有关游戏设计过程的前提(一):执行

作者:Tim Huntsman

对于每一款设定了较高的设计或游戏玩法标准的游戏来说,有许多游戏并未达到这样的标准。为什么会这样?我发现许多可能的原因。许多游戏是由那些信口开河而 非真正将成功作为一大目标的人所创造的,许多设计师还是新手,并不清楚别人对他们的期待,并且只有少数开发公司为创造和执行游戏创造了正式的设计过程。(请点击此处阅读本文第二部分)

如今的书籍和杂志只关注与游戏设计的技巧。因为这是一项具有创造性的任务,每个人都认为自己能够做到这点。如果这是事实,那便会出现更多带有更棒的控制,更棒的AI,更多用户友好型前端,即使是12岁少年也能够快速掌握的游戏机制,以及在软件中拥有较少的游戏阻塞物等情况。但是我的一个朋友却跟我讲述了一个严酷的事实,即一家大型开发商/发行商的开发VP问他,为何自己要投资140万美元于他的项目中而不只是将钱投资于股票市场中。答案是什么。如果游戏拥有有效,即时的设计并且非常有趣,那么他的投资便有可能得到巨大的回报。

这一关于设计过程的引用可以分解为三大部分:执行,思考和需要。第一篇文章将解释你在准备创造一款游戏时需要做什么。第二篇则是着眼于你在制作一款游戏时需要思考什么,最后一篇文章将明确你在执行这项任务时需要什么。

做什么:

设计师的主要任务便是设计游戏。这听起来很简单;但却是必须做好的事。比起编写一些关于你所想出的理念有多酷的段落,写下无数没人愿意看而只有作者会逼迫自己看的细节内容,设计一款游戏需要做的更多。

优秀的设计是关于执行理念和细节。为了明确你的游戏需要什么,你需要清楚你身边有什么。你需要知道市场可能会支持什么,市场所厌倦的是什么。你需要了解你的公司可能或不想要看到什么。总之,你需要在开始前先问自己一些问题。

1.提问题

这与听起来一样简单,你需要在开始写下设计文件前问一些问题。在你炮制你的下一款畅销游戏前你需要考虑许多事。不管怎样这一列表还是很详尽的。有些问题可能与你们各自的情况相关——并不是所有的游戏都需要考虑同样的情况,同时有些项目可能需要额外的问题。决定要问怎样的问题是你的工作最重要的一部分。

现在的趋势是什么?

当前的设计趋势是什么?浏览贸易地图并明确什么或谁创造了巨大的反响。技术提供给我们能力去拓展更多领域,创建并审视更大的世界,实时照亮它们,维持一种可被接受的帧率,我们发现玩家对于娱乐拥有更多的期待。维持玩家兴趣的创造性公司所采取的一种方法便是模糊已确定的类型之间的界限。这能帮助我们挑战那些“已被接受”的内容并揭去创造性设计的面纱。

趋势同样也存在于像旋转和实用性中—-竞争如何通过提高给玩家对于游戏环境的更多控制权而赋予他们能力。现在摔跤游戏的一大标准便是需要从从头开始创造定制的摔跤手。这成为《WWF Warzone》在美国最受关注的功能,现在THQ和艺电也整合了更多“赋予玩家能力”的理念到游戏中。

市场营销的寻求是什么?

这可以被重申为“游戏玩家的寻求是什么?”着眼于市场营销专家,他们应该拥有关于人们想要什么的理念。他们会进行焦点小组测试,他们应该通过反馈去编制数据。同样地,他们还会考虑市场能够忍受什么。“仿照“产品的销量总是不及它们所仿照的对象。

现在我们可以使用怎样的工具?

例如,着眼于动画需要怎样的动作捕捉。不要误会,我并不是在提倡一个“无时无刻捕捉所有动作”的游戏世界,但这样的数据也是创建待遇优厚和备受尊重的动作编辑器的基础的一种有效方式,能够调整动作去匹配设计。

3D程序编写和世界建造工具仍然是帮助或隐藏设计过程的最受欢迎的例子。如果你需要匆忙创建一个概念原型或者如果你需要在失去游戏授权前赶上圣诞购买季前完成创造,那么现有的工具便能够帮助你做到这点。

工具将帮助你创建一个设计原型而了解某个理念。它们同样也会帮助你更轻松地完成工作。循环技术并不是一个糟糕的理念,除非你的公司唯一能够宣传的技术与游戏玩法无关。

有些类型适合某种特定的音乐,通常是一些专业且有名的乐队或个体。听听什么是好的,会发生什么,然后整合其风格到你的游戏中。有些市场营销人士将支付你的大笔开发预算与一些乐队或个人签约让他们为你的游戏制作音乐,但据我了解,人们很少会愿意购买一款拥有自己曾经在广播中听到的音乐的游戏。在特定情况下让较有名的人制作音乐将能够让游戏变得更酷并在网上或杂志中创造一些噱头,但这却不能从根本上动摇消费者,这也不能保证游戏的宣传能够即时且有效地呈现出来。如果存在任何问题,一种可靠的解决方法便是尝试着获得你想在自己的游戏中使用的某首歌曲的同步授权(你将获得使用某首歌的权利,但却不能使用最初创造者所创造的音源)。

有些公司已经浪费了许多钱去尝试获得一些音乐人才在自己的游戏中做出贡献,并将其当成是游戏的主要市场营销元素。Rob Schnider作为《A Fork in the Tail》的主唱或Christopher Lloyd作为《Toon Struck》的主唱是否重要?如上,通常情况下大多数玩家不会因为一些名人声音的出现而去购买游戏。

获得一些能够匹配游戏态度的内容(或人),这将能够提高玩家的游戏体验。这也才是你们真正需要担心的事。

完成了什么以及是如何完成的?

我会在之后关于临界评定的“思考”部分谈论到这点,但当你最初开始进行设计时,这真的是一个非常重要的问题。我们并不需要你谈论一个众所周知的故事,或者创造一款已经存在的游戏,再或者重新演绎已经上道的类型。你应该进行研究并通过研究获得学习。你应该玩游戏。你需要知道存在什么,那些内容已经有人做了,并且现在的标准有多高,如此你才能够更好地明确自己该怎么做。

与其它娱乐业务一样,这里也存在一些如何呈现理念的基本规则和格式,以及一些人们不愿再看到的内容。自Smith/Corona(游戏邦注:40年代的美国打字机)时代以来,电影和电视关于电视或银幕都有了标准的脚本格式。这些格式不只是人们所期待的,同时也是人们所需求的。

而我们的业务有点不同。它的“年龄”还不足以拥有标准和指南,但我们正在朝着产业标准和实践的“广谱规范化”前进。简单地来说,传统拥有繁殖的期待。我们需要在制作某些内容前回答一些特定的问题。这是你的工作。你需要回答这些问题,如此项目中的所有人将为了获得信息并清楚需要做些什么以及该如何做等问题前来咨询你或你的搭档。

设计文件倾向于分为两种格式:它们可能会简单地描述一个游戏理念从而让上层管理者能够赞同该理念,然后将其丢进某人的文件柜并永远被忽视,或者它们如你们当地黄页般大小,拥有只有编写之人在乎或愿意去阅读的任何可想而知的细节内容。

在尝试着维持设计员工与制作团队间的工作交流时,我想出了一个关于“功能导向型”文件理念,即能够确保团队中的所有人都即时获得相关信息,不管是设计发生改变或重新进行设计。

如果你着眼于一份制作电影脚本,你将会在整个脚本的任何特定点上看到不同颜色的页面。这些页面代表的是从电影开始后脚本所做出的改变。这些颜色让演员和工作人员能够遵循改变,从而保持连续性,并确保在做出更新时所有人都能处于同一页面。

与脚本一样,设计文件中的内容也会因为环境,人才或基于管理某些部分的创造性问题的解决或制作团队而发生改变。这些改变不仅需要标注出来,同时也应该发送给那些可能受到影响的人手中。

功能导向型设计文件

我们的功能导向型设计文件始于一个基本格式,即能够保持参与文件设计的6个人即时获得相关信息。它的设计不仅是作为团队中所有人的向导,同时也是将我们带向3款同时进行的不同游戏的活跃文件。

我们将设计文件置于我们的LAN上,并且设计团队可以不断往里面添加内容或同时更新文件。版本控制也是一个简单的软件问题,任何时间都不允许超过一个人致力于一份单独的子文件。

文件本身整合了一些能够有助于组织内容的功能,包括传达像引擎需要做些什么,AI的要求,游戏模式,动作要求等等内容的主要标题。在这些标题下便是一些特定的子文件能够解释团队中的个体需要在设计中处理的功能。不管何时一旦敲定了一个新设计功能,我们便能够通过电子邮件并附加关于虚拟文件的超链接给相关团队成员。我们之所以可以这么做是因为文件是由我们整个团队进行编写的。

子文件本身是以带有与目录相联系的标题数字的数字模板形式呈现出来。这让我们能够在致力于不同产品的设计层面时通过功能或项目去区分文件。模板能够为每个功能推动更加详细的设计并帮助设计师事先回答一些问题,并在项目制作时估计到更加全面的设计。

这一模板同样也允许我们能够设计更多游戏版本。有些设计功能已经在一系列发行时进行了分层,你将总是处于你所思考的任何功能的同一页面上。

关于设计文件的总体规划便是将其与基于同样模式的技术设计文件和一些像MS Project等调度软件连接在一起。这拥有额外的能够让我们引导任何对于里程碑或新设计功能预算的影响。

模板:

大多数美术师和程序员未阅读设计文件的理由是(如果其中包含了任何使用的设计功能),它们经常是藏在一页又一页连续的段落中。简单地说,没有人想要艰难地穿越它去获得自己想知道的内容。基于这种形式的模板将作为较小的相关组块中可被消化的主要功能。

我们需要记得,这是功能导向型设计文件,这意味着它将带有一些特定的目标,并且这些目标能被分解成一些可行的位体。

0目录—-这需要包含你正在处理的每个主要标题。这应该包含像AI,碰撞,关卡设计,前端逻辑流程,控制输入内容等等部分。

1功能标题—-描述并列举讨论中的问题/功能。存在于TOC中的数字索引让你能够在项目进行时轻松找到它并对其进行分类。

1.1接触并“参见”信息—-简单的:关于谁设计某一功能以及它在外部所相关的其它文件的接触点。

1.2目标——一列相关目标,包含你在执行这一功能以及所述问题的可能解决方法的问题。

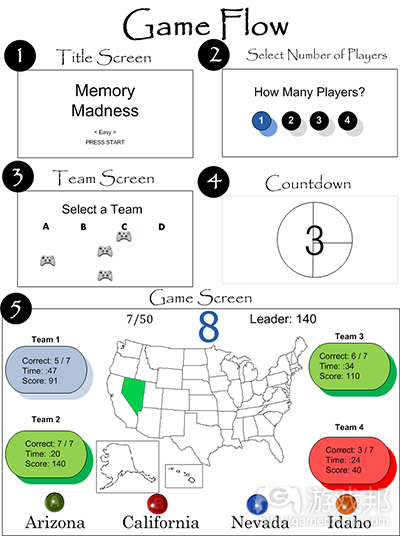

1.3执行——你将如何影响功能。在此你包含了可能陈列出处于讨论中并且是所有参与者都需要知道并遵循的设计功能的公式,图标或流程图。

1.4影响—-这些功能将如何影响现状。你不能总是对其进行预测,但在我们的情况中,我们正在对现有引擎/游戏做出改变,所以一些改变可能会影响到我们现在正在执行某些功能的方法。对此的一个例子便是为摔跤选手设定一个新的行动,并当我们已经超载时需要一次按键按压动作去做到这点。关于这一标题的另外一种使用方法便是帮你识别你可能需要的额外资源,并计划相关需求以确保功能相一致。

1.5至1.8的任务和问题:

设计师

程序员

美术师

2D

建模人员

动作

声音

对于开发团队的每一部门都需要有“任务和问题”的部分。这让设计师,美术师,程序员或声音设计师能够直接跳到与他们相关的问题中而无需再过滤所有的其它内容。这也让设计团队能够在不能接近可以直接回答问题的人的时候询问他们所具有的问题。

你同样也想要某种方式去标注出因为某些原因被丢弃或隐瞒的功能。你不想身处这些功能,因为它们可能会采取某种方法回到当前设计中或出现在续集里。

在我们的例子中,我们正同时进行多款游戏的设计。每个标题都将进一步扩展成3个子标题,即根据不同版本和颜色进行划分,让它们更清楚地呈现于屏幕上。

电子邮件和超链接:

基于在线设计文件,我们能够在设计,改变或丢弃功能时发送电子邮件给所有相关人员。除了在电子邮件中说“这一功能已经被设计,改变或丢弃”外,我们也能够添加超链接让对方可以直接到达他们想要阅读的页面。

电子邮件拥有另外一个考虑因素,即项目管理者在阅读电子邮件时将会意识到这点。这能够帮助他维持团队的整体责任感,即关于每个人的工作是什么,在时间快到时他们该如何执行它等等。这类型结构有助于HTML类型的文件。现在我们使用了MS Frontpage设置了这种简单的在线文件。当然了,你也可以使用Dreamweaver,如果你想这么做的话。这让任何拥有网页浏览器的人可以访问设计文件并轻松导航到自己想要的信息。更棒的是,你还可以创造《圣经》般的艺术,连通相连接的缩略图和实际照片参考,确保你的所有资源都是可行且受保护的。

下一部分我们将进一步讨论有关作为设计师的你应该做些什么等问题。这同样也包含了我的“从不”列表,即我在过去几年里通过产业中的朋友以及自己的尝试所得到的经验。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转功,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

A Primer for the Design Process, Part 1: Do

by Tim Huntsman

For every game that sets the high-water mark in design and/or game play, there are dozens of titles that don’t. Why is that? I’ve discovered a number of possible reasons. Many games are made by people who shoot from the hip instead of taking a good and proper aim at success, many designers are relatively new to their jobs and aren’t certain what’s expected of them, and few development companies have established a formal design processes for creating and implementing a game.

Books and magazines are only now dedicating themselves to the craft of game design. Because it is an inherently creative task, everybody thinks they can do it. If that were true, there’d be more games out there with better control, better AI, more user-friendly front-ends, game mechanics that the average 12 year old can immediately pick up and play, and less games clogging the clearance bin at Software, Etc. A harsh reality story a friend of mine likes to tell regards a VP of development-type for a larger developer/publisher asking why he should invest 1.4 Million dollars in his project versus simply investing it in the stock market. The answer? The possibility of an astounding return on investment provided the game is well designed, on time, and fun to play.

This primer for the design process is broken into three separate sections: Do, Think, and Need. The first article explains what you need to do to get ready to make a game, the second looks at what you need to think about while you’re making the game, and the final piece examines what you’ll need to do the task.

What to Do:

The primary task of the Designer is to design the game. That sounds simple; it was meant to. More goes into designing a game than writing frilly paragraphs about just how cool you think your idea is, just more is required than writing a massive, hernia-inducing tome of endless and unnecessary detail that no one but the author can bring themselves to read.

Good design is about the implementation of ideas and details. To know what you need for your game, you need to know what’s going on around you. You need to know what the market might support and what the market is sick and tired of seeing. You need to know what your company (or those funding your company) may or may not want to see. In short, you need to start by asking some questions.

1. Asking questions

This is as simple as it sounds, you need to ask questions before you begin to write your design doc. There are a lot of things to consider while you’re cooking up ideas for your next platinum-selling title. By no means is this list all-inclusive. Some questions might be irrelevant to your respective situation -not all games need the same considerations- while some projects might require additional questioning. Determining which questions to ask is one of the most important parts of your job.

What are the current trends?

What are current trends in design? Scan the trade-mags and look at what and who are causing a buzz. As technology gives us the ability to push more polys, build and view larger worlds, light them in real-time, and maintain an acceptable frame-rate, we see that gamers are expecting more from their entertainment. One way that certain creative companies have kept the ongoing interest of gamers is to blur the lines between established genres. It helps us to challenge what’s become “accepted” and push the veil of innovative design.

Trends can also exist in things like options and utilities-how the competition is empowering the player by giving them more control over their game play environment. One standard now being called for in the wrestling genera is the need/want to create custom wrestlers from the ground up. This became the most talked about feature on the US side with WWF Warzone, and now THQ and EA both incorporate more “player-empowering” concepts into their titles.

What is marketing looking for?

This could be restated as, “What are gamers looking for?” Look to the marketing experts, they should have a good idea about what people want. They do the focus-group testing, they should be compiling data from this feedback. Also, consider what the market can stand. “Me-too” products usually sell much less than the product they’re emulating.

What current tools do we have access to?

For example, look at what motion capture did for animation. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not advocating an “all motion capture, all the time” game world, but that kind of data is an excellent way to build a foundation that your well-paid and well-respected motion editors can start from, tweaking the motion to fit the design after the fact.

3D authoring and world-building tools are still probably the most prevalent example of things that can help or hinder the design process. Preexisting tools can also give you jump if you need to either prototype a concept in a hurry or if you need to race to make the Christmas buying season before you loose the license for your game.

Tools give you a way to either prototype a design to get an idea across. They also allow you to get a job done with less hassle. Recycling technology is not a bad thing, unless the only thing your company can hype is tech with no game play.

Some genre’s lend themselves to certain kinds of music, often from professional named bands or individuals. Take a listen to what’s good, what seems to be happening, then incorporate its style into your title. Some marketing folks will fork over a chunk of your development budget to sign bands or individuals to do the music for your title, but it’s been my understanding that very seldom, if ever, will a person’s decision to purchase a title be based on the fact that someone they may have heard on the radio once did the music for the game. In certain cases having a named talent do the music might add to the “cool” factor and help generate a little buzz on websites or the odd magazine, but it’s not going to sway the consumer and it can also be a huge licensing hassle with no real guarantee that what gets written for the game will be delivered on time or be any good. If there’s any question, a good solution is to try to get a synchronization license (Where you get the right to cover the song, but not to use the original recording by the original artist) for a piece of music you’d really like in your game.

Some companies have been known to waste a ton of cash trying to get a particular vocal talent or talents to act in their game as, unfortunately, a major marketing aspect of the title. Did it matter that Rob Schnider was the main vocal talent in A Fork in the Tail, or Christopher Lloyd was in Toon Struck? As above, more often than not most gamers won’t buy a title simply because there’s some celebrity voice actor that they button past in the first 2 seconds of hearing it in order to get back to the game play.

Get something (or someone) good that fits the attitude of the game, and it will increase the gaming experience for the player. That’s all you need to be worried about.

What’s been done and how was it done?

I talk about this later on in the “Think” section about Critical Evaluation, but this is a very important issue when you first start your design. There’s absolutely no need for you to tell a story that’s already been told, or develop a game that’s already been done, or rehash a genre that’s on the way out. Do your research and learn from that research. You should be playing games, plain and simple. You need to know what’s out there, what’s already been done, and how high the bar has been set so that you can clear it.

2. The Working Design Document

Once you’ve focused your ideas, its time to think about the design doc. The design doc acts as a script; it should be giving every other professional involved with the product a more than firm idea of what they need to know to implement their portion of the product.

Like other parts of the entertainment business, there are some basic rules and formats for how ideas are presented, as well as a few things that people no longer want to see. Publishing has its “double spaced 12-point Courier font” from the old Smith/Corona days, and film and TV have standard script formats for either television or the silver screen. These formats are not only expected, but also demanded.

Our business is a little different. It’s not quite old enough for standards and guidelines to exist, but we’re moving into the “broad spectrum formalization” for industry standards and practices. Simply stated, tradition has bred expectation. Certain questions should be answered before the thing is sent to production. This is your job, O Maintainer of the Creative Vision. You need to answer these questions and more, as everyone on the project will be coming to you or your people for information and the lo-down on what needs to happen and, more importantly, how it’s supposed to happen.

Design documents tend to fall into one of two formats: they either loosely describe a game concept so upper-management can sign off on the idea, then get dropped into someone’s filing cabinet never to be read again OR they are the size of your local Yellow Pages, filled with every imaginable detail that no-one but the person who wrote it cares about or is willing to read.

In an effort to maintain the working lines of communication between the design staff and the production team, we came up with the idea of a “feature-oriented” document that could keep everyone on the team up to date and informed whenever a design change was made or redesigned.

If you look a production movie script, you’ll see that there are different colored pages at any given point throughout the entire script. These pages represent changes that have been made to the script since the start of filming. The colors allow the cast and crew to follow the changes and thus maintain continuity and keep everybody -pardon the unintentional pun-on the same page when updates occur.

Like a script, things in a design document will change due to circumstance, talent, or innovative problem solving on the part of management or the production team. These changes should not only be noted, but also sent out to the people whom they affect.

The Feature-Oriented Design Document

Our feature-oriented design document began as a basic form that could help keep the 6 people involved with the design document up to date. It was designed not only as a fluid guide for everyone on the team, but also as a living document that could carry us through the ongoing design of 3 different games.

We put the design document on our LAN, with the design team continually adding to or updating the document at the same time. Version control is a simple matter of the software (in this case MS Word) not allowing more than one person to work on an individual sub-document at any given time.

The document itself incorporates a couple of features that help with keeping things organized, including major headings calling out important items like what the engine needs to do to, AI requirements, game modes, motion requirements, and on and on. Under these heading are the particular sub-documents explaining the features or functions that individuals on the team have been tasked with designing. Whenever a new design feature is nailed down we can send out updates to the relevant team member through E-mail with a hyperlink attached to the virtual document for easy access by team members. We can do this because the document is being written with the whole team in mind.

The sub-documents themselves take the form of a numerated template with the heading numbers tied to the table of contents. This allows us to sort these documents by feature or project when we work on layers of design for separate products. The template helps push for a more detailed design for each feature and also helps the designer answer questions up front, allowing for a more thorough design when the project hits production.

This template also allows us to design for more than one version of the game. Some design features have been layered to appear over a series of releases and as such, you’re always on the same page with whatever feature you’re thinking to forward.

The master plan for the design document is to have it linked with both a Technical Design Document that’s arranged in the same manner and some sort of scheduling software like MS Project. This has the added function of allowing us to asses any impact to milestones or budget new design features may have.

The Template:

The major reason most artists and programmers don’t read the design document is that, if there are any practical design features contained within, they are usually buried in page after page of ongoing paragraphs. Simply stated, no one wants to weed through it to get to what they need to know. The template, in this form, serves the major function of being digestible in small relevant chunks.

Remember, this is a FEATURE-ORIENTED design document, which means that it is put together with certain goals in mind, and these goals are broken down into doable bits.

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS – This needs to contain EVERY major heading that you’ll be dealing with. It should include sections like AI, collision, level design, front-end logic flow, controller input, and the like.

1 FEATURE HEADING – Describes and numerates the issue/feature in question. The numerical index, established in the TOC allows for easy finding and sorting once the project is underway.

1.1 Contact and “See Also” Information – Straightforward: Point of contact for who designed the feature and what other documents it relates to outside of this one.

1.2 Goals – A bullet list of associated goals including problems you may encounter implementing this feature and possible solutions to said problems.

1.3 Implementation – How you’re going to affect the feature. This is where you’d include formula, diagrams, or flowcharts that layout the design feature in question that all relative parties may need to know/follow to get the feature up and rolling.

1.4 Impact – How this feature will impact the current status quo. You can’t always crystal ball this, but in our case we’re making changes to an existing engine/game, so some changes do affect the way we’re currently implementing some features. An example of this would be having a new action for a wrestler to do, and needing a button-press to pull it off when we’re already overloaded here. Another use for this heading is to help you identify extra resources you may need, and schedule relevant needs to bring the feature into line.

1.5 to 1.8 Tasks & Questions for:

Designers

Programmers

Artists

2D

Modelers

Motion

Sounds

There must be “Tasks & Questions” sections for each arm of the development team. This allows the Designer, Artist, Programmer or Sound Designer in question to skip straight to the task relevant to them without having to filter through all the other text. This also lets the design team ask any questions they may have at a time when they might not have access to the person that could immediately answer it.

You’ll also want some way to tag features that have been dropped or held back for whatever reason. You don’t necessarily want to delete those features, as they may make their way back into the current design or appear in the sequel if you’re doing one.

In our particular case, we’re working on the design for several titles at one time. Each heading is further expanded into 3 sub headings-one for each version-and color coded to make reading and separating them on-screen a little easier.

E-mail and the Hyperlink:

With the design doc online, we’re able to send intranet e-mail to all concerned parties when a feature is designed, changed, or dropped. In addition to the email saying, “This feature has been designed, changed, or dropped,” we can also add a hyperlink which, when clicked upon, will take the concerned party directly to the page(s) they should be reading.

The e-mail has a secondary consideration in that the Project Manager will know when and if the Email is being read. This helps in maintaining team accountability for what each person’s job should be, and how they need to implement it when the time comes. This kind of organization lends itself to a HTML-type document as well. We’re currently setting up just this kind of accessible, online document using MS Frontpage. You could also use Dreamweaver if you were so inclined. This allows anyone with a web browser to access the design doc and very easily navigate their way to whatever piece of info they need. Even better, you can do things like create art bible’s, complete with linked thumbnails and actual photo reference on the network, making sure all or your resource is available and protected.

The next section (THINK) will go deeper into asking questions about what you’re supposed to be doing as a designer. This also includes my list of “Nevers,” garnered over the years both from friends in the industry and from simply doing things the hard way.

Tim Huntsman has been with Acclaim Studios, SLC for over 4 years and is the Lead Designer for Acclaim’s next-gen wrestling title. He has worked on the ECW wrestling franchise as well as the genre-defining WWF Attitude for PSX and N64, projects that taught him more about professional wrestling than he ever thought he’d know. When not working on games and their design, he’s playing guitar in experimental projects, writing various forms of fiction, painting in the Sumi-E style, and fencing (with swords, not wooden planks.)(source:gamasutra)

上一篇:如何理解高低层次的游戏设计

下一篇:解析游戏关卡设计中的构图原则

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号