分析游戏重玩性之叙事篇(1)

作者:Ernest Adams

是什么促使一款电脑游戏呈现重玩性?为什么有些游戏具有重玩性而有些没有?(请点击此处阅读本文第2篇)

基本上,任何游戏都应该具有重玩性。如果你到一家玩具店,花了20或30美元购买了一个盒装棋盘游戏,然后回到家发现你只能玩一次游戏,你肯定会非常愤怒吧。然而这种情况经常出现在计算机游戏中,而我们的用户有可能会因此抛弃它。然而重玩性并不是一个意外事件:这是作为设计师的我们可以有意创造的某些内容。

让我们从是否想要这么做这一问题开始。从单纯的利益角度来看,重玩性并不总是件好事。如果一款游戏无止境地重玩下去,我们的用户便没有理由去购买其它游戏。我们需要他们去购买新游戏从而确保我们不会失业,所以我们拥有财政动机在游戏中创造特定的生命周期。然而我并不知道任何开发者是否会这么想。首先,因为飞速发展的技术,大多数游戏已经拥有特定的生命周期;当Intel和AMD正在尽所能地确保我们游戏在几年内将被淘汰时,我们也不需要特地去创造什么。但更重要的是,我们中的大多数人都带有某种创造性骄傲。我们希望人们能够长时间继续玩我们的游戏。

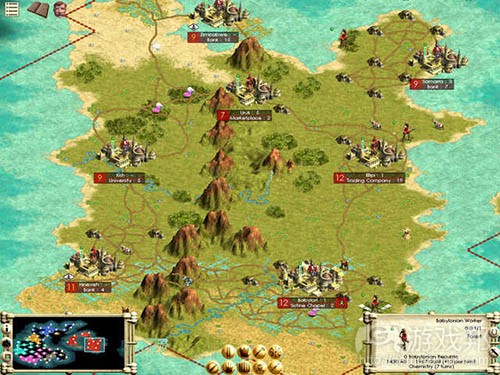

我们尊重像《文明》以及《神秘岛》等玩家玩了好几年的游戏,我们也尊重那些能够创造如此内容的设计师们。

所以假设我们想要创造一款具有重玩性的游戏,那么到底怎样的内容会影响重玩性呢?撇开技术不说(我们控制不了),我们该如何设计一款具有重玩性的游戏?在本文的第一部分中,我们将处理游戏中的叙述效果,而在第二部分我将着眼于游戏机制。

游戏中的叙述,也就是故事情节倾向于较为固定且基于线性。尽管经过25年的研究,仍然没有人能够设计出真正让人满意的“分支故事情节。”当人们重新游戏去寻找他们一开始所错过的分支内时,他们便会快速通过自己已经看过的某些部分。如果叙述是线性的,就像在《星际争霸》或《暗黑破坏神》中那样,一旦你知道了故事,它便不能激励你再次游戏。幸运的是,在那些提供了足够有趣的游戏玩法的游戏中,即使你已经知道了故事,你也值得再次游戏。但对于某些游戏来说,故事便是玩家玩游戏的重要原因。一旦你解决了所有谜题并了解了整个故事,你便没有理由再继续了。对于游戏来说,如果叙述更重要,玩家便更难去继续游戏。但我认为这并不是绝对。

如果你开车到苏格兰北端,即那个海鹦窝筑在海边的悬崖上,即使是在盛夏也是雾气弥漫的一个地方,你便可以朝北看到彭特兰海湾那片变幻莫测的海域,以及没有树木的群岛:奥克尼群岛。如果你坐船前往奥克尼,你便能够看到许多比我们能吃苦的人所留下的石碑:他们是新石器时代的农民,皮克特人或维京人。在石碑间有着保留完好的小村庄Skara Brae,这里所有的墙壁,地板甚至是家具都是用石头所创造的。今天你可以站在墙顶,俯视带有用石头做出来的床,架子和橱子的房间(没有屋顶),并想象5000多年前在北海冬季的夜晚被呼啸的寒风吹打着是怎样的情况。人们穿着毛皮,围坐在炉边,烧着他们所找到的浮木,周围一片黑暗,唯一的光源便是火。

他们该如何度过着无尽的冬天呢?工作:煮饭,缝纫,照顾小孩以及修补工具。玩:唱歌,聊天,开玩笑以及大笑。做人类会做的事:吃饭,睡觉,做爱,生孩子,生病以及死亡。经历了所有的这一切,跨越一代又一代,便能够:讲故事并听他们讲故事。

所以在今天,我们能够选择的故事有许多,如果一个人花了一生的时间每天都去阅读,看电视和电影,他也不会听到同样的故事(如果他想这么做的话)。但是在古代,故事却比现在少很多,并且并未被记录下来。也许他们只会告诉一些享有特权的群组,或者甚至是个人:吟游诗人,歌手。所以当一个女人变得很老时(也就是50岁左右,如果她能从分娩中活下来),那么这个女人肯定听过同样的故事好几百遍了。

为什么他们会烦恼?为什么他们会担忧?是否因为不管何时听到任何故事总是比静默好?我怀疑是这样的。静默总是会孕育出故事,不管好坏;而在讲话中,这将变成事实。再一次地,沉默比听到糟糕的故事来的好。我相信我们的祖先之所以愿意反复听取同样的故事是因为他们所听到的都是好故事。

面对如此多的故事选择,现在我们假设,一旦我们知道故事情节,便不再想要听那个故事。这对于我们的大多数故事而言是真的:《侦探科杰克》或《龙虎少年队》中是否存在任何特定的章节值得我们看第二遍?可能并没有。但有一些故事却是我们愿意反复看,听或阅读的。我们每一年都会翻出《圣诞颂歌》,即使Tiny Tim不再符合现代人的口味,但关于那个痛苦老男人的救赎故事却仍让现代人回味不已。

我会每隔18个月便再次阅读《指环王》或其中的某些部分。我知道其故事前前后后的发展。我知道我将不会听到任何有关情节的新内容。但是将我重新带回故事中的并不是故事本身,而是叙述。

以下句子是书的结尾所出现的内容。它出现在倒数第二章节。当Frodo拿着Ring站在Cracks of Doom时,Dark Lord突然注意到他,并清楚他非常危险。

From all his policies and webs of fear and treachery, from all his stratagems and wars his mind shook free; and throughout his realm a tremor ran, his slaves quailed, and his armies halted, and his captains suddenly steerless, bereft of will, wavered and despaired.

请大声读出来,这个句子充满了诗歌的韵律。前面两个短语是基于平行结构,实际上,它们是非常完美的七音步抑扬格和六步格:

From all / his pol- / i-cies / and webs / of fear / and trea- / cher-y

From all / his stra- / ta-gems / and wars / his mind / shook free

它们甚至是押韵的。下一个短语听起来就像是伴随着重复的开首辅音的盎格鲁撒克逊的头韵诗:

and Throughout his Realm / a Tremor Ran

除了“and”以外,它同样也是由抑扬格构成:

through-out / his realm / a tre- / mor ran

然后我们回到“his slaves quailed, and his armies halted”的平行结构中。当韵律开始被打乱,就像Dark Lord遭受管制一样,机械化的世界也开始瓦解了。Tolkien是故意这么做的吗?没有其它叙述方式,但他是个诗人,他了解英语,并且有意识或无意识地,他的脑子便会使用这些知识去创造素材。此时此刻在故事中,当只有诗歌能够传达他的愿景时,他便有效地使用了这一方法。这是书中最强大的一个句子,但这也是只有你在第二次或第三次,甚至是第十二次阅读时才会注意到的内容。

讲一个很伟大的故事

不一定要是新内容才能让我们欣赏到伟大的故事。人们会去看带有完整情节的歌剧,但实际上大多数歌剧的情节都非常稀薄。他们所追求的只是表演,人声的震撼力和美感。为什么十几岁的女孩会反复看《泰坦尼号》?她们已经了解了电影情节。这是因为刺激他们感官的是叙述而不是故事。

不久前,我开始好奇该如何看待漫画书—-它们的故事总是不断持续着,里面的英雄和恶棍从不会变老也很少死去。他们会反复遭遇挫折,但很少改变是永久的。故事的呈现就好似它们是持续叙述的组成部分,当然了这是说不通的;这意味着蝙蝠侠这个正常人在将近70年间都在与犯罪行为相抗衡。漫画到底属于什么类型的文学呢?最终,我想说它们既不是小说,也不是连载故事或肥皂剧,而是传说。传说并不需要形成一个连贯的整体。可能有无数关于Paul Bunyan的故事,他从不会变老或死亡,因为每一个故事都是独立的个体。

《泰坦尼号》提供给观众超越情节本身的情感共鸣。

漫画书的发行商害怕扼杀了角色,害怕人们会期待他永远死去。他们创造了角色的来源,他们为角色的冒险设定了持续的故事,但是他们却不敢告诉人们他们将如何死去。他们仍然沉迷于自己的书籍是持续叙述的理念。至少在1986年以前都是这样的。

1986年,Frank Miller写了一部名为《The Dark Knight Returns》的图画小说。在这本书里,他讲述了蝙蝠侠最后的故事及其结局。他意识到漫画书的读者不一定都是小孩;他们已经足够成熟能够阅读蝙蝠侠的死亡故事,并且无需假设其它蝙蝠侠的故事就必须就此终结。在书的引言中Alan Moore写道:

我们所有最棒且最古老的传说都意识到了时间流逝这一事实,人们都会经历生老病死。关于罗宾汉的传说如果缺少了最终的箭射去决定他的墓穴的位置也就不回完整。若缺少了世界末日的内容,挪威传说也就失去了魅力,就像大卫·克洛科特的故事缺少了Alamo的存在也就不再完整一样。

为了为蝙蝠侠的生涯提供一个顶点,Miller并未去阻止进一步传说的创造。他只是创造了一个恰当的结局,但这并不代表传说的结束。

关于传说的另外一点便是它们不一定要相一致。我们知道它们是虚构的,并不是真实存在的。并不存在任何答案能够解释为何一个特殊版本的蝙蝠侠的命运是最终结果。在创造《The Ring of the Nibelung》时,Richard Wagner从新编写了挪威传说故事,尽管最终结果与其找到的原始资料并不相同,但其实原始资料也不一定是“准确的”。他参考的是写于中世纪使其的传说副本,作者们所记录的是更早前人们口头流传的故事的特殊版本。或者让我们看看一个更现代的例子,作者John Fowles决定不了《法国中尉的女人》的结局,所以他便创造了两个不同的结局并将其传达给读者。

我认为这是创造一款具有重玩性的叙述游戏的关键。首先,如果故事是线性的,我们就必须确保它是足够优秀且值得人们反复感受,即使已经了解了情节。要像Tolkien所做的那样,进行适当编写;要像歌剧所传达的那样,好好表演;要像《泰坦尼号》所演的那样,提供超越情节本身的情感共鸣。如果能像石器时代的歌者在北海的冬夜讲故事的话,你的用户便会愿意不厌其烦地听上无数遍。这是很困难的,但如果我们找到合适的人才并付诸承诺的话便有可能做到。

其次,我们需要避免故事看起来像是关于从未发生的“历史”记录的集合体,但却是讲述强大的英雄,伟大的事件和事迹的传说故事。那些读万卷书的人会纠结于《星际迷航》宇宙中的矛盾;几十年前,他们也是这么看待《福尔摩斯》故事的。这是因为他们将这些虚构的世界看成是客观存在的。他们这么做是无害的,但是我们必须对此有所警惕。作为设计师,如果我们将自己与现实世界的某一事件绑定在一起也就意味着亲自将自己的创造性捆绑起来,从而难以创造出具有重玩性的游戏。重玩一款游戏将创造变化,而变化则要求叙述能够容忍它。故事,不一定要是“真的”。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Replayability, Part One: Narrative

by Ernest Adams

What makes a computer game replayable? And why are some replayable and some not?

In principle, any game should be replayable. If you went down to the toy store, bought a board game in a box for twenty or thirty dollars, and then came home to discover that you could only play it once, you would be rightfully wrathful. Yet, this happens fairly frequently with computer games, and our customers are more or less resigned to it. Replayability, however, is no accident: it’s something we as designers can build in on purpose…if we want to.

Let’s start with the question of whether we want to. From a purely mercenary standpoint, replayability isn’t always a good thing. If a game is endlessly replayable, our customers have no reason to go buy another game. We need them to buy new games to keep ourselves employed, so we have a financial motive to build a certain lifespan into our games. However, I don’t know of any developer who actually feels this way. For one thing, most games already have a certain lifespan because of galloping technology; there’s no need to build one in artificially when Intel and AMD are doing their best to make sure our games are obsolete in a couple of years no matter what we do. But more importantly, most of us have some creative pride. We want people to go on playing our games for a long time. We respect games, like Civilization and Myst, which people continue to play for years, and we respect their designers for having achieved such a thing.

So assuming that we do want to make a game replayable, what issues influence replayability? Leaving aside technology, which we can’t control, how do we design a replayable game? In the first part of this article, I’ll address the effect of narrative on games, and in the second part, I’ll look at game mechanics.

Narrative in games – that is, the storyline, when there is one – tends to be fairly fixed and fairly linear. Despite 25-odd years of more or less haphazard research, no one has devised a really satisfactory “branching storyline.” When people replay the game to see branches that they missed the first time, they tend to hurry through those parts that they’ve already seen, paying little attention. And if the narrative is linear, as in Starcraft or Diablo, once you know the story, it doesn’t provide much motivation to play the game again. Fortunately, those games offer sufficiently interesting gameplay that they’re worth playing again even if you already know the story. But for adventure games, the story is most of the reason for playing them. Once you’ve solved all the puzzles and you know the whole story, there’s little reason to do it again. The more important narrative is to a game, the more of a disincentive it is to play it again.

But I don’t think it has to be that way.

If you drive to the far northern tip of Scotland, where puffins nest among the sea-cliffs and the mist swirls over the grass even in high summer, you can stand and look north across the treacherous waters of the Pentland Firth to a low, treeless archipelago: the Orkney Islands.And if you take the ferry over to the Orkneys, you can visit dozens of ancient stone monuments left by people hardier than we: Neolithic farmers, Picts, Vikings. Among them is a beautifully preserved little village, Skara Brae, where all the walls, floors, and even furniture are made of flagstones. Nowadays you can stand on the wall-tops, look down into the roofless rooms with their beds and shelves and cupboards all of stone, and try to imagine what it must have been like during the icy howling darkness of a North Sea winter’s night, five thousand years ago. People dressed in skins, huddling around the hearth in the reeking gloom, burning such driftwood as they could find, the only light coming from the fire.

How did they pass those endless winters? Working, certainly: cooking, sewing, tending babies and mending tools. Playing, certainly: singing, talking, telling jokes and laughing. Doing what humans do: eating and sleeping, making love and giving birth, falling ill and dying. And throughout it all, the thread that spans the generations: telling tales and listening to them told.

Nowadays we have so many stories to choose from that a man could spend his entire life reading, watching television, going to the movies all day, every day, and never once hear the same story again if he did not want to. But in ancient times, the tales were fewer, and memorized, not written down. Perhaps their telling was the province of a privileged group, or even a single person: the bard, the singer. And so by the time she had reached old age – that is to say, her fifties, if she survived childbirth – a woman must have heard the same tale many a hundred times.

Why did they bother? Why did they care? Was it because any story, no matter how many times heard, was better than silence? I doubt it. In silence inheres the potential for all stories, good and bad; in speech, the potential becomes the real. It is better to hear only silence than to hear a bad story told again. I believe the reason our ancestors listened to the same stories again and again was that they were good stories.

With so many tales to choose from, we now assume that once we know the plot there’s no longer any point in hearing the story again. This is true for most of our stories: is any given episode of Kojak or 21 Jump Street that worth seeing a second time? Probably not. But there are a few tales that we do see, or hear, or read over and over. We drag out A Christmas Carol year after year, and even if Tiny Tim is too saccharine for modern tastes, the story of a bitter old man’s redemption is not.

I usually re-read The Lord of the Rings, or parts of it, about every 18 months. I know it backwards and forwards. I know I’m not going to learn anything new about the plot. What brings me back, what keeps my attention, is not the tale but the telling.

Consider the following sentence from near the end of the book. It occurs at the penultimate moment, when Frodo is standing at the Cracks of Doom with the Ring in his hand. The Dark Lord has suddenly become aware of him, and knows that his very existence hangs by a thread.

From all his policies and webs of fear and treachery, from all his stratagems and wars his mind shook free; and throughout his realm a tremor ran, his slaves quailed, and his armies halted, and his captains suddenly steerless, bereft of will, wavered and despaired.

Read aloud, this sentence rings with the rhythms of poetry. The first two phrases have a parallel construction, and in fact, they are perfect iambic heptameter and hexameter respectively:

From all / his pol- / i-cies / and webs / of fear / and trea- / cher-y

From all / his stra- / ta-gems / and wars / his mind / shook free

They even rhyme. The next phrase sounds like Anglo-Saxon alliterative verse, with its repeating initial consonants:

and Throughout his Realm / a Tremor Ran

and with the exception of the word “and,” it too is composed of iambs:

through-out / his realm / a tre- / mor ran

Then we return to parallel construction with “his slaves quailed, and his armies halted.” After that the rhythm begins to break up, just as the Dark Lord’s regimented, mechanized world began to break up. Did Tolkien do this deliberately? There’s no way to tell, but he was a poet who knew everything there was to know about the English language, and consciously or unconsciously, his mind used that knowledge to work his material. At a moment in the story when only poetry could do justice to his vision, he employed its methods to great effect. This is one of the most powerful sentences in the book, but it’s the kind of thing you only notice on a second, or third, or twelfth reading.

Telling a Great Tale

To appreciate great stories it isn’t necessary that they be new. People go to the opera with a full knowledge of the plot, and indeed the plots of most operas are pretty thin. What they go for is the performance, the power and beauty of the human voice. Why did teenaged girls go back to see Titanic again and again and again? They already knew the plot. It was because of the way it made them feel, and that, too, is a function not only of the tale but the telling.

Some time ago, I began wondering how to think about comic books – their stories go on and on, and their heroes and villains never grow old and seldom die. They suffer setbacks from time to time, but few of these changes are permanent. The stories are presented as if they are part of a continuous narrative, but of course that makes no sense; it means that Batman, a normal human being, has been fighting crime continuously for nearly seventy years. To what class of literature do comic books belong? Finally, I concluded that they are not novels, not serials or soap operas, but legends. Legends don’t have to hang together to form a coherent whole. There can be an infinite number of stories about Paul Bunyan, and he never grows old or dies, because each tale is self-contained.

Titanic offered viewers an emotional resonance that goes beyond the plot alone.

The publishers of comic books are afraid to kill a character, for fear that people will expect him to remain dead forever. They invent origins for their characters, and they have ongoing stories of their adventures, but they don’t dare tell how they die. They’re still hung up on this idea that their books are continuous narratives. At least, they were until 1986.

In 1986, Frank Miller wrote a graphic novel called The Dark Knight Returns. In this book, he told the tale of Batman’s final battle and his end. He recognized that the readers of comic books are not necessarily small children; that they are mature enough to be able to read the story of Batman’s doom without assuming that the publication of other Batman stories must therefore cease. In his introduction to the book, Alan Moore wrote:

All of our best and oldest legends recognize that time passes and that people grow old and die. The legend of Robin Hood would not be complete without the final blind arrow shot to determine the site of his grave. The Norse Legends would lose much of their power were it not for the knowledge of an eventual Ragnarok, as would the story of Davy Crockett without the existence of an Alamo.

In providing a capstone to Batman’s career, Miller took nothing away and did nothing to obstruct the creation of further legends. He simply gave it a fitting end, one without which the legend was incomplete.

Another thing about legends is that it isn’t necessary for them to be consistent. We know they’re fiction, not fact. There’s no reason why one particular version of Batman’s fate must be definitive. In composing The Ring of the Nibelung, Richard Wagner substantially re-wrote the Norse legends for his own purposes, and while the results are not “true” to his source material, his source material isn’t “true” to anything either. He was working from copies of the legends written down in medieval times, by authors who themselves chose to record one particular version of far more ancient oral tales. In a more modern example, the author John Fowles was unable to decide on an ending for The French Lieutenant’s Woman, so he unapologetically created two different endings and told them both.

These, I think, are the keys to making a narrative game replayable. First, if the story is linear, to make it so good that it’s worth hearing again and again, even if we know the plot. To do as Tolkien did, and write it well; to do as opera does, and perform it well; to do as Titanic did, and offer an emotional resonance that goes beyond the plot alone. To tell the tale as the Stone Age singer told it on a North Sea winter’s night, so spellbindingly that your audience can hear it a hundred times without tiring of it. That’s a tall order, but it can be done if we find the right talent and make the commitment to do so.

In composing The Ring of the Nibelung, Richard Wagner substantially re-wrote the Norse legends for his own purposes.

Second, to treat our stories not as collections of fixed immutable facts that accurately record a “history” that never happened, but as legends that speak of mighty heroes, great events and deeds. People have spilled gallons of ink arguing about minute inconsistencies in the Star Trek universe; a few decades ago, they did the same over the Sherlock Holmes stories. That’s because they’re treating these fictitious worlds as if they were objective reality. There’s no harm in letting them enjoy themselves in this manner, but we should be wary of doing so ourselves. For us as designers to bind ourselves to a single version of events in our worlds is to tie our hands creatively and make it much more difficult to make a game replayable. Replaying a game creates variation, and variation demands narratives that are tolerant of it. Tales, not “truth.”(source:gamasutra)

上一篇:分析游戏重玩性之机制篇(2)

下一篇:论游戏设计师在当今行业中的地位

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号