长文整合:解构设计中的数学、艺术和游戏性

作者:Brian Powers

随着多种媒体生产形式的发展,小预算发行游戏对个人来说越来越容易。近年来,我们看到越来越多业余游戏设计师如雨后春笋般迅速成长起来。2008年,卡牌游戏的小成本经营从根本上说是没有出路的,但现在,像Superior POD和 the Game Crafter这类网站不仅使个人发行游戏成为可能,还简化了这个过程。然而,这并不意味着你可以靠游戏一夜暴富或一朝成名!哈哈!我们做游戏不是为了钱!我们是艺术家,我们为的是信仰!

但我们还是不要操之过急了,至少在我们发行游戏之前,我们得先设计,在设计之前,我们必须先明白一些概念。理念可以产生于任何地方——最无趣的地方也可能是灵感之源,但正如Ze Frank(游戏邦注:美国在线幽默表演艺术家)精僻地指出:我们应该先做点什么而不是等待灵感的出现。灵感无处不在。

我有许多游戏想法:有些我已经实现了,有些还搁置着。

Pensacola:在这款策略游戏中,玩家要好好经营养老院,防止养老院里的住户离开。

Crazy Celebrities:玩家在这款卡牌游戏中扮演超级名人(游戏邦注:如Tom Cruise、 Lindsay Lohan或Charlie Sheen等),要小心不要毁掉自己的星途。

Get Sick:玩家在这款卡牌游戏中装病欺骗老板,让自己请到病假。

Cult Classic:玩家在这款卡牌游戏中比赛找信徒,引诱到最多的追随者的玩家获胜。

Pathways:这是一款抽象的拼图游戏,玩家要在A和B两点之间联结路径。

Element Tower Defense:这是我几年以前做的一款新奇的塔防游戏,可以在《魔兽争霸3》中玩。

我的想法还不止这些。

在此我想谈的是在我脑中酝酿了一阵子的一个游戏理念。我还不知道怎么命名,但愿写完本文后我能完善它。在这款游戏中,玩家控制他们从各种行动中得到的奖励,然后有策略地采取这些行动。这是我能想到的最简单的描述了,但为了更深入的讨论,我想先谈谈什么是游戏理论。

博弈论是一个数学运算的集合,广泛运用于经济学、政治学、国际关系、社会学、生物学……总之,就是为了最大化或最小化某些对个体或集体本身有积极影响的结果,该个体或集体必须制定战略决策。这些情形对“游戏”来说比较抽象,且是用矩阵这类数学工具分析的,我们通常可以找到游戏的“解决方案”或理想的策略集合。“博弈论”这一用词并不恰当,因为该理论实际上并没有太专注于我们玩的游戏,但这么命名就是这么回事。

上面这些看起来太死板了,我们来列举一个经典的例子(其实是我最近才萌发的游戏概念):

假设有两个人,各有两个选择:友好或卑鄙。如果两人均选择做个友好的人,那么他们各奖励3分。如果他们都选择当恶人,那么各得1分。如果一个友好一个卑鄙,则友好者得0分,卑鄙者得5分(无论他们从事什么,卑鄙者都占优势)。我们可以将这种情形用矩阵描述出来。玩家1和玩家2的得分情况如下:

这个情形就是所谓的“囚徒困境”。之所以是困境,是因为尽管你知道双方都能得到的最大利益产生于彼此都友好时,但双方都有强烈的变卑鄙动机。但是,如果双方都卑鄙,他们只能各得到1分,而双方都友好时各得3分。

关于囚徒困境的研究和文章已经非常多了。尽管我觉得很有趣,强烈推荐读者阅读Robert Axelrod写的《The Evolution of Cooperation》——不过在此我就不赘述这本书中的内容了。我感兴趣的是如何将这个形情变成一款桌面游戏。

如果能通过重复游戏变动奖励,这款游戏会更有趣得多。当你识破对手的策略时,你大概可以重新平衡奖励,或选择可以让自己占上风的行动。

我所面临的挑战是:

*使游戏适合2名或以上的玩家

*使游戏具有策略上的趣味

*使游戏具有美学上的享受

*使游戏不依赖无关紧要的游戏部件。

说这些是“挑战”可能太夸张了——只是需要执行但我还没执行的步骤罢了。我觉得这个游戏创意不错,希望行得通。

就这样,我们有了一个理念。下一步是想出游戏的机制!什么是游戏机制?

1. 由多少玩家能够进行游戏体验?

2. 游戏的目标是什么?

就玩家数量而言,我想你可以将游戏分成如下类型:

* 个人主义的竞争游戏——每位玩家都想要胜出,但赢家只有1位。

* 联合竞争游戏——来自2个或过个团队的玩家相互竞争,只有1个团队会胜出。

* 完全合作型游戏——玩家共同克服游戏设计固有的障碍。

我喜欢完全合作型游戏,虽然我并没有玩过很多有趣的合作型游戏。虽然我有引入若干联合建造元素,但我的游戏属于竞争类型。

关于游戏目标,最常见的模式是成为得分最高的玩家。得分可以基于现金、财产或是抽象积分。有些游戏采用这样的设计方式:玩家逐步被淘汰,最终存活的玩家就是赢家。这些游戏存在内在弊端,当玩家离开游戏后,游戏对他们来说就不再有趣。另一获胜条件也许是个球门柱——成为首个到达目的地的玩家。

不同人对于优秀作品有不同定义。在有些人看来,《大富翁》就是款很棒的游戏。但我认为如下元素构成优秀游戏作品:

* 自动平衡:如果有人处于领先位置,游戏应向其呈现更复杂的内容。同样,我们向输家通过获胜机会。

* 选择:游戏应向玩家呈现有趣且富有挑战性的决策。

* 给所有玩家带来乐趣:在赢家和输家眼中,游戏都应富有趣味。

* 重玩价值:掌握策略应花费较长时间,所以游戏反复体验起来应该富有趣味。

你多半会同意,《大富翁》缺乏这些特性。富人更富,而穷人则逐渐衰弱,进而消亡。游戏只对富人来说富有趣味,而输家则逐一被淘汰。从本质来说,游戏主要围绕掷骰子,以及在能力范围内购买尽可能多的资产,丝毫不涉及决策元素(游戏邦注:除选择要购买小狗还是帽子外)。

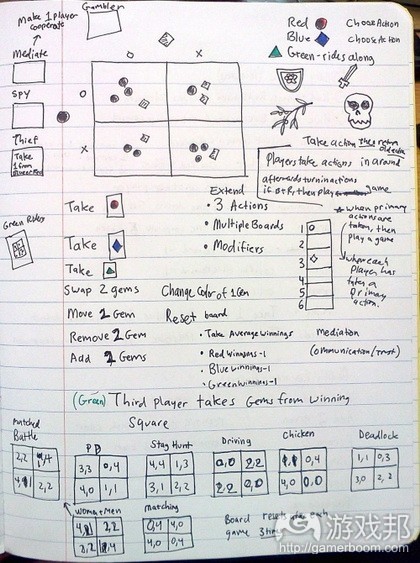

在深入谈论话题前,我想要呈现都对于新作品的构思草图。这只是要告诉你,虽然我在文中的观点相当有条理及颇为连贯,但构思游戏设计无需如此。

从根本来说,我的游戏由两个要素构成:

1. 玩家轮流做出战略决策,以获得分数奖励

2. 玩家修改源自战略决策的奖励

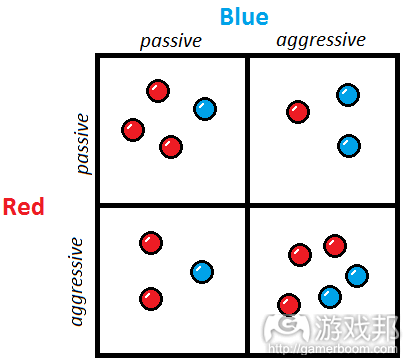

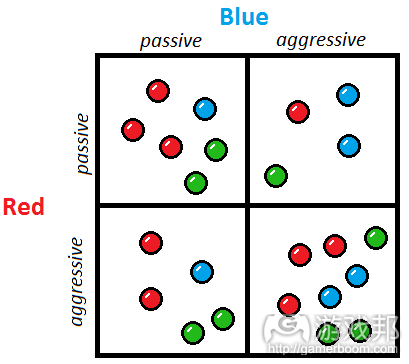

我正在构思一个看起来像是网格的简单游戏面板,其中包含红和蓝玩家的奖励,这些奖励由网格中的小标记表示。这些彩色装饰道具可以在游戏过程中进行添加、移动或移除,进而修改奖励。

红和蓝玩家会同时但秘密选择某个操作,出于简单起见,我们将操作称作“消极”和“进取”类型。各动作组合的奖励就会对应呈现。在上述情境中,假设蓝和红玩家选择“进取”操作;红会收到3个积分,而蓝则只会收到2个积分。

将游戏玩家增至2人以上,我想象第3位玩家会扮演什么角色。如果第3位玩家无法控制自己的命运,相反只是基于红和蓝玩家的操作获得奖励,会出现什么情况。我们不妨将第3位玩家称作“绿色”玩家,以小型绿色装饰道具代表他的奖励:

在红和蓝玩家采取行动后,绿色玩家将获得已知回馈——也许这会影响红和蓝玩家的决策。事情开始变得有趣!

显然玩家应该要能够替换红、蓝和绿角色,我们要允许融入更多玩家,而非仅仅是3位玩家。我们能够做到这点。但我们还需要思考如何修改游戏奖励面板。

修改游戏面板可以通过2种基本方式完成:做出细微变更,或重新设置面板。细微变更包括移动1个装饰道具,就其中两个道具进行替换,改变某个道具的颜色,添加或移除其中一个等。关于重新设置,我想到的是将若干原型情境运用至游戏中。我觉得这些非常有趣,所以我会向你呈现奖励矩阵,同时提供简要说明。此外,为将游戏的评分机制标准化,我决定将原型给予各位玩家的奖励设置为0-4之间。因此每个回合的积分奖励能够保持一致。网格各象限的数字是有序对:头1个是红色玩家的奖励,第二个是蓝色玩家的奖励。

囚徒困境

联合采取消极举措能够带来较多回馈,但各玩家难抵进攻的诱惑。而且联合消极举措会将双方玩家置于不利地位。真是进退两难!

猎鹿博弈

双方玩家将通过采用消极举措获得丰厚回馈。玩家只有在怀疑对手会采取进攻手段的情况下才会忍不住发动进攻。这和囚徒困境类似,但略有不同,因为进攻诱惑没那么强烈。

尴尬的人行道

可以将游戏想象成两个行人在人行道上相向走来。若双方都坚持到底,那么他们就得尴尬地停下脚步。如果他们双方都走向侧边,那么尴尬情况又再次出现。双方只有在某位玩家继续行走,而另一玩家走到侧边的情况下方能获得奖励。

谁是胆小者

两个人驱车前往悬崖。最后刹车的人胜出。我们可以将操作想象成“提早刹车”和“等待另一人刹车”。胆小者提早刹车,得不到任何回馈,而勇敢者将获得丰厚奖励。但如果两位玩家都等候另一人先刹车,那么他们就会掉落悬崖,彼此都无法获得奖励。

我还构思出其他原型情境,各情境都包含不同心理学特征及策略。我将游戏的整体结构构想成:

面板由基本原型情境入手,玩家修改奖励;红和蓝玩家选择操作,然后获得积分。在面板重置成新的游戏模型前,这一过程持续重复。将绿色道具投掷至面板中,我们因此能够随机将它们放置于面板上。这可以通过提供绿色道具陈列的纸牌完成,或者可以通过掷骰子随机完成。这不太重要,无需现在做出决定。

我想要采用的游戏机制是有限操作(Limited Actions)和刺激不受欢迎的操作(Unpopular-Action Sweeteners)。

有限操作

这不是原始构思;这之前曾出现在《Agricola》、《Puerto Rico》、《Citadels》和《Meuterer》之类的杰作中。从根本来说,玩家被赋予有限操作(游戏邦注:没有两位玩家能够在一个游戏回合中采取相同的操作)。

刺激不受欢迎的操作

我玩过的有些游戏就是采用这一机制。如果没有玩家在游戏回合中采取某一操作,那么操作就会因附带奖励而变得颇有诱惑,促使下个玩家采取这一举措。每次当依然没有玩家采取这一举措时,另一奖励就会附着其中。这样所有操作都会在不同时间都富有吸引力,玩家就需要判断什么时候非战略举措变得颇具吸引力,值得他们执行。

在我看来,采用先前的游戏机制没有什么不妥。要制作出各方面都保持创新的作品很有难度。但我认为在游戏中进行创新非常重要:也许是植入可靠的机制,或者也许是创造新鲜内容。修改奖励机制我之前没有见过,所以我对此非常感兴趣。

1.理念:明确游戏是关于什么。

2.游戏设计:玩家将如何玩游戏?游戏规则是什么(游戏组件,游戏目标等)?

3.最初原型:制作一个虽然简单但却具有可玩性的游戏原型。

4.游戏测试:测试游戏并判断哪部分可行哪部分无效,并相应地做出调整(不断重复这一步直到不再需要做出任何改变)。

5.发行:自己发行或与其它发行商合作。

虽然为游戏画图或添加色彩(这针对美学角度而言)非常具有吸引力,但是我们却希望能够量力而行。现在我们需要做的便是创造一个具有可玩性的基本游戏原型。我们希望在花时间为游戏画图并添加色彩之前先明确它是否具有可行性。游戏原型不需要太过华丽;而这时候我们需要进行第一次游戏测试以确认游戏设计是否有趣,是否存在哪些需要改善的内容,以及是否有那些地方描述过于含糊而需要进行修改。除此之外我们还必须面对现实:游戏到底有没有效?

我们可能会遇到一些无用的游戏!并非所有游戏理念都是合理的,所以不要对此感到纠结。而你必须亲自实践才能做出判断。你只有进行反复的测试才能尽早明确结果,并在遇到真正优秀的游戏理念时把握它。

所以让我们开始建造游戏原型!我的游戏非常简单并且也不依赖于任何奇幻的游戏部件,但是如果你想要创造一款带有额外修饰的游戏,那也可以创造一个游戏原型,并且不需要你投入过多的时间和成本。以下是一名游戏开发者在测试时的必需品:

空白卡片

如果你想要确保内容的简单性那就可以使用索引卡。而如果你希望卡片的使用寿命能够长一点且更容易操作与洗牌的话,你便可以购买空白卡片。你可以在亚马逊购买售价7.2美元的空白卡片(一盒500张)。

我认为这对于游戏设计师来说是不可或缺的必需品。索引卡片也行,但是如果你真的想要进行游戏测试,你更需要那些容易操作的卡片。你可以在这些卡片上使用铅笔记下或做出一些永久性的标记,从而帮助你顺利完成工作!

游戏图板

你可以从当地的工艺品店购得一些硬木板,并将其裁剪成合适的大小。如果你不在乎木板的厚度的话就没关系,但是一般制作卡片的纸料或纸张的厚度就可以了。

骰子

你可以使用6面骰子,或者你也可以创造出一款使用4面,8面,10面,12面或20面骰子的游戏。你可以在游戏商店或网上买到便宜的骰子。就像在我们当地的1元店一盒骰子(10个,5个白色5个彩色)就只卖1美元。

计数器,代币,钱,兵卒

在创建游戏原型时你可以使用各种道具作为游戏部件,而如果你想要创造许多原型你最好拥有一个小小的游戏部件库。你可以在The Game Crafter等商店中购买到它们,并且游戏部件的价格也不会太高!就像如果我需要彩色的代币,我便会到Michael’s Arts and Crafts购买几袋彩虹玻璃宝石(它们正在做促销,即每袋只需要1美元!)

另外一个选择便是购买一大箱的彩色方块。1厘米的彩色方块是教师们的教学材料,但同时它们也是非常棒的游戏计数器,代币等道具。塑料方块也是如此,它们既能作为教师的教学道具同时也可以是游戏中用于记分的计数器或代币。我们可以很容易在网上找到透明或非透明的方块。

创造游戏原型并不会花费我太长的时间。比起长篇大论地解释我是如何建造原型我更希望以照片呈现出来:

我希望尽可能确保原型的简单。我有2套行动卡片,上面那一套是修改行动,即让玩家能够修改游戏图板中的奖励。而第二套则是奖励行动,主要呈现玩家是如何获得分数。

除此之外还有策略行动卡片,一套是蓝色的X还有一套是红色的O。这些卡片让分别代表红色和蓝色的玩家能够秘密选择行动,并同时展示出来。最后还有两套分别面向红色/蓝色和绿色的游戏图板设置,以及“领导者”卡片——将向每个玩家分发表格从而让不同玩家都拥有优先选择行动的机会。

我只需要使用几根Sharpie钢笔便能将这些游戏部件组合在一起。我并不需要使用任何牌背。你会发现整个过程如此简单。然而我只要完成这些就能邀请好友们帮我测试游戏。

相关拓展阅读:篇目1,篇目2,篇目3(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

Math, Art and Game Design

by Brian Powers

Part 1: The Game Concept

When Chlo? asked if I’d be interested in writing a guest post on Real Life Artist about game design, I FIGURATIVELY jumped at the chance! Although I’m a mathematician by training, a banker by experience, and a teacher by occupation, I consider myself an amateur game designer.

As with many forms of media production, game publishing has become more and more feasible for the individual with a small budget in recent years and we’ve seen a burgeoning burgeon of amateur game designers coming onto the scene. In 2008 there were essentially no options for an affordable small run of a card game (one or two copies), but now websites like Superior POD and the Game Crafter make it not only possible but relatively simple to publish your own game. This does NOT, however, mean you will make money from the game or become famous! Haha! We don’t do this for money! We are artists! We do it for Zeus!

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves—before we publish a game, we have to design it, and before we design it, we need some sort of concept. The concept can come from anywhere—the most boring place is a flash of inspiration, but as Ze Frank nicely explains, we shouldn’t wait for inspiration before we make something. We can look for ideas everywhere.

I’ve had many ideas for games: some I’ve acted upon, and some are on the back burner.

Pensacola: A strategy game where players run competing retirement homes and try to make money before their residents “move on”.

Crazy Celebrities: A card game where players are celebrities trying to become crazy (like Tom Cruise, Lindsay Lohan or Charlie Sheen) without destroying their careers.

Get Sick: A card game where you try to fake diseases to fool your boss into letting you take sick days.

Cult Classic: A card game where players compete to found cults and lure the most followers they can.

Pathways: An abstract tile-placing game where you build a connected path between points A and B.

Element Tower Defense: A novel tower defense computer game I made a number of years ago, to be played in Warcraft III.

And the list goes on.

The game that I want to discuss here is a concept that I’ve been playing with in my head for a while now. I’m not really sure what to call it but we’ll hopefully see it evolve as this series of blog posts develops. The game involves players manipulating the rewards they receive from various actions and then strategically taking these actions.

That’s the simplest way I can describe it, but I want to talk a little bit about Game Theory in order to delve further into it.

Game theory is a branch of mathematics with heavy applications to economics, political science, international relations, sociology, biology … any situation that involves one or more individuals or collectives making strategic decisions in order to maximize some sort of positive result for themselves. These situations are abstracted into a ‘game‘ and represented using mathematical tools such as matrices for analysis, and often we can find the ‘solution’ or ideal set of strategies for the game. The name “game theory” is a bit of a misnomer because the theory really isn’t so much focused on the games we play for fun, but that’s the name it’s stuck with.

This may all seem pretty dense, so let me present a classic example (in fact, the inspiration for this latest of my game concepts):

Consider two individuals. Each person has two options: be nice or be mean. If they are both nice then they are rewarded with 3 points each. If they are both mean then they are given 1 point each. If one is nice and the other is mean, then the meany gets 5 and the goody-two-shoes gets nothing (out of whatever deal they make – the meanie takes advantage). We can depict this situation as a matrix, with each box showing the points for player 1 and player 2 as an ordered pair:

Player 2

Nice Mean

Player 1 Nice (3, 3) (0, 5)

Mean (5, 0) (1, 1)

This situation has come to be known as the prisoner’s dilemma. It is a dilemma because although you can see that collectively the greatest benefit for the pair is when both are nice to each other, both players have a tasty incentive for meanness. If both players are mean, however, they are stuck with each getting a low reward, a third as much as they would have got if they had been nice in the first place.

The prisoner’s dilemma has been studied and written about A LOT. Although I think it’s completely fascinating—and I can’t recommend enough the book The Evolution of Cooperation by Robert Axelrod—I don’t want to dwell on it. What I’m interested in is how this could be turned into a board game.

The game becomes a lot more interesting if the rewards could be adjusted through repeated plays of the game. As you begin to recognize your opponent’s strategies, perhaps you can re-balance the rewards to favor yourself, or choose actions that will give you the upper hand.

The challenges I’m facing are:

make the game fun for 2 or more players,

make the game interesting strategically,

make the game aesthetically pleasing (in other words: fly!),

design it in such a way that it doesn’t rely on extraneous game pieces.

Calling these “challenges” may be too dramatic – they are just steps that need to be taken, and that I haven’t taken yet. I feel good about this game idea, and I’m eager to see it through. Hopefully the process will be interesting enough for you to want to read about.

So we have a concept. The next step is to figure out the game mechanics! What are game mechanics? Obviously they are little grease monkeys who play checkers all day. (If you have an infinite number of grease monkeys with an infinite number of checkers boards, would they design Monopoly? Maybe they need an infinite number of typewriters too.)

In our next installment we’ll get all into game mechanics and some of the nuts and bolts of game play design!

At its core, a game is a an interaction comprising a certain number of players who are trying to reach some sort of goal, so two fundamental questions to answer about your game design are:

1. How many players can play?

2. What is the goal of the game?

As far as the number of players goes, I suppose you can classify games as:

* Individualistic competitive games – each player is trying to win, and there is only one winner.

* Coalition competitive games – players form 2 or more teams which they compete, one team being the winner

* Fully cooperative games – the players all work together to overcome some obstacle inherent in the design of the game.

I love the idea of fully cooperative games, although I haven’t played many fun cooperative games. And though I may include some aspects of coalition-building, my game is going to be strictly competitive.

With regards to the game’s goal, I’d say the most common goal is to simply get the highest score of all players. Score could be based on cash, property, or just simply abstract points. Other games are designed such that players are eliminated as the game goes on with the winner being the last remaining player. These games have an inherent drawback in that the game ceases to be fun for a player once he is out of the game. Another winning condition could be a goalpost – a race to be the first to reach some milestone (this could be a certain number of points, for example).

Different people have different qualities they look for in a good game. For some people, Monopoly is a wonderful game. However, I’d posit that these are the qualities of a good game:

* Self-Balancing: If someone is in the lead the game should be harder for him. Likewise, we want opportunities for underdogs to triumph.

* Choices: The game should present players with interesting and challenging decisions to make.

* Fun for All: The game should be as fun for the winner(s) as it is for the loser(s).

* Replay Value: Mastering the strategy should take a long time (if possible at all), so the game is fun to play over and over again.

Hopefully you agree that Monopoly has NONE of these qualities. The rich get richer in while the poor wither and die. The game is only fun for the rich, while the losers are eliminated one by one. The game is, in essence, rolling dice and buying as much property as you can afford with almost no decision-making – besides choosing whether to be the doggie or the hat. (Obviously you want to be the battleship! It has guns, duh! And if you go broke you can sell it for millions of dollars!)

Before going any further, I want to show you a page from my brainstorming for my new game. This is just to show you that although my thoughts in this article are relatively organized and coherent, brainstorming the design of a game does not have to be!

Essentially my game consists of two aspects:

1. Players take turns making strategic choices to receive scored rewards, and

2. Players modify rewards that result from strategic choices.

I’m imagining a simple game board that looks like a grid, with Red’s and Blue’s rewards represented by little markers within the grid. These colored baubles can be added, moved or removed during the game to modify rewards.

Red and Blue simultaneously but secretly choose an action each, of two that I will call “passive” and “aggressive” for simplicity’s sake. The reward for each combination of actions is then doled out accordingly. In the above scenario, let’s say both Blue and Red choose the “aggressive” action; Red will receive 3 points and Blue 2.

To extend this type of game to more than two players, I imagined what role a third player might take. What if the third player did not have control of his own fate, but instead just received a reward based on the actions of players Red and Blue. Let’s call the third player “Green” and show his rewards with little green baubles:

After Red and Blue take actions, green is rewarded with known rewards – perhaps this will influence the decisions of Red and Blue. Things are starting to get interesting!

Clearly the players should have some sort of way of alternating who gets to be Red, Blue and Green… and we should extend this to allow for more players than just three. Sure – we’ll get to that. But we also have to think about how to modify the rewards game board.

Modifying the game board could be done in one of two basic ways: with small changes or by resetting the board. Small changes consist of moving one bauble, swapping two, changing the color of one, adding or removing one, etc. For resetting the board I thought of applying some archetypal scenarios to the game. Because I think these are interesting I’ll show you the reward matrix while providing a brief description. Also, to normalize the scoring of the game, I decided that these archetypes will have rewards ranging from 0 to 4 for each player. Thus we can expect points awarded each round to be roughly in the same ballpark. The numbers in each quadrant of the grid are ordered pairs: the first is Red’s reward, and the second Blue’s reward.

Prisoner’s Dilemma

Joint passivity is highly rewarding, but each player has a temptation for aggression. However, joint aggression puts both players at a disadvantage. What a dilemma!

Stag Hunt

Both players are highly rewarded for passivity. Players are only tempted towards aggression if they suspect their opponent will do the same. This is similar to the prisoner’s dilemma but slightly different because the temptation towards aggression is not as strong.

Awkward Sidewalk

This game can be thought of as two people walking towards each other on the sidewalk. If they both stay the course then they have to stop awkwardly. If they both step to the side then it’s awkward again. Both players are only rewarded if one keeps walking while the other steps to the side.

Chicken

Two people drive their cars towards a cliff. The last person to brake wins. The actions can be thought of “brake early” and “wait for the other person to brake”. The chicken brakes early and gets nothing (just shame) while the brave one gets a big reward (fame and praise). But if both players wait for the other to brake then they both drive off the cliff, and neither gets a reward.

There are other archetypal scenarios that I’ve identified and would like to include, each with a different psychological profile and strategy set for the players. I imagine the overall structure of my game is this:

The board starts with a basic archetypal scenario, and the players modify rewards; Red and Blue choose actions, then points are scored. This is repeated twice more before the board is reset to a new game archetype. To throw Green’s baubles onto the board, we can have some way to somewhat randomly place them on the board. This could be done with a deck of cards that provide layouts of the green baubles, or it could be done randomly by rolling dice. That’s not too important to decide right now.

The game mechanics that I want to employ (and discuss just a little bit) are Limited Actions and Unpopular-Action Sweeteners.

Limited Actions

This is not an original concept really; it’s certainly been done before in many cool games such as Agricola, Puerto Rico, Citadels, and Meuterer (to name a few). Basically the players are presented with a limited set of actions and no two players are able to take the same action during a game round.

Unpopular-Action Sweeteners

A few games I’ve played employ something to this effect. If nobody takes an action during one round or turn, then the action is sweetened by placing a reward on it, to be received by the next player to choose that action. Every round that nobody takes the action another reward is placed on it. This way all actions will be attractive at different times and players have to decide at what point a non-strategic action has been sweetened enough to make it worthwhile.

I think it’s fine to employ game mechanics that have been done before. It would be extremely difficult to make a GOOD game that is original in all respects. However, I think it is important to do something novel in your game: perhaps the interaction of tried-and-true mechanics, or perhaps inventing something new. The modification of rewards is something I haven’t seen before, so I’m interested to see where this goes.

Without boring you with TOO many details of my brainstorming, I would say that I’m about ready to put together a rough prototype of the game and start testing it out in practice!

During each stage of the game development process it is key to keep perspective of what the short term goal is. Here’s a map of how to get from zero to a finished game:

1.Concept: Figure out what the game is about.

2.Game Design: How is the game played? What are the rules (game components, goal of the game, etc)?

3.Initial Prototype: Make a playable rough draft of the game.

4.Play-testing: Test out the game to see what works and what doesn’t work. Make changes accordingly. (Repeat this step until you don’t need to make changes anymore.)

5.Publish: Either self-publish or get a publisher to buy your game from you!

An elaboration of the process can be found at the Board Game Designer’s Forum (a fantastic resource for board and card game designers!)

As tempting as it may be to start illustrating the game or adding color (in the general aesthetic sense, not in the purely literal sense), we don’t want to get ahead of ourselves. Right now we need to make a very basic playable prototype. We want to make sure that the game works before we invest time into illustrating it and making it pretty. The prototype doesn’t need to look great; we want to get to the first play test and find out what about the game design is fun and what is clunky and needs to be tweaked or fixed—that is, what ambiguities we didn’t foresee and need to delineate. Moreover, we face the truth: does the game work or is it a dud?

Some games will be duds! Not every game idea we have will be brilliant, and that’s OK. But you need to create and get practice. The more you do that, the more easily you’ll be able to visualize the end in the beginning, to identify a great game concept when it comes.

So let’s make a prototype! My game is pretty simple and doesn’t rely on a lot of fancy game parts, but, even if you imagine a game with bells and whistles, making a prototype is quite doable and shouldn’t cost you much time or money. Here are some of the essentials for a game developer:

Blank Cards

You can use index cards if you want to keep things super simple. If you want your cards to be a little more durable and easier to handle and shuffle, you can buy blank playing cards. At the moment, you can get a box of 500 blank playing cards from Amazon for $7.20 (USD).

In my opinion, this is a must-have for a game designer. Index cards are OK, but to really enjoy the play-testing, you will want cards that feel good to manipulate. You can write with pencil or permanent marker on these cards, and they will get the job done!

Game Boards

You can get some stiff whiteboard from your local craft store and cut it down to size. If you don’t care too much about thickness, however, card stock or even paper will do fine.

Dice

You can probably get by with the average 6-sided die, but you may develop a game that uses dice with 4, 8, 10, 12, or 20 sides. You can buy dice for pretty cheap at game stores or from many online shops. At my local dollar store, they sell a pack of 10 dice (5 white and 5 colored) for $1.

Counters, tokens, money, pawns

For the prototype you can use pretty much anything for game parts, but if you’ll be developing a lot of prototypes, it might be worthwhile to have a little library of game parts. You can buy these from a store like The Game Crafter, if you want them to be fancy, but game parts can be found on the cheap, too! I needed colored tokens, so I went down to Michael’s Arts and Crafts for some bags of rainbow glass gems (they were on sale for $1 per bag!).

Another great option is to buy a big container of colored cubes. Colorful, 1cm cubes are are sold as learning resources to teachers, but they are great as game counters, tokens or whatever (you can do a Google shopping search for “centimeter cubes”). Plastic discs are also sold to teachers as learning aids, and they make great counters or coins and can be used to score points. Translucent and opaque are easily found online.

It didn’t take long to make my prototype. Rather than explaining how I did it, I’ll just show you a photo:

I wanted to keep things super simple for the prototype. I have two sets of Action cards; the top set are the modification actions, which allow players to modify the rewards shown on the game board. The second set are the reward actions, which are how players get points.

Then there are the strategy action cards, a set of X and O for both Blue and Red. (You’ll notice that I used O and X rather than “passive” and “aggressive” – terms I used in my last two posts to describe the players’ action options in my game). These cards allow the Red and Blue players to secretly choose an action and then reveal it simultaneously. Lastly there is a deck of game-board setups for Red/Blue and one for Green, and finally a “Round Leader” card, which is passed around the table to each player so that different people have the opportunity to pick their actions first.

I just needed a few Sharpie pens to put this together. I didn’t do anything with the card backs. You can see how simple it is. Yet this is all I needed to get my friends together and test the game out.

Tune in next time to see how the first play test went and what I learned!

上一篇:如何创造出独特新颖的视觉小说

下一篇:如何为一款异步多人游戏创造AI

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号