详述电子游戏关卡设计之20点原则及建议(3)

作者: Tim Ryan

11)凸显独特性

说得容易做得难,今天独特的游戏元素非常罕见。但至少在关卡设计领域,你还是可以用新方式结合不同元素,讲述不同故事。另外要记住,没有哪一款优秀游戏能够完全与前辈或竞争者脱节,而你也不例外。有时候你可以通过调整他人的关卡设计,从而突出你认为其缺乏的元素,或者体现你的关卡更胜一筹。你常会有一些新想法添加到自己的设计素材中。你可能会发现自己的关卡设计是前所未有的想法,或者从他人那里得到灵感而进行创新尝试。关卡独特性并不需要完全取决于原创性,你的个人喜好会体现在自己的设计中,而这一点就已足够显示其独特性。无论你如何落实想法,独特性都可以令你的关卡与游戏区别与其他作品。

12)不要指望玩家阅读文本内容

不要寄希望于所有玩家都会阅读对话或任务描述,也不要太相信他们的观察、预知能力或者逻辑推理能力。玩家只有亲眼看到才会知道发生什么状况。俗话说“一图道千言”,这话用于关卡设计再合适不过了。在一定程度上,你得依赖美术和动画元素,但也可以通过一些可观察的AI行为、敌人、物件布局和场景设置,以及地形探测来完成许多工作。

例如,《机甲指挥官》中的一个任务要求玩家从一艘敌人护航队的相反方向沿河出发。其任务描述要求玩家通过便利的交叉点,在敌人护航队接近退出点前将其歼灭。在关卡早期阶段,玩家的位置远离这条河以及敌人。如果你事先没有阅读任务描述,或者查看战略地图/任务目标,你就不会知道自己的目标是什么,当然也不会产生任务紧迫感。你也不会知道敌人想干什么。而当你探索完毕并且打了数场战役时,你却发现自己毫不知情地失败了。在这种情况下,你有可能重玩一次游戏,并且看看任务描述,但也有可能直接关掉游戏。

后来这个关卡进行了一些改变,在刚开始时就在玩家视野中呈现河流以起敌军护航队的起点。然后你马上就能看到自己的目标,得知它们处于河对岸。你就可以立即调换河岸的导弹和激光火力,并发现护航队并不会减速来攻击你,你还会得知自己正处于一个过河竞赛中,迫在眉睫的任务就是阻断敌人去路。这样整个任务目标和玩法无需只字片语,就能在数秒内一目了然地呈现出来而不至于令玩家困惑——所以最好是为玩家展现可视的揭露内容,位置以及敌人行为。

13)以玩家视角考虑问题

玩家一般会更注意观察出现在关卡“视界”中的物体。视界就是新探测出的地形,以及敌人与玩家交战的地方。视界的变化常会触发玩家的反应,或影响玩家决策,但玩家通常不会察觉到发生于其他区域的变化。

例如,假如有个敌军单位突然出现在之前已探测出的地带中央,玩家可能就不会注意到这一点,除非他们在雷达中看到一个物体尖头信号,或者这个敌军单队袭击了玩家的建筑。而如果敌军单位出现在玩家新探测出的地带,他们很可能马上就会注意到这一情况。与此相似,玩家也只会注意到那些初次看到的建筑。

有些玩家会花一些时间检查之前已探测的地带,但多数人不会这么做,在3D游戏环境中尤其如此。玩家通常只会注意发生在“这里和此时”的事情,所以你得从他们的视角出发设计关卡,确保关卡中的内容不会被他们所忽略。

14)符合玩家的期望

玩家通过会因自己的所见所闻而对你的关卡抱有一定期待。尽管创造玩家从未经历,并且富有挑战性的关卡是一种有趣做法,但也不可忽视他们的最初预期。理解这一点可以让你更好地满足玩家期望,或者超出预期,甚至是彻底颠覆他们的期望。

如果你向他们灌输更多信息,他们在同个关卡中的期望可能就会发生变化。如果你建立了特定期望但却无法将其贯穿始终,这个关卡可能就会让玩家产生困惑或者沉闷无趣。如果你想通过颠覆玩家期望,揭露其意料之外的内容让他们大吃一惊,那就要确保这种设计对关卡的重要性,因为玩家会理所当然地认为这种元素很重要。例如,你告诉玩家他们正处于一个工业建筑中,而他们却并没有看到任何一个工业设施,他们就会感到困惑,就会怀疑自己是否走错屋子,或者自己上错楼层了。除非这种意外之举对玩家来说真的很重要,否则你就应该改变任务描述,或在关卡中植入一些工业机器。与此相同,如果你想给玩家制造意外之感,让他们遇到一种国外技术,你可能就不该将其设置于工业建筑中,因为外国机器与其他机器并没有什么明显差别。你最还是将这种外国机器放置于一个旧车库中,这样才会吸引玩家的注意力。有时候,只有站在玩家的角度才能知道他们的预期是什么,从而识别你的关卡中哪部分内容需要改进。

15)根据中等技能水准来平衡难度

你的游戏玩家是来自技能水平不同的群体。虽然你可以模拟菜鸟或高手来玩自己的关卡,但这种方法可能无助于判断你的关卡实际难度。你可能只会得出“差劲玩家难以过关”这一结论,但这里的问题就在于“高手”和“差劲”都是个模糊概念。

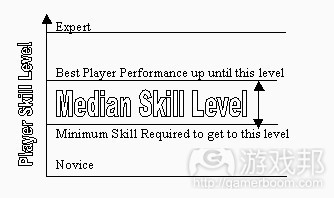

唯一可鉴别玩家技能水平的方法就是,先确定他们技能水平的中间值。玩家开始体验关卡时的中间技能水平,取决于他们玩之前关卡时的低级和高级水准线(游戏邦注:如果是第一个关卡,这一数值就与他们之前所玩过的同类游戏为准)。这样你可以快速根据玩家完成之前关卡的技能来推断他们的最低水平——即最低水准线。而要确定最高水准线,你就得从那些尚未玩过其他关卡的用户中收集反馈信息。这一点很难实现,但如果你是根据公司的测试成员,或者那些只为了免费玩游戏而参与测试的骨灰玩家的水准来获取这一数据,那么你的高水准线就会严重偏向资深玩家。而这些骨灰玩家不但技能高超,而且还善于在游戏过程中向他人取经,所以比起让他们在自己家中玩游戏,群体测试环境并不能试出其真实水平。你最好能够辨别出表现最出色的玩家,以这类群体的技能水平为高级水准线,并以推理法确定低级水准线。这样就可以确立玩家接触关卡时的中间技能水平,并以这两个极端试玩关卡,从而鉴别哪些部分应该调整难度。

16)了解玩家的“锦囊妙计”

每个玩家都有自己的“锦囊妙计”——即解决谜题或挑战的策略、战术。这些妙术包括战斗技巧,侦察方法,偏爱武器,盟军选择,目标选择,建设策略等。设计关卡时,你可以假设这些玩家会使用自己的一些决策来打败你的关卡。但不能假设玩家已经知道某个特定策略的用法。要注意查看游戏早期的关卡,观察玩家是否已经掌握该策略。如果确实如此,那就可以放心使用这种设计,但不要过度使用该策略,因为这样会让你的关卡乏味无趣。如果玩家尚未掌握该策略,那就要慎用,最好不要让它成为你的关卡解决方案。

17)了解玩家所掌握的内容

最好全面了解玩家进入你的关卡中所附带的兵力、武器、口语、技能等级等内容。设计师常会低估或高估玩家开始某个关卡时所带的装备。所以应该研究游戏之前关卡的情况 ,在资产列表查看它们已采纳的内容(详见第9点)。还要查看游戏测试时的相关数值,估算玩家可能承担或建设的内容。然后据此平衡敌军兵力或其他挑战。

由于游戏会随时间发展而变化,因此要关注之前关卡的设计,确保这种变化不会过于突兀——-以免颠覆你的关卡平衡性或破坏整个核心玩法。例如,有个设计师负责之前的一个关卡,他已经植入了会飞的喷射背包这种道具,而你的关卡却已创造了一条宽20英尺的危险河流,需要玩家参与一个桥头遭遇战,那么这就是你的关卡致命伤。

所以要密切关注之前的关卡设计情况,这样才能保证你的关卡完整性。要注意查看资产内容列表,这样才不至于让自己的关卡与他人关卡内容相重复或相冲突。

18)成为玩家的“对手”

关卡设计师在一定程度上得是折磨玩家的“虐待狂”。你得乐于扮演这种坏人角色,从AI角度出发设计内容。这样你才能制作出更具现实感,更易为玩家所理解的对手。玩家通常希望AI可以像人类一样采取行动,如果你编写了一个行为像人类的AI,这将有助于玩家成功制定策略,并深度沉浸在游戏中。这也会在玩家心中激发一点小小的恐惧感,因为他们并没有料到游戏AI居然可以发现他们的脆弱。作为一个坏人,你得让玩家心生恐惧,并充分利用他们的弱点。这样才能让游戏充满挑战性、趣味性和满足感。

19)测试,测试再测试

就确保关卡设计质量而言,没有什么比测试更靠谱了。虽然我将测试列为第19个原则,但实际上玩法测试是一个持续进行的过程。你在制作关卡过程中就得进行测试。如果你在早期设计阶段就辨别出重要漏洞或失误,就能够节省下大量返工的时间。另外,许多关卡设计师想出更多提升关卡的念头时,也需要经常进行测试。记住,只有经过严格的测试,你才能避免自己的关卡出现严重的漏洞,这样才不会在上司或同事面前丢脸。测试关卡也是关卡设计师工作的一部分。

身为关卡设计师最有成就感的一项活动就是看其他人玩你的关卡。此时你不但有机会看到他人的反应(游戏邦注:包括消极和积极反应),还能据此判断他们的体验和你的追求目标有多大差距。你可以观察他们的玩法风格,看他们如何探索和发现不同技巧、谜题、陷阱和奖励。这有利于判断你的关卡对不了解情况的玩家来说究竟有多大难度。你可以由此判断哪些环节太无趣或太难,并相应调整其难度。总有些玩家会有一些超乎寻常的举动,遇到这种情形可以向他们询问原因,要知道这些玩家的回答可能会为你提供一个提升游戏的好主意。总之,观察玩家试玩关卡是你万不可错过的机会。

要始终铭记玩家测试者从来不会有错,尽管他们可能难以清楚解释自己的基本想法,或者提出一些有利于改进关卡的建议。对他们的建议要保留意见,因为他们并不一定是目标市场的用户。有些测试者可能也不是你这类游戏的粉丝,或者他们对这类游戏已经非常熟悉,可能已经无法提供更有价值的难度调整建议。在调整关卡之前,你应该考虑更多测试者的说法,这样才能找到这些反馈的共同点。如果只针对一名玩家的积极或消极反馈调整游戏,这可能会让其他玩家对你的关卡失去兴趣。

20)花时间完善关卡

你投入的时间越多,关卡设计就会越完善。优秀与出色关卡的差别通常就体现在细节上,所以不要吝于投入时间。游戏这种电子媒介的好处在于你可以保存关卡的不同版本并对其进行试验。你可以根据自己脑中的不同想法,或者测试者的反馈尝试不同想法。永远不要满足于自己的关卡设计,除非你已经体验到了自己最初想象中的那种乐趣。要多花时间去想想关卡所缺内容,或者找找阻碍关卡实现那些终极体验的因素。只有你才能够让自己的关卡更上一层楼。

走出“面面俱到”的设计师这一误区

“面面俱到”的设计师通常自认为能够迎合所有人的需求。但作为只有一个脑袋,一颗心的人类,我们怎么能有这种自负想法呢?所以你应该保持谦逊态度,要承认自己的品味与其他人不同,自己并不总是正确的。要乐于接纳他人反馈和新鲜想法,并虚心向更有经验的前辈讨教,否则你很可能失去他们瞄准的市场。

游戏设计是一门难以评判的技术,它无形并且不断发展,也没有专业的院校课程。而“面面俱到”设计师就是利用了这一特点来装腔作势,把自己哄抬为位高权重的人物。不幸的是,这种人在我们行业中随处可见,并且他们总是对你的工作指手划脚。我提到这一点,是希望你不要成为这种人,因为这种人的害处在于其误导性,毕竟让人们觉得你不懂每个玩家的需求真不是什么愉快的经历。

培养关卡设计直觉

关卡设计直觉是招聘者在面试时对你的要求。在一定程度上说,如果你已经设计过一些关卡,他们就会认为你已经具有这种直觉,因为对他们来说,实践出真知。这种直觉就是你从不同游戏和项目中获得的经验,是你作为关卡设计师的与众不同之处。这正是这种直觉让你能够立即将设计理论和原则运用于关卡设计过程。

当你看到其他人的关卡设计,或者自己的早期关卡设计的纰漏时,你就会知道自己是什么时候形成了良好的设计直觉。本系列文章中的原则全部来自我多年制作游戏、犯错误以及获得启发的个人直觉。而作为新人设计师的你也不可能回避错误。不过,如果你从这些经验之谈中学到知识,就能少走一些弯路。希望本系列设计理论和原则能为你的关卡设计事来带来帮助。

游戏邦注:原文发表于1999年4月23日,所述事件以当时为背景。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

11) Make it unique.

Although it is easier said than done, the ability to create unique game elements is very rare these days. Yet at least in level design, you have a chance to combine elements in new ways

and tell different stories. And besides, no good game completely ignores its predecessors or the competition, and you shouldn’t, either. Sometimes it’s useful to play the competition in order to identify aspects of your level that you think are lacking, or spot where your level is better. You often come up with new ideas to add to your design palette. You may find that your level idea has never been implemented before, or you may get inspired to try something new. A level doesn’t have to be completely original to have uniqueness. Your individual tastes will emerge in your design, and that alone will make it unique. Hopefully, the differences will fill a void in your own and other players’ experiences. However you do it, uniqueness sets your level and your game apart from the others, ideally in a positive way.

12) If the player didn’t see it, it didn’t happen.

Don’t assume all players will read dialogue or mission descriptions, and don’t rely on their observation skills, powers of precognition, or capacity for logical deduction to understand what is going on in the level and what they should do. Players must see what is happening to understand it. The old proverb “a picture is worth a thousand words” is entirely accurate in level design. To a certain extent, you are bound by the art and animations, but a lot can be accomplished with observable AI behavior, enemy and object placement and settings, and the revelation of terrain.

For example, a mission from the recent hit MechCommander starts off with you on the opposite side of a meandering river from an enemy convoy. You have to destroy the convoy before it reaches the exit point by racing to convenient jumping or crossing points, as the mission description tells you. In its infancy, the level started the player far from the river and the enemy. If you had not read the mission description or bothered to look at the tactical map or mission objectives, you would not have a clue as to your objectives, and you certainly wouldn’t perceive any sort of urgency. You wouldn’t know what the enemy was up to, or why. By the time you got through exploring and fighting a couple of battles, you’d lose without any idea as to why you lost. Maybe you’d try again and read the mission description, or perhaps you would just turn the game off.

The level was changed to put the river and the starting point of the enemy convoy within your line of sight as the level started. Right away, you see your target and perceive the problem of them being on the opposite side of the river. Soon after you exchange missile and laser fire across the river, you realize that the convoy will not slow down to attack you, and you find yourself in a race to cross the river and cut them down before they get away. The whole objective and core game play of the mission is revealed in seconds without any words or confusion – just with insightful revelation, positioning, and enemy behavior.

13) See through the player’s eyes.

Players usually watch most closely those objects that appear on a level’s “event horizon.” The event horizon is where new terrain is revealed and where enemies are engaging the player.

Changes in the event horizon often trigger a reaction from players or influence their decisions, and changes elsewhere may not get noticed immediately.

For instance, if an enemy unit suddenly appeared in the middle of previously revealed terrain, it may not attract the player’s attention, at least until a blip appeared on the radar or the new unit attacked one of the player’s buildings. However, if the enemy unit appeared where new terrain was being revealed, it’s likely that it would be noticed right away. Likewise, a building isn’t really looked at except when it’s initially revealed.

While some players spend time examining previously revealed terrain, most people do not, and it becomes even less likely when the game takes place within a 3D environment. Players usually only observe what is in the “here and now,” and you should put yourself in their position to ensure that you don’t put imperceptible events in your level.

14) Fulfill player expectations.

Players will have certain expectations about your level based on what they may have already seen or been told. While it is fun and challenging for a player to experience the unexpected, you have to be aware of their initial expectations. This makes it easier for you to ensure that you are either meeting those expectations, surpassing them, or tossing them out altogether.

Players’ expectations can change throughout a level as you feed them more information. If you build up certain expectations and fail to follow through on them, the level can seem confusing or barren. If you elect to surprise the players by tossing out their expectations and revealing the unexpected, be sure it’s important for your level, because the players will certainly perceive it as important. For example, it you tell the player that they are in an industrial building and they don’t find any industrial equipment, they’ll get confused. They’ll wonder if they are in the right building or if they’ve missed any floors. Unless it’s important to the plot to surprise the player, you should either change the mission description or insert a few industrial machines into the level. Likewise, if you want to surprise the player with the existence of alien technology, you probably wouldn’t want to put it in an industrial building, because alien machines wouldn’t necessarily look much different from other machinery. You would be better off putting alien machine in the cellar of an old barn, where it would really grab the player’s attention. Sometimes, it’s only by taking the player’s perspective that you can perceive their expectations and identify aspects of your level that need to be improved.

15) Balance the difficulty for the median skill level.

Players of varying skill levels will play your game. While you can try playing your level as a bad player and again as a good player, you will probably not draw any significant conclusions about your level in this way. You’ll probably just conclude that “players who are bad should expect to lose.” The problem is that “good” and “bad” are vague terms.

The only way to identify what skills players will really have when they begin your level is to determine their median skill level. The median skill level of a player starting your level can be determined by using low- and high-water marks that previous levels have established (or, if it’s the first level, from previously played games in the same genre). You can quickly deduce what minimum skills a player has based on what it took to complete the previous levels – that’s your low-water mark. To determine the high-water mark, you have to gather feedback from people who haven’t played any level beyond yours. This can be difficult, however – if you are basing the high-water mark on the abilities of individuals in your test department or the extreme game geeks that show up to the focus groups for a free game and pizza, your high-water mark might be skewed too far towards the extremely talented players. These hardcore players are not only talented game players in their own right, they also tend to learn from one another while playing, so no one is ever going to play as badly in a group testing environment as they would if they were playing the game by themselves at home. You’re better off identifying the best player, setting that person’s skill level as the high-water mark, and using deductive reasoning to determine the low-water mark. This establishes the median skill of players approaching your level, and with this knowledge, you can play test the level at both extremes and identify where it needs to be made easier or harder.

16) Know the players’ bag of tricks.

Each player has his own “bag of tricks” – strategies and tactics for solving puzzles or challenges that are put before him. This bag of tricks includes battle tactics, scouting methods, preferred armament, their choice of allied forces, their choice of targets, their construction strategies, and so on. When designing a level, you can assume that the player will use some of the tricks from his bag to beat your level. However, don’t assume that a player knows a one particular trick yet. Look at the earlier levels in your game and see if players have been taught the trick yet. If they have, feel free to use it, but be careful not to rely on an overused trick, as it makes your level boring. If players have not been taught the trick yet, then be careful not to base your level’s solution on its use.

17) Learn what players may bring to the fray.

Have a thorough understanding of what players bring with themselves to your level, in terms of forces, weapons, spells, skill ratings, and so on. It’s not uncommon for designers to underestimate or overestimate what players will be equipped to do as they begin the level. Study the previous levels in your game. Look at the asset revelation schedule (see rule #9). Examine play testing statistics. Estimate what players may be able to afford or build. Then balance the enemy forces and other challenges accordingly.

As the game evolves over the course of time, keep an eye on the design of previous levels and make sure that they don’t change significantly – that can throw off the balance of your level or spoil your core game play. For example, if a designer working on the level prior to yours arbitrarily threw in a jet-pack, and you had already created a treacherous, 20-foot wide river to coax the player into a cool bridge encounter, it would ruin your whole level.

Be a watchdog over the design of other levels, because it will protect the integrity of your level. Worship the asset revelation schedule so that you don’t ruin someone else’s level, and nobody can spoil yours.

18) Be the adversary.

To a certain extent you have to be sadistic to the players. You should enjoy being the adversary, and think from the AI’s perspective. This will help you make much more realistic opponents that a player can understand. Players naturally put a human face on the AI, and so they expect the AI to behave like a human. When you script the AI to behave in a human fashion, it helps players successfully strategize and often draws them deeper into the game. It also evokes a little fear in players, as they don’t expect a game AI to recognize their weaknesses. As the adversary, you need to provoke fear in players and prey on their weaknesses. It’s what makes the game more challenging, fun and fulfilling.

19) Play test, play test, and play test some more.

Nothing surpasses play testing when it comes to ensuring quality level design. Although I’ve listed it as the19th rule, play-testing should be an ongoing process. You need to test your levels as you make them. It will save you a lot of time reworking your level if you can identify a significant bug or flaw in your thinking early in the design process. Plus, play testing is often where many level designers come up with some of their best improvements to levels. And don’t forget that only through rigorous play-testing you can spare yourself the embarrassment of your boss or your coworkers finding some really heinous and obvious bugs in your level. Testing your level is part of your job.

One of the most rewarding activities in level design is watching other people play your level. Not only do you get an opportunity to see their reactions (both positive and negative), but you can gauge how close they come to the experience you strove for. You can observe their play styles, see how they explore and discover the various tricks, puzzles, traps and rewards. It helps you see how difficult your level is to people who don’t already know the solutions and don’t necessarily have your play skills. You can identify where your level is too boring or difficult, observe solutions to puzzles that you didn’t expect and thereby make them easier, or harder. There’s always a player who will do the unexpected, and when you come across this situation, don’t be afraid to ask them questions like, “Why did you go there?” The player may provide you with a great idea for improving your level. Watching a player test your level is definitely an opportunity you should never pass up.

Always remember that play-testers are never wrong, though they may not be able to clearly explain the basis for their opinions or offer good suggestions for improving your level. Take their advice with a grain of salt, because they are not always the target market or the target skill level. Some of your testers may not be big fans of your type of game, or they might have played the game so much that they’re no longer good sources of advice when it comes to the game’s difficulty. You should get input from as many play testers as you can before you change your level, so that you can see if there’s consensus in the feedback. Reacting to only one player’s response, whether positive or negative, can spoil your level for the other players.

20) Take the time to make it better.

The more time you spend working on a level, the better it can get. It’s often the subtler details that separate a good level from a great one, so take some time to put them in. It’s one of the finer pleasures of the level designer’s job to perfect a setting or the choreography of a battle. The beauty of the electronic medium is that you can save different copies of your level and experiment with them. Try out different ideas from your own twisted mind or based on feedback from play testers. Don’t ever be content with your level until you’ve experienced the fun you originally envisioned. There’s often something you can do in your level to get that vision across. Take the time to figure out what’s lacking or what’s preventing you from having that ultimate experience. You are the only one who can make it better.

The Myth of the “Every-Man” Designer

The “Every-Man” designer is the person who thinks that he or she knows what every person wants in a game. Being human and of only one mind and heart, this is a very pretentious assumption. You should have the humility to recognize that your tastes differ from others and that you are not always right. Keep your mind open to feedback and fresh ideas, and consult with people who may have more experience than you. If you do not, your games will miss their intended market.

Game design is a very hard skill to judge, being intangible, evolving, and not taught in any school. The “Every-Man” designers take advantage of this by putting on airs of great skill to put themselves into positions of power. Unfortunately, our industry is full of such people and they are often in a position to judge and change your work. I hope that by mentioning this here, early in your career, that you will not become one of them, because it can be a very unpleasant realization for you and your company that you don’t know what every player wants.

Developing Level Design Instincts

Level design instincts are what employers look for when they interview you. To a certain extent, employers assume you have some of these instincts if you have designed any levels at all, for they only come from practice. They are what you take from game to game and project to project, and they’re what make your job so special. It’s these instincts that let you immediately apply design theories and rules on the first pass of designing a level.

You’ll know when you have developed good instincts when you can look at someone else’s level, or an early level of your own, and the mistakes will glare at you. All of the rules in this series of articles came from my own instincts which I developed over years of making games, making plenty of mistakes, and having plenty of realizations. You, as a beginning designer, will make plenty of mistakes. However, hopefully you will learn from these experiences and you will stick with it. Hopefully these level design theories and rules will get you a head start on a satisfying hobby or career in level design.(source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号