万字长文,关于游戏交互理念与用户驱动方面的关联陈述,中篇

篇目1,社交游戏中的社交性分析

作者:Matt Ricchetti

谈到在线社交游戏,我们通常会立即想到两类内容:休闲社交游戏和硬核MMO游戏。虽然传统游戏设计师不满休闲游戏,称其依靠条件反射作用促使我们进行强制性操作,但这些游戏在Facebook和手机平台极度风靡。MMO游戏虽然备受追捧,但其已顺利运作许多年,获得非常忠实的粉丝群体。促使两类游戏获得成功的一个共同因素在于他们的独特社交机制,这可以总结为如下内容:

休闲社交游戏:

* 邀请“邻居”,赠送礼物,拜访好友的体验空间

* 非对称松散关系的异步体验模式

硬核MMO游戏:

* 形成党派及加入公会,同公会成员聊天,协调即时团体战斗

* 属于着眼于能够促成密切联系的对称关系的的同步玩法

作为Kabam硬核策略MMO游戏设计师/制作人及Zynga休闲社交游戏前任设计师/制作人,我非常熟悉这两类社交机制。我发现二者都能够带来富有粘性的玩法体验,表现都不相上下。

事实上,免费(F2P)、在线和多人体验在整个游戏市场中占较大份额,如今有越来越多的作品巧妙地将休闲和硬核题材的社交机制结合起来。《英雄联盟》就是很好的例子:Riot的返回DotA通过结合MMORPG PvP战斗、RTS决斗及更具休闲性的F2P游戏社交机制创造全新题材,多人在线战斗空间(MOB),从中获得丰厚收益。

Lobby screen in League of Legends from gamasutra.com

“社交”元素的发展大多受到F2P商业模式的推动。传统零售游戏只涉及一个用户决策:购买或不购买。而F2P游戏则需要玩家和开发者持续进行互动。由于准入门槛很低,玩家对于F2P游戏的忠诚度不是很高。这意味着开发者和发行商需要尽自己所能让玩家保有较高粘性,定期访问游戏。这可以通过核心玩法和高效创收机制实现;离开你已投入大量时间和金钱的游戏的机会成本相当高。

但“众包”粘性和留存率Vs.吸引眼球的社交功能依然是促使游戏既富有粘性又趣味横生的有效方式之一。单人游戏是种游戏,社交游戏则是包含各种有趣人际关系的社区:竞争、合作、同伴压力、叛乱、嫉妒及同情等更多因素。在电脑上体验《Scrabble》和《Words with Friends》所存在的差异体现在消磨时间和流行文化现象之别。

所以就今天的F2P在线社交游戏来说,“社交性”关乎用户体验和商业模式(游戏邦注:二者不可分离)。游戏设计师得判断哪种社交机制适合其作品的目标市场、玩法和商业模式。这些机制是在休闲Facebook游戏,还是硬核MMO游戏中出现无关紧要。

本文将基于3种一般探索方法分析用户互动,而不是通过有限二元透视方式。此方法的优点在于,这些探索方法能够运用至任何在线多人游戏中。在从特定游戏设计内容中释放出后,他们的功能价值变得更加突出。开发者因此得以选择最适合游戏设计的互动方式。

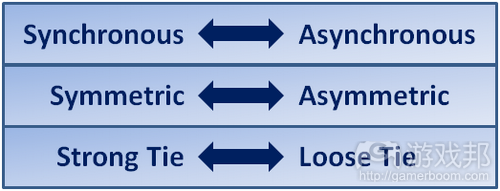

归类社交机制的3种探索方式

有关3种我们即将探讨的社交机制,一种是社交互动的时机,两种涉及社交关系类型。总的来说,这些机制概括多数在线游戏的社交互动内容:

* 同步Vs.异步用户互动:互动是即时同步发生,还是像回合游戏那样呈现于不同时间段?

* 对称Vs.非对称关系模式:形成关系是需要双方的输入内容,还是能够由单方构成?

* 紧密关系Vs.松散关系的发展:关系是会变得深刻而持久,还是浅显而短暂?

Three heuristics for social game features from gamasutra.com

下面我们将依次分析这些探索方法。

同步vs.异步

同步玩法的理念非常直观——玩家即时而不是依次进行互动。同步社交互动的例子包括文本聊天、视频聊天、用户vs.用户(PvP)战斗(游戏邦注:PvP属于一种社交互动方式)。同步玩法的覆盖范围从两位用户的正面交锋(例如耳语和决斗)到庞大团队交互活动(例如,大厅团体和突袭)。

下面就来具体谈谈聊天功能,因为这是提高休闲和MMO游戏用户粘性和留存率的强大同步工具。

* 新玩家会通过聊天功能结交朋友及询问基本问题。

* 经验丰富的玩家可以通过聊天功能炫耀自己的游戏成就,获得真正的友谊(游戏邦注:同时又通过各种活动消磨时间)。

* 硬核玩家通过聊天功能协调复杂团队体验(例如公会/联盟)及管理紧张局势和竞争关系。

无论这是用于经营《旧共和国》的主要公会,还是协助完成有关Pogo.com的徽章书籍,聊天都存在相似效果:提高用户粘性及长期留存率。如游戏存在活跃的支撑社区,玩家就会更频繁返回游戏,比较不会转而选择其他作品。在Kabam,我们发现这点弥足珍贵,因为我们尝试将更多硬核元素带入Facebook和网页游戏。

异步互动

“异步游戏”首先容易让人联想到较为缓慢或不那么稳固的内容,但异步玩法也可以和同步玩法一样富有粘性——不妨想想和好友玩国际象棋,或是基于邮件的外交手腕。异步玩法各式各样,常见类型如下:

1. 基于回合模式的共享游戏:这类题材的例子包括《With Friends》系列,及我的最爱《卡卡颂》。它们在社交性方面表现突出,原因如下:

* 每个操作都是个迷你游戏

* 存在返回游戏,完成下个回合的社交压力

* 正面竞争的挑战

* 小规模玩法容易适应日程安排

* 玩家能够同时体验多种游戏

2. 基于回合挑战的游戏:从根本来说,这包含两个独立组合:我玩你的AI,你玩我的AI;基于总计分数判断赢家。一个典型例子就是Facebook平台的足球游戏《Bola》。他们的社交性体现在如下方面:

* 回馈挑战内容所存在的社交压力

* 正面竞争

* 相比共享回合模式,内容包含较少等待机制,因为各玩家能够独立完成整个游戏内容。

* 进攻和防御的各种策略极大丰富体验内容

3. 基于分数的挑战游戏:这是传统的“击败我的高分”模式,如《宝石迷阵闪电战》。这些游戏存在社交性,原因如下:

* 回馈挑战内容的社交压力(需要高人一筹的做法)

* 正面竞争,及遍布游戏的排行榜元素。

* 比回合模式的游戏融入更少等待因素,因为玩家会随时争取获得高分。

* 从另一方面来看,这些类型的游戏其实不那么具有社交性。

4. 开放世界的异步游戏:从很多方面看,这是标准的Facebook游戏模式,被运用至《FarmVille》之类的游戏中。这也是包含较深刻社交互动元素的新颖游戏所采用的游戏模式,如《Empires & Allies》和《Backyard Monsters》。他们具有社交性是因为:

* 模型支持各种游戏模式,包括单人和多人PvE及PvP。

* 能够在没有引入即时体验技术挑战的前提下朝MMO模式靠拢。

* 依然呈现休闲游戏的方便特点——能够在不同时间段进行较短的体验。

对称vs.非对称

能够促进我们把握此探索方法的最佳范例要数Facebook vs.Twitter社交关系的形成。

Facebook社交关系具有对称性:我请求变成你的好友,你需要给予同意回复,此关系方能形成:

* 核心社交单元:“好友”

* 优点:

—互相认可带来信任感

—允许更深层次的共享

* 弊端:

—属于仅限于好友的现场互动

—好友关系需要管理工具(游戏邦注:有时相当复杂)

Twitter社交关系具有非对称性:我可以在无需对方回复的情况下“关注”任何人:

* 核心社交单元:“粉丝”

优点:

—允许广泛传播

—促进信息的快速传播

* 弊端

—核心社交单元的投入性较低

—不那么具有私人空间,更多是平淡无奇的内容,因为传播筛选设备不是很复杂。

在线对称社交互动的例子包括交友、邻居机制、馈赠礼物、私人聊天及基于团体的帮派、联盟及手动多人配对。非对称社交互动包括个人范围内的关注、消息发布、发微博及撰写博客,以及团体规模的斗阵任务、帮派及随机配对。

下面就来深入探讨在线游戏的对称和非对称关系模式。

对称互动

在线游戏对称关系的典型范例就是MMORPG帮派。在MMORPG中形成团体需要同时获得邀请者和受邀请者的同意,通常是邀请者想要控制和自己共同探险的对象。

虽然这意味着受邀请者有时会只收到很少的邀请(或很多被忽略的请求),但这使得邀请者能够在组建团队时区分优劣。这令团队成员建立更牢固的关系,在PvE中创造有形“敌我”心理,形成高效的类组合,促进玩家进行符合关卡的道具和信息交易。

虽然Facebook游戏不是以这类对称关系著称,但这些元素确实存在于许多平台游戏中。例如,广泛存在于《FarmVille》这类游戏中的邻居机制就是个对称社交关系。就连置身同款游戏,已是FB好友的玩家也需要互相建立“邻居”关系。这种额外的社交障碍造就持续性的“利益朋友”互动关系,其中玩家互相赠送更多礼物,互相解锁“社交关口”(游戏邦注:例如,“你需要将5位好友安置于此建筑中”,或者“你需要10个解锁门的密钥”)。

Friend ladder in Cityville from from gamasutra.com

非对称互动

Facebook游戏还存在许多非对称社交活动。和邻居机制不同,许多游戏允许玩家直接将自己的Facebook好友添加至体验空间中,无需征得好友的同意(例如《宝石迷阵闪电战》)。在我们Kabam的作品《Dragons of Atlantis》中,玩家可以选择任何一位Facebook好友充当军队的将军,即便他们没有频繁体验这款游戏。

这些类型的游戏比上述邻居机制更为浅显,但由于它们涉猎广泛,因此能够降低互动障碍,在玩家间建立密切关系。在《宝石迷阵闪电战》中,允许玩家查看好友的高分,从而产生追逐心理非常重要。游戏若未融入显眼的排行榜就无法实现此目标。在《Dragons of Atlantis》中,邀请非玩家好友充当将军的优点是,能够通过墙面公告以个性化方式提高游戏在潜在新玩家中的曝光度。

非对称关系也存在于MMO游戏中。典型例子就是《Warhammer Online》中的“斗阵任务”功能。这类团体PvE旨在促使游戏自动基于斗阵任务点附近的所有玩家建立临时帮派,从而避开对称团体结构的常规障碍。例如,若某地已被恶龙统治,附近人员就会自动加入斗阵任务,将龙杀死。玩家能够轻松感受到团队体验模式,然后在随后的过程中按照自己的方式进行操作。低社交障碍让玩家能够进行更频繁的合作,虽然这意味着游戏需要放弃常规团队元素,如聊天和道具买卖。

紧密联系vs.松散联系

对称vs.非对称描述关系形成方式,但未呈现其发展模式。例如,居于在线游戏约会地点的“Long-term Relationships Only”区域遇见的玩家比在“Casual Encounters”区域遇见的玩家结婚率更高——但情况并不总是如此。最终关系还是取决于初次见面后所发生的情况。密切联系vs.松散联系是衡量社交关系发展情况的简单探索方式,其焦点在于互动深度。

密切关系的覆盖范围从1:1模式(例如双人合作体验模式和RPG玩家)到团队团队(公会、联盟和社团)。松散游戏关系同样也是小到1:1模式(如游戏邻居),大到团队规模(帮派、级别和比赛模式)。

帮派vs.公会

紧密联系通常具有对称性——这有其道理,对称模式的必要条件就清楚表明其中关系瞄准更深层次的共享。相反,松散关系则属于非对称性,虽然这并不是绝对情况。

公会vs.帮派是MMORPG紧密关系vs.松散关系的典型例子。玩家通常会在游戏开始选择自己的帮派(例如,非对称性)。帮派关系在决定玩家体验的核心要素方面扮演重要角色,例如玩家将会接触到的类别,他将在何处进行自己的探险活动,以及他将遇到什么关卡。就社交性方面来看,它就像是遍布各处的胶质,将“我们”同“他们”分隔开来,或是将“好伙伴”和“坏伙伴”区分开来。所以即便玩家遇见某位和自己毫无共同之处的伙伴,共同帮派也会给他们的关系形成奠定基础。

公会则截然不同,它们通常不会影响玩家的核心体验,所以从根本角度看,它们也不是初期游戏体验的关键要素。但只要玩家参与至优秀公会,它所带来的直接社交益处就会直接转变成游戏变化。公会是玩家买卖道具、学习最佳策略及技巧,以及获得法术及其他益处,当然还有结交朋友的地点。我们可以谈论众多有关《Chronicles of Merlin》联盟(例如,公会)成员的个人信息,尽管我们并不知道他们的名字或者从未见过他们。我们甚至还有自己的Facebook页面,会在游戏之外同其他玩家进行互动。

帮派vs.邻居

松散关系并不总是属于非对称模式。上面提到的Facebook邻居其实就是对称松散关系的典型例子。邻居关系旨在共享礼物和少量虚拟货币,而不是为了进行广泛聊天,制定战略或进行合作。这里对称关系只是为了更好地充分发挥Facebook平台的传播性。要求玩家确定邻居关系能够促使他们互相发送请求,这是值得鼓励的游戏初期重要操作。

类别细分化

松散关系并不总是等同于较低游戏影响。就如上面所提到的,帮派在塑造玩家体验方面扮演重要角色。另一松散关系的典型范例是类别细分化。类别细分化显然具有社交性;它促使团队战斗存在相互依赖性,定义MMO经典的受攻击者/治愈者/DPS三元组。

但它并不是紧密联系。你我都是魔术师并不代表着我们将变成可靠的朋友。相反,和帮派一样,类别细分化是定义玩法结果的宽泛恒定元素。有趣的是,由于类别细分化具有非对称性,你最终也许会得到过多的同类玩家。虽然多数游戏都具有平衡性,但从在全球范围内来看就不是如此,我们多数人体验的依然是糟糕的PvP战斗,其中一方由于缺乏“___”或拥有过多“___”而重复进行摧毁操作(游戏邦注:你可以在上面的横线中填入受攻击者/治愈者/DPS内容)。

案例学习:《亚瑟王国》

综述

为更好说明如何通过这些探索方法把握社交机制内容,我将把这些方法具体运用至一款我再熟悉不过的游戏——《亚瑟王国》。

我们刚着手《亚瑟王国》时雄心勃勃:制作一款Facebook MMO游戏。我们意图将硬核策略玩法同Facebook的内置社交/传播渠道及深层次的免费模式用户粘性和创收模式结合起来。

凭借技能、运气和毅力,我们最终实现自己的目标,制作出一款相当成功的Facebook游戏。《亚瑟王国》在2年后的表现依然相当突出,如今游戏依然是各个平台的热门策略游戏之一,目前有49万的MAU,所以我们的理念完全正确—–尤其是在社交性方面。

下面就来看看游戏的表现突出之处,及我们能够在MMO和Facebook社交元素方面做出什么调整。

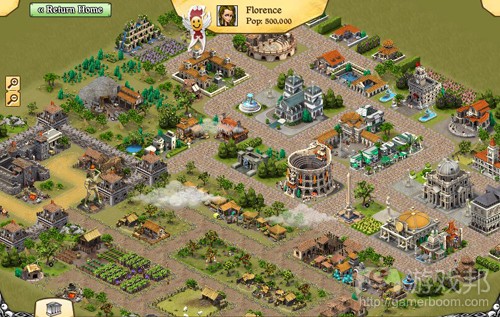

Facebook游戏《亚瑟王国》

《亚瑟王国》在Facebook的表现相当突出,游戏中玩家可以扮演单人模式的任务推动型城市建设者。适合Facebook的主要社交机制包括异步战斗、邀请/请求之类的好友梯子、资源赠予及针对建造帮助等活动的病毒式传播内容。

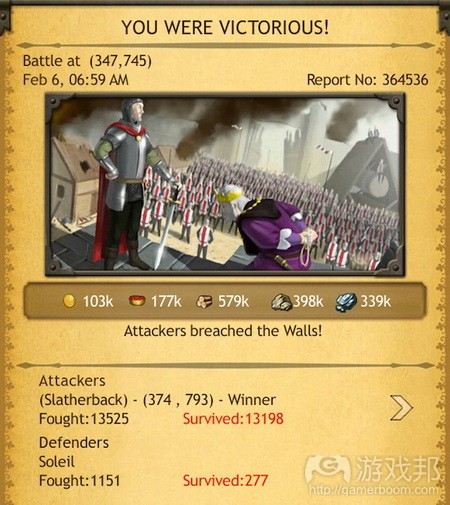

战斗:《亚瑟王国》中的战斗属于异步模式:攻击者针可以对任何玩家发动战斗(游戏邦注:即便是离线玩家),他的军队会朝地图上的目标迈进,随后战斗情况和结果就会在操作完成后以公告形式发送至玩家的收件箱。此简单定时机制既支持小规模的Facebook体验模式,又接受有趣的PvP模式。

《亚瑟王国》也属于非对称模式,其中玩家可以锁定任何目标。这款游戏的空间是开放的战地,并没有像某些PvP机制那样融入大厅或配对元素。“始终在线”功能也受到极大削弱,因为初始玩家能够避开进攻,玩家可以将自己的军队隐藏至“避难所”,防止自己在离线时失去这些人员。

Battle report screen in KoC from from gamasutra.com

邀请/Request机制(异步,非对称):和所有Facebook游戏一样,玩家爱可以向好友发出邀请,创建好友阶梯。你可以邀请好友充当领导军队的骑士,你可以向好友赠送资源礼物和军队。玩家可以随时和离线好友互动(异步),但好友需接收邀请和请求(对称)。

社交消息公告(异步,非对称性):《亚瑟王国》的消息公告和其他游戏类似,但更着重物质元素,即游戏奖励(游戏邦注:主要通过炫耀)。例如,玩家可以通过分享Merlin的魔法盒符号赢得免费虚拟商品或发布病毒式传播消息“Build with Help”请求,在此玩家的Facebook好友只要进行点击,玩家就能够缩短建筑创建时间、调研耗费时间或军队训练时间。

补充内容

可取之处:

* 通过添加异步战斗内容进一步发展Facebook城建题材

* 植入能够提高病毒式传播/粘性的Facebook核心渠道

提升空间:

* Facebook渠道的植入方式不像其他游戏那么深入

* 没有“好友拜访”或满足虚荣心的社交状态

* 好友邀请和馈赠没有同游戏进程或游戏资源绑定

* 消息公告只被运用至若干功能中,旨在限制病毒式传播。

除了基于核心的Facebook整合机制,《亚瑟王国》的创造性还体现在它就像是一款真正的MMO:包括社交和战斗功能中的突发性行为都带给玩家深刻的沉浸式体验。游戏的战斗系统突出了开放世界的PvP模式,比赛以及排行榜,正如以玩家为主导的MMO游戏那样。而其中所包含的传统MMO社交功能还有:联盟,聊天,发送信息以及交易。

MMO战斗(同步,紧密联系):因为《亚瑟王国》的战斗系统是基于开放世界群组的PvP,所以能够驱动同步且紧密联系的社交互动行为。尽管个体攻击都是异步的,但是如果玩家能够结成联盟,便能即时进行规划,谋略并发动一系列攻击。

游戏中定期举办比赛并让玩家能够从中获得奖励并进入全新世界,如此不仅能够创造更多不同的PvP竞争模式,同时也能够鼓励玩家反复回到游戏中进行挑战。而个体和联盟排行榜作为游戏战斗的测量杖,有利于进一步提高玩家在游戏中的社会地位感并增强其竞争意识。

联盟(同步,紧密联系):游戏的联盟结构和社交工具能够促成玩家间的紧密联系。

游戏中的“联盟外交”功能让游戏联盟能够将其它联盟当成朋友,敌人或中立者,并创造一种对称(即联盟双方必须遵守共同的外交标准),异步(联盟双方不需要同时在线才能进行外交)且紧密联系(永无止尽地争夺地位)的联盟社交游戏元素。

同一个联盟中所存在的不同社会地位和力量差距也产生了一种紧密的联系。即每个联盟中都有一些精英玩家扮演着领导者的角色,如“Chancellors”和“Vice Chancellors”,并由他们决定谁有资格加入该联盟。

对于玩家来说,被一个联盟拒绝就像是被一所名校或者一份好工作拒绝一样:这将激励他们更加奋进,并努力组建一个更强大的敌对联盟而让之前的联盟后悔自己的决定。

而联盟与其它同步且紧密联系的社交工具(游戏邦注:如聊天,发送信息和战斗报告)的区别就在于前者还允许联盟之间进行相互交流,制定策略并即时传递信息。比如一个联盟的玩家与其它联盟玩家的相互描述可能完全不同于他们之间的外部交流。

聊天(同步):《亚瑟王国》中的聊天功能是一种重要的同步社交功能,能够让游戏世界更加生动且更具有实时性。三种不同层次的聊天功能让玩家能够通过三种不同的方法进行交流。联盟聊天和私聊渠道(对称,紧密联系)让玩家能够在等待建造过程中培养彼此间的关系。全球化聊天渠道(紧密或薄弱的联系)允许新手提出各种问题,并且能够鼓励不同联盟之间进行言语上的挑衅。

发送信息和交易(异步):发送信息(对称,紧密联系)是用于传达机构信息和后勤情报:联盟规则,公告,战斗计划,敌人信息等。资源交易(对称,薄弱的联系)属于非战斗的游戏层面,是关于玩家间买卖商品的社交互动行为。

可借鉴之处

《亚瑟王国》为Facebook社交游戏注入了同步且紧密联系的MMO游戏元素,在此平台上创造了一种全新的游戏体验。

可取之处:

*基于Facebook游戏的分层同步MMO PvP战斗模式

*将紧密的联盟关系作为游戏基础

*以社交工具支持着战斗系统,从而造成对同步/异步以及对称/不对称关系的影响

提升空间:

*通过添加额外的战略/战术而加深战斗系统(如PvP模式外还有PvE模式)

*进一步延伸联盟的社会结构(例如,除了工具和分享资源外还支持更广泛的游戏形式)

*提供额外的交流工具(例如,对于关键事件/交互的离线通知,联盟军官及其下属的额外交流渠道等)

结论

当在线游戏变得越来越单调时,我们有必要进行更多社交创新。而当我们在Facebook上创建了早期硬核MMO《亚瑟王国》时,我们更加清楚地意识到这款游戏与之前游戏的区别。从那以后,Facebook越来越倾向于MMO,并且出现了越来越多PvP游戏。甚至一些休闲游戏开发巨头如Digital Chocolate和Zynga也加入了这一行列,分别推出了《Army Attack》和《Empires & Allies》。

《亚瑟王国》场景(from gamasutra)

与此同时,一些非Facebook游戏场景也变得越来越“休闲”(或者更加具有社交性)。现在的玩家希望所有在线游戏能够同时提供完整的多人游戏功能以及交互式功能。特别是在近来的AAA级MMO社交游戏机制中表现得更加明显。

举些例子来说,《魔兽世界》在最近更新内容中将“灾难”场景添加到公会袭击功能中,而让玩家更容易接近PvE模式。《星球大战:旧共和国》这款MMO游戏让玩家既能够单独进行探索也能够加入混合类别的派系中进行冒险。

不同类别的故事探索是《旧共和国》与早前游戏的最大不同,并且也体现出了游戏对于社交易用性的明显妥协。

最后,免费游戏模式也开始影响游戏元素。大多数早前的订阅MMO,如《龙与地下城OL》,《科南时代》,《指环王OL》也都开始向F2P模式转移。而一些非MMO的硬核游戏,如《军团要塞2》也开始使用F2P模式。世嘉不久前也公开了他们针对于PlayStation Vita平台的第一款真正F2P游戏《Samurai & Dragons》,这款游戏取材于畅销iOS游戏《王国征服》。

如此变化也意味着我们的游戏更难凸显于众多竞争对手中,但是也正是如此,独创性变得越来越重要了。

利用这些探索法

我们所描写的三大探索法并非适用于所有社交游戏设计,但是它们却具有很强的教育性。你可以使用这些方法去评估现有的游戏或设计新游戏。

对于现有的游戏,你可以基于这些探索法分解你的社交机制,判断这些同步/异步,同步/对称以及紧密联系/薄弱联系功能的使用是否合理。并自问所使用的方法是否真的适合玩家,游戏玩法以及目标平台。例如,年长的玩家可能不喜欢同步玩法,而年轻玩家则钟情于这种玩法;“充满紧张感”的街机游戏不适合紧密联系;手机游戏就必须具有足够的社交性等等。并问自己:你会做出何种改变,为什么?

特别是当你从头开始创造一款社交游戏时,更能深刻体会到这些探索法的价值性。如果你能够合理使用这些方法,便能够在原本的二进制休闲/硬核游戏设计方法中添加新颖的多层次社交互动元素。比起将一些新的社交功能移植到现有的游戏,在设计游戏之初就创建一个强大的社交层面,并将其融入游戏玩法中的这种做法更加简单。

当你的项目运营和用户目标转移到游戏功能时,你需要更加关注于那些特殊玩家所频繁接触到的社交机制。尽管你精心设计的社交功能不一定会对用户或者项目产生明显影响,但是它们却能够深刻影响游戏界面以及核心游戏玩法。

同时你还需要记得,混合型社交机制更有效。如果《亚瑟王国》只体现出Facebook元素或MMO的社交机制,它便不可能取得如此巨大的成功。不管是对于开发者还是玩家,Facebook的病毒式用户获取渠道和早期用户留存渠道,加上MMO更深层次用户粘性和盈利性的社交互动才是最完美的组合。

最后需要牢记,这些探索法只是经验法则,并非绝对真理。你需要好好学习这些法则并以此造福游戏和玩家!

篇目2,阐述MMO可向社交游戏借鉴的设计经验

作者:Eliot Lefebvre

几个月前我曾经说过,社交游戏并不会破坏MMO。我想除了Richard Garriott和Zynga的股东,这对于任何人来说都会是一个好消息。但是如果我们以此而忽视社交游戏,这便是一个严重的错误。

在有些内容上,社交游戏的表现比MMO好得多。但是我并不是在暗示社交游戏比MMO更加出色,而是想传达社交游戏更擅于处理社交元素,而MMO则在选择提示上更加突出。

我们都很反感玩家在Facebook上玩社交游戏时只是在重复一系列可疑的成就。但从整体来看,游戏中仍存在许多有帮助的元素。

.jpg)

soapbox-social-epl(from massively.joystiq)

没有限制地提供帮助

Lady小姐和我都很喜欢玩电子游戏,这也是我们为何能够一下子变成好友的主要原因。不幸的是我们对于MMORPG的态度并不相同。我倾向于在游戏发行时便踊跃尝试,或在阅读了《Choose My Adventure》系列文章后做出选择。而她总是犹豫不决,直到我跟她说一款游戏是否值得玩。而问题在于,当她最后进入游戏中时,因为我的级别是基于科学计数法进行衡量,所以她并不能给我带来任何帮助,而我也只能通过杀死其身边的敌人去帮助她。

但是如果我们玩的是《FarmVille》,我们便能够为彼此的庄稼浇水,而不管游戏级别。

大多数社交游戏都带有一些变量。就像《FarmVille》还让玩家能够送礼物给别人,并且游戏会奖励玩家的这种行为。《Dragon Age Legends》让玩家能够将好友的角色招到自己一方,也就是当玩家在游戏时能够面对一些较轻松的内容。大多数社交游戏都提供了一些小窍门让玩家双方都能够获取利益。

MMO的设计师已经意识到,让玩家加入好友所推荐的一款游戏但却发现对方的级别已经远远超越于自己并不是一种有趣的体验,而大多数游戏也尝试着添加各种系统去解决这一问题。但麻烦的是,大多数解决系统仍是关于级别的起起落落。并不存在哪种任务能够让两名角色等价地帮助对方,而无需衡量相互的游戏级别。

在许多MMO设计中,玩家要么就是和其他玩家一起经历整个地下城,要么便是分开进行探索,但是在大多数社交游戏中,玩家能够抽出5分钟时间去帮助别人,然后再回到自己想要进行的内容中。

《激战2》在这方面便做得很好。游戏并不会推动着所有玩家去完成一个共同的目标,而会帮助玩家双方进行更长时间的探索。这是玩家帮助别人的快速机会,并且所有玩家都能够从中获利。

互利的商业关系

你的团队中之所以需要治疗师是因为你需要他。当然了,你也喜欢他。这是一个很优秀的人,你能够与他谈论游戏,他也会在早期给你一些不错的建议,你为他在自己的领域中提供了一个很不错的工作。你们当然是彼此的朋友。但是你们的碰面是因为你需要获得治疗,而他刚好能够满足这一需求。他在游戏中的功能便是维持你的生命。

这种关系并不丢人。当我身处于一个团体中时,我便在执行一个角色,而不是传达有关设计风格的任何观点。像这样的游戏关系是基于一定的双方利益,即使最终你们是先变成了好友,然后才是MMO中的伙伴。

但是事实上却没人愿意承认这一点。根据多方面来源的支持,玩家在MMO中的群组总是先由好友构成,其次才是维系同盟关系(游戏邦注:或者这种同盟关系永远都不会出现)。尽管游戏总是会鼓励你去与那些能够提供可行利益的人一起游戏,但却只有少量游戏能够基于共享的社交利益而提供明确的内容。

而在社交游戏中就不会出现这种幻象。玩家需要获得更多好友并与他们一起游戏。通过分发礼物而获得游戏奖励。主动帮助其他人,因为这也能为自己带来长期的帮助。

玩家们之所以不在意这种“蒙骗”是因为在此之前他们已经变成了自己的好友。另外一个原因是游戏让玩家的任何行动变得更加透明。你提供给别人帮助,并希望他们也能给予自己帮助,这并不是什么坏事。反正所有人都能得到自己想要的。

这些要点便组合成了一些有用的社交互动理念,而无需任何专门的群组内容。想象当你给予别人一块软牛皮后你自己也能得到一块,或者当你为其他玩家提供一定的服务便能获得经验值的提高。想象当你访问游戏内部好友的性能后便能够清除周边的动物,从而获得更多经验值并提高彼此双方的游戏属性。这便是无需花费大把时间,无需要求正式群组聚集在一起或无需假装自己是为了别人而提供帮助等而进行互动,并相互获利。

共享有趣的内容

社交游戏遵循着病毒式的发展途径;它们会要求玩家去传播自己在游戏中所进行的各种任务,因为让更多人认识游戏是社交游戏开发商赚钱的主要方式。所以每款游戏的更新以及玩家在游戏中所获得的成就等都会出现在他们的状态页面上。

这种做法的作用便是让玩家的好友能够感受到游戏乐趣。这也是我认为MMO在设计趋势和原理等方面所具有的缺陷。最后,我认为在玩MMORPG时最棒之处在于玩家能够基于同一个虚拟平面与其他玩家共同游戏,即使他们并非同时面对着游戏(生理上)。

过去几年里,游戏领域的准入障碍大大降低了,如果玩家想要玩《星球大战:旧共和国》或《冠军在线》或《无尽的任务》,他便可以轻松地进入游戏中而非前往商店购买游戏。但仍然存在着一种执念,即必须设定一些有趣的内容去阻碍你出色地完成游戏中的某些任务。而通过努力,你便能够感受到其中的乐趣。

我们还需要解答一些问题,即为何不让社交游戏发起带头作用?为何不邀请好友并立即提供给他一些有趣的内容,然后让他不断提升这些内容的层面,帮助你更好地享受游戏?为什么不告诉他有趣的事物作为奖励,而是强迫他必须不断刷任务去赶上你的游戏进度?

MMORPG最大的弱点便是游戏总是会强迫玩家在经历许多任务后才能真正感受到乐趣。而社交游戏则是能够直接呈现出这些乐趣。这便是MMO设计师需要向社交游戏学习的内容。

篇目3,社交游戏的真实交互效能分析

游戏邦注:本文原作者是资深游戏设计师Greg Costikyan,他称当前不少游戏都被冠以“社交游戏”之名,但它们多数缺乏“社交”之实,并在文中总结了成功社交游戏应具备的要素:团队、外交、商贸、资源竞争、等级系统、表现。

三年前,我的朋友Eric Goldberg问我有没有兴趣为他供职的一个小网络公司开发一款“社交游戏”。

社交游戏?听起来有点意思。我非常喜欢的LARP(游戏邦注:它是live action role-playing game 的简写,指玩家自己扮演游戏角色,在现实场景中玩游戏)就算得上是一种社交游戏(LARP游戏很能促进玩家间的互动,有点像模拟城市游戏,非常适合在纽约一年一度的街头游戏节Come Out & Play上玩)。

社交游戏应该算得上是在线论坛和游戏的结合体,一些还兼有战争游戏的细节特征。

如果能把社交元素组合成一款游戏,那应该会让人颇有成就感吧。真的有人会请我做这样的游戏?

不会吧?我有些怀疑地问Eric,他所谓的“社交游戏”是指什么?

听完一堆废话,我终于明白他的意思。我直奔主题:“呃,我明白你的意思了。是要做一个在社交网络上面玩的游戏。这就是真正的社交游戏了?”

电话那头的人也许对我的问题有些吃惊吧。我要不要这份工作呢?

当然。我要接这个活。

在我13岁时,我就是一个狂热的桌面战争游戏的粉丝了。那时候的SPI和Avalon Hill还是战争游戏领域的佼佼者。我甚至花时间研究战争游戏分类表,那种表的分类项目有拿破仑战争和二战等等。我要找出一种自己想要的游戏风格,然后深入学习,并最终成为专家级人物。最后我决定专攻的游戏模式是:多人游戏。

从数字上看,只要不是单人游戏的就是多人游戏;就战争游戏而言,因为是关于双方对抗,所以多人游戏就意味着“两个以上玩家参与的游戏”。《Diplomacy 》和《Kingmaker》就属于我所选择的“多人游戏”。多人游戏比双人战争游戏更吸引我,是因为它的互动程度的复杂度比单纯的双人游戏更灵活多变。谈判、结盟、贸易和了解变得很重要——这类游戏要关注的不只是系统和操作技术。

我花了很多时间研究谈判、结盟、暗算,还学习如何与他人打交道。

当我14岁时,《龙与地下城》问世了。这款多人合作桌面游戏开启的奇幻世界,就像我喜欢的小说中的世界那样不可思议。我久久地沉浸在游戏世界中,学习如何合作、劝导、在夸张的场景中“即兴表演”。我和其他玩家一起书写属于我们自己的游戏人生。

多亏了《龙与地下城》这款游戏,我终于没有堕落为一个只知勤学苦读却沮丧压抑的木鱼脑袋,而是成长为落落大方的魅力青年。是它教我成为一个社会人——当然不是秉承这个游戏的制作人Gygax 和 Arneson的旨意,却是出于游戏的本质。

多年以来,数字游戏对我而言就是百无一用,一部分是因为这类游戏缺乏智力和讲述的严肃性,但更多地是出于其固有的孤立性。然而,正是《M.U.L.E.》这款游戏,让我意识到数字游戏也可以非常擅长“社交”。

unsocial_mule wide(from gamasutra.com)

我很早就进入在线游戏的设计领域,那时网络还没进入寻常百姓家呢。我也很早就开始通过商业在线服务网站玩游戏,因为在线游戏能最大地弥补数字游戏的不足——固有的单人游戏本质。

近年来,我又开始对LARP(实景角色扮演游戏)、独立RPG和剧情游戏着迷了,因为这些游戏一直以社交、即兴和虚拟角色作为游戏的焦点。

社交游戏的正确定义是非常重要的。我认为,社交游戏的重点就在于“社交化”,所以做好这类游戏的方法就是“社交化”。

很遗憾的是,所谓的“社交游戏”并没有那么擅长“社交”。

人类的最根本矛盾之一是,人类是独立个体和社交动物的结合体。在社交中,我们每个人都失去了自我的思想,只是靠有限的表情和语言互相交流。在个体中,我们往往以牺牲他人为代价来满足自己的需要和渴望——我们是自私自利的个体,客观上我们是利己主义者。

然而,没有父母的养育我们无法成长;出于寻找朋友和伴侣的需要,我们合作、交流,共同建造了文明的大厦;我们享受与朋友相伴时的快乐。

我们既是自由的,也作为社会的一员受制于社会;我们是消极的旁观者和积极的参与者;我们是自由的思想者和支持者;我们是有力的竞争者和合作者。

我们崇尚个人自由,也倡导集体主义。我们在世界的大舞台中独唱,也能在合唱队里放歌。即使是极其重视个人自由的美国人,也知道为了完成所有任务,我们每个人都必须同心协力。

尽管我们生、死、孤独都是自己的事,我们的思想也禁锢在自己的躯壳里,我们仍然不能摆脱社会人这个身份。

我们的快乐是他人的馈赠——伴侣和孩子、朋友和其他人的赞赏和认可。就算是在虚拟的游戏世界,我们最快乐最感动的时光也是因为他人的存在而存在的。

曾几何时,在《魔兽世界》里,你和公会的成员一起完成了突袭任务;在RPG的搞笑的游戏过程中,我们一起放声大笑;在jeepform(游戏邦注:一些北欧的RPG玩家和制作人自创的一类游戏风格)或者剧情游戏中,我们因为与他人意外的合作而倍感激动;在欧式游戏中,我们互相开着玩笑;甚至是在最常见的卡片游戏中,和朋友在一起闲谈和研究自己得到的卡片——这些都是值得珍视的经历。

甚至是在单机游戏或者游戏机游戏中,你能回忆起的最感人肺腑的经历,不是辉煌的胜利和熟练的操作,而是体会到他人的心意的瞬间、明白游戏意图的刹那、理解游戏言外之意的时刻。

灵光一现,你最终明白:沉浸于他人的创意之作的感觉;参与文明对话的感觉——这些感觉的重要性至少不亚于游戏中的得分。在这些情境中,玩家并不是直接感觉到游戏的社交性特征,毕竟只是一个人在经历这些体验(但这些经历又不断沟通玩家与制作人)。

如果你是世界上的最后一个幸存者,你会玩游戏吗?如果会,除了让你为失落的文明感到悲伤,游戏还能做什么?(已经不存在社交性了)

一旦失去,方显珍贵。无论是什么形式的艺术,社交性的存在才让它们成为引人注目的艺术。在社交设置上出彩的游戏通常也是所有游戏中最强势的存在。

“社交游戏”就是致力于挖掘玩家之间的社交纽带,才有了无限的潜能。任何形式的艺术都不例外。

然而,很不幸,真正称得上是“社交游戏”的,寥寥无几。

第一个在商业上获得成功的“社交游戏”是SNRPG(社交网络角色扮演类游戏),如以黑手党为主题的《Mafia wars》和其他吸血鬼题材的游戏。与常规的数字RPG游戏类似,玩家在游戏中操作一个角色完成任务,完成任务后可以升级。这类游戏的任务难度已经非常之小了——只要点击一下鼠标就能完成了,升级就可以开启新任务,同时得到一定的“精力”(这是升级的主要制约因素,因为玩家在一个时间段内只能完成一定量的任务,所以“精力”的填满速度比较慢)。

unsocial_mafia wars(from gamasutra.com)

除了完成任务和升级,玩家在SNRPG类游戏里还可以攻击其他玩家。在进攻时,玩家的状态(可以通过等级提升)可以附加到装备上。在战斗中,胜利的一方得到经验和金钱,失败方损失金钱和命值。

对游戏的扩散性特别重要的一点是——你可能邀请朋友加入自己的部落(集团、帮派或者家族之类的)。在战斗中,朋友的价值可以提升你的自身价值,即你所在团队的成员越多,你的势力越大,升级越快,越不容易受到别人攻击。

事实上,SNRPG在本质上完全是孤立的(除了进攻其他玩家和招纳团队成员以外)。所谓“部落”,徒有虚名罢了;每个玩家的“部民”列表和玩家本身没有半点关系。

如果我加入你的“部落”,这并不等同于我与你的其他“部民”就有所交集;我可以同时加入无数个“部落”。与这些“部落”的唯一关联就是增加了团队的战斗力(当然也增加了我自己的战斗力)。“部落”只是图有虚名罢了——没有组织、没有交流和计划机制、没有共同资产。这种“部落”确实“原始”得只剩下一个列表了,和MMO的公会是没法比的。

你在这种游戏中可以发送信息给你的“部民”,有时候却会引发意想不到的“笑”果——聊天语句完全是牛头不对马嘴,因为你的“部民”正在和他的一个不属于你的“部落“的“部民”聊天,而你只能看到一边的对话。

这种“部落”存在的唯一意义就是招揽“部民”的玩家有一个列表排列朋友,所以玩家可以通过交友扩充“部落”人丁。现在我自己就有过三百个社交网络的“朋友”,不过我不认识他们,事实上也没有兴趣认识他们。 我结交这些“朋友”只是为了在SNRPG的战斗中更有战斗力罢了。

你大概可以说,其实这些SNRPG在本质上是反社交的,因为玩家之间真正的互动只有一个——攻击对方。

现在,大多社交网络游戏本质上是轻模拟生活/经营风格的游戏。你可以控制一个地图,在上面建造建筑、摆放装饰、种植庄稼等等。通过这些活动,你可以积累财富(过一阵子就点击一下那些物品,回答对话框)。

有时候,但不总是,你可以操纵一个角色,点击一下物品,让角色完成你的指定任务。时间久了,自然就升级了——你可以使用更多特定物品,玩到更多游戏内容。你通常要积累徽章、收集物品和达成其他任务。

换句话说,这种游戏的核心就是其固有的孤立本质——你以一己之力发家致富、建造城市;而其他人也在自己的小世界里忙得不亦乐乎。

然而,模拟社交经营游戏里却实存在一些玩家互动的把戏。其中一个系统名为“赠礼”——鼓励玩家送免费礼物给其他玩家,收礼的玩家不需要付出任何代价就可以得到可观的好处。

通常在游戏中,玩家可能要集齐一些关键物品,然而这些关键物品本身的获得又要靠收集其他只能通过玩家的赠礼得到的物品,这样,玩家就不得不请求其他玩家赠礼了。当然,如果玩家的朋友不多,或者玩家本身没什么耐心,那么花点真钱也是能解决问题的。

为了通过社交网络社区的通信渠道滥发游戏信息,玩家当然会夸耀自己的成就,这样就能吸引新玩家加入游戏(模拟社交经营游戏仍然鼓动这种方式,不过Facebook对这类信息进行了限制,以免非游戏玩家为其所扰)。

玩家可以“游览”其他玩家的地图,也可以在朋友的地图上做点任务。这样,虽然各个地图实际上是独立的,玩家还是能感觉到其他玩家的存在。

如果你指望模拟社交经营游戏可以促进游戏内部交流,那你还是清醒一下吧——所有可能的交流活动或者玩家试图与他人接触的行动,只不过是为游戏开发者服务。各种交流活动的存在是为了三个目地:吸引新玩家(扩散性)、鼓励玩家回归游戏(留存率)、促进游戏交易(虚拟消费)。

玩家的互动活动对游戏的影响不大(如果有的话)、对游戏结果没有影响、没有或者事实上对玩家的参与也没有影响。

如果SNRPG其实是反社交的,模拟社交经营游戏其实是缺乏社交特征的,这些游戏的互动活动本质上是非社交的,因此,交友结仇和玩家间的互动没有关系,给玩家带来的关系感也很脆弱(如果有的话)。就像MMO中的单机游戏——你知道其他人的存在,但他们的存在和你没有太大关系。

社交游戏开发者的野心很大很清楚:利用社交关系图鼓励玩家的参与、逗留和消费。但据我所知,这些认识从来就不是为了建立玩家间的联系或者增加游戏的可玩性,只是为了钱——和游戏社交化没有任何关联!

社交网络具有的特性,使之事实上比大多在线游戏更适合发展社交特征。这些特性就是,系统中具有发送信息和聊天的功能,且不需要由开发者分别执行;但更重要的是,社交关系图让玩家与真正的朋友得以互动。

大多在线游戏都很难做到这两点。例如,MMO因为其分割式的游戏特征,是不可能让真正的朋友在一起玩的。例如,我知道你是《魔兽世界》的玩家,但我们两个是在不同的服务器上玩,如果我想和你一起玩,我就要换到你所在的服务器,从1级开始重练。

即使我和一大帮朋友决定在同一个服务器从头开始,我们还是面临着现实的困难:不同的游戏时间和不同的游戏强度。所以就算我们一起站在1级这道起跑线上,我们的级别还是会渐渐地拉开距离。因为MMO游戏的内容是靠等级把关,所以如果你是5级,我是20级,我们真的很难在一起玩——在我这个级别所在的地图,你只能被秒杀。

在社交网络上,发现你的朋友在玩什么游戏并不难,安装一个允许玩家一起玩的系统可能也不难——为一群朋友推迟游戏进程,或者设计出一个系统可以兼容不同等级的网友玩家。

即便允许快速带级,在线网站也还是不能达到要求——在Pogo网站或者Days of Wonder公司的网站上随便就能找到人一起玩,但毕竟是陌生人,怎么比得上和朋友一起玩来得有趣吧。而社交网络提供的信息和共享内容的功能,意味着执行一个允许和真正的朋友一起玩的游戏应该比其他在线网站容易得多。

总之,开发者知道怎么利用社交关系图吸金,却不懂得怎么设定一个真正的社交游戏过程。

“真正的社交”游戏设置是什么样的?这不是谜。以下内容虽不详尽,但至少给出了一些参考意见。

团队

在团体运动中,你必须与你的队友配合。如果你本身是一名优秀的运动员,那当然最好了。假如在篮球赛中,你不去搞清楚队友的位置,也不好好准备传球(或者从队友那接球),那么,你对队伍的贡献真的不太可观了。

运动是一种表情指向的交流,极少用到手势,配合得当的队伍往往更容易战胜那些配合不佳的队伍。

任何团队性活动都是这样的。在团体射击游戏,如《反恐精英》,队伍合作的重要性至少相当于FPS游戏的个人技术。在《魔兽世界》里,要战胜BOSS,除了战前协商、语音聊天、内部交流很重要,完美的合作更是必不可少。

在社交游戏中,团队的价值也非常大。团队也能成为一种强大的玩家滞留机制——因为不想让队友失望,玩家会回归游戏。为什么SNRPG中的“部落”执行方式如此无力,如此自私?这真成谜了。

外交

在任何多人游戏里,玩家都会形成同盟关系,所以外交就很重要了。以经典桌面游戏《Diplomacy》为例,所有玩家的力量都是相当的,极少有凭一己之力就战胜对手的现象存在。结盟是关键。另外,没有什么共同胜利这样的东西存在,所以在必要的时刻,你也可能不得不暗算你的盟友。

结果就是,玩家之间滔滔不绝——你必须引诱你的同盟相信你、说服你的同盟站在你一边,虽然那时你明明是在暗中置他于死地;同时,你还要估计同盟背弃你的可能性;你也得试着在敌人的盟友面前中伤敌人。《Diplomacy》这款游戏在策略和战术上还是有相当的深度的。不过关键还是在于谈判,那些雄辩之人往往胜过初学策略的菜鸟。

City-of-Wonder(from friskymongoose.com)

为了外交,游戏必须既允许玩家互利互助,也鼓励暗中加害,绝对不能像模拟社交经营游戏那样,居然有个得了“孤立并发症”的系统存在。诚然,一些游戏(如《City of Wonder》)允许玩家“攻击”其他玩家(SNRPG当然也允许)——但这类游戏不允许结盟、战略合作或者联合行动等等。

商贸

因为贸易在游戏中非常重要,所以需要保持一定的不对称性。在Edgar Cayce的经典卡片游戏《Pit》中,因为卡片是随机分配的,所以玩家要努力收集垄断不同类型的卡片。在大多鼓励贸易的游戏里,通常有几种不同的资源,玩家可能只拥有其中几样,所以就必须与其他玩家做贸易,以换取你所缺少的资源。

贸易与外交相似,也是让玩家有了相互交流的理由——决定贸易政策、寻找贸易对象、商谈价格、甚至是建立长期贸易关系。模拟社交经营游戏只能说达到了一点——允许玩家互赠某些物品,即鼓励玩家之间的物品交换。但这只是一种点对点模式,针对的是增加Facebook的交友请求,并不是为了刺激交易行为和玩家间的交流。

资源竞争

在许多游戏里,资源竞争是玩家互动的重要元素。在多人模式下的RTS游戏中,战争的导火线往往是被一种关键资源的采集权点燃的。

但“资源竞争”可能比字面上的意思还要宽泛一些,交非只有资源才会引发“资源竞争”。像《Agricola》或者《Puerto Rico》这类“行动选择”桌面游戏,每一回合可能发生的行动类型是有限的,同时有些行动会略过。

在《Agricola 》中,一个玩家做出了一种行动选择,意味着其他玩家只能做其他选择(所以玩家的“行动选择”也成了实际上的一种“资源竞争”);在《Puerto Rico》中,所有的玩家都要做出最损人利己的选择。在Steam网络对决平台上,因为游戏的平衡是通过竞拍每一回合的最先入场权来实现的,这使玩家很难估计自己投标的代价和收益是否划算,所以只能先下手为强了。

无论何时,资源、机遇或者其他受限物品,如果玩家在最佳等级时不能全部得到,那么玩家在阻碍其他玩家得到关键物品的同时,还不得不与其他玩家互通有无。

等级系统

很少游戏是带有清晰等级系统的,但这个概念非常适用于描述社交关系图。在PBM游戏《Renaissance》中,一开始,新玩家几乎没有什么资源,但如果能发誓效忠于某个强大的领主或者附庸于某个已存在的贸易商行,菜鸟也能进步神速。在《Slobbovia》中,占领一定领地的玩家必须把一部分领地的控制权转交给委任的副指挥官;如果副指挥官不满总指挥官的行动,他有权宣布独立。

等级有助于同化新玩家、长期交流、等级培养、团队合作。因为玩家的等级一直在变动,所以像有权宣布独立这样的额外优势可以使等级分化严重的游戏的“团队”活动更顺畅些。

表现

在非数字RPG中,玩游戏的乐趣主要来自操纵玩家角色:以角色的意志来做决定、体验角色所处的幻想世界、以角色的身份行动发言。

在一些类型的RPG中,如LARP、独立叙述RPG、剧情游戏和jeepform游戏,“游戏”和“电影”的界线模糊到连“角色扮演” 和“行动”都很难分清。

在这种情况下,角色扮演就不只是代偿性体验了,还应该包含自我炫耀、招待好友。玩笑聊天、制造惊喜和即兴合作也很重要。

然而,这种表现性操作却不能像桌面RPG那样随意自由。在老Sierra的商业在线服务网站上,最受欢迎的游戏之一是《Acrophobia》。

这个游戏很简单——每一回合,bot随机生成一串首字母缩略词(由一组词中各主要词的第一个字母或前几个字母缩合而成的词)。玩家要根据这个缩略词自创一个连贯或者幽默的句子(句子中的每个单词的道字母组合起来后就成了这个缩略词)。

所有玩家都造完句后,就把各自的句子公布出来。然后玩家不记名投票选出他们最喜欢的句子(自己的句子除外)。几个回合后,累积得票最多的玩家获胜。

在这个游戏中,玩家获胜的方式是想出被其他玩家认可的最连贯、最幽默的句子。尽管游戏的本质是限制性的、形式性的,但表现性仍是其精华所在。

表现性游戏在本质上绝对是社交性的。这种游戏方式可能只存在于在线多人游戏中,在线游戏非常适合这种玩法。社交关系图的存在使得玩家可以更容易地与真正的好友一起游戏、更有效地激发玩家的表现性游戏。然而,社交游戏不仅不支持这种表现,还戒绝了能促进表现的交流活动(信息和聊天,除预定格式语句外)。

结论

近几个月以来,社交游戏的月活跃用户量有所下降。有些人就开始讨论,社交游戏的已经从盛世走向式微了。所谓事无千般好,花无百日红——毫无疑问,社交游戏的新鲜感也有过时的时候,而且越是新鲜的东西越是容易过时。在我看来,这也是暂时的。毕竟太多游戏存在相似性。一旦一款社交游戏开发出了前所未有的新花样,就足够使这个领域恢复生机勃勃的面貌了。

新花样的来源还处在揣测阶段,但在我看来还是很明显的——加强社交性玩法,这就是硬道理。

作为天生的社交媒体,社交游戏确实要名符其实。真正的社交游戏不只是为了商业目的而开发社交关系图,更是利用社交关系图为玩家创造出独特而有趣的游戏玩法。

社交游戏必须擅长社交之道。

篇目4,从小群体玩家看社交游戏设计

作者:Brian Poel

有人称许多社交游戏都怂恿(或强迫)玩家邀请朋友加入自己的阵营,但却并未提供鼓励大家欢聚游戏的有效方式。玩家时不时在涂鸦墙发布的贴子或者推送信息,请求好友帮忙搜集最新的“装饰品”以完成任务,这种方式其实只能反映玩家社群协作性和互动性的冰山一角。社交游戏据称可为玩家创造互动合作体验,那么我们应在哪些方面扬长避短,根据彼此熟悉的小群体玩家特点设计游戏?

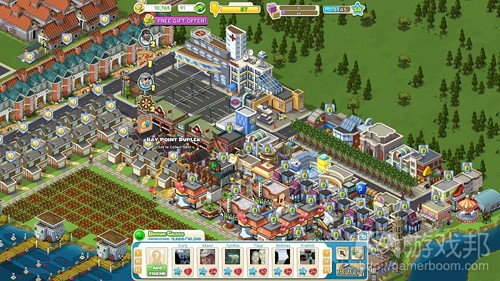

cityville(from gamersunite.coolchaser.com)

大群体中的小帮派

虽然我对“搜集装饰品”这种机制有点不屑,但还是得承认它实际上催生了一种有趣的小团体行为——那些活跃玩家因彼此互助而创建了一个小帮派,他们与大量的非活跃玩家之间形成了鲜明对比。随着时间的发展,这些玩家就可以分辨出哪些好友是自己可以救助的对象,哪些是可有可无的朋友。他们的游戏行为也就演变成了一种“团体活动”。

Like按钮

在我的游戏玩伴中,有些人已经养成了每发送一个任务道具请求,就在涂鸦墙上“Like”该消息的习惯。当他们整理原来的贴子时,也会添加一条评论,声明自己还需要多少个“装饰品”才能完成任务。这是一种很有趣的求助广告,同时也有助于告知众人哪些人已对其伸出援手。我们并不是在布道说教,鼓励大家在私底下互帮互助,发扬做了好事不留名的传统美德,而应该认识到,这种行为可以让玩家通过好友的好友,与同样活跃在这款游戏中的其他玩家建立新的好友关系。

互惠主义

有些权威人士称这种社交互动行为“很邪恶”,因为它让玩家将好友视为一种可剥削挖掘的“资源”来利用,而且它还让玩家产生一种心理上的互惠期待;社交游戏中的虚拟礼物并非免费的午餐,它总会让玩家因“欠对方人情”而不得不投桃报李。

在这一点上,我也承认这类游戏确实让人们产生了一点社交压力,它也是这种互惠互利行为的“阴暗面”,但我还是更乐于从光明面来解读这种现象。与他人玩游戏其实比独自玩游戏更符合人的天性,它可以产生更多快乐和难以捉摸的愉悦感,同时也更易带来丰富的游戏体验。玩家知道自己在游戏中帮助了好友,同时也明白对方也会有所回报,这让他们产生了一种达成共识的责任感,并因此而获得成就感和满足感。

我认为目前的社交游戏在促进好友相互影响上所发挥的作用仍然有限,究竟怎样才能在一个“大型社交”游戏中创造一种亲密感呢?

个人交际圈

因为有了好友的支持(游戏邦注:尤其是关系非同一般的好友),整个社交游戏也就会对玩家产生非凡的意义。想想看,在《CityVille》这款游戏中,好友在你的城市中开店做生意,而且还为他们的商店取了极为搞笑的名字,这种感觉的确妙不可言。我真的很喜欢好友在我的地盘上打下他们自己的“烙印”,也很乐意在他们的城市中贴上我的建筑标签。

依赖感

这方面的典型是我最喜欢的一款非Facebook游戏《GoalLine Blitz》。它是一款足球游戏,其中有许多球员均由玩家操控。在一个公开的团队竞争环境中,你的成功与否取决于球队中其他玩家的表现。这就在玩家之间创造了一种极为强列的依赖感和互惠心理,以及一种强大的共荣共存的游戏体验。

存在感

在一些游戏的大群体中,玩家角色的存在性很容易被边缘化或者淡忘。所以理想的设计原则应该是最大限度地减少这种影响,或者创造一个严格限制标准,以免这种情况发生或者持续恶化。

kingdoms-of-camelot(from insidesocialgames)

在《Kingdoms of Camelot》(游戏邦注:以及其他题材类似于《Travian》的游戏)中,它的大型竞争机制设计主要考虑了超级公会之间的决斗这种情况。因为这种机制,玩家群体中难免会有领袖脱颖而出,而其他玩家则沦为默默无闻的小角色,失去了当初作为“基层人员”而为集体做贡献的那种热情。

对我来说,这种集体贡献的二八分配法则缺乏真正的合作性,开发者在设计过程中就应该考虑到玩家群体的最大规模限制,同时也要兼顾群体中每一名成员心里的参与感,以及他们渴望被其他成员认知的存在感。

需要指出的是,搜索维基百科和谷歌,就可以发现有些心理学研究已针对最佳团队成员数量的问题展开探讨。所以开发者应根据最理想玩家数量设计游戏,以保证玩家的参与度和活跃频率,不过这种方法可能更适用于一些针对细分市场的游戏,而非Zynga旗下这种老少皆宜、用户广泛的大众社交游戏。

异步玩法

我曾听说不少硬核游戏开发者称Facebook社交游戏未来发展趋势之一就是结合实时玩法,或使用Unity等高级的3D开发技术。但我认为这种说法多少忽略了社交游戏最重要的元素之一——与好友在异步状态下玩游戏。异步玩法不需要用户与好友在实时环境中共同参与游戏,但却仍然不失彼此互助之感,这一点实在很神奇。

过去的游戏玩家曾使用邮件玩角色扮演游戏,后来又通过在BBS发贴玩游戏,到今天还是有人通过电子邮件玩游戏。早期的棒球游戏玩家通过实体邮件进行互动,尽管这个行业早已充斥互联网和服务器等技术,但这种游戏仍然存在固有的异步特点。还有一种情况也很常见,我们常在第二天讨论昨天晚上看的电视节目内容,这也算是一种“异步”娱乐体验。

异步玩法具有一种悠闲而不会产生紧迫感的优点,它应该为开发者所推崇而非因技术局限性而将其抛弃。异步玩法本身就是一种充分、完整而有趣的游戏特点。

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

篇目1,What Makes Social Games Social?

by Matt Ricchetti

When people think about online social gaming, two broad categories of games immediately spring to mind: casual social games and hardcore MMOs. Despite the criticisms leveled by traditional game designers at casual games for their Skinner Box-like appeals to our core psychic compulsions, these games have become wildly popular on Facebook and mobile devices. MMOs, while never as broadly appealing, enjoy multi-year runs and rabidly loyal user bases. One common contributor to the success of both types of games is their unique social mechanics, which might be summarized as follows:

Casual social games:

* Inviting “neighbors,” sending gifts, visiting your friends’ playspaces

* Asynchronous play with asymmetrical, loose-tie relationships

Hardcore MMOs:

* Forming parties and joining guilds, chatting with guild members, coordinating real-time group battles

* Synchronous play with emphasis on symmetrical relationships that build strong ties

As a current designer/producer of hardcore strategy MMOs at Kabam and former designer/producer of casual social games at Zynga, I’ve become intimately acquainted with both sets of social mechanics. And I find both are very useful in developing sticky, engaging gameplay experiences. Neither is necessarily better than the other.

In fact, as free-to-play (F2P), online, multiplayer experiences make up an increasingly large share of the overall games market, we’re seeing titles emerge that mix and match social mechanics from both the casual and hardcore lineages to great effect. League of Legends is a great example of this: Riot’s DotA redux came from out of nowhere to make tens of millions of dollars by combining social mechanics from MMORPG PvP battles, RTS duels, and more casual F2P games to create an entirely new genre, the multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA).

Much of this evolution of what comprises “social” is being driven by the F2P business model itself. Traditional retail games equate to a single consumer decision: to buy or not to buy. F2P games, on the other hand, feature an ongoing courtship between the player and the developer. Because of the low barrier to entry, players are inherently less committed to any given F2P game. This means developers and publishers must do everything they can to keep players engaged deeply and regularly with their games. This can be done with core gameplay and an effective monetization system; the opportunity cost for leaving a game in which you’ve invested substantial time and money is high.

But “crowdsourcing” engagement and retention to the players themselves via compelling social features remains one of the surest ways to make a game both sticky and fun. A single-player game is a game, but a social game is a community, with all the fascinating human relationships one expects: competition, collaboration, peer pressure, rebellion, jealousy, compassion, and more. The difference between playing Scrabble against the computer and playing Words with Friends is the difference between killing time and a pop culture phenomenon.

So, for today’s F2P online social games, “social” is about the user experience AND about business — the two are inseparable. Game designers must determine which social mechanics fit their game’s target market, gameplay, and business model. Whether these mechanics are traditionally found in casual Facebook games or hardcore MMOs is irrelevant.

Instead of viewing social through this limited, binary lens, this article will analyze player interactions using a set of three general heuristics. The advantage of this approach is that these heuristics can be applied to any online multiplayer game. Freed from a specific game design, their functional value becomes more apparent. Developers can then choose the interactions they feel will best serve their game’s design.

Three Heuristics for Categorizing Social Mechanics

Of the three social mechanics we’ll examine, one relates to the timing of social interactions and two involve the type of social relationship. Together, these mechanics encapsulate the social interactions of most online games:

* Synchronous vs. Asynchronous player interaction: do interactions occur simultaneously in real time or at different times as in a turn-based game?

* Symmetrical vs. Asymmetrical relationship formation: does forming a relationship require input from both parties or can they be formed unilaterally by a single party?

* Strong Tie vs. Loose Tie relationship evolution: do relationships tend to become deep and long lasting or are they more likely to be light and transitory?

Let’s break down each of these heuristics in turn.

Synchronous vs. Asynchronous

The stereotype is that MMOs feature synchronous, real-time play while casual social games are asynchronous with interaction occurring at disconnected times. However, all MMOs also feature important asynchronous features (in-game messages, for example) and some Facebook games employ synchronous features (such as chat). Rather than an absolute proposition, current social games tend offer a mix of synchronous and asynchronous interactions. Some games may highlight one or the other, but there are many that utilize both to establish a richer layer of engagement and retention.

Synchronous Interaction

The concept of synchronous gameplay is intuitively obvious — players interact in real time rather than taking turns. Examples of synchronous social interactions include text chat, voice chat, video chat, and player vs. player (PvP) battles (yes, PvP is a type of social interaction!). Synchronous interactions can scale from two players head to head (e.g., whispering and duels) to large groups (e.g., lobbies and raids).

Let’s look at chat specifically as it is a powerful synchronous tool for player engagement and retention in both casual games and MMOs:

* New players use chat make friends and ask basic questions

* xperienced players use chat to brag about in-game

accomplishments and form actual friendships (usually while killing time between events)

* Hardcore players use chat to coordinate complex group (e.g., guild/alliance) play and manage intense politics and rivalries

Whether it’s used to run a major guild in The Old Republic or help finish a badge book on Pogo.com, chat has a similar effect: boosting player engagement and facilitating long-term retention. When there is a real, vibrant support community present, players come back to a game more often and are less likely jump ship for another game. At Kabam, we’ve found chat invaluable as we’ve sought to bring more hardcore aspects to Facebook and web gaming — which we’ll discuss later.

Asynchronous Interaction

The term “asynchronous game” might at first conjure images of something slower or less robust, but asynchronous games can be just as engaging as synchronous ones — think of playing chess with a friend or Diplomacy by mail, for example. Asynchronous social games come in different basic flavors, with some of the more common being:

1. Turn-based shared games: Examples of this genre include the With Friends games and one of my favorites, Carcassonne. They work well socially because:

* Each move is a mini game

* There is social pressure to come back and complete your next turn

* Challenge of head-to-head competition

* Bite-sized gameplay is easy to fit into schedules

* Players can play multiple games at once

2. Turn-based challenge games: Essentially, this works out to be two separate matches: I play your AI and then you play mine; aggregate score determines the winner. A good example is the Bola soccer game on Facebook (which literally mirrors the traditional home-and-away format of international soccer matches). They work socially because:

* Social pressure to return challenge

* Head-to-head competition

* Less waiting than shared turn-based since each player can complete their entire game independently

* Different strategies for attack and defense enrich experience

3. Score-based challenge games: This is the traditional “beat my high score” format as exemplified in Bejeweled Blitz. These games work socially because:

* Social pressure to return challenge (one-upmanship)

* Head-to-head competition and often game-wide leaderboards

* Less waiting than turn-based since players can try for their high scores anytime

* On the flip side, these types of games can be less interactive

4. Open-world asynchronous games: In many ways, this is the standard Facebook game model, used in games like FarmVille and many others. It’s also the model for newer games with deeper social interaction such as Empires & Allies and Backyard Monsters. They work socially because:

* Model supports variety of game modes, including both single-player and multi-player PvE and PvP

* Can approximate MMO experience without incurring the technical challenges of real-time play (i.e., provides the living, persistent world of an MMO)

* Still offers convenience of more casual games — can play at different times and for short bursts

Symmetrical vs. Asymmetrical

Perhaps the best example for understanding this heuristic is the formation of social connections in Facebook versus Twitter.

Facebook social relationships are symmetric: I ask to be your friend and you must agree in turn for the relationship to exist:

* Core social unit: “Friend”

* Pros:

—Mutual acknowledgement breeds trust

—Allows for deeper sharing

* Cons:

—Site interaction limited to friends

—Friend relationships require (sometimes complex) management tools

Twitter social relationships are asymmetric: I can “follow” anyone I want, without their reciprocation:

* Core social unit: “Follower”

* Pros:

—Allows for widespread broadcasting

—Facilitates rapid dissemination of information

* Cons:

—Less investment in core social unit

—Can be less private or more spammy because communication filters are less sophisticated

Examples of symmetric social interactions in online gaming include friending, neighbor systems, gifting, trading, and private chat on an individual scale and parties, alliances, and manual multiplayer matchmaking on a group scale. Asymmetric social interactions include following, broadcasting, tweeting, and blogging on an individual scale and public quests, factions, and random matchmaking on a group scale.

Let’s take a deeper look at a few examples of symmetric and asymmetric relationships in online games.

Symmetric Interactions

A classic example of a symmetric relationship in online gaming is the MMORPG party. Forming a party in an MMORPG requires explicit consent from both the inviter and the invitee, the assumption being that the inviter wants control of who exactly he or she goes adventuring with.

While this means the invitee is sometimes subjected to a disappointing lack of invites (or a pile of ignored requests) it does mean the inviter can separate the wheat from the chaff in composing their party. This ultimately results in a deeper bond between party members, creating a tangible “us vs. them” mentality during PvE, bringing out effective class combos and facilitating the trade of level appropriate items and information.

Although Facebook games are less known for such symmetric relationships, they do exist in many of the platform’s games. The neighbor system prevalent in games like FarmVille, for example, is a symmetrical social relationship. Even players who are in same game and are already FB friends still need to become “neighbors.” This additional social hurdle creates an ongoing “friends with benefits” interaction where players send more gifts to each other and help each other unlock “social gates” (e.g., “You need five friends to staff this building,” or “You need 10 keys to unlock this door”).

Asymmetric Interactions

Facebook games also feature numerous asymmetric social interactions. Instead of neighbor systems, many games simply add your Facebook social graph directly to your playspace without requiring the permission of your friends (e.g., Bejeweled Blitz). In our Kabam game Dragons of Atlantis, players can select any Facebook friend to serve as a general in their army, even if they’re not actively playing the game.

These types of relationships are admittedly shallower than the neighbor system above, but because they are so broad, they lower barriers to interaction and create a high-density of ties among the games’ players. In the Bejeweled Blitz example, it’s too important to let the player see his friends’ high scores to ask them for symmetry. The game just wouldn’t work without a highly visible leaderboard. In the Dragons of Atlantis example, invite a non-playing friend to be a general has the advantage of exposing the game to potential new players in a personalized way via a wall-to-wall feed.

Asymmetric relationships also exist in MMOs. A great example of this is the “public quest” feature in Warhammer Online. This type of group PvE was specifically designed to avoid the normal hurdles of symmetrical party formation by automatically creating a transient party of all players who are near a public quest site. If a dragon is terrorizing the area, for example, anyone who comes within a certain range is automatically considered to be participating in the public quest to kill it. Players can quickly and easily get a taste of group play and then go their own ways afterwards. The low social barrier allows for more frequent cooperation, even if it means forgoing usual party staples like chat and item trading.

Strong Tie vs. Loose Tie

Symmetry vs. Asymmetry describes how relationships form but doesn’t necessarily dictate how they evolve. For example, people who meet in the “Long-term Relationships Only” area of an online dating site are more likely to get married than those in “Casual Encounters” — but that’s not always the case. Ultimately the relationship depends on what happens after the first meeting. Strong tie vs. Loose Tie is a simple heuristic for gauging the evolution of a social relationship with a focus on depth of interaction.

Examples of strong-tie gaming relationships range from 1:1 scale (two-player co-op play and RPG parties) to group scale (guilds, alliances and leagues). Examples of loose-tie relationships also range from 1:1 (in-game neighbors, for example) to group scale (factions, classes, and tournaments).

Factions vs. Guilds

Strong ties are usually symmetric — which makes sense as the requirement for symmetry usually means the relationship was designed for deeper sharing. Conversely, loose-tie relationships are usually, though not always, asymmetric.

A look at guilds versus factions provides a classic example of strong versus loose ties in MMORPGs. A player usually chooses a faction at the very beginning of a game on his own (i.e., asymmetrically). The faction relationship plays a role in determining core aspects of the player’s experience, like which classes are available to him, where he will spending his time adventuring, and what quests he will encounter. Socially, it works as a broad glue, separating “us” from “them” or the “good guys” from the “bad guys.” So even if a player meets someone whom he has nothing else in common with, their common faction can still be a jumping off point for their relationship.

Guilds are quite different. They usually don’t affect a player’s core experience so fundamentally, nor are they as critical in the early game. But once a player gets involved in a good guild (via symmetric acceptance), the social benefits it offers can literally be game changing. Guilds are where players trade items, learn optimal strategies and tactics, receive buffs and other benefits and, most of all, make friends. I can tell you a variety of personal things about the folks in my Chronicles of Merlin alliance (i.e., guild), despite not knowing any of their names or having ever met them. We even have our own Facebook page and interact with one another outside the game.

Factions vs. Neighbors

Loose-tie relationships aren’t always asymmetric. Facebook neighbors, mentioned above, are in fact a good example of symmetric loose ties. The neighbor relationship is primarily designed for sharing gifts and small amounts of viral currencies, not for extensive chatting, strategizing, or cooperation. The reason for symmetry in this case is simply to better leverage the virality of the Facebook platform. Forcing players to confirm neighbor relationships engages them in sending requests to each other, an important behavior to encourage early in the players’ lifetimes.

Class specialization

Loose ties don’t always equate to low game impact. As mentioned above, factions can play a major role in shaping a player’s experience. Another ubiquitous (to RPGs at least) example of a loose-tie relationship is class specialization. Class specialization is certainly social; it forces interdependence in group combat and defines the classic MMO tank/healer/DPS triad.

But it isn’t a strong tie. Just because I’m a mage and you’re a mage doesn’t mean we’re going to be fast friends. Rather, like factions, class specialization is a broad, constant factor in shaping gameplay outcomes. Interestingly, because class specialization is asymmetric (no one consents to my class choice), you can end up with too many players of one class. Although most games are balanced such that this does not occur on a global level, most of us have experienced the unfortunate PvP battle where our side was repeatedly mowed down due to a lack of “___” or too many “___” (fill in the blank with any of the roles: tank/healer/DPS).

Case Study: Kingdoms of Camelot

Overview

In order to better explain how these heuristics can be used to understand social mechanics, I’m going to apply them in detail to a game I know well, Kabam’s Kingdoms of Camelot.

Our goal when we started Kingdoms of Camelot was ambitious: to create an MMO that also worked as a Facebook game. We wanted to combine hardcore strategy gameplay with Facebook’s built-in social/viral channels and a deeper level of free-to-play engagement and monetization.

By a combination of skill, luck, and perseverance, we hit our goals and created one of most successful games on Facebook. Still going strong after more than two years, Kingdoms of Camelot is now one of the top strategy franchises on any platform, with 490,000 monthly active users as of this writing, so we must have done some things right — particularly on the social side.

Let’s look at what went well and what we could have done better for the both game’s MMO and Facebook social components.

KoC as a Facebook Game

The core of KoC works fairly well as a Facebook game, since it can be played as a single-player, quest-driven city builder. Key social mechanics that work well with Facebook include asynchronous combat, a friend ladder with invites/requests, resource gifting, and viral feeds for things like building help.

Combat (asynchronous, asymmetric): Combat in KoC is asynchronous: the attacker initiates a battle against any player (even one who is offline), his armies march to the target on a map, the battle ensues, and results are then sent as reports to the inboxes of both players when it is complete. This simple, timer-based system supports bite-sized Facebook play patterns while still allowing for engaging PvP.

KoC’s combat is also asymmetrical in that a player can choose any target. The world is a real, open battleground and doesn’t use any lobbies or matchmaking like some PvP systems. This “always on” feature is mitigated by the fact that beginning players are protected from attacks and any player can hide his troops in a “sanctuary” to prevent losing them when offline.

Invite/Request system (asynchronous, symmetric): Like all Facebook games, players send friend invites and build a friends ladder. You can invite friends to be Knights that lead your armies and you can send gifts of resources and troops to friends. Players can interact with friends anytime, even when offline (asynchronous), but friends must accept invites and requests (symmetrical).

Social feeds (asynchronous, asymmetric): KoC’s social feeds are similar to other Facebook games but focus on material, in-game incentives (vs. “bragging”). For example, players can share a Merlin’s Magical Boxes token for a chance to win free virtual goods or post viral “Build with Help” requests that Facebook friends can click through to reduce the time to construct buildings, conduct research, or train troops.

Takeaways

What we did well:

* Evolved Facebook city building games by adding in asynchronous combat

* Leveraged integration with core Facebook channels for modest virality/engagement bump

Where we could improve:

* Facebook channels are not as deeply integrated as some games

* No “friend visits” or vanity social status

* Friend invites and gifting are not tied to game progression or in-game resources

* Feeds are only utilized for some features, limiting virality

Beyond its core Facebook integration, KoC’s innovation is that it plays like a real MMO: emergent behavior in both social and combat features drives deep immersion. The game’s combat system features open-world group PvP, tournaments, and leaderboards just like a client-based MMO. Other traditional MMO social features include alliances, chat, messaging, and trading.

MMO combat (synchronous, strong tie): Because KoC’s combat system is based around open-world group PvP, it drives synchronous, strong-tie social interactions. Even though any individual attack is asynchronous, alliances band together to conduct planning and strategy and coordinate waves of attacks in real time.

The game features regular tournaments with rewards and new worlds where players can start over, both of which encourage repeat play while refreshing PvP rivalries. Individual and alliance leaderboards provide a measuring stick for combat might, fueling a strong sense of both social status and competition.

Alliances (synchronous, strong tie): The game’s alliance (guild) structure and social tools enable extremely strong ties.

A feature known as “alliance diplomacy” allows alliances to set other alliances as friends, enemies, or neutral, giving rise to meta-alliance social play that is symmetrical (both alliances must agree to a diplomacy level), asynchronous (diplomacy doesn’t need to be done while both parties are online) and strong tie (the jockeying for position and status never ends).

Social status and power disparities within an alliance also generate strong ties. Each alliance has several leadership roles for elite players who serve as Chancellors and Vice Chancellors and decide who’s in and who’s out of an alliance.

Being rejected from an alliance can be like being rejected from a prestigious college or job: it can fuel a player’s game-long quest to prove the alliance wrong by forming a rival group that is more powerful.

Alliance-specific “slices” of other synchronous, strong-tie social tools such as chat, messaging, and battle reports also allow alliances to communicate and strategize while keeping the information “in the family.” For example, how players in one alliance describe players from another among themselves can be quite different from how they socialize with them externally.

Chat (synchronous): KoC chat is a key synchronous social feature that makes the world feel more dynamic and alive in real time. Three levels of chat allow players different ways to communicate. Alliance and private chat channels (symmetric, strong tie) foster relationships during the down time while waiting for builds to finish. Global chat (asymmetric, strong or weak tie) lets beginners ask questions while encouraging the trash talk that drives enmity between alliances.

Alliance chat in KoC.

Messaging and Trading (asynchronous): Messaging (asymmetric, strong tie) is used for communicating organizational and logistical info: alliance rules and announcements, battle plans, enemy information. Resource trading (symmetric, weak tie) adds an additional layer of non-combat, social interdependency as players buy and sell goods with each other.

Takeaways

Kingdoms of Camelot brought synchronous, strong-tie MMO play to Facebook social gaming to create a new experience on the platform.

What we did well:

Layered synchronous MMO PvP combat onto a Facebook game

Focused on strong-tie alliance relationship as gameplay foundation

Supported combat system with social communication tools that leverage both synchronous/asynchronous and symmetric/asymmetric relationships

Where we could improve:

Deepen combat system with additional strategy/tactics (e.g., support group PvE in addition to group PvP)

Develop social structure of alliances even further (e.g., support broader play styles beyond attacking and sharing resources)

Provide additional communication tools (e.g., offline notifications for key events/interactions, additional channels for communication between alliance officers and other subgroups, etc.)

Conclusion

As the online game landscape becomes less black and white, social innovation requires more work. When we established Kingdoms of Camelot as an early hardcore MMO on Facebook, we had a clear point of differentiation from previous games. Since then, the Facebook landscape has become more MMO-oriented, and there are more PvP games available. Even heretofore strictly casual game developers like Digital Chocolate and Zynga have joined in with titles like Army Attack and Empires & Allies.

Map screen in KoC.

At the same time, the non-Facebook landscape has become more “casual” (or at least more broadly social). Players now expect ALL online games to offer full multiplayer functionality and interactive support features. This is evidenced in recent developments in AAA MMO social mechanics.

For example, World of Warcraft made major updates to its raiding features with Cataclysm to make group PvE less onerous and more accessible. Star Wars: The Old Republic, the latest and greatest MMO on the block, allows players to work on their personal class quests even while adventuring in mixed-class parties.

This is an important concession to social accessibility, as class story quests are a key differentiator in SWTOR.

Lastly, the free-to-play business model is really flexing its gaming muscles. Most of the older subscription MMOs — Dungeons & Dragons Online, Age of Conan, Lord of the Rings Online — have all moved to F2P. Even some non-MMO, hardcore games like Team Fortress 2 are now F2P as well. In fact, Sega just announced the first true F2P title for the PlayStation Vita, Samurai & Dragons, based on the top-grossing F2P iOS game Kingdom Conquest.

This diverse landscape means that it’s harder to differentiate your social game (or should I say “your game, socially”) from the competition — yet more important than ever to do so.

Using These Heuristics

The three heuristics we’ve described are not a panacea for all social game design — but they can be very instructive. You can use them to both help evaluate existing games or design new ones.

For existing games, break down your social mechanics against these heuristics to determine your true mix of synchronous/asynchronous, symmetrical/asymmetrical and strong-tie/loose-tie relationship features. Ask yourself if your approach fits the needs of your audience, gameplay, and platform. For example, an older audience might not take to synchronous play, while a younger audience might demand it; a “twitchy” arcade game might not be suitable for strong-tie relationships; or a mobile game might be most social if relationships were low friction and thus primarily asymmetrical. So ask yourself: what would you change, and why?

The greatest value of these heuristics can be realized when designing new social games from scratch. Proper use can move your game beyond the binary casual/hardcore approach to incorporate novel, multilayered patterns of social interaction. It’s always easier to build a strong social layer into a new game, where it can be tied deeply into the gameplay, than to try to graft new social features onto an existing game.

In translating your business and user goals into game features, put the greatest focus on the social mechanics your particular players will interact with most often. Even a well-designed social feature will have a smaller impact on users — and ultimately your business — if it is buried in the interface or peripheral to core gameplay.

Also remember that a mix of social mechanics often yields the strongest results. Kingdoms of Camelot likely would have been less successful if we had used elements solely from the Facebook or MMO side of the social mechanics ledger. A mix of features leveraging Facebook channels for viral acquisition and early retention plus MMO social interaction for deeper engagement and monetization was what worked best for us and our players.

Finally, remember that these heuristics are rules of thumb, not absolute guidelines. Learn the rules then break them as long as it works for your game and your audience. Good luck!

篇目2,The Soapbox: What MMOs could learn from social gaming

by Eliot Lefebvre

I mentioned a couple of months ago that social gaming isn’t going to destroy MMOs. That’s good news for everyone other than Richard Garriott and Zynga stockholders. But I think taking this as a sign that we can ignore social gaming for now and forever as an aberration would be… a mistake, to put it lightly.

See, there are things that social games do even better than MMOs tend to. And the hint is right there in the name. No, I’m not implying that these are better games; I’m saying that social games are generally much better about handling the social side of the equation. And the MMO industry as a whole would do well to pick up on the hints.

Not everything, of course. We all have recurring nightmares about that one person on Facebook whose timeline is nothing but a series of dubious achievements in social games. But there are a lot of elements scattered throughout the games as a whole that could be oddly useful if taken as a whole.

No restrictions on helping in some way

Ms. Lady and I both enjoy playing video games. It’s part of how we became friends in the first place. Unfortunately, she and I have very different attitudes toward MMORPGs. I tend to jump in at launch or close to it, or I get thrown in by a round of Choose My Adventure. She tends to hang back until I’ve told her whether the game is worth playing or not. The problem is that by the time she finally jumps in at Level Hopeless, my level is being measured by scientific notation. She can’t help me, and I can help her only by removing the actual game and killing everything around her.

But if we played FarmVille, I could go water her crops and she could water mine, no matter what level we both were.

Most social games have some variant on this. FarmVille also lets you send presents to others and rewards you for doing so. Dragon Age Legends allowed you to recruit the characters of your friends for your party, meaning that as you play, you all have an easier time with content. Most games give you some small way that both players can derive a benefit.

Designers of MMOs have realized over the years that it’s no fun to join a game for your friends only to find that your friends have passed your level long ago, and as a result, most games have put some system into place to try to fix this issue. The trouble is that most of these fixes have still involved going back and forth with leveling, usually raising or lowering levels as necessary. There’s no tasks where two characters can provide equal aid to one another without levels needing to get in the way.

And it doesn’t need to be something major. There’s a sense in a lot of MMO design that either you’re going through an entire dungeon together or you’re playing separately, but most social games let you jump in, help someone for five minutes, and then get back to whatever you want.

Guild Wars 2 does a good job of encouraging this behavior. You’re not punished for attacking the same target as another player, and it winds up helping both of you out in the long run. It’s just a quick chance to help someone else out, and you both get a boon from it.

A mercantile relationship with easy mutual benefit

The healer in your group is fundamentally there because you need him. Sure, you like him. He’s a cool guy, you talk out of game, he sent you some nice recipes earlier in the month, and you pointed him to a good job in his area. You are definitely friends. But you met because you needed a healer and he fit the bill, and his function in the game is to keep you alive.

There’s nothing shameful about that. When I’m in a group, I’m there to perform a role, not deliver cutting insights about design style. Relationships in games like this are based on mutual benefit at some level, even if in the end you wind up being friends first and MMO buddies second.

Here’s the thing: No one likes to admit this. We have this image, encouraged from several sources, that your groups in MMOs are supposed to consist of your friends first and functional allies second or third or possibly never. This is despite the fact that the game is clearly encouraging you to go ahead and play with people who provide you a tangible benefit, since very few games have a system for clearing content based on shared social interests.

Social games engage in no such pretense. You need more friends playing this game to do this, and that’s the end of the discussion. Get more friends. Give away these gifts to get a prize. Help others specifically because that helps you in the long run.

Part of why no one cares about this is that by definition, the people you are foisting this upon are already your friends. But another part is because the game just makes it transparent that this is what you’re doing. You’re helping others to help yourself, and that’s not a bad thing. Everyone gets something.

This point and the previous one could easily combine into some useful methods of social interaction without requiring dedicated group content. Imagine a buff that you can receive only if you give it to someone else as well, or an experience boost received for providing a minor service for another player. Imagine if visiting the properties of your in-game friends gave you a quest to clear out nearby animals and doing so gave you experience and boosted some in-game stat for them as well. These are all ways to interact and benefit without requiring a big chunk of time or requiring a formal group together or pretending that you’re helping just out of pure altruism.

Sharing the cool

Social games follow an evolutionary path not unlike a virus; they require you to spread and advertise everything you’ve done therein because their best chance of making money involves a lot of people being aware of the game. So each game floods your status page with updates about what, exactly, you’ve recently accomplished in the game.

The side effect is that people just see that you’re having a lot of fun. And that’s something that I think MMOs have frequently missed in the rush of design trends and philosophies and so forth. At the end of the day, the great part of playing an MMORPG is that you can play with someone else on the same virtual playground, even if you’re not both physically there at the same time.

Over recent years games have gotten much better about reducing the barriers to entry so that if your buddy wants to join you in Star Wars: The Old Republic or Champions Online or EverQuest, he can do so now instead of when he finally goes to the store. But there’s still a persistent sense that everything cool should be restricted to you and you alone for having accomplished some great task in the game. By your dedication, you get to the fun part.

Here’s an idea — why not take a lead from social games? Why not invite your friend and give him something instantly cool, and then have him move up increasing tiers of cool as you enjoy the game? Why not reward his time by telling him cool stuff is here instead of forcing him to slog and grind to catch up with you?

The great weakness of most MMORPGs is that they ask you to suffer through a lot of work before you get to the fun. Social games throw you right into the cool part. That’s a lesson worth learning.

篇目3,Unsocial ‘Social’ Games

by Greg Costikyan

[Veteran game designer Greg Costikyan unpacks whether social games are truly social or they are not -- and having dissected the form, then leaps in with some suggestions on how to make the games more rewarding for players and developers.]

Three years ago, my friend Eric Goldberg called me up and asked me if I would be interested in working on a “social game” for a little Web 2.0 company in California he was consulting to.

A social game. Hm. That did sound interesting. I had fantasies of limited-duration, closed room live-action role playing, or perhaps multiplayer boardgames that fostered intense player interaction, or maybe something like an urban game, suitable for the Come Out and Play Festival, with players engaging with each other for extended periods of time.

Or perhaps some merger of online forum and gameplay, some elaboration of the competitive wordgames we used to play on Genie and The Well and Echo, showing off for one’s peers and preening in a social environment.

Yes, pushing the social element of gameplay could be very fruitful, an obvious and exciting extension of the capabilities of the ars ludorum. And someone might actually pay me for this?

Well, no. Suspiciously, I asked Eric what he meant by a “social” game.

After quite a bit of blather, I realized what he was talking about, and cut to the essence. “Ah,” I said. “I see what you mean. A game that is played on a social network. Is there anything actually social about it?”

You could hear the shrug on the phone. Would I like the introduction?

Sure. I needed the work.

When I was 13, and an enthusiastic fan of board wargames such as those published by SPI and Avalon Hill, I spent some time looking over a list of wargames divided into different categories — Napoleonic and World War II, and so on — thinking to myself that I wanted to find a style of game to make my one, to study more seriously and become expert on. One category popped out at me, and was what I decided to specialize in: multiplayer games.

In digital, we think of “multiplayer” as meaning anything that isn’t soloplay; in wargaming, however, multiplayer meant “a game for more than two people,” since most wargames are struggles between two opposing sides. I chose the category that encompassed games like Diplomacy and Kingmaker. They struck me as far more interesting than two-player wargames, because the complexity of interplayer dynamics produces far more variability than in head-to-head games. Negotiation, alliances, trades, and simply reading other players became important; it wasn’t all about system and the mastery thereof.

I spent many long hours negotiating, allying, backstabbing, and learning to deal with others.

When I was 14, Dungeons & Dragons appeared, an inherently multiplayer but cooperative game set in a fantasy world not unlike those of the novels I loved to read. Its

appearance spawned many long hours learning how to coordinate, cooperate, persuade, do “improv” in an almost theatrical sense, and work to shape stories cooperatively with others.

Dungeons & Dragons, in all likelihood, saved me from being a studious, depressed loner, ultimately making a somewhat charming adult out of a shy adolescent. It taught me to be a social being — not surely from any intent of Gygax & Arneson’s, but from the nature of its gameplay.

For many years, I dismissed digital games as devoid of merit, partly because of their lack of intellectual and narrative seriousness, but more importantly because of their inherently solitary nature. It was M.U.L.E. — Dani Bunten’s landmark multiplayer game for the Atari 800 — that showed me that digital games, too, could be highly social.

I moved early into designing and playing games online — even before the internet was opened to non-academic users, on the commercial online services — because online games redressed the greatest flaw of digital games: their inherently single-player nature.

And in recent years, I’ve become fascinated with the rise of LARPs, indie RPGs, and story games, because they place socialization among the players, improv, and the assumption of character, front and center in play.

Social games — correctly defined — are important; and games that have hooks for socialization are, I think, our best bet for the creation of true art in this form.

It’s a pity that “social games” are so unsocial.

One of the fundamental contradictions of the human condition is that we are simultaneously individuals and social beings. We are each lost in our own heads, with only the limited bandwidth afforded by expression and language to allow us to understand each other. We typically strive to achieve our own needs and desires, often at the expense of others; we are atomistic individuals, striving for our own benefit in a Randian sense.

And yet we cannot grow without the nurture provided by our parents, are driven by our needs to find sexual and emotional partners, have built civilizations that depend utterly on cooperation and exchange, and are most often happy in the companionship of friends.

We are both free and members of societies, dispassionate observers of our surroundings and passionate members of groups, freethinkers and partisans, competitors and cooperators.

We prize individual freedom, and also community. We solo, and join guilds. Americans, in particular, make much of the importance of individual liberty — and yet to accomplish almost anything, we need to enlist our fellows in a common endeavor.

Though ultimately we live, and die, alone, imprisoned in our individual skulls, we are inherently social beings.

And just as we most often find happiness through others — our partners and children, our friends, and the extended praise and approbation of the many — so too the best and most affecting game experiences we can have are those that involve others.

The fiero of a World of Warcraft raid successfully accomplished with your guildies; the laughter produced by sardonic gameplay in an RPG; the emotional impact of a

jeepform or story game produced through unexpected improvisation with others; the banter and play of power dynamics in a Eurogame; even the table talk and insights

into character you gain through the play of a conventional card game with friends — these are experiences to be prized.

Even for single-player PC or console games, if you try to recall the most compelling experiences you’ve had playing them, I think you’ll find that those experiences derive not so much from triumph over mastery of a system — but from a moment of insight into the mind of the designer, a grasp of what the game is trying to achieve, an insight into the game’s subtext.

That moment of epiphany, when you finally understand; that sense of engaging with the creative product of others; that sense of being part of a cultural conversation, of something that you can discuss and debate with your friends — that, perhaps, is at least as important and earning a score. In these cases, the social nature of your experience is indirect, since you experience it alone; but the experience is part of a larger, and continuing, social conversation among the players and creators of games.

If you were the last person on Earth, would you play games? And if so, would it do anything other than to make you sad with the realization of what has been lost?

The social nature of games — indeed, of any form of art — is part of what makes them compelling; and games that strike deep into social connections are often the most compelling of all.

“Social games,” then — that is, games that strive particularly to make and exploit social connections between players — have enormous potential, as forms of art.

It’s too bad, then, that few so-called social games are remotely social.

The first commercially successful “social games” were social network role playing games (SNRPGs), like the various Mafia and Vampire-themed games. Like more conventional digital RPGs, they are games in which you control a single character, with the primarily objective to level up by completing tasks of one kind or another.

They strip this down to a bare minimum — missions are accomplished by a single click, leveling up opens up new ones, and “energy,” which recharges slowly, is the main constraint on advancement, since you may accomplish only so many missions in a period of time.

In addition to mission and level advancement, SNRPGs allow you to attack other players. In an attack, a character stat (that can be improved with level) is added to the attack value of equipment, and compared to that of the defender; the winner gains EP and money, the loser loses money and health.

An additional fillip — critical to the game’s virality — is that players may use network invites to ask friends to join their clan (or mob, or what have you), and when in combat, your value is increased by the values of your friends. Thus, the more clanmates you have, the more powerful you are, the faster you can advance — and the less likely you are to suffer from the attacks of others.

SNRPGs are, in fact, completely solitaire in nature, except for the ability to attack others, and the ability to have clan mates. The idea of the “clan,” however, has no real meaning; each player’s clan list is entirely separate from every other player’s.

If I join “your clan,” this does not mean that I join also with other members of your clan; I can belong to any number of players’ clans simultaneously, and the only relevance this has is to increase of combat power of these people (and my own). The “clan” is merely a game conceit; it has no organization, no mechanism for interaction or planning, no common assets. It is nothing like an MMO Guild; it’s just a list.

Games of this type do allow you to type in messages that are seen by your clan mates, which sometimes produces weird conversational lacunae, since your clan mate may be responding to a message from his clan mate who is not your clan mate, so you see only one side of a conversation.

The main way players use this feature is to list friends of theirs who are looking for more clan mates, so you can increase your power by friending and adding them to your clan; I now have more than three hundred social network “friends” who I do not, in fact, know, and have scant interest in knowing. Their only purpose is to make me competitive in SNRPG combat.

You can argue, in fact, that SNRPGs are antisocial in nature, since the only real interaction with other players is attacking them.

At present, most social network games are, in essence, light sim/tycoon style games. You control a map on which you may build structures, place decorations, plant crops, and so on; some of the items you place produce game money, which you accumulate by clicking on the item in question after some period of time.

Sometimes, but not always, you have an avatar, who moves around, performing the “work” you request when you click on an item. You level up over time, and this gives you access to more placeable items and other content. Typically, there are badges, collectibles, and quests you may accomplish.

In other words, the core gameplay is inherently solitaire in nature; you do not cooperate with others in building your business/city/what have you, but are doing so on your own, each player in his own atomistic world.

However, social tycoon games provide many hooks for inter-player interaction, of a kind. One critical system is “gifting”; players are urged to send others free gifts, which cost the recipient nothing but provide some modest game benefit to the recipient.

In particular, the construction of critical items in a game are often gated by the requirement to have some number of a particular item that can only be received as agift, giving players a motivation to request such gifts — and, of course, to spend real money to eliminate the restriction if they have a small number of friends or are simply impatient.

Players may, of course, brag about their accomplishments, which serves the purpose of spamming social network communication channels with posts about the game, thereby helping to attract new players (a practice still encouraged by social tycoon games, despite the fact that Facebook now makes these posts invisible to non-players, thereby nerfing their viral function).

And players may “visit” each other’s maps, performing some limited number of tasks on each friend’s map. This provides some sense that other players exist in the same game world, although in truth each map is wholly independent and solitary.

If you look at the interplayer communication fostered by social tycoon games, you will see that every possible communication, every game action that a player may take relative to another player, exists solely to serve the purposes of the developers. Each communication action is designed to do one of three things: attract new players (virality), encourage players to return (retention), or encourage purchase (monetization).

Player interaction has modest, if any, impact on game progress; no impact on game outcomes; no or virtually no consequences for the players involved.

If SNRPGs are, truthfully, antisocial, social tycoon games are, truthfully, asocial; the interplayer interactions they foster are not, in fact, social in nature, do nothing to build friendships or enmity, and provide scant, if any, sense of connection to other people. They’re like soloing in an MMO; you’re aware of the presence of others, but they are largely irrelevant to your play.

Developers of social games have clearly given great thought to using the social graph to foster player acquisition, retention, and monetization; but as far as I can see, no thought whatsoever has given to the use of player connections to foster interesting gameplay. It’s all about the money, and not at all about the socialization.

The peculiarity of this is that social networks are actually far better suited than most online environments to fostering social gameplay. Messaging and chat are built into the system, and need not be separately implemented by developers; but more importantly, the social graph allows players to interact with people who are their actual friends.

Most other online environments make that difficult. For example, MMOs make it hard to play with true friends, because of their segmented nature. I may learn that you are a WoW player, and want to play with you, but find that you play on a different server from me; I’d have to start over at level 1 to play with you.

Even if I and a group of friends all decide to start out on the same server, the reality is that we play on different schedules and with different levels of intensity, so even all starting at level 1, we will soon be of divergent power, and MMOs gate content by level. If you are level 5 and I am level 20, there’s no easy way for us to play together, since progress for my character requires me to be in areas of the world that will kill your character quickly.

On a social network, it is easy to discover what games your friends play, and it would be trivial to implement systems to allow people to play with each other –reserving games for groups of friends, say, or designing systems to accommodate players of diverse power who are network friends.

Online sites that allow quick, pick-up and play games are problematic as well; it’s easy to go to a site like Pogo.com or Days of Wonder and play with strangers, but this is far less interesting and enjoyable than playing with friends. The messaging provided by social networks, and the ability to share content with others, means it should be far easier to implement games that allow play with genuine friends than on other sites.

In short, developers have learned how to use the social graph to rake in the bucks, but not how to use it to foster gameplay that is actually social.

What does “actually social” gameplay look like? It’s not very mysterious. The following is not exhaustive, but here are at least a few of the means by which social play can be encouraged.

Teams

Game Advertising Online

In a team sport, you must coordinate with your fellow team members. It is certainly beneficial if you are an excellent athlete yourself, but if, say, in basketball, you do not remain aware of where your teammates are, and be prepared to pass to them (or receive the ball from them), you will not be a great contributor to your team.

While sport is sufficiently faced-paced that communication beyond hand signals is rare, the team that coordinates effectively will, more often than not, triumph over the one that does not.

Much the same is true in any sort of team-based activity; in a team shooter such as Counter-Strike, team coordination counts at least as much as individual FPS skill.

In a World of Warcraft instance, the boss can only be overcome by excellent coordination — and the ability to confer before a battle, together with voice chat, makes interplayer communication vital.

In a social game context, teams have great value as well; they are potentially a strong player-retention mechanism, because players will return to the game, not wishing to let their teammates down. Why SNRPG “clans” are implemented in such a meaningless, atomistic way is a mystery.

Diplomacy

In any multiplayer game where players may form alliances, diplomacy becomes vital. In the classic boardgame Diplomacy, for example, all players are of equal strength and can rarely overcome a single opponent alone; alliance formation is critical. Moreover, there are no joint victories in the game (though ties are possible), so there is a strong incentive to backstab your allies at just the right moment.

The result is that players talk constantly; you need to persuade your allies to remain on board, you need to lull them into faith in your loyalty as you plot their demise, you need to try to gauge the likelihood that they are about to betray you — and you need to try to persuade your enemy’s allies that their best interest lies in switching sides. Diplomacy is a game with fair strategic depth, and some degree of tactical finesse — but its heart likes in negotiation, and the silver-tongued will more often win than the player who has memorized opening strategies.