有关社交游戏和它们的机遇前沿

作者:Andreas Papathanasis

当我第一次下载《部落战争》时,我在玩了短短15分钟后便删除了游戏。尽管具有可爱的图像和井然有序的界面,但是在与我从小玩到大的一些更有深度的游戏相比,其城市建造与战斗元素都显得太过肤浅了。但是在不到几个月后我又开始玩这款游戏了,而这一次我是带着一个明确的目标:我需要打开部落城堡,如此我便能够加入我的同事不断谈论的那个部落了。我很庆幸自己这么做,因为我已经玩了这款游戏两年多并发现这是一款需要花好几个月时间才能够发现其让人惊讶的深度的有趣游戏。但如果不是因为其社交元素,我应该永远都不会给予这款游戏第二次机会吧。

之后,当我开始为Supercell效劳时,我进一步接触了许多社交活动,即包括游戏内部和游戏外部的活动。而最让我难以忘记的便是极其少量的简单游戏规则却促进并形成了各种社会组织和行为。我花了一整个夏天在不同部落间随机移动着,就为了能够更深入了解推动这款游戏的社交动态元素。我发现了各种“群集”的聚集,他们中的很多人以独特的方式塑造了自己的习惯和规范。我发现自己处在“我的意见就是法律”的强大领导专制式部落中;“我们只是在这里寻求乐趣,远离压力”式的民主状态;以及介于中间的许多复杂的政治变体中。

什么才是真正的社交游戏?

在经历了过去的十年后,Facebook游戏获得了“社交”游戏的头衔,或者说是“社交网络”游戏。“社交图谱”,也就是Facebook用户之间的关系列表被当成是设计游戏中全新独特的社交体验的新前线。通过利用一个人在现实生活中的真正关系,我们便能够围绕着这些关系设计出真正有意义的游戏体验。但是实际发生的情况却是不同的。许多开发者因为被Zynga的早前成功而蒙蔽了双眼,相继涌进了这一领域,并创造出了许多他们自己都不想玩的复制游戏。他们将短期参数奉为真理,并滥用社交图谱去满足自己的需求,而未能提供给玩家任何有价值的内容。所有的这一切都导致了Facebook游戏的衰败。

但是说Facebook游戏的衰败就等于“社交”游戏的衰败却是不合理的。将“社交”游戏等同于Facebook游戏对于我来说便是将“平台”游戏等同于任天堂NES游戏一样荒谬。

社交游戏是指那些会提供至少一种社交结构类型的游戏。

社交结构是指持久,动态,且定义明确的人类玩家群组进行互动并同步或异步参与游戏中有意义的活动。

持久是我的定义中一个重要元素,也是我用于区分社交游戏和多人游戏的关键元素之一。对于我来说社交游戏是在社交结构背景下支持反复的玩家互动的内容。因此只存在一个你将再次寻找随机游戏的对手的大厅的RTS游戏并不属于社交游戏,只能说是一种多人游戏。然而在很多情况下即使游戏中并未提供直接的支持,玩家也可以组成社交结构(游戏邦注:例如在早前的《Quake》中的部落)。如果游戏鼓励更多这样的社交结构,那么这款游戏便会更具有社交性。

公会,联盟和部落是游戏社交结构中最常见的元素。像《魔兽世界》这样的游戏便属于社交游戏,因为公会便是一种社交结构,而袭击也是这样的结构中一种有意义的游戏内部活动。我们可以根据游戏允许朋友间所进行的互动以及我们所定义的“有意义”去判断早前的Facebook游戏是否属于社交游戏。

基于这样的定义,我所感兴趣的下一个问题是:怎样才算一款优秀的社交游戏,我们该如何在未来的社交游戏中进一步完善游戏体验?以下便是我对于这些问题的思考。

一款优秀的社交游戏会使用适当的渠道去发现其他玩家并最大化有意义且持续的社交联系的机会

在那些看到Facebook社交图谱所许下的承诺的人中间有一些杰出的游戏开发者,我认为他们已经在思考问题的根源并尝试着通过使用真实的社交联系去提供给玩家有价值的内容(而不是滥用自私的病毒性传播)。尽管付出了这些努力,我仍未看到任何游戏能够基于开创性方式去使用现实生活中的社交图谱,并提供给玩家前所未有的真正价值。

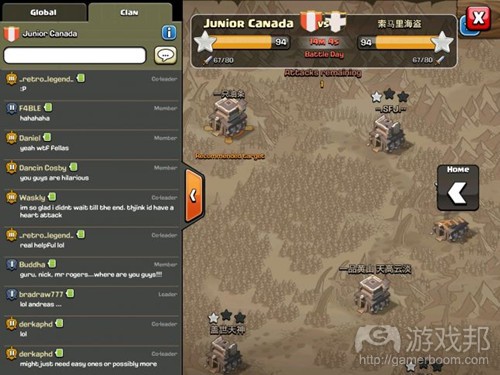

但是这并不意味着我们不能在游戏中使用现实生活中的社交联系去创造价值。不过要做到这点是非常困难的。这同时也意味着并非所有游戏体验都是受益于社交网络联系—-我认为许多游戏体验不仅未能从中获益,同时还会因此受到伤害。以下是来自《帝国同盟》的截图:

我不认识你,但是对于我来说,即使是面对我在现实生活中的朋友,当看到他们基于这种方式侵入一个虚拟的游戏世界时我仍会感到尴尬。例如我的母亲,我的小表妹,我的大学教授,我的会计人员,以及我在会议上见过一次便再也未交流过的人成为了游戏世界中的一份子,那么这不仅不能够为我的游戏体验带来任何帮助,甚至有可能彻底摧毁我的游戏体验。

对于大多数人和游戏来说,最佳游戏内部社交图谱往往都不会与现实生活中的社交图谱具有太多交集。

所以怎样的机制才能有效地在游戏中找到玩家并组成如此最佳游戏内部图谱呢?当然了,这也取决于游戏本身。我们需要思考我们想要提供给玩家怎样的游戏体验,然后遵循更多思考以及如何让他们找到其他人的试验。有些游戏更多地依赖于随机性:你将与其他玩家一起被带到游戏世界中,游戏将提供给你工具与其他人进行交流。你的首个互动对象是取决于你被置于游戏世界的哪里以及那时候你身边会出现什么样的人等随机元素。尽管这是一种合理的开始,但是如果我们能够使用游戏内部或外部工具去帮助玩家更准确地找到能够带给他们更多游戏乐趣的人,结果可能会更好。

现实生活的社交图谱仍然可以作为游戏中第二个发现机制。它可以将我们现实生活中的朋友带到我们所感兴趣的游戏中。简化型的图谱是我迄今为止所看到的最简单,最实用且最有效的应用。在许多游戏中,与我们所认识的人合作或对抗总是比和陌生人游戏更让人兴奋。

一款优秀的社交游戏会为了创造深入,具有意义的情感而平衡地使用社交结构和游戏规则

夏天的时候我访问了《部落战争》中的多个部落,并体验到了最强烈的感受。我为游戏中的决定性战斗准备了军队,并与拥有密切关系的部落成员进行了商讨。虽然我们大不相同,但是我还是很喜欢部落中的一些人,并觉得自己和他们非常靠近。此外,到了这个点时,我们是否应该担心那些赢得了战斗的部落?我和其中的一些玩家制定了一个回战计划并对我们所拥有的机会充满信心。之后,在聊天的过程中我发现自己比想象中更急躁,之前曾与我抗衡过且具有很强好胜心的人加入了部落并把我挤了出去。让我感到惊讶的是我对这一结果非常在意。在接下来一个小时里我一直想着其他比较喜欢我的资深玩家是否会在战争结束前把我带回部落中,如此我便能够赢得胜利(游戏注:我拥有较高的级别,如果我不能作为部落的一份子发动进攻,他们也就没有获胜的机会。对于这款游戏来说,时间投入是赢得战争的关键)。但是我似乎缺了点运气。我并未等到“回归”的信息。这种背叛感非常真实,我真的很受伤。在今后几天里我总是时不时想到这件事,并尝试着回到部落,但却总是遭受到闭门羹。

在像《Neptune’s Pride》和《银河帝国》等多人社交游戏中我也有过相似的遭遇和感受。但是没有一款单人玩家游戏让我体会到这个,包括那些通过故事去呈现这类型感受的游戏。这种感觉强度差别是源于社交游戏中的真实元素,我便是是深受这些游戏事件的影响。在《部落战争》中,我遭到了背叛并被踢出了部落。我非常努力去争取团队在战争中的胜利,但是我却未能得到成员们的感谢,反而遭遇到了驱逐的下场。这是与我在单人玩家游戏故事中所看到的游戏角色遭到背叛完全不同的情景。

Daniel Cook便写过一些关于这种“主要”情感(由发生在你身上的事所引起)与移情式情感(由发生在与你相关的某些人身上的事所引起)间的差异的内容:http://www.lostgarden.com/2011/07/shadow-emotions-and-primary-emotions.html

与Daniel一样,我希望看到我们的产业能够更多地专注于这些“主要”情感,因为它们能够让我们的媒体显得更加独特。没有一部电影或一本书籍能够为我呈现出如此强度的情感。唯一比较接近的,如《Red Wedding》,也是因为在观看的时候我的妻子刚好怀孕9个月。更糟糕的是,如果不能有效地使用来自电影和书籍的故事叙述技巧,我们的互动设置(即玩家对于他们的角色行动的控制)便可能遭遇破坏。《最后的生还者》便是如此,即在最后的游戏强迫我做出多个作为主角的我从未想过的重要决定。如果这是一部电影的话,我会说:“我知道为什么他会那么做,真是个可怜的人,”并且我仍会认为这是一部好电影并继续看下去。但如果面对的是游戏,我会因为它违背了我与角色间的互动而感到生气。

根据我自己的体验,我知道我们能够在游戏中获得“主要”情感,像获得,失去,背叛,绝望,希望等等情感在社交背景下被进一步放大了。这对于游戏开发者来说并不总是好事。通常情况下,这些情感被放大可能导致玩家因为生气或绝望而离开游戏。我便见证了许多玩家因为不能应对游戏中的社交压力而选择离开《部落战争》。不管怎样,我相信如果能够对此进行更多研究,我们便能够把握更多机遇,特别是对于那些不是特别看重大众市场的立基开发者而言。

优秀的社交游戏并不需要复杂性去呈现深度

我发现《部落战争》中的社交体验,也是我在开头的段落中描述的体验并不是什么新内容。优秀的社交游戏(其中也包含许多MMO和MUD)在过去几十年里一直在发展着。而对于我来说真正可以称得上是新鲜事物的是《部落战争》的简单游戏玩法和规则所呈现出的多样性。与《星球大战》(其社交互动的深度主要源自游戏的定位,专业,种族和派系等复杂元素)相比较,在《部落战争》中,简单的功能便足以创造出带有深度的社交互动。在执行《部落战争》功能前后都能够识别到社交互动这一点是非常有启发性的。规则和游戏环境塑造了社交行为,这是我所见证过的相对简单的游戏功能彻底改变社交动态的开放性时刻。这让我不禁开始思考作为游戏开发者的我们还能够在远离复杂性的基础上促进哪些其它行为,创造哪些其它不同的社交游戏体验。

对于我个人而言,这种简单性并不只是适合我玩的这类型游戏。

下一代的社交功能是什么样的?

我想看看我们关于社交游戏的讨论是否能够越过社交网络平台以及像休闲/中核游戏等范围,并开始变成是关于社交结构本身。我们该如何通过在游戏玩法中添加全新或不同的规则和互动而丰富现有的社交结构中的体验?我们该如何创造所有全新且有趣的社交结构,它们会是怎样的?我改如何激励玩家去创造属于自己的非正式结构?为了推动这些游戏内部社交结构中的积极行为,我们该如何管理我们的社区?

为了将讨论引到这一方向,我将提供我在过去几个月所创造的关于社交功能理念的列表。这是作为开发者同时也是玩家的我想要尝试的关于功能的一些半随机想法。我也会列出一些我所试验的游戏。

政府类型

联盟/部落/公会/邻里都是重要的社交结构,我们应该不断寻找更多方法将其变得更有意义,更有趣且更多样化。其中的一种方法便是让部落选择事先确定好的政府,不同的选择能够成就部落所进行的不同交易,部落成员的角色,成员所获得的利益以及部落在游戏中的发展和名声。

例如,有些相似的政府类型可以作用于一些游戏中:君主政体会以更高的税收为代价而赋予参与者更强大的军事力量,而民主政体虽然能够提供更高的资源生产力,但是却拥有较弱的防御力量。政府类型的选择也是部落的身份象征,这能让剩下的世界清楚部落在游戏中所持有的世界观。

整个游戏世界的管理

单一共享游戏可以通过呈现一个非常强大的社交结构去影响整个世界而利用它们的完整世界。例如在每个季节,世界中的前X个玩家可以被分配到参议院,在那里它们可以投票选择一系列可能影响接下来其他游戏玩法发展的决定。不管是对于为了进入参议院而竞争的资深玩家而言,还是对于其他参议院成员所属的其它社交结构来说,这都是有趣且吸引人的设定。

秘密组织

归属于一个“秘密”组织的感受是非常强大的。一款游戏能够通过创造区分于其它特定社交结构的正式或非正式秘密组织而创造独特的情感联系和感受。这些秘密组织将拥有自己的议程(游戏邦注:这可能引出一些与其它社交结构之间有趣的联系)。秘密组织将在特定游戏成员间传播组织的名声,同时也会隐藏其成员的身份。其他非成员如果能够揭露秘密组织的成员便能够获得奖励和工具—-特别是揭露那些地位较高的成员。有些人会作为间谍而潜入秘密组织,这便为游戏增添了一种戏剧感。

角色冲突

在任何社交结构中,角色总是非常重要,它们能够提供给所有成员意义与目的。专注于角色的社交游戏应该:

通过游戏规则将特定社交角色变得更有价值;

通过平衡社交角色而促进多样化的传达(如此就不同技能和兴趣的玩家也能够在不同角色中感受到乐趣);

为每个角色提供有关适当行为的指南(这能够添加一定程度的戏剧效果)

任何让独立个体能够在多个社交结构中扮演一个重要角色的游戏都能够创造出有趣的困境或利益冲突。举个例子来说吧,作为联盟和秘密组织中的一员的玩家可以加入联盟战争并与秘密组织中的成员相抗衡。他们对此会做出怎样的反应呢?

外交

传统的策略游戏总是会呈现出有关玩家的派别与其它AI或者其他玩家所控制的派别之间具有深度的互动。带有支持玩家或相互合作或相互对抗的玩家群组的机制的社交游戏能够通过让两边玩家相互交流,协商战斗/和平/协助/背叛等事宜而获利。在游戏聊天中,交流功能本身就很简单,但是游戏必须支持带有赠予单位,释放单位,交换技能或通过隐藏行动让队友或敌人感到惊讶的能力的适当功能的潜在交涉。支持真实玩家之间的外交功能是一个未得到完全开发的领域,但这却比人类与AI之间的交涉更有发展前途—-因为人类拥有让人惊讶,想起某事,记仇,策划等等能力,而这也是AI永远都不可能做到的。

《Neptune’s Pride》和《Subterfuge》便是两款采取了非常简单的游戏交流方式而提供极具深度的外交功能的游戏。它们的深度是源自专门用于支持外交的游戏内部功能(游戏邦注:如赠送自己的部分武器,直接给予弱势玩家帮助,在战斗中释放敌军英雄)。

特别的群组/社交活动

大多数社交群组都是致力于创造长期的成员联系,所以它们肯定都具有永久性。对于某些游戏来说,基于特别方式创造群组能够以更有趣的方式将某些内容混合在一起。这些临时群组也可以创造联系,特别是它会促成其它永久性社交结构的形成。

让我们以一款基于活动的策略游戏为例。作为特别活动的一部分,特定玩家将加入群组(作为防御者)中并将与更大的群组(攻击者)相抗衡。在活动结束后,不管结果如何,那些喜欢彼此的防御者或攻击者有可能就此产生了永久的联系(例如加入同一个联盟)。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转发,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Social Games and their opportunity frontier

by Andreas Papathanasis

When I first downloaded Clash of Clans, I deleted the game a short 15 minute session later. Despite the cute graphics and sleek interface, the city building and battle elements seemed too shallow compared to the deeper games I grew up playing. It wasn’t until a few months later that I started playing again, with a clearer goal: I needed to unlock the clan castle so I could join the clan my coworkers wouldn’t stop talking about. I’m happy I did, because I’ve being playing for two years and have discovered a fun game that takes many months to expose a surprising amount of depth. But had it not been for the social element, I would never have given that game a second chance.

Later, when I started working for Supercell (the developer of the game), I was further exposed to a fascinating amount of social activity, both inside and outside the game. What stuck the most with me was how a small amount of dead simple game rules encouraged and shaped a wide variety of social organization and behaviors. I spent an entire summer moving somewhat randomly from clan to clan, in an effort to gain a deeper understanding of the social dynamics that drive the game. What I found was a varied collection of “societies”, many of which had structured their own habits and norms in profoundly distinct ways. I found myself in some “my word is the law”, strong leader dictatorship-style clans; in some “we’re just here to have fun, no pressure”-style democracies; and a lot of complex political variations in between.

What, exactly, is a social game?

At the end of the last decade, Facebook games somehow gained the right to be called “social” games, possibly as shorthand for “social network” games. The “social graph”, the vast, interconnected list of relationships between Facebook users, was touted as the next frontier for designing new, unique social experiences in games. By getting access to a person’s real life relationships, the thought went, we can design meaningful game experiences around those relationships. What happened in practice was very different. The vast majority of developers who flooded into the scene were blinded by Zynga’s wild early success, making copycat games they would never want to play themselves, using extremely short-term metrics as their gospel, and abusing the social graph so it served their own virality needs, rather than providing any sort of value to the player. This all led to the well documented decline of Facebook games (http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/203912/with_the_luster_of_social_games_.php).

But to call the decline of Facebook games as a general decline in “social” games is a mistake. Defining a “social” game as a game that is played on Facebook sounds to me a little bit like defining a “platformer” as a game that is played on the Nintendo NES. Since I will be using the term frequently both in this and in future posts, I’d like to clarify what I think of as social games.

A social game is a game that provides at least one type of social structure.

A social structure (within the context of a social game) is a persistent, dynamic, well-defined group of human players that can interact and participate in meaningful in-game activities together, either synchronously or asynchronously.

Persistence is an important element in my definition, and is one of the key elements I use to distinguish between social and merely multiplayer games. A social game to me is something that supports repeated interactions between players in the context of the social structures they belong in. An RTS game with only a lobby where you find random opponents to play with each time is therefore not social, just multiplayer. However, in many cases players can and do form social structures even if not supported directly inside the game (i.e. Clans in the early Quake years). The more such social structures are encouraged (both in game and outside of the game), the more social it is under my definition.

Guilds, Alliances, Clans are the most obvious and common in-game social structures. A game like World of Warcraft is a social game, since a guild is a social structure and raiding is a meaningful in-game activity in the context of that structure. The early Facebook games may or may not be considered social under this definition, depending on the kind of interactions they allow between friends, and our definition of “meaningful”.

With the definition out of the way, the next questions I’m interested in answering are: what makes a *good* social game, and how do we keep improving the experience in future social games? Here are some of my current, still evolving thoughts on these questions.

A good social game uses the appropriate channels to discover other human players in a way that maximizes the chance for meaningful, long-lasting social bonds

Among the people who saw promise in the Facebook social graph were some prominent game developers who I think genuinely thought about the problem, and tried to provide value to the players by using their real life social connections (instead of abusing those connections for self-serving virality). Despite those efforts, I have not seen a game that uses the real life social graph in a ground-breaking way, that provides real, never-before seen value to players (if I missed them, please let me know and I’ll be happy to add such games here).

This does not mean that it is impossible to achieve player value by using their real life social network connections in game. But it does mean it is very hard. It also means that not all game experiences benefit from the social network connection – I actually think that many of them not only don’t benefit, but actually are hurt by them. Here’s a screenshot from Empires and Allies:

I don’t know about you, but for me, even if my real life friends were actually this cool and good looking, I would still find it awkward that they have to invade a fictional game world in this manner. Seeing my mom, my baby cousin, my University professor, my accountant, and that guy I met once at a conference and never really talked to after, being an actual part of the game world, not only does not help my game experience in any way, it kind of ruins it completely. Why are those people there in the first place? They would never be interested in such a game anyway.

For most people and games, the optimal in-game social graph (i.e. the lists of connections to other players that provides the best in game experience) will have little overlap with the real life social graph.

So what would a good primary mechanism be for discovering the players in the game that make up this optimal in-game graph? This, of course, depends on the game itself. We need to think about what experience we are aiming for our players to have in the game, and then follow up with more thought and experimentation on how to enable them to find others that will enable that experience. Some games rely a lot on randomness: you are thrown into the game world, along with everyone else, and given the tools to communicate with them. Who you interact with first will depend a lot on random factors like where you are placed in the world and who happened to be near there at the time. While that’s a reasonable starting point, we may be able to do better with both in-game and out of game tools that assist our players find exactly the kind of people that would enhance their enjoyment of the game.

The real life social graph can still be very useful in-game as a secondary discovery mechanism. It can help which of my real life friends are already playing the game I’m interested in. That reduced form of the graph is the simplest, most practical and useful application of it I’ve seen so far. In many games, teaming up with or fighting against people I already know is more exciting than doing so with strangers.

A good social game uses social structures and game rules in unison, in order to create deep, meaningful, primary emotions

During the summer I was visiting various clans in Clash of Clans, I experienced one of the most intense feelings I had while playing any game. I was preparing my troops for a crucial war attack and chatting up my clan members who I had a rocky relationship with (apparently joining the clan and immediately telling them they’re wrong about what troops are good for defense was a social faux pas). Regardless of our petty differences, I liked some of the members of that clan and considered myself close to them. Besides, shouldn’t we all be worried about the other clan who was, up to that point, winning the war? A couple other guys and myself were formulating a come-back plan and felt pretty good about our chances. And then, during a chat exchange where I must have been slightly more snarky than I should have, the combative elder who was against me joining them in the first place, kicked me out of the clan. To my surprise, that felt extremely devastating. The next hour was filled with wild thoughts that maybe the other elders who liked me a bit more would reverse his decision and invite me back before the war ended, so we could win that thing (I was pretty high level, and because of how wars work in Clash, they had no chance if I wasn’t able to do the attacks as part of the clan. And winning a war is a significant time investment for the Clan, most of them consider it a big deal). But… no such luck. The “Come back” message I was expecting never came. The feeling of betrayal was real, and it stung. I caught myself thinking about the incident for days after, and even tried to return to the clan for a quick chat to get some kind of closure.

I’ve had similar moments and feelings in other multiplayer and social games like Neptune’s Pride and OGame. No single player game has ever come close to generating the same intensity of feelings, including the ones that have carefully crafted stories specifically intended to bring out similar feelings. The difference in intensity is pretty clearly caused by the fact that in the social games, I am personally the one being affected by the game events. In Clash, I myself was betrayed and kicked out of the clan –not my in game avatar. I had worked hard to give the team a fighting chance in the war, and instead of a thank you, I was backstabbed right at the end. This is a completely different thing than seeing your in-game avatar get betrayed in a scripted single player story (even on the ones where you don’t actually see it coming).

Daniel Cook has written on the difference between such “primary” emotions (caused by things that happen to you), and empathy-style emotions (caused by things that happen to someone else you relate with), here:

http://www.lostgarden.com/2011/07/shadow-emotions-and-primary-emotions.html

Like Daniel, I would love to see our industry focus more on these “primary” emotions, because they seem to be something that is making our medium unique. No movie or book has ever reproduced the intensity of such emotions for me. The only thing that came close, the Red Wedding, was likely similarly intense only because it was elevated to a primary emotion because of the fact that my wife was 9 months pregnant at the time I watched it. Worse, the storytelling techniques we seem to be disproportionally borrowing from movies and books can backfire badly in an interactive setting, where the player is supposed to be in control of their agent’s actions. The Last of Us was completely ruined for me because at the end, I was forced into multiple decisions of vast consequence that I would never have done had I been in the protagonist’s shoes. If it was a movie instead, I would go “ah, I get why he did all that, poor guy,” think it was a pretty good movie, and move on. Now, I’ll never forgive the game because it severely violated my sense of agency with that character.

My own experience has been that the “primary” emotions we can experience in games, the feelings of gain, loss, betrayal, desperation, hope, are greatly amplified in a social setting. This is not always a good thing for the game developer. Very often, the emotions are so amplified that people are actively driven away from the game in shame, anger or frustration. I witnessed a lot of people quit Clash of Clans completely because they couldn’t handle the social pressure of having their war attacks watched and judged publicly as they happened. Regardless, I believe more research here is an area of opportunity, especially for niche developers who don’t care about appealing to the mass market. An intense social feeling that may be a turn-off for most players could be the unfulfilled desire for a particular niche.

A good social game does not require complexity to drive depth

The social experience I discovered in Clash of Clans and described in the opening paragraphs was, of course, nothing new. Good social games, many of them MMOs and MUDs, have been growing these kinds of varied societies for decades. But what was news to me, what I was not expecting, was specifically the amount of variety that was enabled by Clash of Clans’ very simple gameplay and rules. Compared, for example, to Star Wars Galaxies, a game where the depth of the social interactions are largely driven by the complexity of the game’s locations, professions, races, factions, in Clash, the very simple Clan Wars feature, was enough to also create social interactions with depth. Being able to observe the kind of social interactions that occurred in clans, before and after the Clan Wars feature was implemented, was very enlightening. Rules and game context shapes social behaviors, and this was my eye opening moment where I witnessed a relatively simple game feature completely change social dynamics. It certainly got me thinking about what other behaviors we can drive as game developers, what other distinct social game experiences we can create, without piling on complexity.

For me personally, this kind of simplicity is not optional in the kinds of games I play.

What will the next generation of social features look like?

I would love to see our discussion of social games move beyond the social network platforms and meaningless terms like casual/mid-core, and start talking about the social structures themselves. How can we enrich the experience in existing social structures, by adding new or different rules and interactions with gameplay? How can we create all new, interesting social structures, and what do they look like? How can we incentivize players to create their own types of informal structures? How can we manage our communities in order to drive positive behavior in these in-game social structures?

In an effort to move the discussion towards that direction, I am providing my list of social feature ideas that I’ve been developing over the past few months. These are semi-random thoughts on features I would personally like to experiment with, both as a developer and as a gamer. Where applicable I list games that I think have adopted these features to some extent. I’m sure I’ve missed many, so please let me know of other ones you know.

Government Types

Alliances/clans/guilds/neighborhoods are a key social structure and we should always keep looking for ways to make them more meaningful, interesting, and diverse. One such way could be to allow the clan to choose between predefined governments, with different options allowing different trade-offs on how the clan is operated, what roles it offers its members, what kind of benefits the members get, and how the clan progresses and gathers fame within the game.

For example, familiar government types could work in some games: Monarchy could boost the participant’s army strength at the cost of higher taxes, or democracy could allow higher resource production but weaker defenses. The choice of government type could also be a status symbol for the clan, telling the rest of the world what the clan’s worldview is in the game.

Governance of the entire game world

Single-shard games can take advantage of their non-compartmentalized world by allowing a very powerful Social Structure that can affect the entire world for all other players. As a very simple example, each season, the top X players in the world could be assigned to the Senate, where they can vote among a set of proposed boosts that will apply to every single player in the game for the next Y amount of time. This is interesting and engaging not only for the top players who compete to enter the Senate, but also for the other social structures the Senate members belong to (other players or groups will want to approach Senators and influence their decision, perhaps via incentives the game allows them to offer).

Secret Societies

The feeling of belonging to a “secret” organization is very powerful. A game could evoke very unique bonds and excitement by allowing the creation of either formal or informal secret societies that are separate from other regular social structures. These secret societies could have their own agenda (which could lead to some very interesting combinations with other social structures, i.e. the Senate discussed above). The Secret Society would seek to spread fame of the organization among regular game members, while concealing the identity of its members. Other non-members could be given the incentives and tools to try and expose the secret society members – especially high ranking members. Some would try to infiltrate the Secret Society in order to spy on them, adding to the overall drama and excitement.

Role Conflict

Roles are important in any social structure, as they give meaning and purpose to all members of the structure. A social game focusing on roles should:

reinforce certain social roles by making them more desirable via game rules;

promote diversity by making social roles balanced (so people of different skills and interests can be happy in different roles); and

provide guidelines on appropriate behavior for each role (even though it’s sometimes perfectly acceptable for some of those to be broken, this just adds to social drama)

Any game that allows an individual to hold an important role on multiple social structures can create interesting dilemmas/conflict of interest type situations. For instance, a player who is part of both an Alliance and a Secret Society could be thrown in Alliance War against a member of the Secret Society. How will they react?

Diplomacy

Traditional 4x strategy games owe a lot of their depth to interactions between the player’s faction and other AI- or player-controlled factions. Social games with mechanics that support players or groups of players playing cooperatively or against other players/groups may benefit from the ability for both sides to be able to communicate with each other and negotiate terms for war/peace/assistance/betrayal. The communication functionality itself could be as simple as in game chat, but the game must support potential negotiations with the appropriate features such as donating units, releasing captured units, exchanging tech, or ability to surprise allies and enemies with concealed actions. Supporting such diplomacy features between actual players is a huge untapped area and vastly more promising than diplomacy between a human and an AI – humans have the ability to surprise, remember, hold grudges, scheme, in a way no AI will achieve any time soon.

Neptune’s Pride and Subterfuge are two games that provide extremely deep diplomacy using an extremely bare-bones in game chat screen. The depth comes from in-game features designed to support diplomacy (i.e. gifting part of your army, directly funding weaker players, freeing enemy heroes taken prisoner in battle).

Ad-hoc groups/Social Events

Most social groups are intended to create long-lasting bonds between their members, and so naturally are intended to be permanent. For some kinds of games though, creating groups in an ad-hoc way (perhaps as part of an event) could mix things up in an interesting and fun way. These temporary groups can also create bonds, especially if it leads to the formation of another, permanent social structure.

For example, imagine an event-based strategy game. As part of an opt-in event, certain players are put in a group (Defenders) and are required to defend their bases against a much larger group (Attackers). After the end of the event, and regardless of the outcome, it’s likely some of the defenders or attackers who liked each other will form separate, permanent bonds (i.e. join the same alliance).

I’d love to hear more from other developers on the subject. What are your favorite social games? What’s the most exciting moments you’ve experienced as part of a social structure? What are the areas you’d like to see further experimentation in social games?(source:gamasutra)

上一篇:关于手机营销自动化策略的6大步骤

下一篇:阐述设备规格对游戏设计的重要性

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号