数万字长文,从电影制作角度比照看游戏的设定思路,下篇

从电影制作角度比照看游戏的设定思路上篇,非常正面,谈到了电影制作对游戏设定的一些启发性(三篇都是大长文)。

下篇就会从一些更简短但偏负面一些的角度来阐述游戏和电影本身的一些鸿沟(虽然有些分析,实在是相当不理想,但也是列举出来权做辅助阅读)。

篇目1,分析电影、书籍与电子游戏的媒介特性与区别

我们很容易就能猜到为什么大多数人认为作为媒介,电子游戏同电影如此接近:两者都是通过图像表达它们的故事。

我的确相信电子游戏是故事媒介(游戏邦注:此分析并不适用于大部分无需故事情节的游戏),比起电影,我们认为电子游戏更类似书籍。为了证明我的观点,我将从特定的角度分析各种媒介的主要特点。

长度:故事发展需历经多长时间?

电影基本上为短时媒介。大多数电影时长为1.5个小时,也有些电影可能是2小时、3小时,极少有电影长达4小时之久。基本上,只需一个下午或一个晚上的时间,你就可以欣赏完整部电影。

另一方面,书籍需消磨更长的时间。而这取决于书本的页数和读者的阅读速度,但我们一致认为,大多数情况下,只需1-2周左右的时间便可读完一本书。当然,你也会偶然碰上一本好书,然后在几个小时内读完整部著作,但这并非正常情况。

电子游戏也是同样原理。通常,我需要1-2周的时间完成一款游戏的所有关卡,但是如果让我碰上一款出色的游戏,那我一天之内便可通关,虽然这是少数情况。

电影时长较短。所以你必须加快情节的发展,删掉那些完全没有必要的情节。电影的简介极少超过20分钟,你不能在情节中设置过多迂回曲折的故事。这也是为何大多数的电影只讲述非常简单且直白的故事,否则传递过多信息会导致观众数量快速流失。

只要与书籍或电影相关,你就觉得自己有很多时间。有些书会多达2000至3000页,而有些游戏可持续60多个小时的体验时间,甚至更多。通常这些媒介具有5-10个主要角色,它们都有自己的发展特性及发展历史——而电影却没有。

事情可以更慢发生,简介的时长也可以延长。显然,你也不想拥有长达1小时的简介画面,而你可以在进入真正行动前提供1小时,可能2小时的“开场白”。比如《Fire Emblem: Path of Radiance》中:真实情节并未在第四个任务前上演,而大多数的玩家已经在游戏中耗费了1或2个小时了。

同样,媒介的长度会大幅度地影响故事的节奏。

节奏:故事的节奏如何?

因为我们通常都是无中断地连续观看电影,所以大多数的电影都遵循同样的节奏:能够吸引观众的强有力的开篇形式(游戏邦注:通常与主要情节无关,或者只在中间涉及一些,或者穿插于整部影片中),接着慢慢引入主角及情境,接着故事情节开始发展,达到高潮然后结束。

另一方面,我们可以在书籍和电子游戏中享受更长的时间,而每次阅读或体验后会进行长时的休息。这也是为何这里的故事需以不同节奏发展。

你仍然可以慢慢构造一个大型的主要情节,直到达到高潮,然而故事发展一段时间后,只有少数观众欣赏时,你要另外组织更小更复杂的故事。书籍和电子游戏都以章节形式存在。而游戏中的分节并不明显,但是每款游戏都设有关卡、地牢、任务、过关模式……每个章节实际上又包含了一个次要情节,其中的小高潮及悬念能确保读者/玩家继续体验下一章节。

这就促使你将故事分成更小的组块,借此发展次要情节,丰富主要故事的发展。你甚至可以为每个章节搭配一个特殊角色,相较于电影,你可以决定它们的发展。

对话:信息是如何被转达的?

在电影中,任何事物都依赖于电影所呈现和讲述的事物。你可以利用一些文字(比如某地名,或者显示在屏幕上的一些信息)。当然有些例外,比如标志性的《星球大战》介绍,但它们本身就是个例外。

对话必须简短,因为观众无法跟上太长的对话。电影中不要设置过多独白,越简单越好。同时,电影大多依赖于演员的表演,以及他们如何生动地传达出情感。

另一方面,书籍依赖于文本。书籍记录下所有事物,包括每句对话台词和每个描述。当两个主角在交谈的时候,读者可以自由想象他们当时的态度、情感等等。

而在电子游戏中,由于科技发展,大多数的游戏都有配音效果。但大多数重要的数据仍通过文本传送。然而游戏中的演技十分有限,只有一些塑造精良的角色可以传达真实情感。

super-mario-galaxy(from techi.com)

想象:需要留下多少想象的空间呢?

电影没有留下过多的想象空间。它向观众呈现出每个地方/行动的具体细节。

另一方面,书籍很少描述所有事物。它需要读者自己的理解。

游戏也是如此。许多游戏允许你定义自己的角色,除此以外,你可以自己决定事情的开端。游戏或者书籍只会告诉你:他同时与10个敌人作战,并打败了他们,这需要读者去想象战斗场面,而玩家需参加真实的战斗。

电影因其属性的原因不能脱离现实。你不能让场景看起来过于虚幻,否则就会出现明显的电脑制作痕迹。你不能让主角看起来与人类大相径庭,否则你将无法找到相匹配的演员。当然,你仍可以从事动画电影制作,但这意味着你的观众是特定群体(指孩子)。

在书籍和游戏中,你可以想象自己想要的任何事物,并创造出来。在书中,读者可以自由进行想象,在游戏中,由于所有事物都是虚拟的,即使场景看起来并不真实那也没有关系。

续集:重点是什么?

电影领域极少出现续集。你需要聘请相同演员,而且情节需要与第一部电影紧密联系。而且你会纠结于演员变老这一事实,所以如果你在15年后才开拍续作,你最好能想出15年后的故事情节(当然,你也可以使用化妆术让演员看起来更加年轻或者更加年迈,但只是从某种程度上考虑)。而且观众常常会将电影同他的主角紧密结合起来,这意味着演员在真实生活中也是此种状态。

书籍和游戏在续作方面比较不会受限,它们并不要求坚持相同的角色(续作发生的时间不会被时间发展顺序所束缚)。我想这也是为何这两种媒介会出现大量续作的原因。你不必坚持某个角色:因为这些故事并不过多依赖演员的脸庞和表演,你可以转变读者/玩家的关注元素。

因此,我希望你可以从上述讨论中获取某些信息,实际上,这有助于你在这一新兴媒介中塑造出独具特色的呈现故事的方法与工具。

篇目2,阐述游戏想法与电影之间的渊源和区别

游戏想法源于何处呢?你不能将游戏视同电影,因为所有电影之间的相似度要高于游戏。但电影只是个故事,而游戏是种体验(游戏邦注:行业专栏作家James Leach曾指出,机制才是主导,故事只能居于次席)。

很少见到单个人声称自己有个游戏想法,而那些只有架空概念的人也往往不会受到他人的注意。不久之前,有个粉丝在某个展会上拦住了Peter Molyneux,告诉他说自己有个很棒的游戏想法。Molyneux回答道,他自己也有个很棒的绘画想法。从某种程度上来说,这是个很棒的回应,想法几乎是毫无价值的。你可以在早餐之前的那段时间内想出6个令人惊奇的游戏叙事概念。

新游戏开发背后的想法往往以机制为基础。看看《小小大星球》,这款游戏并没有具体的内容,但是这个令人满意的世界中可以玩出许多种故事和体验。

games ideas & films(from next-gen)

行业内的创意文案通常会对如何在游戏开发后期添加故事、情节和叙事结构大感困惑。但是如果游戏是围绕玩家能够做的事情来构建,那么这种情况时常会出现。尽管如此,如果故事的插入时间不算过晚,那么就不会产生问题。虽然这不会导致故事在开发过程中不断改变,但是在游戏中,故事并不是最为重要的。

那么,如果机制和游戏玩法是最为重要的话,为何会出现如此多类似于电影的游戏呢?项目开发启动之后,游戏设计通常也总是会从电影和电视中寻求灵感。如果每个程序员和设计师都会看科幻片,每个艺术师都很喜欢漫画和超级英雄的话,这种情况是很正常的。开发者全身心投入到自己最喜欢的题材中,在第二天的工作中就会决定执行他们前天晚上看到的东西,这已经是个传统。

事实证明,这种做法并没有什么不妥。如果我们没有看过《黑客帝国》的话,那么《英雄本色》的“子弹时间”(游戏邦注:这是指游戏中的“慢动作”,玩家发动攻击时候,时间会慢下来,方便玩家做出各种动作和瞄准)。如何能够发挥作用?如果没有詹姆斯·卡梅隆电影《异形》的话,我们还会觉得《星际争霸》中的女宇航员那么酷吗?受《异形》影响的游戏非常多。如果玩家一开始就能够理解其中的世界,那么他们也会更容易融入游戏。通过电影,所有人都知道了爆炸、海啸和火球,所以我们在相同的起跑线上。

现在,像半兽人之类的元素已经为人们所共知,游戏已经不需要对它们进行解释。就像瞄准镜或激光一样,我们对此类的东西完全熟悉。但是,这类熟悉也会带来问题。

首先,游戏需要处理其中涉及的正义性问题。其次,事情有其一定的年份。讽刺的是,想法越具有原创性,就越不容易为人们所接受。之前提到的“子弹时间”便是个例子。第三,借鉴概念和单纯的抄袭之间有明确的界限。如果Lara Croft是个戴着帽子的中年男人,那么情况可能就会有所不同了。

借鉴自电影的不只是武器和角色,电影术和情节也是如此。比如,过场动画就需要依附于电影原则。同样,情节和故事也通常会追踪三幕结构和主人公的旅程。这些规则之所以存在,是因为它们能够产生作用。当然,某些很棒的电影会改变甚至打破这些规则,并利用这种做法体现价值。但是,这种事情不会在游戏中发生,原因有两点:首先,精巧的故事讲述和情节操控不可能将普通游戏转变成游戏巨作。记住,游戏的侧重点不是故事。其次,游戏不只是线性化的体验。

随着游戏越来越像电影,它们逐渐模仿并有可能被电影惯例所牵绊。你只能被已经存在的东西所影响,所以你总是会慢一拍。当新技术在3D电影中显现时,你可以将其运用到游戏中。或许这会被称为抄袭,但是你需要做的就是进行模仿,你可以将其称为对电影的致敬。就像最近的游戏《黑色洛城》一样自豪地庆祝其上世纪40和50年代的电影鼻祖。

有时我们得到的是开发者想要制作的游戏,有时游戏或许是他们想要制作的电影。如果能够取得成功固然好,可以算是锦上添花。但是如果故事、主题和游戏玩法无法恰当配合的话,那么游戏就将面临失败的危险。

3,GTAV团队谈游戏设计为何不同于电影制作

Rockstar Games游戏《侠盗猎车手5》(以下简称GTAV)预算超过1亿美元,发布之初一天内的销售额高达8亿美元,如此强劲的吸金能力足以令其所有2013年的热作相形见绌。但这款游戏大获商业成功的同时,也招至不少评批。该游戏是在2008年的《侠盗猎车手4》的基础上开发,这个新款游戏故事背景是虚构的Los Santos小镇,允许玩家在三种不同的角色间切换——银行抢劫犯Michael、Trevor以及他们的新同伙Franklin(一名重生的男人)。这个三人组合被迫参与一系列由FBI主导的滑稽事件。GTAV呈现了一个允许玩家超越主要故事情节,探索其中内容的巨大开放世界。

Grand Theft Auto V(from indiewire)

在9月份于林肯中心电影协会举办的纽约电影节上,Rockstar开发团队的数名关键人物出席了由Revision 3 Games制作人以及电视主持人Adam Sessler主持的对话活动,分享了团队创造GTAV世界的挑战。他们从游戏玩家解救摩天大楼中的一名人质开始切入,该操作包括驾驶直升机,参与近距离的枪战,在马路对面狙击坏蛋,在逃跑过程中击落其他直升机。

这一幕完美呈现了游戏极快的节奏,从直升机所滑翔过的地势可见游戏世界规模之大。讨论小组在此较少关注故事情节,主要着力于围绕其中的游戏环境。参与讨论的成员包括Rockstar联合创始人Dan Houser、发行及运营副总裁Jennifer Kolbe,美术总监Rob Nelson以及联合编剧Lazlow Jones(他在游戏中也扮演了一个令人难忘的角色)。以下是本次座谈会的关键摘要,主要涉及游戏开发与电影制作流程之间的区别。

游戏设计并没有捷径。Rockstar极擅长创造“沙盒”,允许玩家自由漫游并体验游戏故事的巨大开放世界。GTAV中的Los Santos是该系列游戏中最大的一个城市,其规模是之前游戏版本中的Liberty City的两倍。每一个街角都是重新创造而成。这正是它为何要投入比一般传统电影制作更多年的时间开发这些游戏的原因。Kolbe表示,“如果是拍电影,你可以去任何地方取景。但如果是游戏,就得重头做起。”

游戏设计师的最大挑战?要创造三个(而不只一个)主角。Houser称在不打断游戏现实时间流的情况下切换角色之间的前景,在几个月之前对开发者来说仍是一个大问题。他说明道,“我们原先打算从纯故事角度入手,之后发现这只能发生于执行任务期间,但我们从非故事角度来看时确实更先进了一步。”

因为游戏如此庞大,所以并不能像电影一样从头到尾地通关。玩家有可能主要与故事互动,并不探索游戏世界,但这也需要他们耗时40个小时才能完成游戏中所有的任务。这一点与90分钟的电影截然不同。Houser称“我们并不采用电影式的叙事框架。”他称他们参考的是观看电视剧和小说的方法。这也产生了一个挑战:“在游戏中,我们并不知道你何时需要停止,人们有可能会忘记之前的进展。”

游戏中的确具有出色的演技。GTAV还使用了动作捕捉技术,该技术已经十分先进,甚至连美术总监Rob Nelson都表示即使是演员的独特步态在游戏中都清晰可辨。角色的面部表情也同样细节丰富,因为该技术可发现演员戴着佩有灯头照亮其面孔的头盔,并捕捉到每个细节表情。Nelson称这一过程是“戏剧与终极特定镜头的混合体”。

媒体讽刺也是游戏设计的一部分。任何玩过GTA某款游戏的人都很熟悉该游戏世界拙劣地模仿媒体对暴力事件的报道方式。联合编剧Jones表示,“模仿美国疯狂的消费主义是一件趣事。”但真正的讽刺却超越了故事本身:设计师创造了无数呈现在游戏中的虚假广告内容,以及不同广播电台的音频。编剧称他们听到有玩家反馈他们在游戏中曾将车开到路边并开始收听广播,现在你可以看到自己的角色在家里看电视。Houser称“我们努力为玩家引进一个与现实无缝隙的世界,让媒体进入游戏中的大街小巷,这更像是一种美国文化而不仅仅是美国。这正是我们着力探索的方向。”

4,游戏应该避免盲目地模仿电影

著名游戏策划师Warren Spector指出,在结构和叙述方面,游戏经常借鉴其他媒体,但我们必须重新考虑这种模仿了—-我们往往所关注的是应该向其他媒体学习什么,而忽略了不应该学习什么。

Spector表示:“摆在我们眼前的是各种诱惑,但是如果我们能够轻松地成为一种媒体,那么发展之路必会受到阻隔。模仿似乎是一件理所当然的事,甚至是任何媒体在发展过程中的必经阶段。在其他媒体打下的基础上成长,实在是正常又自然的。”

电影本身也是来自对戏剧的模仿。电子游戏比其他任何媒体提供了更多“故事叙述的构建材料”。他表示:“所以游戏怎么能不讲故事?当听到人们说‘游戏不应该讲故事’时,我经常感到困惑—-我认为这种说法既愚蠢又可笑。”

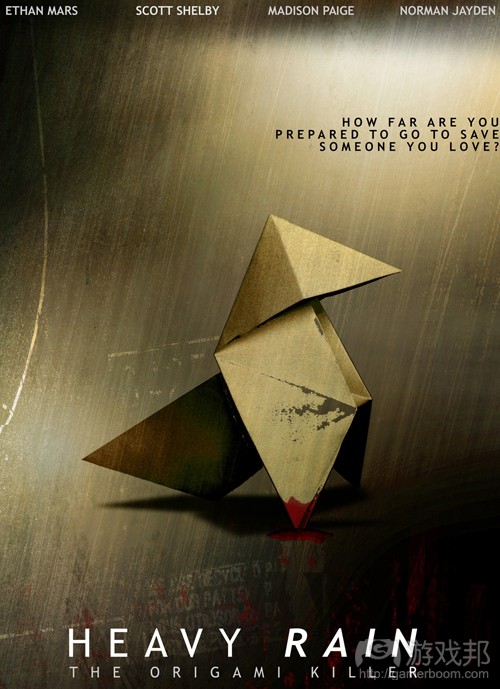

Heavy Rain(from reelloop)

但是游戏当然不只是“具有互动活动的电影”。“如果游戏只是其他媒体常规的混合物,那么我们就麻烦了。”游戏叙述当然还有更大的进步空间,甚至像《暴雨》这样以故事叙述为焦点的游戏也还没达到极致。

游戏和电影之间的共性就是在屏幕上移动的图象和与之配合的声音,从而创造生活中的同步幻象。在Spector看来,这一共性实在太明显了,几乎不值一提。

“从文化上讲,游戏与电影具有许多共同点;诞生于20世纪的电影改变了一切。正是因为电影,世界上的所有人才可能接收相同的文化信息。”

Spector表示:“我认为所有人都会同意,游戏已经超越了电影。”无视电影和游戏之间的“显著区别”是非常危险的。比如,主导电影体验的编辑技术和观众获知角色不知情的信息的方式,创造了一个结构,而那种结构在游戏中是行不通的。

“我们必须放弃一些‘显著区别’。那种‘区别’会破坏幻象,夺走玩家想成为自身经历的导演的体验。在大多数游戏中,拍摄活动是持续性的……我们要么控制拍摄本身,要么将拍摄权让给玩家。”

玩家不只是在看,同时也能够实时参与体验。“电影是非线性,而游戏则是线性的,并且要同时处理时间和空间。”

游戏的进展节奏也与电影不同。显然,电影的演出时间只是无尽的游戏时间中的一小片段。观众习惯于电影的惯例,但有时候,游戏开发者可以在不到一分钟时间内便吸引玩家的注意。

“如果你的游戏动作不够快,不能体现真正的动作性,或至少算得上吸引人,那么你的玩家就会离开。”对话方式必须是不同的,因为对话往往要重复利用。玩家可能在游戏中的相同区域停留相当一段时间:“你必须找到上百种方式说,‘我想我听到了一些事。’”而电影编剧在一瞬间就可以传达这种必要的体验。

游戏时刻也必须设计成可重复利用的。在镜头前飞过天空的鸽子,第一次看来非常棒—-但如果这种场面每一次都出现,那就显得很愚蠢了。让玩家制造他们自己的“魔法时刻”更有价值,而不是将这种任务交给视觉编辑技术。

游戏也仍然对自己的修辞负有责任—-受《龙与地下城》中的规范的困扰(游戏邦注“有谁想玩一款关于摇骰子的电子游戏?”)。Spector常常强调自己并不想成为“讨厌电影系游戏的家伙”。

但他认为在不使用其他媒体建立的成文惯例的情况下,我们还可以采取更多方法—-如研究AI除了战斗是否还有其他用途,或考察游戏专家和玩家在纸笔游戏中的呼唤和回应,以及更深入地理解为什么某些在电影中可行的技术在游戏中却毫无功效。

“我们现在面临的关键问题是,我们必须开始寻找什么才是突显游戏的东西。我们可以将玩家带到他们想象中的世界。游戏是人类历史上唯一能对玩家行为产生回应的媒体。其他媒体从未达到这样的程度。大概除了临场动作角色扮演游戏,不过它们不算。”

“在确立游戏的独特媒体身份的过程中,我们已经取得了很大的进步,借鉴其他媒体只能让我们实现一半的目标……但我们现在应该停止模仿了。我们需要一些原创精神。游戏作为一种媒体诞生已有30年了,你可以决定游戏的发展方向了,现在为时未晚。”

另外再补充两篇相对正向的分析。

篇目5,Massimo Guarini谈制作电影式剧情游戏的原因

有这么一代游戏玩家被开发商和发行商遗忘了。距他们第一次拿起游戏机时已经过去二三十年了,而现在,他们却再也没有时间或耐心享受像史诗一样冗长的RPG或甚至长达10小时的电影大片,但是,他们仍然对互动的、有故事的体验感兴趣。

至少,游戏和音乐制作公司ovosonico创始人Massimo Guarini(游戏邦注:Massimo Guarini是有14年从业经验的前Grasshopper公司创意总监,代表作有《暗影诅咒》和《火影忍者——一个忍者的崛起》)指出,整整一代的玩家没有得到游戏业的充分重视,因为游戏业把关注放在“努力吸引特定的人群,即15到20岁的玩家。”

他认为:“20年前玩《马里奥》或30年前玩《大金刚》的玩家再也没有和以前一样多的时间了。他们要带小孩,忙工作。他们早出晚归,他们疲惫,他们过着与15到20岁的孩子们完全不同的生活。”

“当你处于那种状态时,当你饭后和家人一起坐在沙发上时,如果给你两种选择,一部你知道会在两个小时内结束并且看过就作罢的电影,或你不知道要花多少时间付出多少努力才能完成的游戏,你要如何选择?基本上是因为太累了,所以,你会选择电影。”

社交和手机游戏开发商给玩家们的另一个选择是,玩那种一次只需短短几分钟的游戏。但Guarini认为,对于想拥有介于两者的体验的人,想要一款不错的叙事型游戏来消磨午后时光的人来说,他们几乎没有选择。

这就是为什么Guarini离开与之合作过《暗影诅咒》的Grasshopper公司,并在米兰建立新工作室后,想要制作一款类似于电影的游戏。他的打算是为那被遗忘的一代人、为没有多少闲暇时间的玩家和偏好不是“太空陆战队这类琐碎题材”的玩家做点什么。

故事型短篇游戏这个缺口,之后被越来越多独立的游戏开发者所填补,如Thatgamecompany出品的大作《旅程》和Plastic的迷幻网络实验《曼陀罗》,但玩家们真的想要这些浓缩版的游戏吗?

适量且易消化的游戏

尽管最近还有更多简短的游戏发布了,但在许多用户心目中,这类游戏仍然有污点,即游戏必须达到一定的时间限额才能挣到钱。如果游戏没有达到RPG或剧情游戏的某个长度要求,不见得玩家和甚至最狂热的媒体就会同情这个严重的缺陷。

Dan Pinchbeck是Thechineseroom创意总监,该公司最近发布了颇受好评的电脑游戏《Dear Esther》。他声称:“有些玩家欣然表态,他们不关心游戏的品质,一小时花多少钱才决定了游戏的价值。这个想法仍然让我感到吃惊。”

“我觉得这是完全不正常的。这就好比,吃饭时只关心能吃到多少食物而不理会食物是否美味。我不认为因份量大而为一堆垃圾花钱是值得的。”

说到游戏长度,在这场质与量的较量中,Pinchbeck并不是唯一心存不满的人。Gary Whitta是电影编剧(游戏邦注:Gary Whitta代表作是《The Book of Eli》)和Telltale的优秀插话游戏《行尸走肉》)的剧情顾问,他也抱怨大多数大型游戏的内容都是无意义的填料。

他还主张制作简短的“易消化的”游戏,不要把时间有限的玩家吓跑。Whitta拿食物作比:“如果你把一大盘子食物摆在我面前,就像让我玩《Skyrim》。我会说‘喔天呐,我怎么吃得完啊?’我想要的只是一盘美味的食物。适量就好。”

“可以这么说,适量的游戏就像吃一盘份量刚好的食物,觉得自己吃得很满足,刚好饱。你不会说,‘啊天啊,只因为我得把盘子弄干净,我就吃了这么多,真恶心。’”

改变期望和零售价

虽然是否存在一批渴望短篇游戏的玩家尚不明确,但玩家越来越欢迎和接受通过主机、电脑和智能手机等进行数字推广的游戏,这可以帮助开发商洗雪短篇游戏多年以来遭受的耻辱。

可下载的游戏往往是小游戏——因为预算紧张、平台对下载文件的大小设限,或各种其他原因——所以,许多玩家对短篇游戏有不同的期待,可能更易接受紧凑的游戏体验。

Guarini认为在这些下载平台上的游戏定价也经历了很长的时间,才让玩家接受了更简短但更便宜的游戏。他评论道:“你其实可以降低价格,因为你的产品没有多大成本,而当你搞零售时,使价格上涨的主要是成本。如果你将一款两个小时的游戏定价为60美元,这显然行不通。”

“你得和形式相似的娱乐方式竞争,比如蓝光碟的电影。要花多少钱,15美元还是20美元?我认为,那就是两小时游戏的价格区间。”(跟《旅程》一个价,有点小贵,而《Dear Esther》的售价是10美元,《行尸走肉》才5美元。)

要求玩家为一个短篇游戏花那么多钱,对开发商的压力更大了。Pinchbeck解释道:“我认为可能对有些人来说,花更少的钱买更短的游戏更冒险。如果你花60美元购买40小时的游戏,很有可能,至少在这40小时当中总有一些东西是不错的。如果你花10美元购买3小时的游戏,3个小时都得是精华才行。”

与此同时,只因游戏更短就降价那么多,这也很危险,因为玩家会认为游戏很贬值,他们在游戏上花的时间只值每小时1美元——结果,你可能会只投入每小时1美元的精力来做游戏。”

Pinchbeck还提道:“像《Dear Esther》这样的游戏需要大量的资金投入,才能提高制作品质。如果我们的游戏只标应用商店的价格,那我们绝对不会给它次世代的视觉效果。这是正常的契约——我们希望玩家支持创新,而我们也回报玩家创新的游戏体验。如果玩家只肯投入一点点,那也别怪开发商按那点预算设计游戏。”

大发行商没有信心

短篇游戏是否存在潜在受众,是否存在合适的系统让玩家玩上这类游戏,为什么没有更多大发行商尝试这种游戏?发行电影风格游戏的EA,和敢用游戏挑战夏季电影大片的动视,都不敢尝试这种游戏吗?

Guarini认为许多游戏制作商只是害怕尝试新事物,不敢制作比一般游戏更精炼的游戏,为玩家提供一种电影般的体验,而剧情又不只是射死坏蛋那么简单的游戏。

“我们确实对自己做的事没什么信心。特别是发行商,他们不相信能够在电子游戏中产生不同的类型。现在,这是一个比较新的行业。与电影的商业性和成熟度相比,我们还什么也不是。”

“所以,我们被迫认命,‘好吧,目前也只能达到这种程度了。我们只能做到这份上了,因为售价就是这样。’”

Pinchbeck指出,大型公司开发新的或还没成功的游戏类型成本较高,还要考虑到工具成本受限制。“如果你要大量投资这类游戏,你必须平衡开发投入和销售价值,而为了做到这点,你必须增加游戏的规模,才能达到那个销售价值。”

短篇游戏只讲节奏

对于那些决定开发电影长度的剧情游戏的开发商来说,他们要考虑的变数很多,很明显的一个就是,生产周期和开发时间会比传统的游戏短很多。

设计这类游戏时,更加强调节奏和密度。必须让玩家感到他们花在游戏上的每分每秒都很有趣很吸引人。再者,当玩家在短篇游戏上花的时间比在60美元40小时的游戏上多一小时,游戏中就不应存在任何可填塞内容的空间。

电影编剧Whitta认为,电影业在很早以前就学到,不要担心长度,只要把握节奏就好。尽管人们看似对两种媒体持有相反的期待,但他们往往推掉3个小时的电影,转而寻找那些要他们花上一周才能完成的游戏。当说到玩家是否能不顾长度地享受电影,节奏和密度起了很大作用。”

walking dead(from gamasutra)

能够成功地把握电影游戏节奏,同时让玩家从头到尾全身心投入,这样的游戏制作人得到的回报是现在大多数AAA游戏总监都得不到的:知道玩家更可能全程体验他们的游戏且不被打断时,游戏制作人会产生满足感,并欣赏他们的努力成果。

自由实验

因为开发预算少,生产周期短,开发商有更多机会实验他们的电影剧情游戏。不仅可以引入原创题材,还可以尝试新的叙述方式和完全不同于他们已经制作了多年的内容。

Guarini等着在年底展示Ovosonico的首款电影游戏。因为短篇电影游戏,他的工作室采用了非传统的团队组织方式——除了制作电影风格的游戏,他还像电影工作室那样,根据特定的项目雇用团队成员,而不是永远保持相同的员工。

“我认为拥有这个创意核心的秘密,主要是总监、制作人等内部人员。特别是,对于那些针对特定目标群体的短篇游戏。这意味着,如果你喜欢,你可以让游戏更个人化一点,更小众一点。”

Guarini表示,说这个实验什么时候结束,为时尚早。但他预言将来会有更多独立团队制作类似于短篇剧情的游戏。

篇目6,游戏可借鉴电影和电视制作经验优化产品

当我们在玩游戏时可能遇到过这种情况并常自问:“开发者到底是怎么想的?这种游戏有什么好玩的?”通常情况下,游戏并不是为你量身定做的,它也不是面向任何人的专属内容,开发者在游戏制作阶段并没有与目标用户达成共鸣。

最常见的原因是很多开发者并不清楚谁将玩自己的游戏。实际上,每个工作室都会猜测玩家可能喜欢的内容并以此去制作游戏,但多半都是在传达开发者自己的想法。

这也许是源于游戏产业的固有传统,即开发者一个人独自躲在卧室中开发游戏,并且只是制作自己想玩游戏。即使是现在的一些大型团队也同样如此,总是由工作室中的几个人去做出关键决定。但是他们的观点是否真的比其他人更加有效呢?

当然,我们都拥有经验,但是当提到设计一款成功的游戏时,我们真正需要的并不是观点,而是能够表明某一设计是否出色的证据。想出一个游戏理念固然是好事,但是你想提高游戏成功的可能性,你最好在发行前先对设计进行评估。这种创造性评估同样也会出现在其它娱乐产业中,但是不知怎么的,电子游戏却始终未把握其中要领。

电影

从1928年起,电影产业便通过试映方式去评估用户对于即将发行的电影的反应。制片人通过选定一些具有代表性的观众,并在他们面前播放完整的电影内容和可替换的结局。当出现片尾字幕时,观众便需要填问卷调查表,负责人也许会挑选一些观众进行面谈,或者导演将根据观众观看电影时的监测视频观察他们在不同时刻的反应。

这一过程是否能完善观众的电影体验?这一点毋庸置疑。许多电影通过改变演员,调整故事,为观众创造反应空间,创造紧张感或平衡用户关注水平等方法而得到完善。像《大白鲨》,《僵尸也疯狂》以及《惊变28天》等电影便是通过试映进行完善。《憨豆特工》的制作人便是通过试映而明确了主角出场的方式,所以他们重新设置了电影的开始阶段以解决这一问题,并有效地提高了测试分数。

通常情况下当导演基于试映结果再次编辑时,他们会惊讶地发现自己之前的编辑有多糟糕。即使是最老练的导演也承认自己的作品需要经过验证:Woody Allen(游戏邦注:美国电影导演,编辑,演员,喜剧演员,作家,音乐家与剧作家)便表示自己能够很轻松地写出一部剧本,但是只有在了解了观众对剧本的反应后他才清楚剧本的可行性。就像我之前所提到的,我们不能亲自验证自己的错误,不管是在电影产业中还是电子游戏开发领域。

电视

电视产业进一步实践了创造性评估过程,即在实时录像过程中进行喜剧材料的实时测试。我听说华纳兄弟的《生活大爆炸》便是使用这种方法去创造最佳结果。即在录制了一段场景后导演会对观众说演员将重新表演一次某个场景——假装演员的表演不符合自己的要求。

big_bang_theory(from edge-online)

但是事实上演员只是想以此尝试不同的笑话。这种情景将多次出现,而观众笑得最大声的那次表演便会成为最终的喜剧片段。当电视播出时,观众会认为他们在观看一部精心制作的节目,但是事实上却并非如此。他们所观看到的都是录制当天观众反响最热烈的表演。正因为观众的反馈,最后播出的内容才能得到了最大的优化。

游戏?

不管是电影和电视娱乐产业都是出于相同理由去评估自己的内容:给自己最大的机遇而创造出最棒的体验。他们都承认并不敢保证自己的作品能否获得别人的喜欢,所以他们便让观众参与制作过程中而尽可能缩小犯错的风险。

所以其它产业也可以以此为经验,将目标用户整合到创造过程中帮助自己更好地评估产品。在游戏产业中,如果开发者准备好接纳测试用户,便能为自己的游戏迎来更多且更好的机遇。

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4,篇目5,篇目6(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

篇目1,Books and games

by Adam Rebika

It is pretty easy to guess why most people consider video games to be very close to movies as a medium: both use images to convey their stories. Yes, the “closeness” does not go farther than that.

Or, should I rather say, should not go farther than that. Indeed, I do believe that we should consider video games to be, as a storytelling medium (this analysis does not apply to the very large number of games that merely don’t need a story), treated as much closer to books than movies. To prove my point, I will analyze the main characteristics of each medium regarding specific points.

Length: How long does it take to go through the story?

Movies are ultimately a short medium. Most are 1h30 long, some can be 2, 3, rarely 4 hours long. Basically, in one afternoon or evening, you have watched the whole movie.

On the other hand, books take a lot longer. Now, it depends on how long the book is, and on how fast a reader you are, but we can all agree that most of the times, it takes around 1 to 2 weeks to read a book. Of course you can stumble upon a book that is so good that you’ll read in a couple of hours, but this is not really the norm.

It works exactly the same way for video games. I usually finish a game in 1 to 2 weeks, but can stumble upon a game which is so great that I’ll finish it in one day, even though it is pretty rare.

In movies, you don’t have a lot of time. You need to go fast, cut away everything you don’t absolutely need. The introduction rarely lasts for more than 20 minutes, and you can’t have that many twists and turns in the plot. That is why most movies only have pretty simple, straightforward stories, otherwise they may quickly lose their audience under the amount of information you want to transmit to him.

But when it comes to either books or movies, you have all the time in the world. Some books can have up to two, three thousand pages, while some games can last up to sixty or more hours. It is not uncommon for these mediums to have 5 to 10 main characters, all with their own developped personnalities and backstories – something movies can’t sustain.

Everything can happen a lot slower, and the introduction can last longer. Obviously, you don’t want a one hour long introductory cutscene, but you can afford to have 1, maybe 2 “prologue” levels before getting into the real action. Look, for example, at Fire Emblem: Path of Radiance: the actual plot does not start before the fourth mission, which is already, for most players, 1 or 2 hours into the game.

The length of this medium also have a strong impact on its rythm, something I’ll cover right now.

Rythm: What is the rythm of the story?

Since a movie is meant to be watched in a single stroke, with no interruption, most movies will follow the same rythm: strong introductory scene to get the spectator in (which is often loosely related to the main plot or will only make real sense halfway or more through the movie), then slow introduction to the characters and situation, exponential build up during most of the movie, climax and conclusion.

On the other hand, both books and movies are meant to be enjoyed over a long time, with long interruptions between every time you read / play. This is why you need a different rythm for the story.

You still have one big, main plot that slowly builds up until reaching the climax, but as it is stretched over a long time and meant to be enjoyed by small servings, you also need another, smaller and more complex organization for the story. Both books and video games are divided into chapters. Of course, the division is not always that obvious in games, but think about it: every game has either levels, dungeons, missions, quests… And each of these chapters actually contain a subplot, with a small climax and often a cliffhanger to make sure the reader / player wants to come back for the next chapter.

This forces you to cut your story in small, bite-sized chunks, but also allows you to develop one subplot for each of them, thus enriching your main plot. You can even dedicate one of these chapters to a particular character, allowing you to really develop every one of them much more than you could in a movie.

Communication: How is information relayed?

In movies, everything relies on what is shown and what is told. You can use a little bit of text (like the name of a place or some information shown on a panel) but rarely anything more. Of course some exceptions exist, such as the iconic Star Wars introduction, but they are what they are: exceptions.

Dialogs need to be short, as the watcher cannot follow a conversation that is too long. You can have very few monologs, and simpler is always better. The movie also relies a lot on the performance of the actors, and how good they are to relay emotions.

Books, on the other hand, rely on text. Everything is written down, every line of dialog and every description. When two characters are talking, it is up to the reader to picture their attitudes, emotions etc.

When it comes to video games, thanks to (or because of? this is a question I’ll raise in my next blog post) technology, voice acting has become a norm in most games. But a lot of data is still transmitter through text, and not always unimportant data (quests, lore details etc). But acting is still very limited in games, and only a handful of them have character models good enough to convey actual emotions.

Imagination: What room is left for fantasy?

Movies, of all mediums, are those who leave the less room for imagination. Everything is given to the spectator, every single detail of every single place / action.

On the other hand, books rarely describe everything. A lot is left to the interpretation of the reader, who usually likes personnalizing things a bit.

Same goes for games. A lot of games allow you to customize the main character, but things go even farther than that. It’s up to you to decide how things actually happen. The game or the book will only tell you: he fought and defeated 10 foes at the same time, and it’s up to the reader to imagine the battle and to the player to fight the battle.

Movies are also very limited by their race toward realism. You can’t have settings that look too fantastical, or the CGI will soon appear too obvious. You can’t have a main character that looks nothing like a human, or you’ll have trouble finding an actor for it. Of course you can still do an animated movie, but this means you’ll aim for a very specific public (children).

In books AND in games, you can imagine anything you want, and create it. In books, it’s up to the reader to imagine it, and in games, since everything is already virtual, you have no risk of having your settings look too unreal.

Sequels: What is the focus?

Movies are extremely limited when it comes to sequels. You often need to keep the same actors, and the plot has to be pretty close to that of the first movie. And you have your hands bound by the fact that actors do get older, so if you sequel is done 15 years after the first movie, you’d better find a story that takes place 15 years after the first one (of course you can still use make up to try and make him look younger or older, but only to a certain degree). And the spectators often create strong links between a movie and his main character, which means the actor playing this role.

Books and games have much less limits when it comes to making sequels, and don’t require to stick with the same character (and when they do, are not bound to make the sequels all happen in near chronological order). I think this is why both these medias make a heavy use of sequels (yeah, there are many books that are part of cycles or series). And you don’t have to stick with one single main character: as these stories do not rely that much on the actor’s face and performance, the reader / player’s focus can be shifted to any other element you want.

So, these where my two cents in a debate I hope will pick up, as it can actually help shape storytelling methods and tools in this still very new media.

篇目2,Opinion: Where do game ideas come from?

James Leach

Where do the ideas for games come from? Well, for a start they don’t usually get thrown into the ring as one-line pitches. You can do that with movies because movies – all movies – are more similar to each other than games are. A movie is just a story; a game is an experience.

Rarely can one person alone claim to have come up with a game idea – and people who have nothing more than an overarching concept are not going to get listened to. Not long ago, a fan collared Peter Molyneux at a show and told him that they had a great idea for a game. Molyneux replied that he himself had a great idea for a painting. It was a good answer in some respects – ideas are worth practically nothing. You can think up six astonishing game narrative concepts before breakfast.

No, the ideas behind the creation of new games are so often based in the mechanics. The place to start is a new and satisfying way of doing things. Look at LittleBigPlanet: there’s a game that’s not actually about anything. But it’s a fulfilling world in which any number of stories and experiences can be played out.

Creative writers in the industry often wail about how stories, plot and narrative structure are added to games later in their construction. But if games are thought up and created around cool things the player can do, that’s always going to be the case. It’d be nice if it wasn’t too late, though. And didn’t change. All the time. But these are games – telling the story doesn’t come first.

So if mechanics and gameplay are king, why do so many games seem to be like films? Once development has started, game design often borrows, and has always borrowed, from film and TV. How could it not, when every programmer and designer watches sci-fi, and every artist is in love with comic books and superheroes? There’s a long-distinguished tradition of developers immersing themselves in their favourite genres and rocking up at the crack of ten the next morning, determined to implement what they saw the night before.

And arguably there’s little wrong with this. It’s can be a useful shorthand. Would Max Payne’s bullet time have worked if we hadn’t seen The Matrix? Would StarCraft’s wisecracking marines and female pilots have been as cool without James Cameron’s Aliens? Would Gears Of War have worked as well? And grab a pen and list the games influenced by Giger. You may write on both sides of the paper. If the player understands the world from the outset, it makes it so much easier for them to get into the game. Everybody knows about explosions and shockwaves and fireballs from films, so we’re all on the same page.

Nowadays orcs, mech suits and warp jumps are public domain. They don’t need explaining. Like telescopic sights or lasers, we’re totally au fait with such things. You could call each a sci-fi convention if, er, that wasn’t something else. Such familiarity becomes a problem, though.

First, the game has to do the reference justice. Second, things date. Ironically, the more original an idea, the more likely it is to look passé at a later point. The aforementioned bullet time is a prime example. And third, there’s a fine line between borrowing cool concepts and simply copying. If Lara Croft had been a middle-aged bloke in a hat, things would have gone very differently for her creators.

It’s not just weapons and characters that draw on film. The universal rules of cinematography and plot do so as well – they have to. Cutscenes, for example, need to adhere to filmic principles. Similarly, plots and story also usually track the three-act structure and the Hero’s Journey. These rules exist because they work. Of course, some of the best movie-making bends or even breaks these rules and makes a virtue of doing so. This doesn’t happen in games, though, for two reasons: first, clever storytelling and plot manipulation won’t turn a poor or even a mediocre game into a masterpiece. Games are not about storytelling, remember. And second, games are far more linear experiences. Progression is everything, so you’re largely stuck with moving from one bit to the next.

As games look and feel more like movies, they increasingly ape – and run the risk of being stifled by – movie convention. You can only be influenced by things that already exist, so you’re always one step behind. When the new set-pieces start emerging in 3D film, as they surely will, you can bet they’ll be giving kids headaches on a 3DS near you soon afterwards. It could be called copying, it could be simply keeping sensibly to the convention. Hey, go the whole hog, imitate something enough and you can call it a homage. The up-to-the-minute LA Noire celebrates its ’40s and ’50s movie heritage with pride.

Sometimes we get the games the developers want to make. Sometimes the games may be the films they want to make. If it works, it works, though. And arguably it’s the icing on the cake. But I’m sure that if story, themes and gameplay fail to work together well enough, we keep our wallets closed. Psychonauts, anyone?

篇目3,Grand Theft Auto V’ Masterminds Explain How Game Design Differs From Filmmaking at the New York Film Festival

Eric Kohn

Budgeted at well over $100 million and grossing as much as $800 million in sales a day after it hit stores last week, Rockstar Games’ “Grand Theft Auto V” has been so insanely profitable in such a brief period of time that it puts all 2013 blockbusters to shame. Yet the commercial success of the latest open world crime saga from the New York game company has obscured the critical acclaim it has received at the same time. Building on the hype of 2008′s “Grand Theft Auto IV,” the latest game involves an ambitious story set in the fictional California town of Los Santos and allows the player to shift between three distinct characters: bank robbers Michael and Trevor and their new ally Franklin, a former repo man. When the trio is forced to engage in a series of antics by the FBI, “Grand Theft Auto V” provides ample explosive fodder for countless Michael Bay movies, but also presents a massive open world that allows players to wander beyond the main narrative and simply explore the city.

During last weekend’s NYFF Convergence, the multimedia conference taking place at the Film Society of Lincoln Center timed to this year’s New York Film Festival, several key members of the Rockstar development team took the stage for a conversation moderated by Revision3 Games producer and TV host Adam Sessler about the challenges of creating the “GTAV” world. The panel discussion started with a live play-through of one breathtaking sequence in which the player rescues a man held captive in a skyscraper; the action included piloting a helicopter and engaging in close quarters firefight, sniping at villains from across the way and taking down other choppers during the daring escape.

It was an ideal demonstration of the game’s breakneck speed, but also provided a peek at the sheer scale of the world as the chopper sped through the landscape. Appropriately, the panelists focused less on the narrative than environment surrounding it. Participants included Rockstar co-founder Dan Houser, Vice President of Publishing and Operations Jennifer Kolbe, art director Rob Nelson and co-writer Lazlow Jones, who also plays a memorable version of himself in the game. Here are some of the highlights from the discussion, which largely involved the contrast between game development and the filmmaking process.

There is no easy shortcut to designing these games. Rockstar has excelled at the creation of “the sandbox,” ginormous open worlds that allow players to roam freely in addition to play through the stories of their games. Los Santos, the city in “Grand Theft Auto V,” is the largest one yet, twice as big as Liberty City in the previous installment. And each street corner must be created from scratch. That’s why it takes years and years to produce these games, much longer than any traditional film production. “With a movie, you can go film in any set,” Kolbe said. “In a game, you have to build it.”

The biggest challenge for the game’s designers? Creating three main characters instead of just one. Houser said the prospects of switching between the characters without disrupting the real time flow of the game was a problem for developers up until a few months ago. “It was something we wanted to do first purely from a storytelling perspective,” he explained, “then it was only during the mission, but we really leapt on it when we got something from the non-narrative side of it.”

Because the games are so big, it’s not like you’re playing through a movie. A player who mainly engages with the story and doesn’t explore the world will still take up to 40 hours to complete all the missions in “Grand Theft Auto V.” That’s a huge distinction from the experience of a 90 minute movie. “We’re not taking narrative structure from films,” Houser said. Instead, he cited long-form television viewing and novels as precedents for their approach. That also creates a challenge: “We don’t know when you’re going to take a break. There’s a fear people will forget what’s going on.”

There are real performances in the game, and they’re quite good. The last “Grand Theft Auto” game also used motion capture technology, but the technique has grown incredibly advanced, to the point where art director Rob Nelson said that even an actor’s distinctive gait can be recognizable from the way they appear in the game. Facial expressions are similarly detailed, because the technology finds actors wearing helmets equipped with lights that illuminate their faces and capture each individual nuance. Nelson called the process “a mixture of theater and the ultimate closeup.”

The media satire is part of the game design. Anyone who has played a “Grand Theft Auto” game is familiar with the way the world parodies news coverage of violence and shows how the media informs its gritty setting. “It’s fun to parody America’s obsession with consumerism,” said co-writer Jones. But the satire actually exists outside the narrative: Designers have created thousands of fake advertising campaigns that appear in the game as well as audio tracks for various radio stations. The writers say they have heard from players who have pulled over in the game and listened to the radio; now, you can watch your character watch television at home. “What we’re trying to do is bring a world together that’s cohesive,” Houser said. “It’s about Americana more than America — as if the media came to life and walked the streets. That’s what we’re trying to investigate.”

篇目4,Spector: Games need to borrow from film less

By Leigh Alexander

Games often look to other media for lessons on structure and narrative, but imitation needs to be considered — we talk often about what we should take from other media, but not often about what we should not, argues Warren Spector.

“There are things that are sort of seductive and obvious that I think will hold us back as we become the medium we’re cpable of becoming,” Spector says. “Imitating other media seems to be a natural, maybe even necessary stage in every medium’s development. Building on a foundation provided by other media is pretty normal and natural.”

Movies themselves were born from attempts to emulate theater. Video games offer more of the “building blocks of storytelling” that any other medium has ever offered. “So how can we not tell stories? I often get confused when people say ‘games shouldn’t tell stories’ — I find that silly and amusing,” Spector says.

Yet games are more than “movies with interactivity,” of course. “If we’re nothing but an amalgam of conventions from other media, we’re in a world of trouble,” he says. There are yet more strides to be made in game storytelling even beyond games like Heavy Rain in which it’s a primary focus.

The similarities between games and movies — moving images on a screen, both with synchronous sound, creating a synchronous illusion of life — are so apparent they’re almost not worth mentioning, in his view.

“Culturally speaking, we share a lot with movies; movies were the medium of the 20th century that changed everything. It was the first time that everybody in the world could experience the same… cultural messages.”

“I think everyone can agree that games have overtaken those media,” Spector suggests. We ignore the “significant differences” between film and games at our peril, he continues. The editing techniques that dictate the experience of a film and how audiences are privy to information that the characters aren’t, for example, create a structure that doesn’t work in games.

“We need to jettison some of those,” Spector says. “It breaks the illusion; it wrests the experience away from players who want to be directors of their own experience. In most games the action is continuous… we either take control of the camera ourselves, or we leave control of the camera to the player.”

Players aren’t just watching, they’re actually engaged in real time with an experience, repeatedly. “In a weird way movies are not linear, and games are linear, in the way they treat time and space.”

The way games are paced is quite different from films, too. Clearly the runtime of a movie is only a fraction of the potentially-infinite time players can expect to play. Audiences are accustomed to the convention of film, but game developers sometimes have less than a minute to get players engaged.

“If you don’t get to your verbs quickly, and make them really action-y, or at least make them compelling in some way, your player’s going away,” he says. Approach to dialogue is also necessarily different, since dialogue is often designed to be reusable. A player may remain in the same area of the game for quite some time: “You have to find a hundred ways to say, ‘I thought I heard something,’” he notes, while a screenwriter can convey the necessary experience within a moment.

Game moments, too, must be designed to be reusable: The first time doves fly in front of a camera in a film, it looks cool — but if that happens every time a gun goes off, it becomes silly. It’s more valuable to let players make their own “magic moments,” rather than recuse that responsibility to visual editing.

Games are still beholden to their own tropes, too, burnened by Dungeons and Dragons conventions (“who wants to play a [video game] about rolling dice?”) The effusive Spector, who frequently joked at his own expense about the challenges of talking only for twenty minutes, stresses he doesn’t want to be “that guy who hates cinematic games.”

But he believes there’s more we can do without using established conventions from other media — like exploring plausible AI for applications other than combat, or by looking at the call and response in pen-and-paper games between the game master and the players– and by better understanding why techniques that work in film are often unique to it.

“There’s a point where we have to start looking at what makes us unique… we can transport players to worlds they can only imagine… We’re the only medium in history that responds to what players do. No one’s ever been able to do that,” he says. “…Except maybe LARPers, and they don’t count.”

“We’ve made progress, and we can get partway to where we’re capable of going by borrowing from other media… but we can only go so far. We need some original ideas,” Spector adds. “30 years after the creation of this medium, you have the opportunity to determine what it can become. It’s not too late.”

篇目5,The case for movie-length, narrative video games

by Eric Caoili

There’s a generation of gamers that many developers and publishers have forgotten — those players who first picked up their controllers 20 to 30 years ago, who no longer have the time or patience for today’s epic, protracted RPGs or even 10-hour blockbusters, but who would still be interested in interactive, story-driven experiences.

At least that’s the case argued by Ovosonico founder Massimo Guarini, who believes an entire generation of gamers has gone underserved by an industry that’s stuck “trying to appeal to a specific demographic, the immortal 15 to 20-years-old demographic.”

“[The gamers who were playing] Mario 20 years ago or Donkey Kong 30 years ago, they don’t have the same amount of time anymore,” he tells Gamasutra. “They have kids. They have jobs. They come home in the evening, they’re tired, and they have to manage their lives in a totally different way than a 15 to 20-year-old kid.

“When you are in that situation, and when you sit down on the couch after dinner with your family, if you’re given the choice between a movie and you know that’s going to be over in two hours and that’s it, or a game and you never know when the game is going to be finished and how much effort is going to be required from you, it’s obvious. We’re basically lazy, right, so you’re going to choose the movie.”

Social and mobile game developers offer an alternative with games that can be played for just minutes at a time, but Guarini says there are few options for those who want something in between those disparate experiences, who want a satisfying story-driven game they can consume in an afternoon.

That’s why, after leaving Grasshopper Manufacture where he directed cult shooter Shadows of the Damned, he wants to now create a movie-length game at his new studio in Milan. His hope is to make something for that forgotten generation, for players with little free time and a preference for games about more than “trivial subjects like space marines.”

This void of short narrative-focused titles is one we’ve seen filled by more and more independent developers lately, like Thatgamecompany’s powerful Journey and Plastic’s psychedelic PSN experiment Datura, but are gamers really clamoring for these condensed releases?

Portion control with digestible games

Though more short-format titles have released recently, there’s still a stigma among many consumers that games need to hit a quota of hours to earn their money. And when a release fails to reach that arbitrary length requirement for an RPG or a narrative-based game, it’s not common to see consumers and even the enthusiast press bemoan that perceived weakness.

“It still amazes me that some gamers are happy to explicitly say they don’t care about the quality of a game, it’s only the dollar-per-hour cost that defines value for them,” says Dan Pinchbeck, who was the creative director on Thechineseroom’s critically acclaimed two-hour-long PC title Dear Esther.

“I find that completely extraordinary. It’s like going for a meal and basing whether it’s any good on how much food you get served rather than whether it tastes nice. I don’t see shoveling crap into myself as good value on the basis that there’s a lot of it.”

Trailer for Dear Esther

Pinchbeck isn’t alone in the quantity versus quality debate when it comes to game length — Gary Whitta, movie screenwriter (The Book of Eli) and story consultant on Telltale’s excellent episodic game The Walking Dead, complains that most of the content in mega-sized games is filler.

He also champions the idea of creating short “digestible” experiences that won’t scare away gamers with limited leisure time. “If you put a kind of massive, massive man versus food plate in front of me, that to me like is Skyrim,” says Whitta, continuing the food analogy. “I’m like, ‘Oh my god. How am I going to get all the way through this?’ What I’m looking for is just a nice plate of food. Just the right portion.”

“That’s a nice way to look at it, kind of portion control in gaming — just finding that right amount of food on your plate where you feel like you’ve had just enough, where you feel full, you feel satisfied. You don’t have that experience where you’re like, ‘Oh my god. Just because I needed to clear that plate, I ended up feeling kind of sick with how much I ate.’”

Changing expectations and price points

While it’s unclear yet if a class of gamers waiting for short format titles actually exists, the growing popularity and acceptance by consumers of digital distribution across consoles, PCs, and smartphones could help developers overcome this stigma short games have suffered over the years.

Because downloadable titles tend to be smaller games — due to tighter budgets, a platform’s file size limitation for downloads versus discs, or various other factors — many users have different expectations for those releases, and can be more receptive to compact experiences.

Ovosonico’s Massimo GuariniGuarini thinks the pricing for games on these download platforms is also going a long way in acclimating users to shorter but cheaper games. He comments, “You can actually lower the price since you don’t have the cost of goods, which is basically what brings the price up when you go retail. If you sell a two-hour game for $60, it’s not going to work obviously.”

“You need to be competitive with similar forms of entertainment,” the Ovosonico head adds. “Like movies on Blu-ray, it’s like, what, $15, $20? So, that’s about the price range that it’s worth, I think, for a two-hour game format.” (That’s a bit more expensive than Dear Esther, which sells for $10, or the $5 episodes of Walking Dead, though it’s in line with Journey’s pricing.)

Asking consumers to pay that much for a short game, though, can put more pressure on developers to deliver a game that’s engaging all the way through. “I think maybe for some people it feels like more of a risk to pay less for a shorter game,” notes Pinchbeck. “If you pay $60 for a 40-hour game, it’s likely that at least some of those 40 hours will be good. If you are paying $10 for three hours, all three hours have got to be brilliant.”

At the same time, there’s a danger in discounting games too much just because they’re shorter, devaluing them to the point where consumers believe that their time in a game is only worth $1 an hour — you might end up with games that only put in $1 per hour’s worth of effort.

“Games like Dear Esther require a heavy investment in assets to get the production quality up,” says Pinchbeck. “If we were limited to an App Store price-point for the game, there’s no way we’d have invested in next-gen visuals. It’s the normal contract – we want you to invest in our innovation, and we have to supply an experience that supports that investment. If you only want to invest peanuts, you can’t complain if developers design to that budget.”

Big publishers lacking confidence

If there’s a potential audience for short story-driven games, and if there’s a system in place that makes it possible for those kind of titles to reach consumers, why aren’t more major publishers trying out this format? Where are the movie-style game releases from companies like Electronic Arts and Activision that offer an interactive alternative to blockbuster summer films?

Guarini believes many game makers are just too scared to try anything new, to make games that are more condensed than the titles they typically create, and offer a cinematic experience with a narrative that’s more than just shooting bad guys within that framework.

“We actually don’t have much confidence in what we do,” he says. “Especially publishers, they don’t have much confidence in being able to come up with different subjects in video games. We’re a relatively young industry at this point. We’re nothing like movies at this point in terms of business and in terms of like, I would say, level of maturity in that sense.

“So, there’s a sense of resignation that we’re all constrained with [thinking] basically, ‘Okay, that’s what has worked up to this point. That’s what we’re going to do because that’s what sells.”

Pinchbeck points out that it’s also expensive for bigger companies to develop new and unproven IPs, and there’s the prohibitive cost of tools to consider, too. “If you are going to invest a lot in that, you need to justify that development with a price-point, and to achieve that, you need to increase the scale of the game to justify that price-point.”

Short-format games are all about pacing

For those developers that decide to create story-driven, movie-length games, there are a number of changes with this different approach they must take into consideration, the obvious being that the production cycle and development time will be much shorter compared to working on traditional projects.

There’s also a greater emphasis on pacing and density when designing these titles — players must feel like every minute they spend with these games offers something fun or interesting or engaging for them to experience. Again, there’s little room for filler when players are spending more per hour on a short-format game than they would on a $60 40-hour title.

Screenwriter Whitta says that the film industry learned a long time ago to not worry about length and just focus on the pacing of the experience. Though people seem to have opposite expectations with the two mediums, where they tend to be put off by three-hour films but look for games that can take them weeks to finish, pacing and density make all the difference when it comes to whether they enjoy movies regardless of their length.

Telltale’s The Walking Dead

Game makers that manage to master pacing in a film-style title, keeping players absorbed all the way to the end, can also enjoy a reward most directors behind today’s triple-A releases don’t get: the satisfaction of knowing their audience is more likely to experience their entire production as it was intended (without interruptions) and appreciate what they tried to accomplish with their story.

Freedom to experiment

With their smaller budgets and shortened production cycles, narrative-focused, movie-length games can offer developers more opportunities to experiment with their titles. It’s not only a chance to introduce an original IP, they can try new ways of telling interactive stories, and find excuses to produce content completely different from the usual stuff they’ve likely grown used to making for many, many years.

For Guarini, who’s waiting until later this year to reveal what Ovosonico’s first cinematic game will be, short-format games also allows his studio to try out an unconventional way of structuring his team — along with making film-style games, he’s trying out the movie studio approach of having a small creative team, and hiring around that group for specific projects instead of keeping a complete crew around permanently.

“I think the secret will be having this creative core that is basically the director, the producer, [etcetera] in-house,” he explains. “That’s particularly for these kind of short games that are a little bit more targeted to specific audiences. That means that you can be a little more personal in what you say in the game, a little more niche if you want of course.”

Guarini says it’s still too early to tell how this experiment will play out, but like story-driven, short-format games, it’s a model he predicts we’ll see a lot more of in the future from indie teams.

篇目6,What games can learn from Hollywood and TV

Graham McAllister

We’ve all played a game at one point and asked ourselves, “What were the developers thinking? What’s meant to be enjoyable about this?” Often, a game just isn’t for you, but sometimes, it simply isn’t for anyone, and ideas which sounded fine to the developer during production just don’t resonate with the game’s target audience.

One of most common causes of this is that many developers simply have no idea who is going to be playing their game. In fact, it’s common for games to be made based on what studios think players will enjoy – based, more often than not, on the developers’ own tastes.

Perhaps this stems from the origins of our industry, with games being developed in bedrooms by one person, making a game because they themselves want to play it. Even with the larger teams that we have today, it’s often the case that key decisions are being made by only a select few in the studio. Is their opinion really any more valid than anyone else’s?

And opinion is all it is, most of the time. Sure, we all have experience, but when it comes to designing successful games, what’s really needed is not opinion, but evidence that the design is sound. It’s all very well coming up with a game concept, but if you want to increase the likelihood of success then evaluating designs before release would seem like an intelligent approach. This evaluation of creative content is precisely what happens in the other entertainment industries, yet somehow, videogames have been slow to embrace these methods.

Movies

The movie industry has been evaluating what audiences think about upcoming releases using test screenings since 1928. A representative audience is recruited, and screenings of the full movie and alternate endings are shown. After the credits have rolled, questionnaires may be filled out, audience members may be selected for interview or the director may review video recordings of the audience to watch their reactions at key moments.

Does this process improve the movie experience? Undoubtedly. Many movies have been improved by changing actors, tweaking narrative, creating space for the audience to react, building tension, or balancing engagement levels. Movies such as Jaws, Shaun of the Dead, and 28 Days Later were all improved by test screenings. During screen tests of Johnny English, problems were identified with the introduction of the main character. The beginning of the film was re-shot with a focus on addressing this issue and the resulting test scores increased considerably.

It’s also often the case that once a director has made an edit based on results of a test screening, they are often surprised at how badly they made the original edit in the first place. Even experienced directors admit that their creative output needs validation: Woody Allen says that it’s easy for him to write a script, but he’s no idea if it’s any good until he sees an audience’s reaction. This inability to see our own mistakes is something I’ve mentioned before, and it’s as true for videogame development as it is for the movie industry.

TV

The TV industry takes the creative evaluation process one step further and performs realtime testing of comedy material during live recording. During a recent tour of the Warner Bros studios, I was told how they record Big Bang Theory to ensure the best possible outcome. After a particular take, the director may say to the audience that the cast are going to try that scene one more time, pretending that he didn’t get the shot he wanted.

What’s really happening, however, is that the actors are going to try out a different joke. This could happen multiple times and the joke with the biggest laugh will be the one which makes the final cut. When aired, the viewer thinks they’re watching one carefully crafted show, they’re not. What they’re experiencing is the best possible permutation of jokes as rated by the test audience on that day of recording. The episode that ultimately airs has been optimised thanks to audience feedback.

Games?

Both the movie and TV entertainment industries evaluate their content for the same reason: to give themselves the best possible chance of creating a great experience. They openly admit that they’re not sure if their creations will be enjoyed by others, so they put processes in place to minimise the massive risks of getting it wrong.

What these other industries have learned from experience is that involving their target audience in evaluation produces better results than if they ignore them. For our industry, then, opportunities for both better and more original games exist if studios are prepared to embrace them. But are their arms – and minds – open?

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号