系列分析:与用户留存和游戏沉浸相关的逻辑分析,上篇

篇目1,分享令玩家持续玩游戏的建议

作者:Jennifer June

假设你已经发布了自己的游戏,恭喜你,终于让它面世以便人们都能来下载。但你开发了游戏,用户就会如期而至吗?来自巴西Square Enix拉美公司的Sabrina Carmona在最近的Ottawa国际游戏大会(OIGC)上发言分享了开发者如何在发布游戏后其游戏活跃性的看法。

为了跻身美国App Store前100名热门免费应用榜单,你必须实现将近7万次的日常下载量。除此之外,还要知道多数玩家会在下载过后删除游戏。Carmona所谓的“第一次约会”就非常适合描述这种情况:你如何精心设计自己的约会以便获得第二次机会?你该如何维持这段关系?“你该如何获得好运?”

用户获取——邀请玩家

dating1(from gamezebo)

Carmona描述了三种用户获取类型:自然,付费和额外努力。自然增长可以描述为基于低成本甚至是零成本的用户获取方法,例如极出色的图标,富有吸引力的截图,优化的视频或预告片,有趣的游戏描述,良好的评价和适宜的关键字。如果执行得当,你就要以获得相当的流量,并且赚得一些收益。而付费方法,例如广告营销,交叉推广和电邮营销则成本昂贵,但通常回报也很可观。

最后就是额外方法。Carmona解释称这正是你可以真正发力,让游戏绽放异彩,从其他游戏中脱颖而出的地方。可以利用社交媒体做一些与众不同的措施,撰写独特的新闻篇或者在关键应用评论网站上获得一些好评,这可以让你的游戏获得额外的关注和青睐,也的确是值得一试的方法。

用户参与度——获得再次约会的机会

dating2(from gamezebo)

现在你已经有了一些玩家了,就得想想如何保持他们的兴趣。通过分析找到玩家是有效用户粘性的最重要层面之一。“谁在玩你的游戏?我们该如何取悦他们?”这一信息对你的用户参与方法(如游戏活动和更新内容)来说甚为关键。

为了证明活动执行的有效性,Sabrina以手机游戏《Puzzle & Dragons》(游戏邦注:首款收益达10亿美元的游戏)为例,该游戏精于使用活动事件保持用户参与度,并将休闲玩家转化为中核玩家(Carmona将这些玩家定义为围绕自己的生活安排游戏玩法的群体)。这些活动事件可以是季节性的(“圣诞节来了!”),限时特价活动(“欲购从速哦!”),周期性(“仅限周二!”)或者融入社交媒体(“分享此贴!”)。每种类型都能很有效地触及玩家心理,令他们产生一种“我最好重返游戏”的想法。

Carmona称更新内容也能够有效吸引你的用户群体返回游戏。但有一个普遍误区就是一次性将你的精彩内容托盘而出,所以千万不要轻易发放这些内容,而要让他们渴求内容。要逐渐而缓慢地透露新内容和新功能,为玩家创造一种兴奋感。

用户留存——让用户渴望更多内容

dating3(from gamezebo)

推送通知和留心用户反馈是令用户持续返回游戏的两种最佳方法。据Carmona所称,发送推送通知的“明智”方法,就是瞄准游戏中的细分休闲玩家发送通知,不要去招惹游戏已经虏获的忠实玩家。

提供有效的客服支持也是漫漫长路,但很有必要在处理大量用户反馈时将付费玩家置于首位。总是确保任何玩家抱怨(尤其是在社交媒体上的抱怨)能够得到热心的解释道歉和保证。当用户提供反馈时,要记得向对方道谢谢。当他们针对游戏提出良好的建议时,那就去执行吧!

用户盈利——获得好运

dating4(from gamezebo)

现在又回到手机游戏行业的老话题:你该如何让用户掏钱?Carmona称在吸引那些需要微交易的玩家时,掌握诱导性销售的艺术极为重要。

有一个方法就是有效传递交易价值,必须让用户觉得自己的交易的确物有所值,可以让自己的生活更轻松。实现这一点的出色方法就是抓住时机,适时向用户提供其所需的升级道具或内容。当然,你必须教会玩家如何消费(这一点必须在教程中体现)。

所以即使你能够通过发布游戏证明自己有多棒,你可能也会需要执行这其中的一些建议和窍门,以确保自己的游戏在竞争激烈的市场中占据一席之地。让用户为了获得更多内容更持续重返游戏,你就有可能实现每日7万次的下载量了,也就有望跻身前十强榜单了!

篇目2,如何在游戏中创造长期的用户留存

作者:Mikkel Faurholm

长期用户留存是面向App Store和Google Play发行游戏最重要的元素之一。因为市场上有许多免费游戏,所以你必须想办法让自己的游戏能够在一开始就吸引玩家的注意并让他们沉浸于游戏故事或主题等内容。一种被低估的长期用户留存策略便是通过创造玩家可能在游戏中变成什么的目标而吸引他们留在游戏中。有些游戏尝试着通过带有戏剧性的背景故事,能让玩家产生共鸣的“帮助者”以及在游戏环境中作为新的主导力量的任务去吸引他们的注意。这特别呈现于瞄准像如下成人那样的侧脸游戏/建造游戏。

关于这种类型的用户粘性策略所存在的问题是玩家很少会与“帮助者”进行互动,从而让这种策略只能在一开始发挥作用,而不能作为一种长期策略。在某些情况下这样的帮助者将变成像MS Word在1997所推出的Office Assistant Clippy,并最终将与我们的预期目的相违背。

为了提高长期用户粘性,游戏需要为玩家创造一个目标。清楚地呈现出这个目标,玩家可能变成什么,在他们面前会出现多酷的功能等等。很多人不能有效地创造这些目标。大多数玩家在游戏中都不知道自己接下来该做些什么。这与重新摆放家具能够帮你更好地卖掉房子是同样的道理。也许买家搬进去的时候家具不一定还是在原来的位置上,但是如果你能够重新摆放家具,便能够让他们看到自己未来的住处的雏形。

以下是一些有效地将这种模板呈现于玩家面前的优秀游戏例子,也有一些在这方面碰壁的游戏。

让我们先从正面的例子开始

Supercell的《Hay Day》在一开始便向你介绍了邻居Greg,他是一个热心的好邻居,在第一艘船到达时他会提醒你晒干草。而在玩家开始真正过上农民的生活前,友好的Greg会先向你呈现自己的农场。玩家在一开始便能够了解到游戏中可能出现的内容以及他们将面对什么。这是游戏长期吸引玩家的绝妙方法,他/她总是想要获得与亲爱的邻居相同的东西。

Hay Day(from gamasutra)

让我们继续看另外一个优秀的例子,同样是来自Supercell的一款游戏,《Clash of Clans》。这款游戏也发挥了同样的作用,即使是基于一种不同的方法。在游戏一开始将会有一个很贴心的女人告诉你要尽快创建一个大炮。很快地你将遇到其中的一个主要机制,也就是攻击其他玩家并赚取排行点数而在排行榜上进行攀升。在排行榜菜单上有着“最佳部落”和“最佳玩家”的标签,这便是这款游戏最突出之处。在此你将面对的是真实的玩家,而不再是Greg。

接下来让我们着眼于一些在这方面遭遇失败的游戏。

与《Clash of Clans》相同的是,《地下城守护者》在战役中引进了袭击机制,让玩家能够快速攻击其他玩家。看下图,左边是我自己在1个小时游戏后的情况,而右边则是游戏世界中最出色的玩家的成绩。其中的区别自然很明显,但却未能创造出目标和长期的吸引力。如此我还会愿意花大量的时间待在右边的地下城中吗?!

.jpg)

Dungeon Keeper(from gamasutra)

另外一个常见的误区便是游戏的结尾,最后的boss应该是较为隐秘且不容易被玩家所打败。这是8,90年代的电子游戏玩家想要的结果,但休闲玩家却不是如此。如果玩家不清楚自己的时间都浪费在哪里的话,他们便会对下一款游戏更感兴趣,因为他们不知道接下来会发生什么。瞄准休闲玩家的游戏就需要呈现给玩家前方可能出现的内容。所以开发者就必须在游戏中创造适当的目标。

人们并不需要打开像经典的平台游戏中那样的世界。如果你能够呈献给玩家通向最后的完整道路,他们更有可能继续游戏,甚至有可能愿意为游戏打开钱包。

你应该通过游戏玩法和有趣的机制与社交功能去吸引玩家的注意。但同时你也必须为其呈现出完整的轮廓,告诉他们接下来会发生什么,并创造明确的目标。

篇目3,多人游戏机制和比赛将提高手机游戏的用户留存

作者:Gabriel Cornish

随着手机游戏市场中的竞争性逐渐增强,在此争取成功变得越发困难;登上排行榜榜首之位也不再能够保证每个月的高收益了。随着更多高质量的新游戏的不断涌入,即使是最受欢迎的游戏也比之前承担着更大规模的玩家基础流失。结果便是,所有游戏的留存率都在下降,而最成功的游戏也在拖着盈利率和游戏终生价值往下走。

提高手机游戏留存率的一大方法便是引入多人游戏功能。在今天的市场上,单人游戏因为种种局限已经开始失去魅力了,如它们的游戏玩法要么就是不断重复着,要么就是基于内容长度而不断延伸。大多数单人手机游戏只能维持玩家至打败游戏,或直到他们厌倦了核心游戏机制。而多人游戏能够通过创造更具竞争性和社交性的内容而刺激玩家不断尝试游戏玩法。有些强调了多人游戏功能的手机游戏甚至延长了50至100小时的游戏寿命。

多人游戏能够带来社交氛围,并将游戏玩法带向一个全新的高度。随着团队合作和竞争机制不断出现在游戏中,玩家更加愿意频繁,投入且长时间地游戏。此外,玩家也会因为受到游戏的推动而将自己的朋友带入游戏中,彼此竞争,从而创造了一种免费且高质量的用户获取渠道。社交游戏能将一些具有共同兴趣的陌生人集中在一起,创造一种全新的关系并围绕着游戏组建社区。

多人游戏添加了一种全新的游戏局面,即培养了投资型玩家,他们更愿意生成利益并不愿意轻易退出游戏。举个例子来说吧,在《War Metal: Tyrant》中,宗族中的玩家的ARPU值是普通玩家的20倍,(游戏邦注:即《Tyrant》55%的收益是来自6%的宗族玩家)。你认为哪些玩家更会坚持玩游戏?

多人游戏本身可以通过比赛等实时活动而不断完善。比赛能培养时间限制所创造的竞争氛围。而竞争的即时性能够提高应用内部购买的可能性,并强化游戏玩法而提供更具有奖励性的体验。这不仅能够打破单一的内容为玩家创造全新的游戏体验,同时与周期性内容结合在一起也能够确保游戏的新鲜。游戏可以为比赛的胜者设置真实和虚拟的奖励,提供强大的动机促使他们参加更多比赛,特别是当比赛是基于获胜次数而非分数时。

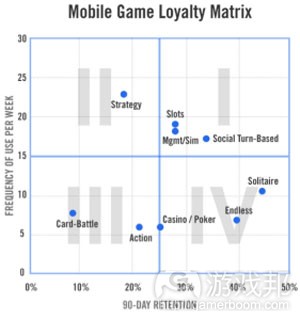

mobile-game-matrix(from gamasutra)

就像图中显示的,如果开发者想要提高用户的忠诚度,那么他们就应该标准表中的I范围。在这一范围内,我们可以看到90天用户留存和使用频率的最高值。多人游戏机制和比赛如果是以普通的街机游戏为终点,那便有可能位于表中II和IV的范围内,但却能够向I范围的回合制社交游戏而转变。在图表中,范围I是最理想的位置,即同时拥有高使用频率和高用户留存率,《神庙逃亡》和《愤怒的小鸟》等大受欢迎的应用便属于这一范围。毫无疑问,多人游戏机制和比赛能够帮助游戏进入这一范围。

篇目4,探索游戏的新内容和玩家留存理论

作者:Alexander Engel

我之所以选择谈论这一话题,是因为当我们在阐述如何创造游戏的细节时,玩家们对此都很好奇,所以我决定在此与大家分享。

我所思考的问题是,你是如何比较留住新文件与为旧玩家创造内容的利益?同时我想声明的是,本篇文章会偏向理论化,所以不会反应我们(或其它游戏公司)的实际操作。

答案出人意料的复杂。该问题的基础在于,对于玩家来说一款游戏的乐趣可以维持多久。我仔细思考了这一问题,并想出了一个简单的等式去计算平均每个玩家需要花多少天时间才能玩遍所有游戏内容,即到最后他们已经找不到其它事情可以做了:

((H + C + X) * E) / P = L

H表示每周创造内容的小时,C表示已经存在游戏中的内容,X则是每周让玩家沉浸于其中的内容。乘以游戏诞生的周数(E),再除以玩家每天的平均游戏时间(P),你便可以得出平均玩家消耗掉游戏内容需要多少平均天数。找到这些变量你便能够发现复杂之处。

为了明确每周出现内容的时间,我们需要着眼于一些其它变量:带宽(D),即每周团队贡献于游戏中的时间;漏洞修复(B),每周团队致力于漏洞修复的时间;项目时间(J),每周团队致力于项目的时间(包括性能,其它平台,参数,商店等);以及创造1小时游戏内容需要花费多长带宽时间(K)。如此,H的公式将变成:

(D – (B + J)) / K = H

为了明确每周平均玩家所参与的玩家间活动,公式变得较为简单。将玩家每周参与的PtP活动总数乘以他们每周花费在PtP上的平均时间,再除以那一周登录游戏的玩家数量,最终便会得到有关X的公式:

(A * B) / D = X

为了测试这一公式,我们需要分配一些变量。一开始我擅自将随机数字带进这一公式中,不过这并不能代表我们的真实工作和所花费的时间。所以让我们假设这是关于一款假想游戏《太空牛仔》(我在前天晚上所创造的)的公式。

在分解后,我们最后的公式如下:

((((D – (B + J)) / K) / E) + (((A * B) / D) * E) + C) / P = L

让我们记住,这一假想游戏已在180天前发行了,它的名字是《太空牛仔》。我们一直在追踪这款游戏的玩家数量,并且可以将其整合到公式中。基于这些任意数字,我们最终获得的结果是:

((((180 – (120 + 40)) / 8) * 10) + (((200000 * 5) / 300000) * 10) + 100) / 2 = 91

是的,我知道自己的计算和公式非常混乱,一点都不完美。

所以最终的结果便是,在我们的任意游戏发行10周后,我们的任意玩家将会在玩了91天的游戏后耗尽所有内容。假设玩家每天平均游戏时间为2小时,每周发行新内容的时间为5个小时,每周2/3的玩家平均花5个小时于PtP活动中,每周共有30万名玩家在玩游戏。这也假设了我们会在10周之后停止创造内容,而玩家也会在10周之后停止进行PtP活动。

但是等等,我们似乎漏掉了什么!我们忘记了一些非常重要的事:并不是所有玩家在玩遍了所有内容前都是无限期地玩游戏。相反地,许多玩家会在游戏中的某个点上感到疲乏并选择离开游戏。世界上,对于大多数游戏而言,大部分玩家都是在注册后便选择退出,并再也不会回到游戏中。所以对于我们的假想游戏,让我们为100万名玩家在第0天(也就是我们的发行日)注册后设置一些虚构的流失率:

第0天——留存率:100%—-玩家:100万

第1天——留存率:75%—-玩家:75万

第15天——留存率:50%—-玩家:50万

第30天——留存率:40%—-玩家:40万

第90天——留存率:25%—-玩家:25万

所以我们的第一个公式所确定的是玩家耗尽所有内容的平均时间。我们还必须明确多少假想玩家会在遇到这种情况时继续游戏。使用上述数值,我们可以发现在第90天时会有25万名玩家仍在玩游戏。那时候,平均玩家将耗尽所有内容,即意味着12万5千名玩家将无事可做。而另外12万5千名玩家将拥有一些全新的内容,但是关于具体有多少内容则是个变量。

总的来说,“忙碌中的玩家”(游戏邦注:即并未离开并仍有内容可做的玩家)的数值情况如下:

.jpg)

player trends(from gamasutra)

我们可以估算,直到第180天,《太空牛仔》将剩下10万名玩家,因为他们停止玩PtP,并且耗尽了所有可行的内容,所以现在将没有人愿意再玩我们的游戏了。着眼于图表,我们早在第90天的时候就开始注意到这种情况了,那时候许多玩家开始选择退出,而其他玩家也已经完成了所有内容。如果我们能够创造更多内容的话便有可能改变这种情况,即能够提高玩家的留存率并吸引更多新玩家。

为此我们需要添加更多内容到表格中:每当我们去获取玩家时,会出现多少新玩家开始玩我们的游戏。为了呈现出这点,我混合了2种玩家群体,即包含了一群在游戏发行15天后获取的50万名玩家以及一群游戏发行30天后获取的25万名玩家。这从本质上改变了结构,因为除了最初的100万名玩家,还会有50万名在第15天开始游戏,并且在第30天后又会出现25万玩家开始游戏。结果如下:

.jpg)

175k players(from gamasutra)

这看起来还是很糟糕。直到第180天,尽管我们的玩家数量增加了75%,最终也只有少部分玩家仍继续游戏。所以作为游戏开发者,我们需要如何做才能阻止这种情况?我们可以想办法改变留存率。如果我们能够找到方法在每个阶段提高5%的留存率,我们便能在玩家耗尽所有内容前增加玩家数量。

直到第15天和第30天,便会有超过100万名玩家在玩《太空牛仔》。看来提升5%留存率的方法还蛮有效。但是因为在第180天时玩家也会耗尽所有内容,所以他们最终也会选择离去。而如果我们能够双倍增加内容,将耗尽日期往后延长,同时保持留存率,结果便会得到有效的完善:

.jpg)

double content(from gamasutra)

如此,直到第180天,我们便拥有之前3倍的玩家仍在玩游戏。尽管玩家总数仍然很低。这便触及了图表的最大限度,因为我们只能延伸到第180天。我们将发现在180天后仍会有许多玩家继续玩着游戏,这将长于基础模式或留存模式。这一模式就像扣篮一样,但是这里所存在的最大问题是内容创造太过昂贵。在游戏中双倍增加内容需要我们投入更多的工作时间并组建更大的团队。我们在上述所提到的数值,也就是8个小时的开发时间只适用于1个小时的内容中。这便意味着如果要双倍增加内容(游戏邦注:从100个小时延长到200个小时),我们就需要投入800个小时的开发时间。这些时间都可以用于创造新图像,新工程,新设计,执行过程,QA测试,并确保我们不会破坏现有内容等工作中了。

我想要在此强调的是,创造更多内容并不是你可以轻松打开或关闭的旋塞。在Disruptor Beam(游戏邦注:专注于用户社区以及网络游戏领域的游戏开发商)中,并不是所有人都能在任何地方发挥自己的技能。就像我便不擅长创造游戏系统或编写代码。而雇佣其他人去完成一些额外工作则需要花费大量时间。不管是雇佣过程,面试,浏览简历还是执行其它扯到法律的工作,我们都需要花上大量时间才能找到一名合适的候选人。在那之后,这些候选人还需要经历相关培训才能真正开始研究问题。这将需要几周甚至几个月的时间,并且可能会在好几个月后才会带来帮助。

让我们着眼于《太空牛仔》最后的比较数值:

.jpg)

base vs content and retention(from gamasutra)

我们必须通过增加游戏的粘性而想办法达到平衡,即意味着提高玩家的留存率以及我们创造内容的速度,特别是在一开始。在某些情况下,你的大多数初期玩家将会退出游戏,但是你也可以通过游戏更新,扩展与改变将其再次带会游戏中。你需要记住的是,尽管内容创造非常昂贵,但是获取用户也不便宜。我们必须综合考虑方法所带来的利益及其需要花费的成本。

平衡新玩家,用户留存以及新内容是区分一家成功在线游戏公司与不成功的公司的主要元素。在Disruptor Beam,我们便非常希望能够承担这种挑战,从而让玩家可以在《Westeros》中感受到最大的乐趣。

篇目5,阐述免费玩家在用户留存与盈利方面的重要性

作者:Greg Richardson

众所周知,免费游戏已对游戏产业的发展产生了深远影响。其最初的成功很大程度是取决于无摩擦的覆盖范围。由于移除了预付门槛,游戏的用户规模会扩充10至25倍。现在,任何拥有智能移动设备或能联网PC用户都属于免费游戏的潜在玩家。

然而,为了推动免费游戏的发展,并瞄准更多用户群,我们必须遵循一定的设计原理(有可能是反直觉的):即游戏中的免费玩家其实比大开销者更有价值。免费玩家能够创建粘性社区,通过口口相传去推动游戏病毒性传播,能够最大化地提高游戏的长期用户粘性与盈利。如果你希望避开Zynga等公司近近期所遭遇的麻烦,并像Riot Games等公司一样撞去数十亿美元的收益,你就需要学会善待免费玩家。

如今,大部分免费游戏开发商总是极力避开免费玩家,着眼于少量的大手笔付费用户(游戏邦注:即鲸鱼玩家)。针对鲸鱼玩家设计的游戏致力于在玩家生命周期的早期阶段创建盈利摩擦。其实,这种挑选过程会削减98%以上的新玩家数量,因此,开发者只能将重点放在余下2%的付费玩家身上。但是在这些玩家中,仅有一小部分有意愿且有能力为游戏支付大笔费用。因此,有些游戏的收益将变得很扭曲,即50%的收益是来自付费用户,而这些付费用户仅占总用户数的0.0004%。

随着免费游戏市场的不断进化,以及Facebook平台与智能移动设备上面对鲸鱼玩家的游戏数量不断增加,游戏产业出现了极端尴尬的境地。尽管开发者有能力吸引数十亿潜在玩家,但乐意支付上千美元的鲸鱼玩家数量相对较少。而且,鲸鱼玩家不可能在任何时间投入大量金钱于各种游戏中。结果便是,游戏公司逐渐发现,那些针对鲸鱼玩家的新游戏相比早前的游戏变得更加糟糕了,甚至会对当前游戏的鲸鱼用户带来影响。

免费玩家

事实上,免费玩家对那些想要为股票持有者们创造长久价值的游戏公司来说更具价值。原因如下:

最棒的免费游戏都是受社交性驱动的游戏。这种游戏的娱乐价值便是,要么从本质上推动玩家与玩家间的交流,要么满足玩家的物质需求。通过设计出能够让免费玩家能够长期沉浸于其中的游戏,你便能够创造出一种社交粘性,并最终提高付费用户的留存率。这是一种常识。谁会把自己存储数个月的积蓄砸在好友和邻居都不看好的全新宝马车上呢?

此外,免费玩家是你目前以低成本获取高品质玩家的最优途径。喜爱游戏的免费玩家会以早前的方式对游戏进行病毒式传播:他们会邀请好友尝试他们所喜欢的游戏。所以,比起支付一半的费用去吸引新用户,而后看着他们在一周内相继离开游戏,你应认真设计出免费用户苏喜爱的游戏,如此你便能够大大降低用户获取成本。

而且,有关免费用户的一个有趣现象是:他们在免费游戏上投入的时间越长,他们更有可能转化为付费玩家。那些持续在新游戏上投入一个月时间的免费玩家比起你花钱去获取的玩家更有可能转变成游戏的付费用户。当你的游戏能够迎合更多不同类型以及不同区域玩家的喜好时,你专注于免费玩家而获得的利益优势也将变得更加明显。其实,同比那些具有支付上千美元能力的玩家,世界上有更多玩家乐意为自己喜爱的游戏支付5美元、10美元、甚至是25美元。

长期价值

LOL(from lol.cespc)

如今市场上最具盈利性的两款免费游戏都避免采用基于鲸鱼玩家的盈利举措。Riot Games的《英雄联盟》与WarGaming.net的《坦克世界》已经决定将游戏设计与盈利举措的重心放在长期的价值创造上,即优先考虑免费玩家。

与追崇鲸鱼玩家的竞争者不同,《英雄联盟》与《坦克世界》致力于将更多玩家转变成付费用户(游戏邦注:有时会达到针对鲸鱼玩家游戏的10倍)。他们不断优化游戏设计并不是为大型消费者服务,而是让玩家能够根据自己在游戏中所投入的时间去决定最终消费,如此便有效地提高了用户留存,取得高效的口口相传结果,并提升了玩家的平均终生价值。

《英雄联盟》与《坦克世界》均决定不强迫玩家在游戏中“消费”。他们优化的定价与推销系统始终是针对小型与中型交易模式,而不是出售高价道具。他们会为免费用户开放大部分的游戏内容,并确保在玩家决定付费时能够最大化地向他们传达游戏价值——这便是一种良性循环。

免费玩家能够降低整个用户获取成本,而付费玩家会有更愿意为游戏付费。所有玩家都能在游戏中与其它用户共同体验,因为整个体验模式中存在大量可以构成多人模式与社交互动性的团队成员与对手。如此便能提高游戏的用户留存;而更高的用户留存也意味着转化率的提升,最终,玩家向游戏掏出了更多钱,游戏也将因此获得更大的利益。

然而,要设计出达到上述所有目标的游戏存在一定难度。首先,开发者英国基于盈利系统去创造真正的游戏乐趣。让玩家成为其他用户眼中树立起独特或仁慈形象具有强大的推动作用,而如果游戏仅在付费时才能体现出乐趣便会挫败他们的兴趣感。不要轻易让免费玩家遭遇失败,如此你便很难推动着他们为游戏掏腰包。

免费游戏具有无限的发展潜能。随着浏览器、智能手机、平板电脑与Facebook的发展,游戏将以迅猛之势覆盖全球大部分用户。而实现这个想法需依靠能够创造真正价值的出色作品,即能够迎合所有用户的游戏,而不只是0.004%的鲸鱼玩家。

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4,篇目5(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或者咨询微信zhengjintiao)

篇目1,How to Keep People Playing Your Game

by Jennifer June

So you’ve released your game. Congratulations! It’s finally out there for everyone to enjoy and the downloads will roll in. If you build it, they will come. Right? All the way from Brazil, Sabrina Carmona of Square Enix Latin America graced the Ottawa International Game Conference (OIGC) with her presence to talk to industry hopefuls and seasoned veterans alike about what it takes to keep your game alive and kicking after release.

In order to reach the top 10 free apps on the App Store in the US, you need to reach approximately 70,000 downloads/day. As if this weren’t enough of a challenge, most players delete games after downloading them. Carmona’s “first-date” metaphor was very appropriate here: how do you intrigue your date enough for a second-date? How do you make the relationship last? “How do you get lucky?”, she asked the audience with a coy smile.

User Acquisition – Ask them out.

Carmona described three types of user acquisition: organic, paid, and extra. Organic growth can be described as acquiring users based on methods that cost little to no money to execute, such as a stunning app icon, intriguing screenshots, a good video or trailer, an interesting game description, good reviews and fitting keywords. If executed properly, you can gain some serious traffic while giving your wallet a break. Alternatively, paid methods, such as burst campaigns, cross-promotions and email marketing can become expensive, but are often well worth it.

And then, there’s that extra effort. This, explains Carmona, is where you can truly make your game shine and distinguish itself from all of the other games out there. Doing something out of the norm with social media (outside the realm of Facebook and Twitter), having a unique press release or getting on some key app review sites can really give your game the extra love that it needs and well, deserves.

User Engagement – Get a second date.

Now that you’ve got yourself some players, you have to figure out how to keep them interested. Figuring out who is playing your game through analytics is one of the most important aspects of effective user engagement. “Who is playing your game? How do we cater to them?” asked Carmona. It is this information that will prove to be vitally important in your user engagement methods, such as events and updates.

To demonstrate effective execution of events, Sabrina referenced mobile game legend Puzzles and Dragons, which was the first mobile game to hit $1 billion in revenue. The game has mastered the use of events to keep users engaged and to turn casual gamers into mid-core gamers (Carmona defines these players as those who schedule gameplay around their lives). Events can be seasonal (“Christmas is here!”), limited time offers (“You better hurry!”), scheduled (“Only on Tuesdays!”) or involve social media (“Share this post!”). Each type is extremely effective in tapping into that user psychology, that voice inside that says, “I better open this game again.”

Updates are also extremely effective in enticing your user base to come back to your game, explains Carmona. A common mistake is putting all of your awesome content out at once, so don’t give it up so easily; make them crave it. Leak out your new content and new features slowly to build excitement among your players.

User Retention – Keep them wanting more.

Two of the best ways to keep your users coming back to your game are through push notifications and heeding user feedback. The “smart” way to do push notifications, according to Carmona, is by targeting niched casual players of your game so as not to annoy your loyal players that you’ve already won over.

Providing an effective support service can go a really long way as well, though it is necessary to prioritize users who are spending money when dealing with high volumes of user feedback. Always make sure to keep any complaints contained (especially over social media) with fervent apologies and reassurance. When users provide feedback, say thank you! And when they come up with a good idea for your game, implement it!

User Monetization – Get lucky.

And now the age old question in mobile games: how do you get your users to pay? Carmona explained that mastering the art of sales seduction is paramount when it comes to ringing in those sought after microtransactions.

One way to accomplish this is by effectively conveying the value of purchase; users need to feel like they are truly gaining something from the transaction that will make their lives easier. A great way to achieve this is by timing the opportunities to buy by offering your players a power-up or item right when it might come in particularly handy. Of course, you must always teach your players how to spend their money (a tutorial must-have).

So even though you’ve proven how awesome you are by finally getting your game out there (really awesome by the way), you might want to implement a few of these tips and tricks to make sure that your mobile game stays relevant in that oh-so-saturated market. Keep enough people coming back for more, and you just may be on your way to hitting that 70,000/day mark. See you in the top 10!

篇目2,How to keep players playing – Long-term Retention

by Mikkel Faurholm

Long-term retention is one of the most important factors of releasing to the AppStore and Google Play. With that many F2P titles a game needs to initially hook the player and make the engaged about whatever the story/theme might be. A very underestimated long-term retention strategy is to engage player by creating a vision of what the player might become if some time, and possibly some money, is put into the game. Some games tries to engage through a dramatic back story and a ‘helper’ that the player hopefully sympathizes with and take on the task as the new ruler in this playful environment. This is especially present in the strategy/builders targeting adults like the ones listed below.

The problem with this type of engagement strategy is that the player seldom interacts with the ‘helper’, leaving this working only as an initial hook and not long-term. At some point this helper becomes like Office Assistant Clippy from MS Word in 1997 and it actually ends up working against the intended purpose.

To heighten the likelihood of engaging a player long term, the game needs to create a vision for the player. Visualize the goal, what the player can become, and what awesome features are ahead. People are terrible at creating these visions themselves. Most people cannot see passed what it in front of them right now. It is the same reason that rearranging furniture will help you sell your house. The furniture are still not going to be there when the buyer moves in, but by rearranging your furniture you’ve successfully created a vision that the buyer can process. enough real estate though.

There are some great examples of games where this vision is presented effectively and feasible to the player – and then there are some examples of games absolutely failing at doing so.

Let’s start with the good

Supercell’s Hay Day introduces your neighbor, Greg, in the very beginning of the game, and while Greg just like in the examples above, seem like a nice and helpful fellow, he is sure to annoy the hay out of you by the time the first boat arrives. But Hay Day and at the time friendly Greg does one very clever thing before releasing the player out into the wonderful life as a farmer – show you Greg’s farm. Instantly the player is introduced to what is possible within the game, what the player has in store. This is a brilliant way to engage a player long term, wanting the same as his/her dear neighbor.

Mooving on to another great example, surprisingly also from Supercell. you guessed it. Clash of Clans. Clash of Clans ultimately does the same thing, though in a different way. Here you have the same initial hook through the very nice lady telling you quickly build a cannon before it is to late. (A monetization strategy which is most likely going to have a post of its own)

But quickly you are introduced to one of the main mechanics, namely attacking other player and earning ranking points to climb the leaderboard. In the leaderboards menu, there are the ‘top clans’ and ‘top players’ tabs that the player can investigate – and this is the brilliant part. Here you are introduced to real players, not a Greg, who’s village look like this:

Compared to the initial village any player starts out with, the one above looks pretty damn cool. Creating the vision!

Ok, before this turns into a post about how Supercell can’t do anything wrong, let’s have a look at some of the games that failed to do this, and paid for it.

Similarly to Clash of Clans, Dungeon Keeper introduces raiding in the campaign and attacking other player fairly quick, enabling the long-term engage, the carrot at the end of the dungeon, through other player’s awesomeness. The Screenshot on the left is myself after ~1 hour of gameplay. The one on the right is the leading player in the world. The difference is there surely, but not creating that vision and the long term engage. Do I want to spend hours and hours to get the dungeon on the right? not likely!

Another common misconception is that the end game, the final boss, should be concealed and not spoiled to the players. This might be how the players of video games in the 80s and 90s would want it to be, but it isn’t the case with the casual gamer. If a player cannot see where his/her time is going, the next free game might seem just as interesting, ’cause who knows whats around the corner. Games targeting the casual player needs to show whats around that corner. SO essential in order to create that vision.

Why do you think you are able to scroll all the way to the end of Candy Land in Candy Crush Saga?

People have no need for unlocking worlds like in the classic platformers. Show players the entire path to the end product and they are much more likely to keep on playing and maybe even throw in a dime or two to get there.

Engage your player, through gameplay, through fun mechanics and social features. But remember to keep them engaged by painting that picture for them, show them whats behind the next corner and create that vision.

What do you think? What makes you play the game over and over again? Is the ‘long-term vision’ important to you in a F2P game?

篇目3,How Multiplayer and Events unlock higher retention and monetization in mobile games

by Gabriel Cornish

With competition in the mobile games market rising, success has become unstable; obtaining a place at the top of the charts no longer guarantees months of high revenue. With the steady influx of new, high-quality games being created, even the most popular games are seeing large portions of their player base leave, and faster than ever before. As a result, retention rates have sunk for all but the most successful games, dragging monetization rates and lifetime value down with them.

A proven method for increasing retention rates on mobile games is multiplayer features. Single player games are starting to lose steam in today’s market due to their limitations: their gameplay is either repeated ad nauseum or finite based on content length. Most mobile single player games only retain a player long enough to beat the game or grow tired of it’s core gameplay mechanic. Multiplayer provides the player with a feature that stimulates a desire for gameplay by making it more competitive and social. Some mobile games have seen multiplayer add another 50-100 hours to the game’s lifespan.

Multiplayer brings a social atmosphere that takes gameplay to a new level of intensity and excitement. With the teamwork and competition brought into the game, players are inclined to play more intensely, more often, and for longer sessions. Furthermore, players have incentive to introduce their peers to the game to compete against them, creating a free, high quality acquisition channel. Social gaming brings together strangers over a common interest, creating new connections and forming a community around the game.

Multiplayer adds a new dimension of gameplay that establishes invested players, who are more likely to generate revenue and are less prone to quitting. For example, in War Metal: Tyrant, players who are in clans have an ARPU 20 times higher than those who aren’t, with 55% of Tyrant’s revenue coming from the 6% of players that are in clans. And which players do you think play more and stick with the game?

Multiplayer itself can be further improved through live events such as tournaments. Tournaments foster a competitive atmosphere bracketed by a time limit. The immediacy of the competition increases in-app purchase likelihood and enhances gameplay to provide a more rewarding experience. The break in monotony becomes a refreshing experience for gamers and also can work together with seasonal content to keep the game feeling fresh. Real and virtual prizes can be set for the winners of the tournament, giving a strong incentive to participate and play more matches, especially if the tournament is based on number of wins rather than high score.

As you can see, developers should aim for quadrant I on the chart if they’re looking to maximize their user loyalty. In this quadrant we see the highest amount of 90-day retention and the frequency of use. What multiplayer and tournaments end up doing is taking a regular arcade game, which is most likely located in Quadrants II-IV in the shown graph, and transforming it into a social turn-based game found in Quadrant I. As shown in the graph, Quadrant I is the most ideal place to be, with both a high frequency of use and a high retention rate for its games, and is the home of popular apps such as Temple Run and Angry Birds. There is no doubt that multiplayer and tournaments significantly help a game reach that stage.

篇目4,Exploring New Content and Player Retention Theory

by Alexander Engel

In one of my other lives, I am a writer. Many nights I sit down on my laptop and bang away at the keyboard, writing about video games and whatever else comes to mind. Sometimes I’ll be up late at night writing, annoying my wife with the clacking, when I’ll have a burst of inspiration and start clacking even faster, much to her dismay. I got on this topic today and, since our players like when we go into the details of how we make games, I decided to share it with our players.

The question I was thinking about was, how do you compare the benefits of retaining new players versus creating content for older players? Please note that the rest of the blog post is theory-crafting, and doesn’t necessarily reflect how we (or any other game company) operates.

The answer is surprising difficult. The root of the question lies in how long the game remains enjoyable for our players. I took some time to think about this and came up with a simple equation to figure out how many days of playing an average player will take to exhaust all of the content in the game, at which point they have nothing left to do and will churn out:

((H + C + X) * E) / P = L

Where H are the hours of content produced per week, C is the content already in the game, and X are the hours of player-to-player content engaged in per week. Multiplied by the number of weeks the game has been out (E) and divided by the average playtime per day in hours (P) you can come up with a rough idea of how many average days it will take for content to be exhausted for the average player. Finding those variables, however, is where the difficulty comes in.

To find the amount of content per week, we need to look at a couple of other variables: Bandwidth (D), which are the amount of hours per week the team can dedicate to the game; Bugfixing (B), which are the amount of hours per week the team dedicates to bugfixing per week; Project Hours (J), the number of hours the team dedicates to projects per week (performance, other platforms, metrics, shop, etc.); And how many hours of bandwidth it takes to produce a single hour of game content (K). Put that way, the formula for H becomes:

(D – (B + J)) / K = H

To find the amount of player to player activity an average player engages in per week, the formula is a bit simpler. You take the total number of players engaged in PtP per week (A), multiply it by the average amount of time they spend on PtP per week (B), and divide that by the total number of players that logged in that week (D). You end up with this formula for X:

(A * B) / D = X

So to test this formula,let’s assign some variables to each. I have taken the liberty to assign completely random numbers to this formula, which do not reflect our actual work or time spent in any way.Instead,pretend that they are for an imaginary game called Space Cowboys that I magicked into creation last night.

After being broken out, our final formula looks like this:

((((D – (B + J)) / K) / E) + (((A * B) / D) * E) + C) / P = L

Remember, this imaginary game was released 180 days ago and is called Space Cowboys. We have been tracking our Space Cowboys player numbers, and we can plug them into our formula. With these completely arbitrary numbers we can get a result:

((((180 – (120 + 40)) / 8) * 10) + (((200000 * 5) / 300000) * 10) + 100) / 2 = 91

Yes, I know my math and formulas are messy and not ideal.

So the final result is that, on average, after our arbitrary game has been out for ten weeks, our arbitrary players will exhaust all content after 91 days of gameplay. This assumes an average playtime of 2 hours per day and 5 hours of new content published per week, with ? of our players engaging in PtP play for an average of 5 hours per week, and 300,000 weekly players. This also assumes that we stop making content after 10 weeks and that players stop doing PtP after ten weeks.

But wait, there’s more! We forgot something vitally important: Not all players will play indefinitely until all content is exhausted. Instead, many players will become fatigued and churn out at some point in the game. In fact, for the vast majority of games, a huge percentage churn out after signing up and never play the game at all. So for our imaginary game, let’s set up some imaginary churn rates for an imaginary 1,000,000 players that signed up on Day 0, our launch day.

Day 0 – Retention Rate: 100% – Players: 1,000,000

Day 1 – Retention Rate: 75% – Players: 750,000

Day 15 – Retention Rate: 50% – Players: 500,000

Day 30 – Retention Rate: 40% – Players: 400,000

Day 90 – Retention Rate: 25% – Players: 250,000

So what our first formula established was the average time for players to run out of content. What we also have to determine are how many of our imaginary players will even be playing by the time they hit that wall. Using the numbers above, we can expect that at day 90, we will have 250,000 players playing our game. At that time, the average player will have run out of content, meaning that 125,000 of those players will have nothing to do. The other 125,000 will have something new to do, but how much will vary.

Put together, the chart of “Engaged Players,” i.e. the players who have not churned out and still have content to do, begins to look something like this for our numbers:

So by Day 180, we could expect Space Cowboys to have 100,000 remaining players, except since we stopped making content on Week 10, and since they stopped playing PtP, they all exhausted the available content and now we have no one left who wants to play our game. Looking at the graph, we really start to see the effects as early as Day 90, since by then many players will have churned out, and others will have completed content. We could have changed this if we’d either built more content, increased the retention of our players, or acquired new players.

So we need to add something more to the table: The incoming numbers of new players who start out, effectively, at Day 0 every time we acquire them and have them start playing our game. To show this, I added two more player cohorts into the mix, with a cohort of 500,000 players acquired on Launch Day + 15 and another cohort of 250,000 players acquired on Launch day + 30. That changes the mix substantially, because we have the cohort of 500,000 players effectively starting at Day 0 on Day 15 of our initial batch of 1,000,000 players, and another cohort of 250,000 players starting at Day 0 on Day 30 of our initial batch, and day 15 of our second cohort. The end result is this:

Still pretty grim. By day 180, even though we increased the total number of players by 75%, we end up with only a tiny fraction still playing the game. So what can we do, as a game developer, to stop that? Well, we could change our retention rate. If we found a way to boost our retention rate by 5% at every step, we would have a boost in players playing our game before they exhaust content:

By days 15 and 30, we would have around 100,000 more players playing Space Cowboys. Not too bad for boosting our retention rate up 5%. However, we still end up churning out players by Day 180 because they ran out of content. If we changed that and doubled our content, pushing our exhaustion date out to 180 days, yet kept our retention rate the same, we would see a greater improvement:

By Day 180, we have almost tripled the number of players still playing. The total number of players, however is still low. This brings up a limitation of my graph, because I only extended it out to Day 180. We’ll see a long tail of players that will continue playing after day 180 which should be substantially longer than the Base or Retention model. This model seems like a slam dunk, but the biggest problem here is that content is expensive. Doubling our content in the game would require many, many hours of work and a much larger team. Our numbers above posited that 8 hours of development work was needed for one hour of content. That means for doubling the existing content in the game – from 100 hours of Space Cowboys to 200 hours of Space Cowboys – we would need 800 hours of development time. That time would go to new art, new engineering work, new design, implementation, QA testing, and regression to make sure we didn’t break any of our existing game content too badly.

I’d like to note here that creating more content isn’t a faucet that you can just turn on and off. Not everyone at Disruptor Beam can equally apply their skills everywhere. I am not too good at creating game systems or coding, and some of our engineers would probably run away screaming if I asked them to take support tickets. Hiring people to do additional work also takes plenty of time. From the hiring process, to interviews, resumes, and other legal work, it can take some time to find a candidate. After that comes the lead time before they can begin, and then they have to be trained before they can dig into the issues. That lead time may vary from a few weeks to a few months, so even doubling team size may not show benefits until (sometimes) several months later.

Anyway, back to Space Cowboys. The final numbers comparing the approaches look like this:

We have to balance increasing the stickiness of a game, meaning the rate at which players are retained, especially during those beginning days, and the rate at which we produce content. At some point, most of your original players have churned out, but you also have the opportunity to reacquire them through further updates, expansions, and changes. Keep in mind that while creating content is very expensive, acquiring customers can also be quite expensive. We have to balance the cost of each with the benefit it provides.

Balancing new players, retention, and new content is part of what separates a successful online game company from an unsuccessful one. Here at Disruptor Beam, we’re excited to take on this challenge for our players, so they can keep having fun within Westeros.

篇目5,Love your free players to unlock the full potential of free-to-play games

by Greg Richardson

It’s already clear that free-to-play games are having a profound impact on the industry landscape. Their initial success is in large part driven by the frictionless reach being free enables. By removing the need to pay up front, a game can reach an audience that’s as much as 10 to 25 times larger. Anyone who owns a smart mobile device or a PC with an Internet connection is now a prospective player.

But to catapult the growth for free-to-play games to truly massive audiences, a subtle – and perhaps counter-intuitive – design philosophy is required: Your game’s free players are actually more valuable than its biggest spenders. It is free players who hold the key to creating sticky communities, driving virality through word of mouth, and maximizing the opportunity for long-term engagement and monetization of your game service. If you want to avoid the headwinds that companies such as Zynga have run into in recent months and instead ride the tail winds that are driving Riot Games into a multi-billion dollar enterprise, you must learn to love your free players.

To date, most free-to-play game developers have eschewed free players and instead focused (at times myopically) on a handful of big spenders, known in the industry as whales. Whale-driven games are designed to create monetization friction early in a player’s life cycle. This culling process effectively eliminates 98 percent-plus of the new players in a game so that it can instead focus on diving deeply into the wallets of those remaining 2 percent of players who pay. Among that 2 percent, only a tiny fraction has the desire and ability to spend large sums of the money. So the breakdown in some games can become scarily skewed, with as much as 50 percent of the profits coming from 2 percent of the paying players – or just 0.0004 percent of the total audience.

As the free-to-play game market has evolved and the number of competitive whale-driven games has increased on both Facebook and smart mobile devices, an uncomfortable fact has settled on the industry. Despite the ability to reach billions of potential players, the number of whales with a desire to spend thousands of dollars is relatively tiny. Moreover, whales are not going to be able to spend huge amounts of money across multiple games at any given time. As a result, companies are seeing new whale-driven games perform worse than their predecessors, while also cannibalizing their own whales in existing games.

Contrary to popular belief

The truth is that players who choose not to pay anything are far more valuable to any game company looking to create sustained value for its shareholders. Here’s why:

The best free-to-play games are socially driven. The entertainment value of playing the game is either intrinsic to playing with other players or at the very least materially enhanced. By designing your game to compel free players to stick around for a long period of time, you create social stickiness that will result in a higher retention of your paying users. This is common sense. Who wants to save for months to buy that shiny new BMW if there are no friends or neighbors to admire it?

Moreover, free players are by far your best means of low-cost, high-quality player acquisition. Free players who enjoy the game are viral in the old-fashioned sense: They actually tell their friends to try the game because they enjoyed it. Instead of paying for 50 percent of your new users and then watching them churn out in a week, design your game to ensure free users enjoy it and watch your cost of player acquisition drop dramatically.

And it’s a funny thing about those free users: the longer they play any free-to-play game, the more likely they are to convert to paying players. The cohort of free players who continue to be actively playing a new game for a month are nearly three times as likely to convert as new users you paid to acquire. The financial advantages of focusing on free players are further enhanced when your game caters to a more diverse demographic and geographic player base. There are simply more players in the world who will happily spend $5, $10, or maybe even $25 on a game they love than there are those who are capable of spending thousands of dollars.

Games that get it right

It’s no surprise then that two most profitable free-to-play games currently in the market have eschewed whale-based monetization. League of Legends from Riot Games and World of Tanks form WarGaming.net decided to focus their game design and monetization efforts with a long-term view of value creation, which prioritized the free players.

Unlike their Moby Dick-obsessed competitors, LoL and WoT are designed to convert a far higher percentage of their players – in some cases ten times as many players as a whale-driven game. Instead of designing the game to optimize for a handful of big spenders, they’ve created economies that allow players to incrementally spend in lockstep with the time they spend in the game, which has resulted in higher retention, effective word-of-mouth virality, and a higher median lifetime value of players.

Both League of Legends and World of Tanks made a conscious decision not to force players into “purchase or else” decisions early in the game. Their pricing and merchandising systems are optimized for consistent small- and medium-sized transactions instead of a handful of big-ticket items. They thoughtfully open the vast majority of the game’s experiences to a free user while making sure value is delivered when a player makes the decision to pay. Thus, a virtuous cycle is born.

Happy free players lower overall acquisition costs, while paying players feel a stronger relative bump for their decision to spend. And all players are compelled to keep playing with one another, as there are plenty of teammates and opponents to fuel the multiplayer and social dynamics of the experience. That leads to higher retention; with higher retention comes higher conversion to paying, higher spending, and ultimately higher profits.

There are challenges in designing games to achieve those goals. Basing your monetization systems off the game mechanics that generate real fun is the starting place. Inspiring players to make themselves unique or benevolent in the eyes of fellow players are great incentives — while frustrating them by designing the game to be enjoyable only when you pay is not. Don’t force failure for free players and make sure the forks you create with opportunities to pay come with a balanced frequency, and not as hard walls.

The opportunity for the free-to-play game space to grow is limitless. With browsers, smart phones, tablets, and Facebook, the digital reach of games is quickly going to reach a number closely approximating the entire population of this planet. The realization of this opportunity is going to be driven by great products that create real value, products that are designed and managed to entertain 100 percent of their players – not just the 0.0004 percent known as whales.

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号