新的游戏生产模式带给开发者的挑战和机遇

作者:Jedrzej Czarnota

随着玩家人数的增多,新的游戏生产模式也随之产生。在本文,我们将一起探究这些新模式将如何重塑旧的行业体系。

改变宏观经济环境

毫无疑问,玩家的激增正在改变游戏的生产、发行和推广方式(更别说游戏本身的商业模式)。但更重要的是,诸如众筹这种更加公共性的生产模式,正在重塑游戏开发者和玩家之间的关系。这一方面使玩家的权力更多了,另一方面使开发者能够接触到更多小众市场。这些变化受到许多人的欢迎,被认为是游戏开发摆脱一些与大发行商有关的恶劣的游戏生产和营销模式的标志,是行为的创新文化的复兴(但因为发行商的风险规避和对旧游戏的依赖,这股风气又被削弱了),创造了新市场和培养了新的玩家类型,给开发者更多与发行商谈判的筹码,允许更多艺术(和独立)项目诞生等等。

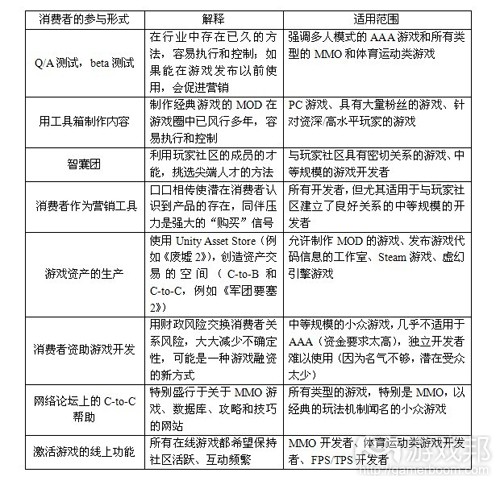

似乎数字游戏行业的宏观经济本身也在逐渐演变。原因不只是在线推广的兴起,更重要的是,游戏行业越来越依赖玩家在游戏生产中的参与。这种参与表现为多种形式—-如下表所示。这些趋势与更广阔的现象相结合,主宰了这整个媒体行业(例如,广播行业)—-越来越强调开发者与受众协作生产。说到游戏生产,游戏开发的经典的阶段模式一直被认为效率低下(不同的游戏开发工作室已经不同程度地用敏捷开发法取代旧模式),但因为那些最近的变化,我们应该会看到那些仍然存在于游戏开发中的模式将逐渐被抛弃。

注:有些消费者参与游戏生产和后期制作的形式可以归类到“联合创作”名下。注意,这在中等预算的游戏和MMO游戏中表现得最明显。

那些现象可以统一归类为数字游戏的“联合创作”。它们表现为多种形式,不同程度地出现在游戏开发公司(或游戏发行公司—-这是另一个话题,因为区别太大,我们就不在这里讨论了)。它们不只是发生在游戏产生的三大方面—-设计、技术(代码和编程、游戏引擎等)和内容(美术资产、动画、模型、声音、音乐等)中。关键是,消费者联合创作不一定只能与游戏本身相结合。消费者,因为前期/后期过程的参与的变化,可以参与到游戏开发和生产的公司运营方面(组织、商业模式、营销、价值链、推广。等等)。最好的案例就是通过众筹,允许消费者资助游戏开发;在“旧的”模式中,消费者是不可能接触到游戏开发的,而今天,因为消费者关系和社区管理,新的模式已经形成一定的规模。在这个新的“开放”的模式中,公司开始因为消费者资助产品开发、服务和运营(游戏邦注:游戏既是产品也是服务,服务属性主要体现在游戏发布后的阶段,这时工作室要发布补丁、新内容、建设玩家社区、组织比赛等)而受益。

毕竟,“两个脑袋比一个聪明,三个就更聪明”。无论是什么行业,消费者也具有产品或服务相关的能力,意味着在消费者当中,一定会有许多领域的专家,包括这个生产过程本身的领域。游戏开发者已经见识到消费者的能力了—-玩家帮助找漏洞、制作新美术资产甚至大力帮助社区建设和游戏推广—-他们确实非常有才能,毕竟这些活动都需要很高的技能水平(有些甚至相当于游戏开发公司的雇员)。关于开放创新模式的理论指出,只要社区足够大,那么这个社区就可能存在任何领域的人才;游戏,甚至“非AAA级”游戏,有非常多的粉丝。在这个基础之上,那些粉丝聚集起来成为管理透明、交流渠道畅达的社区。据此,我们可以进一步推论,游戏玩家社区是开发者的强大资源,可以帮助开发者解决所有可能的问题,因为社区成员当中总是存在那些领域的专家。

主人还是管家?

当然,这么乐观的想法可能会让一些读者疑问“那么我们还需要游戏开发者吗?”和“显然,如果玩家社区自己就能做出游戏,那么我们就不需要游戏开发公司了!”确实,高水平的消费者参与自己擅长的领域的职业人员竞争这一现象,已经出现在文学圈。理论上说,各种公司都可以把自己的工作外包给从消费者和粉丝中招募来的外部合约工作者。尽管如此,在游戏开发中实践和成功的执行这种商业模式会带来许多挑战,现在还不适用于任何中等规模及以上的游戏开发公司。但我们唯一可以保证的就是,在未来,这种模式并非不可能成真。

就行业现在的状况,上述两种情况都是完全不可能的。游戏开发者的职责绝不只是找到知道怎么做游戏的人来做新游戏。游戏开发工作室的角色仍然是不可或缺的:它们提供结构、组织、商业头脑,能够应付险恶残酷的免费市场环境……像游戏开发工作室这样的组织有自己的“额外价值”,绝不只是部分(各个员工)组成的整体。它们也是市场可行性的审判员,且多亏了它们的层级化和中央集权化的结构,他们能够成功地对市场做出反应(比如,发现消费者的需求)。知道应该制作和发布什么样的游戏不是一件容易的事—-消费者的需求很难确定,特别是对于创意行业,消费者的许多强烈需求在商业和生产上是完全不可行的。

新机遇

在缓慢重整的数字游戏行业,这正是游戏开发工作室的新机遇。如果游戏开发者想从市场(特别是从仍然比较小众的联合创作市场)获得最大的剩余价值,他们应该成为创意的过滤器。他们应该学习(除了重新培训游戏开发技能之外)如何引导、利用和选择消费者的创作,这样他们的游戏生产过程才能因加入玩家的创造而得到强化(而不是被破坏!)。另外,如果消费者不仅可以联合创作游戏,而且能够参与游戏开发公司的其他方面的工作,也许数字游戏工作室可以开始招募那些并非他们的游戏的受众但想从事营销(比如)的人来联合创作?众筹就是一个例子—-并非所有“花大钱”的赞助者都对正在众筹的产品/服务感兴趣,他们有些人其实是为了扩展自己的行业人脉、想了解个社区,或者丰富自己的投资阅历。游戏开发者应该放开眼界,不要单纯地以为“靠玩家修复漏洞和玩家的联合创作得到新的美术模型,未来将属于这些工作室—-能够创造新的游戏生产模式和利用消费者的工作室。”

注意,联合创作的消费者并不是游戏行业(或任何其他行业)的不竭资源。他们本质上还是有自己的正常工作的一般人,他们只是利用自己的空闲时间进行联合创作。他们的时间和精力是非常有限的。

众筹:破坏的先锋?

那就是为什么我们会看到那么多众筹的PC游戏项目。与主机游戏或休闲手机游戏相比,PC游戏总是有更多虔诚的玩家。PC游戏市场中还有小众玩家等着开发者去开发—-最典型的例子就是经典的等角RPG或日式RPG。那些小众市场也可能被更新奇或实验性玩法的游戏(比如《Godus》、《Planetary Annihilation》)或跨类型的游戏所占领(对这个话题感兴趣的读者,我建议你们去看看Steam游戏和Steam Greenlight项目,有很多这类游戏虽然还在开发,但已经在主页推荐了)。那些小众市场的存在解释了为什么PC游戏公司往往能在游戏开发环节和经营的其他方面的联合创作中获得最大好处。他们已经与品味相当统一的消费者社区建立密切的关系。此外,因为开发这些游戏需要的资金规模,那些工作室和他们的生产被划归类到中等预算的游戏市场。他们占据小众市场表明,那些游戏开发者在寻找新的竞争优势方面,占据了最佳位置,超过了老牌公司如大发行工作室。这个优势反映为,在建设社区和分摊游戏开发风险以及延长价值链方面,那些中等规模的工作室有表现得更加敏捷和熟练。另一方面,这是高度重视风险规避和不确定性的AAA工作室所不能享服的奢侈(因为财政风险意味着失败,或害怕产品销量不佳)。开拓性市场和行业变化催生了新的“商业游戏”的环境和规则,将为正在占领小众市场的工作室取代(越来越不能应对变化的)AAA级发行公司创造条件。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Developers – your role in the coming war, and the ways you can benefit from new modes of game production.

by Jedrzej Czarnota

Welcome back, commander! In today’s article, your very survival is at stake… We are here to discuss new modes of production in digital games brought about by the increasing role of customers, and how they can restructure the currently existing industrial regimes.

Changing macro-economic environment

There is no doubt that customers’ relentless march is changing something about how the games are produced, published and distributed (not mentioning the business models of game development studios making them). More importantly still, by the very public manifestations of it, such as crowdfunding, the relationship that exists between game makers and game players is becoming reframed. The latter are empowered, and for the former numerous market niches become available for business – niches where devoted customers’ following exists in the form of communities. These changes by many are hailed as the much-desired breakoff from some of the bad things that are associated with the big publisher mode of game production and marketing. They are seen as reinvigorating creativity in the industry (recently eroding due to big publishers’ risk aversion and reliance on established IP franchises), opening new markets and customer groups for gameplay, giving game developers more power in negotiations with investors, allowing more artistic (and indie) projects to see the light of day, and many more…

It seems that the macro-economic environment itself of the digital games industry is gradually changing. Not only the rise of online distribution is causing this – but most of all, the increasing reliance of game industry on the creativity and involvement of players in games production. This involvement can take many forms – let us look at them briefly in the Table 1. Those trends are coupled with wider phenomena becoming dominant in the media industries overall (for example broadcasting industry) – which are becoming increasingly focused on co-terminous and co-located preproduction, production and postproduction. The classical milestone mode of games development has long been shown as inefficient when it comes to game production (and has been, to various extent in different game development studios, replaced by Agile or Scrum approaches), but with those recent changes we should see complete abandonment of those still lingering takes on game making.

Table 1. Some of the forms of customers’ involvement in digital games production and postproduction, which can be grouped under the term of ‘co-creation’. Notice the prevalence of mid-budget games and MMO games as loci of those phenomena.

Those phenomena can be collectively classified as ‘co-creation’ of digital games. They take many forms and have many dimensions across game development firm (or game publisher firm – but that is a topic for another article, as there will be some significant differences which we have no room to discuss here). They can occur not only in the three classical aspects of game production – namely design, technology (i.e. code and programming, game engine etc.) and content (i.e. art assets, animations, models, sounds, music etc.). The point here is, that customer co-creation does not have to pertain only to the game itself anymore (understood here as the playable cultural artefact and object of fan-like following). Customers, due to changes in back/front-stage processes can get involved in the firm (organizational, business model, marketing, value chain, distribution etc.) aspects of the game development and production. The best example of that is the opening of game investment to customers by crowdfunding; in the ‘old’ model it used to be the domain of game development completely hidden from the customers, while today it is out there in the customer relationship and community management spheres. In this new ‘open’ paradigm, firms are beginning to be in the position of benefiting from having their customers engaged with their product, service, as well as operations (games are both products and services; main manifestation of service-like nature of games is in the post-launch phase, where studios will patch games, release new content, engage with the community, organize contests etc.).

After all, ‘two heads is smarter than one, and three is even better’. It is true for any industry that customers also have product or service-related competencies, meaning that among customers there will be experts in many domains, including the domain of the production itself. Game developers are already experiencing this – having their players help them with bugs, making new art assets, and even significantly helping with community development and game marketing – and they readily tap into those activities which after all require high skills (in some cases comparable to those of actual game development firm employees). There are theories in the academic literature on open innovation paradigm, that any kind of competence will be always hosted in the community of customers if that community is large enough; and games, even the ‘not-AAA’ titles, have very big fan followings. On top of that, those fan followings are well organized in communities and are characterized by transparent to the firm and traceable communication channels. From this statement further conclusions are obvious – the community of game players is a powerful resource which potentially has the capacity to help game developer with any possible problem, as the community will have members who are already expert in those domains.

Ni Dieu, Ni Maitre?

Of course, this optimistic vision could cause some of the readers to ask “Why do we need the game developers anymore then?”, and “Surely, if we have all the competencies in our community to make a game already, then let’s make it without the firm!” Actually, the risk of having skilled customers competing with and displacing professionals in their domains is a valid scenario in academic literature (Wexler, 2010). Theoretically, all kinds of firms could become nexi of social outsourcing networks, with all work done by external contractors recruited from among customers and fans. Nevertheless, realization and successful execution of such a business model in games development would pose numerous challenges, and would not work today for any mid-size to large game production enterprise. The only thing we can say, though, is that such a scenario is not an impossible one to appear in the future.

For the current state of the industry, both of the sentences above are completely false. Game developers have functions other than just loose amoebas of skilled people who know how to do things to make new games. The role of game development studios is still indispensable: they provide structure, organization, business acumen, are capable of navigating the treacherous and aggressive environment of free-market economy… Organizations such as game development studios have their ‘added value’ and are more than just a sum of its parts (as represented by competencies of individual employees). They are also judges of market feasibility, and thanks to their hierarchical and centralized power structure are capable of successfully responding to the market (in terms of, for example, realizing customer needs). Understanding what kind of game to produce and launch is not an easy thing – customers’ needs are difficult for firms to gauge, demand uncertainty in the creative industries is high, and many of the customers’ most heartfelt wishes are completely commercially and production-wise infeasible.

New opportunities: arise!

Exactly here is where game development studios’ new functions, and the new opportunities for them in the slowly reforming digital games industry, are. Game developers, if they want to be poised for maximum extraction of surplus value from the market (and especially from the still vastly dormant market of customers’ co-creation), they should become filters of ideas. They should learn (apart from retaining their game development competencies) how to induce, harness and then select for the creativity of their customers, so that their game production process is enhanced and empowered (and not disrupted!) by their players’ creativity. Furthermore, if customers can co-create not only games but can also become involved in other aspects of game development firm, perhaps digital games studios could start recruiting people to co-create who are not players of their games at all, but who for example just want to get engaged in marketing instead? We have already seen it in the case of crowdfunding – not all ‘big dollar’ backers are interested in the product/service being crowdfunded – some of them are seeking to build their professional networks, get access to certain communities, or do it as part of their investment portfolio. Game developers should think large and beyond just simple ‘players of our games fixing our bugs and making new art’ model of co-creation. The future will belong to those studios, which will innovate in the new modes of game production using their customers.

One thing to remember here, though, is the fact that co-creating customers are not an infinite resource in the digital games industry (or any other industry for that matter). They are essentially normal people with normal jobs, who only use their spare cycles to co-create. Their time and attention will become one of the scarce resources that industry actors will soon start competing for.

Crowdfunding: vanguard of destruction?

Figure 1. Colossi of the world… Behold the agent of your demise!

That is also why we are seeing so much crowdfunding in the PC sector of the industry. PC games have always had more devoted following of players than mass market console games or more casual-natured handheld and mobile games. Niches exist within PC gaming market for the game developers to occupy – the best examples of which are the classical isometric RPGs or JRPGs. Those niches can also be occupied by games with more innovative or experimental gameplay models (Godus, Planetary Annihilation) or bridging across various genres (to readers interested in this topic, as well as those pursuing more examples of games like that, I recommend a visit to Steam and Steam Greenlight, where more and more games which are still in development feature prominently on the front page). The presence of those niches is the reason why PC gaming firms are poised particularly well to benefit most from the process of co-creation in their game development, as well as in other aspects of their operations. They already have close relationship with well-defined and fairly taste-uniform community of customers. Moreover, due to the size of investment required to develop such games, those studios and their productions are placed in the mid-budget game market. That and their occupation of niches suggest that those game developers are in the best position for seeking innovative competitive advantages over the established (incumbent) firms, such as big publisher studios. This advantage is reflected by the fact, that those mid-sized studios have agility and manoeuvre space in terms of how they engage with the community and how they spread the risk across the process of game production as well as value chain location. This, on the other hand, is a luxury that extremely risk-averse, high-demand-uncertainty operating triple AAA studios simply do not have (as the financial risks associated with failed, or even under-selling products are too large). This is a textbook position for the ground-breaking market and industry change, one in which new conditions and rules of the ‘business game’ will allow the studios currently occupying niches to successfully displace (increasingly vulnerable to change) AAA publisher firms. (source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号