万字长文,从产品设计角度阐述游戏制作的10个问题

作者:Mark Rosewater

我经常提到Brian Tinsman对于创新的追求。这种追求不仅体现在的他的Magic游戏设计,甚至贯穿于他所从事的任何一项工作中。Brian曾经针对Wizards of the Coast(游戏邦注 :位于西雅图Emerald City的游戏公司)研发部门所具有的全部资源进行了深入思考,并发现那些杰出的Magic游戏设计创意都是源自于这里(游戏邦注:他们不但开发了《龙与地 下城》和《决斗王》这两款大型游戏,也创造了许多有趣的小游戏)。是否有哪一种方法能够帮助我们更好地集思广益?

最终结果便是组成了一个小组并例行参加两周一次的会议,即Brian口中的“游戏设计最佳实践团队”。研发部门的每一名设计者都受到了邀请。在每一次回忆中,不同的设计者将 会选择任何与设计相关的主题,并一起花费数个小时讨论这个话题。而今天我要着重讨论的话题是我在第一次会议中所选择的主题内容。

Brain和Braun

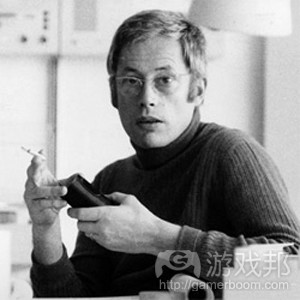

我们那次的讨论始终围绕着Dieter Rams提出的游戏设计10大原则。让我们回到过去,从那天讨论的起始主题:“谁是Dieter Rams”开始说起。根据维基百科的解释:

Dieter Rams(from wizards)

Dieter Rams(在1932年5月20日出生于德国黑森邦威斯巴登市)为著名德国工业设计师,与德国家电制造商Braun和机能主义设计学派有着很密切的关系。

为何家用电器产品的设计者会与游戏设计扯上关系?可能不只少数人在思考这个问题。为了更好地理解Dieter Rams与我自己,作为游戏设计者的这种身份之间的关系,我将在以下 列出我们间的几大联系:

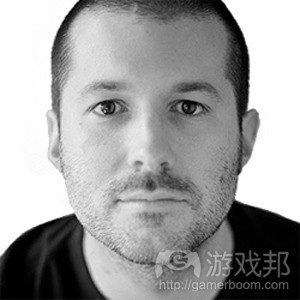

下图是谁?他是Jonathan Ive,也是一名家电设计师,并且正效力于一家非常出名的公司,知名度甚至超越Braun,也就是苹果。

Jonathan Ive(from wizards)

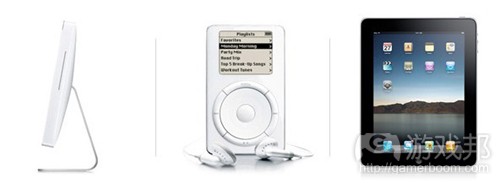

Jonathan Ive是苹果工业设计部资深副总裁,但是比起他高高在上的地位,更让我印象深刻的还是他的设计才能。以下的产品你们应该不会陌生吧,这些都是Jonathan Ive杰出的 设计:

Jonathan Ive’s designs(from wizards)

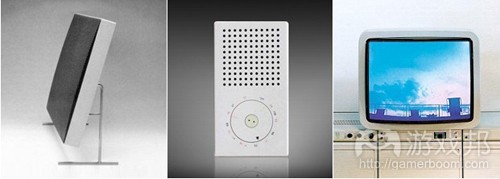

Jonathan Ive与Dieter Rams有何交集?让我们看看Dieter Rams的一些作品:

Dieter Rams’s designs(from wizards)

很多人认为Dieter Rams作为一名出色的工业设计师,在很多方面影响着Jonathan Ive的设计。而我认为Jonathan Ive是当代最杰出的工业设计师之一,所以我很乐意能够遵循着他 的脚步一直往前走。

我可是一名纸牌游戏设计者,这与工业设计又有何关联?我的答案是“非常有关系”,因为我认为设计就是设计,无关任何设计产物。为了成为一名更为杰出的设计者,我不能只 懂得游戏设计或者纸牌设计,还应该理解广义的设计理念。

今天我们要讨论的话题是关于Dieter Rams的游戏设计10大原则,以及这10大原则是如何在游戏设计以及Magic游戏设计中加以应用。如果你真心对游戏设计感兴趣,那么一定不要 错过这些内容。

首先我们来看看这10大设计原则:

1)好设计具有创造性。

2)好设计具有实用性。

3)好设计具有美感。

4)好设计有助于我们了解产品。

5)好设计不会很高调。

6)好设计是诚信。

7)好设计经久耐用。

8)好设计不放过任何一个细节。

9)好设计重视与环境相协调。

10)好设计就是尽量避免“设计”。

好好掂量这10大原则,你会发现它们的确有一定的价值。以下我将一一分析这些原则。

1)好设计具有创造性。

首先我们必须先来说说创造性。怎样才能具有创造性?

1.你的创造必须是新的,或者至少是某一个领域中的一个新理念。如果你想在设计中达到创新,那么你就必须引进一些新元素。

2.这种创造性必须引起一些证明的改变。不只是新颖就足够了。新的改变必须能够引起设计过程的变化,并推动设计的发展。

3.创造性必须具有价值。也就是说这种改变必须能为设计带来一些具有价值的新鲜内容。

4.它也具有一些消极影响或者破坏性。很多时候随着新事物的引进,我们也必须淘汰一些旧事物。

5.它会导致一定的风险。改变总是需要一定的代价。

我想Ram在这里真正想要表达的是设计的真义在于前进。也就是你想要挑战一些已知的事物并采取一些潜在的方法去完善设计的每一个步骤。好的设计包含各种改变,并且在必要的 时候也应该接受任何风险。我想要澄清,好的设计具有创造性,但是创造性并不是促成好设计的唯一元素。

当你将这点运用于Magic游戏中,同样的说法也是,游戏设计必须始向前走。每款新的设计都必须好好衡量它的纸牌,机制,以及不同情境下的主题是否曾经出现过,而现在又有 何变化。是否现代技术能够让我们利用一些新的优势而创作出不一样的产品?如果可以,我们又应该如何做才能够在不改变游戏本质的基础上做出适当的变化?

computer vs tablet design(from wizards)

我认为每一款游戏设置都需要采取一些方法而达到创新:

1.每一个新设置都需要尝试一些之前从未尝试过的改变。虽然不一定是新的关键机制的改变,但是通常情况下这也是不可避免的。

2.每一个新设置都应该以一种全新的理念去改变过去或者现在的元素。有时候这种改变意味着进一步的发展,但是有时候也未必。

3.每一个新设置都应该想办法在旧理念的基础上添加一些新元素。换句话说,也就是每个新设置都应该让你能够在桥牌基础上添加新的卡片。

4.每一个新设置都应该让玩家能够转变对游戏的看法。

5.每一个新设置都应该能够创造一种属于自己的独特契机。这里所说的契机是指我在游戏设计中总是在寻找一个独特的瞬间,让我能够真正感觉到“就是这时候了”。《Zendikar 》是第一款让我想要创造一片领土而不再是一堆法术的游戏。我总是让自己处身于一个完全相反的情境下,并在这种倒置的氛围里我才能够更好地意识到一个设置的真正魅力。

我想如果哪一款设置能够真正执行这5种方法,那么它一定能够带来不一样的创新。

2)好设计具有实用性。

经常地,当我在速食店的厕所里,我总是会选择使用烘干机而不是卷纸巾,很多拥有同样习惯的人会回答:这样更环保,不会浪费纸资源,并且更加卫生。但是对于我来说,只是 因为“它能帮助我烘干手。”

在设计中也是相同道理,任何产品都必须具有自己的功能。如果一款设计不能够让用户有效安心地进行使用,那么这必是一款失败的产品。这里我所强调的便是,任何设计都必须 围绕着产品而运转,不应该脱离产品的本质属性。

iPhone(from wizards)

如何将这一点运用于游戏设计中?首先必须明确游戏的功能是什么。答案多种多样,而我也始终坚持于我所认可的答案:游戏的功能便是为人们创造乐趣。是的,游戏还应该刺激 思维,促进交流,测试玩家等等,但是总归,如果游戏不能够提供给玩家乐趣,那这一切功能又有何意义?

我经常询问我的Magic游戏设计者,为何特别的纸牌或者机制或者设置能够让玩家感到有趣。如果他们说不出其中的乐趣,我便会让他们去“寻找乐趣的源点”或者放弃这些设计。 通常,如果连设计者都搞不清楚自己制作每一张纸牌的首要目标是什么,那么他们便很容易陷入无止尽的迷茫和困惑中。

我经常提及我在《奥德赛》(游戏邦注:古希腊史诗)中学到的一些内容。在设计中,我利用了纸牌的优势,让玩家不用手便能够控制这些卡片。但是问题就在于,离开了手的控 制,纸牌游戏也就不那么有趣了。但是至少玩家想要玩纸牌。所以如果我能够让他们清楚自己为何要这么做,那么不管任何游戏方法,都能够让他们开心地玩游戏了。而如果我不 能让玩家想要尝试游戏,那么我就是个失败的设计者。

3)好设计具有美感。

美学是我经常谈及的另外一个话题,也是设计中非常重要的一部分。简要概括所谓的美学:如果一件问题让我们“感觉不错”,我们便会在意它。有些特性会造就舒适,也有一些 会引起不适。

美学的作用是帮助一件物品博得人们正面的回应。美学是一门学科,能够更加客观地为我们判别一件物品的好坏,而不只是凭借我们独断的猜测。从生物学的角度来看,人类总是 在渴求一些事物,如平衡性,结构性和完整性等等。而对于设计者来说,他们更加需要理解美学,因为这将深刻地影响着他们的设计会得到怎样的反馈。

对于任何一种艺术来说,很重要的一部分便是学习艺术规则。就像画家必须了解透视图,摄影师必须掌握光线,作家必须知道如何构造故事。而等等的这些规则都是来源于美学。 也就是图画,照片或者故事等都必须让观众能够有种“感觉不错”的反应。

游戏设计也不例外。游戏也必须让玩家“感觉不错”。特别是对于Magic游戏,我们必须了解那些表面上看起来不重要的许多因素。包括我们需要使用多少特殊机制以及我们是如何 为其上色和布置。其中也包含我们设置了什么能力等。当设计者在纸牌上添加或者删减了某些元素后,他们必须知道这些纸牌能够带给玩家何种感觉。

iPhone (from wizards)

美学同时也帮助我们更加谨慎地处理那些即将用于纸牌中的不同元素。最典型的例子便是我们如何使用数字。我们都很清楚什么数字会出现在纸牌上,以及什么时候这些数字间会 产生关联性。举个例子来说,如果一个生物在进入战场时拥有3个破坏点,我们将会让这个生物拥有3个级别的能力,因为我们希望这个生物在进行游戏时具有“攻击性”。

通常情况下,如果纸牌上的一些数字相互匹配,我们也会想办法让其它数字也搭配起来。几周前,我解释了我们是如何谨慎处理平等派中的能量/强度的结合,从而让游戏的进程更 加自然。虽然这些内容看起来都不起眼,但是当它们适当地结合在一起之时,便能够让整体的游戏设置看起来更加合理,适当。

4)好设计有助于我们了解产品。

我最欣赏苹果产品设计的一点便是,它总是能够满足我们的任何一种期待。苹果设计者总是很重视用户的期待,以及他们的产品是否能够满足用户的这种期待。这种观念对于设计 来说很重要,我将其称之为“回形针效应”。当你第一次看到回形针时,你会很自然地想到这就是一种用来别住多张纸的工具。这便是一目了然的设计原则。同时也包含了它的目 的,也就是它的使用方法。即让使用者能够清晰地知晓它的作用。

Rams同样也提到了,对于设计来说,用法说明也是非常重要的一大因素。在设计一件物品的同时你也应该向用户解释它的使用方法。我们很容易会把设计误解成是一种简单的装饰 ,只是尝试着创造一种外观好看的物品。所以在此,Rams是在提醒设计者,他们在传达外观的同时也必须传达相关信息。

这点在Magic游戏中特别重要,因为在交易类纸牌游戏中便带有很多局限性。设计者并未掌控玩家在游戏中的顺序。这就意味着他们必须谨慎地处理游戏中的任何进程。而最好的方 法便是使用一些普遍卡片。这些卡片可谓是游戏设置的主干线,因为它们的数量很多。如果设计者想要传达游戏设置的相关信息,那么他们就必须确保这些信息的清晰明了。就像 我常说的,如果你的主题不够明显,那么那就不是你的主题。

good design(from wizards)

好的Magic游戏设计必须能够传达信息。通常通过2个方法进行传达。首先是纸牌与纸牌间的信息传达。每张纸牌上都有许多地方可以用于提供各种信息,包括规则文本,纸牌的型 线,能量/强度,标题,艺术,趣味文本等。设计者还必须清楚什么时候应该使用哪一部分内容等。

以下我将列出一些用于传递设置信息的道具:特殊的物品,颜色,周期,反响等。传达游戏设置的一部分内容是设置平行纸牌从而强化你的游戏主题。你需要记住,玩家共有5次机 会能够找到传统的5色周期,而不只是单一的纸牌。

设计者不应该只是了解产品本身,而应该能够描写或解释他的设计。当用户首次接触你的产品时,也就只有你的产品能够帮助你传递所有的信息了。

5)好设计不会很高调。

当我来到好莱坞的第一年,我只能作为一名勤杂工,说得好听点就是产品助理。而这个角色正是位于好莱坞“食物链”的最底层。你必须执行任何上级所指派的任务。

在Lee Curtis和Richard Lewis主演的电影《Anything but Love》中,我的工作就是产品助理。某一天我被叫到一个制作人的办公室。这个制作人的工作便是监督我们这些助理。 他让我进入办公室并坐下,然后跟我说最近有一些人对我抱怨连连。我便很惊诧,难道我做得不够好?不可能,因为我自认为都很好地完成了任务。还是我没能完成某些任务?也 不对,因为我都按照要求执行了相应的任务了。还是我做了一些不该做的事?没有吧,我从来不会轻易逾越。那么我就纳闷了,我到底哪里做得不好?他随后说道,问题便在于, 我的行为太过于显眼。

太显眼?这是什么意思?他解释道,作为一名助理,就必须尽可能低调地执行任务。他们不应该被注意到。而我则拥有太多主见,所以很容易被关注到。这种行为在别人眼中也许 太过碍眼了吧。

那时候我对此感到非常沮丧。因为我之所以选择从事低级别的助理,正是希望能够借此不断攀升。我希望得到别人的注意。直到许多年过后,我才明白这位制作人的意思。作为一 名有效能的助理,我的工作便是完成所有要求。而不应该奢望得到任何关注。我应该默默地完成我的所有工作。因为我的角色是促成所有大工作中的一小块零件,所以我应该无形 地存在于基层中。

unobtrusive(from wizards)

从我的角度来看,我选择这份工作的目的很明确,只是希望能够以此为跳板转移到其它工作中。但是在制作人眼中,情况就完全不一样了。他希望我能够按照他的要求完成一切任 务,但是我却做不到默默无闻。我想要尽一切可能地凸显自己,但是因此我便无法适应这个圈子。

让我们再次转到Magic游戏设计中。任何一张个体纸牌的角色便是满足游戏设置的需要。纸牌的首要职责是服务于设置,而非自己。对于设计者来说,最难的工作便是应对一张不轻 易服从的可怕纸牌。如果这张纸牌凸显于其它纸牌中,那么它便破坏了整体的游戏设置。设计者的工作其实就像是之前提到的制作人,他必须监督着游戏系统的整体运行。是的, 对于纸牌来说,设计者约束了它们的发挥,但是从设计角度来看,比起个体纸牌的需要,整体目的更加重要。

我认为Rams在此的观点是,所有因素都应该首先满足于设计的需要。如果任何一个因素凸显于设计之上,那么它将会严重破坏整体的设计感。这个观点不论是在制作灯具,播放器 还是在Magic纸牌中都同样适用。

6)好设计是诚信。

我曾经接受了很多关于创造性写作的课程,其中最让我印象深刻的是大学时候一位英语女教授的课。那堂课与我之前接触过的创造性写作课程不同,老师并不是喋喋不休地专注于 教授我们如何写作,而是更加倾向于让我们学会观察并理解别人的作品。也就是,比起制作红酒,她更喜欢品酒。她是创造性小说的鉴赏家。这对于创造性写作老师来说是一大优 势,因为这让她能够从其他老师所抓不到的视角去看待这门课程。

我记得某一天,她问了全班一个问题:对于一名作家来说最重要的职责是什么?她的答案是–诚实。我们问道,对什么诚实?对任何事物诚实–对作为作家的自己,对你的角色, 对你的故事以及对你的读者。她认为,写作最重要的任务是让读者能够找到故事中蕴含的真理。这意味着什么?她说写作的核心是观察和交流。作为作者,我们总是在寻找关于人 类境况的各种真理,而一旦你找到了它们,你就必须刨根究底地去挖掘本质,并与你的读者进行分享。

另外一种思考方法便是,从另一个角度去看待这个问题,即从读者的视角进行思考。想想你曾经看过的书中讲了什么。是什么让你喜欢一本书?作者总会找机会与读者沟通,并传 达书本中的核心内容。作者们只是用语言表达出我们平时欲言又止的一些内容罢。作者与你,也就是读者,建立起某种联系,或情感,或精神,或逻辑关系。他们会用常人不擅长 的方法进行表达。

righteousness from wizards.com

如果作者的最终角色是创造出深层次的联系,那么他们就更需要诚实地表达自己所想要传达的内容。如果他们想要挖掘真理,那么他们就需要坦诚地去寻找这些真理。但是为何诚 实以对如此困难呢?因为,人们已经习惯了对自己撒谎。生活中总是充满各种不如意,我们总是难以应付一些所谓的事实。就是因为这样,人类才会习惯于避开那些让人痛苦的事 。但是,作者,却是个不能够选择逃避的角色。他们必须迎面任何好与坏,虽然这不是件易事。

但是我们说了这么多,又与设计有何关联?当然了,关联可大了。我相信,作者并不是唯一一个站在追求真理浪尖上的角色。我相信,所有艺术家都在努力面对着相同的问题。而 在我眼中,设计者就是艺术家。

游戏设计者也面临着与作家相似的任务,即创造出一款能够与观众相联系的游戏。我们也总是在努力寻找真理。而我们心目中的真理却与作家们所寻找的不相同。为什么?因为我 们是基于不同媒介而进行创作。写作是关于文字与交流;而游戏是关于行动与决策。游戏设计者通过让玩家遭遇与现实生活不同但相关的境况而传达基本的游戏真理。

举个例子来说,游戏可以通过逆境体现真理。众所周知,在生活中我们总是面对着许多难以决定的事。而这些困难的决定还常常把我们圈在一个没有任何人的牢笼里,只剩下我们 自己。遭遇逆境的感受,应对挑战的情感以及当你身边发生了不好的事而你又必须做出决定时的内心想法等人类的普遍情感。而游戏则为你创造了一个安全的环境,就像书籍给予 你的寄托,你可以避免面对现实世界中的那些害怕与恐惧。游戏与书籍一样,都是用来帮助我们发泄情感的好工具。

如何将此运用至Magic设计中?设计者总是愿意以宏观(障碍物设计)到微观(纸牌设计)的角度检验自己的工作,做出相关决策。一方面你需要听从你的直觉,一方面你必须确保 你的想法是否适用于游戏机制,以及你的小规划是否能够匹配规划等等,而这又与神话故事有种异曲同工之处。

诚实才能确保你不会让自己的喜好控制视角,你所创造的纸牌不应该是根据你能够做些什么,而是你需要做些什么。纸牌不管在虚拟空间,还是在实际联系中,都应该有真实感。 你应该按照观众的要求进行实践。总之,作为一名诚实的Magic设计者,你必须尽可能地让你的纸牌得到玩家的信任。

7)好设计经久耐用。

当我还是婴儿的时候,我曾经收到过一条柔软蓬松的明黄色婴儿毯。在我早期的记忆中,那是一条我在睡觉时盖着的柔软的黄色毛毯。小时候,我到哪里都离不开这条毯子。但是 后来,我的父母告诉我,这条毯子太过残破了,我最好不要再把它带出门,而我想说洗一洗应该就没事。但是又过了一段时间,我的父母再次跟我强调,这条毯子真的不应该再跟 着我出门,我就在晚上睡觉时盖就好。但是这样它白天不就“无事可做”了?我记得,在我7岁的时候,这条毯子最终消失匿迹。

在我14岁的时候,某一天我和妈妈一起坐在缆车上(小时候我们的家庭度假大多选择滑雪),她随口提到以前和我爸爸一起“剪碎”我的婴儿毯子的事。什么?!她继续阐述着这 个故事,在我7岁的时候,她和我爸爸曾经联系过我的儿科医师,因为他们都认为我已超过使用婴儿毯子的年龄。医生也同意了他们的观点,并给出了以下建议:每晚,当我睡着之 后我的爸爸妈妈要偷偷溜进我的房间,并拿剪刀在婴儿毯子的边缘剪出一条缝。这样随着时间的推移,毯子将会越来越破。而当毯子变得越加破烂时,他们就有理由劝我不要再使 用它,把它留在记忆中。

darksteel from wizards.com

显然,对于一个7岁的儿童来说,他没有能力去辨别为何自己心爱的毯子会越来越破,或者至少他不懂这种破损并不符合常理,直到在缆车听到真相。那时的我真的很失落。我关于 这条毯子的记忆真的很美好,但是最后却知道它是如此下场,我真的很难过。后来我花了一段时间一直在思考一个问题,即为何这件事会让我如此伤心?我的答案是,因为我失去 了最心爱的童年玩意儿。

许多年过后,当我再次回想起这个事件时,我问了自己一个问题:为什么我称那条毯子是我最心爱的童年玩意儿?因为我所有的童年记忆都与之相关。那为何我有如此多与之相关 的记忆呢?为何它能够击败我的其它玩具或者其它婴儿毯而成为我最喜欢的童年回忆?最简单的原因便是,它的寿命比其它东西都长。我之所以会有这么多关于这条毯子的记忆, 是因为它总是待在我身边。所以我最心爱的毯子的最重要特征是–经久耐用。

如果你想要创造一样经得住时间考验的产品,那你就必须确保这件产品有能力与时间相抗衡。我经常提到我们是如何看待Magic游戏。就像研发部门所考虑到的,我们并不想制作一 款转瞬即逝的游戏,而是希望我们的游戏能够长久地存在着。这就等于我在设计纸牌中所说的长久性。我的目标并不是创造能够满足当前需要的纸牌,我想要创造出经典。这种动 力非常重要,因为它能够帮助你的设计更上一层楼。一次性的物品有一次性的设计理念。而经典的东西也应该采取永恒的设计理念。

你的设计心态非常重要,如果你激起了这种斗志,那么设计也就只是一种心理活动而已。如果你解决问题的方法只是寻找答案,这样你将会在偶然找到一个答案后便失去任何兴趣 。当你的设计再上一层楼后,你可以重新回顾过去那些简单的答案,并从中寻找一些更加适当的方法,做出更加优秀的设计。作为一名Magic设计者,我认为如果我能够制作出一款 经得起挑战的游戏,并拥有许多效仿者,那么这也许就是我最引以为豪的一款游戏。我之所以会这么想是因为我知道我的工作有更高的目标,而不只是填充空白文件。当我在设计 的时候,我会努力寻找答案,而如果需要的话,我也会努力寻找更多需要解答的问题。

在制作出经典游戏的过程中,你必须不断测试你的设计。而最重要的测试工具是时间。如果你可以制作出任何超越你游戏设置的内容,并让它成为游戏的一大组成部分,那么它必 将能够成为你的宝贵财富。

8)好设计不放过任何一个细节。

当你真正从事写作多年时,你会发现比起自己内心的愿望,你的作品更加突出的是个人主题。我曾经遇到一位写作老师,她认为每一位作家都应该有属于自己的独特主题。如果你 研究各作家的作品,你会发现他们都有一个与别人不同的特殊主题内容。这是个思维训练,不断询问我们是否找到自己的主题。

在经过多方面思考,并反复阅读我自己的作品,我最终得出了结论,即我的个人主题是:当人们总是尝试着用各种原因和逻辑去束缚生活时,他们生活的核心也深深受制于情感。 我之所以会得出这个结论是受到我曾导过的一出独幕剧的影响,在这出剧中,主角通过在董事会中进行情感斗争而解决了一场道德困境。(这部剧叫做《Leggo My Ego》)

我又是如何在游戏研发中实践这一个人主题?我创造了玩家的心理统计特征,并以此解释不同内容是如何在情感方面满足不同玩家的需求。作为游戏设计者,我们可以尝试着从逻 辑上推断玩家需要什么,但是最终,我们还是要真正了解他们的情感,才能传达最优秀的游戏体验。

gutteral from wizards.com

但是这些又与原则8有何关系?就像我说过的,关系可大了。理解情感的一方面也要求我们要知道你能给予对方何种动力。这个问题的答案很多,其中一个答案便是–关注点点滴滴 的小事。比起面对大局,人们更喜欢处理一些小细节。如此,他们会在面对一些小事物时投入更多情感因素。也就是,如果一位艺术家能够设法完成一件件细微的小任务,那么这 就标志着他们最终定能够圆满完成更多大任务。

关于这点的最好例子是,你可以回想一下你最喜欢的电视节目,想想你是从什么时候开始真正喜欢它。我最喜欢的电视节目是“捉鬼者巴菲”(游戏邦注:这是一部风靡美国的电 视影集)。在第一季中,巴菲必须与一位女巫进行抗衡,这位女巫尝试着通过“太阳谷高中”而走向魔界。在这一季中,巴菲成为了啦啦队队长,但是这在当时并未起到特殊的作 用。(根据记录,第一季在整个系列中收视率最低)而这一季以女巫被困在啦啦队的奖杯中为结尾。我们也在最后看到了奖杯的特写镜头,一双眼睛缓缓睁开,我们知道,女巫已 被困在里头。

为未来铺设脚本。其中有一个场景是,一位名叫Oz的角色(扮演者是Seth Green)在“太阳谷高中”等待着巴菲。他一直紧盯着奖杯。而当巴菲出现时,Oz告诉巴菲这个奖杯一直 在环视四周。看起来这像是一句毫无关联的对白,但是这却真正在提醒广大观众,这就是这出剧的细节所在。而这些貌似不相干的细节场景却真的让我感受到了这个电视节目的优 秀所在。

这就是为何我总是努力创造类似“奖杯之眼”的时刻。这就是为何我会花很多时间去专研任何小细节的原因。大家会不断挖掘Magic设计。我希望自己的脚步更快。因为人们看重任 何小细节,所以这些小事物才会变得更加重要。

9)好设计重视与环境相协调。

我认为这点是10大原则中最容易被误解的一点。乍看之下很多人会以为Rams说的保护环境。但是我认为这却不是Rams的真正本意。Rams并未提及“自然、树木”环境,而是指游戏 道具的使用环境。如果一名工业设计师正在制作一展台灯,那么他就必须思考这展台灯能够被放在哪里。而且不只是位置,他也要思考谁会怎样使用这盏灯。所以Rams这里所说的 环境是告诉设计者应该把握所设计道具在用户生活中的合适位置。

在Magic设计中,这意味着许多不同的东西。当我们在设计一张纸牌时,设计者必须考虑玩家会将纸牌用于哪里。我们的每一块布景设置都设有一名主要设计者,而他的任务则是从 全局角度查看每块布景设置的合理性。所以,设计一块布景就像烹饪一道佳肴。一名厨师制作的不是各种食物,他也在通过各种食物创造一顿美味。厨师需将所有食材联系起来。 甚至是那些世界级大厨,他们会在正式餐宴前尝试制作不同样式,以此进行搭配,从而做出最令人满意的一桌宴席。

harmonize from wizards.com

而客人品味菜肴就等于游戏测试。事实上,设计技巧最重要的一点便是从游戏测试中吸取教训。就像经验丰富的大厨只要一根小汤匙就能够确定用量一样,游戏设计者也必须能够 通过玩纸牌而做出判断。只有这样,设计者才知道如何做出改变。完成某主题的设定还需要添加什么内容或者要明确一个固定方向应该适当缩减哪些要素?

“任何人都不是与世隔绝的孤岛。”这只是一张Magic纸牌。好吧,我猜想一座孤岛是一张Magic纸牌,但是如果你是想深入了解更多哲学观点而不只是表面内容,那么我的看法也 没有任何帮助了。设计者必须掌握每一张纸牌所处的情境。而如果设计者忽略了这一点,将会导致所有的场景设置出现相互矛盾的局面。

10)好设计就是尽量避免“设计”。

我是用多强的意志力才让自己不只是用草草的一段话概括了这一点并结束整篇文章。(对于那些新加入的读者来说,我也许是一个拥有很强观念的人。)就像我在原则8里提到的, 我们现在正处在设计领域,而我也就此讨论了很多。如果你的游戏不再依赖于某个组件,那么这个组件也可以脱离游戏了。任何东西都可以从你的设计中脱离出去。

为什么会这样?这与我在原则6中提到的类似。艺术的核心就是交流。而你作为一名艺术家,总是需要与观众进行互动。而如果你传达的信息越复杂,那么你就越难将其传达给观众 。而纸牌设计也是同样道理。如果我希望你关注纸牌的特定方面,那么每一个新添加的元素都会逐渐模糊我所要传达的信息。

第二个原因,也是很重要的一大因素是,根据定义,交易纸牌游戏是各种因素的混合体。游戏的核心是,玩家需要从上千种选择中挑出自己所心仪的桥牌。这就意味着至少会有60 张不同的纸牌混合在一起。为了使游戏看起来更讲究,你就必须尽可能地让每一张纸牌的表达更清晰,因为你很难回避混合纸牌时所出现的复杂现象。

barren Glory from wizards.com

第三,设计过程中总是需要意识到资源问题。设计空间看似很广,其实非常有限。如果一张纸牌就能够帮助你完成所有使命,那么你就要好好利用它去凸显其它纸牌。对于众多设 计新手来说,他们常犯的错误是不相信一个元素就能够完成一个优秀的纸牌设计。所以很多新设计者总是尽可能地往纸牌里塞进各种能够想到的内容。但是这样不仅会造成资源浪 费,而且会导致被塞得慢慢的纸牌不再有机会凸显魅力。所以我们必须牢记,特别是在纸牌设计中:如果有哪些元素即使去掉了也不会对纸牌造成影响,那么就果断撤销这些元素 !

根据以上分析,另外一个设计者常犯的错误是,总是执着于设计技术。比起创造所需要的设计,设计者好像一直在创造一些他们能够创造的内容。他们制作纸牌,仅是因为他们能 够制作这些纸牌,即使从整体看来这些纸牌没有多大作用。我想Rams正是看到设计中存在如此多不必要的修饰才会提出这一原则。好的设计必须是包含我们所需要的内容,同时排 除那些不必要的修饰。

Rams观点

我之所以将所有描述汇集在一起是因为我真的很欣赏这10大原则。就像我反复强调的,设计收音机闹钟与设计Magic设置没有多大差别。而这个想法也在我了解了Rams关于设计理念 的原则后进一步加深了。而且无一例外,这10大原则对于Magic设计都很重要。如果一名设计灯具的设计师能够帮助我这个Magic设计者,那么这就证明了我所说的设计具有普遍性 观点。

相关拓展阅读:篇目1,篇目2(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

I often talk about Brian Tinsman’s love of innovation. This doesn’t apply to just his Magic design, but to pretty much everything he gets his hands on. One day Brian was thinking about all the design resources of Wizards of the Coast R&D. Remember, that Magic is but one thing we create here (Dungeons & Dragons and Duel Masters the two big other roducts, but there are numerous smaller games created here as well). Was there a way to better synergize all this design talent?

The end result was the bi-weekly meeting of a group Brian called the Game Design Best Practice Team. Every designer in R&D was invited. Each time, a different designer would choose any design-related topic and use the hour meeting to talk about it. Today’s column was the topic I chose when I ran my first meeting.

Brain and Braun

My hour was all about the 10 Principles for Good Design as proposed by a man named Dieter Rams. I’ll start with where I started that day: who in the world is Dieter Rams?According to Wikipedia:

Dieter Rams (born May 20, 1932 in Wiesbaden, Hesse) is a German industrial designer closely associated with the consumer products company Braun and the Functionalist school of industrial design.

What does a man who designed consumer electronics have to do with game design? As you will see, a lot more than one might think. To understand the connection between Dieter Rams and myself, let me show you the key connection:

Who is this? This is a man named Jonathan Ive. He too designs consumer electronics products, although for a company that many of you might be more familiar with than Braun—a little company called Apple.

Jonathan Ive is the Senior Vice President of Industrial Design at Apple. More impressive to me than his qualifications, though, are his designs. Perhaps you ’re familiar with some of them:

What does Jonathan Ive have to do with Dieter Rams? Let’s take a look at some of Dieter Rams’s work:

Many believe that Dieter Rams is the industrial designer that has had the greatest influence on Jonathan Ive’s work. I believe Jonathan Ive to be one of the greatest modern industrial designers, so following this path of influence is of great interest to me. (If you’re unfamiliar with my love of Apple, check out my article where I professed it. By the way, for those who care: I did get an iPad the day it came out, and I’m loving it. It is very much, I believe, the direction of the future.)

Wait, wait, wait. I’m a card designer. What does that have to do with industrial design? My answer is “a lot,” because I believe that design is design regardless of what is being created. To be a better designer, I have to understand not just Magic design or card design, but the concept of design in general.

Today’s column (and the one in two weeks—it’s a two-parter) is looking at Dieter Rams’s 10 Principles for Good Design and talking about how the ten principles apply to game design and Magic design in specific. If you are truly interested in design, I think today’s column is an important one.

Let me start by showing you the list:

Dieter Rams’s Ten Principles for Good Design

1) Good design is innovative.

2) Good design makes a product useful.

3) Good design is aesthetic.

4) Good design helps us to understand a product.

5) Good design is unobtrusive.

6) Good design is honest.

7) Good design is durable.

8) Good design is consequent to the last detail.

9) Good design is concerned with the environment.

10) Good design is as little design as possible.

Take a moment to sink it all in. These ten principles carry a lot of weight. When you’re ready I’ll walk through them one by one.

1) Good design is innovative.

It’s hard to discuss this point without first discussing innovation. What exactly makes something innovative?

1.It has to be new, or at least new to the field in question. When you innovate in design, you bring a new element or elements to the table.

2.It has to bring about positive change. It’s not enough for something to just be new. The new thing has to change the design process in a way that moves the design forward.

3.It has to add value. That is, the change has to add something to the design that did not exist prior to its introduction.

4.It often has a negative or destructive effect. Most often when something is added, something else is taken away.

5.It tends to add risk. Change always comes at a cost.

The point I think Rams was trying to make here is that design is about moving forward. At each step you have to be willing to challenge what you know and examine potential ways to improve the design. Good design involves embracing change, when necessary, and being willing to accept risk. I will make the important distinction that good design is innovation, but innovation isn’t enough for good design.

When you apply this to Magic, what it is saying is that Magic design must keep moving forward. Each new design has to think about its cards and mechanics and themes in the context of not just what came before, but what can be done now. Does modern design technology allow us to approach things from a new vantage point? If so, how can we make changes that advance the game without pulling it away from the core of its essence?

I believe every Magic set needs to innovate in several ways:

1.Every new set should do something that hasn’t been done before. This doesn’t necessarily have to be as big as a new keyword mechanic, but more often than not it will be.

2.Every new set should bring back something from the past and present it in a new light. Sometimes this will mean further evolving it, but not always.

3.Every new set should find ways to add new elements to old ideas. Another way to think of this is that every new set should give you new cards to add to your old decks.

4.Every set should make players have to shift their thinking about the game in some way.

5.Every set should create a moment that is uniquely its own. What I mean by this is that in design I’m always on the lookout for the moment when you realize that this environment has its own feel. With Zendikar, it came the first time I found myself hoping to draw a land rather than a spell. I had been in the opposite situations a large number of times, and to see the situation reversed made me realize that the set was hitting on something cool.

I believe that if a set can accomplish these five tasks, it is bringing innovation to the design.

2) Good design makes a product useful.

Often when I’m at the bathroom of a fast food restaurant, I find myself forced to dry my hands with a hand dryer. It always has some sign that explains the many reasons it’s superior to a roll of paper towels: it’s better for the environment, it doesn’t create waste, it’s more hygienic. My response has always been, “If only it dried my hands!”

In design, form does, in fact, have to follow function. When design gets in the way of the consumer being able to use the product effectively, it is failing. This point stresses that design is supposed to work with the product and not against it.

To apply this to game design, you simply have to define what the function of a game is. While there are numerous answers, I’ll stick with my favorite: a game’s function is to be fun. Yes, it should stimulate the mind, it should enable socialization, it should test the player—it should do all sorts of things, but in the end, if the players aren’t enjoying themselves, nothing else maters.

I often ask my Magic designers to explain to me why a particular card or mechanic or set will be fun for the players. If they can’t explain to me what is fun about it, I tell them to “find the fun” or scrap it. Too often a designer can get lost in the intricacies of making a card work that they lose sight of why they’re making the card in the first place.

I often talk about the lesson I learned from Odyssey. In the design, I turned the concept of card advantage on its ear making it the correct play much of the time to throw away your hand to activate an ability you didn’t even care about. The problem is that throwing away your hand isn’t fun. Players want to play their cards. It didn’t matter if I could make them understand strategically why they might want to do it. If I can’t get them to want to do it, I, as a designer, have failed.

3) Good design is aesthetic.

Aethetics is another topic I touch upon from time to time as it’s such an important part of design. For a quick refresher, click this link to my a Zen and the Art of Cycle Maintenance. In it, I explain the basics of aesthetics. The short version for those who don’t want to hit the link is this: When perceiving things, humans care a great amount about if the object in question “feels right.” Certain qualities create comfort, while others create discomfort.

The role of aesthetics is understanding what generates a positive response from people. The science of aesthetics has told us that these qualities are much more objective than one might assume. Biologically, humans are wired to crave certain things: balance, structure, completion, etc. Designers have to understand aesthetics because it has a huge impact on how their designs are received and perceived.

A big part of any art is learning the rules of that art. Painters have to understand perspective, photographers have to understand light, writers have to understand story structure. Most of these rules come from the lessons of aesthetics. What does a painting or a photograph or a story have to do to “feel right” to the audience?

Game design is no different. Games have to “feel right.” For Magic, this means that we have to be conscious of many factors that might not seem important on the surface. This includes things like being careful how much we use a articular mechanic and where we put it in color and rarity. It also includes what abilities we put together. Designers have to be very conscious about the overall feel of a card as they add or subtract elements.

Aesthetics also makes us very careful about how we use different elements on a card. The best example of this would be our use of numbers. We are very aware what numbers appear on a card and when those numbers feel as if they want to have relevance to one another. For example, if a creature deals 3 damage when it enters the battlefield, we strongly push towards making the creature have a power of 3, as we want to create the feel that the creature is “attacking” as it enters play.

Often when several numbers on the card match we push to line up other numbers as well. Several weeks ago, I explained how we were very careful about what power/toughness combinations we used on the levelers to make their progression feel right. All of these things might seem small in a vacuum but the combined effect of caring about all these small things is that the sets have the right feel.

4) Good design helps us to understand a product.

One of the things I love about Apple’s design is that things tend to work the way you think they would work. The designers at Apple take great care to match expectation. This concept is so important to design that I’ve nicknamed it; I call it the Paperclip Effect. The first time you are shown a paper clip, it feels natural. So natural, in fact, that it becomes hard to imagine any other way to temporarily hold multiple pieces of paper together. That’s the sign of clean design. It so encompasses its purpose that it eclipses the idea that it is but one way to do it. It feels like the way, not a way.

Rams is also talking, I believe, about the importance of a design serving as instruction. The object needs to be designed such that its very form explains how it is used. It’s easy to think of design solely as cosmetic, to create the prettiest version of whatever it’s trying to be. With this principle, Rams is reminding the designer that they trade in information just as much as image.

This is especially important in Magic because of the limitations of trading card games. The designer does not control in what order the player experiences the game. This means that great care has to be taken to communicate what is going on. The biggest way this is accomplished is by use of common cards. These cards are the backbone of the set, because they will exist in the largest volume. If the designer wants to send a message about what the set is about, that message has to live in common to ensure that it will be seen. As I often say, if your theme isn’t in common, it isn’t your theme.

Good Magic design has to convey information. This is done in two ways. First is the card-by-card information. Each card has numerous places to provide information: the rules text, the card type line, the power/toughness, the title, the art, the flavor text, etc. The designer has to understand when each part can and should be used.

Next are the tools used to communicate information about the set: rarity, color, cycles, reflections, etc. Part of conveying things about your set is setting up parallel cards that reinforce your themes. Remember that a player has five times more chance to see a traditional five-color cycle than a single card.

A designer has to always be conscious not just of what the product is, but of what its design says as an introduction. When someone sees your product for the first time, it will be up to your product to convey your message.

5) Good design is unobtrusive.

During the first few years I was in Hollywood, I worked as a runner. (You can read all about my runner days in my column Tales of a Runner.) Also called a production assistant or a “go-fer” (as in”go fer” this and “go fer” that), a runner is the lowest person on the Hollywood food chain. You basically do whatever errands you are told to do.

One of my jobs was as a runner on the show Anything but Love starring Jamie Lee Curtis and Richard Lewis. One day I was called to the office of one of the producers. It was his job to oversee the runners. He called me in and told me to take a seat. He explained that there had been some complaints about me. Was I not doing my job efficiently? No, I was doing a good job. Was I failing to perform some task? No, I was doing everything asked of me. Had I done something I wasn’t supposed to do? No, I hadn’t stepped out of bounds. Then what was I doing wrong? The problem, he said, was that I was too visible.

Too visible? What did that mean? He explained that part of a runner’s job was to be as low-key as possible. A runner was not supposed to be noticed. I had too much personality. I was getting noticed. I wasn’t unobtrusive.

At the time I was pretty upset. The whole reason I took the low-level runner job was to work my way up. I was trying to get noticed. It wasn’t until many years later that I began to understand what he was saying. To be an effective runner, I had to fulfill all requirements of the job. An important one was that I wasn’t supposed to pull focus. I was supposed to do my job without causing any disruption. I was supposed to be invisible, because my job in the big picture was a supporting one.

It’s very easy to see the job from my perspective. I was using it to try and move on to something else. The harder part is to see it from the producer’s perspective. He had a need that had to be filled. I wasn’t giving him everything he needed. Instead of fitting into the organization, I was trying to stand out. It was problematic.

Let’s apply this to Magic design. The role of any individual card is to serve the needs of the set. The card’s first duty is to the set, not to itself. One of the hardest things for designers to do is to pull the awesome card that isn’t quite doing what it’s supposed to be doing. The problem is that the card is less important than the set. If the card pulls focus, it disrupts the set. A designer’s job, much like that producer, is to look at the system as a whole. Yes, it’s disruptive from that card’s perspective, but the design has a purpose much larger than an individual card’s need.

I think Rams’s major point here is that all the elements have to serve the design first and foremost and no other. The second any one element puts itself above the design as a whole, it jeopardizes the design. This is true in making lamps or record players, and it’s true in making Magic cards.

Two weeks ago, I talked about a new biweekly meeting that Brian Tinsman put together to allow all the designers of R&D to gather together and share ideas with one another. The idea is that at each meeting a different designer gives a presentation on any design-related topic he chooses. The presentations are a jumping off point for discussions most often leading back to the design we do on our games. For my first presentation I examined a document called “10

Principles for Good Design” by a German industrial designer named Dieter Rams. My contention was that design is design no matter if you’re making instants and creatures or lamps and clocks.

For each principle, I am talking about what I feel it means and how it affects Magic design. The first five principles were discussed in Part 1 and the second five will be discussed in today’s column. If you haven’t read Part 1, I strongly urge you to do so because I’m writing this column assuming you have. Let me refresh everyone’s memory by showing you the list:

Dieter Rams’s Ten Principles for Good Design

1) Good design is innovative.

2) Good design makes a product useful.

3) Good design is aesthetic.

4) Good design helps us to understand a product.

5) Good design is unobtrusive.

6) Good design is honest.

7) Good design is durable.

8)Good design is consequent to the last detail.

9) Good design is concerned with the environment.

10) Good design is as little design as possible.

I was so impressed with this list that I hung it up near my desk as a reminder of what I’m supposed to be thinking about. I’ll start today by just jumping in.

6) Good design is honest.

I’ve taken numerous creative writing courses in my life. My favorite was one I took in college taught by a female English professor. Unlike most of the creative writing courses I took, my teacher was not herself focused on writing, but on observing and understanding the writings of others. She wasn’t interested in making the wine; she wanted to taste it. She was a connoisseur of creative fiction. It was a unique vantage point for a creative writing teacher and it allowed her some insight that I never found in another class. (Yes, by the way, she was the one who had us write about the serial killer

having breakfast. Click here if you don’t know what I’m talking about.)

One day, she asked the class the following question: What is the most important responsibility for a writer? Her answer—to be honest. To be honest to what, we asked? To everything—to yourself as a writer, to your characters, to your story, to your audience. The most important task of writing, she felt, was finding the truth in the story you were telling. What exactly does that mean? She answered that the core of writing was about observation and communication. You, the writer, were searching for some truth about the human condition and once you found it you were digging down to its essence, then sharing that with your audience.

Another way to think about this is to approach it from the other side, as a reader. Think back to books that have spoken to you. What makes you love a book? Chances are the author managed to find something that you could really connect to, some basic idea that spoke to your core. The writer put into words something you were always feeling but never had the ability to express. The author made a connection with you, the reader, perhaps emotionally, spiritually, logically. They said something in a way that no one else was able to.

If the ultimate role of an author is to make that kind of deep connection, then it is fundamentally important that they approach the situation at hand as honestly as they can. If they are going to dig up truths, they have to be honest with themselves in the search for those truths. Why is this hard to do? Simply put, people lie to themselves all the time. Life is often awkward and uncomfortable. Certain facts are painful to deal with. As such, humans are pretty good at avoiding things that would be painful if actually confronted. Authors, though, don’t have the luxury of avoiding these things. They have to face them head on, and that is not easy to do.

What does any of this have to do with design? Everything, of course. I believe that authors do not stand alone in their quest for truth. I believe all artists struggle fundamentally with the same issue. As I feel designers are artists, perhaps you can see where I’m going.

A game designer has a similar task at hand. It is our job to create a game that seeks out the same type of connection with our audience. We too, are trying to find truths. The big difference is that our truths are a different kind of truth than an author looks to find. Why? Because we are working in different mediums. Writing is about words; it’s about ommunication. Games are about actions; they are about decisions. The way a game designer helps his audience

find a fundamental truth is by forcing him or her to encounter a situation that parallels something from their life.

I’ll give an example. One of the truths that games can connect on is adversity. One of the truisms of life is that there are hard decisions that have to be made. These decisions are difficult to make in the moment but shape us into who we are as individuals. The feeling of pulling through adversity, the emotions of stepping up to a challenge and finding what it takes inside of you to make the hard decisions when bad things are happening all around you is a universal feeling. Games allow you access to that feeling in a much safer environment, much as books can allow you to emotionally connect with feelings that would be much scarier to face in the real world. Games, much like books, have great potential for catharsis and identification.

How does this apply to Magic design? It says that designers have to be willing to examine what they do from the macro (block design) to the micro (card design) and make choices that come out of pursuing what the different element needs to be. Part of this is being willing to listen to your intuition about what feels right. Part of this is making sure that the flavor matches your mechanic. Part of this is making sure that your little picture matches your big picture, that common has the same message as mythic rare, that your creatures are communicating the same message as your instants.

Being honest means making sure that you aren’t letting your love of craft overstep your vision. Your cards shouldn’t be about what you can do but what you need to do. Cards need to ring true both in a vacuum and in conjunction with one another. Things need to do what your audience expects them to do. In short, being honest as a Magic designer means taking all the steps necessary to have your cards serve the vision.

7) Good design is durable.

When I was a baby, I was given the gift of a soft, fluffy bright yellow baby blanket. Eventually it became a soft, not so fluffy, dull yellow baby blanket. My earliest memory of it was as a soft brown blanket that I slept with. In my youth, I carried my blanket (named, by me of course, “Blanket”) everywhere I went. Eventually, my parents told me that Blanket was getting beaten up enough that it wasn’t a good idea to take it out of the house, as having to clean it would probably do significant damage to it. Some time later, my parents informed me that Blanket really should just stay in my room. I could sleep with it at night, but Blanket had to curtail most of its daytime activities. Then around age seven, Blanket, as I remember it, slowly vanished.

One day, when I was fourteen, while riding up a chairlift with my mother (most of my families vacations in my youth were ski vacations), she mentioned off- handedly about the time they “cut up my baby blanket”. What?! She went on to tell the story about how when I was seven, she and my dad contacted my pediatrician because they were worried that I was getting a little old for a baby blanket. The doctor agreed and made the following suggestion: each night over the course of several months, they come into my room when I was sleeping and cut a tiny bit around the edges of my baby blanket. This way the blanket would slowly shrink over time. When it got small enough, they could convince me to put it away in a memory book so it doesn’t get lost.

Apparently a seven-year-old doesn’t have the ability to notice that his beloved blanket is slowly shrinking or at least lacks the understanding that it isn ’t supposed to do that, so it worked. That is, until that fateful day on the chairlift. I was genuinely upset. I had very warm memories of Blanket and learning that it came to such a grizzly end was quite bothersome to me. As I spent time thinking about it, an important question came to me. Why did it bother me so much? Because, I answered, it was my most beloved childhood item.

Many years later looking back at this incident (the discovering of its removal more so than the removal itself), I am forced to ask myself the following question: what made it my most beloved childhood item? All the memories I had with it, of course. But why did I have so many memories of it? How did it beat out my rattle and my pacifier or one of my other myriad baby blankets? One simple reason—it just lasted longer than any of them. It had so many memories because it was around. The most important trait of my beloved Blanket—durability.

If you want to create something to last the test of time it has to, well, last the test of time. I often talk about how we think about Magic. As far as R&D is concerned, we’re not making a flash in the pan but a game we expect to outlive us all. What this means to design is that when I design a card I think long term. Am I making something that we could bring back the next time we revisit this theme? My goal isn’t just to make cards that play well in the present, I’m shooting for making something classic. This drive is important because it raises the bar on your design. Disposable things use disposable

ideas. Classic things use timeless ideas.

The mindset of your design is important because when you boil it all down, design is a mental activity. If you approach your problem merely looking for any answer, you will find the first one you stumble across then stop looking. When you raise the bar, you challenge yourself to look past the easy answers, to find the ones that allow what you are doing to transcend craft into art. As a Magic designer, I feel my best work will be able to stand up to the comparisons of those who follow in my footsteps. I feel that way because I know my work was aiming higher than filling holes in a file. When I design, I search for answers and, if need be, I’ll search for questions.

Along the way to making a classic game, you will have to put your design through many tests. The most important one though is the test of time. If you can make something that transcends your set to become part of your game, that is the ultimate legacy as a game designer

8) Good design is consequent to the last detail.

One of the things that happens when you write week in and week out for years is that you start to find not just your voice but your personal themes. I’ve talked about how I once had a writing teacher (different one) that claimed that every writer had a singular theme. That if you examined the entirety of any one author’s work you will find a singular theme connecting them. As a thought exercise, she asked us if we could recognize our own theme.

After much thought, and much rereading of my writing, I came to the conclusion that my personal theme is this: while people try to use reason and logic to govern their life, people are, at their core, run by their emotions. I figured this out while directing a one act play in which the main character solves an ethical dilemma by having his emotions fight it out in a board meeting. (The play was called Leggo My Ego for those of you that keep updating my wikipedia page.)

So, what happens when I show up at R&D? I create player psychographics to help explain what things emotionally satisfy each of our different types of players. (If you have no idea what I’m talking about, read this.) We as game designers can try to logically deduce what our players want, but in the end we have to understand their emotions to truly deliver the best experience.

What does all that have to do with this point? As I like to say—everything. Part of understanding emotions is understanding what makes them tick? While there are many answers to that question, one answer is this—it’s the little things. People have trouble focusing on the big picture, but they are great at observing the minutiae. As such, they put a lot of emotional weight on the little things clicking. The feeling is that if the artist manages to make all the little things work that it is symptomatic that the larger pieces are thought out as well.

The best example I can use to explain this is to think of your favorite television show. Think of a moment that really endeared you to it. I’ll give you one of mine for one of my favorite shows of all time, “Buffy, the Vampire Slayer.” In one of the early episodes of the first season, Buffy fought a witch that was trying to live out her former high school glory through her daughter. The episode involves Buffy having to become a cheerleader, but that’s not important right now. (For the record, this episode was below average for the series at large.) The show ended with the witch being trapped inside a cheerleading trophy. We see a close-up of the trophy’s face, the eyes open up and we get that she’s trapped there.

Flash forward to a few seasons later. There’s a scene in the high school where a character named Oz (played by Seth Green) is waiting for Buffy. As he does he’s looking at the trophy case. As Buffy approaches Oz, Oz makes a comment about how one of the trophies is looking around. Now, it’s a throw-away line. Its only purpose really was to remind the audience that Joss Whedon and his writers, like us, are fans of the show and that they remember the little things.

The moment, while irrelevant to that show, really stuck with me. It made me feel good about myself and good about the show.

That’s why I (and the rest of R&D) work hard to create those “trophy eyes” moments. It’s why we spend hours upon hours working on the tiniest of tiny details. Every facet of Magic is going to be explored by someone. When they do, I want to have already been there. Little things matter because to people, little things matter.

9) Good design is concerned with the environment.

I believe this point is, of the ten, the one most often misinterpreted. Most people at first blush think Rams is talking about being ecologically friendly. While it’s a nice thought (and yes, we should be where we can), it’s not, I believe, what Rams is talking about. (There is a chance I am completely wrong and if I am—go ecology!) Rams didn’t refer to the “nature and trees and stuff” environment but rather the environment in which the item being designed is to be used. If an industrial designer is making a lamp, he has to think about where that lamp is going to sit. Not just where, but how and by whom. What Rams is talking about here is—understanding where your design fits into the life of the person using it.

In Magic, this means numerous things. When designing a card, the designer has to be conscious of where the card will be played. Cards don’t live in a vacuum. They are part of numerous ecosystems. A designer has to think about that as they design. The reason we have a lead designer for each set is that it is crucial to have one person whose responsibility it is to look at all the cards in a set holistically. To use a metaphor (and I do love my metaphors), designing a set is much like cooking a meal. A cook isn’t just making various foods, he is making a meal using those various foods. Each has to be thought of in conjunction with the rest. If you watch world-class chefs, they do a lot of sampling of their food as they are constantly trying to monitor where the food is at so that they can make adjustments if needed.

Our food tastings are playtests and the method is not that far apart. In fact, one of the most important skills in design is the ability to learn from playtests. Just as a classic chef has to be able to gauge everything with a spoonful, so too does a designer has to be able to absorb as much as he can from playing with the cards. Only then, can a designer begin to understand what has to change. What needs to be added to round out a theme or subtracted to push focus back in a certain direction?

They say “no man is an island.” (That’s why whenever I would run Big Magic—Magic played at premiere events with giant cards each manipulated by a volunteer from the audience—I always picked a female to handle the islands.) Neither, I argue, is a Magic card. Well, okay I guess an Island is a Magic card, but if you go more philosophical and less literal, my point will stand. Each card lives in a context that the designer has to understand. Failure to do so will result in a set that doesn’t hold together.

10) Good design is as little design as possible.

Yes.

You have no idea how much willpower it took for me to not just make that last paragraph the entire comment on this point. (For those new readers joining us, I’m a high concept kind of guy.) Like Point #8, this is a design area that I talk about a lot. If your game can exist without a component, then that component shouldn’t be in the game. Anything that can be excised from your design should be.

Why? Why is that so? The reasoning dovetails back into something I talked about in point #6. At its core, art is about communication. You, the artist, are trying to connect with your audience. The more you clutter your message the harder it is to deliver it. The same holds true for card design. If I want you to focus on a particular aspect of a card, every addition just dilutes my message.

A second reason simplicity of concept is so important is that a trading card game is, by definition, a mixing of elements. At its very core, the player gets to pick and choose his deck from thousands of options. That means at minimum there are sixty different cards being forced to commingle. In order to keep the game elegant, you have to make all the pieces as clean as you can because you cannot avoid the complication that comes from the intermixing of the cards.Thirdly (I hope that’s a word), design has to always be conscious of resources. While there is a large amount of design space, it is finite. Designers do not have the luxury of wasting design resources. If a card can accomplish what it needs with just one piece it doesn’t need a second—save it to make some other card shine. One of the most common mistakes I see when looking at novice designs is an inability to trust that one aspect is enough to carry the card.

So many first designs are overstuffed with every thing the designer can think of. Not only are they wasting a valuable resource, they’ve so stuffed the card that no element has a chance to shine. Remember the truism above, even in card design: if something can be removed and the card will work, it needs to be removed.

Another common mistake made by designers under this point is something I talked about above. Be careful to not fall in love with the craft of the design. Instead of creating designs they need, designers create designs they can. They make cards solely because the cards are capable of being made, even if those designs have no role in the larger picture. It is this desire to add bells and whistles to designs that I think prompted Rams to include this last point. Good design has to look past what is possible for what is required.

Rams Tough

I put this presentation together because I am fascinated by design as an overall concept. As I’ve explained numerous times, I don’t see that much difference between designing a clock radio and designing a Magic set. This belief was only further entrenched as I starting looking through what Rams had to say about design. Without fail, every point is an important one to Magic design. If a man who designs lamps for a living can help make me a better Magic designer, then it helps prove my point that design is universal.

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号