解析动作冒险游戏的关卡设计要求(二)

作者:Toby gard

到上篇文章描述的进度时,你应该有一些纸上地图、写好的故事、详细的流程图、概念美术和3D空间模型了,这些取决于关卡团队的偏好关卡计划。

那些关卡具有令人惊奇的外观。我认为应该笔直的动作关卡可能具有许多令人困惑的小通道,许多关卡可能提示超出当前关卡的想法。

评估整体情况

为了组织他们的反馈,创意主管必须评估大气层有关卡计划。因为关卡可能非常复杂,所以最好能制作一个整个游戏的简化展示版,这样你就可以估计体验的节奏和情感氛围的一致性了。

提取机制

第一步是确关卡团队相屋的所有这些特例,并更新关卡计划。不可避免的,有些特例可能非常不错:

Ken Kong落入30层的电梯竖井,他在半空中施展功夫,直到他身下的僵尸尸体堆得足够高时,他就是站在尸堆上,免于死亡。

这听起来很了不得,但这个战斗系统不可能容纳这种“下落战斗”机制,所以关卡团队认为应该做成过场动画。

在许多其他关卡中,Ken Kong必须破坏一些墙体,关卡团队提议加入不同的McGuffin(游戏邦注:这是书、电影中用来推动情节发展的对象或事件)使他能做到,比如允许他使用身边的一个不平衡的重物来破坏墙体。

正这这一系列想法产生了精致原创的游戏机制,进而使你的项目与其他人的区别开来。通过促进具有灵活性、可以扩展到核心机制中的想法,我们可以制作出更丰富、更连贯的体验。

例如:

破坏墙体如何成为可重复使用的机制?是否需要消耗品,或是现成的技能?升级这种技能需要什么条件?它与其他玩家能力是否产生协同作用。

假设,我们可以把破坏墙体与新幸存者类型——一个爆破专家相结合。这个家伙随身带着一种具有多种用途的炸弹,但当他被僵尸攻击时,他就会引爆炸弹——可能对你自己一方造成很大伤害。可以用一些标准的“炸弹携带者”和/或可以用于若干关卡的敌人,做成一种有趣的风险/奖励机制。

也许这种“下落点头”还可以用在几个关卡中,但看起来更像迷你游戏,而不是新机制。虽然这个想法有趣,但问题是,你能把这种玩法做出足够的深度,使整个游戏中接连出现三四次“下落战斗”变得合情合理吗?这似乎像是大投入换小成果,但如果我们能做成,效果应该会相当不错。

这些机制通常,因为它们不是出于根据竞争产品的盒子标记而被强制放在游戏设计中的,而是通过探究它的独特主题和深入探索它的世界而被有组织地发现的。

如果我们已经把新机制整合起来,并且驳回或注意到所有新设置,我们就可以让合适的角色融入这个定义得更加清楚的世界中,收集必须反馈给关卡团队的主要信息。

玩法类型

大部分游戏都会混合使用元素。例如,FPS可能包含70%的行走射击和30%的交通工具战斗。

如果游戏中的所有关卡具有完全相同的玩法混合模式,那么玩家很快就会觉得无聊。但如果绝大部分关卡要求玩家行走,再用少数几个允许使用交通工具的关卡作为点缀,那么就会使整个体验更新鲜,从而保持玩家的兴趣。

通过检查游戏过程的玩法类型混合,你可以找出体验太过平淡的地方。

一款持续保持玩家兴趣的游戏的例子就是《半条命2》。几乎第一个关卡都有新的操作主题,比如新武器、新交通工具或新敌人,玩家体验大约每30分钟就会发生一次明显的变化。

案例:《Kung Fu Zombie Killer》

我们以幻想游戏《Kung Fu Zombie Killer》为例,详细地分析一下你所拯救的幸存者类型对它的玩法变化的影响。

医生,你可以设计这样一个关卡,要求玩家医治受伤的幸存者。

叉车司机,你可以设计这样一个关卡,要求玩家把重物运送到某个地点。

工程师,你可以设计一个带有传统的谜题元素的关卡。

战士,在这个关卡里,你的战士伙伴贡献了大部分的战斗力。

……

我们假设以下地点就是关卡的场景:

道场

医院

建筑工地

军事基地

发电站

警局

超市

市政厅

大学校园

电影院

电视台

办公大楼

我们从故事中可知,游戏必须从Ken所在的道场开始,在Ken救jenna126xyz的电影院结束。

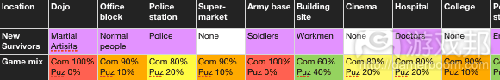

我们的游戏目标中有80%是战斗,20%是谜题,排列如下:

但在细节化阶段,有两件事发生了。(发生变化的事可能更多,但我们在这里只简单地说两件事)

首先,有人想到可以在幸存者类型中加入教师,教师可以通过讲课使僵尸入睡,这就改变了大学校园中的玩法,加入更多谜题元素。

第二,有人提议把电影院改进电影工作室,这样僵尸和幸存者就可以根据像西部片或哥拉斯之类的老套电影来安排了。大家对这个想法感到兴奋,并据此想到了一些非常疯狂的机制,足以把这个场景分成两个关卡。

结果,我们就看到以下有点儿不平衡的玩法,且关卡太多了:

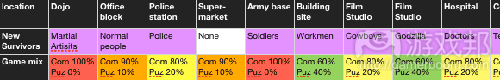

我们想到的机制数量很多,几乎足够给每一个关卡分配一个新机制。我们调整了关卡,即删除超市和把发电场往前移,做出了更好的玩法节奏:

仍然有改进的空间;我们可以给市政厅关卡中加入新的生存者类型,也可以换成其他东西。

情绪图

在游戏过程中,你想让玩家体验到各种情绪。主角可能经历暗恋、复仇、悲伤和愤怒,等等。这些情绪性事件是值得追踪的,但不如整体情绪基调或者你希望玩家体验到的情绪那么重要。

我所谓的“情绪”的概念是,可以传达给玩家的基本情绪。所以,惊慌、害怕、恐惧、敬畏和兴奋就属于这一类,而更高级的概念上的情绪主题如复仇、嫉妒或虚无主义就不属于这一类。

生成情绪图有两个目的。除了用于评估关卡顺序和内容是否与玩家的情绪历程产生互动作用,更重要的是,作为使整个开发团队一致地以创造整体体验为目标的基本工具。

例如,假设Ken Kong经历的故事是这样的:

Ken在城中一路战斗,为了拯救自己心爱的人,但战斗拖延他太久了,当他终于见到她时,她已经变成僵尸了。

如果我把情绪如表示如下:

笨拙-闹剧-渐强的欢喜-彻底的喜剧

1、美术风格必须是明快的

2、动画通常是夸张的、风格化的

3、音乐和声音往往是快节奏的,滑稽的

4、UI元素可以设计得随意一些

通过准确地定义情绪,可以引导整个团队朝着你想要的方向设计和制作。例如,“渐强的欢喜”意味着基调渐强,也就是音乐强度走高,动画更加夸张,节奏更加欢快。

虽然你可能以为《Kung Fu Zombie Killer》的基调可能被定义为“滑稽的”,但它的表述对整个开发过程具有重大影响。

例如,如果我把整个游戏的情绪图如定义如下:

惊慌-恐惧-越来越惊恐-悲剧

游戏中的方方面面都会被这个情绪图完全改变:

1、场景更昏暗,关卡的光源是闪烁不定的,剧情令人越来越不安。

2、动画往往是写实的,且避免任何可能显得可笑的动作出现。

3、音乐和声音效果会令人感到焦虑。

4、UI元素偏向写实风格,且不显眼。

相同的游戏设计,但两种情绪图产生了完全不同的游戏体验。当整个团队都接受这种情绪图,并且认真地把它融入他们制作的每一个元素和每一个决定中,那么这些情绪就能成功地传达给玩家。

但是,通常情况是,游戏应该传达什么样的情绪或基调、玩家在某个时刻应该体验什么样的情绪,团队中的各名成员对此的理解都会稍稍不同。所以,当开发团队每个成员都在游戏中传达稍有不同的情绪信息时,为什么那么多游戏都不能感动玩家,也就不足为奇了。

情绪图可以是如上述那么简单的四个阶段,或者也可以详细地把若干情绪片段放进各个关卡中。记住,没有剧情的故事基本上只有一种情绪,而恐怖游戏通常在渐强的紧张和彻底恐慌之间起伏振荡。

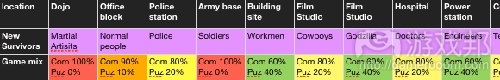

当你的玩法类型和情绪图都确定后,你应该看到如下关卡计划:

在我们的案例中,我们的游戏后期有节奏较慢的谜题关卡,我们希望玩家在那些关卡中体验“渐强的欢喜”。通过重新调整关卡顺序,或把一个关卡的设想转移给另一个关卡,可以使情绪目标更加突出:

幸运地是,《Kung Fu Zombie Killer》的关卡顺序是非常灵活的,但大部分游戏并不是如此。在某些情况下,答案是,反馈给关卡团队,指导他们如何把情绪和玩法更好地融合起来。

虽然以上例子可能不是最好的顺序,或最好的情绪图,但我要表达的重点是,迫使自己检验整个计划,以便根据各个关卡在整体体验中的地位给出反馈。

网格模型和原型

下一步是在3D软件中制作关卡模型。我建议这一步由美工来做,而不是设计师,如果你希望做出来的空间是可信有趣的话。应该用网格模型验证计划的关卡在当前的技术和生产条件下,是否能达到理想的效果。

因为这些关卡是原型,所以最终效果必然会与计划稍有出路。在整个模型和原型阶段,设计师应该根据美工修改计划,主管必须不断更新游戏进度表,并且确认关卡与情绪图的情境相符。

通过继续抽取从网格模型阶段产生的新机制,并做好随时再次准备调整关卡顺序,你可以在不约束关卡制作人员的创意的情况下使游戏市场计划保持平衡。

最后的计划

通过构建网格模型而获得的信息应该能明显地改进游戏设计。

最后的情绪图将体现所有资源创作。

新机制已明确并插入所有相关关卡中。

关卡已重新排序并产生理想的节奏和情绪。

薄弱关卡计划已被删除。

玩家技能已做出原型,并定义了最后的指标。

一旦所有关卡的原型都做完了,那么已经修饰好的关卡就可以作为样本,给制作阶段提供非常扎实的基础。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Action Adventure Level Design: Pacing, Content, and Mood

by Toby gard

By the end of the process described in the last article — building through fiction — you will most likely have a mixture of paper maps, written stories, detailed flowcharts, concept art and possibly some 3D mockup spaces, depending on how each level team prefers (or has been instructed) to represent their plan.

Those levels will have taken shape in surprising and unexpected ways. Levels that we had assumed to be straightforward action levels may have revealed rich veins for puzzles, and many levels are likely to have prompted ideas that fall outside of the current game mechanics.

Evaluating the Big Picture

To structure their feedback, the creative leads need to validate all level plans in relation to each other. Because the levels are likely to be pretty complex, it is useful to create a simplified representation of the whole game so that you can assess the pacing and emotional consistency of the experience.

Extraction of Mechanics

The first step we need to take is to identify all of these special case interactions and ideas that the level teams have come up with while fleshing out the level plans. Inevitably they will be some of the coolest in the game:

Ken Kong falls down a 30 story lift shaft, doing frantic mid-air kung-fu until there is a pile of zombie bodies beneath him thick enough for him to survive the drop.

It sounds awesome, but the fight system simply cannot accommodate this “fall fighting” mechanic, so the level team has suggested it as a cutscene.

In a couple of other levels, Ken Kong has to destroy some walls and the level teams have proposed different McGuffins to allow him to do this, such as a convenient, precariously balanced heavy object that will break through the wall if triggered.

It is this list of ideas that can produce the neat and original game mechanics that will set your project apart from everyone else’s. By promoting ideas that have the flexibility to be expanded into the core mechanics and peppering them throughout the game, we can create a richer more coherent overall experience.

For example:

How could destroying walls become a reusable mechanic? Would it require a consumable, or is it a readily available ability? How rich of a vein is it to be tapped for more applications? Does it have synergy with other player abilities?

Let’s say that we can integrate destroying walls with a new survivor type, a demolitions expert, who carries around explosives that can be put to all sorts of uses, but who also explodes when attacked by a zombie — potentially taking out a large proportion of your crowd. This could make for an interesting risk/reward mechanic and with some standard “explodable” barriers and/or enemies could be used in several levels.

Perhaps the “fall fighting” could also be used on several levels, but this seems more like a mini-game than a new mechanic. While the idea is interesting, the question is, could you make the gameplay deep enough to justify three or four “fall fighting” sequences throughout the game? It potentially seems like a large investment for too small a gain, but if we could make it work, it would be really cool.

These mechanics are generally gold, because they were not forced into the game design from a desire to tick boxes based on competitive products, but were discovered organically through an exploration of its unique themes and the thoughtful exploration of its world.

Once we have integrated the new mechanics and rejected or noted all the new set pieces, we will have adapted the character to live in this more clearly defined world and gathered a major part of the information needed to give feedback to the level teams.

Gameplay Types

Most games have a basic mixture of elements. For instance, an FPS might have 70 percent shooting on foot and 30 percent vehicle combat.

If every level in the game had exactly that mixture of gameplay, it would get dull for the player pretty quickly. But if you have levels that are entirely on foot, interspersed with a few levels that are predominantly or entirely involving vehicles, then they will act as palate cleansers, changing up the experience enough to keep players interested.

By looking at the mix of gameplay types over the course of the game, you can isolate points where the experience might be too flat.

A great example of a game that keeps the player constantly interested is Half-Life 2. Almost every level has a new central theme, whether it’s a new weapon, a new vehicle or a new type of enemy, your experience changes dramatically every thirty minutes or so.

Example: KFZK

Let’s carry on with the imaginary game Kung Fu Zombie Killer, discussed in depth the last installment. The variety of gameplay in that design comes from the types of survivors that you rescue.

With doctors, you could have a level where your goal is to heal injured survivors.

With forklift truck drivers, you could have a level where heavy equipment has to be taken to a particular location in order to progress.

With engineers, you could have levels that included traditional puzzle elements.

With soldiers, you could have a level where your crowd actually does most of the fighting for you.

And so on.

Let’s assume these were the locations we settled on for the levels:

Dojo

Hospital

Building site

Army base

Power station

Police station

Supermarket

Town hall

College campus

Cinema

TV station

Office block

We know from the story that the game has to start in Ken’s Dojo and that it has to end with camera men filming Ken as he rescues jenna126xyz.

We have goal mix of 80 percent fighting, 20 percent puzzles for the whole game and we had ordered things like this:

But during the detailing phase two things happened. (More likely a massive number of things would have changed, but let’s keep it relatively simple.)

First, someone came up with a really cool teacher survivor who can put zombies to sleep by lecturing them, which changes the gameplay mix at the college to involve more puzzles.

Second, someone has proposed changing the cinema into a film studio, whereby the zombies and the survivors can be based on clichés like Wild West or Godzilla films. People are very excited about this idea and enough crazy mechanics have come from it to justify potentially splitting it into two levels.

Consequently things are now looking a little less balanced and we have one too many levels:

(For full chart, please click on image)

We have found enough new mechanics that we can nearly introduce a new mechanic every level. By cutting the supermarket and moving the power station a bit earlier we can adjust the level order to create a better gameplay rhythm:

(For full chart, please click on image)

This can still be improved; we can look to either find a new survivor type that can be added to the town hall level, or we can try to replace it with something else that gives us more opportunities to do so.

Mood Map

There are potentially a host of emotions you will want the player to experience over the course of the game. The main character may experience things like unrequited love, revenge, sadness, and anger. These sorts of emotional events are important to track but they are not as important as the overall emotional tone or mood that you want the player to experience.

By “mood”, I mean a basic emotional concept that can be passed to the audience. So panic, fear, trepidation, awe, and excitement would be considered moods, while higher order conceptual emotional themes such as revenge, jealousy, or nihilism would not be.

Generating the mood map has two purposes. It is used to assess that the level order and content will not interfere with the emotional journey of the player but more critically it is a fundamental tool for aligning the whole development team towards creating a holistic experience.

For instance, let’s say that the story of Ken Kong will go like this:

Ken fights his way across the city saving the loved ones of his crush, but it takes him so long that by the end when he reaches her, she has been bitten and become a zombie herself.

If I define the mood map like this:

Kick-arse awesomeness – farcical chaos – mounting triumph – dark comedy

Art will keep things bright and well lit.

Animation will tend towards outrageous over the top stylized action.

Music and sound effects will tend towards fast-paced and comical.

Designers will feel free to be more game-y in UI game design decisions.

By defining the moods specifically over time you will guide the whole team more precisely than you might imagine. For instance “mounting triumph” implies a growing crescendo. It is likely to encourage a ratcheting up of music intensity, increasingly outrageous level end victory animations, and a general tendency to try to up the pacing each level.

While you probably assumed that the tone of KFZK would be defined as something like “zany”, the act of stating it over time has a dramatic impact on the whole development.

For instance, if I instead define the mood map for the whole game like this:

Panic – horror – increasing trepidation – tragedy

Every aspect of the game will be completely changed by this mood map:

Art will create darker dirtier spaces; they will light the levels with flickering pools of light and dress it with increasingly disturbing stories.

Animation will tend towards realism and will avoid any movements at might be construed as funny.

Music and sound effects will be disturbing.

Designers will try to keep UI and other design elements realistic and invisible.

With exactly the same game design, these two mood maps would generate utterly different gaming experiences. When the whole team embraces the mood map and diligently tries to express it in all the assets and creative decisions they make, the mood will be successfully instilled into the player.

What normally happens, though, is that every team member has a slightly different idea of what mood or tone the game should be creating, and rarely any idea at all of what mood the player should be experiencing at any given point in the game. Is it any surprise that most games fail to move people, when the development team are all communicating slightly different messages?

The mood map can be as simple as the above four stage progressions, or it can be as detailed as putting several mood chunks into each level. It is worth bearing in mind that literally no story-based game has only one mood. Even horror games oscillate between building tension and outright terror.

Once you have the gameplay types laid out and the moods defined you can see how the current level plans fit together.

(For full chart, please click on image)

In our case we have puzzle levels late in the game that are clearly going to slow the pace where we want people to be experiencing “mounting triumph.” By reordering levels, or shifting ideas from one level to another, we can better support the emotional goals:

(For full chart, please click on image)

Luckily KFZK’s level order is very flexible, but most games are not. In most cases the answer is to give feedback to the individual level teams to try to reach the desired mood and gameplay mix.

While the above example is probably not the best order, or even the best mood map, the point of the exercise is to try to force yourself into examining the entirety of the plan so that feedback on each level is given relative to its place in the whole experience.

Block Mesh and Prototype

The next step is to start building the levels in 3D, and I argue that the best people to do that are artists, not designers, if you want believable and interesting spaces. Block mesh should validate whether the level as planned will fit into the technical and production limitations while demonstrating that they can be compelling enough spaces.

As these levels are prototyped, inevitably things will end up being slightly different than planned. Designers will adapt their plans based on the art, so throughout the block mesh and prototype phase, the leads have to continually update the game rhythm chart and validate the levels within the context of the mood map.

By continuing to extract new mechanics that arise from the block mesh phase and staying open to level re-ordering you can continue towards a balanced game plan without restricting the creative process of the level builders.

Final plan

All the information gained by building the block mesh should have refined the game design significantly.

A final Mood Map has been created that will inform all asset creation.

New mechanics have been defined and inserted into all relevant levels.

Levels have been reordered and massaged to create the desired pace and mood.

Memory budgets have been validated.

Weak level plans have been cut.

Player abilities have all been prototyped and final metrics defined.

Once all the levels are prototyped and one level has been polished to act as a vertical slice, production can begin from a very solid basis.(source:gamasutra)

下一篇:你的手机游戏为什么失败了?

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号