探讨2D平台游戏的基本元素及跳跃艺术(上)

作者:Joris Dormans

引言

《大金刚》的诞生标志着宫本茂开创了一个新的电脑游戏类型——平台游戏。玩家在2D游戏世界里上蹦下跳,同时还要躲避各种陷阱和摇摆物,这成为整个八十年代至九十年代初成功游戏的开发基础。随着3D游戏,特别是第一人称射击游戏的崛起,经典的平台游戏逐渐丧失其优势。而现在,玩家们与时俱进,平台游戏鲜有新作问世。(请点击此处阅读本文下部分内容)

平台游戏以不同的方式继续存活着。许多2D平台游戏在主机、平板和智能手机上找到了繁荣滋长的土壤。然而,这种状况能维持多久,只能让时间来让证明了。即使游戏制作的技术正在飞速发展,但我怀疑大多数平台游戏的3D化进程仍然是长路漫漫。另外,当前还存在一些复古游戏和怀旧的玩家。正是这类玩家在维持平台游戏的生命力。某些游戏杂志和专家等认为复古游戏已经成为一个趋势。于是,经典的平台游戏又在众多老游戏中被重新挖掘。老粉丝们为了满足自己对新原创游戏的欲望,仍然在开发平台游戏。免费但非常困难的《Eternal Daughter》就是一例。终于,平台游戏的典型动作和玩法借助某些系列游戏(游戏邦注:例如《超级马里奥》、《波斯王子》的3D化和新作开发(《古墓丽影》),得以留存下来。

在本文中,我将探讨2D平台游戏在其巅峰时期的魅力所在,即典型平台游戏的关键和基本元素是什么?我个人认为问题的答案应该从平台游戏的独特玩法中寻找。正是动作和限时的动觉感观乐趣吸引着玩家不断地游戏,特别是当这种乐趣与关卡的设计和基于典型的探索的剧情紧密结合时。

游戏玩法

在我们开始分析平台游戏之前,我们必须明确游戏玩法这个复杂的概念。大多数玩家都可以证明玩法是任何游戏的决定性元素。一款游戏即使在音效和画面都非常棒,但如果玩法上不过关,那么它还是很难受到玩家的欢迎。不过,什么是游戏玩法所必需的,则更难以确定。

在《Rules of Play》一书中,Katie Salen 和Eric Zimmerman将游戏玩法定义为“是一种形式化的交互作用,产生前提是玩家遵守游戏规则,且在游戏中体验系统。”这个定义包含了三个重要方面:1)玩法是介于玩家与游戏之间的交互作用;2)它是形式化的,且遵循游戏规则;3)它是通过游戏而获得的体验。大多数关于游戏和游戏玩法的解释都认可它是一种交互作用。事实上,交互作用常常被认为是游戏的定义之一。方面2)大概不那么显著,但自Johan Huizinga(游戏邦注:Johan Huizinga是荷兰的历史和文化学家)在其著作《游戏的人》(Homo Ludens)中讨论游戏在文化和社会中的重要作用,它就变得重要了。一方面,它与“游戏性态度”,即玩家自愿服从约束其完成游戏的方法的一系列规则;另一方面,它暗含其是一种可设计的东西。最后,游戏玩法是游戏的主观体验。这大概是“游戏玩法”这一术语令人迷惑不解的原因,因为玩家的品味和技术各不相同,要为他们设计主观的游戏体验是很困难的。

游戏玩法不仅是一种主观体验,还受到品质的影响。一定程度上,所有游戏都有游戏玩法,但并非所有游戏都有良好的游戏玩法。优秀的游戏玩法常常能在游戏中的众多元素中取得微妙平衡。在《the Art of Computer Game 》一书中,游戏设计师Chris Crawford将游戏玩法、游戏的节奏和学会玩该游戏所需要的认知努力联系在一起。快节奏的游戏应该减少认知投入精力,而慢节奏的游戏可以要求玩家付出更多的认知投入精力。在这两方面实现平衡的游戏可以说具备了良好的游戏玩法。Doug Church在某篇文章中强调了控制和连贯的重要性。他以《超级马里奥64》为例阐明了这一观点。在游戏中,设计师“给予非常有限的动作”但又完全满足游戏需要,从而使玩家获得控制感。

控制方式是区别日本游戏设计和欧美游戏设计的一个重要方面。这一观点贯穿Kohler的《Power Up》全书,也被许多游戏设计师所强调。宫本茂如此解释:“如果游戏操控方式没有乐趣,那么画面、音效、甚至角色和剧情都是毫无意义的。”日本和欧美游戏的设计差别在很大程度上是由早期日本和欧美游戏所欣赏的文化背景造成的。欧美游戏行业吸引的是工程师、电脑专家和商人,而日本游戏设计师往往具有美术方面的背景。宫体茂持有工业设计学位,抱着设计玩具的想法供职于任天堂。在他进入游戏设计领域之前,他曾参与一些公司的初期电子游戏设计项目。当他着手《大金刚》之时,他还没有真正的设计经验。

日本设计师对游戏设计观念与欧美同行们是不同的,相比之下,他们更关注玩家和游戏之间的交互作用,这种敏锐的洞察力与欧美设计师偏重游戏设计技术是大大相反的。日本出身的设计师Dylan Cuthbert将其总结为:“我们想要高超的技术,但我们更关注游戏的品质。我们希望玩家玩得开心,不是为我们或者设计师,而是为他们能努力实现设计技巧得到快乐。”日本游戏的成功在于围绕一个小的想法或动作来设计游戏,如《口袋妖怪》的设计师田尻智解释道:《吃豆人》是围绕“吃”这个动作设计的,而《口袋妖怪》则是“驯服”。与此类似,马里奥当然是“跳”。

显然,设计早期的平台游戏的玩法需要付出大量努力。但是,单凭这种努力并不能解释这类游戏的成功。为了搞清这点,我们必须理解由运动、定时和探索这三者之间的特殊平衡所组成的游戏玩法。我们还必须回答这个问题——为什么跳起来踩死敌人就那么好玩?

像马里奥一样思考

你抓着控制器,精力一恢复,你就完成了新关卡的初期阶段。敌人很快就登场了,你轻松到达门口。在拱廊这,你折腾了好一阵子。打倒第一关的BOSS已经够了难了,结果这里上蹿下跳的飞头来得还这么多这么快。没有时间琢磨它们的运动路径,更别说打中它们了。你冲过去,左躲右闪,想跳过它们。没用,你一次又一次地撞上这又快又难躲的东西。但之后你发现走道有一个点是安全的。此时你的体力所剩无几,你终于明白,如果你从一根柱子跳到另一根柱子,就能避开它们的路径了。恍然大悟之后,你突然就很轻松地闯到楼梯处了。你登上台阶,却发现更多飞头在等着你,它们的飞行路径跟刚才的又不一样了,你却来不及分析了。

以上说的正是《恶魔城》的简要游戏过程(图1)。由此我们可以看到平台游戏吸引人的地方。首先,玩平台游戏是一个化身感很强的过程。许多游戏的本质就是沉浸感和代入感,当它用于屏幕上的角色或投射到游戏世界中,就成了吸引玩家的临场感。也就是,玩家不只是在玩游戏,还获得一种亲临其境的感觉,在游戏世界里,你占据了虚拟空间的一个主体。这个效果在现代3D游戏中表现得最为显著,因为玩家能看到的角身所处的游戏世界。玩家所处的空间与角色一致。不过,在所谓的第三人称平台游戏中,玩家可以在屏幕上看到角色,那种感觉就要弱一些了。为了完成这些游戏,我们必须指挥我们的角色避开各种陷阱、通过重重关卡。玩家对角色的认同感一般相当强烈。

并非所有的游戏都能带来这种强烈的化身感。Friedman这样描述玩家与策略和模拟游戏的交互作用:玩家必须同时与整个系统产生直接的交互作用。这种交互作用是无实体的,玩家能直接感知游戏所提供的信息,几乎好像那本来就是玩家大脑或身体的控制延伸。“像电脑一样学习思考”是Friedman形容游戏的超验感,即抛开本体,达到一种对游戏模拟和深层结构的控制意识。

平台游戏的化身并不一定意味着人本身的表现。事实上,这种情况极少发生。马里奥拥有超人的能力和精力,可以在平台上跳来跳去。他最喜欢的杀敌方式就是跳到敌人头上,但这跟真实的人类生理机能没有什么关系。学会这样控制身体相当于在战略游戏的虚无感中与“其他东西”接触,但这种虚无感的乐趣来自其要求玩家具备的超验感,而实体体验的乐趣则是运动感官性的。正是乐趣和控制感和成就感,再加上一系列执行良好的动作,使得玩平台游戏变得趣味无穷。跳死乌龟和甲虫之所以有趣,是因为这个杀敌方式需要玩家通过计算机空间来充分发挥受控身体的优势。

然而,平台游戏并非带来纯粹的化身体验。优秀的平台游戏的关卡同时也给玩家出谜题,角色及其活动是解答的关键。就我们所知道的角色,玩家的外在观点常常有助于设计和分析游戏中的关卡。以《恶魔城》为例,安全地点恰好与走道上的柱子一致的情况并非巧合。为玩家提供躲避飞头难题的线索是有设计意图的。平台游戏广泛运用这种类型的暗示和线索。学会识别关卡中的符号系统,对于通关成功是非常重要的。学会“像马里奥一样思考”就是是掌握游戏世界的自然法则,掌控角色以及理解此二者如何产生交互作用。

流程

Victor Nicollet详细说明了玩家在平台关卡中遭遇的不同类型的障碍。即:

陷阱:这是指需要玩家用技术和操作来避开的地形特征。最简单的例子就是,两个平台之间的空隙。陷阱不会发生变化,只需要一点点操作就能通过。

摇摆物:这类障碍需要捏准一定的时间间隔才能安全通过。其实就是在陷阱的基础上增加了时限因素。

不稳定地面:这类障碍的安全只能维持一小段时间,这迫使玩家必须快速通过。

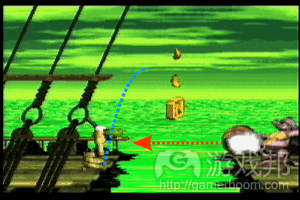

以上三类可以组合成复杂的关卡模式和难度渐增的障碍。图2-6所示游戏过程选自《Donkey Konk Country 2》中的“Rattle Battle”关卡。从中可见这种模式集合了这三类障碍的所有元素。角色(左边的蛇)必须在固定的间隔时间内避开射向它的木桶(摇摆物,图2和图3),并且跳上一个马上就会被破坏掉的木桶(不稳定地面,图5)才能跃过间隙(陷阱,图4-6),最后跳上正朝着角色发射木桶的鳄鱼(可以看作是陷阱,图6)。

要通过这些障碍需要一定的练习,但是,一旦玩家发现只需要跳上木桶就能跃过间隙,算好最佳起跳时间,那么这一系列动作也就相对容易完成了。这是出现在相同关卡中的三个难题中的第一个。第二个难题要求玩家躲开大炮球(不能当作跳板),然后跳上一只飞舞在间隙上方的蜜蜂(图7)。技巧就是从一个玩家看不到火球但听得到发射声音的固定点开始连续的跳跃动作,开始跳向障碍的同时,新的发射也在进行(图8)。最后一个障碍要求玩家执行一个高技巧的跳跃动作,即跳过木桶后马上又跳起来击败鳄鱼(图9和图10)。注意最佳的起跳点是以背景上的几个木桶作标记的,而玩家必须击中木桶的地方是用香蕉所在方位作标记的。

Nicolette并没有在文中讨论敌方角色。许多敌人的行动就相当于陷阱、摇摆物、不稳定地面或这三者的组合。图7中的蜜蜂所起的作用就是不稳定地面。鳄鱼枪手制造摇摆物的同时也起到陷阱的作用。有些敌人要求玩家执行更复杂的动作,如前进、跳过鳄鱼(图11)。玩家如果能跳到鳄鱼头上就能消灭它们,否则就是反被消灭。因此,鳄鱼就相当于摇摆物:当它们在高空时就是危险的,当它们接近地面时就可以被击败或避开。因为它们也朝玩家移动,玩家没有时间想出击败它们的正确节奏。

游戏邦注:原文发表于2005年11月,所涉事件及数据均以当时为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Art of Jumpin

Joris Dormans, November 2005

Introduction

When Shigeru Miyamoto designed Donkey Kong he invented a new genre of computer games. The platform game where the player jumps around a two dimensional game world, dodging various pits and pendulums, became a recipe one which many successful games were based throughout the eighties and early nineties. With the rise of 3D games in general and the first person shooter genre in particular, the classic platform game has lost its edge. Gamers have moved on, and the release of new platform games is a rare occasion, these days.

Still, the genre lives on in many ways. A lot of games on mobile consoles, PDAs and smart phones are still 2D, and the platform genre thrives on these gadgets. However, how long this is to be remains to be seen. The technology of is making giant strides forward and I doubt it will take long before most of these games have also moved to 3D. Next, there are the retro-games and retro-gamers, who keep the genre alive. Retro-gaming has become a trend that is recognised by gaming magazines and scholars alike. The classic platform games are one of many game genres that are being rediscovered. Old school fans still produce platform games in order satisfy their appetite for new and original titles. The freely available (and fiendishly difficult) game Eternal Daughter is an example of this. Finally the typical action and gameplay of platform games lives on as some series have made a successful move into the 3D area (Super Mario, Prince of Persia) and has spawn new series (Tomb Raider).

In this article I will investigate the popular appeal of the 2D platform game during the genre’s heyday. What are critical and essential elements of the typical platform game? It is my view that the answer must be looked for in the particular blend of platform gameplay. I think the kinaesthetic pleasure of movement and timing is what enthrals the player to keep on playing and keep on coming back, especially when this is tied in closely with the design of the levels and a form of storytelling that builds on the arch-typical quest.

Gameplay

Before we can proceed to analyse platform games we need to define the ever elusive notion of gameplay. As most gamers will testify gameplay is a crucial element of any game. A game can look and sound fantastic, with out half-decent gameplay, it will still be poorly received. Yet, what this gameplay entails is more difficult to pin down.

In Rules of Play Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman define gameplay as “the formalized interaction that occurs when players follow the rules of a game and experience its system through play” (2004: 303). Three elements in this definition are essential: 1) gameplay is an interaction between player and game, 2) it is formalised and follows rules, and 3) it is an experience through play. Most accounts of games and gameplay acknowledge the interaction (1); in fact interaction is often postulated as one of the defining aspects of games. The fact that this interaction is formalised and follows rules (2) is perhaps less obvious, but has been on the map since the writings of Johan Huizinga. It is on the one hand related to the “lusory attitude”, the gamer’s voluntary submission to a set of rules that effectively limit her means for reaching an end (ibid. 97) and, on the other hand, implies that it something that can be designed. Finally, gameplay is the subjective experience of play. This is what probably makes the term so illusive, for it is hard to design this subjective experience for players whose tastes and skills vary.

Gameplay is not only a subjective experience, it is also subjected to strong sentiments about quality. To a certain extend, all games have gameplay, but not all games have good gameplay. Good gameplay is often a subtle balance to many factors in a game. In The Art of Computer Game Design Chris Crawford associates gameplay with game’s pace and the cognitive effort required by playing. A fast-paced game should not require to much cognitive effort, while a slow-paced game can ask more difficult decisions of the player. Games that strike a good balance between these two are said to contain good gameplay (1983: 21-22). In a Gamasutra article Doug Church (1999) stresses the importance of control and coherence. He illustrates this with a discussion of Super Mario 64 in which the player is given a sense of control by “offering a very limited set of actions, but supporting them completely”.

Control is also one of the magic ingredients that sets Japanese game design apart from Western game design in Power Up (Kohler, 2005). It is a point that returns throughout the book and is stressed by many game designers. Miyamoto is paraphrased to say: “Graphics, music, even characters and story mean little, if play control isn’t interesting and fun” (Kohler 2005: 273). The difference in Japanese and Western design philosophies is largely attributed to the difference in cultural status that early games enjoyed in Japan and the West. While the Western game business attracted engineers, computer scientist and businessmen, the Japanese designers often had artistic backgrounds. Miyamoto holds a degree in Industrial Design and came to Nintendo with the idea of designing toys. Before he started designing games he had worked on the case design of some of the companies earlier electronic games. When he started working on Donkey Kong he had no real programming experience (ibid: 26-35).

Japanese designers brought a different mentality to game design than their Western counterparts, a lot of attention was paid to the interaction of the user with the game. This eye for detail is in stark contrast with the Western pre-occupation with the technical side of designing games. Japanese based designer Dylan Cuthbert sums it up: “We want the good technology, but we really want the game to be quality. We want the player to be happy, not for us, the designers, to be amused by pulling off programming tricks” (quoted in ibid. 180). The Japanese successes are focused games that were designed around a simple idea, or verb as Pokémon’s designer Satoshi Tajiri explains: Pac-man is designed around the verb ‘to eat’ and Pokémon around the verb to trade (ibid: 240). Likewise, Mario games are, of course, designed around the verb to jump.

Clearly, a large effort was made while designing the gameplay of those early platform games. But this effort alone does not explain the success of the genre. To understand that we need to understand the peculiar balance of movement, timing and exploration that makes up the gameplay. We need to answer the question why it is fun to defeat you enemies by jumping on them?

Figure 1 Dodging flying heads in Castlevania

Thinking like Mario

You grasp the controller with renewed vigour as the as you make your way through the initial stages of the new level. The opponents are quickly disposed and you reach the door with ease. Now comes the arched hallway that has eluded you for a while. Getting past the first level’s boss is already hard enough, but these flying heads that dance up and down in sinus patterns are to fast, and too many. There is little time to anticipate their trajectories and let alone to try and hit them with you whip. You rush in, dodging left and right, occasionally trying to jump over them. To no avail, you are hit time and time again by the fast and elusive critters. But then you find a spot in the hallway where your save. With only a few hitpoints left it dawns upon you, if you hop from column to column you stay out of their trajectories, and all of the sudden getting past this part is easy. You make it to the stair and rush up the steps, only to discover more flying heads that run in new patterns which you fail to analyse in the few seconds that you last.

The previous paragraph illustrates a brief sequence of gameplay experience with the game Castlevania (see also figure 1). It illustrates some aspects of platform gameplay that contributes to the genres appeal. First of all playing a platform game is a strong embodied experience. A sense of immersion and agency is the providence of many games, when this is directed at an avatar on the screen or projected in the game world it is a sense of tele-presence that enthrals the player. You are not just playing a game, you get a sense of being there, in the game world, a sense that you occupy a body in the virtual realm. This effect is most prominent in modern 3D games that present the game world as your avatar can see it. The player occupies the same space as its avatar. In platform games and so called third-person games where the avatar is visible on the screen the feeling is only slightly less. In order play these games we need to direct our avatar past various traps and trough a multitude of levels. The player’s identification with the avatar is usually quite strong.

Not all games offer such a strong sense of embodiment. Friedman (2002) describes how players interact with strategy and simulation games where the player needs to interact directly with a whole system at a time. This interaction is disembodied, all the information provided by the game feeding directly into her awareness, almost as if they were direct cybernetic extensions of her body or brain. “To learn to think like a computer” is the way Friedman describes the transcendental feeling these games of leaving ones body behind and achieving a cybernetic awareness of the game’s simulation and its underlying system.

figure 2 Donkey Kong Country 2

figure 3 Jump over the barrel…

figure 4 …on to the edge…

figure 5 …on the slow barrel…

figure 6 …and onto the crocodile!

figure 7 A similar sequence…

figure 8 …that starts with an auditory cue

figure 9 The final sequence…

figure 10 …and final victory of the level

figure 11 Jumping and advancing crocodiles

figure 12 Facing the vizier in Prince of Persia

figure 13 Abe and two sligs in Oddworld

The embodiment of platform games does not necessarily mean human embodiment. In fact, it rarely does. Mario possesses a super-human ability and stamina to jump around platforms. His favourite way to dispose of his enemies by jumping on their heads has little to do with real life physiology. Learning to control a body like this is as much an interface to ‘something other’ as the disembodied trance of strategy games, but where the pleasure of disembodied experience comes from the hyper awareness it requires from the player, the pleasure of the embodied experience is kinaesthetic. It is the fun and feeling of control and achievement that accompanies a series of well-executed moves that makes playing a platform game pleasurable. Jumping on turtles and beetles is a fun way of disposing of ones enemies because it requires us to make the most of our excellence in moving our cybernetic body through the computer space.

However, platform games do not deliver a purely embodied experience. The levels of a well designed platform game are at the same time spatial puzzles for which the avatar and its movement is the key. As much as we identify with the avatar, the player’s external perspective is often instrumental in designing and resolving levels of the game. In the Castlevania example it is no coincidence that the save spots coincide with the columns in hallway. It is designed that way to provide the players with a clue to solve the particular problem of dodging the flying heads. Platform games make extensive use of this type hints and clues. Learning to recognise the system of signs in a level is vital in conquering the level. Learning to ‘think like Mario’ is to master the physical laws that govern the game, to master the control of the avatar, and to understand how these interact.

Flow

Victor Nicollet (2004) details different type of obstacles that players encounter in platform levels. These are:

Pits are those terrain features that require skill and control to avoid. In their most simple form these are the gaps between the platforms the player must avoid. Pits do not change and require a little control to navigate.

Pendulums are obstacles that can only be safely navigated at regular intervals; these add a factor of timing to the control required by the pit.

Unstable floors, are obstacles that are save for only a short while, putting pressure on the player to get past the obstacles quickly.

These elements are combined in complex patterns to form levels and obstacles of increasing difficulty. The sequence of play detailed in figures 2-6 details such a pattern that combines all elements of all three types. It is a sequence taken from the ‘Rattle Battle’ level of Donkey Konk Country 2. The avatar (the snake on the left) needs to avoid barrels shot at her at regular intervals (pendulums, figures 2 & 3), and jump over a gap (pit, visible in pictures 4-6) by jumping on a barrel which is immediately destroyed (unstable floor, figure 5) and finally jumping on the crocodile that fires the barrels to destroy him (who can be considered to function as a pit, figures 6).

To get past this obstacle requires some practice but once the player discovers that she needs to jump on the barrel to cross the gap, and when she has figured out the best timing to do this, it becomes relative easy and satisfying to execute the moves (“take that you crazy crocodile!”). This is the first puzzle of a series of three that occur in the same level. In the second puzzle the player needs to dodge cannon balls (which cannot be used as a jumping platform) and jump on a bee that hovers over the gap (figure 7). The trick is to initiate the series of jumps from a fixed point where the player cannot see the actual fire balls but can hear them being fired, and start jumping towards the obstacles at the same time a new shot is fired (figure 8). The last obstacle requires the player to perform a tricky high jump unto a barrel and immediately jump onwards from their to defeat the crocodile (figures 9 and 10). Notice that the best spot to start the jump is marked by some barrels in the background while the place where the player needs to hit the barrel is marked by the position of the bananas.

Nicolette does not discuss enemy characters in his article. Many enemies behave just like a pit, pendulum, unstable floor or a combination there of. The bee in figure 7 functions as an unstable floor. The crocodile gunner is the source of a pendulum and functions as a pit. Some enemies introduce more complex behaviour, such as the advancing, jumping crocodiles (figure 11). These are defeated by jumping on them, but they will kill the player if they land on them. In this way they act as pendulums: they are dangerous when they are high in the air, but can be defeated or avoided when they are close by the ground. Because they also advance on the player, she has little time to get the correct rhythm required to defeat it. (source:jorisdormans)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号