万字长文,从不同的维度谈游戏的故事设定和意义,上篇

篇目1,故事元素在用户游戏沉浸中的效能分析

不管近的远的总能时时听到一些消息:A先生从某游戏大公司离职聚拢了三五个人开始了游戏创业生涯,而B先生则干脆从不沾边的领域大跨步迈入游戏产业也试图从顺势而为中瓜分自己的市场(特别是社交游戏和手机游戏的前期表现前所未有地降低了游戏研发的准入门槛,并且存在个人或者超小团体以创意的名义几乎颠覆了游戏的概念市场更是让整个游戏产业的制作趋于疯狂)。

有时候我们总是在想,这究竟是游戏市场规模大到随便一个群体(不管是不是标准的开发者)的任何一个探试都能轻易地切割到让各方满意的蛋糕亦或者游戏市场有着各种低成本的试错机会(比如研发经费不高,用户获得成本在可控范围)还是只是单纯地以少数几个基点(比如相对成功的开发者)为核准不断自我放大陶醉的媒介狂欢?

这样的问题多少难以回答,慢慢分不清楚到底是游戏市场的召唤力大到不可抗拒还是什么都不能阻挡开发者一颗从游戏中刨出金砖的决心(不管是模糊地看到别人的成功方向,还是觉得自己有挖掘不完的工作激情)。已经没有办法考量这算不算是一种神奇,看到了别人成功的身影就觉得沿袭很靠谱或者一个灵光闪现的想法就足够当成一根救赎的稻草,短时间内果断作出研发拍板,外表上干劲十足得让人艳羡。然后成千上万的开发者就奔上了市场暂时容量有限的独木桥,我们时常能够私底下看到各种开发者以不同的方式仆倒在盲目向前的路上(绝对大概率事件)但瞬间有人偶尔成功的消息又被当作典范偶像一般的歌颂马上以欢乐和朝气盖过了一路上所有的辛酸、失意和落魄,没有人有冷静反思的空间,看到后来者黑压压的人群和一脸庞的激动自信劲,任何的疑惑一下子就被遗忘殆尽,所有人又信心满满奔袭在疑似康庄大道上。

despicable-me-2(from polygon)

这种注定路途坎坷恶劣的丛林竞争,大部分的开发者在只是模糊辨识了一点方向就基本什么都不携带地上路了。

这让我想起了David Jones(侠盗猎车手)在谈开发者应该以什么样的态度来审慎对待自己创意设想的问题(开发者需要在投入研发以前先仔细考虑产品寿命和受众价值,如果自己四五个月后就忘了某个游戏理念就最好不要去开发这个理念,而如果两年后仍然对这个想法念念不忘并且满怀激情,那么他就知道这个想法已经成熟,可以将其转变成产品了)和现今阶段的一个比照(要么翻版或者拼凑现有相对有市场的产品设想,要么抱着自己一个拍脑袋得来的想法就果断做产品研发)就必然很清楚失败为什么总是能在最后作为一个大概率事件呈现。而其中最不能略省的就是开发者对自己想做的事情不够明朗(比如只是大体上模糊地知道自己差不多该做什么),这和我早先阅读Tess Jones做游戏和电影比照的时候有太多相似的地方,Tess Jones认为电影脚本需要一个相当严厉的制作、审核和考评过程(甚至需要介入大量的观众喜好元素,即便如此也不一定能够获得拍摄的机会)而现在基本处于大跃进状态的游戏研发(特别是以社交游戏和手机游戏为典型的轻游戏更是如此)在题材遴选和脚本撰写层面则明显不负责任许多(当然和成本投入有关,但更多呈现的是盲然和不专业性,只凭喜好和随时可能熄灭的所谓热情,随时上马一个新项目或者终止一个研发中的项目),同样在其他的附属层面也明显缺失整体考量的拼凑居多(比如声效和背景乐基本在游戏中是独立游离的,很少有能够自始至终将听觉感触当成游戏完整的组成环节)。因为门槛低的缘故,很多明显的瑕疵最后都被市场大潮表面冲刷得一干二净,也鲜少有开发者愿意去回想过去失败的症结,所有人基本都忙着一个事情:我们都处在主动或者被动的大潮中,没有任何片刻停留的心情。

和电影制作相似,好的脚本方案同样是游戏研发的出发点,而这一点在轻游戏的概念中一再被忽视(很多游戏设计基本太慵懒,转而直接借助于现有的方案模板或者进行粗糙换皮或者进行二次整合),鲜少能够为合适且惬意的出发点做探寻,反而是随便一个借力点就出发了,至于究竟能够达到怎样的终点在出发的当刻估计都来不及考虑,所有的一切都急急忙忙,盲目推崇着“唯快不破”的至高理论,以为率先迈出的这一步就一定是赢得未来世界最坚实的筹码。Thomas Grip(Frictional Games)在谈到游戏制作表现力的时候提到了游戏也许也能够追寻电影《辛德勒的名单Schindler’sList》、《肖申克的救赎(The Shawshank Redemption》那般给用户最深处的视听感触,以故事的元素(至少在脚本方案层面下更多的心血而不仅仅只是一个游戏创意的附属,甚至在程序端和美术端能否实现的双重夹击下再度扭曲,更改得面目全非,全然不知道出发点的本意是什么)去引导用户在体验当刻的沉浸(再建一个完整的虚拟世界,并试图让用户忘记除此之外的任何事物)。而这无非和现实人生相似,所有的一切都被切割为碎片再重新拼凑为每一个具有涵义的横断面去支撑玩家在不同时间长度内所能体验的每一个看起来完整的故事(符合逻辑性,比如为了完成一次药材的收集,不同的配方后面都隐含着一个独立而完整的冒险题材,都有着各自惊心动魄的背后故事),没有太明显的中止属性,都能够沿着可选择的方向做不同的延伸(玩家参与了其中的每一个进程,并慢慢对故事的当前状况,过去的脉络和未来的走向有一个概念性的认知,然后以自己已有的知识框架去探寻和验证自己在游戏中的所有的设想)。这也是Ted Price(Insomniac Games)关于用户沉浸理解力的一部分:当开发者的设想框架和玩家真实经历在游戏中逐渐重叠,此时所有玩家之前沉睡于心底的意念就会逐步被唤醒,并开始体现出玩家自己的个体属性来,而这也正是我们所想说的,开发者和玩家两者的共同努力最终赋以了游戏以活的灵魂(共同的呼吸节奏,相互探寻走向和需求,每一次离开都有某种眷念,按照Sean Baron的说法则差不多是这样的:玩家本来可能只是打算稍微体验下游戏消磨时间,可是不知不觉几个小时过去之后才后知后觉地意识到自己正在扮演一个某个游戏角色,并且几乎和这个角色融合到了一起)。

而至于如何将纯粹的理念化归为实际操作,Hidetaka Suehiro(Deadly Premonition,尽管当时这款游戏的骂名居多)将之归结为多个层面:其一是将游戏中的行为与玩家在现实生活中的行为联系起来(在游戏中体现人类的日常需求进而对屏幕外的玩家产生影响,或许还有一些可能某些情节会停留在玩家的脑海不停地徘徊);其二是减少游戏中玩家的受迫感(让玩家在游戏中有自由选择权限而非仅限于任务的强制式);提供给玩家能够区别于其他游戏的印象(比如特征化的角色,经典的对白、游戏角色口头禅或者相对震撼的剧情规划)。Brian Kindregan(StarCraft II)的观点则认为符合逻辑固然是架构故事层面的关键,但是适当和适量的隐秘情节以及一些相应不可预期的游戏机制同样能够挑动玩家对游戏不断的新鲜认知(即所有的环节并不都是能够按照玩家的估算原则走的),吸引人的好故事能够在带入感的感知上演绎出如影视般的视听体验。

当然在可执行的角度上同样存在着如何在操作分寸的可控性,David Jaffe(God of War)认为有些游戏过于着急想展现开发者内心的框架理念,以故事的表现力覆盖了游戏本身必需具备的操作交互属性,诸如在Batman:Arkham City中Bruce Wayne被锁链铐住带往监狱的那段时间就以故事铺垫的名义牺牲了游戏玩法导致玩家在特定的时间内暂时无事可做(如果从游戏的角度而不是影视表现力铺垫的角度,战斗和玩家行为是必须能够尽快获得切换的)。

Ken Levine(Irrational Games)认为这种就必然需要涉及到减少玩家从一个目标向另外一个目标迁移所需要执行的相关步骤(不必像电视台以广告效益考虑所做的剧间强制广告休息,因为玩家在当刻几乎是全神贯注在做一个事情的,没有必要让玩家的思维切换到一个新的事物中,等到差不多时间段内再切回到游戏,这样只能遗失用户对该游戏的专注度)。

另外一种极端就如Erik Wolpaw(Valve Software)所担心的,完全没有必要在游戏中设置一个圆桌任由各种角色围绕期间做各种喋喋不休的高谈阔论(当然没完没了的过场动画也几乎有一样的反面效应)。在国内目前的部分网页游戏中我们是可以这样看的,为了展现战争场面的复杂和壮烈程度,往往对整个战斗需求进行切割(比如同一场战斗又区分为和士兵的战斗、和将领的战斗、和高手的战斗,而每一种类型的兵种可能还可以再区分为若干小种),甚至相似的战斗场面需要经历4至5次以表示足够的繁复(背景相似、声效相似,参与战斗的角色外观上相似,包括数值最后也基本是相似的,这个可以是指多少次技能打击能够击败对手),但是对于玩家而言,这种拖泥带水的表达式则完全违背了开发者设置的初衷而走向反面,我们在舞台剧中所最常看到的一般不是这样呈现的,往往三五个跑腿的小兵即能意指所谓的千军万马而围着舞台简单绕两圈则可能意味着该玩家已经日夜兼程淌过千万重的山山水水了。这里的问题在开发者没有找到合理的思路来处理他们心目中繁复的程式和各种波澜壮阔的画面只能更多借助于重复来进行间接地抒发,以致最终所有的故事模式都有一个基础的模板:来到一个目的地,在这个目的地中参与战斗,征服这个目的地,然后再进入下一个相似的目的地(其实玩家并不完全清楚这些重复的战斗模式对他们能够意味着什么)。所缺少的大概就是Ritesh Khanna(ClipWire)所说的,玩家在游戏中的每一个操作都应该纳入一个具备价值属性的系统,成为一个对后续故事发展有益的筹备,而不仅仅只是一个可有可无的操作指令(或者在当时没能让玩家明白他们操作这一步骤所能够得到的有益价值在后面将呈现为什么)。

有些环节在开发者看来是省时省力且似乎是合情合理的设计,在实际的运作过程中可能会因为出现的高频度而惹恼玩家(玩家在游戏中想体验的并不是一个个只做略微变动的故事内容,他们需要释放更多的故事来满足他们的好奇,而不仅仅只是从换汤不换药的场景换皮),这其中最大的症结仍然是故事叙述不佳,和我们前文所论证的一样,游戏设计的出发点过于自以为是或者过于单薄。Alexis Kennedy(Failbetter Games)认为即便开发者很难从故事框架的角度或者突破,也仍然能够通过以组合的途径或者创造新奇的方式让玩家感受到差异化的体验,诸如在场景中安置一些随机可触发的事件将玩家带入事件模式(哪怕这种事件容量也是单薄的,但终究能够将玩家从寻常的逻辑中岔开,去获得不一样的游戏认知)或者如Vanillaware的Odinsphere将角色与角色之间从剧情层面做串联,在独自完善的同时又给彼此的后续故事留下足够的填补空间或者如Pascal Luban(The Game Design Studio)的建议将影视/小说拓展元素衍化到游戏的表达中(比如使用便捷的方位传送或者自动化传送来改变游戏中冗长到无聊的跑位动作;使用声效特别的变换来唤醒用户对不同环境的辨识)。

而有些游戏事实上也是从相似的角度出发的,诸如Discovery Communications与Hive Medai联合推出的Deadliest Catch: The Social Game(原为获得艾美奖的纪录片连续剧)或者James Patterson以Women’s Murder Club为蓝本推出了Catch a Killer。

篇目2,分享如何创造出优秀的游戏故事

作者:Terence Lee

在本文中,我们将讨论为什么讲故事需要围绕着媒体的互动属性。让我们来学习如何识别优秀的游戏叙述,并理解互动性故事叙述的重要性(而不是像电影中那样的故事叙述)。

想象有一天你突然产生了一个灵感:脑子里突然飘过一个故事,毫无疑问这是人类能够想到的最棒的故事。它具有一个优秀故事的所有元素:一个引人入胜的情节,细致入微的角色以及能够唤起人们回忆的背景设置。

你将如何写一本书去传达这个故事?

首先,让我们着眼于文学媒体是如何运行的。作者写下一些单词去传达想法,并基于某种方式去排列他们而将读者带进故事的世界中。作者会使用描述性语言去唤起读者的感官反应;他们会组织对话去显露个性;他们会将单词组成句子,段落和章节,并掌握适当的节奏。

现在,让我们假设你正在写自己的书,同时忽视了所有的这些指导方针。你使用最普通的描述,匮乏的词汇,并基于一种笨拙的方式去揭示你的角色。这本书的摘录如下:

“这是一个漆黑的暴风雨夜。Bob是一个坏人。他对好人John说道:‘我讨厌你并想要杀了你。’”

你将继续基于这种可怕的风格创造出整本书,你仍会基于某种方式去传达自己脑子里装着一个惊人故事的苍白事实。

阅读这本书的人会嘲笑你。尽管这可能包含一个惊人故事的轮廓,但是它却不能有效地将其转换成文字—-可以说你并未能有效地利用表达媒体(文学)。故事和故事叙述并不相同;你只是在传达你的故事的事实,而不是其吸引人的元素。

让我们列举一个相反的例子,你正在写一本非常棒的书,一直都在创造非常新颖的内容。做得好!而现在你将面临新的任务:你必须以电影的形式去创造你那优秀的故事。

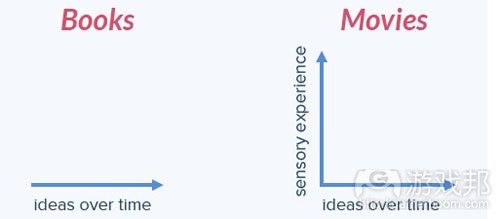

现在,让我们着眼于电影这一媒体。文学是随着时间的发展使用文字去传达理念,而电影则是依赖于添加一种二维的表达方式:感觉输入。

hitbox image(develop-online)

电影的视听体验对于艺术表现形式来说是一种全新可能性领域。书本中的整页描述性语言可以只通过电影中的一个简短影像便清楚地呈现出来。角色间的对话也可以因为彼此的肢体语言,语调以及电影艺术而得到强化。

所以如果要创造你自己的电影,你会怎么做?以下是其中的一种方法:将你那惊人的书籍版本的故事随便递给一个人看,并以电影的形式拍出他们大声朗读的场景。也许你也会设置一些吸引人的风景。这算是电影吧?随着时间的发展它也会通过音频和视觉效果去呈现理念。

尽管始终都包含最新颖的叙述方式,电影却仍是一个失败品。它并未有效地利用表达媒体—-未基于有效的方式使用视觉效果和音频效果去赋予故事生命力。人们会嘲笑它只是尝试着通过彻底忽视电影的整体感官维度去传达一个故事。如果你只是观看一部有个人大声阅读书籍的电影,你还不如自己去看书。

而吸引人的全景画面又怎样呢?它们非常棒,但如果你不能将叙述元素与电影元素统一在一起,所有的这一切只会分散观众的注意力。视觉效果和音频效果是讲述故事的主要工具;它们不能只是被当成媒体的工件。全景画面的电影质量水平需要渗透到整体的故事叙述中;你不能只是将故事和视频分割开来。这就像是尝试着去拯救我们早前所编写的糟糕的书籍一样。你不能只是只是将华丽的电影艺术钉在一本书上并将其称为是电影改编的产物。

当然,这都是再明显不过的内容。让我们假设其实你的电影非常棒。基于该成就,你拥有一个最终的任务:使用一款电子游戏去传达你那惊人的故事。

我们将电影称为一种二维文学方式,第二轴也就是一种感官输入。而电子游戏则引进了第三维:互动性。

hitbox image(develop-online)

在书籍中,深度是源自你所阅读的文字;在电影中,额外的细微差别是源自听到并看到一个场景。而在游戏中,你可以通过进入该场景而发现更有深度的内容。基于互动性,你将能够直接获得故事体验。当你作为游戏主角时,你便有机会去表现出他们的动机和情感。你会通过自己的发现听到并看到某些事,而不是源自摄像师的镜头引导。可以说电子游戏是基于体验去传达叙述体验的深度,而电影则是通过视觉进行传达。

所以为了让你的故事能够适应游戏,你需要做:采用你的故事的电影版本,将其分割成独立的场景,创造一个能够回放片段的计算机程序。你将编写一些有趣的游戏玩法片段,即与故事的一些不是特别重要的部分相关,然后将其设置在电影场景之间。

尽管拥有最棒的故事,最棒的文字内容,最棒的电影式表达方法,游戏却再次不能有效地利用表达媒体—-它并不能将互动性整合到叙述中。你设置的有趣游戏玩法部分又怎样?这就像是将莎士比亚的内容添加到你那糟糕的书籍中,将全景画面添加到你那糟糕的电影中一样,这些游戏玩法并不能推动叙述的发展。你所做的只是将游戏整合到其故事部分和游戏玩法部分。不管游戏玩法部分多有趣,不管故事部分多出色,如果这两部分存在最小的重叠,你便不能说故事成功地通过游戏媒体进行了传达。你所做的一切只是将游戏玩法钉在电影中。

现在,玩这款游戏的人们将会嘲笑它所呈现的叙述多糟糕吧?其实他们并没有这么做。

你也许会惊讶地发现几乎所有基于这种方法呈现叙述的高预算游戏都伴随着最小的重叠内容。

故事vs.故事叙述

等一分钟:实际上这一方法并不是一种糟糕的故事叙述方法。我的意思是,人们喜欢这些游戏不是吗?它们卖的不错,人们也总是在谈论它们的故事有多棒。

是的,我要说的是它具有糟糕的故事叙述,而不是游戏本身多糟糕,或者它们的故事多糟糕。叙述并不是游戏中的一个重要组件,就像它经常会出现在电影或文学中。互动性是游戏的典型功能—-的确,擅长转游戏玩法的游戏经常都是最出色的游戏。然而虽然有许多游戏具有很强的叙述野心,但是它们却是通过将不匹配的电影控制与互动性随便组合在一起去传达故事。

不管你的故事多棒其实一点也不重要。首先真正重要的是你的故事叙述有多出色,这主要是通过你传达故事的媒体形式进行定义,不管是通过书籍,电影还是游戏。上述提到的带有强大叙述野心的游戏虽然拥有很棒的故事,但是它们的故事叙述却非常糟糕。

所以如何才能做到有效的故事叙述呢,并且我们该如何识别糟糕的故事叙述?

关于游戏评论的注释

在我们回答这些问题前,让我们先思考一些问题:这是否全是主观的看法?如果所有人都喜欢它,那又有什么大不了呢?

游戏故事叙述的质量是否是主观的?只有部分是这样。专注于故事的电子游戏与任何创造性表达形式一样,也是一种交流行为。游戏设计师的目标是传达一种体验和主题给玩家。而主观的元素则是预想体验和主题的价值。

然而,非主观元素则是这些理念交流的实效性。大多数关于游戏故事的评论都是在讨论主观的主题,并将主题的清晰性与呈现认为是理所当然的事。这就像是评论家在讨论我们很早之前所创造的一部恐怖电影,并只因为叙述故事内容而给予其积极的评价,忽视了故事其实是以一种糟糕的方式进行呈现的事实。

但人们是喜欢这些游戏的;他们获得了乐趣并喜欢故事。当然我并不是想削减它们的积极体验。相反地,我希望呈现更多出色的体验。我们拥有较低的标准,主要是因为找不到多少真正突出的例子。这主要是基于受欢迎的游戏评论,实际上这只是游戏产业的市场营销的延伸,即确保探索最容易被消化的游戏理念的共生循环。

我们想要的是带有一些互动性的电影,即存在一些完全未被探索过的可能性宇宙。一旦你在思考从理论上来说足够完美的游戏叙述是怎样的时候,你便会意识到我们现在所拥有的还远远不够。我们已经致力于非常接近于这种理想状态的文学和电影,但是我们却还不清楚游戏中的所谓理想状态是怎样的。

本文的目标便是呈现游戏仅仅只是明确了如何呈现一个主题,而我们其实应该先关注于如何是当地使用媒体作为一种表达工具,然后才开始担心呈现内容。

如何衡量艺术价值

在我们谈论故事叙述之前,让我们先谈谈如何识别一款游戏中的突出价值。艺术性或优秀设计的一个强大的指示器是独立元素如何有效地相互协作去传达一个主题。在一部优秀的电影中,所有的内容都应该致力于强化主题理念,不管是颜色还是摄像机角度,还是音乐,表演和化妆等等。如果这些元素中的一个与主题相矛盾,它便会特别醒目并贬低信息的传达能力,或者至少会错失突出信息的机会。

例如在《黑客帝国》中,颜色便用于突出与现实相对立的理念。所有的这些场景是发生在一个模拟矩阵世界中,即带有绿色的道具,衣柜,和灯光,同时所有的场景都是发生在一个带有蓝色色调的寒冷且严酷的现实世界中。这一视觉提示能够帮助观众从潜意识中区分这两个对立世界。这是强化游戏主题的一种有效方式。

如果只是任意地选择调色板,那么相对立的现实这一主题将会被削弱,从而变得不再那么明朗。一个优秀的电影摄影技师将会为了强化理念的优势而找到并使用这些机遇。同样地,在游戏故事叙述中,我们也会发现机遇去强化带有像互动和决策制定等游戏元素的故事信息。如果你在设计这些元素的同时忽视了主题,你便只能呈现出一个较糟糕的故事叙述体验。这是关于我们早前揭露的内容的重述,即我们必须利用媒体的特性才能有效地在媒体中传达一个故事。

基于这样的态度的创造性作品将更突出且相一致,因为它努力传达了许多带有少数组件的相关理念。而较不协调的游戏则会让人觉得不够集中,太过笨拙且自相矛盾。如果你想要识别出糟糕的故事叙述,这便是你需要寻找的属性,即我们可以通过玩游戏并关注于脑子里是否充斥着这种不一致性将其检测出来。

三种类型的失调

认知失调—-这是一种内部的心理冲突,通常都很细微。当你的脑袋里同时拥有两个冲突的理念时,这些情况便会出现。当我们在玩这类游戏时会感受到怎样的失调呢?以下是我所明确的3种类型。

相矛盾的体验

第一种也是最显著的一种便是ludonarrative失调(游戏邦注:ludonarrative是由原LucasArts创意总监Clint Hocking提出,这是一个合成词,由ludology和narrative两个单词组成,意指游戏故事与玩法之间的冲突)。这意味着什么?ludonarrative失调是发生在你看到英雄正哀悼着与家人的疏远,而下一刻,你却驾车碾过100个人。Ludonarrative失调是发生在一个勇士的同盟独自说着自己多狡猾多可怕,但在下一刻他却愚蠢地绕着圈子旋转,烦人地阻挡着你的前进道路,然后中弹死掉。即当故事所传达的与玩家所做的或体验不相符时便会产生这种情况。

这种类型的失调经常发生在你分离了叙述与游戏玩法时,因为叙述在某一时刻是由作者所决定的,接下来才是玩家。这让我们很难正视故事在说些什么,因为它与我们所体验的内容相矛盾了。

“我是谁?”

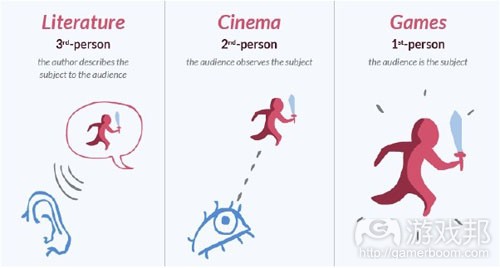

下一种失调便是身份失调。为了解释这点,让我们先回到将文学,电影和游戏作为一种维度的类比。着眼于这三个内容的另外一种方法便是通过它们之间越来越接近的视角。想想书籍:许多文学内容可以被描述成第三人称故事叙述:它将通过第三人称(也就是作者)的视角以口头叙述的方式向你传达某些事件,你将按照自己的方式去理解这些内容。

另一方面,电影基于第二称的故事叙述方式:你将看到事件在你的眼前展开,直接看到事情的发展。最后,电子游戏是基于一种第一人称故事叙述方式:你是住在故事中的演员。比起只是听着故事的发展或看着发生了什么,你将直接体验它!

hitbox image(from develop-online)

然而,基于糟糕的游戏故事叙述,我们经常在身份上出现巨大的失调。在某一时刻,你是主角,正在探索世界并与敌人打斗。而在下一时刻,你将跳离原来的身体并看着角色不受你的控制与别人进行互动,独自行走并交谈。

在这种情况下你已经从第一人称转变成第二人称了。你到底是谁呢?你是演员还是观众?游戏是否应该与你的视角相协调。如果你一直有游戏不信任你的感觉,这将会大大削弱你的行动的重要性。

协作的一个基本原则便是去呈现,而不是讲述。如果你想要传达角色很敏捷的信息,不要明确地说“Bob非常敏捷”,而是应该将其呈现出来:“Bob躲避了掉落的巨石。”而在游戏中,你应该去落实行动,而不只是呈现。不要只是呈现你的角色躲避掉落的巨石的画面,应该去落实它:让玩家亲自去躲避巨石。如此玩家自己便能够亲自感受到这种敏捷,而不是他的角色。这种将角色的开发转变成个人开发便是在游戏中创造沉浸式故事叙述的重要方法。

过场动画的问题

最后的一种失调是奇怪的模式转变,即发生在每次游戏尝试着在“叙述模式”与“游戏模式”间转变时。这一分钟你正在玩游戏,而下一分钟你则在看电影。这将打破沉浸感,不断地提醒玩家你正在消耗一件媒体。不止如此,这也会剥夺玩家在游戏过程中所建立起来的紧张感和其它情感。

想想你正在玩一款让人紧张的游戏,在此你将为了活命而战斗。你处在一个非常艰难的部分:你需要一直保持着警觉并留心于自己的每一步前进,确保你不会犯任何错误。你所拥有的压力和紧张感都很真实:这是一种切实的压力,而不只是因为你的角色处在一个子弹满天飞,僵尸乱窜的情境中,还因为你自己也面对着这种挑战,即尝试着去精通游戏玩法并走出这一艰难的情境。这部分便是一种优秀的故事叙述:玩家所感受到的情感与他们所面对的主题情境是相匹配的。

当你正在玩这部分游戏时,突然地,画面将被拉远,现在你所面对的将是过场动画。突然间,你的所有紧张感都消失了。你放下了控制器并放松下来,只是看着屏幕。尽管现在屏幕上的角色忙于一些更紧张的情境,从直升机上跳落等等,作为玩家的你却不再那么在乎这一切了。在内心深处,你知道这只是一种“电影模式”:现在所发生的一切就只是这么发生着;这都只是“故事的一部分”。

你之前在游戏模式中所犯的任何问题都很重要:它们会给你带来现实世界的压力。但现在,因为你不再进行控制,所以你看到角色在电影模式中所犯的任何问题都只是“计划中的一部分。”你不再属于游戏世界。你会发现当转变到这一模式时,自己会大大放松下来。现在游戏中最紧张的部分对于你来说也只是放松肌肉并深深地吸口气。游戏以变得更加“电影化”为名义牺牲了好不容易才创造出的玩家情感。

每当游戏在游戏模式与电影模式间转换时,你对于玩家角色的依附将从100%的情感投入转向100%的情感分离。这真的是一种非常不和谐的失调。

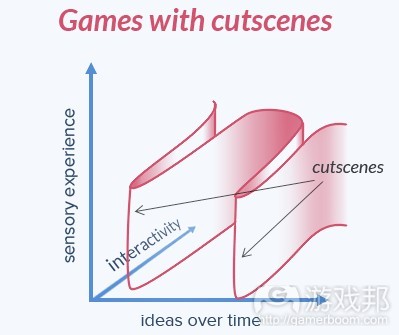

以下是关于这种模式转变的另外一个不同例子,这是发生在游戏外部:无声电影。这些电影具有非常棒的电影艺术和非常出色的表演。你可以说它们填满了视觉体验。但是有时候却会出现幕间标题。

幕间标题是指那些用于描述发生了什么或包含对话的全屏字幕。在这些字幕间,电影退回了一维中—-它忽视了感觉经验,即区别电影与文学的独特元素,并直接将文学呈现在屏幕上。如果你将在我们的2D图表上表现出无声电影的进程,它便是如下的效果:

基于电影的长度,它通常将维持高水平的视觉体验;然而,不管何时会出现幕间标题,感觉经验的数量都会下降至0左右。同样的情况也发生在游戏过场动画中。

hitbox image(from develop-online)

当过场动画出现时,你忽视了整体的互动性维度,即游戏突显于电影的元素,并直接将电影呈现在屏幕上。带有过场动画的游戏就像是无声电影版的游戏。至少无声电影免除了其技术上的限制—-而游戏却不存在类似的借口。最糟糕的部分在于在过场动画期间会出现最重要的情节点,同时让你不能亲自参与其中。

让我们着眼于过场动画的一个反例。《半条命》系列具有一个变换方法:比起呈现一部电影,它们在游戏玩法期间自然地打开了场景内容,你也从来不会失去对角色的控制。角色开始在你周边讲话,你眼前会出现让人印象深刻的画面,但这过程中你始终把握着控制权。虽然在这期间你将被限制于一个闸口区域,但你仍然能够四处走动并观察事物,在控制角色的同时观看一些行动的变化。

这真的很有效:沉浸感并未被打破,你并未改变视角,并且从未停止作为故事中的一名演员而直接体验各种情况。尽管这并不是那么完美:公式最终是可以预测的,一旦你开始意识到‘好吧,我现在其实是在一个故事房间里,’,幻觉将逐渐消失,但从很大程度上来看它还是很有效的,至少比过场动画好。

明确的故事和玩家故事

我们已经谈论了许多有关游戏在哪些方面做错的内容。那么我们该如何完善自己的故事叙述呢?首先让我们更深入地着眼于叙述本身的理念。

什么是叙述?是否所有游戏都具有叙述?是否所有游戏都需要叙述?让我们做出一些定义。首先,游戏中有两种类型的叙述:第一种便是传统类型,即当我们在谈论情节,角色和对话时所想到的;第二种则是玩家个人体验的叙述。

第一种叙述是我所谓的明确的故事。这是关于游戏的内容。游戏是关于打败僵尸。游戏是关于探索世界并拯救公主。游戏是关于从外星人手中拯救世界。这是游戏的美学环境,主要是通过视觉,声音和文字进行传达。并不是所有游戏都带有这种类型的叙述,但却是大部分游戏都有。RPG,冒险游戏和行动游戏通常都会特别强调明确的故事。也有些游戏会完全避开它,如许多益智游戏和大多数传统的纸牌游戏。甚至像象棋等游戏也具有少量的这一元素:被当成是一种中世纪战争游戏。

第二种类型的叙述便是我所谓的玩家故事。这是玩家的个人体验。当玩家在玩游戏时,他们的脑子里会想很多事:他们会经历各种情感,他们会对角色和事件产生认知,他们会与自己的行动和屏幕上的结果产生彼此间的关系。这些都能够创造一个不同类型的叙述体验,即带有它自己的节奏,角色,情节和对话,并且区别于明确的故事的内容。

这些玩家故事是否是真的故事?是的,实际上,玩家总是会完全将这些故事告诉别人。询问别人他们在《俄罗斯方块》中的紧张比赛。

“我一直在尝试着打败好友的高分。我有一个很棒的开始,但在快到最后的时候我却老是得不到竖直组块。这决定着最后几行的消除,最终我得到了一个!我使用它清除了许多组块,并打败了好友的高分。”

这是一个真实的故事。也许从文字上看这并不是多么激动人心,但是在玩家心中,这却是伴随着真正的冲突,高潮和结果的完整的体验。因为这是玩家直接经历到的,所以他们会有更深刻的感受。

所有的游戏都有这种类型的叙述。甚至是像足球这样的游戏也有其自己的故事—-人们一直在告诉你某些内容,重述着激动人心的比赛。许多游戏同时具有这两种叙述,即明确的故事和玩家故事。

然而,一个优秀的玩家故事总是最终结果,而一个明确故事的角色总是应该支持一个优秀玩家故事的发展。带有惊人的明确故事和可怕的玩家故事的游戏就像是我们早期创造的带有优秀情节,但却不能有效传达它的书籍一样;这是我们基于糟糕的叙述和无聊的视觉效果所创造的电影。你不能只是分开设计两种故事:就像我们之前所看到的,将有趣的游戏玩法区分于明确的故事将产生失调,这意味着你最终将看到一个脱节且糟糕的玩家故事。

统一两种叙述

所以我们该如何一起讲述一个优秀的玩家故事和优秀的明确故事?掌握这一点:最出色的游戏故事叙述是出现在明确的故事与玩家故事完整地融合在一起时。

当你在玩游戏时,你应该永远都不需要问自己:“我本应该做什么?”在一款优秀的游戏中,你应该做的事将与你想要做的事相贯穿。如果你在玩游戏的时候所获得的情感和动机非常符合游戏环境,那么便会发生一些非常惊人的事情。

以下是来自第一款《传送门》的例子。在这款游戏中,你是作为一个配有一把传送门手枪的测试对象,尝试着经历不同的试验室。快到最后的时候,你乘坐上一个缓慢移动的平台到达一个所谓的将你你之前良好的测试表现的地方。突然,你发现这个平台其实是要将你置于死地。

当我在经历这一场景时,我非常恐慌:这时候我完全专注于游戏中,之前我觉得自己能够解决这个谜题,并准备获得奖励,但是现在我却被出卖了。无意识地,我的眼睛引导着我朝一个最理想的界面开枪,我为自己创造了一个出口,并逃离了鬼门关。等一下,我好像打破了系统。我利用自己的智慧超越了敌人。

当然了,最终证明我应该这么做。但是当我如此行动时,这完全是基于我为了实现自我保护的动机,而不是因为我想要“推动故事的发展”。观看角色侥幸逃脱与利用自己的聪明才智亲自进行体验是白天与黑夜的区别。主要的情节元素将自然地发展,而未出现任何失调。我想要做的以及我应该做的都是一样的。

游戏之前部分的所有内容都是为了让这一场景能够自然地呈现在玩家面前:在传送门机制中的培训;预示着厄运的机智的对话;让你想要逃脱的试验室格式;关于逃脱具有可能性的小小暗示。

让我们将这一场景分解成两种叙述类型:玩家故事是关于你使用智慧逃脱一个让人紧张的情境。明确的故事是关于你的角色Chell使用她的智慧逃脱一个让人紧张的情境。它们是完全相同的内容!

让我们将这一场景与一款不同的游戏中的类似场景相比较。我将使用全新的《古墓丽影》为例,尽管在其它游戏中还有无数情境是基于同样的方式去表达。在一个场景中,你正观看者角色逃离危险的一个过场动画,突然一颗巨石将砸向你。你具有一个选择:在接下来的半秒内按压X按键。如果你这么做,你的角色将安全地存活下来。而其它行动将导致你的角色死去。

不管是《传送门》还是《古墓丽影》的场景似乎都具有同样程度的危险:在这两种情况下,四百意味着你的英雄将会死去。然而在《古墓丽影》中,是由玩家去体验这些的情境。也许当你看到可怕的死亡动画时会畏缩,或者当你在前面几次未能即时按压按键时会感到受挫。但却没有什么比使用你自己的智慧让自己脱险更让人激动的了,在《传送门》中也是如此。

尽管《古墓丽影》的场景更像电影,并且具有让人印象深刻的视觉效果,但这却是很容易让人忘记的。而你差点就要死了,这点不应该更让人难忘吗?!但事实却不是如此,因为玩家故事与明确故事是相矛盾的。在这里,玩家故事是指你观看一个过场动画,突然游戏基于一个明显但却让人厌烦的方式要求你按压一个按键,你将被迫在无聊的重复折腾下按压这个按键。而明确的故事是指你的角色Lara Croft使用她那敏锐的感觉和技巧逃离了危险。这两个故事具有显著的差别!它们是如此的不协调啊!

这是我在说明确的故事是玩家故事的美学环境时想要传达的意思。这是构造你的行动和动机的一种方法,这是增强一致性并强化主题的方法。这两种叙述类型能够相互合作。如果在《传送门》场景中没有明确的故事,你将只是从灰色的盒子跳进灰色的墙中,如此你便不会进入一个可以重置你的位置的红色区域。你可能会喜欢识别谜题,或享受于精通机制,但你不会觉得自己“在打败系统”,或者在使用智慧去避免死亡。

另一方面,如果不存在玩家故事,就像你只是观看某些情境的电影画面,你也不会感受到这些。你可能会因为某些视觉效果而兴奋,或者因为主角的存活而高兴,但你肯定不会感受到任何个人的成就或冒险。

线性,脚本和电影故事

所以我们只是看到一些关于较短的行动序列的优秀故事的例子而已。那么我们该如何将这些原则延伸到一个完整的游戏故事呢?

这很难。很少有游戏能够成功做到这点,特别是带有线性,脚本和电影格式的游戏。基于这种格式,我所说的是那些特别强调明确的故事,带有基于脚本的事件,角色和对话,以及明确的结局的游戏。这种格式具有许多缺陷:缺少选择;过分强调对话,玩家缺少对它的控制;具有刻板的线性进程。在电影中,这些特征并不是什么缺陷,但是在游戏中,它们将与该媒体对于互动性的强调产生矛盾。

《传送门》便属于这类型游戏,但是它却在努力地做到有效的故事叙述。我认为它是一个例外,即具有独特的能力能够利用这些缺陷。缺少选择,片面的对话以及线性进程等等缺陷在《传送门》的试验室中都是行得通的。你被迫做游戏告诉你的事,因为你只是一只被试验的天竺鼠;你不能回话,因为除了一个非实体计算机外这里没有其它角色;在这些试验室中你只有一个前进方向。

这种便利的格式意味着很少会出现失调。但是你不能将这些技巧普及到其它游戏中。这就好像克服这些缺陷的唯一方法是将其整合到故事本身中。这并不是大多数游戏故事的选择。

也许线性,脚本,电影故事只是不是游戏的最佳格式。有些带有这些故事的游戏表现的很好,至少在某些方面是这样的,但我不相信我们能够长时间地看到这些优势。这是改编自电影的不完美的风格,它只是不是那么适合有关互动性,选择和个人体验的媒体。

我不认为它应该作为游戏故事的转向格式。还有其它格式吗?当然还存在一些选择,它们中的许多都是基于实验性,但有一个是我特别想在本文中与你们分享的,那便是意外的叙述。

将玩家放回控制中

我们发现基于线性,脚本和电影格式的缺陷都是以控制为中心。作者们想要创造一连串能够恒久开启的具体事件,但如果松开了这样的欲望会怎样呢?如果我们放弃严格的控制会怎样?在这些游戏中我们经常看到的便是,它们先创造一个明确的故事,然后围绕着该故事去设计玩家故事。它们都拥有既定的脚本,然后基于该脚本去创造游戏玩法,并尝试着让它们相匹配。如果我们做的刚好相反会怎样?如果我们先设计玩家故事,然后在创造明确的故事去匹配玩家故事又会怎样?

现在,我并不是想要先创造一个有趣的抽象游戏,然后编写一个有意义的脚本故事。这当然是一个值得尝试的好方法,但这却不是我们现在要说的。我的意思是,比起拥有任何基于脚本的元素,我们应该让明确的故事去描述玩家故事。我们应该情节,高潮和角色都是源自玩家的体验。总而言之,故事应该描述玩家所做的,而不是玩家需要做的。

以下是一些例子。

《旅途》

第一个例子便是《旅途》。在这款游戏中,明确的故事非常散漫。当你开始时,你所知道的一切便是自己是沙漠中某种人或生物。就只有这样而已。这里没有明确的目标,动机,情节,冲突或对话。然而,这些内容却能通过游戏设计非常自然地出现。

在较早的时候,你会看到远处的山上闪烁着一道光束。可能是有意识或潜意识地,你的目标便变成是到达那座山,因为它似乎始终都存在于你的视线中。在行进的途中,你将遭遇一些角色。他们是其他人类玩家,正与你经历着同样的事。你不能通过语言与之交谈,但是你却可以使用肢体语言和歌唱能力进行传达。

这时候,每个人所看到的故事是不同的。有些人选择与充满好奇的新玩家结伴而行,一起解决问题,构建友谊的桥梁,并携手走到最后。也有些人与其他玩家发生矛盾,选择独自前进。还有些人虽然交到了朋友,但却前进过程中与朋友分道扬镳,同时还哀悼着失去朋友。甚至有些人找到了引导者,即那些能够告诉他们如何前进的资深玩家。

这些都是对玩家来说非常有意义的优秀故事,因为这是他们为自己创造的个人体验。它们不只是像紧张的《俄罗斯方块》游戏那样的个人体验,同时也是像优秀的电影那样带有情感的复杂体验。让我们想象:

你独自一人待在一个荒原中,然后你掉进了悬崖深处。你不知道如何逃出去,然后从某个地方出现了一个陌生人向你伸出了援助之手。你们两人便成为了好朋友,携手探索这个世界。然后当你顶着大风穿越一座桥时,你的朋友却掉下去了!

你呼喊着他的名字,希望他能听到。你瞬间充满了绝望,觉得自己再也见不到他了,但突然间你听到遥远的地方传来了他微弱的哭泣声。你知道这个声音,你之前听过这个节奏。最后,你想办法下去将其拯救出来,就像他之前拯救你那样。最终你们能够安全第携手走到旅途的最后。

这就像是电影一样!然而,这里的体验比电影更强,因为你能够亲身经历它。这种体验并不是作者事先决定好的,而是基于你和新朋友的行动所决定的。你们将组建真实的朋友关系,感受到真实的情感,绝望与乐趣。体验的脚本版本只能引出同感;而不可能是直接的感受。你可以将其称为一种文字叙述,因为所有重要的一切是发生在真实的生活中,缺少实体体验将只会陷进一个神秘的荒原中。

并不是说设计师未能设计出任何明确的故事。相反地,比起尝试想出最特别的情感线,角色,对话和事件,它们选择设计一个能够突出这些元素的环境。

当你找到另外一个玩家时,这里存在一些视觉线索将强调他们的存在与出现。当你通过唱歌和肢体语言与之交流时,你脑子里便会浮现出所有有关其他玩家个性的图像(这便是一种角色发展!)。当你们能够和睦相处时,将会出现一次大危险去测试你们的关系。这便是一个优秀故事的所有元素,它们是由设计师精心设计的。它们并不会一下子震慑到你,而是会自然地出现。

《矮人要塞》

让我们着眼于另一个例子。我们谈论的是让故事出现在玩家的体验中;这款游戏便将这一理念带到了一个全新的水平:《矮人要塞》。

我们很难去描述《矮人要塞》,但总的说来,这是一个对于矮人王国的详细模拟游戏。从图像看来它非常简单,但不要因此被骗了:这款游戏真的非常强调细节。它模拟了各种内容,包括几千年来河流穿越峡谷,孩子的睫毛刷掉落下雨滴等等。这是一款沙盒游戏,你尝试着创建自己的王国,直至大灾难突然降临,并卷走了一切。

关于游戏很棒的一点便是其画面的简单性让你能够利用想象去填补空白,并为游戏添加详细的意义与动机。这就像是当你在阅读一本优秀的书籍时,你的脑子里将想象着角色的外观和声音。通过这些以及游戏的复杂性,你便能够想象会出现什么类型的故事。DFstories.com便编入了许多这样的内容:有些充满了行动,有些意外的真诚且感人,有些则非常平庸。通过检测去看看人们在玩这款游戏时脑子里会产生怎样的想象与情感。

尽管我认为《矮人要塞》是这类型故事叙述的极端面,即对于大多数人来说这是很难做到的,但是从这款游戏中我们还是能够学到许多。我们可以学到的主要内容便是一种意外情境——不管它是源自复杂规则的互动,玩家的试验还是只是通过随机的机会,这都会对处于脚本情境的玩家产生影响。

当情境具有目的性并添加深度到玩家故事时,美好的东西便会出现。实际上,一个意外的情境便意味着它可能是独特的,将会让玩家拥有特别的体验,因为它们知道之前每人遭遇过它。这就像是当你一开始在玩《我的世界》并找到一个美丽的自然构成时的情况。你会充满敬畏感,知道你是第一个看到这个的人。这是具有开拓性的发现。这是基于脚本情境很难创造的感受!

《Brogue》

最后一个意外叙述的例子便是一款名为《Brogue》的roguelike游戏。

在《Brogue》中,你是一个冒险家,将探索一个程序生成的煽动,并尝试着触及最底端的人工制品,并将其带回地面。这真的非常困难:死亡是经常会发生的情况,你总是会犯各种错误。这里拥有较小的明确故事:你所直到的便只有你在寻找什么以及身边的世界非常危险。与《矮人要塞》一样,最低水平的视觉效果让玩家能够形成他们自己对于行动的看法。

然而,游戏中具有许多机会能够填满优秀玩家故事的意外性。在道具,敌人和环境间存在许多复杂的互动性,你总是有许多选择能够处理这些当前的情境。草着火了;敌人变成了同盟;掉落的道具将触动开关等等。在个体元素间存在着许多互动,然而这里并不存在脚本序列。从中会出现什么类型的意外故事呢?我曾看到自己的朋友是这么玩游戏的:

他陷在了一个很深的峡谷上的一座木桥上,地精封锁了两端的出入口,阻碍了桥的通行。他的生命值变得很低,不能与之相抗衡。他只拥有一个不明的药剂,如果这是一个能够让人悬浮的药剂,他便可以安全地离开这座桥。在离树精几步之遥的时候,他喝下了药剂。但不幸的是,这却是一个焚化药剂!

一个巨大的火焰喷射了出来,环绕着他和地精,桥着火了。瞬间桥被烧毁,所有的人都掉到了悬崖下。幸运的是他安全掉到了水里,从而帮助他扑灭了身上的火。有些地精活了下来,也有些掉到了地上死了。然而一个满身是火的地精掉在了充满爆炸气流的找找中,并触发了大爆炸而消灭了剩下的地精。我的朋友逃脱了,并继续深入洞穴进行探险。

这一场景中充斥着行动。这与任何行动电影或游戏电影一样激动人心,但这只是我在这款游戏中看到的许多惊人场景中的一个。尽管如此,所有的这些都不是基于脚本内容;这甚至不是设计师有意的设定。这只是源自机制的互动所产生的情况。《Brogue》的难度进程意味着当你越深入游戏中,你便会遭遇更多元素,并意味着诸如此类的更多互动与紧张序列会出现在你眼前。

《Brogue》的游戏过程的确包含了一个非常棒的故事:玩家在危险的洞穴中探险的故事。只是因为没有名字,对话或电影画面并不能否定它的故事。我真的认为《Brogue》的故事叙述超越了像新的《古墓丽影》这样的游戏的故事叙述(尽管游戏完全未受到情节作者的影响)。

是的,《古墓丽影》具有更复杂的情节和更细致的角色,但我们需要记得:故事与故事叙述并不相同。也许比起《Brogue》,《古墓丽影》能够用于创造出更棒的电影,但我们现在谈论的是游戏。《古墓丽影》就像是我们在文章的一开始所提到的具有优秀故事的书籍,但却不能有效第使用文字和句子。而《Brogue》更像是海明威的作品,带有简单的情节,简单的语法和简单的句子结构,但却非常擅于协作,能够有效地传达内容在护体。我认为行动和冒险的主题能够更深刻地与《Brogue》达成共鸣,而不是《古墓丽影》。

新境界

意外叙述仍然是我们未做出较多探索的新技巧,但是我认为它具有非常大的发展前途,因为它能够塑造出很棒的个人体验。这是许多可行的故事叙述方法中的一种,我想如果我们想要寻找完美的游戏叙述形式的话,我们就需要深入这些领域。直到那时,让我们记得在创建一个明确故事的同时专注于玩家故事。

电子游戏是一个创造性表达的年轻媒体。书籍已经诞生一千多年了,而电影也出现一个多世纪。但电子游戏却是在几十年前开始流行起来。我们刚刚经过游戏的无声电影时代。我不认为我们已经完全理解了在游戏中创造优秀叙述的意义,所以我们需要开放思想去看待不同的故事叙述格式。

我们应该停止将电影当成是叙述的灵感,并开始意识到比起最大的脚本和电影游戏,非传统的结构能够作为更强大的故事技巧。让我们重新定义游戏叙述,使其不再只是关于情节和对话——我们真正在乎的应该是发生在玩家脑子里的故事。

篇目3,《Bastion》是如何将叙事与玩法完美融合?

作者:Andrei Filote

叙事与电子游戏总是紧紧相扣。即使《Pong》这种简单游戏也会通过某种方式展现故事,比如玩家基于画面内容创建自己的体验。通常游戏中的故事是通过玩家与之互动产生,但甚至在这种媒介诞生数十年的时间后,我们仍旧无法确定制作互动式叙事风格的最佳方式。

数十年来,相关学者与设计师已经就此方面进行了详尽探讨,但现在,我们有必要看看那些能够体现玩法与叙事完美结合(个人观点)的典范。

电子游戏是如何催生出故事?其实这得归结为大脑消化信息的方式。根据我们处理视觉信息的方式,图像会自动转变为叙事模式。许多游戏均按此方式呈现故事,因为同电影一样,游戏也指一系列按一定顺序发展的图片。重点是,我们常把叙事、对话、故事与玩法隔开,但事实上,它们如同硬币的两面,紧密相连,相互依存。由于电子游戏的背景是个虚拟环境,因此我们对该环境与其中事件的认知会自动形成故事。

如今,许多游戏一方面让玩家经历事先安排好的故事情节,另一方面则通过他们与虚拟环境的一系列互动,自然而然地引申出更多故事。但总存在一系列限制条件(无论是技术上,还是哲学上)隔离这两方面,因此我们常以交替方式进行体验。这也引出一些问题:我们从未在游戏中设置适当的故事情节;而在玩法或过场动画中产生的故事则与游戏毫无关联。因此,整个体验形成一种断裂模式:一部分是游戏,另一部分则是游戏中包含的电影。

尽管存在这些常见问题,但仍有些游戏致力于解决非互动式过场动画的约束条件。其中一例便是最新作品《Bastion》。

互动式故事:三个方面

以下三个事例均强调了提示信息的用法,这是一种尤其适合电子游戏但却总被忽略的技术。在游戏这种重视爆炸性元素的媒介中使用如此低调的元素,似乎是一个愚蠢做法,但电子游戏对关注度的需求本性,却正是提示信息能够发挥作用的重要原因。当你正陷入一场苦战时,突然呈现的一些截然不同的内容,或许有可能创造一种长远动机,为一些明显的操作行为提供全新的情境。

1.暴力折射叙事

通常,暴力是游戏的导火索,但当用户在消灭对手上倾尽大部分时间后,战斗将变得无关紧要,故事情节也失去本身意义。《Bastion》提示的潜在信息则改变了这一情况。

首先是游戏中存在的大量武器。武器科技的不断提升透露出Caelondia社会日益突显的战争。与此同时,我们也见识到了一个需要层次:创建(锤子),对抗环境(矛、弓),控制环境(火箱),对抗其它社会(卡宾枪、步枪),完全主宰那些社会(迫击炮、破坏性炮弹),解锁终极武器(摧毁)。

游戏进程紧随故事与主题发展。随着武器具有更大破坏力,你越发认识到,由试图主宰自然的殖民者成立的City,与仍生活在不受侵犯神圣领地的Ura创立的社会之间存在种种冲突。

显然,这是一段社会暴行的简史。随着殖民者开拓新大陆,他们会销售锤子,换取弓箭、步枪、大炮。Calamity割裂山脉,摧毁生物的能力其实是种超现实的核武器。同时也是武器中的极端,并且是人们不会打败战的终极保障。游戏发生于Calamity的背景之下,如果要扭转局势 ,Kid除了与现实妥协之外,别无选择。他想逃脱的同时,也在为其所困。

2.情境化的敌人

你在游戏中面对的敌人既不是无名氏,也不会毫无作战动机。在Calamity发生之前,它们扮演着不同角色,现在则开始重塑身份。根据叙事者的说法,它们会与Kid发生冲突,后者的目标是重建Bastion,争取全面胜利。无论叙事者的措辞是否可信,但这并不能构成屠杀那些只是试图建立自己的安乐天堂的无辜物种的理由。

游戏让你意识到,敌人拥有与自己同等的生存权利,这是该游戏的一个关键部分。这些敌人也是目前Kid最显眼的反对势力,它们挣扎在组织、重组与重建的过程中,试图建立一个劫后重生的世界。这明显是一个有得有失的过程。比如Windbags本来是种较低的社会阶层,现在则无家可归迁移至一个荒废城市;Ura幸存者将悲痛转化为复仇力量,但从未忘记尊严;Peckers则在灾难后充满了优越感,他的愤怒方式十分有趣。人人都会按照自己的动机清晰行事,而且乐意利用自个资源完成目标。它们的做法仅仅是折射出Kid的行动,并且与之一样充满决心。

Bastion中的对手本质并不恶劣。它们也不会盲目接受厄运。大多数时候,它们属于自然世界,或社会的一小部分,或是一个完全不同的社会。可是,它们均遭遇侵略者(你)的暴行。这是一个了不起的成就,因为《Bastion》并不只是简单地涌现众多敌人让玩家扫射,它也阐述了敌人的立场,这一点让游戏蕴含更多深意。

Bastion(from gamecareerguide)

3.神殿

神殿概念完美结合了两种需求:一是用于解释Caelondian人的信仰,二是发挥增加游戏难度的功能。而这些用途则通过祈祷来实现。祷告本身存在两个层面。首先是界面上,借此玩家能够知晓自己陷入的麻烦(游戏邦注:比如敌人的攻击加快加强等)。但故事模式不存在界面,从Kid角度看也不存在所谓的用户:他的祈祷行为纯粹是种信仰,如同摇摆锤子只是种习惯。他决定进入未知世界,进行相关探索。

他想要什么?我们不得而知。我们只知道自己会面临困境、考验与磨难,这些都是惩罚形式。现在猜测Kid会因过去行径遭遇惩罚是否为时过早?我们只能疑惑,但疑惑本身就是奖励与成就——我们已经构造出拥有自己生活与体验的角色,它们同我们一样存活于每时每刻,就好像它们已经自成一体,存在于只有我们有权接触的时空。而这正是所有叙事内容的目标,无论是游戏、电影或小说。

我们只有通过提示信息才能感受到这一点,我们很容易忽略这些静谧和轻声诉说的内容,但它们却为我们留下了无限的想象空间。由此我们可窥见其美丽的外表下,多彩的世界背后,玩家所触及的壮丽物质世界之外的深层意义——《Bastion》是一款关于种族冲突,甚至是种族灭绝,以及关于人类种种错误的游戏。

Bastion(from gamecareerguide)

特殊元素:叙述者

不少电子游戏均采用叙述者支持故事情节的发展,但《Bastion》中的叙述者却显得十分独特,它贯穿故事始终,并且会回应玩家的行动。

由于《Bastion》的叙述者会根据玩家动作做出相关反应,因此Supergiant Games开发团队需要确保他的每句台词均吻合游戏情境,玩家的动作氛围以及游戏叙事内容。因为稍微一丁点儿偏差,或某个错误步调,便会致使这位忧郁严肃的叙述者陷入滑稽境地。但《Bastion》并没有犯下这种过失,其叙述者努力配合脚本情节与玩家自然催生的故事。

虽然在与玩家配合上耗费了大量时间,但该作的叙事内容不仅限于描述玩家的行动。玩家在整个游戏过程中,不仅能够获得清楚的阐述内容,还会发现自己与叙述者的配合更为紧密,因为后者的每句台词均透露出他自己与游戏世界浑然一体的感觉。

同时,我们很容易发现这整个设置是开发者精心构造而成,它除了营销推广之外并无其他有趣用途。我们可以想象这个系统的多种不同形式,甚至是一个允许玩家停用整个叙事模式的系统。但《Bastion》并不能这样做。如果根除该作的叙述者,这便是削弱游戏的主心骨,移除了游戏中的所有有意义的行动。这并不是与其他系统(例如武器、升级等)平行的系统,而是承载整个故事叙事框架的系统,它是《Bastion》体验的核心。

同神殿一样,叙述者的作用也具有多种层面。他可以在游戏进程中为我们揭示游戏世界的情况,但他并不是无所不知的全能者,仅仅是利用自己获知的某些信息提示玩家,时而回忆,时而揣摩与猜测,有时候甚至是一无所知。例如在游戏最后阶段,他在游戏叙事框架中只告知我们要去取悦两个人物,而我们最终与无时不刻相伴左右的叙述者面对面时才得知情况,才知道只有采取这一行动才能等到游戏的“结局”。

而在游戏尾声,一切都已发生改变。玩家在通关后无法回头。有些事情已经永远逝去,这不仅包括选择的权利,还有其中的幻觉。其故事清楚表明,强大的记忆和推测能力有助于玩家方便快捷地重建家园。我们从能够简单修饰的过去,进入了未知的现在。我们抵达了故事源头、结局与Bastion的核心部分。接着,故事终结,叙述者褪尽神性,真实世界迎面而来。

篇目4,游戏中的故事叙述所面对的3大问题

作者:Tielman Cheaney

如今电子游戏中的最佳故事在面对书籍,电影和戏剧中的故事时只能说是影子般的存在。为什么呢?

游戏包含了巨大且不可避免的障碍,会阻碍传统的故事叙述。

以下是游戏故事所面对的三大问题:

1.系统问题

系统创造了游戏乐趣,但对于其它媒体来说却是无聊的存在。玩家喜欢学习,游戏并精通系统。

游戏是如何使用系统:

游戏会花费时间去记录每一步并在双方交战时重新加载士兵的步骤。没有一部电影会这么做。复杂的战斗系统会使内容变得有趣。管理弹药,衡量前进的风险,使用遮盖物,然后发射子弹并射中敌人等等都是有趣的。如果不能有效使用系统便会造成暂时撤回。枪战是战斗游戏的乐趣元素之一。“闪光雷击中地堡派的人的时间是否足以让我朝坦克发射两枚火箭弹?”

电影是如何使用系统:

但是在电影中,枪战只有在我们与角色产生情感共鸣后才会有趣。在《现代启示录》,《黑鹰降落》,《拆弹部队》,《全金属外壳》等等战争电影中,呐喊与射击出现的时间还不到片长的一半。电影的乐趣主要来自角色的互动性。“Jeff是个可靠的士兵,但他却疯了。他是否能在下一次突袭中杀掉所有人?”

书籍更不会侧重行动,就像《丧钟为谁而鸣》,《杀手天使》,《红色英勇勋章》便侧重于讨论角色的想法和感受。“我自愿参加,但我认为自己却是个懦夫。”

以不同形式讲述同样的故事:

书籍,电影和电子游戏可以讲述同一个故事。但是游戏中的乐趣却是源自与书籍或电影不同的方面。

在电影中,学习如何战斗只需要2分钟。而在游戏中学习如何战斗则需要好几个小时。这其实是一个完整的体验。

同样地,电影会花较长时间去描述角色发展。而在游戏中可能只会出现2分钟的过场动画进行描述。

是的,这的确太过简单化。你可以将行动与角色发展相结合,大多数故事都是这么做的。我们是为了清楚地呈现每种媒体的优势与劣势才这么区分。

这对于游戏中的故事叙述是个大问题。在这里传统的写作方法是无效的。当我们在玩游戏时,我们便会变成目标导向型,并且想要融入系统中。任何将我们带离系统的内容便是我们与目标之间的障碍。甚至连死亡都是系统中可察觉的元素。换句话说,传统的故事并不是这样。

过场动画:比死亡还糟糕?

在游戏中,死亡只是阻止我们在固定时间内靠近目标的暂时挫折。我们能够快速察觉到需要花费多长时间,然后按压“重载”按键并回到行动中。

而在游戏中,过场动画却是阻止我们在未知时间内靠近目标的暂时挫折。我们不知道这些角色要交谈多久,他们将会聊些什么,或者这是否会有趣。在游戏中,过场动画可能比死亡还糟糕。

我喜欢一定数量的过场动画,但我个人的忍耐度总是不到5分钟。当游戏强迫玩家长时间不能玩游戏时,它们将遭遇大麻烦。

游戏的成败取决于它们的系统。而传统的故事叙述却不适合当前的系统。

这种情况是否能够得到解决?

也许吧。

培养情感投入的最佳方法便是角色发展与互动。

在现实生活中,我们会进行许多基于目标的对话,即根据我们对于其他人的了解以及如何使用措辞。对话便是一种系统。

从理论上看,对话式互动系统可以是游戏的基础。如果玩家在靠近一个NPC时知道自己要的是什么,如果他们操纵对话系统的技能能够影响结果,如果系统是有趣的,那么这便是全新的游戏水平。角色发展与情感投入是不同步的。这是需要不断升级的。但事实上却不是那么简单。

游戏拥有神奇的力量能够控制玩家与游戏世界,敌人及其工具互动的能力。但是能够探索人类与人类间的情感互动系统却还未出现。

电子游戏中的枪支是一种简单,有趣且具有奖励性质的互动工具。而“按压A”开始进行对话却不是如此。枪战能够基于技能以及科学系的惩戒创造一个系统。但是分支对话树却不行。

在《模拟城市》中破土动工并观看着自己的体育场不断壮大是有趣且具有奖励性的。在《植物大战僵尸》中收集足够的太阳去设置你的第五个Melon Pult是有趣且具有奖励性的。在《极速快感》紧凑的回合中漂移是有趣且具有奖励性的。而选择“礼貌”或“粗鲁”的回应却不是。

如果缺少能够学习,操控与精通的系统,人类互动将继续作为游戏障碍存在着。

2.《偷天情缘》的问题

玩家总是会重新玩游戏直至得到自己想要的结果。

story-in-games-groundhog-day(from gamasutra)

在电影《偷天情缘》中,Bill Murray所扮演的角色因为一些不明原因将反复在同一天复生。每一天他都会尝试一些新事物,但每天早上他都会在同一天同一座城镇的同一张床上醒过来。在某种意义上来看他是被困了,但是他却可以做任何自己想做的事。

而电子游戏玩家却可以重玩任何情节直至获得自己想要的结果。设计师不会强迫玩家做出特定的决定。

重玩性非常强大。在游戏中我们可能永生不死,可以进行无数次的尝试。我们会利用每一条生命创造一个平行宇宙,而待得最常的那条生命便是能够带我们走向胜利的对象。第8个关卡中的boss可能会像房子那么大,并且还带有爪子,但是在游戏中并不存在任何能够与永恒的玩家进行对抗的事物。

Bill Murray说道:“我是God。”

Andir MacDowell说道:“你是God。”

“我想我是god,我不是God。”

“因为你从一次车祸中存活下来吗?”

“我不只是从一次车祸中存活下来。昨天我不只遭遇了爆炸。我还被刺伤,射伤,中毒,冻结,悬挂,电击,烧伤。但是每天早上醒来后我都安然无恙。如此看来我是神仙吧。”

在游戏中我们就是如此。而这便是一个巨大的故事叙述问题。

那些在其它媒体中影响着角色同时也在现实生活中影响着我们的恐惧与动机并不会影响我们的游戏角色。我们通常都会闯进一间陌生的方子,然后跳到20英尺高的屋顶并且未多加思考而向恶魔发动攻击。但是《偷天情缘》问题却会破坏紧张感,可信度,并造就玩家的能力与开发者所阐述的故事之间的矛盾。

如果故事中具有必然事件,玩家便不能具有关于这些事件的任何选择。玩家将选择他们想要的而不是故事叙述者想要的,他们并不是基于正常人的思维进行选择,而是基于神仙的角度做出选择。开发者必须仔细判断提供给玩家的自由度。

这种情况是否能够得到解决?

可能吧。

解决系统和《偷天情缘》问题是一条漫长的道路。如果NPC能够推动故事的完整,玩家的选择便不再能够影响主要的情节点,如此设计师便可以随意编写内容了。那么剩下的便是连接玩家动机与游戏世界了。

3.恐怖谷理论问题

如今的艺术和技术还不够先进,不足以帮助设计师在游戏中创造真实可信的角色。

存在一种情感动力是游戏优于其它媒体的:沉浸感。没有一种体验像《Thief》,《迷雾之岛》,《质量效应》,《Rage》或《魔兽世界》所呈现的游戏世界那般深入。电影通常只有3个小时,而书籍只会让你不断幻想而不是真正将你置于故事世界中。相反地,游戏创造出了能够长达好几周时间吸引你的注意力的世界。

但是当你接近那些华丽且精心勾勒的NPC时,所有的幻想都会破灭。那些控制思维的简单脚本是不能与能够控制行动的复杂脚本进行比较的。Alex Vance可能拥有一个能够不断改变目光交流层面的程序,但是如果你想听听她说什么,你就要做好听一些她对于你的钦佩之语的准备。虽然外观发生了巨大的变化,但是如今的NPC的内部结果却与1995年的没有多大区别。

我们非常了解人类。但是在游戏世界中最出色的NPC将会在30秒互动中表现出他的非人性。

恐怖谷理论是情感投入的巨大障碍。每次当Alex Vance重复一句话,或挡住你前进,或目光呆滞地站在远处时,你便会清楚他不是真人。她只是一个程序。

玩家已经适应了这种情况。我们能够创造与游戏中的神秘军团的情感联系。但是非玩家却能够比我们更清楚地看到一些更深入的内容。

我向妻子展示了《质量效应2》,但是比起被科幻般的声音与动画所吸引,她反而说道“对话好像不是很同步,是吧?”的确是这样的。对于一个看惯了Pixar那般高品质作品的人来说,《质量效应2》的确显得粗糙了。我们是来自一个按压X便能够看到Cloud做出回应的世界,而她却是来自一个无数团队将投入好几个月去调整巴斯光年脸部表情的世界。

如果没有了情感联系也就不存在故事了。

这种情况是否能够得到解决?

是的。我们正在解决这一问题。美术师通过讲述关于动物,漏洞,玩具,机器人或外星人的故事去避免这一问题。或者他们会围绕媒体的局限性而风格化游戏角色。再或者他们会使用无线传播和录音的形式将角色移到屏幕外部。所以在技术受限的时候,开发者也能够使用一些小技巧去更好地讲述故事。

结论:

游戏拥有讲述带有沉浸感,吸引力并且能够改变生活的故事的潜能,这是远超于其它媒体所讲述的故事。而在此之前我们只需要解决一些问题。我知道你们中的许多人正努力致力于解决这些问题。我也期待在不远的将来能够看到你们的创造性表现。

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

篇目1,Designing game narrative: How to create a great story

By Terence Lee

In this article, we talk about why storytelling needs to revolve around the interactive nature of the medium. Come and learn how to identify great game narrative, and to understand the importance of interactive – rather than cinematic – storytelling.

Imagine one day you are struck with a flash of inspiration: freshly seared onto your mind is a story, one that is undoubtedly the greatest tale ever conceived by Man. It has all the elements of a great narrative: a gripping plot, nuanced characters, and an evocative setting.

How would you write a book to convey this story?

First, let’s look at how the medium of literature works. Writers use words to express ideas, arranging them in ways that draw the reader into the world of the story. Writers use descriptive language to evoke the senses; they construct dialogue to reveal personalities; and they structure words into sentences, paragraphs, and chapters, to set the pacing and flow.

Now, let’s say you write your book while disregarding all of these guidelines. You use trite descriptions, a destitute vocabulary, and you reveal your characters in unsubtle ways. An excerpt of this book might read:

“It was a dark and stormy night. Bob was an evil man. He said to John, the good guy, ‘I hate you and I will kill you.’”

You continue to churn out the whole book in this horrible style, somehow still managing to communicate the bare facts of the amazing story you had in mind.

People who read the book would laugh. Even though it may actually contain the outline of an amazing story, it fails to properly put it into words – you could say that it didn’t take advantage of the medium of expression (literature). The story and the storytelling are not the same thing; you’ve only conveyed the facts of your story, but not the greatness of it.

Of course, you know better. Let’s say instead, you write the book beautifully, creating the best novel of all time. Great job! Now, you have a new task: you must convey your great story as a movie.

Now, let’s look at the medium of cinema. Whereas literature can be characterized by using words to present ideas over the course of time, cinema builds on that by adding a second dimension of expression: sensory input.

The audiovisual experience in a film is a whole new realm of possibilities for artistic expression. Whole pages of descriptive language in a book can be represented by a brief scene of imagery in a movie. A conversation between characters is now enhanced by their body language, their tone of voice, and the cinematography.

So, to make your movie, what do you do? Here’s one method: hand a random person your amazing, book version of the story, and film them reading it out loud. Perhaps you also sprinkle in some beautiful panoramic landscape shots. That counts as a movie, right? It’s got audio and visuals set to ideas presented over time.

Well, despite containing narration of the best novel of all time, the movie is a failure. Again, it did not take advantage of the medium of expression – the visuals and the audio are not used in a way that brings the story to life. Anyone who viewed it would laugh at how it tried to tell a story with complete disregard of the entire sensory dimension of cinema. If you’re just going to watch a movie of a guy reading a book out loud, you might as well just read the book yourself.

What about the beautiful, panoramic shots? They’re nice, but if you haven’t unified the narrative elements with the cinematic ones, then all they are is a distraction. The visuals and the audio are the primary vehicle for telling the story; they shouldn’t be treated as mere artifacts of the medium. The level of cinematic quality of the panoramic shots needs to be permeated throughout the whole storytelling; you can’t just segregate the story part and the video part. It’d be like trying to save that bad book we wrote earlier by sprinkling in Shakespeare quotes. You can’t just staple on pretty cinematics to a book and call it a film adaptation.

Of course, again, you know better – this is all obvious stuff. Instead, you film an amazing movie. Good work! With that achievement out of the way, you have one final task: to tell your amazing story using a video game.

We said that cinema was kind of like two-dimensional literature, the second axis being sensory input. Video games introduce a third-dimension: interactivity.

In books, depth comes from the words you read; in film, additional nuances emerge from hearing and seeing a scene. In games, you can discover further depth from doing the scene. With interactivity, you now get to experience the story firsthand. When you play as the protagonist, you have the opportunity to take on their motivations and emotions. You hear and see things via your own discovery, not from the guiding lens of a cameraman. We could say that video games communicate depth of narrative experientially, whereas cinema did it visually.

So, to adapt your story to a game, you do this: you take your amazing movie version of the story, cut it up into its individual scenes, and create a computer program that plays back the clips. You code some fun segments of gameplay that are tangentially related to some unimportant parts of the story, and then sprinkle them in between the movie scenes.

Well, despite having the best story, the best writing, and the best cinematic representation of it, the game again fails to take advantage of the medium of expression – it did not integrate the interactivity into the narrative. What about the fun gameplay sections you sprinkled in? Well, just like the Shakespeare sprinkled in your bad book, and the panoramic shots in your bad movie, those gameplay sections don’t do anything to advance the narrative. All you’ve done is segregate the game into its story parts and gameplay parts. No matter how fun the gameplay part is, no matter how good the story part is, if there is minimal overlap between the two, then you can hardly say that the story was successfully told through the medium of games. All you’ve done is staple gameplay onto a movie.

Now, people who play this game would laugh at how poorly the narrative is presented, right? Well, no, they wouldn’t.

You may be unsurprised to learn that almost all big-budget games present their narrative in that method — story, gameplay, story, gameplay, with minimal overlap.

Story versus storytelling

Wait-a-minute: this method isn’t actually bad storytelling, is it? I mean, people love these games, don’t they? They sell well, and people always talk about how good their stories are.

Well, yes, I would say that it is bad storytelling. Now, that isn’t to say that the games themselves are necessarily bad, or even that their stories are bad. Narrative isn’t automatically a crucial component in games, as it often is in film or literature. Interactivity is the defining feature of games – and indeed, games that excel in their gameplay are most often great games. However, a large number of games appear to have serious narrative ambitions, yet they try to tell their stories by jamming together the mismatching puzzle pieces of cinematic control and interactivity.

It doesn’t matter how good your story is. What matters first is how good your storytelling is, and that’s defined by what medium you’re telling that story in, whether it’s a book, movie, or game. The aforementioned games with big narrative ambitions have great stories but bad storytelling.

So what makes storytelling good, and how do we identify bad storytelling?

A note on game criticism

Before we answer those questions, let’s all get on the same page regarding some concerns: Isn’t this all subjective? If everyone likes it, then what’s the big deal?

Is the quality of game storytelling subjective? Only partially. A story-focused video game, like any form of creative expression, is an act of communication. The goal of a game designer is to communicate an experience and theme to the player. What’s subjective is the value of that desired experience and theme.

However, what’s not as subjective is the effectiveness of the communication of those ideas. Most game criticism about stories tends to discuss the subjective themes, while taking the clarity and presentation of the theme for granted. It’s like if critics were discussing the horrible movie that we made earlier, and rating it positively solely because of the content of the narrated story, overlooking the fact that the story is presented in a horrible way.

But people like these games; they have fun and they enjoy the stories. Well, I don’t mean to diminish their positive experiences. Rather, I hope to show that enormously greater experiences are possible. We have very low standards, mostly because there are such few good examples out there. This is reinforced by popular game journalism reviews, which really is just an extension of the game industry’s marketing arm, a symbiotic feel-good loop that ensures that only the most easily digestible game concepts are explored.

We think what we want are movies with a dash of interactivity, when there is actually an entirely unexplored universe of possibilities out there. Once you think about what the theoretically perfect game narrative could be, you realize that what we currently have falls drastically short. We already have works in literature and cinema that are close to ideal perfection, but we don’t even know what the ideal is in games.

The goal of this article is to show that games have barely even figured out how to present a theme, and that we should first focus on how to properly use the medium as a tool of expression before we start to worry so much about what is being expressed.

How to measure artistic quality

Before we talk about storytelling, let’s first talk about how to even identify good qualities in a game. One of the strongest indicators of artistic quality or good design is how effectively the individual elements work together to communicate the theme. In a good movie, everything should work to reinforce the thematic ideas, from the colors and the angle of the camera, to the music, acting, and makeup. If one of these elements instead contradicts the theme, then it sticks out and detracts from the power of the message, or at the very least, misses an opportunity to strengthen the message.

For example, in The Matrix, colours are used to emphasize the idea of opposing realities. All the scenes that take place in the simulated matrix world have a green tint built into the very props, wardrobe, and lighting, while all the scenes that take place in the cold and harsh real world have a blue tint. This visual cue helps the viewer subconsciously distinguish the contrasting worlds. It’s an elegant way to subtly reinforce that theme.

If the color palettes were instead chosen arbitrarily, the theme of contrasting realities would be that much weaker, that much less coherent. A good cinematographer finds and takes these opportunities in order to maximize the strength of their ideas. Likewise, in game storytelling, we also find opportunities to reinforce the message of the story with game elements like interaction and decision making. To ignore the theme while designing these elements is to have a weaker storytelling experience. This is a restatement of our earlier revelation, that we must take advantage of the traits of the medium in order to effectively tell a story in that medium.

A creative work made with this attitude feels elegant and consistent, because it manages to communicate many related ideas with few components. A less coordinated game instead feels unfocused, clumsy, and conflicting. If we want to identify weak storytelling, these are the attributes to look for, which we can detect by playing through a game and paying attention to see if our mind fills with dissonance.

Three kinds of dissonance

Cognitive dissonance – it’s an internal, mental conflict, and is usually quite subtle. It happens when you hold two conflicting beliefs or ideas in your mind at the same time. What kind of dissonance do we feel when we play these kinds of games? Here are three kinds that I’ve identified.

Conflicting experiences

The first – and most apparent – kind is ludonarrative dissonance. What does that mean? Ludonarrative dissonance is when you watch a game cutscene where the hero laments his distancing relationship with his family, and then in the next moment, you’re driving a car over a hundred people. Ludonarrative dissonance is when a great warrior ally monologues about how cunning and fearsome he is, only in the next moment, he’s running in circles, blocking your path annoyingly, and then gets shot dead instantly. It’s when what the story says and what the player does or experiences don’t match up.

This kind of dissonance happens quite often when you segregate the narrative and the gameplay, because the narrative is in the hands of the writer in one moment, and the player the next. It makes it hard to take seriously what the story is saying, because it conflicts with what we are actually experiencing.

“Who am I?”

The next kind of dissonance is a dissonance of identity. To explain this, let’s first back up a bit to the analogy of literature, cinema, and games as dimensions. Another way to look at this triplet is in their increasingly intimate point of view. Think about books: a lot of literature could be described as third-person storytelling: the events are verbally recounted to you by a third party – the author – and you interpret the words on your own.

Movies, on the other hand, are second-person storytelling: you watch the events unfold before your eyes, seeing things directly as they are. Lastly, video games are first-person storytelling: you are the actor living out the story. Instead of simply being told what’s going on, or watching it happen, you’re experiencing it firsthand!

However, in poor game storytelling, we often have a big dissonance regarding your identity. In one moment, you are the protagonist, exploring the world and fighting enemies. In the next moment, you jump out of your body and watch your character interact with others without your control, walking and talking on their own.

You’ve switched from first-person to second-person. Who are you? Are you the actor or the viewer? Games should be consistent with their point of view. It severely diminishes the importance of your actions if it constantly feels like the game distrusts you with making the important ones.

It diminishes the importance of your actions if it feels like the game distrusts you with making the important ones

One of the basic principles in writing is to show, don’t tell. If you want to convey that a character is nimble, don’t explicitly say “Bob is nimble,” show it: “Bob dodged the falling boulder.” In games, the principle should be to do, don’t show. Don’t just show a cinematic of your character dodging a falling boulder, do it: have the player dodge the boulder himself. Now it is the player themselves who feels nimble, instead of just his avatar. This conversion of character development into personal development is the key to immersive storytelling in games.

The problem with cutscenes

The last kind of dissonance is the weird modal shift that happens every time the game awkwardly tries to switch between “narrative mode” and “game mode”. One minute you’re playing a game, the next you’re watching a movie. It breaks the immersion, reminding you constantly that you’re consuming a piece of media. Not only that, it strips away any tension and emotion that was built up during the gameplay.

Imagine you’re playing an intense game where you’re fighting for your life. You’re in a really difficult segment: the whole time you’re on your toes and watching your every step, making sure you don’t make any mistakes. The stress and tension you are filled with is real: it’s genuine, tangible pressure, not just because your character is in a thematically tense situation with bullets flying and zombies shambling, but because you yourself are being challenged, trying to master the gameplay and pull victory out of a tricky situation. This part right here is good storytelling: the emotions the player is feeling matches up with the thematic situation at hand.

Converting character development into personal development is the key to truly immersive storytelling

While you are playing through this part of the game, all of a sudden, the camera zooms out, and now it’s a cutscene. Instantly, all your internal tension is gone. You put your controller down and sit back and watch. Even though the characters on-screen might now be engaged in an even more thematically tense situation, jumping from helicopters or something, you as a player don’t really care about that. Deep down inside, you know it’s just “movie mode”: anything that happens now is just supposed to happen; it’s all just “part of the story”.

Any mistakes you made before, during the gameplay mode, actually mattered: they caused you real world stress. But now, since you have no more control, any mistakes that you see your character doing during movie mode are all “part of the plan”. You no longer have skin in the game. You find yourself relaxing when it switches to this mode. You’re relaxing during the climax! What’s supposed to be the most intense part of a game is now the moment for your to ease your muscles and take a breath of relief. The game wasted a hard-earned emotional buildup in the name of being more “cinematic”!

Every time the game switches from gameplay mode to movie mode, your attachment to the player character switches from 100% emotionally invested, to 100% detached. That’s pure, jarring, dissonance right there.

Here’s another, very different example of this kind of modal shift, this one happening outside of games: silent movies. These films have pretty good cinematography and very good acting. You could say that they fill out the visual experience quite well. However, every once in a while, an intertitle comes up.

Intertitles are those fullscreen captions that describe what is happening or contain dialogue. During these captions, the film regresses back a dimension – it ignores the sensory experience, the thing that makes film unique from literature, and puts straight up literature on the screen. If we were to graph the progression of a silent film on our 2D chart, it would look something like this:

Over the length of the film, it generally maintains high levels of visual experience; however, whenever an intertitle comes up, the amount of sensory experience drops down to near zero. The exact same thing happens with game cutscenes!

When a cutscene happens, you ignore the whole dimension of interactivity, the thing that makes games unique from film, and put straight up film on the screen. Games with cutscenes are the silent films of games. At least silent films are excused by their technical limitations – no comparable excuse exists for games. The worst part is that the most important plot points tend to happen during cutscenes, while keeping you at a safe distance from actually participating.

Games with cutscenes are the silent films of games.

Let’s look at a counter example to cutscenes. The Half-Life series has an alternative approach: instead of showing a movie, they unfold the content of the scene naturally during the gameplay, and you never lose control of your character. Characters start talking around you, impressive visuals happen in front of you, but you’re always in control. You may be confined to a gated area during these parts, but you’re still free to walk around and examine things, and watch the action unfold while remaining in-character.

This works pretty well: the immersion is not broken, and you don’t change point-of-view – you never stop being an actor in the story experiencing things firsthand. It’s not perfect though: the formula does eventually get a little bit predictable, and the illusion wears away once you start realizing, “okay, I’m now in a story room,” but for the most part it works well, far better than a cutscene.

Explicit stories and player stories

We’ve talked a lot about what games are doing wrong. How do we improve our storytelling? To figure that out, let’s first take a look at the concept of narrative itself more deeply.

What even is narrative? Do all games have it? Do all games need it? Let’s lay down some definitions. First of all, there are two kinds of narratives in games: the first is the traditional kind, the kind we think of when we talk about plot, characters, and dialogue; and the second kind is the narrative of the player’s personal experience.

The first kind is what I call the explicit story. It’s what games are about. This game is about fighting off zombies. This game is about exploring the world and saving the princess. This game is about saving the world from aliens. It’s the aesthetic context of the game, explicitly stated by visuals, sounds, and words. Not all games have this kind of narrative, but it’s in most. RPGs, adventure games, and action games usually put a lot of emphasis on the explicit story. Other games eschew it completely, like many puzzle games and most traditional card games. Even a game like chess has a tiny amount of it: the game is loosely styled as a medieval war game.

The second kind of narrative is what I call the player story. It’s the player’s personal experience. As they play through the game, a lot of things happen in the player’s mind: they experience a variety of emotions, they develop perceptions and interpretations of characters and events, and they form relationships between their own actions and the on-screen results. These things all work together to create a different kind of narrative experience, one with its own pacing, characters, plot, and dialogue, separate from the explicit story.

A good player story should always be the end goal, while the role of an explicit story should be to support the development of a good player story.

Are these player stories actually real stories? Yes – in fact, players will often just outright tell these stories to others. Ask someone about their intense Tetris match.

“I was trying to beat my friend’s high score. I had a great start, but near the end I just couldn’t get a line piece. It was up to the final few rows, and finally I got one! I used it to put myself in the clear, and went on to beat my friend’s high score.”

That’s a real story. Maybe it doesn’t sound that exciting when you put it in words, but in the player’s mind, it’s a fully developed experience with a real conflict, climax, and conclusion. It’s felt deeply by the player, because it’s something that happened directly to them.

All games have this kind of narrative. Even a game like football has its own stories – people tell them all the time, recounting exciting matches and plays. Many games have both kinds, both an explicit story and the player’s story.

However, a good player story should always be the end goal, while the role of an explicit story should be to support the development of a good player story. A game with an amazing explicit story and a horrible player story is like the book we made earlier that had a great plot but a horrible delivery of it; it’s the movie we made with the bad narrator and boring visuals. You can’t just design both stories separately: as we saw earlier, fun gameplay that is segregated from the explicit story makes for dissonance, meaning you’ll end up with a disjointed and bad player story.

Unifying the two narratives

So how do we tell a good player story and a good explicit story together? By knowing this: the best game storytelling is when the explicit story is indistinguishable from the player story.

Ideally, when you play a game, you should never have to ask yourself, “What am I supposed to be doing?” In a good game, what you are supposed to do should intersect with what you want to do. If the emotions and motivations you feel while playing a game feel natural within the context of the game, then something amazing has happened.

In a good game, what you are supposed to do should intersect with what you want to do.

Here’s an example from the first Portal game. In this game, you play as a test subject with a portal gun, trying to advance through different test chambers. Near the end, you are riding a slowly moving platform to what you are told is a reward for your good test performance. Suddenly, it’s revealed that the platform is actually taking you to a fiery death.

When I was playing this scene, I genuinely panicked: I was deeply immersed in the game at this point, feeling good about myself for beating the puzzles, ready to be rewarded for it, and now I was being betrayed. Without thinking, my eyes lead me to an ideal surface for firing my portal gun, and I created an exit for myself, escaping certain death. For just a moment, I genuinely thought I broke the system. I had outsmarted the enemy with my wits!

Now of course, it turns out that I was actually supposed to do that. But when I did it, it was purely out of my own motivation for self preservation, not because I wanted to “advance the story”. There’s a night and day difference between just watching a character narrowly escape, versus doing it firsthand via your own wits and finesse, experiencing genuine anxiety and relief. A key plot element has progressed naturally, without dissonance. What I wanted to do and what I was supposed to do was the same.

Everything in the earlier parts of the game worked towards making this scene happen naturally for the player: the training in the portal mechanics; the witty dialogue that foreshadowed doom; the test chamber format that made you want to escape; the little hints that escape could be possible.

Let’s break this scene down to the two narrative types: The player story is that you used your wits to escape a stressful situation. The explicit story is that your character, Chell, used her wits to escape a stressful situation. They’re identical!

There’s a night and day difference between just watching a character narrowly escape, versus doing it firsthand via your own wits and finesse, experiencing genuine anxiety and relief.

Let’s compare this scene to a similar one in a different game. I’ll use the new Tomb Raider as an example, although there are countless situations in other games that play out the same way. In one scene, you are watching a cutscene of your character running from danger, and suddenly it’s revealed that a large boulder is about to crush you. You have exactly one option: press the × button within the next half second. If you do, your character jumps out of the way safely. Any other action causes your character to die.

On the outside, both scenes in Portal and Tomb Raider seem to have the same amount of danger: in both cases, failure means a gruesome death for the heroine. Yet in Tomb Raider, the situation is experienced largely emotionlessly by the player. Perhaps you cringe a bit when you see the grisly death animation, or maybe you experience frustration as you miss the button the first few times. But there’s never the excitement of using your wits to save yourself from danger, as there was in Portal.

Even though the Tomb Raider scene may be more cinematic and visually impressive, it’s forgettable. You almost got killed! Shouldn’t that be memorable? It’s not, because the player story clashes with the explicit story. The player story is that you’re watching a cutscene, and suddenly the game tells you to press a button in an obvious and annoying way, and you are forced to press it under the punishment of boring repetition. The explicit story is that your character, Lara Croft, narrowly escape grave danger using her keen senses and agility. That’s a huge disconnect between the two! How dissonant is that?

This is what I mean when I say that the explicit story is the aesthetic context to the player story. It’s a way of framing your actions and motivations, a way to increase consistency and to reinforce themes. The two narrative types work together. If there was no explicit story in that Portal scene, you would just be jumping from gray boxes into gray walls, so that you don’t fall into the red zone that would reset your position. You might feel good about figuring out the puzzle, or enjoy that you’re getting pretty good at the mechanics, but you wouldn’t feel like you “beat the system”, or that you used your wits to cheat death.

On the other hand, if there were no player story, like if you had just watched a really cinematic video of the situation, you wouldn’t have felt those things either. You may get excited by the visuals, or feel happy that the protagonist survived, but you wouldn’t feel any personal achievement or any risk to yourself.

Linear, scripted, cinematic stories

So we just saw a good example of how tell a good story of a short action sequence. How can we extend these principles to the entire story of the game?

Well, it’s hard. Not many games have pulled it off very well, especially games with a linear, scripted, cinematic format. By this format, I mean games with a big emphasis on the explicit story, with scripted events, lots of characters and dialogue, and usually a definite ending. There are a lot of weaknesses with this format: a lack of choice; an over-emphasis of dialogue, even though the player has little control over it; a rigid, linear progression. These aren’t weaknesses in a film, but in a game, these traits clash quite heavily with the medium’s emphasis on interactivity.

Portal is one of these games, but it manages to do a great job at storytelling. However, I think it is an exception, in that it is unique in its ability to take advantage of those weaknesses. The lack of choices, the one-sided dialogue, and the linear progression, all made sense in Portal’s test chamber format. You’re forced to do what is told, since you’re just a guinea pig; you can’t talk back, since there are no other characters except for a disembodied computer; and you only have one direction to go in those test chambers.

This convenient format means that none of the usual dissonances arise. But you can’t really generalize these techniques to other games. It’s as if the only way to overcome these weaknesses is by embracing them and building them into the story itself. That’s not an option for most game stories.

Maybe the linear, scripted, cinematic story just isn’t a great format for games. Some games with this format do a pretty decent job, at least in some aspects, but I doubt we’re going to see great advances in this style for a long time. It’s a style that is imperfectly adapted from movies, and it just doesn’t fit very elegantly in a medium about interactivity, choices, and personal experience.

I don’t think it should be the go-to format for game stories. What other formats are there? There are a few options, many of them experimental, but there’s one in particular I want to explore in this article: emergent narrative.

Putting the player back in control

We saw that the weaknesses with the linear, scripted, cinematic format all revolved around control. The writer in us wants to create a string of concrete events that unfold unvaryingly, but what if we loosened up on that desire? What if we gave up that strict control? A common thing we saw in those games is that they first created the explicit story, and then designed the player story around that. They have their script all written out, and then built the gameplay with the script in mind, trying to get it to match up. What if we did the opposite? What if we designed the player story first, and then built the explicit story to match that?

Now, I don’t mean to simply make a fun abstract game first, and then write a scripted story that makes sense with it. That’s certainly a great method to try out, but it’s not exactly what I’m talking about at the moment. What I mean is, instead of having any scripted elements at all, we let the explicit story describe the player story. We let the plot, climax, and characters all emerge from what the player experiences. In short, the story describes what the player did, instead of what the player needs to do.

What would that look like, exactly? Here are a few examples.

Journey

The first example is the game Journey. In the game, the explicit story appears to be very loose. When you start out, all you know is that you’re some sort of person or creature in the desert. That’s it. There are no explicit goals, motivations, plot, conflict or dialogue. However, these things naturally emerge, simply through the design of the game.

Early on, you see a beautiful, gleaming beam of light on a mountain far in the distance. Either consciously or subconsciously, your goal becomes to get to that mountain, as it always seems to be in your view. Along the way, you encounter some characters. These are other human players, going through the same experience as you. You can’t talk to them with words, but you can communicate with body language and a singing ability.

At this point, the story is different for everyone. Some people partner up with a curious new player, solving problems together, building up their friendship, reaching the end together. Others have conflicts with the other players, and choose to go it alone. Others make a great friend, but become separated from each other through their own struggles in the game, and they mourn the loss of their friend. Others find a mentor, an experienced player who can guide and teach them along their way.

These are all great stories that are deeply meaningful to the players, since they are personal experiences that they created for themselves. And they’re not just personal like an intense Tetris game, but also emotionally complex, like a good movie. I mean, imagine this:

You’re alone in the wilderness, and then you get stuck at the bottom of a cliff. You have great trouble getting out, but then a stranger comes out of nowhere and helps you. The two of you become great friends and you explore the world together. However, as you cross a windy bridge, your friend falls off!

You yell for him, hoping he hears you. You are filled with despair, knowing you may never see him again, but suddenly you hear him wailing faintly in the distance. You know that voice, that singsong pattern that you’ve heard him chirp before. Eventually, you go down and rescue him, as he had rescued you earlier. You journey to the end together safely.

That’s like something out of a movie! However, the experience is even stronger than a movie, because it actually happens to you. It happens not because a writer decided it should, but because of the actions you and your new friend did. You formed real relationships, felt real emotions, real despair and joy. A scripted version of the experience would only be a vicarious one; never a genuine, firsthand one like it is now. You could call it a literal narrative, since everything that’s important actually happens in real life, short of physically going into a mystical desert.

A scripted version of the experience would only be a vicarious one; never a genuine, firsthand one like it is now

It’s not that the designers didn’t design any explicit story. Rather, instead of trying to come up with very specific plot lines, characters, dialogue, and events, they chose to design a context that would highlight those elements when they emerged.

When you find another player, there are visual cues that underscore their presence and introduction. When you communicate with them through singing and body language, all sorts of imagery forms in your mind about the other player’s personality (that’s character development!). When you both are getting along fine, a big hazard tests your relationship. These are all elements of a great story, and they are explicitly designed by the designers. They’re just not shoved down your throat – they happen naturally.

Dwarf Fortress

Let’s look at another example. We talked about letting the story emerge out of the player experience; this game takes that concept to a whole new level: Dwarf Fortress.

It’s hard to describe Dwarf Fortress, but in short, it’s a detailed simulation of a kingdom of dwarves. It looks graphically primitive, but don’t let that fool you: the game is ridiculously detailed. This is a game that simulates everything from rivers cutting through canyons over thousands of years, to an individual droplet of rain on the eyelash of a child. It’s a sandbox game, and you try to build up your kingdom until a catastrophe naturally emerges through the complexity of the simulation, wiping everything away.

One great aspect of the game is that its visual simplicity allows your mind to fill in the blanks and assign meaning and motivation to the details in the game. It’s like how when you read a good book, your mind naturally creates what the characters look and sound like. Through this and through the game’s complexity, you can imagine what kinds of stories must emerge. DFstories.com catalogues many of these: some filled with action, some unexpectedly heartfelt and touching, others just plain silly. Check them out to see just what kind of imagination and emotions get stirred up by people playing this game.

While I would consider Dwarf Fortress to be on the extreme side of its style of storytelling, as it is quite inaccessible to most people, there’s still a lot from it that we can learn. The main thing we can take away is that an emergent situation – whether it came from the interaction of complex rules, the player’s experimentation, or even just through random chance – can be just as impactful to a player as a scripted situation, sometimes even more so.

The beauty comes when the situations feel purposeful and add depth to the player story. The fact that a situation is emergent means it’s likely unique, making the experience feel special for the player, since they know that no one else has encountered it before. It’s like when you play Minecraft the first few times and find a beautiful natural formation. You feel a sense of awe, knowing that you’re the first person to have ever seen it. It must be what old explorers felt when trailblazing. That’s a hard feeling to create with scripted situations!

Brogue

A final example of emergent narrative is a roguelike game called Brogue.

In Brogue, you are an adventurer exploring a procedurally generated cave, trying to reach the artifact at the bottom and bring it back up in one piece. It’s very difficult: death is permanent, and there are an infinite number of mistakes to make. The explicit story is minimal: all you know is what you’re looking for, and that the world around you is highly dangerous. Like Dwarf Fortress, the minimal visuals let the player form their own interpretations of the action.

However, the game is filled to the brim with opportunities for the emergence of great player stories. There are complex interactions between items, enemies, and the environment, and you always have a myriad of options for dealing with the current situation. Grass catches on fire; enemies can turn into allies; dropped items can trigger switches. There are so many interactions between individual elements, yet there are no scripted sequences. What kinds of emergent stories can arise from this? I watched my friend play the game once:

There he was, stuck on a wooden bridge over a deep chasm, goblins closing in on both sides, blocking the bridge exits. He is at low health and can’t fight them all. All he has is an unidentified potion, which he can only hope is a potion of levitation, so he can fly off the bridge to safety. With the goblins just steps away, he drinks the potion. Unfortunately, it was a potion of incineration!

A huge burst of flames erupts, setting him, the goblins, and the bridge on fire. The bridge burns away and everyone falls into the chasm below. Fortunately, he lands safely in a pool of water, which also puts out the flames. Some of the goblins survive, while others hit the ground nearby and die. However, one of the flaming goblins lands in a bog filled with explosive gas, and triggers a massive explosion that wipes out the remaining goblins. My friend escapes, and continues his journey deeper into the cave.

That scene is packed with action. It’s just as exciting as any action movie or game cinematic, and it’s just one of many equally amazing scenes that I’ve seen happen in the game. Despite that, none of it is scripted; it’s not even directly intended by the designer. It simply emerges from the interactions of the mechanics. The difficulty progression in Brogue means that as you get further in the game, the more elements you’ll encounter, meaning more interactions and more intense sequences like these will happen.

We should stop looking to cinema as inspiration for our narrative, and start realizing that nontraditional structures can be a stronger storytelling technique than the ones in the biggest scripted and cinematic games

A playthrough of Brogue truly does contain a genuine story: the story of the player’s adventure through the dangerous caves. Just because there aren’t names or dialogue or cinematics doesn’t make it any less of a story. I honestly think the storytelling in Brogue, despite the game being entirely untouched by plot writers, is superior to the storytelling in a game like the new Tomb Raider.

Yes, Tomb Raider has a more complex plot and more detailed characters, but remember: the story and the telling of it are not the same thing. Perhaps Tomb Raider would make for a better movie than Brogue, but we’re talking about games. Tomb Raider is that book we wrote at the beginning of this talk that has a good story but uses words and sentences poorly. Brogue is like Hemingway, with a simple plot, simple vocabulary, and simple sentence structures, but is written masterfully, in a way that deeply communicates its themes. I think the themes of action and adventure resonate much more deeply in Brogue than in Tomb Raider.

A new frontier

Emergent narrative is still a fairly unexplored technique, one that I think is particularly promising, since it delves so deeply into forming personal experiences. It’s one of many possible storytelling methods, and I think designers will have to first branch out in these areas if we want to discover the ideal form of game narrative. Until then, let’s remember to focus on the player story when building the explicit one.

Video games are a young medium of creative expression. Books have been around for millennia; cinema for a century. Video games became popular only just a few decades ago. We’re still just passing over the silent film era of games. I don’t think we’ve fully understood yet what it means to have great narrative in games, so we need to be open minded about different storytelling formats.

We should stop looking to cinema as inspiration for our narrative, and start realizing that nontraditional structures can be a stronger storytelling technique than the ones in the biggest scripted and cinematic games. Let’s redefine game narrative to mean more than just plot and dialogue – what we really care about is the story that happens in the player’s mind.

篇目2,How Bastion Blends Narrative With Play

by Andrei Filote

[Many games support their narratives via cutscenes and other non-interactive channels, but Supergiant Games' Bastion finds a way to work storytelling into its very core.]

Narratives and video games have always gone hand-in-hand. Even simple games like Pong find a way to tell their own stories, as players create their own experiences based on what’s happening on screen. Stories in games often emerge from the way we interact with them, but even decades after the medium’s inception, we still don’t have a solid consensus on the best ways to craft interactive narratives.

An exhaustive discussion of these methods will likely entertain scholars and designers for decades to come, but for now, it’s worth taking a look at a few examples that in my mind demonstrate a seamless union of gameplay and narrative.

How does narrative come about in a videogame? In essence, it all comes down to the way the brain assimilates information. Based on the way we process visual information, images lead automatically to narratives. This is convenient for games because — like movies — they are all pictures strung together in sequence! It’s important to note because that we often separate writing, dialog or story from play, but in reality they are as tightly interdependent as the two sides of a single coin. Since a videogame exists as a virtual environment, our perception of that environment and of what takes place within it automatically creates a story.

Many games today try to get the player to experience a written, pre-defined story on one hand, and on the other a series of interactions with the virtual environment, which create other, more spontaneous stories. Usually these two halves are kept separate by a series of constraints, whether technological or philosophical, so that we often experience them alternately (one section of gameplay leads into a corresponding cutscene and so forth). This creates a bit of a problem: proper storytelling is never addressed; as the stories that emerge during gameplay or cutscenes have little or nothing to do with each other. Thus, the whole experience becomes divided: One part is a game, the other is a movie contained within the game.

But despite this common problem, there are games that have found ways to work around the constraints of non-interactive cutscenes. One of the latest is Bastion.

Interactive Storytelling: Three Examples

The three instances we will be looking at are all underlined by the use of suggestion, a technique which is supremely suited to videogames but often ignored. It seems almost foolish to make use of something so understated in a medium that has a tendency to celebrate explosions, but the attention-demanding nature of videogames actually lends itself very well to suggestion.

While you are distracted with the challenges of the moment, something entirely different may unfold beneath the fabric of the immediate, creating ulterior motivation and providing new context to otherwise obvious actions.

1. When violence mirrors narrative

Violence is often a vehicle for play, but when the user spends most of his or her time physically destroying opponents, combat tends to become trivial, and it tends to lose significance in terms of storytelling. The critical subtext provided by Bastion’s use of suggestion changes all of this.

Consider first the game’s array of weapons. The progression in their technological advancement reveals the increasingly warlike aspect of the society of Caelondia. We witness a hierarchy of needs: to build (the hammer), to defend oneself from the environment (spear, bow), to dominate the environment (fire bellows), to combat other societies (carbine, musket), to dominate those societies completely (mortar, calamity cannon), to unleash the end-all weapon itself — the Calamity.

The progression follows the development of the story and its themes. The more destructive your weapons become, the closer you get to learning the truth about the equally destructive conflict between the City, founded by colonists who seek to exploit nature and harness its forces, and the Ura, who still live in a world of inviolate divinity.

It’s a remarkably simple history of a society’s violent deeds. As the colonists penetrate the new continent, they trade hammer for bow for musket for cannon. The Calamity, with its ability to sunder mountains and render any living being into ash, is a surreal nuclear weapon. It is also the logical extreme of the arms race and at the same time the ultimate guarantee against defeat. It’s fitting that the game take place in the backdrop of the Calamity, because in attempting to reverse it the Kid has no choice but to come to terms with the reality of its deployment. Having just escaped it, he is embraced by it.

2. Contextualizing the enemy

Your enemies are neither anonymous nor without motivation. They occupied different roles before the Calamity and must now scramble to rebuild themselves. Their efforts come into conflict with the Kid’s, whose goal of rebuilding the Bastion is, according to the narrator, a victory for everyone. Whether we can trust the narrator is one thing, but this justification suddenly provides a sharp counterpoint to the killing of the sentient creatures who are attempting to create their own version of a safe haven.

The realization that your enemies have as much right to survive as you is a critical part of the game and is present most obviously in their opposition to the Kid, in their struggle to organize, regroup and rebuild, looking clearly to path out a future in a world which must recover from apocalypse. These are clearly the efforts of someone who has something to gain and to lose. The Windbags, a lower social order now displaced but inheriting a ruined city; the Ura, whose survivors focus their grief into vengeance, though not so much as to forget honor; the Peckers — birds with a “post-calamity superiority complex” — who are a humorous if irritating addition. Each are clearly acting on their own motivations, and are willing to use their resources to accomplish their goals. In so doing they are simply mirroring the Kid’s actions, and are being just as definite, as resolute.

Bastion’s antagonists are not evil. Nor do they rush blindly to their doom. Most of the time they are the natural world, or the lesser part of society, or a different society altogether.

They are all, undeservedly, subject to the violence of an invader: You. It is important to spell out this achievement, because Bastion doesn’t simply spill out hordes of automatons for the player to gun down. It provides context for its antagonists, which helps the game become something more.

3. The Shrine

The Shrine as a concept executes a perfect marriage between two separate needs: one, strictly narratological, to explain the faith of the Caelondian people, the other, a function of gameplay, to enable higher difficulties. Both of these are achieved through the act of praying. Prayer itself exists on two levels. The first level is that of the interface, which tells us, the player, who we are invoking and what we are getting for our trouble (enemies hit harder, faster, etc). But in the story proper there is no interface, and from the Kid’s perspective there is no user: His prayer is an act of pure faith, and like swinging his hammer, it’s no make believe. He makes a decision, reaching out into the unknowable to ask for something.

What does he ask for? We never know. What we get is difficulty, trials, and tribulations, all of which constitute one thing: Punishment. Is it too far a leap to guess the Kid believes he deserves to be punished for the crimes of the past? We can only wonder, but wondering is in itself both reward and achievement — to have created characters who own their lives and act on their experiences, who, in short, live every moment as intensely as we do, as though they have broken away and now live independently, occupying a space we have the privilege to touch. That is the goal of any narrative, whether it comes in a game, film or novel.

These considerations can only be made through the use of suggestion, through those silences and whispers which tell us enough to get by, but which conceal an entire world left to the imagination. Beneath the surface of its beauty, behind the lush color palette, beyond even the physical world which comes together spectacularly at the player’s feet, Bastion is a game of ethnic conflict, even of genocide, and of many, many mistakes.

An exceptional element: The narrator

Plenty of video games have used narrators to support their storylines, but there has never been one quite like Bastion’s, which is all-encompassing, and reactive to the player’s actions.