设计师应掌握用户玩游戏的主要动机

作者:Lewis Pulsipher

在某些情况下,设计师必须清楚为什么人们喜欢玩游戏。但是如果有人真正清楚这一原因,那么他们便足以因担任游戏顾问而大发一笔了。

没有人可以准确说出为何人们喜欢玩游戏,尽管一直有人尝试着做出解释。如果有人可以用80页的内容去定义一款游戏(即著作《Rules of Play》),我们又该使用多少篇幅去解释清楚为何游戏是有趣的?现在已经出现不少专门讨论这个话题的书籍,我希望在此结合我自己的经验并总结一些人们所提出的较不哲学化的观点。

游戏设计师总是会根据自己的判断去设计游戏。但是许多源自娱乐软件的案例却让大多数专家惊讶不已。为何如此多玩家会认为《模拟人生》或《块魂》很有趣?一个很简单的答案便是“当各种人在帮助你测试游戏时,你便能发现游戏中最重要的元素。”

不管你是如何看待游戏乐趣,或者不管你是否喜欢你的游戏,游戏测试能够真正反应出更多玩家对于游戏的看法。如果越多玩家喜欢你的游戏,那就证明你的游戏是有价值的。但是如果很少玩家喜欢,你便需要思考如何做出改进了。

不幸的是,电子游戏领域的开发者如果想在设计初期明确玩家真正想要的游戏,就不得不投入大量的时间和金钱。所以他们便需要真正弄清楚为何人们喜欢玩游戏这一问题。

需要注意的是我并未提到有关“有趣”的字眼——因为许多喜欢玩游戏的人并非认为自己体验到了游戏的乐趣。就拿国际象棋来说吧,人们可能会觉得它很有意思,很吸引人,但是却很少有玩家会用“有趣”去形容它。

“有趣”通常都是源于一些外部因素,包括对手的游戏态度以及环境等,而不是关于游戏本身。当玩家在玩一款棋盘游戏时他们能够欢呼大叫,尽情地体验游戏,但是却很少玩家会用“有趣”去描述游戏。

当然也存在一些能够用“有趣”去形容的游戏,但却并非所有玩家都喜欢玩有趣的游戏。甚至有些人还会认为这类游戏过于愚蠢且无聊。

什么是有趣的体验?

某些作者列出了一些玩家在玩游戏可能感受到的乐趣。而这一列表能够帮助我们进一步了解什么是有趣的游戏。

众所周知的便是来自Marc LeBlanc的总结:

感动—-以游戏愉悦感官

幻想—-以游戏模拟世界

故事—-游戏呈现不断发展的故事

挑战—-游戏是困难重重的载体

友谊—-游戏是社交框架

发现—-游戏是未被开发的领域

表达—-游戏是临时讲台

顺从—-游戏是一种简单的消遣工具

在2008年的Origins Game Fair大会上,Ian Schreiber(游戏邦注:《Challenges for Game Designers》的合著者)也阐述了他的乐趣版本:

*探索

*社交体验

*收集

*触感

*解决谜题

*进步

*竞争

如果让一组游戏玩家列出人们可能喜欢的游戏元素,那么这一列表中的大多数内容都将以某种形式出现在玩家的答案中。

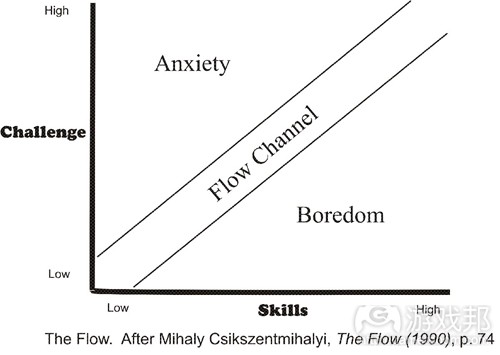

Raph Koster(在其著作《A Theory of Fun for Game Design》中)让我们注意到了Mihaly Csikszentmikalyi的研究,从而感受到什么是“最佳体验”。通过一系列著作描述,我们知道这位来自捷克的研究人员将自己的想法运用于生活中的一切事情,而我们也可以将这些想法运用于游戏。Csikszentmikalyi致力于研究“人类体验的积极性——乐趣,创造性以及生活中所经历的整个过程,我将其称为心流(Flow)”[Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience(1990),p. xi]。

而如果是从游戏目的来看则变成:当人们在面对适度挑战时便会感受到最佳体验。换句话说,如果玩家面对的内容太过简单,他们很快便会失去兴趣。而如果挑战过于复杂,他们最终也会产生挫败感和焦虑感。完美的体验是指基于玩家的技能水平去创造挑战,并随着玩家能力的提高而不断提升挑战难度。也就是让玩家处于“心流过程中”。

电子游戏在分配挑战级别是更是突出——不管是基于不同难度设置而进行适应性程序设计还是逐渐提高游戏关卡的难度。而在非电子游戏中,挑战的级别便需要做出调整,因为玩家所面对的对手也会像玩家一样不断提高能力,或者玩家会找到更加优秀的对手与之对抗。在非电子类角色扮演游戏中,如《龙与地下城》,将由裁判(也就是游戏中的地下城主)去分配挑战级别。就像新手不会遭遇火巨人但却会频繁遇到半兽人,而资深玩家则会不定期遇到古老且可怕的龙,这时候他们不会再把半兽人当一回事了。虽然从某种意义上看来这是一种人为的行为,但是它却能让游戏变得更加有趣。

趣味因人而异

尽管这些分类和方法能够帮助我们更好地进行思考,但是在游戏乐趣中这些元素还具有范围因素,即有些人认可某些元素,但也有些人反对这些元素,而大多数人还是保持着中立态度。有些范围是相互重叠的,也有些人对于一些更基本的元素持有不同观点。

以下将是我要讨论的一些元素(当然不是决定性元素):

实现梦想vs.突现(故事主导vs.规则主导)

故事/叙述vs.下一个/新环境中会发生什么

古典vs.浪漫

长远规划vs.对环境改变的反应/适应

社交vs.竞争

娱乐vs.挑战

幻想/放松vs.精通游戏

旅程vs.目的地

实现梦想vs.突现(故事主导vs.规则主导)

许多人都表示电子游戏能够帮助玩家实现梦想:但是游戏设计师想要帮助玩家实现的梦想到底是什么?在许多游戏中,梦想(如果真的存在的话)其实非常模糊。在象棋,西洋棋以及其它抽象游戏,如《俄罗斯方块》中玩家可以实现什么梦想?玩家是否真的梦想控制一个国家长达1千年,就像在《History of the World》,《帝国时代》或者《文明》中那样?

当然也有许多电子游戏让玩家能够体验到他们在现实世界体验不到,或不敢体验的内容。就像居住在幻想世界中便是射击游戏和动作类游戏的一大组成要素。

这种类型的游戏可以称为“故事主导”。如果游戏的目的是帮助玩家实现梦想,那么肯定会涉及一个故事,而游戏便是这一故事的表现形式,不管故事多么简单(就像梦想也有简单和复杂之分)。

而范围的另一端便是“规则主导”游戏,这包括各种传统游戏,如象棋和围棋等。游戏玩法是基于规则而出现,而非遵循游戏故事(因此这种游戏也被称为“突现”游戏)。游戏拥有一整套规则,而游戏过程更是通过玩家采取各种方法而出现于规则之上。棋盘游戏和纸牌游戏便属于规则主导,而许多大受欢迎的电子游戏以及角色扮演游戏则属于故事主导。

规则主导游戏总是涉及多边对象,而角色主导则只包括游戏双方,即玩家和计算机(游戏邦注:或者是像《龙与地下城》这类型游戏中的裁判)。

比起非电子游戏,电子游戏,特别是AAA游戏更加突出角色设定。即玩家能够做各种自己幻想中的事,特别是在现代AAA游戏中玩家的感受会更加真实。另一方面,“休闲”电子游戏更趋于规则主导,像棋盘游戏和纸牌游戏。

Sid Meier最近对“突现”游戏进行了描述:

“让玩家在游戏中感受到乐趣这点非常重要,”Meier指出设计师需注意不可让游戏玩法偏离正轨,“我们的理念是让游戏设计师站在幕后,让游戏故事能够根据玩家的决定而发展。”(Chris Faylor,Shack News,2008年2月20日)

故事vs.新环境

有些玩家喜欢遵循着故事发展而发展,但是也有些玩家讨厌被牵着鼻子走。然而他们还是面对着相同的游戏体验。这种情况通常是出现在“线性”游戏和“沙盒”游戏的比较中。

基于线性表达(就像书或电影中那样)我们总是很容易创造出一个强大的故事,所以最强大的故事主导游戏便属于线性游戏。

比起线性游戏,沙盒游戏的重玩价值更大(在其它条件相同的情况下),因为线性游戏中只存在一两个故事。

沙盒电子游戏,如《侠盗猎车手》和《刺客信条》便回归到早前的电子游戏风格中,即游戏不再突出或出现任何特别的故事。

角色设定游戏未必就是线性游戏或故事主导游戏。许多电子游戏的鼻祖——《龙与地下城》(纸上版本)可以采用这其中的任何一种模式。地下城城主能够构思出一个故事并设定一场冒险,让玩家遵循着这一故事而前进(线性方法)。或者城主还能够设定一个适当的挑战环境并等待着结果——而不再预测玩家将如何进入这一环节也不再基于任何特定点去引导玩家前进(沙盒模式)。而不管是基于哪种方式玩家都将遭遇相同的冒险,并将衍生出一个不同的故事。比起电子游戏,纸上游戏更适合采用沙盒模式,因为人类裁判比计算机更擅长调整游戏的进程。

作为玩家,我很讨厌侧重故事的《龙与地下城》,因为这意味着游戏会强迫我做各种我不想做的事。但是也有许多玩家更喜欢受故事驱动的游戏类型。当然了,在突现游戏中也存在故事,而在故事游戏中也有策略和战术。我只是重点阐述主导元素罢了。

但是可以肯定的是,许多玩家都具有很强的倾向性,喜欢某一种类型便会非常讨厌另一种类型。

古典vs.浪漫

在那些胜负欲望非常强烈的玩家(当然不是所有玩家都属于这种类型)中共存在两种基本的游戏类型。追溯到19世纪关于音乐,绘画以及其它艺术形式的区别,我将这两种基本类型称为古典与浪漫。

古典玩家总是会由内而外去理解每一款游戏。他们总是希望掌握抗击对手(或计算机)任何行动的最佳方法。他们做任何事都不会只是想当然,甚至会关注于那些可能不是很重要的细节(但是在某些情况下却是非常重要)。古典玩家热爱冒险,但也会仔细评估各种冒险的结果。他们不喜欢不必要的冒险。比起快速但却没有胜算的行动,他们更愿意选择缓慢但却稳赢的挑战。他们一直在避免过于谨慎,唯恐被别人轻易看穿。在每一轮游戏中他们更希望逐步扩展自己的最小收益,而不是通过快速行动或攻击别人去获得大量收益(这种选择的最终结果也有可能不如最初的情况)。

有些人将其称为“极大极小”游戏类型。我不确定在游戏环境中“极大极小”是否等同于“古典”,但是它们肯定是两个非常相近的内容。并且可以肯定的是极大极小内容总是会变成古典游戏类型。

球迷中流传着一种说法是,失误最少的团队便是最优秀的团队,而其它队伍便只能败在自己手上了。所以对于古典玩家来说,他们会更加专注于减少错误而不是寻找最佳妙计。

另一方面,浪漫玩家则会不断寻找能够给予敌人致命打击的方法,不管是心理上还是身体上。他们总是希望让敌人相信其失败的必然性;在某些情况下,一些势力尚存的玩家如果在心理上遭遇浪漫对手的沉重打击时,他便会在其面前服输。浪漫玩家会为了打破敌人的计划并创造出对手不熟悉的游戏过程而进行冒险。他总是不断地寻找获得更大收益的机会,而不会满足于扩展最小收益。他喜欢出乎意料的行动,尽管这种行动总是具有风险性。

象棋更倾向于古典游戏而扑克则更倾向于浪漫游戏。但是即使采用相反的风格这些游戏玩法也不会受到影响。

因为许多电子游戏都允许玩家能够保存当前的位置并体验不同的策略,所以浪漫类型应该更受电子游戏玩家的青睐。

长远规划vs.对环境改变的反应/适应

有些人喜欢提前规划,事先思考各种选择并决定最佳前进道路。也有些人喜欢在事件发生后才做出回应,并努力适应变化。象棋和西洋棋便鼓励玩家进行长远规划。而《大富翁》则因为具有随机的移动机制以及两名以上的玩家,所以更具有适应性。玩家越多便意味着游戏的不确定性越明显,所以不确定性是适应性游戏玩法的核心内容。因为不清楚对方会出什么牌,所以扑克具有适应性,但是如果双方玩得越深入,那么最厉害的玩家便能够利用对手的个性而“虚张声势”。受纸牌驱动的战斗游戏便着重强调适应性:玩家只能基于手上所拥有的纸牌行动,并且他们永远都不会知道自己和对手将获得什么牌。

总之,完整的信息游戏有助于玩家进行事先规划,但是随着不确定的增加,适应性将比规划更加重要。出于各种原因,电子游戏玩家总是更倾向于选择适应性。

社交vs.竞争

派对游戏玩家是社交家的缩影。许多欧式棋盘游戏玩家和休闲电子游戏玩家便属于这种类型,甚至在竞争游戏中他们也拒绝向别人发动进攻。他们之所以会玩游戏只是希望与具有相同兴趣的玩家进行交流,所以他们并不在乎是否能够打败对手。而竞争游戏玩家则是那些以获胜为目标的人。

社交体验的有效性非常重要。非电子棋盘游戏和纸牌游戏通常都具有社交体验;而电子游戏的社交性也越来越明显(例如大型多人在线游戏和任天堂游戏),但却仍然侧重于玩家的单独行动,即玩家只能带着自己的想法和梦想进行挑战。

非电子角色扮演游戏便具有社交性,并且比起竞争游戏更加强调合作。

娱乐vs.挑战

提到游戏我们总是会联想起竞争或挑战,即玩家间在此相互对抗。但是《龙与地下城》改变了这种传统的看法,即玩家与游戏中的“坏人”展开对决,并且由地下城城主负责调停。这是一种合作性游戏,尽管其中也不乏挑战元素。

有些游戏甚至完全排除了竞争性并减少了挑战难度,变成是完全基于娱乐体验(而非竞争体验)的游戏(当然了,许多家庭游戏便是作为一种娱乐工具——尽管其表面看来是竞争游戏)。许多人会支付60美元(或20美元或5美元)去体验游戏所带来的乐趣而非挑战。尽管如此还是存在许多富有竞争性的玩家和游戏。就像《孢子》对于硬核玩家来说“过于简单”,但是对于大多数休闲玩家来说它却极具挑战。很明显竞争游戏是一种娱乐而非挑战。

从某种意义上看,任何游戏都能够具有娱乐性也能够具有竞争性,但是设计师应该仔细思考其真正的侧重点。因为人们在玩游戏的时候总是“不愿意进行思考”,所以许多电子游戏都用“身体挑战”(游戏邦注:如平台游戏中的跳跃,或射击)替代了心理挑战。对于设计师来说他们更容易基于玩家的需求将身体挑战转变为娱乐体验或挑战体验。

与别人在线对阵总是具有挑战性。而面对面竞争通常更具娱乐性,因为这时候的我们更容易了解对手。

某些谈论过这一主题的作家都认为,女性玩家更看重游戏的社交性和娱乐性,而男性玩家则更加青睐挑战和竞争。

放松vs.掌握

上述内容都是关于将玩游戏当成是一种实现梦想,或者掌握游戏技巧的方法。而后者能够让玩家感受到自己的重要性和存在感,所以更能吸引青少年玩家的注意。游戏总是会通过不同难度关卡而提供给玩家这两种感受。

不幸的是,如果游戏过分强调技能掌握,玩家便有可能做出欺骗或其它非社交性行为,并破坏所有玩家的娱乐体验。

也有些玩家并不看重自己是否能够精通游戏。玩家的态度会随着时间的发展而改变,当玩家逐渐成长并遭遇更多现实世界中的挑战和责任时,他们便会趋向放松。这时候对于玩家来说掌握游戏便不再重要了。

旅程vs.目的地

老一代人总是希望能够享受整个游戏过程——即使他们的主要目标也是赢得游戏。而年轻人则对目标更有兴趣,对他们来说“赢得游戏”比旅程更重要。当然了,游戏也必须具有足够的挑战性,这样才能让那些“带有目标性”的玩家获得真正的成就感。

这也等同于“发生了什么”vs.“结果怎样”。有些人玩游戏是为了掌握接下来会发生些什么。但是也有些人却只对结果感兴趣。他们甚至会跳过游戏的前面内容而只玩结果。

我曾经听过一个年轻人(写了两本关于代沟的书籍)描述他们这一代(Y一代或千禧一代)人总是喜欢使用作弊码直接跳到游戏的最后阶段,“赢得”游戏并对此感到满足。“我赢了游戏,难道不是吗?”这让我这个在婴儿潮时代出生的人倍感惊讶。“为什么你们要用欺骗的手法玩游戏?”他微笑地答道:“我们只是在收集研究的成果而已。”对此我摇了摇头。即使到了今天我还是不能理解这种想法,但是我却能清楚许多玩家将目标看得更重要这一事实。我想游戏设计师都必须清楚这一点。

以下是关于这种现象的另一种表现:

“事实上游戏并没有结果[100个关卡随机重复着],但是雅达利对于电子游戏的看法却与当今开发者的看法有所不同。雅达利将《Gauntlet》当成一个过程,它是为了自身而发展,且不会达到任何结果。在玩家耗尽自己的生命前,这种冒险将会一直持续下去,可以说他们的任务结果遥遥无期。

在过去几年里我一直与其他人一起在玩《Gauntlet》这款游戏。在他们知道游戏没有结果前,他们的目的只是努力获得生存。毫无疑问时间改变了他们的想法。”(John Harris,《Game Design Essentials: 20 Atari Games》,Gamasutra.com,2008年5月30日。)

基于游戏设计经验,我认为不管出于何种原因女性总是对旅程更感兴趣,而男性则更看重目的地。

所以我们可以推测,具有级别上限(这是一种标准,因为我们很难设计一款没有级别上限的MMO)的MMO适合那些目标性玩家,因为游戏中存在真正的目的地:最高级别。同样的,像《最终幻想》等RPG也能够吸引这类型玩家的注意,因为游戏故事的结果便是目的地。在早前的RPG中,不管是最初的非电子类还是一些早前电子游戏,游戏都拥有开放式结果。也就是不存在特定的目标。

最新版本的非电子游戏《龙与地下城》(2008年发行的第四版)便拥有一个明确的结果。也就是当角色到达第30级别时他便可以隐退了,而不像第一版那样玩家角色永远不可能到达最高级别(当然不是第30级!)。

我将使用一些额外的观察结果做出总结。

逃避现实?

实现梦想其实就等同于逃避现实。不管你承不承认,许多游戏都具有强烈的逃避现实元素,如果游戏的梦想味越重,其逃避现实的倾向也就越明显。这对于非成人玩家来说尤为重要。就像一名青春期男性的消遣方法便是玩射击游戏:

*玩家能够在此扮演与现实中不同的明星,“大男人”形象。

*玩家可以不受任何伤害而体验到刺激感(甚至是死亡)。

*游戏中总是存在着通向成功的方法——例如试错法,因为不管你是否死亡了都不重要。

*游戏不仅允许玩家相互竞争,还鼓励这种竞争。

*游戏中存在着一个明确的结构;现实生活中那些不确定性元素都不会出现在这里。

*年轻人也可以在此控制局势的发展,并且他们也可以持有挑衅和急躁的态度。

对于那些在现实生活中受到种种约束的青少年来说,这里便是天堂。游戏设计师必须意识到游戏中的这种逃避现实元素,即使他们设计的游戏不带这种特性。

个性

游戏玩家的个性也是多种多样。最常见的分类是将人类归为16种个性,就像在Myers-Briggs性格分类指标(游戏邦注:MBTI,是性格分类理论模型中的一种)以及David Keirsey的作品(如《Please Understand Me》)中所阐述的那样。这些原理都是源自Carl Jung的理念,甚至可以追溯到更早前的“人的四种气质”(来自希腊)这一观点。

同时我们需要意识到,拥有不同个性的人会做出不同的选择,会采取不同的方法去收集信息,也会对挑战做出不同反应。个性是从人们幼年时期便逐渐形成的,很难再发生改变。就像有些人在作决策前拥有更好的状态,所以他们便会选择先收集更多信息并推迟作决策的时间。而有些人则是在做出决策后更加信心满满,所以他们也会以不同方式去做决定。前者是通过学习的方法去做决定,但是这却违背了决定的性质。同样的,就像有些人更依赖逻辑,而有些人更依赖直觉。并且这种区别将严重影响着他们对于游戏的看法,甚至将决定他们是否愿意玩游戏。Keirsey表示不同职业会吸引不同个性的人,而我们也想知道游戏是否只能吸引这16种类型个性中的一部分人?

缺少经验的设计师必须清楚自己与玩家并不相同,所以他便需要自己决定游戏的目标方向和理念。任何游戏都不可能一开始便赢得各种玩家的欢心,因为玩家玩游戏的原因也总是多种多样。

游戏邦注:原文发表于2008年10月14日,所涉事件和数据均以当时为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Why We Play[10.14.08]

- Lewis Pulsipher

At some point designers should know why people like to play games. Yet if anyone truly knew this, he or she would become rich as a consultant.

No one can exactly describe why people like to play games, though many have tried. If an author can spend 80 pages just trying to define what a game is (Rules of Play), how likely are we to define why games are enjoyable? Entire books have been written about this subject — in this article, I summarize the less philosophical reasons people have suggested, and add some from my own experience.

Game designers make their best judgments about why people like to play, and then design accordingly. Yet there are many examples of software entertainment that surprise most experts. Why is The Sims so enjoyable for so many people, or Katamari Damacy? In the end, a simple answer to this question is “What matters is what happens when a large and diverse set of people play test your game.”

No matter what you think about enjoyment of games, no matter whether you enjoy your game, the play test reflects the reaction of a wide variety of players. If enough of them like it, you probably have something worthwhile. If not enough of them like it, you need to change it.

Unfortunately, in the video game world it costs so much time and money to get to the point of playing the game that we really need all the help we can get while doing the preliminary design. A practical discussion of why people enjoy playing games is therefore a worthwhile endeavor.

Notice I haven’t used the word “fun” — that’s because many people who enjoy playing games would not call them fun. Take chess as an example. It can be interesting, even fascinating, but many chess players do not describe it as fun.

“Fun” usually comes from external factors, from the attitudes of the people you play with and the environment, not from the game itself. People can laugh and shout and have a good time when playing an epic board game, even though most wouldn’t describe the game itself as fun.

There are certainly games meant to be “funny,” but not every gamer enjoys playing a funny game. Some think they’re silly and boring.

What is Enjoyable?

Some authors have made lists of the kinds of enjoyment people can have while playing games. Such lists are useful to remind us of the details of enjoyable gaming.

The most well known is from Marc LeBlanc:

sensation — game as sense-pleasure

fantasy — game as make-believe

narrative — game as unfolding story

challenge — game as obstacle course

fellowship — game as social framework

discovery — game as uncharted territory

expression — game as soap box

submission — game as mindless pastime

At Origins Game Fair 2008, Ian Schreiber (co-author of Challenges for Game Designers) gave his version of kinds of fun (enjoyment):

exploration

social experience

collection (collecting things)

physical sensation

puzzle solving

advancement

competition

Ask a group of game players to list ways that people enjoy games, and many of the above will come up in one form or another.

Raph Koster (in A Theory of Fun for Game Design) has brought to our attention research by Mihaly Csikszentmikalyi into “optimal experience.” The Chicago-based Czech researcher applies his ideas to life as a whole, in a series of books, but we can apply them to games. Csikszentmikalyi is interested in “the positive aspects of human experience — joy, creativity, the process of total involvement with life I call flow” [Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (1990), p. xi].

For game purposes it amounts to this: People have an optimal experience when they are challenged, but not challenged too much. In other words, if something is too easy, it becomes boring. If it’s too hard, it becomes frustrating and causes anxiety. The ideal game experience, then, is to challenge the player at whatever ability level he has reached, that is, keep increasing the challenges as the player becomes a better player. This keeps players “in the flow” (see the diagram).

Video games can be particularly good at managing the level of challenge, either through adaptive programming, via the difficulty setting, or through increasingly difficult levels in games that use levels. In non-electronic games, the level of challenge tends to change because your opponents tend to become better players just as you do, or you find better players to play against. In a non-electronic role-playing game such as Dungeons & Dragons, the referee (Dungeon Master) manages the challenge. Novice characters don’t meet fire giants but often encounter orcs, while very powerful characters may occasionally go up against an ancient and terrible dragon, but orcs aren’t worth bothering with. This is in some sense artificial, but it makes the game more enjoyable.

Enjoyable to Some, Yet Not to Others

While these schemes and categories are all useful ways to think about games, I think game enjoyment often involves spectra of factors, with some people at one end, others at the other end, and the majority somewhere in the middle. Many of these spectra overlap, or are different views of what may be a more fundamental factor.

Here’s a list of some of the factors (certainly not definitive) that I’ll discuss:

role-fulfillment vs. emergence (story dominant vs. rules dominant)

story/narrative vs. what happens next/emerging circumstances

classical vs. romantic

long-term planning vs. reaction/adaptation to changing circumstances

socializing vs. competition

entertainment vs. challenge

fantasy/relaxation vs. urge to excel (“gaming mastery”)

the journey vs. the destination.

Role-Fulfillment vs. Emergence (Story Dominant vs. Rules Dominant)

Many people have suggested that video games are dream fulfillment: What is the player’s dream that the game designer wants to help them experience or fulfill? Yet in many games the dream, if it is there at all, is quite obscure. What is the dream fulfillment in playing chess or checkers, or any other abstract game, such as Tetris? Is there anything personal (other than a desire for immortality?) in controlling a nation for a thousand years, as in History of the World, Age of Empires, or Civilization?

Certainly many video games put the player into a position the individual is unlikely to experience in the real world, or which they wouldn’t want to experience because it’s much too dangerous. Living out fantasy is an obvious part of shooters and action games, for example.

This kind of game can also be called “story-dominant.” If there’s a dream to be fulfilled, it likely involves a story, and the game is an expression of that story, however simple (just as dreams can be simple or complex).

The other end of this spectrum is the “rules-dominant” game, which includes many traditional games such as chess and go. Gameplay emerges out of the rules, not from following a story (hence, it is sometimes called “emergent” gaming). The game has a set of rules, and the course of the game emerges from the rules in a great variety of ways, depending on the players. Board games and card games tend to be rules-dominant, while many of popular video game genres — and role-playing games of all types — tend to be more story-dominant.

We might further say that the rules-dominant games are often for more than two sides, whereas the role-dominant ones tend to have just two sides, the player(s) and the computer (or referee, in Dungeons & Dragons and similar games).

Video games, especially the AAA variety, are much more exercises in role-assumption than non-electronic games. The player is enabled to do something he’d like to imagine he could do, but he can feel as if he’s really doing it in modern AAA games. The feeling of verisimilitude must be there. On the other hand, “casual” video games tend to be more rules-dominant, like board games and card games.

Sid Meier recently described what amounts to an “emergent” view of games:

“It’s important that the player has the fun in the game,” [Meier] said, noting that there is a temptation for the designer to steer the gameplay too much. “It’s definitely our philosophy to keep the game designer in the background and let the story emerge from players’ decisions.” (Chris Faylor, Shack News, February 20, 2008.)

The next question discusses other aspects of these two contrasting approaches.

Story vs. Emerging Circumstances

Some game players like to follow a story, while others hate to be led around by the nose. Yet they’re talking about the same experience. This is usually expressed in the contrast of “linear” games with “sandbox” games.

It is much easier to produce a powerful story through linearity (as in a book or movie), so the strongest (in terms of story, at any rate) of the story-dominant games are linear.

Sandbox games have greater replay value than linear games (other things being equal) because there is only one or a few stories in the latter. Of course, if the linear game is very long, will people miss a lack of replayability?

Sandbox video games such as Grand Theft Auto and Assassin’s Creed are a return to the older video game style, where specific narrative (linearity) is less important or non-existent.

The role-assumption game isn’t necessarily strongly linear or story-dominant. The ancestor of many video games, Dungeons & Dragons (paper version), can be played either way. The dungeon master can conceive a story and set up an adventure so that players are forced to follow through the story (linear method). Or he can set up an appropriately challenging situation, not trying to predict how the players will approach it and not trying to lead them from a particular point to another, and see what happens (sandbox method). In this case the players make their own story. And each group confronted with the same adventure will contrive a different story. It’s easier to do the sandbox in a paper game than in a video game, because a good human referee is more capable than a computer of adjusting the game as it is played.

I always hated storytelling D&D as a player, because it meant the referee forced me to do things I didn’t want to do. But other people much prefer the story-driven style. Of course, there is story in the emergent style, and there is strategy and tactics in the story style. I’m talking about what’s dominant.

What seems to be certain, however, is that many players lean strongly to one side or the other, and don’t like games of the other type most of the time.

Classical vs. Romantic

Two basic game playing styles exist among those who are interested in winning a game (not all players are, of course). Harkening back to the well-known 19th century distinction in music, painting, and other arts, I call the two basic styles the classical and the romantic.

The perfect classical player tries to know each game inside-out. He wants to learn the best counter to every move an opponent (or the computer) might make. He takes nothing for granted, paying attention to details that probably won’t matter but which in certain cases could be important. The classical player does not avoid taking chances, but carefully calculates the consequences of his risks. He dislikes unnecessary risks. He prefers a slow but steady certain win to a quick but only probable win. He tries not to be overcautious, however, for fear of becoming predictable. He tries to maximize his minimum gain each turn — as the perfect player of mathematical game theory is expected to do — rather than make moves and attacks that could gain a lot but which might leave him worse off than when he started.

Some people call this the “minimax” style of play. I am not sure that “minimaxer” and “classical” mean quite the same thing in game contexts, but they are close. Certainly, the minimaxers are usually going to be classical types.

A cliché among football fans is that the best teams win by making fewer mistakes, letting the other team beat itself. So it is with the classical gamer, who concentrates on eliminating errors rather than discovering brilliant coups.

The romantic, on the other hand, looks for the decisive blow that will cripple his enemy, psychologically if not physically on the playing field. He wishes to convince his opponent of the inevitability of defeat; in some cases a player with a still tenable position will resign the game to his romantic opponent when he has been beaten psychologically. The romantic is willing to take a risk in order to disrupt enemy plans and throw the game into a line of play his opponent is unfamiliar with. He looks for opportunities for a big gain, rather than maximizing his minimum gain. He loves the brilliant coup, despite the risks.

Chess lends itself to classical play, poker to romantic play. But each one can be played with the opposite style.

Because so many video games let you save your position and experiment with different strategies, the romantic style may be more common among video gamers.

Long-Term Planning vs. Adapting to Changing Circumstances

Some people like to plan well ahead, to consider the options and choose a best course for each. Others like to react to circumstances as they occur, to adapt. Chess and checkers encourage long-term planning. Monopoly, thanks to the random move mechanic and more than two players, is more adaptive. Having more than two players introduces additional uncertainty to any game; uncertainty is at the heart of the adaptive style. Poker involves adaptation in each hand, but in the long run, the best players may be able to plan their bluffs (and non-bluffs) so as to take advantage of the characteristics and personalities of the other players. Card driven war games put an emphasis on adaptation: you can only do what your current hand allows you to do, you never know what cards you’ll get, and you don’t know what cards your opponent holds.

In general, perfect information games encourage planning, while as uncertainty increases, adaptation becomes more important than planning. For a variety of reasons, adaptation is probably the more common preference among video gamers.

Socializing vs. Competition

Party gamers are the epitome of the socializers. Many Euro-style board gamers and casual video gamers are of this type, to the point that they refuse to attack someone even when playing in a competitive game. They play games to enjoy being with and interacting with other people of similar interest, and have little interest in dominating or beating someone. I don’t think we need to discuss the competitive gamer much. We all know people whose main gaming objective is to win, to outdo everyone else.

The availability of a social experience is important. Non-electronic board games and card games are generally social experiences; electronic games are becoming more social (MMOs, Wii), but are still predominantly solitary, a player alone with his own thoughts and dreams.

Non-electronic RPGs are often social, as the games are usually cooperative rather than competitive.

Entertainment vs. Challenge

Traditional thinking about games sees them as competitions or challenges, where players play against one another. Dungeons & Dragons changed that, as players played against “the bad guys” with the Dungeon Master as neutral referee. It is a cooperative game, though there is still an unending series of challenges.

Some video games have gone further by leaving competition entirely out of it and reducing challenges. Games have become entertainments, not competitions. (Of course, many family games were played as entertainments even though they were ostensibly competitions.) Many people pay their 60 bucks (or 20 bucks, or 5 bucks) and want to be entertained, not challenged. Yet there are still competitive players and highly competitive games. Spore is reportedly “too easy” for hardcore players, yet challenging enough for the much larger market of more casual players. Evidently it is an entertainment rather than a challenging, competitive game.

In a sense, any game can be played as an entertainment or as a competition, but design will make some much more suitable as one than the other. Insofar as people often “don’t want to think” when playing games, many video games substitute “physical challenges” (such as jumping in platformers, or shooting accurately) for mental challenges. The physical challenges can easily be modified to entertain or to challenge, as the player wishes.

Playing against people online tends to be challenging. Playing against people in person tends to be entertainment, perhaps because we’re more likely to know the other people involved.

Some writers on this topic speculate that socializing and entertainment tend to be more important to female players, whereas challenge and competition are more important to males.

Relaxation vs. Mastery

A variation of the above is to play a game as fantasy fulfillment, or to play the game to fulfill the urge to excel, to demonstrate gaming mastery. The latter helps the player feel important, capable, powerful, hence its great attraction to teenagers. A game can often provide both, if only through different difficulty levels.

Unfortunately, the urge for gaming mastery, when taken to extremes, results in players willing to cheat or behave in unsocial ways that can ruin everyone else’s enjoyment.

Some people just don’t see the point of excelling in a video game. What does it matter? A player’s attitude can change over time, likely moving more toward relaxation as the player becomes older and encounters more real-world challenges and responsibilities. Mastering a game simply becomes less important.

The Journey vs. The Destination

Older generations want to enjoy the entire game they are playing, even when their main objective is to win. Young people seem to be more interested in the destination, “beating the game,” than in the journey. Obviously, it’s necessary that a game have a sufficient level of challenge that the “destination” player feels he’s accomplished something.

This can also be seen as “what happens” versus “what is the end.” Some people play games (and read novels, and watch movies) to find out what happens next. Others are only interested in the final result. They might skip ahead in a novel and just read the end, or skip ahead in a game (often with “cheats”) and just play the end.

I once listened to a young man who had written two books about generational differences say that his generation (gen Y or millennials) were quite happy to get a cheat code, go to the last stage of a game, “win” the game, and be satisfied. “I beat the game, didn’t I?” I, a baby boomer, was astounded. “Why play if you’re going to cheat?” He smiled as he said, “We’re just gathering the fruits of our research.” I shook my head. To this day I cannot understand this emotionally, but I understand intellectually that many game players feel this way — that the destination is all that matters. And a game designer must be aware of it.

The following is another observation of this phenomenon:

“The fact that there’s no ending [100 levels repeat randomly], however, points out a very important difference between Atari’s view on video games and the current perception. Atari saw Gauntlet as a process, a game that was played for its own sake and not to reach completion. The adventurers continue forever until their life drains out, their quest ultimately hopeless.

… in games of Gauntlet I’ve had with other people in the past few years … their interest tends to survive only until the point where they learn there is no ending. Times have certainly changed.” (John Harris, “Game Design Essentials: 20 Atari Games,” Gamasutra.com, May 30, 2008.)

I’d speculate from my experience with game design students that, for whatever reasons, females tend to be more interested in the journey, males more interested in the destination.

We might speculate also that MMOs with level caps (which is typical because it’s hard to design a MMO without a level cap) suit the destination folks, because there is a destination: that maximum level. Similarly, RPGs such as Final Fantasy are attractive to destination people because there is an end to the story. In older RPGs, both the original non-electronic ones and some of the older video games, the game is open-ended. There is no particular destination.

I find it instructive that the latest version of non-electronic Dungeons & Dragons (fourth edition, June 2008) has a definite end. Characters retire, one way or another, when they reach 30th level, and that level is practically reachable, as opposed to a tightly run first edition game where no human character ever got to a maximum level (and certainly not 30th!).

I’ll end with a couple of additional observations.

Escapism?

Dream-fulfillment is close to escapism. Like it or not, many games have a strong escapist element, and it seems strongest where dream-fulfillment is strongest. It is especially important to non-adults. Consider, say, a favorite adolescent male pastime, shooter games:

The player can be the star, “da man,” which is generally unlike the player’s real life

Players can experience thrills (even death) without risk of being hurt

There’s always a way to succeed — trial and error can work, because it doesn’t matter if you get killed

Competition is not only permissible, but encouraged

There’s a structure to everything; most of the uncertainty of real life is not there

Young people control what happens, and attitudes can be confrontational, edgy.

For a frustrated teenage male who’s been told too often what he can and cannot do, this can be a kind of nirvana. Game designers must be aware of the escapist elements of gaming, even if they’re designing a serious game that has few or none of these particular characteristics.

Personalities

Game players have different kinds of personalities, just as the population at large. A fairly common taxonomy divides people into 16 personalities, as reflected in the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and in the writing of David Keirsey and others (for example, the book Please Understand Me). These are often derived from the work of Carl Jung, and even back to the Greek idea of the “four temperaments”. (There is a practical Jung Typology test of personality type online.)

The major point to recognize is that different personalities have different preferences, different ways of collecting information, different ways of reacting to challenges. These personalities are established in childhood and do not change. For example, some people feel better before they make a decision than after, so they tend to gather more information and delay decision-making. Others feel better after they’ve made a decision, so they react to decision-making quite differently. The former may learn to make timely decisions, but to a considerable extent it is against their nature. Similarly, some people rely heavily on logic, others on intuition. Such differences are going to strongly affect their tastes in games, or even whether they play games at all. Keirsey suggested that certain occupations tend to attract certain personality types, and we can wonder if game playing attracts only some of the 16 types.

The major point for inexperienced designers to take from this is you are not like your audience, and you need to decide which kinds of preferences and which ideas about enjoyment your games will target. No game can begin to cover all the bases because there are so many different reasons to like to play games.(source:gamecareerguide)

上一篇:设计师需警惕霸权商品破坏游戏体验

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号