游戏教程是否会扼杀玩家的创造力?

作者:Jame Madigan

先思考一下这个问题:我们应该通过游戏教程手把手地教会新玩家游戏的所有机制和难点,还是放手让玩家自己摸索?

在电子游戏中,“教学关卡”如此普遍,以至于当某游戏不能提供详细到保证玩家学会Y键有何作用的教学关卡时,该游戏就会显得相当另类。例如,本周初,我开始玩游戏《Faster Than Light》,虽然这款游戏确实提供了一分简单的教程和许多工具提示条,但要学会如何玩游戏,很大程度上还是要靠玩家自己的努力。玩这款游戏的前半个小时,我不停地咒骂和抱怨“为什么我要花钱升级门?”、“等等,为什么这些房间都变成粉色的了?”、“天呐!为什么开火了?开什么火?怎么开火?……游戏怎么结束了?”

(《Faster Than Light》先简单地向玩家介绍游戏,然后就把玩家丢进太空中,让玩家自己摸索。)

尽管,我最终上手游戏,并且意识到像《FTL》这种游戏,部分乐趣正是来自用新东西做实验、自己学习如何最大化生存希望。这并非不同于系统导向的沙盒游戏如《我的世界》或《泰拉瑞亚》:它们只是把你丢进系统里,告诉你游戏的一半乐趣来自自己摸索(游戏邦注:另一半乐趣来自感觉到自己比其他抱怨游戏没有手把手教学的玩家来得优越。)

这使我想起我从Jonah Lehrer的新书《Imagine: How Creativity Works》中看到的一个心理学实验。在2011年的论文《The Double-Edged Sword of Pedagogy: Instruction Limits Spontaneous Exploration and Discovery》中,Elizabeth Bonawitz及其同事发现不同的指导方式会影响人们探索新系统的方式。这里的“人们”我指的是“小孩子”。这里的“系统”我指的是“玩具”。

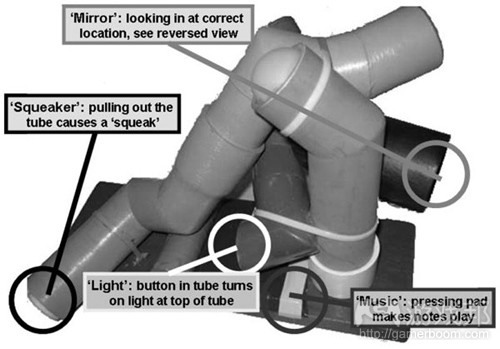

在实验中,研究人员邀请孩子们参观科技馆里的新玩具,不是像你们在黄金时间播放的新闻里报道的那种玩具。这个玩具是一个由具有不同功能的管状物组成的装置,可以发出尖锐的声音,可以发光,还可以播放音乐等。这些功能都很隐蔽,要实验一番才能发现。在一些孩子面前,研究人员摆出玩具,说“哇,看看我的新玩具!”然后她猛拉一条管子,展示玩具如何发出声音,再说“看到了吧?我的玩具就是这么玩的!”

在另一些孩子面前,研究人员摆出玩具,装作她也是第一次见到它的样子,不小心使它发出声音。(孩子们真的很好骗)然后她故作吃惊地说“哇?你们看到了吗?我再试试!”然后她再次猛拉管子。最后她把玩具给孩子们,并告诉他们:“哇,很酷吧?你们自己看看怎么玩这个玩具吧。”

所以,这个实验的关键是,这个玩具的功能很多,但研究人员只向孩子们展示了其中一个(发出尖锐的声音)。对于前一批孩子,这个功能是明确地展示在他们面前的;而对于后一批孩子,这个功能是无意中发现的。

研究人员发现,第一批孩子(研究人员在他们面前展示如何让这个玩具发声)摆弄这个玩具的时间更短,没有什么特别的动作,发现的其他功能也更少。

阅读本文的你们当然不会是小孩子,所以我想你们应该能看出这对电子游戏开发有明确的启示。当别人给我们一样东西,并告诉我们应该怎么操作时,往往限制了我们对其功能的想象。我们的探索行为就更没有创意。我们的大脑往往按阻力最小的方向思考,而手把手的指导恰恰给我们指出了一条最简单的思路。

对于以教会玩家掌握几种技能为目标的游戏,这么做是很好的。但对于以多种系统、选项、策略或方法的交互作用为中心的游戏来说,详尽的指导可能损害玩家和他们对游戏的长期体验。第一次打开《我的世界》这类游戏,思考着”如果我这么做,会怎么样?”是一次有趣的体验,游戏的重点就是促使玩家按这种思路玩游戏。就像被告之“这是会叫的玩具,这么做就能让它叫”的孩子,按照详尽的教程来玩游戏的玩家往往只会想到他们在教程上看到的东西。游戏中的意外、巧合、偶然应该是促进玩家创意和探索的必要元素。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

How Game Tutorials Can Strangle Player Creativity

by Jame Madigan

Okay, let’s do one more article on creativity and games, based on this question: Is it better to hand hold new players through a game tutorial to teach them all the mechanics and intricacies of a game, or is it better to let them figure things out on their own?

The “tutorial level” has become so ubiquitous in video game design that it seems really odd when a game does not go to to painful lengths to make sure you get a slow, measured introduction to every single game mechanic, presumably so you don’t burst into tears over confusion about what the Y button does. For example, I started playing the game FTL (http://www.ftlgame.com/) earlier this week and while the game does offer a brief totorial and many tooltips, it expects a fair amount from you in terms of learning how to play the game on your own. My first half hour with the game consisted mainly of a steady stream of expletives and mutterings like “Why would I ever spend money on door upgrades?” and “Wait, why are all these rooms turning pink?” and “OH GOD! WHY IS THAT ON FIRE? WHAT FIRE? HOW FIRE? …WHAT DO YOU MEAN GAME OVER?”

FTL (or “Faster Than Light” for the cool kids) gives you a brief overview, then tosses you to the space mantis/slug/rock men and expects you to figure the rest out yourself.

Eventually, though, I got into the groove and realized that for a game like FTL, part of the experience should be experimenting with new things, paying attention, and learning how to maximize your chances of survival on your own. It’s not dissimilar to systems driven, sandbox games like Minecraft or Terraria in that way: they just dump you into a system and tell you that figuring it out is half the fun. (The other half is feeling superior to people who complain about it not being spoon fed to them.)

This all reminded me about another psychology experiment I learned about from Jonah Lehrer’s recent book, Imagine: How Creativity Works. In a 2011 paper impressively entitled “The Double-Edged Sword of Pedagogy: Instruction Limits Spontaneous Exploration and Discovery” Elizabeth Bonawitz and her colleagues set out to examine how different modes of instruction affect how creative people get in their exploration of a new system. And by “people” I mean “toddlers.” Yes, toddlers are people; I looked it up. And also by “system” I mean “toy.” Work with me here.

The researchers invited kids visiting a science museum to check out a new toy, except not in that creepy way that you hear about on prime time news shows. The toy was a crazy homemade contraption consisting of tubes that did different things like squeaking, lighting up, and playing music. It’s important that these functions were not obvious and required some experimentation to discover. For some children, the experimenter took out the toy and said something like “Woah, look my badass new toy! Check it out!” Then she yanked on a tube to demonstrate how to make it squeak and finished up with “See that? This is how my toy works!”

For other children, the experimenter took out the toy, acted like she was seeing it for the first time, then pretended to accidentally make it squeak. She then feigned surprise (children are very gullible, it turns out) and said something like “OMGWTF? Did you see that? Let me try to do that!” then made it squeak again. For kids in all conditions, the experimenter gave the toy to the kid and finished by saying “Wow, isn’t that cool? I’m going to let you play and see if you can figure out how the toy works.”

Picture of the toy, taken from Bonawitz et al. (2011).

So, the key points here are that the toy did multiple things, but only one thing (the squeaking) was revealed. For some kids it was explicitly demonstrated and for others it was serendipitously discovered.

What the researchers found was that relative to those in other conditions, children who were given instructions on how to make the toy squeak played with it for shorter amounts of time, did fewer unique actions with it, and discovered fewer of the toy’s other functions.

Now, I understand that most of you reading this are not toddlers, but I think this has clear implications for video games. Because when we are given a thing and told “here is how it works” that presentation tends to constrain the list of things that we consider doing with it. We explore less and are less creative. Our brains tend to take the paths of least resistance, and heavy handed demonstrations create a nice easy rut for our thoughts to follow.

It’s Minecraft. Figure out what you want to do.

Sometimes this is great, as with simple games designed around mastery of a few skills. But for games dependent on the interaction of multiple systems, options, strategies, or approaches, detailed tutorials may hurt the player and their long-term experience with the game. Booting up a game like Minecraft for the first time, blinking a few times, and then saying “Okay, what happens if I do …this?” is a great experience and facilitating that approach is central to the appeal of the game. Like the kids who were told “this is a squeaky toy, here’s how to make it squeak,” players who get their hands held through an hour of tutorials are being mentally primed to consider only what they’re shown. Accident, serendipity, and an occasional bit of rudderless flailing about are sometimes necessary for creativity and exploration.(source:psychologyofgames)

上一篇:解析游戏中计算机制与资源平衡问题

下一篇:科学是游戏开发的妄想还是优势?

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号