then I believe they will carry enormous value to players.

As I mentioned earlier, there are likely thousands of variations and permutations on how to create meaningful choice, this is just one that has been helpful to me that I see over and over again in successful games.

I do believe that games are art, and the deeper games can probe into emotions normally reserved for film and literature, the better. By making games that cause players to make choices that cause them to evaluate their character as a person, to take the lessons of the game and apply it back to their real lives, we as game developers will have done something very special.

篇目2,The Power of Choices

by Randy OConnor

It’s been suggested that true games give the player rather than the designer power over emotion. But I don’t believe that’s true. It’s how much choice we give players, what that choice affects, and how the choice is resolved that gives us as designers power over a player. We present choices, and the manner in which we do so determines how they will emotionally respond.

The Interaction

First there is the player-system interaction. For example, a racing game is heavily about player-interface-interaction. The choices are about mastering the system to a desired outcome. The choice lies not in deciding what to do, but how to do it, and the emotional power of this design is in the mastery of a system, knowing what is the right choice and being able to choose correctly.

The designer chooses how to challenge this mastery, but Call of Duty employs the same emotional design principals as racing. Mastery of the system, knowing and learning how to correctly interact creates a certain player response, it allows players to feel pride, exhilaration in those moments of choice, or anger at oneself for failing to master technique. Can it possibly create more emotional response than that?

This mastery of systems includes other games like Starcraft, wherein any great player learns hotkeys, learns what to build first, necessary techniques that open up more choices further in the game, choices that in Starcraft are still limited by the necessity of victory.

The Breadth of Choice

This is how the choices we make mean within the overall systems of the game. There are narrative systems and object interaction systems, these are the two functional game elements, and both of these systems are important if the designer so chooses. The narrative is the context and aesthetic, the object-system-interaction is the functioning of the pieces within a game. This is how much choice we give a player over the systems that run a game and what the style of that choice is.

Object-level-interaction is the choice of the player on how they alter their world. A Lucasarts adventure game is usually about discovering the depths of the wordplay, the disparate objects and their uses. The inspect, open, and talk are equivalent to the shoot, pick up health, and strafe of a shooter. Schafer or Gilbert or another is working at an object interaction level where the objects are about creating emotion and laughter. Reading a line of dialog in Monkey Island lets you see the humor of the line and gives you the choice to even go further and see what that line means within the system, but reading the line alone is the power of an adventure game writer.

And therein lies the power of the designer. In an adventure game, how often are you given the choice to punch a character? Is that a function that makes sense within the system? The choice to not let you do anything but walk and talk and use miscellany to progress the story is a specific adventure game choice that seems almost necessary because it’s so common.

Genres grow up around these concepts of presumably stable and clear systems. I have compared Waking Mars to Metroid in world structure to some people, because that’s what they understand, but it’s a grossly inappropriate comparison in every other regard.

Shooters all have cover systems now, because that’s just what you do, it’s a system that has been agreed upon. I have mentioned multiple times that I’d like to see more done with wider physical interaction systems. Have people made games where you fumble with your ammo clip, where handling your equipment is as complicated and taxing as shooting? Far Cry 2 has your guns jam, to make the guns themselves mean a little more, but did it go much deeper? If you made me fumble with reloading, you would create different emotional cues that might go in new directions. We have reached the end of the line on shoot or don’t shoot, we know the extent of that emotional power.

How about Sim City, the creation and destruction of cities, the breadth of our choice. It’s creativity and destructivity, and upkeep, choices we make not with a goal of forward movement through a linear story, rather choices Wright made that asked what you wanted, and what will you do to keep your dreams afloat. Is it possible even to do so?

And the Context of Choices is the great frontier of game designing emotion.

The context of choice is this idea that what we do within a game means or doesn’t mean something. There are positive/creative choices, there are negative/destructive choices. There is the lack of choice when we want choice, there is too much choice when we’re tied down to a narrow context. Sim City has some scenarios to give context, but often it’s about creating our own.

Dys4ia by Anna Anthropy is great, and I love it exactly because it seems to me that the designer has chosen to limit your choice within the context of the story. You have these chapters you can play in any order, sure, but life itself when you get to the living of it, we can’t help what happens. Whenever we’re given any power and control at all along the path it is almost surprising. The “choice” of taking your pills is jarring, and how much choice, I wonder, do we really have?

GTA IV bothered me because the context said that I had no choice, and yet the system was wide open. I would be joyriding and ignore a call from Lil Jacob only to see a little thumbs-down appear for ignoring him. I felt like I was punished for embracing the over-arching systems the game encouraged. There was so much story to go through, they didn’t want me free-roaming the city. Their story wasn’t dynamic enough to uphold the beautiful and expansive and physical Liberty City. The context of my choices pushed me away from that game, disheartening me. I dropped the game because after 10 hours they had too successfully captured the responsibilities and pressures of real-life, and I didn’t care anymore as I had with GTA 3.

And I always return to Minecraft, because it’s always so beautiful as the example. Every choice means something. It has internal context. The context of every action builds into an open narrative that is yours. Your world may not mean much to someone else, but that chip in a stone wall you made digging some coal to create a torch has a story. The context of a choice is internal to you, yet the game rewards play by making every choice reflected in your environment. Everything is earned. Sacrifices are rewarded, mistakes are rewarded, wandering off the beaten path shows you all the more environment that you might get the urge to affect.

So What?

We give the same set of choices in almost every game we make: run, crawl, jump, shoot, build structure, collect item, but that’s only a part of it. Minecraft’s power over me is that the choices are often both negative and positive, build structure is part of collect item, and the emotional control that Markus Persson exercised over his game was limited, but he reimagined what those choices mean.

We can break so many more emotional boundaries if we recognize that the choices we give create emotional spaces. It’s not enough to shoot or not shoot. Have we ever actually let the player put down their gun and start TALKING to the enemy? Will we ever give Gordon Freeman not only a crowbar but a voice?

篇目3,The More You Know: Making Decisions Interesting in Games

by Jon Shafer

Knowledge is power. Game designers ignore this old adage at their own peril. As developers we want our games to empower people to live out their fantasies, but all too often the games themselves get in the way.

Whether in games or in life, we’ve all experienced that uncomfortable feeling of having no idea what to do. Most games require players to make a vast number of decisions, and if they’re not provided enough information to make those choices confidently, the end result is nearly always frustration.

In this article we’ll examine in detail the role of information in games, why meaningful choices require context and the consequences of omitting it. We’ll also look at a few examples of how, in unique cases, hiding some things can actually make a game better.

Interesting Decisions

A designer’s goal is always to make every decision the player faces interesting. An “interesting decision” is when a player has two or more options which are (roughly) equal in value over the long term. Conversely, there are two main factors which can make decisions uninteresting: when one option is clearly better than all others, and when the consequences of the options are unclear.

If someone is confused by a decision, their feelings toward the choice will range from ambivalent to annoyed. With no context, they’ll simply choose the option that is easiest, sounds coolest, or (gulp) is first in the list. It’s impossible to be heavily invested in such arbitrary decisions, and if the excrement hits the fan later on, they’re much more likely to blame the game than themselves.

After people fail, the goal should be for them to think, “Dang, I really should have chosen X back there instead of Y. Let me try again and see if I can do better.” This only happens if players feel like the game was fair and sufficiently prepared them for what was to come.

If you want players to really be making strategic decisions, then the mechanics of the game need to be laid bare. For example, a game with upgradeable equipment needs to fully explain the consequences of equipping a weapon.

Knowing how much more damage you’ll be doing is much more useful than being told the player’s mysterious and arbitrary attack value is increased by 5. Five what? It’s not a big deal if all you’re dealing with are weapons with a single attack value, but what if you have to choose between a +5 attack weapon and a +7 defense shield? How does one compare their value without a full understanding of what these stats actually mean?

Another major issue with making uneducated choices is that it’s hard to get excited about them. You feel a real sense of progress knowing your old weapon did 10 damage per swing and could kill those monsters with four hits, but that new one you bought does 16 per hit and can kill them with only two swings. Just knowing that now you’ll do “more damage” doesn’t provide quite the same thrill.

When you know exactly what’s going on, that’s the point at which a game really takes off. This provides the opportunity to start making plans, and the trade-off between short-term and long-term interests becomes a very tough call. If players are able to reach this level of comfort, they’re likely to stick with a game for the long haul.

Perfect Information

While providing players with as much information as possible is usually ideal, there are situations when it can hurt a game. One such case is when the players have perfect information — that is, they know everything there is to know.

A good example is the game checkers, where the entire board and all pieces are visible. There are no elements of the game itself which are hidden from either player.

Nearly every game needs some element of surprise, and “pure” strategy games are the best example. In many cases, this element is provided by other players, be they human or AI. If you always knew exactly what your opponent’s next move was, there wouldn’t be a whole lot of tension!

Solitary games that lack an unpredictable opponent need some other way of spicing things up, and some form of randomization is virtually always the answer. The solitaire card game that nearly everyone is familiar with uses a randomized deck. If the card order was the same every time, there would be almost zero replayability.

However, it’s not just the games without human players that are seriously damaged by perfect information. The aforementioned checkers was recently “solved” — meaning if neither player makes a mistake, the end result will always be a draw.

Having some form of hidden information is a crucial element to preventing a single strategy from dominating. In many strategy games, there is a “fog of war” which covers the map, and exploration is necessary to reveal what lies in the darkness.

Sometimes even the map itself changes over time. For example, in the recent Civilization games, technological research reveals new resources. Their sudden appearance can greatly alter the “perfect” strategy for a given situation. This constant need to adapt to previously unknown circumstances is a big part of what makes games fun.

Hidden information is especially important in single-player games where AI opponents are simply executing lines of code written by a human programmer. In most games it is nearly impossible to develop an AI that will compete with the best of the best. If the human player is also able to see the entire game situation clearly, it’s only a matter of time before the AI’s patterns are learned, dissected and ruthlessly exploited. A game solved in this manner quickly loses whatever charm and joy it once held.

The amount of information that “should” be hidden can vary greatly, and ultimately depends on the preferences and goals of the designer. The card game Dominion makes 10 random action cards available to players at the beginning of each play session, and the inability to predict the order in which cards are drawn provides a great deal of replayability.

However, those who have played enough games will begin recognizing the optimum strategies for a given set of action cards, and Dominion has become formulaic for some. Adding more randomization or hidden information would probably improve the game for these players, but it might also make it less enjoyable for others. Hey, game design is more art than science.

Imperfect Information and Risk

The goal is to require some form of trade-off with every decision. One example of this is choosing between a smaller but safer bonus, and a riskier but much more powerful one.

This generally works best if the safer bonus is safe simply because it pays off in the short term while the other option pays off later and is riskier because other factors can come into play.

If the choice is basically just between “25 percent chance something really good happens” and “75 percent chance something okay happens” you’re not really making a strategic choice as much as you’re gambling.

While this can be made to work, it’s tough to make an interesting decision out of swinging a large weapon that only hits 50 percent of the time but does 50 damage or using one that hits 90 percent of the time and does 25 damage.

More often than not players will go with the safer option (especially if they try using the big one and it misses three times in a row — good luck getting them to try using it again!) This sort of mechanic is fairly rare in modern games, but I still see it pop up in a few Japanese RPGs.

You can find good examples of short term safety versus longterm risk working really well in pretty much any sports team management sim where there is a longterm player development aspect or the risk of injury/underperformance.

Chrono Cross

I’ve been playing a lot of the text-based sim Out of the Park Baseball for the last six months or so, and there have been some agonizing decisions — should I trade this guy in his prime for a collection of younger, less-developed and much riskier prospects? Do I send off a package of two risky prospects in exchange for one safer one? The inability to predict the future coupled with an understanding of the game’s mechanics, the likelihood of certain types of prospects panning out, the players’ injury history, the value of certain types of positions, etc. all combine to provide a set of very interesting and very difficult decisions.

This sort of trade-off can be applied in nearly any game. Should I declare war on my neighbor, hoping that the resources I expend to capture their lands add up to less than what I stand to gain? Is it worth the risk to attack that optional boss and try to open up a new area to explore? Players need to be equipped with some measure of information for this to be possible, but don’t underestimate the positive impact imperfect knowledge can provide.

The Exceptions

I know some people disagree with me on this topic and claim that a game needs to be “more than just numbers.” You won’t find me arguing against the value flavor and “feel” provide. There are an innumerable number of valid design approaches that can result in a game enjoyed by a large audience. The point is simply to recognize that when it comes to game mechanics there’s basically a scale that has strategy at one end and flavor at the other.

One great example of a game which definitely doesn’t go out of its way to share everything with the player is Dwarf Fortress, which is all about exploring the game space and laughing as all sorts of crazy things happen. While most players don’t like there being a risk of drinking a potion and the game permanently ending right then and there, there are absolutely some who do and we developers definitely shouldn’t write them off. The roguelike genre in general is characterized by this possibility of a single mistake derailing everything.

Dwarf Fortress

Every development team has to decide for itself where on the spectrum of strategy-vs-flavor it wants to land. What is the goal of the game? Who is our target audience? What do we want players to feel when certain events happen? No gamer is the same and no game should be either.

Conclusion

A point I often make when discussing game design is that the only manner in which a game really matters is inside the player’s head. You could have the coolest, most complex system modeling some really interesting phenomenon… and it’s completely irrelevant unless the player knows what’s going on and how to have fun with the situation. When someone understands the mechanics and the implications of their decisions and is able to translate that into a completely unique experience — that’s when a game really succeeds.

篇目4,The Fallacy of Choice (In Games and Real Life)

by Ben Serviss

The following blog was, unless otherwise noted, independently written by a member of Gamasutra’s game development community. The thoughts and opinions expressed here are not necessarily those of Gamasutra or its parent company.

Games love to make a big deal about choices. Unfortunately, most of the time your only options boil down to either saving the helpless baby lamb from starving wolves or punting it to the pack leader, with nary a shade of gray in between.

With such shoddy ‘choices’ to pick from, any savvy gamer can easily size up the predictable ramifications for later gameplay, then depending if he’s playing through as a saint or a shithead, make the corresponding selection.

How is this really a choice? More than anything else, choices in most games resemble a metagame that game designers play called something like “Stay in Your Lane.” Lawful Good, here’s your lane. Chaotic Bad, here’s your lane. Want to switch lanes? Go right ahead, but in most of these D&D wannabees, there’s simply no option to carve out a mixed path.

You’ve made your decision about how you’ll play, and though you can stray or even change philosophies, your choices amount to on/off switches throughout the game as opposed to real decisions that ripple out nuanced consequences.

Sounds like a pretty poor imitation of what real life choices are, right? Here’s where it gets interesting. Take this hypothetical scenario: It’s early in the morning, and you’re getting ready to go to work. Do you open the door and walk outside? Kick it down and leap out head first? Break the window and rappel out with tied-together sheets? Unless you’re a stuntman or a psychopath, you open the door like a normal person because it’s the minimal necessary action to take.

Think about it – all of the small decisions, or ‘choices,’ that you make in a given day are simply the minimal necessary actions needed to accomplish what you want to do.

Note that the definition of minimal necessary action can fluctuate wildly based on a few key variables: your overall character and morals, current mental state, and the information available to you at the time. If the morning you got ready for work, you discovered your house was on fire, then damn straight you’d bust out the window and get the hell out of there. But if you couldn’t smell the smoke yet? You’d walk out calmly like any other day.

(Aside: Simply put, if something gets in your way, then you step up the minimal necessary action required – this is the heart of dramatic tension, and the core to good storytelling in any medium.)

What I’m trying to say here is that every ‘choice’ you make in your life is simply based on these variables, which combine to point you to what amounts to the best choice at the time.

So if your choices in real life are not technically choices but more like confirmations of your character and morals, mental state, and information at the moment – how do we make choice meaningful in games?

One way is to break the constraints of the good/bad/neutral metagame by opting out of such bland logic completely. Molleindustria’s Unmanned is an excellent example of this. In the game, you play as a US-based remote operator for an unmanned combat drone patrolling in Afghanistan. Core gameplay consists of choices that range from the mundane to life or death matters, but always in the removed setting of the pilot who is never in danger himself.

Outcomes for each choice aren’t necessarily clear, and the results come across fuzzy – kind of like in real life. In a way, your choices in Unmanned are almost a reverse of what the industry typically considers cutting edge.

If sharper, more detailed graphics and increasingly complex mechanics are a measure of technical progress, then maybe fuzzier, murkier choices are the way to bring more sophisticated emotions to games.

篇目5,Another Narrative Fallacy: Games are About Choice

by Warren Spector

If there’s one thing that comes up in all discussions of game narrative, it’s the desirability of player choice.

Sometimes, if a game is built on a branching story structure, choices may be offered independent of game systems or mechanics. (See Telltale, Quantic Dream and others.)

Sometimes, in a game with a more open structure, choices may be expressed through a player’s interaction with simulation elements, systems and mechanics. (See Bethesda, Bioware and — finally… thankfully… – many more).

Happily, finally, everyone involved in games – especially narrative games – gets all that.

However, even with nearly everyone agreeing on the importance of choice as a defining characteristic of gameplay, there’s a trap waiting to ensnare the unwitting:

Simply put, games aren’t, and shouldn’t be, about choice.

To expand on that a bit, it’s important, I think, to get past two widely held beliefs:

First is the idea that choices are of paramount importance, in and of themselves, and by virtue of the nature of the medium.

Second is the idea that choice implies, even requires us to think in terms of, reward and punishment… better and worse… right and wrong… light and dark… good and evil.

I simply don’t get this kind of thinking. I don’t get the exclusive focus on choice. I don’t get the seeming obsession, in choice-driven games, with binary opposition.

Choice. Doesn’t. Matter.

And binary oppositions are boring.

Choices without consequences are meaningless. If they don’t lead to different outcomes – preferably radically different outcomes – what’s the point?

And games that encourage players to think in terms of right and wrong ultimately encourage players to, as I put it, “play the meter” – “Ooh, I’m evil and now I have horns and a bunch of demon tattoos!” or “Ooh, I’m good – see? I have angel wings and a halo.” It’s just ridiculous.

“But wait a minute,” you may be thinking. “Aren’t you one of the guys who’s been screaming about player choice for a couple of decades?”

No. I’m not. If you look closely at what I’ve been saying, choice isn’t the be all, end all. Not at all. And it isn’t the key to what some of us have been calling “shared authorship” all these years.

So what the hell have I been screaming about?

Here it is: The interesting aspect of player choice isn’t the choice itself. The interesting thing – the only interesting thing, really – is the revelation of consequences. Choice without consequence is a waste of time, effort and money.

But wait, you say. Doesn’t the word “consequence” imply punishment, which sends us right back to better/worse, good/evil, right/wrong? Doesn’t consequence require designers to impose a value judgment and maybe even provide a good/evil meter so players know where they stand?

Not at all.

One of the hard and fast rules I lay out for my teams is “Never judge the player.” Never. Players should never know what you think about a question or its answer. (See, this is where my last blog post about about questions comes in.) You’re not there to answer the questions your game asks players to consider. You’re most assuredly not there, I tell my designers, to say to players “this is right and that is wrong.” Designers exist to provide opportunities for players to test behaviors and then see the consequences of those behaviors. Given the chance, players will judge for themselves whether the benefits gained by making a particular choice were worth the cost of making it.

It may just be me, but in my experience, there are few, if any, questions or situations that lend themselves to clearly defined, universally agreed upon right or wrong answers or solutions. In most real world cases, there are only shades of gray. Even if you disagree (as extremists and believers of all stripes might) I’m comfortable saying that the most interesting situations are the ones where right and wrong are not readily apparent. I don’t understand why more game developers don’t acknowledge that and revel in our medium’s unique ability to reflect the wondrous, complex lack of clarity of the world in which we live.

FULL CIRCLE

Okay, so let me try to bring the two parts of this trip down narrative lane full circle. Let me close by saying this about questions, choices and the nature of game narrative:

A successful game narrative isn’t one that tells a great story (though that’s obviously desirable!).

A successful game narrative is one that asks questions.

A successful game narrative gives players the tools to answer those questions both locally (in the moment) and globally (in how the entire story plays out).

A successful game narrative is one that shows shows players the consequences of their local and global decisions, without judging players for making those decisions.

There are only shades of gray and, that being the case, all decisions have costs as well as benefits. There is no absolute right or absolute wrong. (And, yes, I’m a moral relativist at heart…) Even if you disagree, games that reflect that will get players thinking in ways no other medium can match.

A successful game narrative is one that engenders conversations not only about how each player solved a game problem, but also why. Most of the dialogue we hear around games is about optimal strategies or about how moving a cutscene was. How limited and dull that is.

What I want – and hope you want – is to hear players debating the rightness or wrongness of their decisions. I want to hear one player say, “How could you have stolen that?” and another player describing her thought process… I want to hear one player ask, “Why did you leave that guy alive after what he did?” and another make a case for Ghanndi-like pacifism… I want to hear players who reach an endgame driven by their choices ask one another, “How could you think that solution was appropriate or right or ethical?”

“Appropriate,” “right” and “ethical” are magic words. Other media can make the claim that they deal with those concepts, too – and they do – but in those media, the words belong to authors while in games, those words can and should belong to players.

Wrap your mind around all this, and we’re on our way to realizing the potential of games as a unique narrative form. Clearly, we owe something to earlier narrative models, but we can and must build on their teachings, maybe even leave those teachings behind to create something more collaborative, more moving and more compelling than any other medium can be.

Embracing choice means we’re halfway there. What do you say we go the rest of the way?

上一篇:万字长文,关于游戏在用户选择层面设定的考量分析,下篇

下一篇:关于日趋饱和的手机游戏市场

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号