万字长文,Ian Schreiber从多角度谈游戏制作系列1

什么是游戏?

我(作者Ian Schreiber)之前的定义是:涉及冲突的有规则体验活动。但“什么是游戏?”这个问题要复杂许多:

* 首先,这是我的定义。当然这也是IGDA Education SIG所采用的定义。

业内还有许多同我相左的定义。这些定义很多出自经验比我丰富之人。所以这个定义还有值得探讨的地方。

* 其次,这个定义并没有涉及如何设计游戏,所以我们将从游戏组成要素(规则、资源、行为和故事等)角度讨论什么是游戏。我把这些叫做游戏的“形式要素”。

Tic-Tac-Toe(from-free-extras.com)

区分不同游戏也非常重要。以《Three to Fifteen》为例,你们大多没有听过或玩过这款游戏。其规则非常简单:

* 玩家:2人

* 目标:收集3个相加等于15的数字

* 游戏设置:首先在纸上写下数字1-9,选择首先进行体验的玩家。

* 继续游戏:轮到玩家时,选择未被其他玩家选择的数字。你可以控制这个数字,将其从数字列表中去除,在纸张的侧面写下这个数字,以此说明这个数字现在为你所有。

* 解决方案:若有某玩家收集到3个相加等于15的数字,游戏便终止。此玩家便成为赢家。若9个数字都被收集后,没有玩家胜出,游戏便是平局。

大家不妨尝试这款游戏,或同自己较量,或同其他玩家角逐。

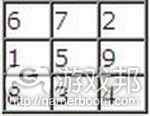

数字1-9可以3×3的网格模式呈现,也就众所周知的“纵横图”,其中每行、每列及每对角线的数字加起来都等于15:

grid(from-wordpress.com)

现在你就心中有数。这就是一字棋游戏。那么一字棋和《Three to Fifteen》是大同小异,还是存在差异?(游戏邦注:这取决于你的定义)。

评论词汇

我所谓的“词汇”是系列供我们讨论游戏的词语。“评论”在这里并不是指我们非常吹毛求疵,而是说我们能够批判性地分析游戏。

词汇也许并不像你所设计的激光机器忍者那般有趣,但这非常重要,因为这是我们谈论游戏的方式。否则我们就只能用手比划,用嘴嘟哝,若无法交流,我们将很难学习东西。

谈论游戏一个最常见的方式是用其他游戏形容它们。“这就像《侠盗猎车手》混合《模拟人生》和《魔兽世界》。”但这存在两大局限性,首先,若没有体验《魔兽世界》,我就 无法明白你的意思;这要求我得同时玩过这两款游戏。其次,更重要的是,这不适合游戏类型不同的情况。你如何基于其他游戏谈论《Katamari Damacy》?

另一常被创作游戏设计文本人士选择的方法是必要时候创造新术语,始终如一地应用于文本中。我可以这么做,这样我们至少能够互相沟通游戏设计的基本概念。这里的问题是课 程结束后会出现什么情况;本课程的术语就会变得毫无用处。我无法要求或命令行业采用我的术语。

有人也许会问既然通过某些词汇讨论游戏如此重要,那为何我们至今依然没有这么做?为何游戏行业没有设定系列术语?答案是他们目前正在进行,这是个缓慢过程。未来阅读资 料将出现许多这类词汇。

游戏和玩乐

玩乐的方式有许多种:传球,假扮,当然还有游戏。所以你可以把游戏当作一种玩乐方式。

二者怎么可能互为子集?这有些自相矛盾。在我们看来,这没有影响——这里的重点是游戏和玩乐是相互关联的概念。

那么什么是游戏?

你会发现我至今都还没有回答这个问题。这是因为这个概念很难定义,很难确保将所有游戏内容都囊括在内(游戏邦注:同时保证将非游戏内容排除在外)。

下面各种版本的定义:

* 游戏要有“目标和工具”:目标、结果和系列实现规则。(David Parlett)

* 游戏是包含玩家决策的活动,是在“有限环境”中寻找目标。(Clark C. Abt)

* 游戏包含六大属性:“自由”(体验具有选择性而非义务性),“单独”(事先设定于某空间和时间中),具有不确定的结果,“非创造性”(不会创造商品和财富),受规则 限制,“虚构”(游戏不是现实生活,而是共享的独立“现实”)。(Roger Callois)

* 游戏是“自愿付出完成不必要的障碍。”这是最受大家认可的定义。这个定义听起来有些不同,但包含很多先前定义的概念:自发性,存在目标和规则。“不必要障碍”说明规 则故意拖延效率——例如,若一字棋的目标是横向、纵向及对角方向收集3个符号,最简单的方式就是在首回合在同一行中写下3个符号,同时让对手无法接触到纸张。但你并没有 这么做,因为游戏有自己的规则,这些规则是游戏体验的来源。(Bernard Suits)

* 游戏有4个属性。它们是“封闭而形式的机制”;包含互动;包含冲突;提供安全性,至少相比其所代表的实际内容(例如,真正的美国足球与以美国足球为蓝本的游戏)。 (Chris Crawford)

* 游戏是“玩家进行系列决策,通过游戏符合合理管理资源,从而实现目标的艺术形式。”这个定义包含许多前面没有的内容:游戏属于艺术,涉及决策和资源管理,游戏有“符 号”。此外,也涉及有常见的目标概念。(Greg Costikyan)

* 游戏是“玩家参与规则定义的虚拟冲突,进而产生量化结果的机制”(这里的“量化”是指存在“输赢”概念)。这个定义来自Katie Salen和Eric Zimmerman创作的《Rules of Play》一书中。书中还罗列上述系列定义。

通过讨论这些定义,我们现在握有探讨游戏的出发点。上述许多元素在很多游戏中司空见惯:

* 游戏是种活动。

* 游戏具有规则。

* 游戏包含冲突。

* 游戏具有目标。

* 游戏包含决策。

* 游戏是虚构内容,它们非常安全,脱离正常生活。这有时也指玩家进入“魔法阵”或共享“有趣心态”。

* 游戏无法给玩家带来物质收获。

* 游戏就有自发性。若你处在枪口下,被迫参与所谓的游戏活动,有人会认为这对你来说便不再是游戏(试着想想:若你认同这点,那么有些玩家自发参与,而其他玩家被迫参与 的活动则既是游戏,又不是游戏,这取决于你所处的立场)。

* 游戏具有不确定的结果。

* 游戏是真实内容的再现或模拟,但其本身采用虚拟模式。

* 游戏缺乏效率。规则会融入限制玩家采用最便捷方式实现目标的障碍。

* 游戏包含机制。通常这是个封闭机制,这意味着资源和信息不会在游戏和外在世界间流动。

* 游戏是种艺术形式。

各定义的缺陷

上述哪个定义最准确?

没有任何一个定义完美无缺。若你企图自己定义游戏,其中也会存在不足。下面是些常产生定义问题的边缘情况:

* 益智游戏,如数字游戏《数独》、《魔术方块》或逻辑游戏。这些是否属于游戏?在Salen & Zimmerman看来,它们是游戏的一种,游戏包含系列正确答案。而Costikyan则认为 ,它们不属于游戏,虽然它们可以融入游戏中。

Sudoku(from-zuige.net)

* 角色扮演游戏,例如《龙与地下城》。游戏名称就包含“游戏”一词,但其通常不被视作游戏(因为游戏没有最终结果或解决方案,没有输赢)。

* 《Choose your own adventure》系列书籍。这些通常不被视作游戏;你在“阅读”书籍,而不是“体验”书籍。但这几乎满足所有游戏定义的标准。更令人迷惑的是,若在其中 某本书中添加某页包含数值的“人物统计表”,随机决定在某些页面中融入“技能检测”,将其称作“冒险模块”而非“Choose your own adventure”,我们发现这就变成游戏!

* 故事。游戏是否属于故事?一方面,多数游戏都呈线性发展,而游戏则更具动态。另一方面,多数游戏都蕴含某些故事或叙述内容;如今甚至还有投身数百万美元视频游戏项目 的专业故事作家。除此之外,玩家还可以讲述自己游戏体验的故事。记住故事和游戏概念具有紧密关联。

制作游戏

你会好奇这些内容如何帮助你制作游戏。这并非一蹴而就,但我们需要首先先来看看某些共享词汇,这样我们能够以有意义的方式谈论游戏。

首先是关于游戏。很多同学都表示他们很担心自己能否制作出游戏。他们觉得自己缺乏创造性和技能等要素。这完全是废话,现在你将从我们的系统中把握这些技能。

若你之前有制作过游戏,完全无需有这样的担心。现在就来制作游戏。拿出纸笔。这只要15分钟,整个过程将非常有趣。

我们要制作的是所谓的瞄准终点的棋盘游戏。你可能玩过很多这类游戏;游戏目标是将自己的符号代表从棋盘某处移到另一处。常见例子包括《Candyland》、《Chutes & Ladders 》和巴棋戏。这些是最简单的游戏类型。

首先,先画小路。可以是直线,也可以是曲线。然后延伸出不同分支。

其次,寻找主题或目标。玩家需要从路径一端走到另一端;为什么?因为你或朝某物靠近,或避开某物。玩家在游戏中是什么形象?什么是游戏目标?设计游戏时,一开始就弄清 游戏目标帮助很大,很多规则都将基于此进行设置。你要能够在几分钟里想出些内容。

第三,你需要设定玩家在各空格中移动的规则。玩家要如何移动?最简单的方式是在轮到自己的时候掷骰子,出现什么数字,就移动多少步(游邦注:这个大家可能非常熟悉)。 你还要决定游戏的结束方式:玩家是得掷出准确数字方能抵达终点,还是只要掷出的数字足以到达终点,就算获胜?

现在你已把握所有游戏要素,虽然这里还缺少某个常见要素:冲突。若能影响对手,或帮助他们,或伤害他们,游戏会更加有趣。想想玩家同对手的互动方式。当玩家与对手同处 一个空格时,会出现什么情况?是否存在某些空格能让你影响游戏,如让他们前进或后退?轮到玩家时,他们是否能够通过其他方式移动对手(如掷出某数)?应融入至少一个能 够让玩家修改对手身份的渠道。

现在你已成功制作出一款游戏,游戏虽算不上优秀,但至少功能齐全。而且只用几分钟完成,所用工具不过是纸和笔。

这个创造方式要归功于布伦达·布瑞斯韦特。

所获经验

若你未从此训练中收获什么,至少请记住一点:你可以在几分钟内制作出游戏。这无需编程技术,无需丰富创造性,大笔资金、资源或其他特殊材料。整个过程无需长达几个月, 而只是着眼于某个简单构思,此构思只需用几张纸便能在较短时间内容完成。

深入更新内容和快速建模后,很多人会没有勇气投身设计工作,架构自己的构思。他们担心这会耗费过长时间,或者不如预期的那么好。这个过程涉及通过制作和体验自己的游戏 ,去除薄弱构思,将它们进一步强化。内容投入运作的周期越短,我们试验的机会就越多,游戏的效果就更好。若你利用超过几分钟的时间制作游戏首个模型,显然耗时过久。

游戏设计

“设计”这个单词将会频繁出现在这篇文章中,但是很不幸的是,在各类型文章中,这个词的使用实在太过于泛滥,所以我想在此详细解释我所说的“设计”到底指什么。就像在 《Challenges》中,游戏设计便是单纯指代游戏规则和内容的创造。其中并不包含编程,艺术,动画,市场营销或者其它游戏制作所要求的任务。所有的这些任务集中在一起被称 为“游戏开发”,而游戏设计只是游戏开发中的一个部分。

各种类型的游戏设计

就像我们所提到的《Challenges》,它的游戏设计便体现了各种任务,包括系统设计,关卡设计,内容设计,用户界面设计,建造世界以及故事编写等。你可以花10周的时间去学 习这些任务的相关课程,但我们的这系列课程将不会囊括游戏设计中的所有范围。我们将会略提到用户界面,故事编写以及相关内容,但本课程的主要焦点还是系统设计(有时候 我们也称之为“核心系统设计”)。

系统设计是关于定义游戏的基本规则。游戏的每个部件分别是什么?你要如何控制它们?你在每一步过程中会采取何种措施?你的每次行动会有何结果并且这些结果将如何影响游 戏?总的来说,系统设计可以概况为三大创造:

设置的规则。游戏是如何开始?

游戏进程的规则。一旦游戏开始后,玩家能够做什么,并且他们的行动会产生何种结果?

结果的规则。是什么导致游戏的结束?如果游戏产生了结果(如胜利或失败),那么这一结果能够决定什么?

如果你玩过《Three-to-Fifteen》这款游戏,你将会发现游戏中的所有部分都包含了非常简单的规则。正是系统设计创造了这些规则,而我们将花一整个夏天的时间对其进行研究 。

游戏设计师的定义

你也许注意到了,游戏设计是一个非常广阔的领域。尽管是作为专业游戏设计师的我们,也很难解释我们所从事的工作对于家人和朋友有何影响。一部分原因可能是因为我们需要 接触的事物实在太多了。以下是我所接触到的用于形容游戏设计者的一些类比:

游戏设计师是艺术家。“艺术”这个词很难用于定义“游戏”,但是如果游戏算是一种艺术形式(游戏邦注:就像资深的游戏设计师Costikyan所定义的那样),那么游戏设计者也 就自然等同于艺术家了。

游戏设计师是建筑师。建筑师的工作并不是建造实质的建筑物,而是创造建筑蓝图。视频游戏设计者同样也是在创造“蓝图”,也就是我们所说的“设计文档”。桌面游戏设计者 同样也在创造蓝图,即游戏原型,并最终交由发行商进行大量生产。

游戏设计师是派对主持人。作为设计者,我们会邀请玩家进入我们所创造的游戏世界,并努力为他们营造一个美好的时刻。

游戏设计师是做研究的科学家。我将在后面提到,创造游戏的方式其实类似于创造科学观点。

游戏设计师是上帝。我们创造了世界,也创造了能够支配这个世界的物理定律。

游戏设计师是律师。我们创造了一系列规则,并引导多数人按照这一规则行事。

游戏设计师是教育者。在阅读了《Theory of Fun》之后,我们会发现娱乐和教育是紧密联系着的,游戏之所以有趣是因为其中蕴含了一些新的学习技巧。

如果游戏设计包含了这些所有内容,那么就高校课程来说,它应该属于哪一门学科呢?它可以被归类到教育学院,艺术学院,建筑学院,神学研究院,娱乐管理院,法学院,工程 学院,应用科学院等等。

但是否游戏设计师的定位就只有这些?或者什么都不是?这是一个值得讨论的话题,但是我认为,游戏设计者虽然拥有各个领域的多种因素,但是却仍然伫立在一个属于自己的领 域中。而且这也是一个非常广阔的领域。当游戏设计领域进一步发展,我们也许在将来的某一天能够看到,那些专攻于“游戏设计”的设计者们将被会被细分到更多更加专业的领 域,就像“科学”领域的学生也有自己的专攻学科(游戏邦注:如化学,生物,物理等)。

游戏设计的科学

如何进行游戏设计?方法众多。

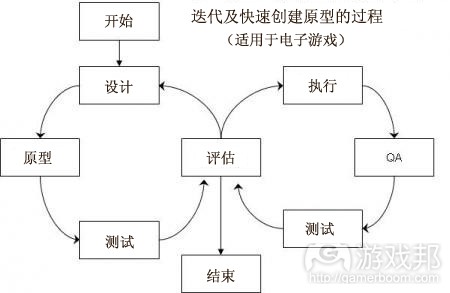

从历史上来看,第一种游戏设计方法也就是我们所说的“瀑布模式”:先在纸上设计出整款游戏的轮廓,随后去执行这个设计(游戏邦注:可使用电子游戏编程或者创造出非数据 游戏的模版和组建),然后测试它以确保所有规则的合理性,并添加一些图像让游戏整体看起来更加好看,最后发行游戏。

瀑布模式

瀑布模式(from gamedesignconcepts)

瀑布模式之所以如此命名是因为整个流程就像是倾泻而下的水流,你只能朝着一个方向前进。在这个模式下,如果你在最后几个步骤中遇到一些需要改变的规则,那么就糟糕了, 因为在这里,方法论规定你不能回到之前的设计步骤中。

有时候,有些人认为如果能够选择回到之前的步骤去修正一些内容是个不错的主意,而这也是我们后来所说的迭代式方法。而如果是瀑布模式,我们便只能沿着设计游戏,执行设 计,并确保设计可行这一直线路而行动了。但是你也可以在后来添加一个额外的步骤去评估你的游戏。玩游戏并判断它是否有趣或者哪里需要做出调整。随后做出决定:你是否完 成了任务,还是你应该回到之前的设计步骤进行一些完善?如果你认为游戏足够优秀了,那么你便完成了所有工作。但是如果你认为游戏尚待调整,那么你就需要回到之前的设计 步骤,找到问题所在,并针对性地进行修改,然后再次评估游戏。反复进行这一过程直到游戏真正得以完善。

迭代过程(from gamedesignconcepts)

如果你认为这种方法很耳熟,那是因为它其实等同于科学理论:

1.观察。(“我在玩游戏或者制作游戏中的体验都证实了一些游戏机制的趣味性。”)

2.假设。(“我认为我所编写的这系列特别规则将能够制作出一款有趣的游戏。”)

3.创造一个试验去证实或反驳这一假设。(“组织游戏测试并观察游戏是否具有趣味性。”)

4.执行试验。(“让我们玩游戏。”)

5.阐述试验结果,并组成一系列新观察。重新回到第一个步骤。

即使是非数字游戏(如卡片或者桌面游戏),这个过程也同样适用,因为它们能够更快速地得以实行。而即使是电子游戏在执行这一过程的时候也会出现一个问题:执行的成本( 如编程和试调)过高,并且很耗时。如果你只有2年的游戏开发时间,而单单编程就消耗了你18个月,那么你将没有多余的时间去进行游戏测试和完善。

但是一般来说,迭代次数越多,你最后成品的游戏也会越优秀。

因此,任何游戏的设计过程必须包含尽可能多的迭代过程(也就是必须包含设计,执行与评估这整个循环过程),而如果你能够越快执行这些过程,那么你将能够创造出更棒的游 戏。所以,电子游戏设计师经常会先在纸上画出游戏原型,并在他们肯定了游戏的核心原则之后交由编程员进行游戏编程。我们将这一过程称之为“快速原型”。

迭代和快速创建原型(from gamedesignconcepts)

迭代和风险

游戏总是避不开风险。包括设计风险,即游戏可能不够有趣,玩家不喜欢游戏;执行风险,尽管规则很明确,但是开发团队却没有能力完成所有的开发任务;市场风险,尽管游戏 很有趣,但是却没人愿意购买等等。

迭代的目的是降低设计风险。游戏的迭代次数越多,游戏规则的有效性便越有保障。

这些都可以归结成重要的一点:如果你的游戏存在越多设计风险(也就是你未曾测试或完善游戏规则),你就需要越频繁地进行迭代。但是如果一款游戏的机制是借鉴于其它成功 游戏,那么迭代方式便不适用于这款游戏;也就是说对于那些受欢迎游戏的续集作品,往往更加适合采用瀑布模式。

但是绝大多数游戏设计师都希望能够制造出富有创造性的新游戏。

为何本课程主要关注非数字游戏…

也许有些人喜欢制造桌面游戏,所以并不关心电子游戏的制作。但是对于那些热爱电子游戏制作的人来说,便会好奇为何我们在这个课程里花了这么多时间都在阐述如何制作桌面 游戏和纸牌游戏。而现在你们应该知道答案了吧:因为对于纸牌游戏和桌面游戏来说,迭代的方法更加快速且便宜。就像我们曾在之前的课程提到的:你可以花15分钟制作一款桌 面游戏。游戏编程需要很长时间。所以你需要尽可能地先在纸上绘出游戏原型,因为15分钟的纸上原型绘制以及1个小时的游戏测试,都可能帮助你节省数个月的编程工作。

我们将在后面的课程中讨论纸上模型的相关细节问题,即包括传统桌面游戏和其它类型的电子游戏。

这也是我们的课程为何侧重于非数字游戏,特别是桌面游戏和纸牌游戏的另一大原因。这是一个关于系统设计的课程,也就是关于创造游戏规则的课程。桌面游戏的规则总是很直 白。虽然其中也包含了一些实质性元素,但是说实在的,玩家的游戏体验几乎完全依靠于游戏规则和玩家交互性。如果游戏规则没有说服力,那么游戏也就不会有趣,所以我们在 制作游戏的过程中应该更加关注于游戏规则和玩家体验间的联系。

但是在电子游戏中却不是这样。许多电子游戏中都带有一些让人印象深刻的技巧(如现实般的物理引擎),图像和音效,以此掩盖它们陈旧的游戏设置。而且电子游戏的制作过程 都很漫长(归因于编程和艺术/音频的制作),所以只花十周的课程根本不可能制作出一款电子游戏。

在角色扮演游戏中,游戏规则和玩家体验也是个让人苦恼的组合。你们中有许多人也许对角色扮演游戏设计感兴趣,所以你们可能会对游戏规则和玩家体验感到陌生。但是不管怎 样,你都需要牢记,角色扮演游戏是故事的集合体(并且由一大规则系统去限制游戏界限)。同样地,再优秀的系统也会因为玩家拙劣的讲故事能力和游戏技巧而黯然失色,而再 糟糕的系统也可以因为玩家的高超技术而生辉。如此,我们选择,或者只是在最初阶段,避开这些游戏类型。

尝试

如果你还未玩过之前那款只花了你15分钟而完成的游戏,那么就去尝试看看。当你在玩的时候,问自己:比起你曾经发布过的最受欢迎的游戏,这款游戏是更加有趣还是相对无聊 ?为什么?你是否能够改变并完善它?你无需坚持到游戏最后,只要找到感觉,知道如何做才能更好地改进这款游戏,你便可以停止尝试。

在你退出游戏后,至少针对游戏做出一个改变。你可以改变游戏运转规则,或者为玩家添加一个新的互动方式。你还可以改变纸牌的移动空间等等。不论你是出于何种原因做了何 种改变,你都必须在改变后再次尝试游戏。记下变化。关于你所做的改变是否对游戏有帮助。你是否可以根据这次的改变而设想下一次的改变?如果游戏因为改变而变得更加糟糕 ,你是否会将规则恢复到之前的样子,还是按照其它方式再次进行调整?

我们将在后面的课程中进一步阐述游戏测试过程中的细节问题。而现在,我只是希望所有人都能够克服一种恐惧,即“如果我尝试自己制造的游戏结果会怎样?会不会很失望?” 我猜测你根据课程一所设计游戏失败几率非常高(我们怎么可能只花15分钟而制造出一款类似于《战争机器》的游戏?)。但这并不表明你就是一个“糟糕的设计师”,只能说明 如果你能够投入更多时间,并反复进行迭代,那么你一定能够制造出一款非常优秀的游戏。

经验教训

从今天开始你应该明白一个道理,游戏迭代次数越多,它就会变得越优秀。实际上,优秀的设计者并不擅于制造好游戏。相反地,他们更擅于将一款糟糕的游戏进过反复迭代,而 让其变成真正优秀的游戏。

以下是两大必然结果:

你希望能够尽早想出一个可游戏的游戏原型。越快测试你的观点,你便拥有更多的时间去完善游戏。

从时间来看,短而简单的游戏比起长而复杂的游戏,能够提供更棒的游戏体验。也就是如果一款游戏需要你花费10个小时的时间,那么你将没有多余时间去进行游戏迭代,而你将 更加倾向于另外一款只需要5分钟便能完成的游戏。特别是在后面即将开始的设计项目课程中,你更需要牢记这一点。

家庭作业

我将在下一个讨论游戏形式因素的课程中涉及:

《Challenges for Game Designers》第二章节(Atoms)。这部分内容可以作为下周我们将分析的“游戏”概念的过渡点。

Doug Church的《Formal Abstract Design Tools》。这篇文章是基于Costikyan的《I Have No Words》,而提供一些有用的道具帮助我们分析并设计游戏。文章里提到了许多关于 电子游戏的例子,请试想一下这些概念是否也适用于其它类型的游戏。

读物告示

本文要涉及到的读物是Doug Church的《Formal Abstract Design Tools》。我想提些有关这篇文章的东西。首先,他提到了游戏中的三个层面值得在设计中考虑:

1、玩家意图的定义是玩家规划和执行自己的计划及目标的能力。在本课程随后的内容中,我们还会阐述这方面的内容,但是现在要先让你明白,在许多游戏中这个层面很重要,可 以让玩家形成行动计划。

2、可察觉后果在该文章中的定义是游戏对玩家行动的清晰回应。这里的“清晰”是很重要的,如果游戏做出了回应但是你不知道游戏的状态已经发生了何种改变,那么你可能很难 将你的行动同这些行动的结果联系起来。我想指出的是,“可察觉后果”有个更常见的名称:反馈。

3、故事指的是游戏的叙事线路。应当注意的是,游戏可能包含两个不同类型的故事:内在故事(游戏邦注:由设计师创造)和表面故事(游戏邦注:由玩家创造)。比如,当你告 诉好友近期玩的某款游戏以及在玩游戏过程中经历的事情:“我控制了整个非洲,但是还是无法将蓝方赶出扎伊尔。”,这时发生的便是表面故事。内在故事便是我们通常认为的 游戏的“叙事”,比如“你扮演着某个勇敢的骑士,在邪恶巫师的城堡中探险。”。Doug的观点是,内在故事与意图和结果相对立,也就是说,游戏的内在故事越强,玩家对游戏 结果的影响就越小。当Costikyan表示游戏并非故事时,我认为Doug更好地阐述了Costikyan的看法。

这里我将距离说明为何玩家意图和可察觉后果很重要。考虑以下情况:你正在玩一款第一人称射击游戏。你走向一面墙,上面有个开关。你拨弄开关。什么都没有发生。但是,事 实上发生了某些事情,但是游戏没有给你提供任何发生某些事情的迹象。或许是关卡中某个地方的一扇门开启。或许你只是将大量的怪物释放到这片区域中,只要你离开目前所处 的房间就会碰上它们。或许有一系列的开关,它们必须形成某种开启和关闭组合(游戏邦注:或者他们需要以正确的顺序来触发)才能够打开过关的路径。但是所有这些你都无从 知晓,因而你会产生挫败感,现在你必须彻底搜索已经到过的所有地方,只是为了看看拨动开关是否产生了某种效果。

要如何解决这个问题呢?添加更好的反馈。一种方法是想玩家提供地图,当开关被拉动时在地图上向他们呈现发生变化的区域。或者,用简短的过场动画展示某个地方的门开启。 我想你应当还能想出更多的其他方法。

Doug在文章末尾的有趣评注中还提到了另一个主题,那就是他对游戏测试的评价。这是该文章中有关迭代设计的部分,这正是我们所讨论的话题。

现在,我确信这个评注有点开玩笑的成分,但是我们可以发现其中潜藏的价值。这篇文章中有个小错误:你只有通读整篇文章时才能够看到评注,而这时再采取做法已经为时过晚 。如果Doug想要重新规划自己的设计,你会给他提怎样的建议呢?

游戏质量

我曾在之前的文章中坚持认为关键词汇很重要,同时我又不断地声称完全定义“游戏”这个词是不可能的。让我们先解开这个貌似真实的矛盾。

如果快速浏览下我之前列举的那些定义,就可分离出可能适用于游戏每个定义的特性。我们可以在其中看到某些不断出现的要旨:游戏有规则、冲突、目标、决策和不确定的结果 。游戏是活动,它们是人为的、安全的和外在的普通生活,它们是义务无偿的,它们包含伪装、呈现和模拟元素,它们的效率很低,它们是艺术,它们是封闭式的系统。花点时间 想想,还有许多所有游戏共有的东西。这为我们认识各游戏机制提供了出发点。

我将这些元素称为“正式元素”,并不是因为它们同穿正装和打领带有什么联系,而是因为他们在数学和科学上显得“正式”,是些可以明确定义的东西。这些内容可以被视为“ 原子”,因为这些是游戏的最小组成部分,可以被分离出来独立研究。

什么是游戏的原子元素?

这取决于你询问何人。我见过许多种分类方案。就像“游戏”的定义一样,所有的方案都不完美,但是通过对这些内容的研究,我们可以发现某些新的要旨。如果我们有制作游戏 的计划,这些新的结果就可以让我们这些游戏设计师需要创造的东西得到提升。

以下内容中有些属于游戏的部分内容,有些是设计师在研究这些原子时需要考虑的东西。

玩家

游戏支持多少个玩家?玩家的数量是固定的(比如是能有4个玩家),还是可变动的(比如玩家数可以是2到5个)?玩家能否在游戏过程中加入或离开?这会对游戏产生何种影响?

玩家间是什么关系,是团队合作还是独自作战?团队之间是否可能有差异?以下是某些玩家结构范例,但并非只有这些:

klondike-solitaire(from androidapproundup.com)

1、单人(1个玩家 VS 游戏系统)。范例包括纸牌游戏《Klondike》(游戏邦注:有时就称为“单人纸牌游戏”)和电子游戏《扫雷》。

2、单对单(1个玩家 VS 1个玩家)。象棋和《Go》是典型的范例。

3、PVE(多个玩家 VS 游戏系统)。这种形式在《魔兽世界》等MMO游戏中很常见。也有些纯合作桌游,比如Knizia的《指环王》、《魔镇惊魂》和《瘟疫危机》。

4、单对多(1个玩家 VS 多个玩家)。桌游《苏格兰场》便是此类结果的绝佳例证,单个玩家需要对付整个侦探团队。

5、自由混战(1个玩家 VS 1个玩家 VS 1个玩家VS…)。这可能是多人游戏采用的最普遍的玩家结果,到处都可以看到,从《大富翁》之类的桌游到多数第一人称射击电子游戏中 的“多人死亡竞赛”。

6、独立个人对系统(1个玩家 VS 一系列其他玩家)。赌场游戏《黑杰克》便是例证,游戏中的“庄家”是个单独的玩家,对阵许多其他的玩家,但是他所对阵的玩家之间互不干 涉且毫无联系。

7、团队竞赛(多个玩家 VS 多个玩家 VS 多个玩家 VS…)。这也是中常见的结构,使用于多数团队运动、桥牌和《黑桃王》等纸牌游戏、第一人称射击游戏中“夺取旗帜”模式 等基于团队的在线游戏和许多其他游戏。

8、捕食者和猎物循环。玩家围成一个真实或虚拟的圈。每个人的目标都是攻击左边的玩家,防御来自右边玩家的攻击。游戏《暗杀》和卡片交易游戏《Vampire: the Eternal Struggle》使用的都是这种结构。

9、五角星。我首次看到这种结构是5人《万智牌》的变体。玩家的目标是消灭并非属于己方的两个玩家。

目标

游戏的目标是什么?玩家努力实现什么?在设计游戏时,如果你遇到麻烦不知道从何下手的话,这通常是你可以提出的首批问题之一。一旦你明确了目标,许多其他的正式元素似 乎就会自然浮现眼前。以下是某些常见的目标(游戏邦注:同样,并非所有种类的游戏目标):

1、捕捉/摧毁。消灭游戏中对手的所有单位。象棋和军旗是为人所熟知的范例,你必须消灭所有敌方的棋子才能获得胜利。

2、领地控制。玩家的专注点不一定是摧毁对手,也可以是控制棋盘上的某些区域。《大战役》和《强权外交》便是范例。

3、收集。卡片游戏《Rummy》及其变体的胜利条件是收集套卡。《种豆子》中需要玩家收集各种豆子。许多平台游戏(游戏邦注:比如《Spyro》系列)包括某些玩家需要收集特定 数量的分散物品才能通过的关卡。

4、解决问题。桌游《妙探寻凶》便是此类游戏的范例,游戏的目标是解决谜题。鲜为人知但更为有趣的范例包括《魔幻城堡》和《Sleuth》。

5、追捕/竞速/逃跑。通常来说,在此类游戏中你必须奔向或者逃开某些东西,比如娱乐场游戏《Tag》和电子游戏《超级马里奥兄弟》。

6、空间排布。许多游戏以元素布置为目标,包括非数字化游戏《Tic-Tac-Toe》和《Pente》以及电子游戏《俄罗斯方块》。

7、建设。“摧毁”的反方向,你的目标是将自己的角色提高或资源建设到某种程度。《模拟人生》采用的便是这种元素,桌游《卡坦岛》也是如此。

8、其他目标的反面。在某些游戏中,当一名玩家采取了游戏规则禁止的做法,游戏结束,这名玩家便是输家。范例包括肢体灵活游戏《Twister》和《层层叠》。

settlers-of-catan(from appadvice.com)

规则(机制)

我们曾经提到过,规则有三种不同的类别:设定(游戏开始之初就做完的事情)、游戏过程(游戏期间发生的事情)和决定(导致游戏结束的条件以及基于游戏状况决定结果的方 法)。

有些规则是自动的,它们在游戏的某个时刻被触发,与玩家的选择或互动无关(游戏邦注:比如“在回合开始时抽取一张卡片”或“计时奖励分数每秒减少100点”)。其他的规则 决定了玩家可以在游戏中做出的选择或采取的行动,以及这些行动对游戏状态的影响。

让我们再进一步挖掘。Salen和Zimmerman的《Rules of Play》将规则分为三种类型,包括操作规则、建构规则和暗示规则(游戏邦注:这些并非行业内的标准属于,因而在这里概 念比术语更加重要)。为阐述其中的概念,我们以《Tic-Tac-Toe》的规则为例:

1、玩家:两名

2、设定:绘制3X3的格子。选择一名玩家先画X,他的对手画O。

3、游戏过程:到你的回合时,使用自己的标志来标记某个空白的地方。随后轮到对手采取同样的做法。

4、决定:如果你的3个标志连成一条线(游戏邦注:包括直线或对角线),你就获得了胜利。如果棋盘被填满而且无胜利者,这便是一场平局。

这些便是《Rules of Play》中所谓的“操作规则”。思考片刻,这些是游戏中仅有的规则吗?

乍看之下,似乎便是如此。但是假如我认识到自己即将失败,拒绝在自己的回合中展开行动,那又如何呢?规则中并没有明确的时间限制,所以我可以无限期地拖延以避免失败, 此举并没有违反游戏的“规则”。但是,在现实的游戏中,会暗中规定合理的时间限制。这并非游戏的正式规则(即操作规则),但是仍属于《Rules of Play》中所述“暗示规则 ”的部分。这里的要点在于,玩家在玩游戏时会达成某些不成文的社交契约,这些内容尽管并未特别说明,但仍然可以为玩家双方所理解。

即便是游戏中的正是规则也包含两个层面。3X3棋盘和“X”及“O”标志是这款游戏的特别之处,但是你可以将它们抛弃。可以将棋盘重新构建成1到9的范围,将空间连线转变成其 他的数学特性,你就可以获得《Three-to-Fifteen》。尽管《Tic-Tac-Toe》和《Three-to-Fifteen》有着不同的操作方式和外观,但是潜在的抽象规则是相同的。当我们提及“规 则”时通常不会考虑到这些抽象术语,但是它们确实存在于游戏的外表之下。《Rules of Play》将这些称为“建构规则”。

区别这三种类型的规则有用吗?我觉得知道这些内容很重要,有两个原因:

“操作规则”和“建构规则”间的差异可以帮助我们理解为何某款游戏与其他游戏相比会显得有趣。经典街机游戏《Gauntlet》的游戏玩法同第一人称射击游戏《毁灭战士》极为 相像,最大的差异就在于镜头位置的不同。对于那些玩现代桌游的人来说,《波多黎各》和《银河竞逐》也极为相似。这种相似度可能不会立即显现出来,因为游戏的外观看上去 有很大差别,你需要考虑到游戏状况和规则才能够发现其中的相似之处。

许多第一人称射击游戏包含有一个规则,那就是当玩家被杀死之后,他们会在特定的已知地点重生。其他的玩家可以站在那个地点附近杀死任何重生的玩家,他们根本没有做出反 应的机会。这便是所谓的“复活杀戮”,为众多玩家所诟病。复活杀戮是否属于游戏的一部分(因为这并没有触犯规则)?这是种优秀的战略还是作弊行为?这取决于你问的人, 因为它属于游戏中的“暗示规则”。当两个玩家在不同的暗示规则下操作时,你会最终发现某个玩家控告另一个玩家作弊,而另一个玩家会狡辩称他们并没有触犯游戏规则,妨碍 他们取得胜利的努力是不合理的行为。这里的经验就是,游戏设计师精确定义尽可能多的此类规则很重要,以避免游戏过程中的规则争辩。

资源和资源管理

“资源”是个广义的类别,我用他来指代所有处于玩家控制之下的东西。很显然这包括某些具体的资源(游戏邦注:《卡坦岛》中的树木和麦子,《魔兽世界》中的生命值、魔法 值和货币),但是资源也包含其他处于玩家控制之下的东西:

1、《大战役》中的领土

2、《Twenty Questions》中的剩余问题数量

3、电子游戏中可以被拾取的物品(武器和升级道具)

4、时间(游戏时间或现实时间)

5、知晓的信息(《妙探追凶》中你已经排除的嫌疑犯数量)

玩家控制的是何种类型的资源?在游戏过程中如何对这些资源进行操作?这是游戏设计师必须清晰定义的东西。

游戏状态

Texas Hold’em(from itunes.apple.com)

某些“资源类”的东西并不属于单个玩家,但是仍然属于游戏的一部分,比如《大富翁》中的无主地产和《德克萨斯扑克》中的公牌。游戏中的所有东西,包括当前的玩家资源和 所有其他的东西,这些东西所构成的游戏在某个时刻的状况就是所谓的游戏状况。

在桌游中,精确定义游戏状况不总是必要的,但是有时思考这个方面很有用。归根到底,规则的含义就是游戏从一种游戏状况过渡到另一种游戏状况所采用的方法。

在电子游戏中,必须有人定义游戏状况,因为它包括所有电脑必须追踪的数据。通常情况下,这个任务会落到程序员身上,但是如果游戏设计师能够清晰地定义整个游戏状况,可 以很大地改善编程团队对游戏的理解。

信息

每个玩家可以看到多少游戏状况?改变玩家可以触及的信息数量会对游戏产生很大的影响,即便所有其他的正式元素都维持不变。以下是某些游戏中使用的信息结构:

1、有些游戏会提供全部信息,所有的玩家可以在任何时刻看到全部的游戏状况。经典桌游象棋和《Go》便是范例。

2、游戏包含某些每个玩家独有的信息。在扑克和其他卡片游戏中,每个玩家都有一手只有他们自己能够看到的牌。

3、一个玩家可以拥有自己的保密信息,但是其他玩家不能。这通常出现在一对多的玩家结构中,比如《苏格兰场》。

4、游戏本身包含某些所有玩家都无从知晓的信息。《妙探追凶》和《Sleuth》的胜利条件是玩家发现游戏中的隐藏信息。

5、这些方式的结合。许多即时战略电脑游戏设置有“战争迷雾”,向所有玩家隐藏地图上的某些地方,直到他们派某个单位到底视野范围才能看到。因而,有些信息是向所有玩家 隐藏的。除此之外,玩家不能看其他人的屏幕,因而每个玩家都不会知道对手的信息,自己的信息也不会被对手所知晓。

顺序

玩家以何种顺序来采取行动?游戏如何从一个行动流向另一个行动?根据所使用的回合结构不同,游戏的运行方式也有所不同:

1、有些游戏是纯粹的回合制:在游戏中的任何时刻,只有1个玩家在自己的“回合”内采取行动。当他们结束之后,回合转向其他玩家。多数经典桌游和回合制战略游戏都采用这 种方法。

2、有些游戏基于回合制,但是有同时进行的玩法(游戏邦注:每个人同时在回合内采取行动,通常是写下他们的行动或者将行动卡片面朝下盖着然后同时翻开)。桌游《强权外交 》采用的就是这个机制。还有个有趣的象棋变体游戏,同时写下他们回合内的行动然后翻开,在同个回合进入相同格子的双方棋子都算死亡,这增添了游戏的紧张感。

强权外交(from rankopedia.com)

3、有些游戏是即时性的,玩家以尽量快的速度开展行动。多数面向动作类的电子游戏都采用这种方法,但是某些非数字化游戏(游戏邦注:比如卡片游戏《Spit》和《Speed》) 也采用这种方法。

4、其他变体。对于基于回合的游戏而言,玩家要以何种顺序来轮流行动呢?以顺时针方向轮流采取行动是普遍的做法。以顺时针顺序随后跳过首个采取行动的玩家以减少先手优势 也是在许多现代桌游中采用的改良方法。我也见过某些随机决定回合顺序的游戏,或者玩家支付其他游戏中的资源来获得先手或最后行动的特权,或者根据玩家的地位来决定回合 顺序(游戏邦注:比如目前胜利的玩家最先或最后行动)。

5、回合制游戏可以被进一步修正,比如加入明确的时间限制,或其他形式的时间压力。

玩家互动

游戏的这个层面经常被忽略,但是却是值得考虑的方面。玩家如何同其他人互动?他们如何影响其他人?以下是某些玩家互动的范例:

1、直接冲突(我攻击你)

2、谈判(如果你支持我进入黑海,下个回合我会帮你进入开罗)

3、交易(我用木材换取你的麦子)

4、信息共享(我上个回合看过那篇被覆盖的区域,如果你进入就会触发陷阱)

主题(或叙事、背景故事及场景)

对职业故事作者来说,以上术语的含义之间有明显的差别,但是对于我们而言,它们可以互换,都是指游戏中完全不直接影响游戏玩法的部分。

如果这些内容与游戏玩法无关,那么为何要设置这些内容呢?主要原因有两个。首先,场景提供了游戏的情感连接。我发现自己对象棋棋盘上卒的关注并不像自己对《龙与地下城 》中的角色关注那样深。虽然这不一定能够让一款游戏比另一款游戏更好,但是确实可以更容易地让玩家在游戏中投入情感。

第二个原因是,精心选择的主题能够让游戏学习和玩起来更加容易,因为规则更易于理解。象棋中棋子的移动规则与主题毫无相关,因而学习象棋的玩家必须死记这些规则。相比 之下,桌游《波多黎各》中的角色与他们的游戏功能都存在联系:建筑工人可以帮助你建造建筑物,市长可以招募新定居者等。游戏中多数的行动都很容易记住,因为它们同游戏 的主题存在某些联系。

波多黎各-iOS(from boardgamegeek.com)

游戏系统

对于这些正是元素,我希望你能够注意两点。

第一,如果你改变任意一个正式元素,可能产生出差异极大的游戏。游戏中的每个正式元素都深层次地影响玩家体验。在设计游戏时,思考所有的这些元素,确保每个都做出慎重 的选择。

第二,注意到这些元素是相互关联的,改变其中一个可能会影响其他元素。规则控制游戏状况的改变。信息有时会变成资源。顺序可能产生不同类型的玩家互动。改变玩家数量可 能影响游戏的目标。

正因为这些部分之间相互关联的本质,你可以将任何游戏当成系统来构建。词典对词语“系统”的释义之一是:将事物各部分结合起来形成复杂的整体。

事实上,一款游戏可能包含多个系统。《魔兽世界》有战斗系统、任务系统、公会系统和聊天系统等。

系统的另一个特性是,很难仅仅通过定义来完全理解或预测它们,看到行动中的系统你可以获得更深层次的理解。以抛掷动作的肢体系统为例。我可以给你一个定义球体抛出路径 的数学方程式,你可以由此预测到它之后的行为,但是如果你亲眼得见某人扔出球体,会更容易地理解整个过程。

游戏跟上述情况很像。你可以阅读规则和定义游戏中的所有正式元素,但是你需要体验游戏才能够真正理解游戏。这就是多数玩家在玩过《Tic-Tac-Toe》和《Three-to-Fifteen》 后才明白二者间的相似性的缘由。

游戏的批判分析

何谓批判分析?我们为何需要批判分析?

批判分析不只是游戏评论。我们关心的不是得到了几颗星、游戏评分多少、游戏是否有趣、是否能说服用户购买游戏这些内容。

批判分析不只是列举出游戏中错误的做法。这种语境下,“批判”这个词的意思不是“挑错”,而是就游戏进行彻底及毫无偏见的审视。

批判分析在讨论或比较游戏时很有用。你可以说“我喜欢卡片游戏《Bang!》,因为它很有趣”,但是这并无法帮助我们这些设计师理解为何游戏很有趣。我们必须审视游戏中的各 个部分以及它们互动的方式,才能够理解每个部分是如何与玩家体验产生联系的。

在游戏开发过程中检视我们的工作时,批判分析也很有用。对于一款你正在制作的游戏,你要如何知道要添加或移除哪些内容才能够提升游戏质量呢?

批判分析游戏的方法有许多种,在此我提供了一个三步骤过程:

1、描述游戏的正式元素。此刻无需进行解释,只要找出即可。

2、描述执行正式元素后的结果。不同的元素间如何互动?游戏的玩法是什么?是否有效?

3、努力去理解为何设计师选择这些元素而不是其他元素。为何要使用这种玩家结构?为何要使用这套资源?如果设计师做出不同的选择,会发生什么事情?

在批判分析各个阶段期间需要向自己提出的某些问题如下:

1、玩家面对何种挑战?玩家可以采取哪些行动来克服这些挑战?玩家之间如何互相影响?

2、玩家是否会认为游戏是公平的?(游戏邦注:游戏实际上可能公平也可能不公平,玩家对游戏公平程度的看法可能与现实有所差别。)

3、游戏是否具有再玩性?是否有多条通向胜利的途径、不同的起始点或者导致每次游戏体验有所不同的可选规则?

4、游戏的目标用户群是什么?游戏是否适合目标用户?

5、游戏的“核心”是什么,也就是你一遍遍做来呈现主要“趣味性”部分的事情是什么?

内容归纳

今天我们谈到了许多内容,主要可以归结如下:

1、游戏是系统。

2、玩游戏可以让你更容易地理解游戏。

3、分析游戏需要你审视所有游戏正在运行的部分,弄清楚他们如何配合并产生出玩法体验。

4、设计游戏需要创造出所有游戏的部分。如果你仍未以某种方式定义游戏的正式元素,那么你并非真正在制作游戏,你只是有个想法而已。这确实很不错,但是如果想要把它制成

游戏,你就必须进行真正的设计。

设计实验

我希望你能够从接下来的设计实验中找到乐趣,但首先要根据你之前的游戏设计经验选择难度等级。

多数战争主题游戏的目标要么是领土控制要么是捕获/摧毁(游戏邦注:这两类在上文中描述过)。在这个挑战中,你将越过这些传统界限。你应当设计包含下述内容的非数字化游 戏:

1、主题必须与第一次世界大战有关。玩家的主要目标不是领土控制或捕获/摧毁。

2、你不能使用领土控制或捕获/摧毁作为游戏动态。也就是说,你的游戏不能包含任何概念的领土或任何形式的死亡。

3、除了上述要求之外,玩家还不能有直接冲突,冲突只能是间接的。

有关研究的声明

你或许需要做某些研究才能够完成设计项目(游戏邦注:即便只是搜索维基百科来寻求灵感)。这是典型的游戏设计。许多人将游戏设计师想象成那种整天只是坐在桌旁思考的人 ,最后忽然站起来然后大吼:“我想到了某个绝妙的游戏想法!有忍者、激光恶化太空!程序员和美工们,马上行动将游戏构建起来!我会接着坐在这里构思另一个绝妙想法,同 时还能够得到之前5个创意的版税。”但这与现实相差甚远。许多设计需要涉及到细节,不仅要定义规则,还要进行研究确保规则适合参数和项目。

IP法律声明

你要如何保证自己免受他人窃取基本创意的威胁呢?他们可能会将其转变成可运行和销售的游戏,而后你一无所获。

Dan Rosenthal是本课程的参与者之一,他写了篇文章细致分析了与游戏相关的知识产权法。文章确实是以美国为例,但是核心想法应当可以应用于其他国家:

记住,想法并不享有版权,它们不能被注册成商标,不能秘密交易,也很难申请成专利。你无法以某种方法来保护它们,你不应当在这方面费尽心机,你应当做的是尝试构思出新 想法,开始就优秀的想法展开工作。不要因为在此课程中看到的内容而焦虑不安,“Ian说我应当将自己的作品提交到论坛上,但是我想到了某个很棒的想法,不希望它被他人窃取 。”这种想法是毫无必要的。在游戏中,想法是种很普遍的东西,与执行想法的价值相比,想法本身根本毫无价值,你应当努力将想法开发成某些真正能让你赚到钱的东西。但是 最为重要的是,我们的行业很紧密且极具协作性。你会发现人们在GDC上分享他们的想法,各工作室之间会协作开发项目,或者使用来自某款游戏的灵感来提升另一款游戏的质量。 不要为此而争斗。这就是事态的运转方式,以宽广的胸怀包容这一切,你会获得更多的好处。

限制条件

很多时候,我们会发现天马行空地想像一番之后,设计游戏时却无从下手。这时候,添加一些限制条件也许会让难题不那么棘手。这好像跟我们的解题思维背道而驰了——原来的 问题都解决不了了,再加限制条件不是雪上加霜?道路已经够曲折了,还添堵?未必,至少设计游戏时不总是这样。

为了便于理解,我们可以把游戏设计当作一个在游戏中依次叠加限制条件的过程。你每增加一条新的规则、定义一种新资源,对玩家来说都是增加了一个限制条件。在游戏设计的 开头,你什么规则也没有,而玩家什么都能做;到了结尾,各种各样的限制条件根据“有趣”的方式来定义玩家的体验。

现在你不妨思考一下电子游戏中所谓的“开放世界”是什么。玩家的一般反应就是,游戏充许你做任何事,给予玩家完全的自由,这也是乐趣所在。然而,严格地说,游戏并没有 给予玩家彻底的自由。玩家实际上受到储多约束:玩家的移动必然遵循一定的方式,能与玩家发生互动的必然有确定的对象,自行移动对象必然受某种计算机算法控制。玩家有多 种选择和相对开放的目标,但可以肯定的是,确实存在许多让玩家产生“无拘无束、随心所欲”这种错觉的限制条件。

如果你认同这种解释——游戏设计就是创造限制条件,那么你可以看看外界施加的限制条件是否可以辅助初步设计。通过添加限制条件,要做的设计工作就没那么多了。这就解释 了我刚才提出来的悖论。

限制条件还可以为你的创意提供依附点。如果我只想着做游戏而不考虑限制条件,那么许多人都会傻坐着像只无头苍蝇,不知所往。而通过添加限制条件(如“第一次世界大战” ),这个问题就不再是“要做什么”了,而是“根据这个主题我能做什么”。后者显然比前者更容易回答。

事实上,现实的设计大多数与限制条件有关:比如,发行商要求游戏采用某个原创主题或设某种类型或在某个时间/预算内完成。我提这个的原因之一是,要提醒你这些限制条件虽 然看起来很可笑(“我得以‘我的小马’概念为基础做一款DS游戏?”),但实际上限制条件常常能让设计师的日子好过得多。

我提这个的另一个原因是,你的生命当中很少有不受来自他人的限制的时候(特别是“独立”游戏开发者和业余设计师),如果你的工作起步有困难,出路之一就是给自己添加一 些限制条件。比如,给自己一个时间限制(游戏邦注:例如“Game Jam”大赛一般要求参与者在24小时或48小时内制作一款游戏);选择一个自己有兴趣的题材作为游戏的主题; 挑选一个你喜欢的核心机制进行开发。这完全是随意的,但如果你不知道你的游戏该往哪个方向走,坚持下去,选择一个额外的限制条件让自己前进。(重复再重复,之后你总是 能够排除那些武断的限制条件,如果你发现所选的条件阻碍了游戏设计的话。)

创意生成

设计的第一步,你必须想出一个基本的游戏创意。不一定要完全成形的,但至少要有一个基本的概念。以下我无顺序地列举了几种创意生成的方式:

体验法。你想让玩家有什么感觉?你想让玩家有什么反应?游戏体验应该是怎么样的?从玩家体验的角度出发,构想一套能达到期望美学的规则。想一想你自己玩游戏时的最好体 验,即什么游戏规则能带来那种体验?

规则法(系统法)。从你在日常生活中观察到的规则或系统出发,特别是那些需要人们做出有趣的决定的。观察你周围的世界,思考一下什么系统能做成好游戏?

改良法。从现存的、确定的设计出发,然后将其调整提升(“模仿-加工-生成”)。这种方法常用于制作游戏续篇。什么游戏你认为有潜力,但价值还没完全发挥出来,你要怎么 改良它?

技术法。从技术,如新游戏引擎(电子游戏)或特别的游戏部件(如角色可旋转的基部)出发,将其运用于你自己的游戏中。你生活的地方有什么东西还没出现在游戏中,但可以 添加到游戏中?

拾遗法。从其他资源中搜集材料,如其他游戏还没用上的艺术作品或游戏机制。利用这些设计一款游戏。你有没有美术文件夹或者早期游戏设计时用到但最终没有做出成品的材料 ?大众化的作品,比如文艺复兴时期的作品怎么样?围绕这些材料你怎么设计游戏?

剧情法。从游戏的剧情出发,然后找到匹配的规则,做成一款剧情导向型的游戏。什么类型的故事适合做成游戏?

市场研究法。从市场研究出发:你可能知道某类人群还没被开发,可以针对这类人群设计游戏;或者你只知道当前某个主题很热门,且某段时间内不会有太多的游戏出来填补市场 ,这就是个时机。你怎么把这个信息转化为可玩的游戏?

将以上方法组合使用。比如,从核心美学和剧情出发,你可以制作出一款兼顾剧情和玩法的综合型游戏。

当你想到新的游戏创意时,你的起点是什么?

其他创意生成的方法

如果你遇到了设计瓶颈,你可以找到许多应对的策略,以下列举了一些:

收集法。将你的所有关于游戏、机制、剧情等等想法收集成册。时不时的浏览一下,看看有没有什么“老菜”可以拿出来“新炒”。每当你想到暂时用不上的创意,就把它记录下 来。

随意思物法。随便想到什么东西,想方设法把它安到游戏中去。

温故知新法。从更深的层面上去研究当前的游戏,你可能就会想到新的点子了。

基础法。思考游戏中的正规元素。比如,玩家的目标是什么?规则?资源?等等。注意,为了创造游戏,无论怎样都要明确定义这些东西,所以集中注意力思考这些东西,你可能 会发现新的问题。

brainstorm(from blog.lib.umn.edu)

头脑风暴法。你可以一个人做,也可以和一帮人一起做。有些人非常信奉这个方法,有些人却很质疑其产生的结果。我能说的就是,结果是不可测的,但这确实是种研究与开发的 方式。

纠错法。批判地看待你的游戏。你可能有一本笔记本记录了其他设计师(包括我)多年的心得体会,但你也需要写一本自己东西(无论你是不是要拿去出版,总之记下先)。当你 发现有些东西不太管用,并且你认为你可以识别其根源,那么就把引发问题的原因当作设计法则(或至少是指导)记录下来。如果你不知道根源,也还是记下来吧,定期地看看, 没准就让你找到答案了。

玩游戏法。玩很多游戏!不过,要带着研究的目的玩游戏,而不要像普通玩家那样,为了娱乐而玩游戏。另外,批判地玩游戏。问自己该游戏的设计做了什么选择,为什么,是否 有效。尝试你不喜欢或从来没玩过的游戏类型,找出其他人觉得好玩的原因。再者,已经发布的游戏指南也值得一读,那些基本上就是一份完备的设计文件了,所有游戏机制的细 节一目了然!

最后,勤加练习,熟能生巧。在自己的项目中好好干。你制作的游戏越多,你就越会制作……其他艺术也是如此。

原型制作

记住,你的想法重复构想得越多次,最终的游戏就越好。一旦你有了基本想法,下一步就是尽快将其转化为尽可能廉价的可玩模型。这么做可以为测试和返工节省下大量时间。

对于存在高设计风险的部分,重做是最关键的环节。“模仿-加工-生成”类的游戏大多是从已经存在了的游戏中的玩法提炼出来的,所以快速原型就不是那么重要了。这不意味着 “克隆”来的游戏就不必重做了,而是你应该有选择性地把创意过的部分拿出来重做。为了应对当下的挑战,牢记于心吧。

原型制作的“法则”

请记住制作原型的目的是最大化迭代循环次数。推论:尽量减少每次重做所需的时间。现在,考虑一下各个重复循环一般包含的四个步骤:设计、原型、测试和评估。这四个步骤 ,哪一步能节省时间?

设计游戏的规则时,如果不折中你的目标,确实省不下时间,因为匆匆忙忙是出不了好创意的。

通过制定高效的时间表和设计测试(游戏邦注:即在最短的时间内给出最多的信息)可以减少花在游戏测试上的时间。但仍然有一个固有的限制,在某个时间点上,你就是得花这 么多时间来测试游戏,不能再仓促了。评估倒是用不了太久,你只是根据测试结果,简单地回答是否来决定游戏好不好。所以也不可能从中挤出什么时间了。

所以,节省时间的重任就落到原型制作这个步骤上了。

当你制作可玩的原型时,请记住以下几点:

能快则快。怎么快怎么来。只要省钱省事,丑点没关系。

删繁就简。只做评估游戏必须具备的部分。如果你打算测试新的战斗系统,那么你不需要制作出整个探测系统。如果你在制作卡片游戏,徒手在卡片上完成就好,没必要输入到PPT 上、打印在硬纸片上然后手把手地剪下来。精工细活另安排时间去做,游戏设计的早期阶段就没必要在这上面耗了。

容易调整。你做测试时,会发现不少问题,所以你得保证原型容易调整。

以上原则把设计师推向了一个不可避免的方向……

纸上原型

你可以叫这个东西“纸张”、“纸板”或“非数码”或“模拟”等等,随便你怎么称呼,反正就是要有一个有实物的、摆到桌面上、不用电脑(或至少不需要代码)也能玩的游戏 。编程很好很强大,但与纸上原型相比,太慢太贵。纸上原型具有以下优点:

划算。大多数系统只要一支笔加几张纸就能完成了,当然,后面我会告诉你该花的钱花到什么地方去了。

省时。你不需要在编程、布局或美术设计上浪费时间。只要在碎纸片上写个把字就够了。

容易修改。不喜欢某个数字?擦了另写一个。

丢掉不心疼。结果你的想法用不了?好吧,浪费了半小时。了不起,就像画打草稿:如果第一次画的不太好,浪费掉的只是那几秒钟,涂掉重来。

普适性。纸上原型基本上可以模拟所有系统,甚至是那些我们一般认为与只针对电子游戏的系统。

通过制作一些可玩的原型,你必须切实地设计出系统。你不能只是想“这个游戏包含50张不确定的卡片”。你必须像个游戏设计师那样真正地去设计游戏!

纸上原型的缺陷

纸上原型存在一些你必须意识到的缺陷:

不能应对以敏捷或时间为基础的系统……虽然我们知道有许多以敏捷为基础的非数字化的游戏。想一想《街霸》系列电子游戏和James Ernest的实时卡片战争游戏《Brawl》之间的 相似和差异。有些能在纸上模拟得很好,有些就不同了。

street-fighter-4(from yuwings.org)

有些信息对玩家隐藏,但仍需要记录在案,如在RTS游戏中非常流行的“战争之雾”机制。另外,注意,这个有时候也是能解决的——经典儿童《战舰》游戏也有仿“战争之雾”机 制的,桌面游戏《Clue》也有信息对所有玩家隐藏。

极端复杂的算法要在纸上完成就太沉闷了,那种系统还是丢给Excel这种软件去制作“原型”吧。如果复杂的系统是游戏的必须及核心部分,这意味着“电脑玩得比玩家还开心”( 引用Sid Meier之语),也许有必要对游戏进行简化处理了。

“华而不实”等高质量的美术和动画显然不能靠简笔画和手写卡就给原型化。而且,这些也不是游戏机制的一部分。发果你的游戏更依赖视觉效果而不是系统,这意味着你不是一 个合格的系统设计师。

纸上原型不适用于测试电子游戏的UI。计算机UI是动态的,但纸是静态的。你可以从纸上草稿看出一点视觉设计的意思,但要知道电脑上的实际效果如何,你需要制作数字化原型 。

如你所见,纸上原型的优势是很普遍的,而其缺点却是特定的,所以每个设计师都应该掌握纸上原型的技巧,无论他们是制作电子游戏还是桌面游戏。

非数码设计师的原型工具

以下是我个人觉得很有用的原型制作材料。当然其他设计师可能也有自己最喜欢的材料,所以不可避免有人会对我的清单有异议。

各个品种的纸:白纸、线条纸和网格纸。这些特别适合一般的笔记和速成游戏面板或其他表面。

彩色画笔和铅笔。显然你需要一些能涂写的东西。颜色可以很好地区分各个游戏元素,或注释游戏组件。

索引卡片(3*5)。这些用来制作卡片,很适合混合。你可以把卡片对半开也可以三等分,做成不同大小的卡片。你也可以只是在卡片上写下想法,然后贴到墙上,便于你边看边整 理思路。这些纸片通用又便宜。

剪刀和胶带。这些是用来剪东西和粘东西的,对设计师的重要性,好比WD-40润滑油和管道胶带对水管工的重要性。

曲别针和/或长尾夹。这些可以把相关的材料固定在一起。例如,如果你做了好几份卡片,用这些曲别针或长尾夹就可以把相关的纸片夹在一起,不会和不同类的混起来(更惨的是 和不同的原型卡片混起来)。

不同颜色的玻璃珠。这些可以作标志物、计数器和游戏部件。

各种类型的骰子(4、6、8、12和20边的)。各个型号的都准备几个,颜色要不同。这些用来产生独立随机数。注意,骰子也可以当作游戏的部件,比如代表“石头”,数字是几就 代表有多少值——如6面骰子代表一个有6点攻击力的战士。

一小袋不值钱的硬币(请原谅我不知道其他国家的硬币面值是多少)。硬币可以作标记,可以产生随机变量,因为有两面,所以可以代表两种状态(游戏邦注:如各代表两个控制 硬币的玩家)。另外,硬币比骰子和玻璃珠更好堆放。

便利贴(from 3lian)

有色便利贴(小圆不干胶贴)。你可以把这些贴在石头、骰子或硬币作标记、装饰。你可以在上面记录必要的信息。

一本专门用来记录原型和测试的笔记本。这个东西要保存好,切不可丢失!

以上物品哪里找?这个要看你住在什么地方。除了骰子、玻璃珠和硬币,大多数东西可在办公用品店里找到。找硬币,请往银行走;骰子,一般的玩具店或漫画书店有售或网上购 买;玻璃珠,玩具店里可能有卖,不过通常是当作装饰品或工艺品。很多游戏套装里有玻璃珠,如果你能找到一款带玻璃珠的游戏,那就便宜了。

工艺品店和玩具店,无论是零售店还是网店,都可以给游戏设计师带来不错的灵感谢。我曾发现大量没上漆色的木质小方块(真是极佳的标记物和自定义骰子)和木质盘(质感好 ,比硬币大)。有次,我找到一套木质小方片,大约有1英寸,还有一些木质胡萝卜;我不知道我拿这些东西做什么,但总有一天会派上用场吧。我还发现有店面出售木质小人和各 种尺寸的铺砖。这些东西可能一时半会儿用不上,但项目开发到后期,肯定会有用。

你的第一个纸上原型

以下是一款经典儿童战争游戏的规则:

玩家:2

目标:先于对方打沉对方舰队的5艘潜艇。

设置:双方玩家各有一个10*10的网格面板,各行标有从1到10的数字,名列标有A到J的字母。玩家各有5艘潜艇:2个方格长的一艘,3个方格长的二艘,4个方格长的一艘,5个方格 长的一艘。玩家将自己的潜艇暗藏在自己的网格下,各艘潜艇可上下左右移动。一名玩家先移动。

游戏过程:轮到顺序的玩家叫一个方格的坐标(如B5或H10)。如果该坐标上没有任何敌方的潜艇占领,那么敌方玩家就说“没中”;否则,就说“命中”。另外,如果该方格被“ 命中”且该方格上的潜艇的所有“舱位”(即潜艇的方格长)都被击中,则该潜艇“沉没”,敌方玩家必须告诉对方哪只潜艇“沉没”。无论是否命中,叫方格的顺序轮给另一方 。

结果:当一名玩家击沉对方的所有潜艇,即获胜。玩具店一般有卖这个游戏套装,里面配有带塑料钉子的游戏面板。有些比较贵的电子版可以发出声音,但需要装电池。我觉得你 应该可以在5分钟内就完成该游戏的纸上原型。

只要在纸上画一个10*10的网格两张(一张记录你的潜艇分布情况,另一张记录攻击结果),就可以开始玩这个游戏了,体验与“现实”版相差无几。

现在,我们来干点脑力活:将这场“海战”当成游戏进行严格地分析。这个游戏的设计缺陷是什么?如何改进游戏规则?然后再想想:如何改良你的纸上原型,用来测试新游戏规 则?这个是很琐碎的事。以下是我个人提出来的改进方案:

如果潜艇未被攻击,那么玩家可以移动自己的潜艇。(修改原型:玩家可以把网格上原来的潜艇擦掉重画到其他位。)

允许玩家在自己的回合中不发动“攻击”,而是使用“声纳扫描”:可以叫任何一块3*3大小的区域,玩家说出该区域有潜艇占领的方格数字(0~9)。(这个地方就没什么好调整 的,直接按新规则玩就是了。)

如果玩家在这个回合中“命中”,则回合不变,仍然由该玩家“叫号”。(还是没有调整的必要,直接按新规则玩。)

采用不同形状的潜艇:除了直线形的,还可以有T形、方形等,就像俄罗斯方块一样。(调整原型,只需要把潜艇画成不同的形状即可。)

给双方玩家一个攻击的有效区域,如在炮弹在某个3*3的区域内可以获击所有敌方潜艇。玩家可以在自己的回合内使用,以代替普通攻击,但整个游戏玩家只能使用一次。(不修改 原型,按新规则玩。)

缩小游戏面板,把10*10的方格改成6*6的。(再画两个网格。)

如你所见,修改纸上模型真是又快又简单,想怎么改就怎么改。不要害怕你的想法“不靠谱”,不靠谱就不靠谱吧。即使是有经验的设计师第一次设计出来的东西也会“很糟”。 但是,除非你开始制作,则否永远也出不了好游戏。纸上原型就是一个理想的开端。

即时系统的原型制作

像《战舰》这种回合制的游戏,非数码的原型基本上够用了。那么如果是FPS类的电子游戏,如《光晕》,怎么办呢?纸上原型有办法模拟那种基本上围绕着即时射击的游戏吗?答 案是,完全可以。以下是揭示:

一个桌面游戏的“回合”相当于即时游戏中一定量的时间(如3秒)。

对于需要准确计时的躲避和命中系统,玩家成功与否取决于当前的难度和玩家的技能。这可以用随机死亡率来模拟。注意,即使电子游戏的系统不全是随机的,但从敌方玩家的角 度看,也等同于随机了:如果我向你开枪,无论你能不能躲开,我都无法掌控。

许多即时游戏使用的是3D地图,不能细分成一块一块的“空间”。不过这不妨碍你用桌面游戏的方式模拟。

例如,考虑以下原则:

玩家:2~6,自由参与

目标:命中敌方

设置:玩家从游戏面板上的某一个设计好的起点开始。面板被划分为六边形。各名玩家正对着六个方向中的一边。各名玩家均持有以下卡片:移动、转向、移动/转向、开枪。

游戏过程:每一回合,所有玩家选择一张自己的卡片,写有动作的那一面朝下。所有玩家同时揭开卡片。首先,选择“移动”的玩家可向任意方向移动2格,但不可以转向且必须继 续面朝一开始所选择的方向。然后,选择“移动/转向”的玩家可以移动1格,并顺/逆时针转向60度。最后,选择“开枪‘的玩家可以立刻杀死他们可以“看到”的敌方玩家。被杀死的玩家将淘汰出局。一个回合后,玩家再次从四张卡片中选择下一步行动的卡片。

结果:坚持到最后的玩家得胜。如果在同一回合中,二名或以上的玩家同时杀死对方,则游戏为平局。

现在我们加入新的规则:你只需随便地画一个六边形地图,添加几个六边形代表障碍物,玩家不可走过也不可射穿。

如果你确实去模拟这个游戏了,你会马上发玩有问题。比如,我没有定义什么叫“可以看到”,所以没有办法判定一枪打出去,到底是打中没中。你必须自己明确地定义这一点( 可能是直线正对的玩家为“可见”,或者在一定的范围以内等等)。你可能也注意到了,游戏的深度不够,没有重刷、能量源、弹药、命值补给、特殊武器等。这个游戏也不支持 “占山为王”之类的模式。以上所提到的东西都可以添加进去,只是再费几分钟的事。

这种原型有什么用呢?你可以用来测试提交上来的关卡设计方案,这样就可以在入进关卡编辑工具的执行以前就知道可行不可行了。如果你增加怪物和组队模式进去,再设计一个 限制弹药和命值的机制,你可以用怪物的数量来平衡弹药及命值,从而获得一个比较可观的游戏挑战。如果你增加了具有不同射程、杀伤力和命中率的武器种类,那么在给定的地 图上,你可以好好琢磨该使用哪款武器。将游戏改成电子版后,你还是必须重新审视这些设定,因为从一种媒体转换到另一种媒体上,转换率未必是100%……但毕竟开头做好了, 再理解游戏的机制及其作用方式就不难了。

即使这个电子版游戏不太成功,至少你和朋友还能在这个游戏上找点乐子。

我举这个例子是希望大家明白,大多数的电子游戏至少有那么几个部分是可以在纸上完成原型制作的。当然,不通过数字渠道发行的游戏也可以这么模拟。有些出自桌面RPG和LARP 游戏的系统在开发早期也可以用这种方式模拟。

关于网格

制作游戏面板的方法有很多,但这里有三条普遍的原则:将面板细分成方形网格。方格更容易操作,也更为玩家所熟悉,这样休闲玩家也容易上手。对于包含许多障碍物和移动挑 战的网格,方格更容易表示“此路不通”:不可通过的方格迫使玩家改变自己原来的路线而走其他路线。方格的缺点在于,对角线移动成问题:对角线移动是算作一格还是两格? 一格的话感觉太少了,两格的话感觉太多了。(对角线距离的真实数值是“根号2”,或约等于1.4……不过,计算这个显然没什么实在意义。)

将面板细分成六边形网格。六边形具有一些理想的数学功能,因为3个六边形的距离是固定的,无论你往哪个方向走——不会遇到方形网格的“对角线移动”问题。六边形网格的缺 点在于,玩家更容易躲开障碍物,所以移动受限的情况也少了很多。这到底好不好,得看游戏的属性。另外,六边形相当令人讨厌,很可能不会吸引那些没有经验的玩家。在空地上模拟,不要用游戏面板。每个回合,游戏物品的移动距离都用卷尺测量出固定的某某厘米。这样就更流畅更精确了,不过,六边形地图的某些缺点还是存在,并且很难说 玩的过程中玩家会不会一不小心就撞上桌子或把游戏物品给挪动了一点。

增加功能还是保持简单?

正如前面所述,我们的FPS游戏原型还需要其他功能特点,如生命值和弹药。为什么不直接从这些已经想到的额外系统开始,而是从简单的核心系统开始?我们首先从简单的核心规 则开始,然后再慢慢增加规则,而不是一次性完成整个游戏的设计,这么做有以下几个原因:

如果基本的核心规则不管用,添加额外的规则也保证核心规则生效。首先要把基本的规则做好了,才能添加复杂的东西。

如果你在不牢靠的基础上构建额外的规则,真正潜在的问题反而模糊了!有些东西看起来错了,但如果游戏中的其他系统、资源和对象太多了,你遇到的问题是因为核心机制出错 ,还是某种资源不平衡,或是地图的设计有误,还是其他什么问题,真的很难断定了。

在游戏的早期阶段,能简单就简单。当你想添加任何规则、机制、物品或资源时,你得问自己:确实有必要现在就加吗?此时,让你的懒惰掩盖你的创意吧。要在设计中加点什么 太容易了,但要拿掉什么东西却未必,所以只要游戏能玩,尽可能少增加其他东西。

如果你觉得选择起来有困难,那么就写一份你希望运用于游戏的想法清单,然后根据没有此物游戏是否可运作为标准,尽可能地划掉清单上的想法,直到你完全没办法再划为止。

你还可以找那些跟你在个人事务或情绪上没有利害关系的设计师作评判,让他们说说你的哪个想法是垃圾。更甚,你可以跟你的同事交换自己的原型,你看我的,我看你的!

更进一步

一旦你完成了可运作的核心玩法,那么你就可以往其中添加新的功能特征了。此时,你会禁不住想把最初想到的所有东西一股脑地全丢进去。忍住啊,别冲动。你每增加一个功能 特征,就要测试一次,直到确定新功能特征是有效的,或者发现新功能特征无效该丢弃。

为什么不一次性把所有东西加进去?因为你加进去的所有新东西都可能存在问题。如果你只增加了一个,一旦在测试中发现不对劲,你马上就知道问题出在哪里,因为你只改变过 一个东西。如果你一次就添加了十条规则,一旦出了错,要区分出哪条规则(或哪几条规则组合后)不适用就相当困难了。这跟编程序类似:如果你只写了一小块语句,然后进行 单元测试,很容易就知道漏洞所在,而如果你写了一万条语句才测试,出了问题的话……

是啊,确实是件沉闷的事。你必须测试,然后改变一条规则,然后再测试,再改变另一条规则,如此反复数十次(甚至上百次)。第一次测试很有趣,但你很快就会对一切都感到 厌烦。这是设计过程的一部分。有时候,游戏设计就是件苦差事,没什么乐趣可言。如果你想成为专业的设计师,你必需接受现实。记住专业设计师的目标:制作有趣的游戏,如 果游戏没意思,你就鼓起动力去改变和测试,直到达到你的目标。

要制作真正的游戏了,物质原型做完后的下一步就是制作文档。这些文档不必厚成500页的《游戏设计圣经》,只要记录你在反复设计、测试的过程中确定下来的规则和积累下来的 测试注意事项就够了。然后在开始项目以前,把这些文档格式化成其他人能读能理解的材料。同时,如果之后你忘了曾做过什么,这些材料也将成为有价值的参考资料——有时候,你不得不把一个创意暂时放到一边,个把月后你回头再考虑这个创意,我敢说你肯定已经忘记所有那些曾经刻骨铭心的细节,所以,制作记录文档非常有必要。

相关拓展阅读:篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

Level 1: Overview / What is a Game?

By Ian Schreiber

Welcome to Game Design Concepts! I am Ian Schreiber, and I will be your guide through this whole experiment. I’ve heard a lot of excitement throughout all of the registration process these last few months, and be assured that I am just as excited (and intimidated) at this whole process as anyone else. So let me say that I appreciate your time, and will do my best to make the time you spend on this worthwhile.

Course Announcements

Before we begin, I’d like to get a few quick administrative things out of the way:

* Registration. As I’m writing this, there is a large backlog of registrations sent in at the last minute. So, if you sent an email and have not yet received a reply, check your inbox in the next day or two. If you still haven’t received a response by Wednesday, it means I did not receive your email and you should find your previous one and forward it.

* On that subject, keep in mind there are over a thousand people actively participating here. I value all of your feedback and contributions, but if you send an email directly to me, understand that I may receive a lot and it may take some time to get back to you.

* I’ve set up two resources for this course, a wiki and a blog.

* The wiki is at http://gamedesignconcepts.pbworks.comand is intended for two things: as a resource for group collaboration (for those of you who are taking this course with friends), and as an area for people to post translations of this blog into other languages (as some of you have offered). If you think of other uses, feel free! Right now it is a closed wiki and requires an email address and password. If you registered, expect to receive an email in the next few days giving you login information.

* The discussion board is at http://gamedesignconcepts.aceboard.com and is the primary place for interactive discussion. I’ve created separate discussion areas by interest group (such as: an area for college students, another for professional educators, another for professional video game designers, and so on). I will create forums by geographic region soon, to allow you to find others in your area and arrange to meet in person, if you’d like. This is also where you’ll be able to post the work you do for this course, and give and receive peer review (these will become available as they are assigned). Lastly, there is a forum at the top called Meta Discussion, which is discussion for the course itself — what is working and what is not, in terms of using blog, wiki, forum and so on in order to communicate. You will have to create an account and then wait for the moderator to add you. This process may take a couple of days, so please be patient.

* If you twitter, use the tag #GDCU for any course-related tweets.

* If you have something to say about the course content itself, feel free to leave it as a comment here on this blog.

And with all of that out of the way, let’s talk about game design!

Course Overview

Most fields of study have been around for thousands of years. Game design has been studied for not much more than ten. We do not have a vast body of work to draw upon, compared to those in most other arts and sciences.

On the other hand, we are lucky. Within the past few years, we have finally reached what I see as a critical mass of conceptual writing, formal analysis, and theoretical and practical understanding to be able to fill a college curriculum… or at least, in this case, a ten-week course.

Okay, that isn’t entirely fair. There is actually a huge body of material in the field of game design, and many books (with more being released at an alarming rate). But the vast majority of it is either useless, or it is such dense reading that no one in the field bothers to read it. The readings we’ll have in this course are those that have, for whatever reason, pervaded the industry; many professional designers are already familiar with them.

This course will be divided, roughly, into two parts. The first half of the course will focus on the theories and concepts of game design. We will learn what a game is, how to break the concept of a game down into its component parts, and what makes one game better or worse than another. In the second half of the course, the main focus is the practical aspect of how to create a good game out of nothing, and the processes that are involved in creating your own games. Throughout all of the course, there will be a number of opportunities to make your own games (all non-digital, no computer programming required), so that you can see how the theory actually works in practice.

What is a game?

Those of you who have read a little into the Challenges text may think this is obvious. My preferred definition is a play activity with rules that involves conflict. But the question “what is a game?” is ctually more complicated than that:

* For one thing, that’s my definition. Sure, it was adopted by the IGDA Education SIG (mostly because no one argued with me about it). There are many other definitions that disagree with mine. Many of those other definitions were proposed by people with more game design experience than me. So, you can’t take this definition (or anything else) for granted, just because Ian Says So.

* For another, that definition tells us nothing about how to design games, so we’ll be talking about what a game is in terms of its component parts: rules, resources, actions, story, and so on. I call these things “formal elements” of games, for reasons that will be discussed later.

Also, it’s important to make distinctions between different games. Consider the game of Three to Fifteen. Most of you have probably never heard of or played this game. It has a very simple set of rules:

* Players: 2

* Objective: to collect a set of exactly three numbers that add up to 15.

* Setup: start by writing the numbers 1 through 9 on a sheet of paper. Choose a player to go first.

* Progression of Play: on your turn, choose a number that has not been chosen by either player. You now control that number. Cross it off the list of numbers, and write the number on your side of the paper to show that it is now yours.

* Resolution: if either player collects a set of exactly three numbers that add up to exactly 15, the game ends, and that player wins. If all nine numbers are collected and neither player has won, the game is a draw.

Go ahead and play this game, either against yourself or against another player. Do you recognize it now?

The numbers 1 through 9 can be arranged in a 3×3 grid known as a “magic square” where every row, column and diagonal adds up to exactly 15:

Now you may recognize it. It is the game of Tic-Tac-Toe (or Noughts and Crosses or several other names, depending on where you live). So, is Tic-Tac-Toe the same game as Three-to-Fifteen, or are they different games? (The answer is, it depends on what you mean… which is why it is important to define what a “game” is!)

Working towards a Critical Vocabulary

When I say “vocabulary” what I mean is, a set of words that allows us to talk about games. The word “critical” in this case does not mean that we are being critical (i.e. finding fault with a game), but rather that we are able to analyze games critically (as in, being able to analyze them carefully by considering all of their parts and how they fit together, and looking at both the good and the bad).

Vocabulary might not be as fascinating as that game you want to design with robot laser ninjas, but it is important, because it gives us the means to talk about games. Otherwise we’ll be stuck gesturing and grunting, and it becomes very hard to learn anything if we can’t communicate.

One of the most common ways to talk about games is to describe them in terms of other games. “It’s like Grand Theft Auto meets The Sims meets World of Warcraft.” But this has two limitations. First, if I haven’t played World of Warcraft, then I won’t know what you mean; it requires us to both have played the same games. Second, and more importantly, it does not cover the case of a game that is very different. How would you describe Katamari Damacy in terms of other games?

Another option, often chosen by those who write textbooks on game design, is to invent terminology as needed and then use it consistently within the text. I could do this, and we could at least communicate with each other about fundamental game design concepts. The problem here is what happens after this course is over; the jargon from this course would become useless when you were talking to anyone else. I cannot force or mandate that the game industry adopt my

terminology.

One might wonder, if having the words to discuss games is such an important thing, why hasn’t it been done already? Why hasn’t the game industry settled on a list of terms? The answer is that it is doing so, but it is a slow process. We’ll see plenty of this emerging in the readings, and it is a theme we will return to many times during the first half of this course.

Games and Play

There are many kinds of play: tossing a ball around, playing make-believe, and of course games. So, you can think of games as one type of play.

Games are made of many parts, including the rules, story, physical components, and so on. Play is just one aspect of games. Therefore, you can also think of play as one part of games.How can two things both be a subset the other? It seems like a paradox, and it’s something you are welcome to think about on your own. For our purposes, it doesn’t matter — the point here is that games and play are concepts that are related.

So, what is a game, anyway?

You might have noticed I never answered the earlier question of what a game is. This is because the concept is very difficult to define, at least in a way that doesn’t either leave things out that are obviously games (so the definition is too narrow), or accept things that are clearly not games (making the definition too broad)… or sometimes both.

Here are some definitions from various sources:

* A game has “ends and means”: an objective, an outcome, and a set of rules to get there. (David Parlett)

* A game is an activity involving player decisions, seeking objectives within a “limiting context” [i.e. rules]. (Clark C. Abt)

* A game has six properties: it is “free” (playing is optional and not obligatory), “separate” (fixed in space and time, in advance), has an uncertain outcome, is “unproductive” (in the sense of creating neither goods nor wealth — note that wagering transferswealth between players but does not create it), is governed by rules, and is “make believe” (accompanied by an awareness that the game is not Real Life, but is some kind of shared separate “reality ”). (Roger Callois)

* A game is a “voluntary effort to overcome unnecessary obstacles.” This is a favorite among my classroom students. It sounds a bit different, but includes a lot of concepts of former definitions: it is voluntary, it has goals and rules. The bit about “unnecessary obstacles” implies an inefficiency caused by the rules on purpose — for example, if the object of Tic Tac Toe is to get three symbols across, down or diagonally, the easiest way to do that is to simply write three symbols in a row on your first turn while keeping the paper away from your opponent. But you don’t do that, because the rules get in the way… and it is from those rules that the play emerges. (Bernard Suits)

* Games have four properties. They are a “closed, formal system” (this is a fancy way of saying that they have rules; “formal” in this case means that it can be defined, not that it involves wearing a suit and tie); they involve interaction; they involve conflict; and they offer safety… at least compared to what they represent (for example, American Football is certainly not what one would call perfectly safe — injuries are common — but as a game it is an abstract representation of warfare, and it is certainly more safe than being a soldier in the middle of combat). (Chris Crawford)

* Games are a “form of art in which the participants, termed Players, make decisions in order to manage resources through game tokens in the pursuit of a goal.” This definition includes a number of concepts not seen in earlier definitions: games are art, they involve decisions and resource management, and they have “tokens” (objects within the game). There is also the familiar concept of goals. (Greg Costikyan)

* Games are a “system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome” (“quantifiable” here just means, for example, that there is a concept of “winning” and “losing”). This definition is from the book Rules of Playby Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. That book also lists the other definitions given above, and I thank the authors for putting them all in one place for easy reference.

By examining these definitions, we now have a starting point for discussing games. Some of the elements mentioned that seem to be common to many (if not all) games include:

* Games are an activity.

* Games have rules.

* Games have conflict.

* Games have goals.

* Games involve decision making.

* Games are artificial, they are safe, and they are outside ordinary life. This is sometimes referred to as the players stepping into the “Magic Circle” or sharing a “lusory attitude”.

* Games involve no material gain on the part of the players.

* Games are voluntary. If you are held at gunpoint and forced into an activity that would normally be considered a game, some would say that it is no longer a game for you. (Something to think about: if you accept this, then an activity that is voluntary for some players and compulsory for others may or may not be a game… depending on whose point of view you are looking at.)

* Games have an uncertain outcome.

* Games are a representation or simulation of something real, but they are themselves make believe.

* Games are inefficient. The rules impose obstacles that prevent the player from reaching their goal through the most efficient means.

* Games have systems. Usually, it is a closed system, meaning that resources and information do not flow between the game and the outside world.* Games are a form of art.

Weaknesses of Definitions

Which of the earlier definitions is correct?

None of them are perfect. If you try to come up with your own definition, it will likely be imperfect as well. Here are a few common edge cases that commonly cause problems with definitions:

* Puzzles, such as crossword puzzles, Sudoku, Rubik’s Cube, or logic puzzles. Are these games? It depends on the definition. Salen & Zimmerman say they are a subset of games where there is a set of correct answers. Costikyan says they are not games, although they may be contained within a game.

* Role-playing games, such as Dungeons & Dragons. They have the word “game” right in the title, yet they are often not considered games (for example, because they often have no final outcome or resolution, no winning or losing).

* Choose-your-own-adventure books. These are not generally thought of as games; you say you are “reading” a book, not “playing” it. And yet, it fits most of the criteria for most definitions of a game. To make things even more confusing, if you take one of these books, add a tear-out “character sheet” with some numeric stats, include “skill checks” on some pages where you roll a die against a stat, and call it an “adventure module” instead of a “choose- your-own-adventure book,” we would now call it a game!

* Stories. Are games stories? On the one hand, most stories are linear, while games tend to be more dynamic. On the other hand, most games have some kind of story or narrative in them; we even have professional story writers that work on multi-million-dollar video game projects. And even beyond that, a player cantell a story about their game experience (“let me tell you about this Chess game I played last night, it was awesome”). For now, keep in mind that the concepts of story and game are related in many ways, and we’ll explore this more thoroughly later in the course.

Let’s Make a Game

You might be wondering how all of this is going to help you make games. It isn’t, directly… but we need to at least take some steps towards a shared vocabulary so that we can talk about games in a meaningful way.

Here’s a thing about games. I hear a lot from students that they’re afraid they won’t be able to make a game. They don’t have the creativity, or the skills, or whatever. This is nonsense, and it is time to get that out of our systems now.

If you have never made a game before, it is time to get over your fear. You are going to make a game now. Take out a pencil and paper (or load up a drawing program like Microsoft Paint). This will take all of 15 minutes and it will be fun and painless, I promise.

I mean it, get ready. Okay?

We are going to make what is referred to as a race-to-the-end board game. You have probably played a lot of these; the object is to get your token from one area of a game board to another. Common examples include Candyland, Chutes & Ladders, and Parcheesi. They are the easiest kind of game to design, and you’re going to make one now.

First, draw some kind of path. It can be straight or curved. All it takes is drawing a line. Now divide the path into spaces. You have now completed the first step out of four. See how easy this is?

Second, come up with a theme or objective. The players need to get from one end of the path to the other; why? You are either running towards something or running away from something. What are the players represented as in the game? What is their goal? In the design of many games, it is often helpful to start by asking what the objective is, and a lot of rules will fall into place just from that. You should be able to come up with something (even if it is extremely silly) in just a few minutes. You’re now half way done!

Third, you need a set of rules to allow the players to travel from space to space. How do you move? The simplest way, which you’re probably familiar with, is to roll a die on your turn and move that many spaces forward. You also need to decide exactly how the game ends: do you have to land on the final space by exact count, or does the game end as soon as a player reaches or passes it?

You now have something that has all the elements of a game, although it is missing one element common to many games: conflict. Games tend to be more interesting if you can affect your opponents, either by helping them or harming them. Think of ways to interact with your opponents. Does something happen when you land on the same space as them? Are there spaces you land on that let you do things to your opponents, such as move them forward or back? Can you

move your opponents through other means on your turn (such as if you roll a certain result on the die)? Add at least one way to modify the standing of your opponents when it is your turn.

Congratulations! You have now made a game. It may not be a particularly good game (as that is something we will cover later in this course), but it is a functional game that can be played, and you made it in just a few minutes, with no tools other than a simple pencil and paper.

Credit for developing this exercise goes to my friend and co-author, Brenda Brathwaite, who noticed that there is this invisible barrier between a lot of people and game design, and created this as a way to get her students over their initial fear that they might not be able to design anything.

Lessons Learned

If you take away nothing else from this little activity, realize that you can have a playable game in minutes. It does not take programming skill. It does not require a great deal of creativity. It does not require lots of money, resources, or special materials. It does not take months or years of time. Making a good game may require some or all of these things, but the process of just starting out with a simple idea is something that can be done in a very short period of time with nothing more than a few slips of paper.

Remember this as we move forward in this course. When we talk about iteration and rapid prototyping, many people are afraid to commit to a design, to actually build their idea. They are afraid it will take too long, or that the idea will not turn out to be as good as it seems in their head. Part of the process involves killing weak ideas and making them stronger, by actually making and playing your game. The faster you can have something up and running, and the more times that you can play it, the better a game you can make. If it takes you more than a few minutes to make your first prototype of a new idea, it is taking too long.

Homeplay

Some classes assign “homework problems.” I’m not sure what is less fun: the concept of work at home, or having problems. So, I call everything a “homeplay” because I want these to be fun and interesting.

Before this Thursday, read the following:

* Challenges for Game Designers, Chapter 1 (Basics). This is just a short introduction to the text.

* I Have No Words and I Must Design, by Greg Costikyan. To me (and I’m sure others will disagree), this essay is the turning point when game design started to become its own field of study. Since it all started here, for me at least, I think it only fitting to introduce it at the start of this course. (There is a newer version here[PDF] if you are interested, but I prefer the original for its historical importance.)

* Understanding Games 1, Understanding Games 2, Understanding Games 3, Understanding Games 4. These are not readings, but playings. They are a series of short Flash games that attempt to explain some basic concepts of games in the form of a game. The name is a reference to Understanding Comics, a comic book that explains about comic books. Each one takes about five minutes.

Last time we asked the question: what is a game? Today, we look into a related question: what, exactly, is game design? Last time, we made a simple game. This time, we will look into the process of how games are made in general. While it is possible to make a race-to-the-end board game in 15 minutes, you will need to take a little longer if you are looking to make the next Settlers of Catan or World of Warcraft.

Course Announcements

Some administrative things that have come up since Monday:

? First, I would like to apologize to those who are registered for the misbehavior of the wiki. It was sending out hourly announcements of updates… and there were a lot of updates! I have attempted to turn off these updates, so you should hopefully not receive any more “wiki-spam” but if you do, you can shut it off manually by going to your own settings and changing notifications to “Never.”

? As of 5am GMT this morning, the discussion forums are set up and operational. I look forward to seeing some really great discussion. There were quite a few spambots that tried to register, so I had to check every forum account against course registrations. If you got an email that your account was rejected, it just means I was unable to match it up to a course registration; please try again. If you have not yet created a forum account, you can make it easiest

for me by using the same email on the forums that you used to register for this course… and if you’re unwilling to do that, at least put some kind of identifying information in there (like your name and location) so I can find you in the list. Thank you.

? Lastly, to those of you who sent in a registration email after the course started (that is, if your email was timestamped after Monday, noon GMT), I apologize for not being able to add you after the fact. Registration emails have taken a lot of my time prior to the start of the course, and if I accept late registrations I will not have the time to do other things for the course. Whether you are registered or not, this blog is free and open to the public (as is the Twitter feed), and I hope you do still follow along and get a lot out of the experience.

Game Design

We will use the word “design” a lot in this course, and unfortunately it is a term that is a bit overused, so I will clarify what I mean here. As it says in Challenges, game design is the creation of the rules and content of a game. It does not involve programming, art or animation, or marketing, or any of the other myriad tasks required to make a game. All of these tasks collectively can be called “game development” and game design is one part of development.

Unfortunately, I have seen the term “design” used (particularly in some college curricula) to refer to all aspects of development. When used in the video game industry (or the board game industry), “game design” has a very specific meaning, and that is the meaning that we will use for this course.

Multiple Types of Game Design

As mentioned in Challenges, there are many tasks associated with game design: system design, level design, content design, user interface design, world building, and story writing You could fill several 10-week courses with any one of these, so this summer course will not be a full treatment of the entire range of game design. We will touch lightly on UI, story writing and content when relevant, but the majority of this course focuses on system design (also sometimes called “systems design” or “core systems design”).

System design is about defining the basic rules of the game. What are the pieces? What can you control? What actions can you take on your turn (if there are “turns” at all)? What happens when you take each action, and how does it affect the game state? In general, system design is the creation of three things:

? Rules for setup. How does the game begin?

? Rules for progression of play. Once the game begins, what can the players do, and what happens when they do things?

? Rules for resolution. What, if anything, causes the game to end? If the game has an outcome (such as winning or losing), how is that outcome determined?

If you look back at Three-to-Fifteen from Monday, you’ll notice those very simple rules contain all of these parts. The creation of those rules is system design, and that is what we will be spending most of our time with over this summer.

What is a Game Designer?

As you may have noticed, game design is an incredibly broad field. Those of us who are professional designers sometimes have trouble explaining what we do to our families and friends. Part of the reason for this is that we do so many things. Here are some analogies I’ve seen when trying to explain what it is like to be a game designer:

? Game designers are artists. The term “art” is just as difficult to define as the word “game”… but if games can be a form of art (as we saw in Costikyan’s definition, at least), then designers would be artists.

? Game designers are architects. Architects do not build physical structures; they create blueprints. Video game designers also create “blueprints” which are referred to as “design docs.” Board game designers create “blueprints” as well — in the form of prototypes — which are then mass-produced by publishers.

? Game designers are party hosts. As designers, we invite players into our space and try our best to show them a good time.

? Game designers are research scientists. As I will touch on later today, we create games in a manner that is very close to the scientific method.

? Game designers are gods. We create worlds, and we create the physical rules that govern those worlds.

? Game designers are lawyers. We create a set of rules that others must follow.

? Game designers are educators. As we will see later when we start reading Theory of Fun, entertainment and education are strongly linked, and games are (at least sometimes) fun because they involve learning new skills.

If game design is all these things, where would it fit in a college curriculum? It could be justified in the school of education, or art, or architecture, or theology, or recreation management, or law, or engineering, or applied sciences, or half a dozen other things.

Is a game designer all of these things? None of them? It is open for discussion, but I think that game design has elements of many other fields, but it is still its own field. And you can see just how broad the field is! As the field of game design advances, we may see a day where game designers are so specialized that “game design” will be like the field of “science” — students will need to pick a specialty (Chemistry, Biology, Physics, etc.) rather than just “majoring in Science.”

Speaking of Science…

How is a game designed? There are many methods.

Historically, the first design methodology was known as the waterfall method: first you design the entire game on paper, then you implement it (using programming in a video game, or creating the board and pieces for a non-digital game), then you test it to make sure the rules work properly, add some graphical polish to make it look nice, and then you ship it.

Waterfall is so named because, like water in a waterfall, you can only move in one direction. If you’re busy making the final art for the game and it occurs to you that one of the rules needs to change, too bad — the methodology does not include a way to go back to the design step once you are done.

At some point, someone figured out that it might be a good idea to at least have the option of going back and fixing things in earlier steps, and created what is sometimes known as the iterative approach. As with waterfall, you first design the game, then implement it, and then make sure it works. But after this you add an extra step of evaluating the game. Play it, decide what is good and what needs to change. And then, make a decision: are you done, or should you go back to the design step and make some changes? If you decide the game is good enough, then that is that. But if you identify some changes, you now go back to the design step, find ways to address the identified problems, implement those changes, and then evaluate again. Continue doing this until the game is ready.

If this sounds familiar, it is because this is more or less the Scientific Method:

1. Make an observation. (“My experience in playing/making games has shown me that certain types of mechanics are fun.”)

2. Make a hypothesis. (“I think that this particular set of rules I am writing will make a fun game.”)

3. Create an experiment to prove or disprove the hypothesis. (“Let’s organize a playtest of this game and see if it is fun or not.”)

4. Perform the experiment. (“Let’s play!”)

5. Interpret the results of the experiment, forming a new set of observations. Go back to the first step.

With non-digital (card and board) games, this process works fine, because it can be done quickly. With video games, there is still one problem:

implementation (i.e. programming and debugging) is expensive and takes a long time. If it takes 18 months to code the game the first time and you only have two years, you will not get a lot of time to playtest and modify the game.

In general, the more times you iterate, the better your final game will be.

Therefore, any game design process should involve iterating (that is, going through an entire cycle of designing, implementing and evaluating) as much as possible, and anything you can do that lets you iterate faster will usually lead to a better game in the end. Because of this, video game designers will often prototype on paper first, and then only get the programmers involved when they are confident that the core rules are fun. We call this rapid prototyping.

Iteration and Risk

Games have many kinds of risk associated with them. There is design risk, the risk that the game will not be fun and people won’t like it. There is implementation risk, the possibility that the development team will not be able to build the game at all, even if the rules are solid. There is market risk, the chance that the game will be wonderful and no one will buy it anyway. And so on.The purpose of iteration is to lower design risk. The more times you iterate, the more you can be certain that the rules of your game are effective.

This all comes down to one important point: the greater the design risk of your game (that is, if your rules are untested and unproven), the more you need iteration. An iterative method is not as critical for games where the mechanics are largely lifted from another successful game; sequels and expansion sets to popular games are examples of situations where a Waterfall approach may work fine.

That said, most game designers have aspirations of making games that are new, creative, and innovative.

Why This Course is Non-Digital…

Some of you would rather make board games anyway, so you don’t care how video games are made. But for those of you who would love to make video games, you may have wondered why we will be spending so mch time making board and card games in this course. Now you know: it is because iteration is faster and cheaper with cardboard. Remember from Monday: you can make a board game in 15 minutes. Coding that game will take significantly longer. When possible,

prototype on paper first, because a 15-minute paper prototype and an hour-long playtest session can save you months of programming work.

Later in this course, we will discuss in detail methods of paper prototyping, both for traditional board games and also for various types of video games.

There is another reason why we will concentrate primarily on non-digital games this summer, particularly board and card games. This is a course in systems design, that is, creating the rules of the game. In board games, the rules are laid bare. There may be some physical components, sure, but the play experience is almost entirely determined by the rules and the player interactions. If the rules are not compelling, the game will not be fun, so working in this medium makes a clear connection between the rules and the player experience.

This is not as true in video games. Many video games have impressive technology (such as realistic physics engines) and graphics and sound, which can obscure the fact that the gameplay is stale. Video games also take much longer to make (due to programming and art/audio asset creation), making them an impractical choice for a ten-week course.

The connection between rules and player experience is also muddied in tabletop role-playing games. I realize that many of you have expressed an interest primarily in RPG design, so this may seem strange to you. However, keep in mind that an RPG is essentially a collaborative story-telling exercise (with a rules system in place to set boundaries for what can and can’t happen). As such, a wonderful system can be ruined by players who have poor story-telling and improv skills, and a weak system can be salvaged by skillful players. As such, we will stay away from these game genres, at least in the early stages.

Trying it out

Take that 15-minute game you made last time, and play it, if you haven’t already. As you are playing, ask yourself: is this more fun or less fun than playing your favorite published games? Why? What could you change about your game to make it better? You do not have to play the game to completion, but only for as long as it takes you to get the overall feeling of what it is like to play.Then, after playing once, make at least one change. Maybe you’ll change the rules for movement, or add a new way for players to interact. Maybe you’ll change some of the spaces on the board.

Whatever you do, for whatever reason, make a change and then play again. Note the differences. Has the change made the game better, or worse? Has this one change made you think of additional changes you could make? If the game got worse, would you just change the rule back, or would you change it again in a different way?

We will be looking at the playtest process in detail later in this course. For now, I just want everyone to get over that fear: “what if I play my game and it sucks?” With the game you designed on Monday, the odds are very high that your game does suck (seriously, did you expect to make the next Gears of War in 15 minutes?). This does not make you a “bad designer” by any means — but it should make it clear that the more time you put into a game and the more iterations you make, the better it gets.

Lessons Learned

The one big takeaway from today is that the more you iterate on a game, the better it becomes. Great designers do not design great games. They usually design really bad games, and then they iterate on them until the games become great.

This has two corollaries:

? You want to have a playable prototype of your game as early in development as possible. The faster you can playtest your ideas, the more time you have to make changes.

? Given equal amounts of time, a shorter, simpler game will give a better experience than a longer, complicated game. A game that takes ten hours to play to completion will give you fewer iterations than a game that can be played in five minutes. When we start on the Design Project later in this course, keep this in mind.

Homeplay

Before next Monday, read the following. I will be referencing these in Monday’s content when we talk about the formal elements of games:

? Challenges for Game Designers, Chapter 2 (Atoms). This will act as a bridge between last Monday when we talked about a critical vocabulary, and next Monday when we will start breaking down the concept of a “game” into its component parts.

? Formal Abstract Design Tools, by Doug Church. This article builds on Costikyan’s I Have No Words, offering some additional tools by which we can analyze and design games. While he does use many examples from video games, think about how the core concepts in the article can apply to other kinds of games as well.

Today marks the last day that we continue in building a critical vocabulary from which to discuss games; this Thursday we will dive right in to the game design process. Today I want the last pieces to fall into place: we need a way to dissect and analyze a game by discussing its component parts and how they all fit together. This can be useful when discussing other people’s games (it would be nice if, for example, more professional game reviews could do this properly), but it is also useful in designing our own games. After all, how can you design a game if you don’t know how all the different parts fit together?

Course Announcements

As usual, there are a few things I’d like to announce and clarify:

I’m happy to announce that the course wiki is now open to the public (read-only access). This wiki is pretty much entirely run by the participants who registered for this course. Among other things, the blog posts here have already been translated into five different languages. I am impressed and humbled at the level of participation going on there, and encourage casual viewers to stop by and check it out.

I noticed some confusion on this so I would like to clarify: for readings in the Challenges text, you do not have to actually do all of the challenges at the end of the chapter. You certainly can if you want, but most chapters have five long challenges and ten short ones, and I would call that an extreme workload for a class of this pace. Repeat, you do not have to do all of the challenges (except where expressly noted on this blog).

A note on the reading for today

One of the readings for today was Doug Church’s Formal Abstract Design Tools. I want to mention a few things about this. First, he mentions three aspects of games that are worth putting in our design toolbox:

Player intention is defined as the ability of the player to devise and carry out their own plans and goals. We will come back to this later on in this course, but for now just realize that it can be important in many games to allow the player to form a plan of action.

Perceivable consequence is defined in the reading as a clear reaction of the game to the player’s actions. Clarity is important here: if the game reacts but you don’t know how the game state has changed, then you may have difficulty linking your actions to the consequences of those actions. I’ll point out that “perceivable consequence” is known by a more common name: feedback.

Story is the narrative thread of the game. Note that a game can contain two different types of story: the “embedded” story (created by the designer) and the “emergent” story (created by players). Emergent story happens, for example, when you tell your friends about a recent game you played and what happened to you during the play: “I had taken over all of Africa, but I just couldn’t keep the Blue player out of Zaire.” Embedded story is what we normally think of as the “narrative” of the game: “You are playing a brave knight venturing into the castle of an evil wizard.” Doug’s point is that embedded story competes with intention and consequence — that is, the more the game is “on rails”, the less the player can affect the outcome. When Costikyan said in “I Have No Words” that games are not stories, Doug provides what I think is a better way of saying what Costikyan meant.

Here is an example of why player intention and perceivable consequence are important. Consider this situation: you are playing a first-person shooter game. You walk up to a wall that has a switch on it. You flip the switch. Nothing happens. Well, actually something did happen, but the game gives you no indication of what happened. Maybe a door somewhere else in the level opened. Maybe you just unleashed a bunch of monsters into the area, and you’ll run into them as soon as you exit the current room. Maybe there are a series of switches, and they all have to be in exactly the right pattern of on and off (or they have to be triggered in the right order) in order to open up the path to the level exit. But you have no way of knowing, and so you feel frustrated that you must now do a thorough search of everywhere you’ve already been… just to see if the switch did anything.

How could you fix this? Add better feedback. One way would be to provide a map to the player, and show them a location on the map when the switch was pulled. Or, show a brief cut scene that shows a door opening somewhere. I’m sure you can think of other methods as well.

On another subject, Doug also included an interesting note at the end of the article about how he values beta testing, and half of his readers found the first two pages slow, so start at page 3 if you’re in that half. This would be an example of iteration in the design of this essay, of exactly the sort we talked about.

Now, I’m sure this note was partly in jest, but let’s take it at face value. There’s a slight problem with this fix: you don’t see the note until you’ve already read all of the way through the article, and it’s too late to do anything about it. If Doug were to iterate on his design a second time, what would you suggest he do? (I’ve heard many suggestions from my students in the past.)

Qualities of Games

It was rightly pointed out in the comments of this blog that on the first day of this course, I contradicted myself: I insisted that a critical vocabulary was important, and then I went on to say that completely defining the word “game” is impossible. Let’s reconcile this apparent paradox.

Take a quick look at the definitions listed on the first day. Separate out all of the qualities listed from each definition that may apply to games. We see some recurring themes: games have rules, conflict, goals, decision-making, and an uncertain outcome. Games are activities, they are artificial / safe / outside ordinary life, they are voluntary, they contain elements of make-believe / representation / simulation, they are inefficient, they are art, and they are closed systems. Think for a moment about what other things are common to all (or most) games. This provides a starting point for us to identify

individual game elements.I refer to these as “formal elements” again, not because they have anything to do with wearing a suit and tie, but because they are “formal” in the mathematical and scientific sense: something that can be explicitly defined. Challenges refers to them as “atoms” — in the sense that these are the smallest parts of a game that can be isolated and studied individually.

What are atomic elements of games?

This depends on who you ask. I have seen several schemes of classification. Like the definition of “game,” none is perfect, but by looking at all of them we can see some emerging themes that can shed light on the kinds of things that we need to create as game designers if we are to make games.

What follows are some parts of games, and some of the things designers may consider when looking at these atoms.

Players

How many players does the game support? Must it be an exact number (4 players only), or a variable number (2 to 5 players)? Can players enter or leave during play? How does this affect play?

What is the relationship between players: are there teams, or individuals? Can teams be uneven? Here are some example player structures; this is by no means a complete list:

Solitaire (1 player vs. the game system). Examples include the card game Klondike (sometimes just called “Solitaire”) and the video game Minesweeper.

Head-to-head (1 player vs. 1 player). Chess and Go are classic examples.

“PvE” (multiple players vs. the game system). This is common in MMOs like World of Warcraft. Some purely-cooperative board games exist too, such as Knizia ’s Lord of the Rings, Arkham Horror, and Pandemic.

One-against-many (1 player vs. multiple players). The board game Scotland Yard is a great example of this; it pits a single player as Mr. X against a team of detectives.

Free-for-all (1 player vs. 1 player vs. 1 player vs. …). Perhaps the most common player structure for multi-player games, this can be found everywhere, from board games like Monopoly to “multiplayer deathmatch” play in most first-person shooter video games.

Separate individuals against the system (1 player vs. a series of other players). The casino game Blackjack is an example, where the “House” is playing as a single player against several other players, but those other players are not affecting each other much and do not really help or hinder or play against each other.

Team competition (multiple players vs. multiple players [vs. multiple players...]). This is also a common structure, finding its way into most team sports, card games like Bridge and Spades, team-based online games like “Capture the Flag” modes from first-person shooters, and numerous other games.

Predator-Prey. Players form a (real or virtual) circle. Everyone’s goal is to attack the player on their left, and defend themselves from the player on their right. The college game Assassination and the trading-card game Vampire: the Eternal Struggle both use this structure.

Five-pointed Star. I first saw this in a five-player Magic: the Gathering variant. The goal is to eliminate both of the players who are not on either side of you.

Objectives (goals)

What is the object of the game? What are the players trying to do? This is often one of the first things you can ask yourself when designing a game, if you’ re stuck and don’t know where to begin. Once you know the objective, many of the other formal elements will seem to define themselves for you. Some common objectives (again, this is not a complete list):

Capture/destroy. Eliminate all of your opponent’s pieces from the game. Chess and Stratego are some well-known examples where you must eliminate the opposing forces to win.

Territorial control. The focus is not necessarily on destroying the opponent, but on controlling certain areas of the board. RISK and Diplomacy are examples.