关于电子游戏中的暴力(二):基于主题的游戏设计

作者:Keith Burgun

在第一部分文章中,我讨论了对于歌颂暴力的描述所带有的文化和信息传达问题。而在第二部分中,我将讨论基于暴力主题和设置所引起的无意识的规则集问题。

我并不提倡“从主题开始”—-你当然也不能从说着“3个英勇的战士进入Grundendo森林去寻找被施了魔法的方尖碑并消灭邪恶的Sorcerer Johns”这样的内容开始设计一款游戏。这并不是一个游戏设计概念,我认为大多数设计师应该清楚这点。如此你不仅不能传达任何基于规则的理念,同时也限制了自己创造规则的能力。从根本上来看,这是一种逆向做法:主题是我们用于规则中(以帮助传达)的比喻。从主题开始进行游戏设计就像是从绘制封面开始写小说一样。

照这样说,我们至少可以使用一些较小的主题,特别是在游戏的早期设计阶段。如果你与大多数设计师一样,你可能会从某种特定的游戏“类型”开始,可能就像“这与《高级战争》一样,但是……”,或者这是一款“Rogue游戏,但是……”。如果将这作为“基础”,你将围绕着它开始进行设计。如果你是一名优秀的设计师,你可能会解决许多问题,即包括改变这些系统,但是最初的类型或游戏仍然是你的基础。

今天,我想要在此谈谈基于暴力主题进行设计的消极影响。

直接性

当互动具有直接性时,《最终幻想III》至少还是有趣的。想象如果在一款像《Puerto Rico》的角色选择游戏中,存在一个非常简单的行动,即“获得3个胜利点数”。或者如果在《英雄联盟》中,存在一种只是提供给你金币和体验的行为能力。或者在《星际争霸》中存在一些你可以通过摧毁1/3敌人的武器和基地而进行建造的昂贵建筑。

你可以潜在地平衡这三个例子,如此便不会出现哪个例子比其它例子更突出。即使得到了平衡,它们仍然是你在游戏中能够做的最不有趣的事。选择使用这类游戏元素的玩家将拥有比其他玩家更加糟糕的游戏体验。

直接性并不有趣的原因是它允许玩家根据自己的需求穿过(因此便能理解)系统。让我举些例子进行说明。

在《Puerto Rico》中,你需要获得种植园,一个厂房,并使用工匠行动和队长行动,基于这种方式你将不会浪费资源或提供给敌人太多帮助。基于+3的胜利点数行动,你便可以忽视所有的其它内容而只是获得3个胜利点数。

在《英雄联盟》中,你需要清除一波又一波的小兵,打败对立盟主,最重要的是你需要建立一支带有策略的团队从而让自己占上风。而现在你可以绕过所有的这些内容,并尽可能地传达你的体验能力。

在《星际争霸》中,你需要与敌人的单位类型相抗衡,你需要考虑单位在战斗中的战术定位,你需要纠结什么时候才是最佳攻击时刻。基于《星际争霸》的超级建筑,你可以在创建超级建筑的时候延迟游戏,并在完成建造之后发动攻击。

所有的这三种能力都能够进行平衡,即让使用他们的玩家可以获得与未使用的玩家同样比例的时间。解决平衡问题并不等于解决有趣的逆差问题。我们很难去平衡一些非常直接以及一些非常间接的内容。

当然了,这些例子都有点夸大了,这只是为了突出我的观点。实际上,游戏中有很多元素是“更直接”或“较不直接”。在《Puerto Rico》中,获取建造者的策略比寻求运输策略更加直接。在《英雄联盟》中,仍然由许多角色拥有黄金/升级获得的点数或者能够创造更多伤害/处理更多伤害的“类固醇”行动。在《星际争霸》中,存在一些“直冲”游戏,即让玩家为了在一些有趣的内容出现前结束游戏而快速执行一系列的命令。

一些在某种程度上是“直接”的内容其实绕过了系统。表面上,你的系统应该具有乐趣,所以任何任何绕过系统的内容都不能给玩家体验带去帮助。不幸的是,玩家的动机主要是为了获取胜利。他并没有责任去确保自己能够获得游戏的最佳体验—-这应该是你的责任。

另一方面,当游戏行动需要利用更多游戏资源,行动和变量时,游戏行动便是“间接的”。《超级食肉男孩》的战斗不如《街头霸王》的直接,因为在《超级食肉男孩》中,你的定位在游戏关卡中很重要—-比起在舞台边缘,在舞台中间位置撞击了别人更难打败对方。然而在《街头霸王》中,关卡中的定位不具有轴承关系;你只需要将对方的生命值降至0便可,不管你是在哪里做到这点。如果更多游戏变量与行动相联系,那么游戏的直接性便更低。

你可能已经注意到了,并非我所列举的所有“直接的”例子都是暴利游戏。我要声明的是并非“所有直接的游戏玩法互动都是以暴利为主题,”而是“大多数以暴利为主题的游戏玩法互动都是直接的。”

消除复杂性

作为游戏设计的“基础”,其它关于暴力的问题总是倾向于基于“消除”概念。就像“杀戮”从内在看来就是关于有效且彻底地消除游戏中的物体。

当然了,我并不是说“一个优秀的游戏设计便是永远不会消除游戏领域中的元素。”当根本假设是互动导致消除(“死亡”)时,我们将面对太多消除内容。

为了进一步说明,让我们想象一款《宇宙巡航机》类型的射击游戏。如果在一个空荡荡的屏幕上只出现一只怪物,并且它向你发射一枚子弹,那么我们可以说这是这一系统最小的乐趣。另一方面,让我们着眼于截图中所传达的情境。

在《宇宙巡航机》的最有趣的系统中,你可能需要在任何时刻考虑各种内容。环境需要配合它,并将一些区域变成是难以靠近的。你已经获得一些补给能源,最重要的是,屏幕上会出现一些“怪物”对你造成危险(游戏邦注:可能会阻挡你的道路并向你发射子弹)。像该前往那里,该向什么东西射击以及该专注于什么都不是非常有趣,因为所有的这些变量将同时聚集在一起。

如果这些怪物不在,我们将突然出现在一个非常无趣的游戏领域。然而在《宇宙巡航机》中,消灭怪物是玩家所期待的。基于这种方式,玩家将通过消灭威胁而降低自己的游戏体验的乐趣。

实际上,这也是“权利幻想”概念(歌颂暴力主题的核心内容)与优秀游戏的需求间存在的直接矛盾。权利幻想指的是有时候提供给玩家一些非常具有破坏性的武器,让他们能够清除屏幕上的全部障碍。当然了,让他们清楚屏幕上的障碍便意味着会导致游戏变得无趣。这就像是进入一个作弊码一样。

当然了,游戏关于“威胁被消除”的解决方法便是不断创造新怪物到游戏中。它们会出现在屏幕上,并且大多数情况下我们都会尝试着尽快地分派它们。许多怪物会在玩家真正看到他们之前便被消灭掉。

因为我们的主要行动是“消除”,所以我们将只剩下一个为了让我们消除内容而不断创造出新事物的系统。从根本上看,如果我们想要深入的游戏玩法,这便不是一种有效的氛围。

创造复杂性

让我们从另一个角度着眼于《Puerto Rico》。即面向那些不知道《Puerto Rico》是一款基于欧洲的“角色选择”桌面游戏的人。在这款游戏中,你们将轮流选择一个角色,如建造者(允许你花钱去建造一座建筑物),工匠(允许你在自己的种植园制作产品)或船长(允许你为了获得胜利点数而运输已经制作好的产品)。

尽管游戏目标只是“快速获得最多胜利点数”,但是游戏中的情境却会变得非常复杂且有趣。现在你可能需要制作产品,但如果你这么做,你之后的人便能够运输产品,如果他这么做,他将填满你运输产品时所需要的船的空间,从而导致你的产品不能运输。同样地,假设你在制作产品,而玩家3将制作一件有价值的咖啡产品,你知道他将在市场上销售自己的产品并赚大钱,但是你却做不到这点。如果他那么做,而你创建了一间办公室,这便意味着你也能够有效地销售自己的咖啡,你将拥有一个小小的市场。

这里的要点在于,贯穿游戏,玩家正在以建筑,种植园,工人和产品等形式往游戏中添加复杂性。随着游戏的发展,问题将变得更加复杂且有趣。当然了,“最复杂”并不一定意味着“最有趣”,但游戏需要变得足够复杂才能够挑战人们的大脑并让他们真正觉得有趣。

此外,游戏是逐渐呈现出复杂性,所以当你在游戏的时候,你也能够轻松地搞清楚发生了什么。这点非常重要—-游戏不能在一开始就非常复杂。玩家一次只能摄取一定量的新信息。所以到达一个较高复杂点的有效方法便是基于游戏回合进行叠加创造。

《Puerto Rico》并未拥有任何形式的“攻击”或“破坏”。如果它这么做,游戏将倒退回一种简单且无趣的内容。

关于这一规则是否存在例外?当然了。象棋就是一款基于“消除”机制的游戏。因为在任何时候象棋中的游戏状态都是非常复杂的—-对于大多数玩家来说都太过复杂。类似但且不那么复杂的战斗游戏如果依赖于消除机制的话将很快被玩家解决(需要设计师去执行输出随机性或其它即时且模糊的资源去弥补它)。

电子游戏转义

许多经典的电子游戏设计转义都是具有内在的直接性且倾向于消除复杂性。因此我们应该多加警惕。

射击游戏应该是最常见的暴力电子游戏转义。其实它只是关于“朝着连续空间发射子弹而已。当它撞击了一个目标,该目标将被摧毁(游戏邦注:有时候是在多次撞击之后)。”这描述了许多电子游戏的核心内容,这也是一种疯狂的想法。从《太空入侵者》和《Ikaruga》等2D射击游戏到《反恐精英》或《Battlezone》等3D游戏,这一核心机制在游戏中所占据的空间真的非常巨大。

如果你添加了“用剑刺破/划破”机制,我想所有玩家都不会感到惊讶,因为我们正在描述着所有电子游戏所具有的80%–90%的内容。

这里存在许多原因:依赖幻想模拟而不是互动系统设计的一致理论;看到计算机追踪许多子弹的技术画面;或者只是产业的“童星综合症”。不管怎么说这都是一个在50年间从“不存在”发展成“世界上最大的文化/产业现象”的产业和学科。即使我们继续基于《太空入侵者》和《超级玛丽兄弟》去看待“电子游戏”也是可行的。

然而我们使用这么多“射击游戏”的原因其实是不相干的。它们只能够解释情境而不能作为辩护理由。这里的要点在于,这是我们应该改变的内容。我们不应该基于主题假设任何内容,如果我们要假设某些内容,它应该让我们远离基于暴力的主题。

德国的欧洲游戏

如果你在思考游戏基于主题和机制存在的完整可能性,你会发现这种可能性是无限大的。你可以创造一款关于在巨大的几何形状周围推水的游戏,即以浴缸中的橡胶玩具为主题。你可以创造一款关于画线去占领区域的游戏,并以激光秀为主题。基于这些主题,你可以创造无数不同的核心机制。

对于我来说,那些认为我们从根本上“明确了游戏类型,即塔防游戏,平台游戏,第一人称射击游戏等等”的人来说这是一种目光短浅的看法。

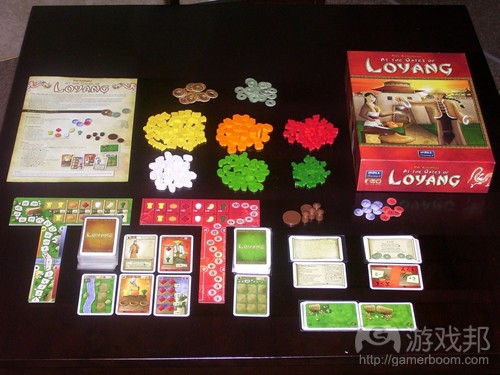

对于那些有这种想法的人,我会建议他们深入研究设计师桌面游戏的世界。也就是欧洲游戏。或者更具体的说应该是德国的欧洲游戏。

像Reiner Knizia,Uwe Rosenberg,Andreyas Seyfarth等等设计师都是未做一些不利的假设而开始设计游戏。当然了,他们也有自己的转义,他们有时候会基于以前的游戏去创造自己的游戏,但通常情况下,这个世界比数字游戏世界更能推动他们去探索可能性。

除了拥有许多世界上最伟大的游戏设计师外,德国同时也是“桌面游戏圣地”—-Internationale Spieltage SPIEL,世界上最大的桌面游戏大会便是在埃森市举办,并且每年会吸引15万的参与者。

许多人都在思考德国聚集着许多伟大的桌面设计师的原因。说实话,这具有许多原因。但是有一点打击到我了,那就是是德国禁止歌颂暴力。

我想要再次强调之前说过的:我认为这是错的。我非常反对禁止媒体歌颂暴力的法律。即便如此,我们仍然能够看到拥有这一法律的效果。不管原因是什么,德国人都不能依赖于“射击”和“鞭打”机制,所以他们只是重新进行思考。

我们并不需要拥有同样效果的法律。我们,也就是整个世界,包括德国人都是大人了。我们能够理解不断依赖于暴力所带来的消极影响,但是我们也能够调整自己的行为。

结论

我希望未来我们能够更加认真对待我们置于媒体上的信息,并能够创造出更具创造性和乐趣的游戏。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转功,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Violence, Part 2: Game Design Ramifications

by Keith Burgun

In Part 1, I discussed the cultural and messaging problems involved with portraying the glorification of violence. In this part, I’ll be discussing the mechanical ruleset issues that tend to arise as a result of working with violent themes and settings.

I do not advocate “starting with theme” – you should certainly not start a game design out by saying something like “Three heroic warriors travel into the Grundendo Forest to find the Enchanted Obelisk and destroy the evil villain Sorcerer Johns.” This is not a game design concept, and I think most designers understand that. You’re not only failing to communicate any mechanical, rule-based idea, but you’re also restricting your ability to develop rules by the metaphor. Essentially, it’s working backwards: theme is the metaphor we apply to our rules to help communicate them. Starting a game design with a theme is like starting a novel with painting the cover artwork.

With that said, it’s useful to at least use small, loose bits of theme, especially during a game’s earliest design phases. If you’re like most designers, you probably start with a “genre” of some kind or a specific game – perhaps something like, “it’s like Advance Wars, but _____”, or it’s a “Rogue-like, but _____”. With that as your “base”, you work out from there. If you’re a good designer, you probably do a lot of problem solving, which involves a lot of dramatic changes to those systems, but you still have that original genre or game as a base.

Today, I want to talk about the negative ramifications of working with a violence-themed base.

Directness

Final Fantasy III (english translation)-2-fullGames are at their least interesting when interactions are direct. Imagine if in a role-selection game like Puerto Rico, there was an action that was simply, “take three victory points”. Or if in League of Legends, there was an active ability that just gave you gold and experience. Or if in Starcraft, there was some expensive building you could build that destroyed 1/3 of the opponent’s army and base when you built it.

You could potentially balance all three of those examples, so that they weren’t more or less effective overall than other options. Even if they were balanced, though, they would still be the least interesting thing you could do in the game. Players who chose to use those game elements would be having a distinctly worse experience than players who did not.

The reason directness is uninteresting is because it allows the player to circumvent his need to traverse – and therefore understand – the system. Allow me to give a few examples to help demonstrate what I mean.

Puerto Rico – Normally, you have to get plantations, a processing building, use the craftsman action and the captain action, all timed in such a way that you don’t end up wasting resources or helping your opponents too much. With the +3 VP action, you can ignore all of that and just get the three victory points.

League of Legends – Normally, you have to clear minion waves, defeat enemy champions, and most importantly, set up strategic team plays to gain an upper hand. Now, you can circumvent all of that, turtle up a bit, and spam the Gold and Experience ability as much as possible.

Starcraft – Normally, you have to counter the opponent’s unit types, you have to be concerned with the tactical positioning of units in battle, you have to worry about exactly when the right moment is to attack. With the Starcraft Super-Building, you can just delay the game while you build the super-building, then attack right after it’s built.

All three of these abilities could, again, be balanced as such that players who use them win a similar percentage of the time as players who don’t. Fixing the balance problem does not fix the interesting-ness deficit. It’s worth noting, though, that it’s notoriously difficult to balance something very direct against something very indirect.

Of course, these examples are all ridiculously exaggerated in order to highlight my point. In reality, there are elements in all games that are “more direct” or “less direct”. In Puerto Rico, going for a Builder strategy is a lot more direct than going for a shipping strategy. In League of Legends, there are still characters that have flat gold/stat bonus passives or “steroid” moves that simply Do More Damage / Deal More Damage. In Starcraft, there are “rushdown” plays that involve doing a series of rote commands very quickly in order to end the game before anything interesting has a chance of happening.

Something is “direct” to the extent that it circumvents the system. Ostensibly, your system should be interesting, so anything that circumvents interaction with it is bad for the player experience. Unfortunately, the player is – and should be – primarily motivated by trying to actually win. It is not his responsibility to make sure that he’s getting the optimal experience out of the game – it’s yours.

On the other hand, a game action is “indirect” when it needs to utilize more of the game resources, actions and variables in order to work. Super Smash Bros. combat is less direct than Street Fighter’s, because in Super Smash Bros. your positioning on the level matters – if you hit someone hard in the middle of the stage, you’re less likely to defeat them than if it’s near the edge. Whereas in Street Fighter the positioning on the level has no bearing; you just have to get their health points to zero, regardless of where you are. The more game variables that tie into the action, the less “direct” it is.

As you’ve probably noticed, not all of my “direct” examples are necessarily violent. My claim is not “all direct gameplay interactions are violence-themed”, but rather, “most violence-themed gameplay interactions are direct”.

Removal of Complexity

The other problem with violence as a “base” for a game design is that it almost always tends to be based on the concept of “removal”. Killing, inherently, is about effectively removing objects from the game space entirely.

Of course, I’m not saying that “a good game design is one where elements are never removed from the game space”. However, when the basic assumption is that interaction leads to removal (“death”), we end up with way too much of it.

To demonstrate, imagine a Gradius-style shooter game. If just one monster flies onto an empty, open screen, and it shoots a single bullet at you, it’s probably safe to say that that’s about the least interesting such a system gets. On the other hand, take a situation such as the one depicted in this screenshot.

Gradius, with some visual aids to help those who might not have grown up with it just what in God’s name it is they’re looking at here

At Gradius‘ most-interesting, you might have numerous things to consider at any given moment. The environment has a shape to it, making some areas unavailable. You’ve got some powerups that behave in a certain way that you need to compensate for (such as “Option”, little orbs that follow you around doing what you do, or missiles that fly in a diagonal direction). Perhaps most importantly, there are “monsters” on-screen that threaten you (both as obstacles and by firing projectiles at you). The decisions about where to go, what to shoot, what to focus on are only even a little bit interesting because of all of these variables coming together at the same time.

If those monsters weren’t there, then we’d suddenly be in a dramatically less interesting game space. And yet, removing them is exactly what the player is expected to do in Gradius. In a way, the player makes his own game experience less interesting by removing the threats.

This is, in fact, where the “power fantasy” concept – so central to violence-glorifying themes – directly conflicts with the needs of a good game. The power fantasy says, give the player some hugely devastating weaponry sometime and let him clear the entire screen. Of course, letting them actually clear the screen means making the game a lot more boring. It’s quite like entering in a cheat code.

Of course, the game’s solution to the problem of “threats getting removed” is to just keep feeding new monsters into the game. They come on screen, and for the most part, we try to dispatch them as quickly as we can. Many monsters are destroyed before they even become visible.

Since our primary action is “removal”, what we’re left with is a system that’s based on constantly rolling in new things for us to remove. At a fundamental level, this is not a healthy atmosphere if we want deep gameplay.

Building Complexity

On the other end of the spectrum, let’s take another look at Puerto Rico. For those who may not know Puerto Rico is a “role selection” Euro boardgame. In the game, you take turns choosing a role, such as Builder (allows you to spend money to build a building), Craftsman (allows you to produce goods from your manned plantations) or Captain (allows you to ship goods you’ve already produced for Victory Points).

While the object of the game is a simple “race to obtain the most Victory Points”, the situations that occur during the game get quite complex and interesting. You might need to produce goods right now, but if you do so, the guy after you will be able to ship, and if he does that, he’ll fill up the ship you need to use and your goods will get wasted. Also if you produce, Player 3 will produce a valuable Coffee good, and you know he’s going to sell it on the market and make a ton of money, and you can’t have that. Although, if he does that, you did build an Office, which means you’ll be able to sell your Coffee good as well, and you have a Small Market… so maybe it’s still worth it?

The point is that throughout the game, players are adding complexity to their boards in the form of buildings, plantations, workers and goods. As the game goes on, the problems become more complex, nuanced, and interesting. Of course, “more complex” does not necessarily mean “more interesting”, but a game does need to be pretty complex to really challenge a human brain and become interesting.

The other thing is, it introduces complexity piece by piece, so while you’re playing it’s actually quite easy to keep track of what’s going on. This is pretty important – a game can’t just start out super complicated. Players can only intake so much new information at a time. So the smart way to reach a point of high complexity is to build up to it throughout a game session.

Puerto Rico does not have any form of “attacking” or “destruction”. If it did, the game would be effectively taking steps backward throughout, towards a less-complex and less-potentially-interesting situation.

Are there exceptions to this rule? Of course there are. Look no further than Chess for a game that is reliant on “removal”, yet still works. This is quite likely because the game state at any given time in Chess is incredibly complex – arguably, far too complex for most players. A similar war-game that was less inherently complex might become quickly solvable if it relies on removal (which might lead a designer to implement output randomness or other instant ambiguity sauces to make up for it).

Videogame Tropes

Many of the classic videogame design tropes are both inherently direct and tend to remove complexity. Therefore, we should be wary of them.

Shooting is probably the number one most commonly seen violent videogame trope. Ultimately, it’s just “launching a projectile, usually ballistic, in a direction, usually on continuous space. When it hits an object, that object is destroyed (sometimes after multiple hits)”. That describes the core of so many videogames, it’s kind of crazy to even think about. From 2D shooters like Space Invaders and Ikaruga to 3D ones like Counter-Strike or Battlezone, the amount of space this one core mechanism takes up in games in general is massive.

If you add in “punching/slashing with a sword”, I don’t think anyone would be surprised if we were now describing 80-90% of all videogames ever made.

There are a lot of reasons for this: the reliance on fantasy simulation in lieu of coherent theory for interactive systems design; the technological spectacle of seeing a computer keep track of hundreds of bullets; or simply the industry’s “child actor syndrome”. This is, after all, an industry and a discipline that went from “non-existent” to “the world’s biggest cultural/industrial phenomenon” in under 50 years. It makes some sense that we continue to think of “videogames” in terms of Space Invaders and Super Mario Bros.

The reasons for why we use so much “shooting” are irrelevant, however. They can only be explanations for the situation, not justifications. The point is, this is something that we should change. We shouldn’t be presuming anything with regards to theme, although if we do have to presume something, it would behoove us to lean away from violence-based themes.

German Eurogames

If you think for a moment about the full range of possibilities that could exist in terms of theme and mechanisms for games, it’s almost infinitely large. You could have a game that’s about pushing water around between large geometric shapes, themed as rubber toys in a bathtub. You could have a game that’s about drawing lines to take territory, and theme it like some kind of laser light show. There are a billion core mechanisms out there and a variety of ways to effectively theme each of them.

It is incredible to me that some are so small-minded as to think that we’ve basically “got the genres figured out, ya got yer tower defense, yer jumpy platformer, yer FPS, and a few other things, but that’s it!”

To people who feel that way, I recommend some serious research into the world of designer boardgames. Specifically, Eurogames. Even more specifically, German Eurogames.

Designers like Reiner Knizia, Uwe Rosenberg, Andreyas Seyfarth and others have a pattern of really starting without a bunch of unhealthy assumptions. Sure, they do have their own tropes, and they do sometimes make games that build off of a previous game, but in general, this world is much, much more likely to actually explore other possibilities than the digital game world is.

Besides calling many of the world’s greatest game designers its citizens, Germany is also home to “boardgame Mecca” – the Internationale Spieltage SPIEL, the largest boardgame convention in the world is held in Essen, and brings roughly 150,000 people to its doors every year

Many have pondered about the reasons for why Germany became such a hotspot for great boardgame designers. To be fair, there are a lot of reasons for why this could have happened. However, one reason that does strike me is the fact that the glorification of violence is banned in Germany.

Now, I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: I think that’s wrong. I am staunchly opposed to laws that prohibit media that glorifies violence. With that said, though, we can still take note of the effect of having this law in place. Regardless of the cause, the German people were unable to rely on “shooting” and “slashing”, and so they had to start actually thinking.

We don’t need a law to get a similar effect. We – and by we, I mean the entire world, including Germany, are big boys and girls. We can simply understand the negative ramifications of our constant reliance on violence, and we can adjust our behavior.

Conclusion

I’m looking forward to a future in which we’re more conscientious about the messages we’re putting forward in our media, and I’m also looking forward to games that are patently more novel and interesting.

Can a smart designer who understands the classic pitfalls of violent games avoid those pitfalls while still making a violence-themed game? Yes. Should they? Only if I haven’t convinced them with Part 1.

Remember that I’m not trying to force anyone to do anything. I’m trying to persuade. If my work fails to persuade you, that’s OK. Let me know why in the comments, and thanks for reading!(source:keithburgun)