如何面对具有内在抽象性的游戏玩法

作者:Chris DeLeon

弹球戏兼电子游戏设计师George Gomez在接受访问时解释了弹球戏游戏玩法虽然具有抽象性,但作为设计师的他一直在努力使用基于主题的游戏玩法理念去减少这类型游戏的抽象。玩家将使用磁铁切换杆的位置以敲击木头周围的铁球,但是当人们看到这类型游戏时,他们的思想却被赛车,卡通角色,科幻主题,授权电影元素或其它艺术装饰元素所控制。在20世纪90年代早中期,弹球戏设计师有时候会添加一些游戏领域元素或相联系的目标到主题中,并以此尝试着减少游戏的抽象(就像Steve Ritchie的《High Speed》:推动信号灯从绿色变成黄色再变成红色,然后运行红灯,然后“逃离”警察,但这只是关于一颗球四处滚动而已)。

比起电子游戏,弹球戏是一种更严格的表达媒介,因为它是依赖于廉价,可靠的物理机制而不是电子游戏中的动画图像和潜在游戏玩法。

因为常常编写有关电子游戏的内容,所以在此我并未考虑到计算机游戏是由桌面游戏(游戏邦注:基于回合制,网格或受菜单驱动的策略)所进化而来,这可能比抽象内容更容易被理解。而我所强调的似乎是那些玩家可以奔跑,跳跃,收集事物,射击,打开并实时与空间环境进行互动的文字和情境化游戏。

玩家并未跳跃,玩家角色也未跳跃,存在一些我们通过关于跳跃的比喻所推断出的内容。表面之下所发生的事比跳跃更加复杂且反常,然而在表面上我们看到的却只是像跳跃这般简单,甚至比跳跃更加自然的内容。

我并不想夸大这一例子,因为如果这么做我可能会开始反驳自己。来自2000年代中期的流行理念便是游戏玩法可以被当成是四处跳跃且互动的无意义矩形。当然了,如果我所看到的是一个忍者,一只青蛙或一艘太空船的话它便非常重要,这不仅仅是为了我们通过想象所获得的情境支持和期待。

对于这一点,我将在此再次指向弹球戏:基于任何特定桌面的一些得分活动主要是围绕着游戏的主题或比喻(游戏邦注:如“杀死巨龙”或“守护巴黎”),而剩下的只是一些抽象的内容(如“1000个点数”或“奖励倍增”)。在20世纪80年代早中期以前,并没有任何得分活动与游戏主题相关联。从某种程度上来说,美术仅仅只是关于毫不相干的抽象游戏的装饰,类似画在纸牌背部的图案一样,而在20世纪30年代,即当弹球戏开始兴起时,像纸牌背部这样抽象的模式开始频繁地出现在桌面上了。

尽管美术和游戏玩法之间具有很大的差别,但是当20世纪40年代以及50年代,产业开始将运动暗示和运动比喻推向其它主题的混合物时,游戏也开始描述战斗机,钓鱼,牛仔等等对象。虽然任何纸牌模式(除了最廉价的)都具有特别的新颖性,但是背部玻璃艺术和盒子贴花的区别在弹球戏主要游戏玩法大受欢迎的几十年间对于销售全新大型且昂贵的街机来说真的非常重要。

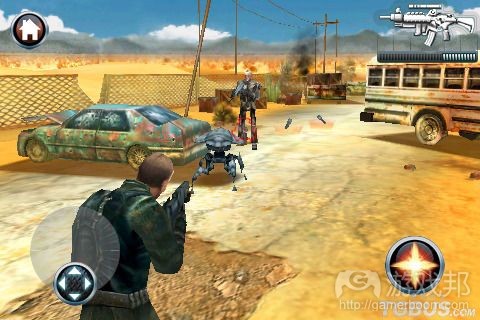

视觉效果推动着我们在玩游戏或思考游戏时发挥各种想象。这让我们在继续游戏时不会遗忘关联性。就像玩《终结者2》便是着眼于来自电影的插图和元素,同时致力于玩一款带有球的抽象游戏;玩《洛克人》便是在不同“平台间”跳跃与射击敌人的同时不断盯着一个机器人看。

当然了,我们都理解这些,这并不是什么秘密,但我认为当我们使用比喻提到这些抽象活动时可以更加随意,即有时候我们会感受不到它们与我们所认为的情况是不同的。这也是一种奇怪的现象,即我认为我们有时候会察觉在电子游戏的一些非常特别的例子中(如“我的角色可以在无形之中扛起5个巨大的武器是件多么奇怪的事”),我们会忽视围绕着这一点的抽象性和荒谬性,并赋予其一个含义:那些并不是武器,它们一点都不打,可没有5个那么多,他并未扛起任何东西之类。

当《疯狂橄榄球》的玩家投出一颗球时,那里并没有橄榄球,没有投掷动作,没有橄榄球玩家,我并不是因为感受到那些只是模型,像素和声音文件才这么说,我只是基于一种理念和实践层面进行表达,这里所使用的名词和动词与我们用于形容的名词和动词没有多少关系。想象真正的橄榄球与《疯狂橄榄球》中的橄榄球之间的区别—-这种区别不只清楚地体现在物质性上,同时也体现在它的使用对象和方式(包含创造性或无意识的使用)。投掷行为也是如此,直到“球”到达目的地玩家按压按键所触发的模拟行为也是显著区别于真正的投掷行为,这涉及操控行为的复杂性,做对或做错的多种方法以及影响结果的各种元素。

这并不是橄榄球选手,并不是在投掷,并没有橄榄球,并不是在橄榄球场地上,并不是在一款拥有橄榄球的游戏中。这是一个基于明显的实体模拟的例子,至少从概念层面上看是这样的,接下来会发生什么则是关于真正发生什么情况的模拟。

不管一款游戏的图像有多逼真,不管市场营销者如何尝试着说服我们模拟按键按压取代普通按键按压,屏幕上所发生的与我们脑子里所发生的仍存在巨大的差别。

为了呈现这一区别的其它面的解释,让我们着眼于电视节目是如何描述电子游戏的行动,即在专业动画师肩负着添加一些让人兴奋的电子游戏般的序列内容时。《House》,《Futurama》和《Psych》都做到了这点,我敢保证还有许多我并不熟悉的例子。在这些例子中,角色就好似在虚拟世界中自然地出现并移动。他们会弯腰捡东西,会躲在爆炸点的附近,还会倾斜身体与其他人低声说话。

自从1977年Warren Robinnet面向雅达利创造了《Adventure》以来,我们便会经常从中借取某些内容。这真的有点奇怪,或者说在任何事件中并不是关于人们如何捡起某些东西,而是我们必须在某些内容变成一种惯例前先创造它。现在距离那时已经过去了35至36年时间,特别是对于那些年龄不到35或36岁的人来说,将所有弹药运往我们的军库,让我们能够在此直接装载手枪似乎是件很随便的事。

让我们回到《洛克人》通过跳跃导航关卡中:代码的变化在于虚拟空间中存在一个可移动的区域,在这里玩家拥有近乎直接的控制,并将穿越系统危险直至满足目标条件。存在一些方法能够帮助玩家通过这些空间移动他们易受攻击的范围,典型的方法便是水平奔跑并背对着模拟重力向上跳跃。行动通常是独立的—-攻击或不攻击,或者跨越一个简单的规模在一个单一维度上发生变化—-保持跳跃以跳得更高。

我们的脑子里(而不是在游戏中)会出现所有的其它事物,这是处于我们所面对的装饰性意象以及我们所参与的抽象活动的交叉点上。这并不是一个等待我们解决的问题。这也不是对于电子游戏的批评。作为开发者,这甚至可以说是一个机遇,因为这将提醒着他们为了创造重要的感觉还需要执行哪些内容,这同样也是关于想象力和声音的作用的提醒,因为这有可能让玩家感受到我们想要通过编程方式做出的表达是模糊或无效的,而这也有可能成为他们对于游戏的唯一关注点,并难以专注于一些更具凝聚力的结果。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转功,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Gameplay is Inherently Abstract

By Chris DeLeon

Pinball and videogame designer George Gomez, interviewed for the documentary Tilt, explained that pinball gameplay is inherently abstract, but that as a designer he strives to use theme-based gameplay concepts to help make it less abstract. The player is toggling lever positions with electromagnets to knock a metal ball around a painted piece of wood, but when people see the games their thoughts are first taken over instead by racecars, cartoon characters, sci-fi themes, licensed movie elements, or other artistic decoration. Beginning in the early-mid 1980’s, pinball designers sometimes added a few playfield elements or goals connected loosely and conceptually to the theme, and in that way attempted to make the game somewhat less abstract (in Steve Ritchie’s High Speed: advance the traffic light from green to yellow to red, then run the red light, then “escape” the police – but it’s all just a ball rolling around banging into stuff).

Although pinball is a far more severely constrained medium for expression than videogames, due to its reliance on cheap, reliable, physical mechanisms instead of animated graphics, the underlying gameplay in videogames is also inherently much more abstract than we often acknowledge.

As is usually the case for my writing about videogames, I don’t have in mind here the computer games that evolved from board games – turn-based, tile-based, or menu-driven strategy – which is perhaps more trivially understood as abstract. Rather my emphasis is the seemingly literal and situated games in which players run, jump, collect, shoot, open, and otherwise interact with spatial environments in real-time.

The player isn’t jumping, the player character isn’t jumping, there’s something else entirely going on that we reason about through metaphor for jumping. Under the surface what’s going on is far more complicated and unnatural than jumping, yet on the surface what’s going on is far less complicated than jumping – more natural even than jumping.

I do not wish to overstate this case, because taken to its extreme I’d argue against myself here, too. The vogue idea from the mid-2000’s that gameplay can be productively reasoned about as meaningless rectangles bouncing around and interacting loses much more than it adds to the conversation. Of course it matters that what I’m seeing is a ninja, a frog, or a spaceship, and not merely for the affordances and expectations that we infer from that imagery.

For that point, here again I’ll point to pinball: at most a few scoring events on any given table are even loosely grounded in the game’s theme or metaphor (“slaying the dragon” or “defending Paris”), the rest are just abstract (“1000 points” or “increase bonus multiplier”). Prior to the early-mid 1980’s virtually none of the scoring events connected to the game’s theme. The art was literally, at one level, merely decoration atop a completely unrelated abstract game, akin to the patterns painted on the backside of a deck of cards, and in the 1930’s when pinball started truly abstract patterns like the back of a card were occasionally used on the tables (see: Ballyhoo).

Yet despite that massive disconnect between the art and the gameplay it still mattered, when the industry began to outgrow sport allusion and sport metaphor toward miscellaneous other themes in the 1940’s and 1950’s, that the games depicted fighter planes, fishing, cowboys and cowgirls. It clearly mattered to a degree that it hasn’t for playing cards, since while any playing card patterns besides the cheapest generic styles are a fairly uncommon novelty, differences in backglass art and cabinet decals played an important part in selling new large, heavy, costly arcade machines for decades between pinball’s major gameplay breakthroughs.

The visuals are planting seeds in our heads about what we’re supposed to be imagining when we play or think about the game. It’s filling us with associations that we cannot look away from while still continuing to play. To play Terminator 2 pinball is to look at illustrations and elements from the movie while managing to play a largely abstract game with the ball; to play Mega Man is to stare continuously at a little robotic man while “jumping” between “platforms” and “shooting” at the enemies which follow simple patterns to function as dynamic obstacles.

Of course we all understand this, it’s hardly a mystery, but I think we can become so casual or careless in referring to these abstract activities by their metaphors that we sometimes lose a sense for just how unlike they all are from what we call them. This is also an oddity that I think we occasionally become aware of in very isolated cases in videogames – “oh how strange that my character can invisibly carry 5 large weapons” – though in that focus we overlook the abstractness and borderline absurdity of everything surrounding that point and giving it meaning: those aren’t weapons, they aren’t large, there aren’t 5 of anything, nothing is being carried, and so on.

When the Madden player is throwing a football there’s no football, there’s no throwing, and there’s no football player – and I don’t mean this in the trivially reductive sense of, sure, those are models and bits and pixels and sound files, I mean this very much still at a conceptual and practical level as well, in that the nouns and verbs relate in very, very few ways to the nouns and verbs we use to refer to them. Think about the differences between a real football and the football in Madden – the differences not only obvious in its materiality but in what it can be used for and how (creative or unintended uses included). The same goes for the act of throwing, and how that simulated act from the player’s button press up until the “ball” (or maybe ball’ for ball-prime, even?) reaches its destination differs vastly from what can be said about a real physical act of throwing, in the complexity of conducting the act, in the versatility of ways to get it right or wrong, in the factors affecting the outcome.

It’s not a football player, not throwing, a not football, on a not football field, during a game of not football. And that example is situated in a case for which there is a clear physical analog that is, at least at some conceptual level, being simulated, yet what is going on is so far from a simulation of what actually happens or how that I fear that using the word risks significant misunderstanding.

No matter how cinematic or photorealistic a game’s graphics may appear, and no matter how much marketeers try to convince us that arm waving to inefficiently and imprecisely simulate button pressing is going to somehow replace button pressing, there’s still a vast gap between what’s happening on screen and what’s happening in our heads.

For an illustration of the other side of this difference, look at how videogame action is depicted in television shows, when professional animators are tasked with putting on some exciting videogame-like sequences. House has done this, Futurama did it, Psych did as well, and I’m sure there are countless others that I’m not familiar with. It’s as though the characters are literally there, present and moving within the virtual world. They bend down to pick up objects, wince at nearby explosions, and lean in to whisper to one another.

Ever since Warren Robinnet made Adventure for Atari 2600 in 1977, we’ve usually picked things up by walking over them. Lest anyone forget, that’s really sort of weird, or in any event not how things actually get picked up, and someone had to invent it before it could become a convention. Now some 35-36 years later, and especially for people younger than 35-36, it seems pretty casual to run over the top of a loaded gun (gun-prime?) to instantly transfer all ammunition from it into our inventory, from which we can directly reload a gun in hand.

To return to Mega Man’s navigating the level by jumping: what’s going on in the code is that there’s a moveable region in virtual space, over which the player has near direct control, to get past systematic dangers until goal conditions are met or reached. There are very few ways for the player to move their vulnerable region through the space, typically running horizontally and jumping upward against simulated gravity, and that control happens by a few among a dozen or so switches plus several directional or analog levers. The actions are generally discrete – attack or don’t attack – or if varied then varied on a single dimension across a simple scale – hold jump to jump higher.

All of the other stuff is just going on our heads, not in the game, at the intersection of the decorative imagery we’re shown and the fairly abstract activities we’re fiddling with. That’s not a problem to be fixed. That’s not a criticism of videogames. As developers, that’s even an opportunity, since it’s a reminder of just how much doesn’t have to be implemented to get the important feeling or sensation across, and it’s also a reminder of the power of imagery and sound to stir up associations, feelings, or ideas in players that our best efforts to embody programmatically would be so inarticulate and inefficient as to become the singular focus of the game, distracting away from building upon that one effect toward some more cohesive end.(source:hobbygamedev)