分析《Primordia》故事叙述的设计问题及解决方法

作者:Upplagd av Thomas kl

引言

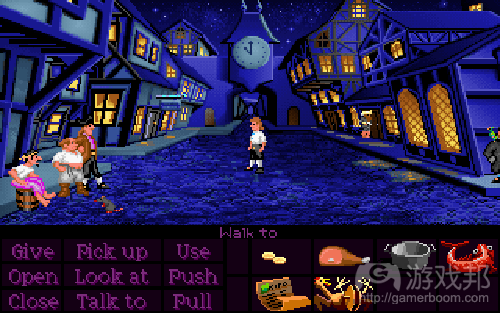

我最近玩了即将面市的冒险游戏《Primordia》的试玩版。我很喜欢它的美术风格、背景、主题和角色(可能除了有些令人讨厌的同伴是例外)。不过,我发现自己玩的时候并没有太投入。主要原因是,它是非常传统的点击游戏,这意味着解决益智题是主要活动。尽管有些设计和线索系统不错,但作为核心的玩法却拖了游戏的后腿。

声明:我没有说《Primordia》是一款糟糕的游戏,更多解释请看结论段。

与此同时,我们的项目《Super Secret Project》的设计思考也已经进展到一半了。我们正在尝试改进我们在之前的游戏中使用的几种设计法,在这个过程中,我们遇到了一些问题,但最终想到一些有趣的见解。

我认为《Primordia》的问题和我们自己的项目问题,都与故事叙述的设计法大有关系。本文的议题也在于。我将首先介绍基本问题,然后解释我们最近的改进措施,最后总结我们的方法。

沉浸感

自大约上世纪90年代中叶,冒险游戏作为游戏叙述之王的地位已经衰落了。它们开始让位于更加动作向的游戏。以至于今天,开发者把制作故事的大部分努力都放在动作冒险游戏中。事实上,这意味着益智题为中心的设计法已经被某些以组成玩家体验的核心机制为中心的设计法取代了。

我认为这些办法都不能很好地处理游戏中的故事叙述。二者的问题都是,它们过分强调游戏的竞争性。二者的目标都不是让玩家产生沉浸感,而是让玩家挑战成功。我在之前的文章中详细地讨论过这个问题。重点如下:

1、挑战导向型游戏有一个我称之为“黑盒设计”的核心设计。这意味着玩家的主要目标是凭直觉想出游戏的潜层系统并击败它。

2、当开发者的关注焦点是游戏的系统时,他们就无法重视游戏的故事。结果是,游戏的故事方面非常薄弱。

3、故事导向型游戏的主要目标是创造沉浸感,或更准确地说是存在感。达到该目的的方法是,在玩家和游戏之间形成牢固的、持续的输入-输出循环。

在深入以创造沉浸感为目标的设计法以前,我们必须讨论一下冒险游戏的一般设计方法。

益智题设计法

这是经典冒险游戏的基本设计法。这类游戏基本上由一系列互相联系的任务组成。也就是说,玩家要完成A,必须先完成B和C,而完成C要求解决D和E等等。整个游戏简直就是一个玩家必须解决的大益智题。

这个方法的历史可以追溯到第一款冒险游戏《Adventure》。这款游戏一开始只有一个洞穴系统。当游戏作者William Crowther制作它的互动版本时,部分是因为受《龙与地下城》的启发,他添加了各种益智元素。显然,作者认为单纯地探索虚拟洞穴不能产生足够的沉浸感。必须再添加一些东西,所以益智元素就填补了这些空缺;这个设计决定影响了后来的好几代冒险游戏(我很好奇如果Crowther添加的是一些“Dear Esther”式的故事元素,冒险游戏的历史是否会被改写)。

这个方法这么成功的原因是,很容易将交互环境与故事相融合。益智题为玩家提供了各种任务,成为玩家继续游戏的动机。更重要的是,让玩家成为游戏世界的一部分——使玩家与角色的对话变得有意义了,并且迫使玩家理解虚拟世界的运作方式。

但这个方法也有缺陷。因为益智题的目的是不断地给玩家提供谜题和任务,所以游戏必须有支持这一目的的故事。要有玩家与角色对话的原因、要有发放明确的任务的方式、要有安排支持益智题的障碍和环境。结果显而易见:大多数冒险游戏不是成为神秘/侦探故事的变种,就是成为名著、传说、史诗故事的翻版。

这首先产生了本文所说的问题,也就是,不断地检查游戏世界会破坏游戏的真实感。这样,玩家就不可能沉浸于游戏的故事了。如果他们不能保持解决益智题的心态,他们就无法在游戏世界中前进。这通常导致一种怪异的处境:看着攻略玩游戏比自己摸索游戏更有趣。

我们很早就意识到这些问题了,但直到最近,有些开发者才开始尝试用不同的方法解决它们。以下我将分别探讨的是最常用的和最成功的解决方案。

线性情节设计法

这个方法的基本前提是,开发者制作一款像一般的非文字冒险小说的游戏;然后检查原本是被动体验的部分是否可以插入玩家互动活动(游戏邦注:游戏制作的真实情况当然比这个复杂,但基本上概括了这一类型的设计过程)。我知道的采用这种方法的第一款游戏是《Photopia》,它做得非常到位。人们普遍认为这款游戏的体验很能唤起玩家的共鸣。之后,推广这一方法的游戏是《Fahrenheit》;不幸地是,玩家对它的评价并不高。再后来,Telltale将漫画《行尸走肉》成功地改编为游戏,大大证明了这个方法的实用性,显示了它吸引受众的优势所在。我认为《行尸走肉》是目前为止使用线性情节设计法最为成功的游戏。另外,《To The Moon》也是通过该方法达到良好效果的另一个典范。

这个方法之所以这么有效,是因为线性情节更容易保持故事的发展势头。当使用益智题设计法时,玩家非常可能遇上过不去的坎,从而破坏游戏体验。而这种情况在使用线性情节的游戏中极少发生,因为游戏太专注于故事了。在玩家能控制情节走向以前,在不破坏沉浸感的情况下,主角可以非常明确地告诉玩家下一步要做什么。

我认为这个方法表现最突出的优点是,为玩家提供了沉浸于游戏的强大场面。《Heavy》有地下室俘虏和自残场面。《行尸走肉》有楼梯防御战和安乐死的场面。通过严格的和受控的游戏路径,游戏可以把玩家置于非常特定的场景,而这在其他游戏中是很难达到的。

另一个显著的优点是,使游戏具有更加多变的故事,因为不必把所有元素都放进益智题的结构中。这个方法强调游戏本身的品质,而不是竞争性(黑盒)。像《Photopia》和《行尸走肉》这样的游戏充分证明了这个方法的有效性,也许还有进一步探索的空间。

当然,按这种方法设计游戏也不是没有缺点。有些方面甚至大有问题。主要问题是,游戏中其实没有太多交互活动,特别是创造存在感方面。其实,这个方法的基本前提本身就是一个缺点,所以没什么可讨论的。然而,更微秒更有趣的问题是出现在选择发生交互活动的部分的时候。主要有两个问题:

第一个问题是,交互活动难以保持一致性,部分是因为活动变化太多,部分是因为太少发生。《暴雨》采用了快速反应事件(QTE),效果不是太好。虽然有些场景确实不错,但总体看来,任意按键输入太多了。《行尸走肉》做得就好多了,因为它的输入类型更直观,更少,如瞄准十字准星。但少见的用法和不总是明确的功能使这个问题持续存在。对话通常比较管用,但那种交互活动缺少紧密的反馈循环(然而,如果能通过设置时限和恰到好处地安排各个选项的后果,这两款游戏的沉浸感就会更强了)。

另一个问题是,探索感大大消失了。玩家的探索空间总是有限的和静态的。原因是,游戏始终必须保证玩家在互动环节结束后返回“过场动画模式”。因为要达到非常特定的要求,游戏就遇上瓶颈了。这意味着,为了使下一个场景与上一个场景保持连贯性,游戏必须非常小心地移动角色,改变环境等。还有一个问题是,当开始缺少过场动画那种精心修饰的画面的、控制较少的环节时,如何保持角色的质量。这意味着,在这些更加开放的事件中,玩家能对角色做的事太少了。最后,因为游戏必须保持操作方案的整体统一性,任何开放环节只能有最简单的输入。通常只允许玩家移动,其他活动则要通过某些菜单来执行(基本上就像点击类游戏)。在这些部分,交互活动显得非常迟钝和不自然。

这对生产也有大问题。在简单的游戏如《Photopia》和《To The Moon》中,这个问题倒是不严重,但在像《暴雨》这样复杂的游戏中,影响就明显了。因为玩家在游戏中很多时候并不是主动地玩,而是被动地看,所以过场动画的品质必须非常高。游戏必须保证在反馈循环很弱或完全缺失的情况下,还能保持玩家的沉浸感。这意味着工作量会很大,进而导致游戏必须提前计划。例如,《暴雨》在进入制作环节以前,就已经做出完整的脚本了。在制作玩法以前,就要完成所有动作捕捉和录音工作。当进入正式制作阶段时,就很难再修改和推倒重来了,基本上要严格按照脚本来制作。对于互动媒体,这是一个很大的劣势,因为约束过死反而很难产生真正的好作品。

虽然线性情节设计有助于产生更流畅的故事和更连贯的沉浸感体验,它仍然有缺点。主要问题是,互动玩法过少和探索感严重缺失。这是必须解决的问题。对于我们即将问市的项目《Super Secret Project》,我们打算尝试不同的设计思路,使之成为一种玩家全程参与的体验。

场景设计法

我将我们想出来的这种设计法命名为“场景设计法”。它的基本思路就是,设计师给玩家提供可以自由活动的场地、场景;玩家满足一定要求后可以离开和进入下一个场景。各个场景都必须围绕某种形式的活动和/或主题展开。移动到下一个场景应该有明显表示,无论是通过非常简单的交互活动(如打开门)还是更复杂一些的活动形式(如启动某种发生器)或进入某种状态(如等待2分钟)。游戏必须从头到尾遵循相同的深层机制,且必须保证交互活动的连贯性。理想的结果是,游戏不仅故事叙述全程流畅,而且保持紧密的互动循环和深刻的沉浸感。这基本上是从线性情节设计法中取出较好的交互片段,用场景拓展它们,以强化整体的连贯性。

这可能吗?在线性情节设计法中,交互片段始终是小心设置的,一般情况下是非常集中和受限的。所以,在更加开放的环境中重制交互时刻且不加入任何过场动画,真的可能吗?场景设计法不可能重制线性情节游戏中的所有场合,但如果处理妥当,应该可以达到相当接近的效果。

第一个要求是,奖励玩家,促使玩家按某种方式行动——应该以此为目的设计关卡。例如,在初期设计中,我们尝试给予玩家大量行动自由,但这些自由的结果大多导致玩家的行为与故事叙述相背离。这是消极的自由。所以我们只能尝试根据“主人公这么做才合理”的原则来限制玩家行动,以便不破坏故事的一致性。这是积极的自由。我们的目标是消灭消极自由,最大化积极自由——但是,说的容易做的难。

甚至对于设计得很巧妙的场景,也会有不完满的地方——仍然有传达目标的问题。更早以前,我以为这只是一个场景必须足够有趣、玩家必须参与游戏提供的活动的问题。而真正的问题是,场景越大,玩家越难想出它的有趣和无聊之处;玩家很容易失去方向感,变得不知所措。现在,这个问题甚至更加严重了,以至于我们不得不再次将它作为关注焦点。玩家不是时时保持不断寻找线索的状态,而是更关注了解故事发展和身临斯其境的体验。

这就是我们希望的结果,这样玩家的进程就不会被阻碍了。

为了解决上述问题,我们必须保证:场景越大,目标越清楚和明显。另外,大区域中的任何活动都应该总是选择性的,除非其在空间上和概念上都与游戏进程的目标或状态紧密相关。无论何时游戏要求玩家执行活动时,场景的视野都应该缩小。活动的自由度越大,活动的强制性就应该越低。

尽管场景本身不是唯一的问题。也许更大的问题是如何联系它们。一开始,我认为难度不大,联系不紧也无所谓。然而,很快就遇上麻烦了,主要是出在玩家体验上。各个场景之间必须具有某种逻辑上和情节上的联系。如果没有,玩家就会很迷惑自己该做什么。这意味着要么降低积极自由的程度,要么给各个场景添加更多点缀。第一种做法类似于《Thirty Flights of Loving》,第二种做法基本上相当于使用线性情节设计法。这两种方案我们都不想要,所以清楚的联系是必须的。

这就产生了一个有点儿古怪的结论。我们对故事叙述树立的目标之一是,尽量少依靠情节,以便增强体验的沉浸感。然而,为了产生尽可能多的积极自由,场景必须以非常紧密的方式安排在一起。换句话说,在实际场景中,为了少使用情节,那么情节本身就要更加强大。进而,这就限制了可用的场景类型。既然联系必须合情合理,那么就不可能单纯地用对核心机制作用不大的场景填充游戏。到现在,我们已经能够很好地处理这个问题了,但我们仍然在研究这些概念。

结论

本文的结论不是对如何改进冒险游戏的最终判决,只是对我们在下一款游戏中采取的设计方向作一番总结。一切都还没完成,所以我不肯定最终结果会怎么样,或者以上设计法我们会使用到什么程度。至少我们现在已经有思路了。

我在上文中提到传统的点击游戏,听起似乎我很反感这类游戏,但事实上不是这样的。我喜欢许多冒险游戏,使用益智题是一个非常有效的设计法。优秀的冒险游戏确实会充分利用益智题,例如,《猴岛》和《断剑之魂》。

这些游戏的设计方法很有效,确实产生了非常令人难忘的独特体验。然而,对于有些游戏,如《Primordia》,我的游戏主要目标不是这种体验。这那款游戏中,我更感兴趣的是探索和沉浸于游戏世界。经典的益智游戏设计没有恰当地处理这一点,所以我觉得我的体验并没有达到应有的效果。《Primordia》仍然是一款好游戏,它的场景安排很好,使某些益智题变得非常有趣。但我的感觉是,它本可以把大量精华放进游戏,并以更好的方式表现它们。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

High-Level Storytelling Design

by Upplagd av Thomas kl

Introduction

I recently started to play the demo for the upcoming adventure game Primordia. I really like the art-style, the setting, themes and the characters (perhaps with the exception of a somewhat annoying companion). Despite this I am finding myself not being that engaged when playing it. The main reason for this is that the game is in a very traditional point-and-click form, which means that it is mainly all about solving puzzles. Despite some good design and an in-game hint system, its gameplay back-bone is holding it back.

Note: This does not mean that Primordia is bad game though, more on this in the end notes.

At the same time we have currently been in the middle of going over some design thinking in our upcoming Super Secret Project. We have been trying to evolve the type of high level design we have used for our previous games and in that process encountered a few problems and come to a few intriguing insights.

The problems I had with Primordia and the issues we have had with our own project are closely related and deal with the high level design used for games focusing on story-telling. This sort of

design is what this post will be about. I will start by going over the basic problems, then cover more recent advancements and finally outline our own approach.

The Immersion Conjecture

Since the middle of the 90s or so, the image of adventure games as the kings of videogame storytelling has slowly dwindled. Instead they have given way to more action oriented titles and nowadays most of the major storytelling efforts lie in the action-adventure genre. What has happened is that the puzzle-centric design has been replaced by one where some sort of core mechanic makes up the bulk of the experience.

I think neither of these approaches is a good way to properly do storytelling in a game. The problem with both are that they have a strong focus on the competitive aspect of games. In both of these designs the main goal is not about being immersed but about beating challenges. I have discussed this to great lengths in the paper The Self, Presence and Storytelling. The points important for this discussion are the following:

Challenge-oriented games have a core design which I call “black box design”. This means that the main goal for the player is to intuitively figure out the game’s underlying systems and to beat

them.

When the focus is on a system of a game, it detracts attention from, or even directly contradicts, its fiction. As a result it diminishes the story aspects of the game.

The main focus of games with storytelling should instead be on creating immersion or, more precisely put, a sense of presence. This is done by having a strong continuous input-out loop between the player and game.

Before going into high level approaches that focus on immersion, the normal adventure design need to be discussed.

The Puzzle Approach

This approach is pretty much how all of the classic adventure games are built. In essence, they are made up from a set of interconnected tasks that need to be completed. In order to get to A you need to B and C, C requires that D and E are done and so forth. The entire game basically becomes a big puzzle for the player to solve.

This approach has its root in the very first adventure games ever made: Adventure. The game started out as a mapping of a cave system that the author, William Crowther, had been part of exploring.

When making an interactive version of it, various puzzle elements, partly inspired by D & D, were added. Apparently the author did not find the virtual exploration of the caves engaging enough on its own. Something more was needed, and the puzzle elements was added to fill that void; a decision that would go on to influence the coming decades of adventure games. (I wonder how different history would be if Crowther had added some Dear Esther-like narrative instead!).

The reason why this approach is so successful is because it makes it very easy to weave an interactive environment together with a story. The puzzles always give the player various tasks to do

which provides motivation to go forward. More importantly it serves as a mean for the player to become part of the game’s world. It makes it meaningful to converse with characters and it forces players to understand how the virtual world works.

This comes as a cost though. Because the focus is on constantly providing riddles and quests for the player, the game must have a story that support this. There must be a reason for the player to question characters, ways to provide clear goals, plenty opportunity to set up obstacles and an environment that support clever puzzles. The result of this can be seen very clearly; most adventure game are either some variation on mystery/detective story or a classic, fairytale-like, grand quest one.

On top of this comes the problem discussed in the paper, namely that the constant scrutinizing of the game’s world eats away on the player’s make-belief. It is simply not possible for players to

let story-engagement be their main focus. If they fail to stay in a puzzle solving mindset the game will refuse them to advance. This often leads to the somewhat weird situation where playing the game with a guide is more enjoyable than playing it the proper unguided way.

These problem have been known for quite a while, and in recent times some games have popped up that try to do things differently. I will now discuss the most widely used, and most successful, alternative.

The Linear Plot Approach

The basic premise for this approach is to craft the game like a normal non-interactive story. One then looks for parts were it is possible to insert some sort of player interaction and add these to the otherwise passive experience. (This is not how would go about creation such a game exactly, but it describes the type design quite nicely.) The first game I know that did this was Photopia, and it used it very successfully. It is widely regarded as a highly rewarding and emotional experience. The approach has been more popularized by Fahrenheit, which unfortunately got a much more negative response. More recently the approach gained a lot of success in Telltale’s adaption of The Walking Dead and here this approach have really showed its advantage to a bigger audience. I think it is by far the best usage of a linear plot design done so far. To The Moon is another, and different, example that also uses this approach to great effect.

What makes this approach so effective is that it is much better at keeping up the narrative momentum. When using the puzzle approach, it is highly likely that players will get stuck and taken out of the experience. With the linear plot approach this happen very rarely since the game is so focused. Right before it is time to give the player control, the protagonist can pretty much explicitly state what is needed to be done without it feeling out of place.

What I find striking about this approach is the very strong scenes that the games let you take part in. Heavy has the basement capture and self-mutilation scene. Walking Dead has the staircase

stand off and mercy killing scenes. By having a very strict and controlled path throughout the game, it is possible put the player inside very specific scenes that would have been hard to set up in other kind of games.

Another big advantage is that it allows for a lot more diverse stories, as there is much less pressure on building everything into a puzzle structure. The approach has focus on the presence

building qualities of the game medium instead of the competitive (black-box) aspects. Games like Photopia and Walking Dead clearly show how effective this is and there is probably a lot more that can be explored here.

Of course all is not well with designing a game in this way. There are some areas that are really problematic. The main issue is that there is not really much interaction, especially when it comes

to building a sense of presence. The basic premise of the approach is just this, so it is really an intrinsic fault and not that interesting to discuss. However, more subtle, and intriguing,

problems arise when it comes to picking the actual parts where the interaction happen. Two main issues arise here.

One is that it is very hard to have some sort of consistency in interaction, partly because activities can be so diverse and partly because they happen so rarely. Heavy Rain went the route of QTE’s and the result is not that good. While there are some really good scenes, as a whole there are just too many arbitrary button presses. Walking Dead does it a lot better with having a few types of more intuitive input, such as aiming a cross-hair and mashing a single button. But the infrequent usage and not always clear functioning makes this problematic still. Dialog usually work better, but that interaction lacks a tight feedback loop instead. (However, an interesting way in which both games try and make this more immersive if by having a time-limit and banging on about how every choice has consequences).

The other issue is that much of the sense of exploration evaporates. Whenever players are given a space to explore it is very confined and static. The cause of this is that the game always need to make sure that you can go back into “cut scene mode” after an interactive section is over. There is a bottleneck that needs to be reached with very specific requirements met. This means one has to be very careful about moving characters, changing the environment, and so on, in order for the next cut scene to feel coherent. There is also the problem of keeping the quality of characters when starting a less controlled section that lack the tightly polished look of a cut scene. This means only so much can be done with characters during these more open sequences. Finally, because you need to have some overall unity in the control scheme, any open sections can only have the simplest of input. Usually only movement is allowed and the rest handled by some sort of menu like system (basically like a point-and-click game). In the end interaction during these part come off as clunky and contrived.

There is also a big problem when it comes to production. Simpler games like Photopia and To The Moon do not suffer so much from this, but in a game like Heavy Rain it is very evident. Because much of the game is not actively played but passively watched , the need for high quality cut scenes is a must. It needs to be made sure that the player can be engaged when the presence-feedback loop is weak or completely missing. This means tons of assets, which in turn requires the game to be planned far ahead. For instance, Heavy Rain had the complete script written before the production started. And then all motion capture and voice recording needed to be done before gameplay could be tried out. When it comes to making the actual game there is little room for change and iteration, and one basically has to stick with the script. This is a big disadvantage for interactive media as much of the real good stuff can come from unexpected directions.

While linear plot design gives a better sense of flow in the narrative and a more coherently immersive experience, it still feels lacking. The main problem is that there is so much interactive down-time and great loss in the feeling of exploration. There needs to be some other way of doing things. For our upcoming Super Secret Project we wanted to try a different route and craft an

experience where you play the whole time.

The Scene Approach

The design that we have come up with is something I will refer to as the “Scene Approach”. The basic idea is that you give the player an area, a scene, where they are free to roam. When appropriate players are able to leave and enter the next scene. Each scene should have a strong focus on some form of activity and/or theme and be self contained. Moving on to the next scene should be evident, either by a very simple interaction (e.g. opening a door), some form of activity (e.g. starting a generator) or by reaching some sort of state (e.g. waiting for a 2 minutes). The same underlying base mechanics should be used throughout the game and interactions should behave in a consistent manner. The wanted end result is to have an experience where the narrative flows throughout the game, but retains a tight interaction loop and a strong sense of agency. It is basically about taking the better interactive moments from the linear plot approach and stretching them out into scenes with globally coherent interaction.

Is this really possible? The moments in the linear plot approach have been carefully set up and are normally extremely focused and contained. Is it really possible to recreate this in a more open environment and without any cut scenes? The scene approach cannot possibility recreate every situation found in a linear plot game, but if done correctly it should be possible to come pretty close.

The first requirement is that the levels need to be designed in such a way that players are rewarded and driven towards behaving in certain ways. For instance, in early designs we tried to give

tons of freedom in what players could do, but much of this freedom resulted in actions that went against the narrative. This is negative freedom. Instead we have tried to limit actions into “what makes sense for the protagonist to do” and do so without breaking any sort of consistency. This is positive freedom. The goal is then to eliminate the negative freedom and maximize the positive one, which is very simple to say but have proven hard to do in practice.

Even with a neatly designed scene, all is not set. There is still the problem of communicating the goals. Early on I thought that it was just a matter of having an interesting enough environment

and players would partake in the activities provided. The problem is that the larger the environments become the harder it is for players to figure out what is of interest and what is not. It is

also very easy to loose ones sense of direction and become unsure of what to do next. This problem is even more severe now that we pulled back on the problem solving focus. Players are not in the mood for constantly looking for clues but are instead focused on soaking up the narrative and having an immersive experience. This is how we want them to be, and should thus not be something that hinders progress.

To get around this, we have had to made sure that the larger a scene is, the more clear and obvious your end goal becomes. Also, any activity in a large area should always be optional unless it is closely related, both spatially and conceptually, to the object or state that makes the game progress to the next scene. Whenever the player is required to carry out some activity, the scope of a scene need to be decreased. The greater the freedom is in terms of possible actions, the less actions must be compulsory.

The scenes themselves are not the only problem though. A perhaps even greater concern is how to connect them. At first I thought this would not be a big issue and that you could get away with pretty loose connections. Problems arise very quickly though, the main being that the experience simply stops making sense for the player. There must be some sort of logical connection and narrative flow between each scene. If not it becomes increasingly harder for player to figure out what they should be doing. This means either lowering the degrees of positive freedom or to have more set up for each scene. The first option gives something like Thirty Flights of Loving and the second is basically to use the linear plot approach. We do not want to do either, so having clear connections is a must.

This results in an a sort of curious conclusion. One of our goals in storytelling is to rely as little as possible on plot in order to give an experience with a strong sense of agency. However, in

order to provide as much positive freedom as possible, it is essential that the scenes are put together in a very tight and engaging fashion. In other words, on a scene level there is a great need

for a strong plot in order to have as little plot as possible in the actual scenes.

In turn this limits what kind of scenes that are possible. Now that the connections need to make sense, it is not possible to simply fill the game with scenes that lends themselves very well to our core mechanics. So far we have to been able to pull this off quite nicely, and we are slowly wrapping our minds around these concepts.

End Notes

This is not some final verdict on how to improve upon the adventure game genre. It just summarizes a bit on the design direction that we are taking for our next game. Nothing is final yet, so I am not sure how it all will turn out in the end, or how much of the above we will be actually using. This is at least our current thinking and what we are working on now.

Also have say few ending words on adventure games in general. It might sound in the beginning like I loathe traditional click and point games, but this is not the case. I have enjoyed playing a lot of adventure games, and using puzzle approach for high-level game design is a very valid one. The best adventure games really take advantage of this, for instance Monkey Island and Broken Sword.

These games are made in a way that makes the design really works and creates a really memorable and unique experience. However, for some games, like Primordia, my main draw is not to have this kind of experience. In this game I am more interested in exploration and getting immersed in the world. The classic puzzle design does not do this properly and I feel as if my experience is not as good as it can be. Primordia is still a good game and it uses the setting nicely to create some interesting puzzles. But it feels like they could have taken a lot of the game’s essence and packaged into a form that would have delivered it much better.(source:frictionalgames)

上一篇:阐述玩家社区对于游戏成功的重要性

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号