行业不应否定电子游戏的叙事方式和潜力

作者:Patrick Holleman

我觉得有必要撰文回应两篇关于电子游戏的故事的文章。但更重要的是评论家Simon Ferrari和作家Tom Bissell之间交换的两封信。虽然他们的信涉及许多与游戏有关的话题,但最让我印象深刻的是Ferrari表示自己无法回头再玩他小时候最喜欢的两款游戏,因为现在从成年人的视角看待那两款游戏中的低劣剧情,只会毁掉他美好的记忆。

Ferrari提到的最喜欢的两款游戏之一是任天堂的经典之作《Chrono Trigger》。无论你怎么想,这款游戏的地位当然不能与《哈姆雷特》或《安娜卡列尼娜》相提并论。然而,作为成年人的我回顾过去的十五年,不得不由衷地欣赏《Chrono Trigger》的设计师们对玩家期待的操纵,无论是玩家对剧情的期待还是对作为一系列关卡的游戏的期待。他们不依靠粗俗的剧情转折,创造了所有电子游戏中最令人印象深刻的故事中的惊喜。更重要的是,他们的创造方法只有在电子游戏中才能完成。

但是,我不想在正文的开头就剧透我后面要说的内容,所以我们先从让Ferrari产生如此感慨的关键原因出发。

先有游戏,然后再有游戏

Will Wright最近表示,游戏不是适用于讲述故事的媒体。公道地说,这个言论可能是受到他的媒体同行的影响,将其作为一种在主要渠道如CNN上宣布他的新电视节目的方法。尽管,我肯定在他的发表的言论中他是作假设。Wright换了另一种说法:电子游戏是叙述故事的可能性吗?我不知道有什么东西可以当作可能性,除非你说的是保险。可能这只是他为了让自己的话听起来不那么尖锐而做的让步。

如果我听到他说游戏不应该讲述故事,我的第一个反应是“否则呢?”游戏讲述故事会怎么样呢?当然,这个问题是没有意义的,因为游戏已经在讲故事了。许多游戏甚至在备受批评的过场动画中讲故事。然而许多这些游戏确实在市场上很受欢迎,这似乎使过场动画的存在变得合理了。Wright的意思是游戏消费者不知道在哪买不讲故事的“真正”游戏吗?或者消费者的品味很差?这些问题也没有什么意义,因为我刚才说了,讲述故事的游戏已经存在了,并且非常受欢迎。我不能想象,Wright会阻止得了人们制作讲故事的游戏,并以此谋生。

我认为有一个潜在的问题刺激着Wright和其他业内人士认为游戏不应该讲故事,或不应该以游戏现在的方式讲故事。这个问题是,Wright把电子游戏当作传统游戏的扩展版,而传统游戏是没有故事的。(我说的传统游戏是指国际象棋、扑克牌、《大富翁》等)我同意西洋陆军棋如果包含故事,将会非常糟糕。虽然有些“桌面”游戏是有故事的,如《龙与地下城》,但桌面角色扮演游戏是另一回事。对吧?

正如我在文章开头提到的,另一位游戏圈知名人士,评论家Simon Ferrari最近对此发表了评论。他表示:

我认为,模拟游戏和数字游戏的设计之间,几乎不存在形式上的差异,但是,我们应该认识到它们存在财政差异、文化差异、品味差异和设备差异——比如,复杂的游戏状态的存储和检索、动态和即时玩法、材料等要依靠电脑的大容量和多功能才有可能实现,而不是通过传统的规则执行。

Ferrari的意思似乎是,尽管游戏的设备已经改变了,但游戏的基本属性并没有改变;它们只是看起来有点不一样。

我认为这可能是游戏讲述故事的支持者和反对者发生分歧的地方。

Ferrari将古代中国和希腊的游戏以及它们的“玩耍、运动和游戏的评论和庆典”与现在的游戏联系起来。我认为正是在这个地方,他意外地突出了一个重要的差别。运动也是游戏。当Mohammed Ali在1974年的拳击比赛时奚落George Foreman——用右手指,通过话筒中冲他大声叫,他当时采取的是一种经典的游戏策略:故意惹怒对手。在国际象棋或扑克牌中也可以实施相同的策略并且同样能成功。然而,如果你考虑到最优秀的运动作品,它强调的东西与最优秀的游戏故事是不一样的。 我想不出有哪个游戏专家会建议我们消除运动的肉体性或不让裁判人员使用录影机即时重放功能,因为它们与传统游戏是不一样的。

与此类似,运动和传统的/桌面游戏和电子游戏也各不相同。所以当Ferrari声称他认为电子游戏和传统游戏之间没有形式上的差别时,我敢说他没有考虑到AI和独立模拟的游戏世界。在传统游戏中,游戏的行为是由玩家主动发起或偶然执行的。确实,有些电子游戏也采用传统的方式,但大多电子游戏不是这样的。在FPS中,如果玩家爆头得分在大程度上取决于运气,那么这类游戏也就不会这么火了。甚至电脑对手避开爆头的行为也不是随机的,而是受到复杂的AI的控制。

此外,当AI驱动游戏的活动时,受AI控制的电脑对手和障碍也不一定遵循玩家必须遵循的规则,即使他们存在于相同的游戏世界。这可能与许多游戏中的“商人”存在些许相似点,AI通常没有“回合”。此外,玩家不总是启动作用于游戏的AI程序,如果AI与骰子、下拉列表或事件面板一样,那么玩家就会总是启动AI程序。他们只会在虚拟世界的一个环节中到达AI的权限。至少驱动电子游戏的机制与传统模式是相当不同的。

(我意识到人们打开游戏和按下开始按钮,这就激活了AI。但启动游戏不属于游戏环节,而将棋盘放到桌面却是游戏的一部分。)

Ferrari将虚拟世界解释为只是一种“材料,而不是传统的规则执行。”当然,关卡的边界和它的物理现象及其他条件可以算是一种规则执行。但是,有些游戏的关卡没有边界。玩家角色可以一直往前跑(或至少可以跑很久),脱离游戏的活动,变成无形状的棕色物体或不断地重复背景,而不会被游戏制止或惩罚。这几乎总是由设计师的疏忽导致的,但它确实突出了设计上的差异。游戏玩法发生的世界或关卡不只是一套具体的规则,还是一个游戏可能产生的虚拟空间,而规则是不产生空间的。因此我们才有了“沙盒游戏”和“开放世界”这些术语。就意义比较而言,这种游戏世界无法达到棋盘的程度。更别说奖励、作弊码、额外的命数、变化的获胜条件、积分、秘密区域、难度设置、掉落物品等等,这些都是电子游戏处理游戏世界和规则的独特方式。

这些能构成“形式”上的差异吗?我不知道。但如果你把条件再放宽,那么几乎所有东西都可以说是一样的。所以,把我的身体跟黑猩猩的身体相比,差异还没有大到让另一个人说我们之间存在形式上的差异。我们各自的行为差异才能暴露出更显著的区别。

我没打算藐视Ferrari的话,或者为了解释它而解释它。我也不打算区别所有类型的游戏。我写这篇文章的目的是,表明这个世界上存在各种不同的游戏——甚至不同的电子游戏也具有不同的关卡基础。我希望能让读者意识到传统游戏的特征不应该约束电子游戏和故事相关的媒体的特征。虽然二者之间有时候确实存在约束关系。无论如何,我没有声称我解决了传统游戏与电子游戏的争论问题。如果我想的话,我只会把形势弄得更糟。

故事的独立性

Ferrari和Will Wright似乎都认为,电子游戏的故事既多余又低劣。Wrigh表示,带故事的游戏“不是我喜欢玩的游戏”。Ferrari在与Tom Bissell的交流中无数次表达了类似的观点,不过这不是他写作的唯一目的(他的文章涉及其他话题,深刻又有趣)。然而,Ferrari确实引用了一个非常有趣的电子游戏案例。提到任天堂的经典著作游戏《Chrono Trigger》时,他说:

我承认我仍然将《Chrono Trigger》和《Earthbound》当作我最喜欢的游戏,尽管这两款游戏都具有明显的日式RPG的故事导向型特点。但我已经很长时间没玩这两款游戏了,因为我知道现在重返游戏只会让我因为意识到它们的叙述缺点而产生失落感,而这种失落感又会取代我对它们的故事理想化之后的美好记忆。

《Chrono Trigger》其实是一个非常好的讨论案例,因为任何其他媒体都无法让它的故事叙述达到相同的成功。公道地说,它是一款低龄向的游戏——它的受众已经长大了,成了现在的主流玩家中的一员。所以十五年之后再看《Chrono Trigger》,其中的某些内容不免有些造作和陈腐。任何游戏都是不完美的,但我认为《Chrono Trigger》确实一度是“电子游戏讲好故事”的典范之作。也就是,它的故事只有以它的方式讲述才能完美。

玩家第一次进入Zeal的魔法王国,是所有电子游戏的叙述的一大惊喜。为了描述游戏如何引发这种惊喜,我将从叙述和玩法两点出发,尽量还原玩家在这款游戏中的体验。

首先,游戏必须提供让玩家抵达Zeal的情境。在让玩家通向Zeal的五六个小时的游戏时间里,主要的任务就是寻找和打败Magus——一个企图毁灭世界的魔法师。他的卡通风格的城堡是一个经典的地下城,并且游戏的大部分挑战也是地下城游戏式的。

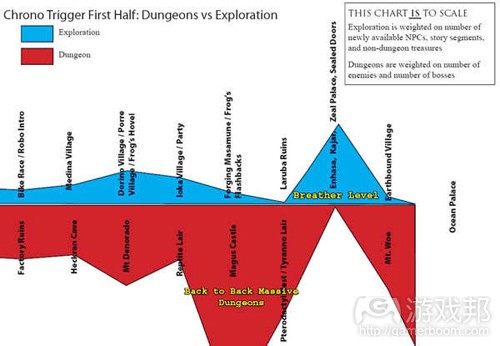

(Magus的城堡之前的一个地下城共有33个敌人,即32个普通敌人和1个BOSS。而Magus的城堡包含118个敌人和4个BOSS;Tyranno巢穴包含65个敌人和2个BOSS,仍然比前面的地下城多。Tyranno巢穴紧接着Magus的城堡。详见下图)

玩家角色通过打败大量强大的敌人而获得更多经验。这通常是角色第一次获得更高级的战斗技能的时候。华丽的新攻击技能其实对增加地下城难度的BOSS战也是必需的。

与Magus的战斗高潮安排得相当巧妙,至少按90年代的游戏机游戏的标准来说。Magus有结界,会吸收伤害,如果玩家不谨慎,可能会被结界反弹的一半伤害打到。玩家头一两次打Magus,基本上打不过,得重来。另外,Magus的进攻(就当时而言)画面非常震撼人心,所以游戏的玩法确实让玩家觉得Magus就像故事所说的那样,是个难对付的敌人。作曲家Yasunori Mitsuda的音乐与经典的最终一战配合得天衣无缝。

走出Magus的城堡后,玩家很快就来到另一个巨大的地下城。结果是,被打败的Magus居然不是最终BOSS;游戏有10小时,所以这个消息不会让人觉得惊讶。这次玩家面对的是另一座古老的地下城,Tyranno巢穴的难度比Magus的城堡来得大。扫清巢穴的普通敌人后,玩家终于见到另一个BOSS:喷火霸王龙。这一战,虽然不一定像Magus之战那么复杂,但时间更久。事实上,十五年后再次回顾这一场战斗,显然这个BOSS与其说是生存的战斗,不如说是耐力的考验。这场考验之所以让玩家觉得漫长,是因为在这三四个小时的游戏里,玩家除了在危机四伏的地下城里探险和与最强大的BOSS战斗,就什么事也没做。

BOSS打败了,故事的结局就是,天崩地裂,地下城塌陷成一个巨大的坑,这个坑是将玩家引向未知年代的传送门。角色只是疑惑自己身在何处。

然后,一片死寂。

接下来就是整个游戏的金钱时间。在这20分钟里,没有强制的战斗,没有强制的过场动画,最重要的是没有任务。玩家没有前进的方向。这太怪异了,因为玩家经过了一座又一座地下城,一场又一场的战斗,后者都比前者更加突出剧情线索。所以肯定还有另一座地下城?还有未达成的目标?游戏直到这时才暴露真相。

在第一分钟,玩家既兴奋又困惑,部分是因为终于从小洞穴里出来了,另一部分是因为发现自己到了另一个完全陌生的地方。在屏幕上只能看到冰天雪地,原来是进入了冰河世纪,没有文明存在——所以当然也没有地下城。在地图上唯一能进入的地方就是一座标着“Skyway”的神秘的建筑。游戏没有告诉玩家那是什么或通向哪里。当然,别无去处的玩家只能踏上发光的平台,任平台将他们带到Zeal的王国。

描述Zeal一定程度上是没有意义的,因为这个词是被杜撰出来形容一个场景烂俗的地方:飘浮的大陆、乌托邦、魔法王国。现在电子游戏技术的飞速发展当然使十五年前的Zeal画面显得落后。(我认为仍然是不错的,不仅技术强悍,而且制作精良。)如果说有些可惜,那也是不可避免的。但这个地方的天才之处不再于它的图像,而是它没有使用扫描整个王国的镜头,没有NPC莫名其妙地跑上来向你背诵冗长的介绍,没有任务窗口弹出来告诉你该去哪里该做什么;只是让玩家无拘无束地漫步于这个神奇的梦幻国度,它的存在是玩家绝不可能预料到的——甚至前个小时以前。

玩家可以与NPC交谈,NPC会介绍Zeal和它的历史、文化、人民——间接地将这个王国与故事主线联系起来。你可以购买装备、在美丽的城市里寻找密室、在隐蔽的地方寻找珍惜物品。甚至可以读书,如果你找得到的话。通过适当的安排,玩家又见到神秘的大师——这是玩家已经见过的角色。到处都是Zeal的皇家花园,过了几分钟,玩家意识到他们曾经见过:它出现在所有“被神秘力量封印”的门上。许多之前联系不上的想法都在玩家头脑中串起来了,玩家这才发现这个故事远比他们之前想象得庞大。

这是电子游戏叙述的一个精华部分,在剧情和游戏两方面都达到极致。这是电子游戏最有特点的地方——一个独立的虚拟世界,让玩家可以按自己的方式继续故事。虽然这部分归功于出色的美术、剧情和音乐,但我们很难忽视作为游戏世界中的一个关卡的Zeal发挥了怎样的作用。至于玩家第一次来到Zeal时感到困惑,首先是因为玩家从来没有想到有这么一个地方存在,其次是因为玩家刚刚从巨大的地下城里挣扎出来。Zeal就像一个“喘息关卡”,打断了千篇一律的地下城玩法,让玩家自由探索游戏的目标(神秘物品)和剧目的目标。就这点看来,Zeal是游戏的一个中心。Magus的城堡和Tyranno巢穴不过是游戏前半部分的最后考验,而Zeal则是游戏高潮开始以前的中场休息。

故事的结构和世界

我喜欢《Chrono Trigger》中的Zeal,觉得它是建筑的艺术。从根本上说,这种建筑的存在是因为人们喜欢探索美丽的空间。建筑的作用不只是让建筑安全或实现功能——那是建筑师和承包商的工作。建筑在改变空间,以反映情绪、气氛或与空间有关的理念方面发挥自己的作用。

可以说玩家并不需要Zeal这种喘息关卡;他们想休息时大不了关了游戏机。可以说用于设计和制作Zeal的时间和金钱本可以用来制作更复杂的玩法。但那无异于说,我们不需要这种建筑,我们只要简陋的避难所就够了。人们希望自己的房子美观,办公室整洁,餐馆高档,花园漂亮。在电子游戏中,设计师们是王国、文明和梦想的建筑师。我们怎么会不想让游戏充满精彩的故事,有趣的角色、幻想的城市和令人惊奇的迂回曲折?这些都是人们喜欢的东西——这些就是人们购买游戏的原因。

糟糕的电子游戏故事也存在,但它们不能代表游戏的未来。与其他人一样,我讨厌《战神》和《使命召唤:黑色行动》中轻率的暴行和大男子主义。然而,我不会将其作为反例批评所有电子游戏的故事。我想到的是,科幻游戏曾经(可能现在仍然)在“真正的”文学的批判下挣扎。作家Theodore Sturgeon为憋脚的科幻作品道歉了这么多年后,表示他认为如果你将相同的标准强加给所有作品,那么“90%的电影、文学作品或其他文化消费品都是垃圾。”所以如果优秀的AAA故事似乎寥寥无几,可能是因为好作品出得还不够多。特别是如果我们要判断什么“应该有”和什么“不应该有”,我们就需要考察更多故事。高价值的电子游戏故事仍然处于起步阶段,我们应该给予更多时间来体现它们的价值。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Architecture of Dreamsby

by Patrick Holleman

Although this site does not usually operate like a blog, I think it is worth responding as such to two recent articles about stories in videogames. The more important of those two pieces is the set of published letters exchanged by critic Simon Ferrari and author Tom Bissell. While their letters covered a number of topics pertinent to video games, one of the most striking things I read was that Ferrari felt he was unable to go back and play two of his favorite games from youth because his adult perspective on the low-quality stories in those games would destroy his fond memories.

One of the two games Ferrari cites as his favorite is the SNES classic Chrono Trigger. Chrono Trigger isn’t in the same esteemed place as Hamlet or Anna Karenina by any stretch of the imagination. As an adult, however, I can look back through 15 years and have a deeper appreciation for how Chrono Trigger’s designers manipulate the player’s expectations, both in terms of what they expect from the story and what they expect from the game as a series of levels. (There’s actually a graph included with this post that illustrates exactly how they accomplished what I’m talking about.) In doing so they created one of the most effective mid-story surprises in all of videogames without resorting to cheesy plot twists. What’s more, they did it in a way that could only be done in a videogame.

But rather than start with the response and fill the first page with spoilers, let’s start with the critical position Ferrari might be coming from when he says this, and go from there.

There are Games, and then there are Games

Will Wright recently said that games are not the right medium for telling stories. Now to be fair, this was probably something influenced by his media people as a way to freely publicize his new TV show in major venues like CNN.com, that ran the story. Still though, he’s Will Wright and I’m certain he had some say in which of his words were printed. Wright offered an alternative: “Video games are more about story possibilities.” I’m not sure how something can be about a possibility, unless you’re talking about an insurance policy. Maybe this is just a concession on his part so that he doesn’t sound too harsh.

If he’s saying that games should not tell stories, my immediate reaction is “or what?” What will happen if games tell stories? Of course that question is moot because games already do tell stories. Many games even tell stories in the much-maligned cutscene. And yet many of those games do perfectly well in the marketplace, which seems to justify their existence. Is Wright saying the buying public ignorant of where the “real” games that don’t tell stories are sold? Or does the buying public simply have poor taste? Those points are moot too because, as I said, games that tell stories exist, and they’re popular. And I can’t imagine that even Will Wright can stop the people who make story games from earning their living that way.

I think there is an underlying issue here that motivates Wright and other people in the gaming industry to say that games should not tell stories, or at least not in the way they do now. The issue is that Wright sees videogames as an extension of traditional games, which don’t have stories in any conventional sense. (By traditional games I mean chess, poker, Monopoly, etc.) And I agree that saddling Stratego with a story would be a bad idea. There are “tabletop” games that have stories, like Dungeons and Dragons, but tabletop role-playing games are very different. Right?

As I mentioned at the beginning, another well-known figure in the field of gaming commented on this recently. Critic Simon Ferrari said,

I hold that there are few formal differences between the design of analog games and digital games, while nevertheless recognizing that there are financial differences, cultural differences, differences in taste, and differences in apparatus—for instance, the encyclopedic and procedural properties of the computer allow for the storage and retrieval of complex game states; dynamic or realtime play; and the material, rather than conventional, execution of rules.

Ferrari seems to be saying that although the apparatus of the game has changed, the fundamental properties of games have not changed; they just look a bit different.

I think this is perhaps where the break occurs between people who are interested in the storytelling potential of games and those who aren’t.

The way that Ferrari connects historical games to the present (via writing and scholarship about games) is through ancient China and Greece, and their “critiques and celebrations of play, sport and games.” I think that right there he has incidentally highlighted an important distinction. Sports are games, too. When Mohammed Ali taunted George Foreman in their 1974 fight—with right hand leads and mocking encouragement shouted at him through his mouthpiece—he was employing a classic game strategy: baiting your opponent. The same thing can be done in chess or poker with equal success. And yet if you look at the best sports writing, it emphasizes things that are very different than the best game writing. I can’t think of any scholar of games who proposes that we eliminate the physicality of sports or the use of instant replay by large refereeing crews because they’re not like traditional games.

In the same way that sports and traditional/tabletop (for lack of a better term) games are both different kinds of games, so too are videogames different. So when Ferrari says that he sees no formal differences in videogames and traditional games, I’m not sure how he accounts for artificial intelligence and the discrete simulated world. In a traditional game, the action of the game is driven either by the players or by chance. True, some videogames use chance in traditional ways, but many videogames do not. If a player’s ability to score a headshot in a first-person shooter were dependent mostly on chance, the game would lose much of its audience. Even when computer opponents haphazardly avoid the headshot, they’re not acting in a random way; they’re being controlled by a complex artificial intelligence.

Beyond that, when artificial intelligence drives the action of the game, the computer opponents and obstacles controlled by artificial intelligence are not always bound by all the same rules that the player is, even though they exist in the same playing field. That might have some similarities to the “dealer” in many games, but then again the AI isn’t usually taking a “turn”. Moreover, the players do not always initiate the AI programming that drives a game as they would if the AI were the equivalent of dice, a spinner or an events deck. They simply arrive within the AI’s purview in a section of the simulated world. At least in that the mechanics that drive the videogame are fairly different from traditional models.

(I realize that people do turn the game on and press the start button, which activates the AI. But activating the game is not a play action any more than putting the chess board on the table is a play action.)

Ferrari explains the simulated world as merely a “material, rather than conventional, execution of rules.” Certainly the bounding walls of a level and its physics and other conditions can be an execution of rules. But then again, there are levels in some games that don’t have boundaries. The player character can run forever (or at least for a very long time) away from the action of the game into a shapeless brown blur or endless repeating background without being stopped or penalized. This is almost always an oversight on the part of the designers, but it does highlight a difference in design. The world or level in which gameplay takes places is not merely a set of reified rules, it is a virtual space in which play, according to rules that don’t create the space, is possible. Thus we have terms like “sandbox games” and “open world.” That world is not enough like a chessboard for the comparison to be meaningful. And of course is to say nothing of bonus stages, cheat codes, extra lives, varying victory conditions, high scores, secret areas, warps, difficulty settings, loot drops, etc which are all unique ways that videogames address their world and their rules.

Does any of this constitute a difference in “form?” I don’t know. But if you generalize broadly enough, almost anything can be said to be the same. The differences in the form of my body and that of a chimpanzee are not so great that a third party couldn’t say we have no formal differences, if they really wanted to. The differences in our respective behaviors would reveal a more telling distinction.

I do not mean to make light of what Ferrari said or take it out of context only to dismantle it for the sake of doing so. Nor do I mean to make the final distinction between all the various kinds of games that exist. The purpose of writing this is to show that there are different kinds of games— indeed there are even different kinds of videogames that differ at a fundamental level. I’d also like to raise some amount of doubt about the notion that the traits of the traditional game should govern the traits of videogames, story-related or otherwise. Sometimes they do, but sometimes they don’t. Whatever the case, I do not claim to have solved the problem and cleared everything up. I think that, if anything, I have only muddied the waters.

Stories that Belong Nowhere Else

It seems that Ferrari and Will Wright are of a common mind that videogame stories are either superfluous or simply bad. Wright says of games with stories, “That’s not the kind of game I like playing.” Ferrari expresses similar sentiments numerous times in his exchange with Tom Bissell, although saying so was not the sole purpose of his writing. (The article had other topics, and was generally thorough and an interesting read.) Ferrari does, however, bring up a very interesting case in videogame stories. He says of the SNES classic, Chrono Trigger:

I’ll admit that I still count Chrono Trigger and Earthbound, two obviously story-heavy JRPGs from the SNES era, among my favorite videogames. But I haven’t played those two videogames in a long time, because I know that returning to them now would only replace my nostalgic idealization of their stories with a number of depressing realities about their narrative shortcomings.

Chrono Trigger is actually a great example to discuss because its narrative could not be achieved in any other medium with the same success. To be fair, it was made for a younger audience—indeed it was made for the young people who grew into the mainstream audience of today. So some of what Chrono Trigger has in it looks a bit saccharine and trite from a distance of fifteen years. No game is perfect, but I’d contend that Chrono Trigger has one moment that really defines what it means to tell a great story in a videogame. That is, it tells a story that really couldn’t be told as effectively any other way.

The player’s first arrival in the magical Kingdom of Zeal is one of the most effective surprises in all of videogames—narrative or otherwise. And to describe how the game pulled this surprise off, I’ll try to recapture the player’s experience of the game as best I can in a brief space, both from a narrative and gameplay point of view.

First it is necessary to establish some context about the events leading up to said arrival. The five or six hours of play leading up to Zeal have been primarily structured as a quest to find and defeat Magus, the archetypal sorcery-villain who is the creator of an eldritch abomination that will eventually destroy the world. His cartoonishly foreboding castle is a classic dungeon-crawl, and by far the most challenging portion of the game yet.

(The dungeons up until this point averaged about 33 enemies and one boss total, and the median number of enemies was 32. By contrast Magus’ castle contains 118 enemies and 4 bosses, while the Tyranno lair contains about 65 encounters and 2 bosses, still much larger than before. And the T. Lair appends to the end of the previous dungeon almost immediately. See the chart below for a visualization of this)

The player characters start gaining experience much faster from the masses of powerful enemies. Accordingly this is usually the point where those characters first earn their higher-level combat abilities. The flashy new attacks—and the fact that these attacks are also essential for the difficult boss fights—lend a sense of gravity to the dungeon.

The climactic battle with Magus himself is a fairly clever one, at least for a mid-nineties console game. Magus uses a shield that absorbs damage and has an attack that can wipe the player’s party out in one hit if the player is not careful. The first one or two times the player fights Magus, they stand a good chance of dying and having to reset. Moreover the attacks Magus uses are (for the time) quite graphically impressive, so the gameplay really reinforces the fact that Magus is as tough an enemy as the story says he is. Composer Yasunori Mitsuda’s soundtrack is at its absolute best right during this fight. It’s a classic showdown.

Very shortly after Magus’ castle, the player is thrown into another huge dungeon crawl. Magus, as it turns out, is not the real villain; the game is only about 10 hours long at that point so it’s not too much of a shock. The player winds up in the distant past next, faced with another crawl through the prehistoric Tyranno Lair, a dungeon about as challenging as than Magus’ castle. After battling through that dungeon, the player is confronted with another iconic villain: the fire-breathing dragon (in this case as a fire breathing tyrannosaurus). This fight, while not necessarily as tricky as the Magus fight, is much longer. In fact looking back on it, with fifteen years perspective, it is clear that this boss offered a test of endurance rather than a fight for survival. This test of endurance feels especially long because for the past three or four hours the player has been doing nothing but crawling through dungeons filled with enemies and fighting ever-more-difficult bosses.

After the boss is defeated, the eldritch abomination around which the story is centered introduces itself by falling out of the sky, blowing the dungeon to hell, and leaving a giant crater with a portal that sends the player onward to time unknown. The characters briefly wonder aloud where they are.

And then silence.

What happens next is the absolute money-moment of the entire game. For the next twenty minutes there are no mandatory battles, there are no mandatory cut scenes, and most importantly: there’s no quest. The player has no directions to follow. This is very disorienting because the player has just been through dungeon after dungeon, battle after battle, each one proving more climactic and more revealing of the plot than the last. Surely there is another dungeon close at hand? Some objective to fulfil? The game has been so clear about these things up until this point.

That first minute is as bewildering as it is thrilling, as the party emerges from a small cave to find themselves in a completely unfamiliar world. They enter into an ice age, with no civilization—and no dungeons for that matter—visible anywhere on the first screen. The only fully accessible location on the map is the mysterious building labled “Skyway.” There are no instructions on what it’s for or where it leads. Of course with nowhere else to go, the players step on the glowing platform that beams them up into the Kingdom of Zeal.

Describing Zeal is somewhat pointless since the words coined to describe places like it are largely reductive with overuse: floating continent, utopia, magic kingdom. The rapid progression of videogame technology has, of course, made Zeal graphically ancient. (I think it still looks good, because it was cleverly crafted, not just technologically robust.) That’s inevitable, if somewhat lamentable. But the genius of the place was not its graphics; the genius of Zeal is that never once is there an inescapable, sweeping camera shot that reveals the entire kingdom. Never once does an unavoidable NPC rush up to you and start reciting a lengthy exposition piece. Never once does a mission objective pop up and tell you where to go and what to do. The player is merely left to wander, uninhibited, through a marvelously persuasive dreamworld whose existence they never could have imagined—even half an hour ago.

It is possible to talk to NPCs and they will talk about Zeal, its history, its culture, its people—this indirectly ties the kingdom to the main plot. You can buy equipment, find secret chambers in the elaborate cities, and find a number of rare items in obscure locations. There are even books to read, if you look for them. The mysterious gurus—characters already encountered in the game are introduced in their proper context. The royal crest of Zeal appears everywhere, and after a few minutes the player realizes where they’ve seen it before: it’s present on every door that has been “Sealed by a mysterious force.” A large number of previously disconnected ideas click together in the player’s mind revealing the shape of a much larger plot than the player imagined they were a part of before this point.

This is an amazing moment in videogame storytelling, at both its most narrative and game-like. That which is most characteristic to videogames—the discrete simulated world—has provided a place where the player can play their way through a story. Some of this is art direction, clever writing and great music. But it’s difficult to overstate how well Zeal works as a level in a game. Upon first arrival there is disorientation because first, players never expected Zeal to happen and second, because players just crawled through a huge amount of dungeon. Zeal acts as a “breather level” that breaks up the monotony of constant dungeons, allowing the player to explore for both game purposes (secret items) and plot purposes. In that regard Zeal is the center point of the game. Magus’ Castle and the Tyranno Lair were merely the final tests of the first half, and Zeal is the intermission before the climax of the game begins.

Architecture and the World of Stories

I liken the presence of Zeal in Chrono Trigger to the art of architecture. Ultimately, architecture exists because people like to move around in beautiful spaces. The job of an architect isn’t to make a building safe or functional in a basic way—that’s more the job of the structural engineer and the contractors who build it. Architects do their work adapting the space to reflect a mood, an atmosphere, or even a philosophy that pertains to what the space is for.

It would be easy to say that players don’t need the breather level that Zeal affords them; why don’t they just turn the console off if they want a break? It would be easy to say that the time and money spent on embellishing and populating Zeal could have been spent on more complicated gameplay. But that’s the same as saying we don’t need architecture when what we’re really after is shelter. People like their houses to look nice, they like their offices to look impressive, they like their restaurants to look classy, they like their gardens to look cozy. In a videogame, designers have the ability to be the architects of kingdoms, of civilizations, of dreams. Why wouldn’t we want to fill those games with great stories, interesting characters, fantastic cities and surprising twists and turns? These are things that people like—these are things that people have demonstrated they will buy a game for.

Bad videogame stories exist, but they are not the only kind of story, and they don’t own the future of gaming. I am repulsed by the thoughtless brutality and machismo in God of War and Call of Duty: Black Ops as much as anyone else. I do not, however, take that as an indictment of all videogame writing. It occurs to me that science fiction once (and perhaps still) labored under the constant withering attacks of critics of “real” literature. The author Theodore Sturgeon, after decades of apologizing for bad science fiction said that he believed, if you apply the same standards to everything, that “ninety percent of film, literature, consumer goods, etc. are crap.” So if good AAA stories seem to be few, perhaps it is because a sufficient body of work has not been established. Especially if we are to judge what “should” and “should not” be done, we need more stories to examine. Videogame stories with high production values are young yet; give them time to show their value.(source:thegamedesignforum)

上一篇:论述游戏设计复杂性与成功的关系

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号