阐述“学习游戏化”概念中的4个关键要素

作者:Dan Steer

在2013年美国培训与开发协会(ASTD2013)的W306座谈会上,教学设计师Julie Dirksen向我们介绍了“学习游戏化”的概念。

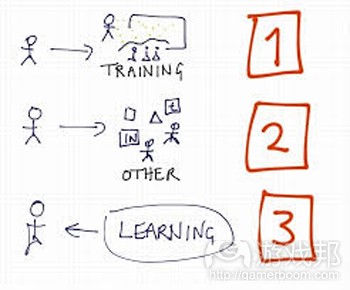

如果你像我一样,认为学习游戏化是值得探索的领域,那么你可能正在着手你的第一次游戏设计尝试。当你已经有了游戏的初步设想或知道如何把游戏机制与学习积极性相结合,那么你还需要什么才能让游戏成功?你应该遵循什么游戏设计原则?以下是Julie Dirksen的建议……

合理利用反馈机制

Dirksen指出,为了达到良好的学习效果,你必须给予多种形式的、频繁的反馈。

在EA Sports游戏中,玩家每1-2秒就要做一次决定,每7-10秒得到一次反馈。为了保持流状态,让玩家始终知道自己的行为对结果有影响是非常重要的。流状态是为什么游戏化学习比非游戏化学习更能调动积极性的主要原因之一。

游戏一开始就要建立帮助玩家学习游戏的运作和进展方式的反馈机制。许多电子游戏也是这么做的。为了学习游戏的规则和控制自己的动作,游戏要先让玩有了解简单的情况。当玩家获得足够多的反馈,真正了解游戏的基本原理后,就可以让他们进入游戏的下一关了。

在给予反馈时,另一个要点是,让要反馈具有更明显的“结果性”。也就是,反馈形式本身要与导致它产生的条件或行为有关联。以安全培训为例:在安全问答时,当玩家回答错误时,不是简单地给玩家口头或文本反馈如“回答错误”,而是由设备发出很响亮的“BOOM!!”声。这种反馈形式与目标学习对象和环境具有紧密的联系。

根据Dirksen,这些反馈方法比随意的徽章和无意义的得分更有效得多。

用兴趣维持注意力

当Dirksen问道:“你对某事物的注意力可以维持多长时间?”与会者都很谨慎,没有给出很大的数字。考虑到我们自己的上学经历和培训师在“表现技能”训练中告诉我们的东西,我们知道人类的注意力不可能维持太长时间,所以我们的回答是“大约10分钟吧。”

Dirksen却否定道:“但事实并非如此。有些人可以在电影院里把《指环王》三步曲一次性看到完。”

真相是,如果你给予玩家/学习者/观众他们想要的东西,他们的注意力就会持续。在我看来,以下3个做法是有效的:

1、以开放循环作为开头,刺激他们产生兴趣

2、保证他们确实得到3个最重要的问题的答案

3、保证玩家(容易)学习游戏的结构

奖励应该即时且有意义

Dirksen向我们解释了游戏化学习中的奖励方式。

在许多训练中,参与者并没有意识到“他们这么做是为了什么”,直到训练过程进入尾声。在学习或游戏中,参考者通常直到活动的结尾甚至结束后才得到学习或游戏表现的奖励(反馈或其他奖品)。但心理学和日常生活中的许多例子均表明,人们更加关注立即的奖励,更不是更迟出现的奖励。吸烟者就是一个好例子;他们选择不健康的即刻嗜好而不是长远的健康。这个基本原则的一个例外是,如果奖励非常丰富,我们就会乐意等待(游戏邦注:等待的时间越长,奖励就应该越大)。

所以,除非奖励非常可观,否则游戏中的奖励应该尽早出现。

另外,奖励应该对学习者有意义。随机徽章、积分和奖项并不能长久地提高玩家在游戏中的表现。Dirksen举了个例子:在数学课上,如果能够把问题和例子与学习者的生活联系起来,参与者学习数学的内在奖励就会更大。又例如,对于进修数学的未来创业者,不要使用任意的数学游戏,而要根据成功经营商业的想法来设计数学游戏。

Dirksen展示了一个为呼叫中心的人设计的简单的游戏。这些人需要记住不能泄露敏感信息给竞争者,否则后者可能会假装成他们的客户。为了达到训练目的,他们要玩一个游戏:屏幕上浮动着不同的图标,他们要射中竞争对手的图标。尽管乍一听似乎不错(强化竞争对手是“糟糕”的印象),但Dirksen指出这个游戏在如下层面上说是失败的:

1、在现实中,呼叫员在呼叫时并不会看到竞争对手的图标。这个游戏与他们应该注意(或听)的实际行为没有关系。

2、大多数呼叫员在工作中不需要使用枪。赢得游戏的行为与现实生活的行为没有关系。

3、游戏行为太过激进,可能刺激呼叫员粗暴对待任何他们在工作中遇到的竞争者。

应该按玩家的能力渐增挑战难度

如果我让我的女儿们跟威廉姆斯姐妹对决网球,她们不仅会在巨大的压力下输掉比赛,而且学不到太多东西。为了使游戏化学习更有效,挑战难度应该落在“流地带”中:

根据Dirksen所述,许多传统的训练落在上图的无聊地带中,不是因为训练本身很无聊,而是因为缺少挑战性。使用游戏化方法,我们可以制造挑战,但我们要谨慎一些,避免把难度提高得太快,给学习者太大压力。我们要根据学习者的能力提升来增加游戏化的挑战难度。

听完Dirksen的演讲后,我想到,如果能使用游戏,我自己训练可以大大改进。但即使我不想把学习过程游戏化,但我认为在训练中遵循这些反馈、注意力、奖励、产出和挑战的原则相结合,是非常重要的。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

4 Tips for Game Design and Learning, from Julie Dirksen

by Dan Steer

If, like me, you believe gamification for learning is worth exploring, you might be getting started on your first attempts at game design. When you have your basic idea for a game or how to bring game-mechanics into a learning initiative, what do you need to keep in mind to be successful? What specific game design principles must be followed? Julie Dirksen suggests the following…

Feedback mechanisms have to be used well

Dirksen says that to create good learning you need to give extremely frequent feedback, in diverse ways.

EA sports games are designed so you have to make a decision every 1-2 seconds and you get feedback on this every 7-10 seconds. Knowing where you are and how your behaviour has impact on results is important to keep players in flow. Flow is one major reason why gamified learning is more motivating than non-gamified learning.

As your game starts, build in feedback mechanisms that help players to learn how the game works and how they can progress. This approach is also used a lot in video games. The player is taken through simple situations in order to learn the rules of the environment and how to control her actions. When enough feedback has been given to really understand the basic principles, we can throw in something to take them to the next level of the game.

Another important element in giving feedback is to make it seem more “consequential”. This means that the feedback style itself is linked to the context or impact of the behaviour that leads to it. The example given is of a safety/security training: Instead of giving a simple verbal or text-based feedback that says “wrong answer”, players get a big noisy “BOOM!!” sound with a scary message about having just blown up the facility. In this way, the feedback style is linked to the desired learning and the environment in question.

According to Dirksen, these kinds of feedback approaches are far more effective than random badges and points that go no-where.

People only give their attention if they want to

When Dirksen asks “How long can you pay attention to something?” the participants of session W306 are careful not to give big numbers. Thinking of our own school experience and what trainers tell us in “Presentation Skills” training, we know it can’t be too long and we answer “about 10 minutes”.

“But it’s not true”, says Dirksen, adding that “some people watch all 3 extended “Lord of the Rings” movies back-to-back at the cinema.”

The fact is that if you give players/learners/spectators what they want, they will give you their attention. In my opinion, the following 3 ideas will help:

Start with an open-loop to build intrigue (see notes on Karl Kapp’s session)

..but be sure they finally do get the answer to the 3 most important questions

Be sure the structure of the game becomes known (easily) to the players

People respond best to relevant rewards they get now

Dirksen spoke to us about the way rewards should be used in gamified learning.

In much training, participants don’t really realise “what is in it for them” until quite late in the process. And the rewards that are given for learning or game performance (feedback or other rewards) are not given until quite late, maybe only after the game. But psychology and everyday life show many examples of how people focus more on immediate rewards and less on rewards that comes later. The obvious example is of smokers who choose to have un-healthly pleasure now over health (or lack of bad-health) later. The major exception to this basic rule is that if the reward appears to be very high, we will be willing to wait for it. (And the further away the reward is, the bigger it needs to be.)

So unless you have a really good pay-off, bring in game rewards early on.

Rewards also have to be meaningful to the learner. Random badges, points and prizes do not improve game performance over time. Dirksen gave the example of how the inherent reward of the learning itself in a maths class could be better tailored to fit participants by using problems and examples that are related to their own reality. For example, for future entrepreneurs who need maths training, rather than creating a random maths game, you could create a maths-game around the ideas of successfully running a business.

This last point reinforces another Dirksen tip: Match game deliverables to desired behaviours and business deliverables

Dirksen showed as a simple game created for call-centre learners who needed to remember not to give away sensitive information to competitors who might call them pretending to be clients. In order to achieve this, they were asked to play a game where different logos floated down the screen and they had to shoot the ones of their competitors. Although the first look might suggest this is fine (it reinforces the idea that competitors are “bad”) Dirksen said it failed on several levels:

In reality, call-agents do not see the logos of their competitors when they call. The game did not involve the actual behaviours they should look (or listen!) out for.

Most call-agents do not have guns at work The winning game behaviour did not match the desired real-life behaviour.

The game-behaviour was very aggressive and might encourage call-agents to be aggressive towards any competitors they did encounter in their calls.

Challenges must be incremental and in line with the players current competence

If I place my daughters by the tennis court opposite the Williams sisters, not only will they lose, but they will likely find it very stressful and not learn very much. To be effective with gamified learning, challenges must fall within the “flow-zone”…

According to Dirksen, much traditionally training falls into the boring side of the chart, not because it is inherently boring, but because of the lack of challenge. Using a gamified approach, we

can create challenge, but we must be careful not to go too far too quickly as this can bring stress to the learner. And as competence rises, so must the gamified challenge…

Having listened to Dirksen and Kapp at the ASTD2013 ICE, I had the opinion that many elements of my own training could be dramatically improved by the use of game. But even if I don’t want to gamify things, I think it is important to align training with these principles of feedback, attention, reward, deliverables and challenge.(source:dansteer.wordpress)

上一篇:解析游戏迭代开发的概念及工作流程

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号