论述游戏限时机制的潜在原理和设计准则

作者:Eric Schwarz

游戏玩家最讨厌的莫过于过于仓促赶时间。尽管计时器由来已久,几乎随游戏同时出现在这个世界上,而且在80年代被街机和家用主机游戏广泛采用,但现在它已经成为没落的游戏玩法元素,至少没有任何现实意义。

我想花点时间来分析计时器如何在游戏中发挥作用、为何玩家普遍不喜欢计时器,以及如何以其他方式将计时器背后的基础设计想法和机制有效地在游戏中执行。

计时器由来

正如上文所提到的,计时器深深扎根于街机游戏。在街机的黄金时代,计时器的存在可以确保玩家不断将硬币投入游戏机中。许多街机游戏通过让玩家不断尝试(游戏邦注:如《龙穴历险记》)和延续游戏进程(游戏邦注:多数打斗游戏)的设计来确保玩家持续支付金钱,计时器也是设计师实现相同目标的一种方法。如果第2关的最终BOSS没有让你倒下,那么5分钟的时间限制总会迫使你投入更多金钱来体验第3关。

(在街机游戏流行的年代,时间限制并非以有趣的游戏玩法功能的形式而存在,更多是为了让玩家往机器中投更多的金钱。许多游戏用生命值条来替代数字化的计时器。)

在家用主机中,时间限制设计存在了很长一段时间,随后被遗弃。80年代的多数图标平台游戏都包含时间限制,有些游戏的时间限制在各个关卡有所不同(如《超级马里奥兄弟》),有些游戏的时间限制是固定的(如《Sonic the Hedgehog》)。从某种程度上来说,时间限制是街机世界的遗产,但是它也有新的作用——改善游戏玩法。

《Sonic the Hedgehog》中较长的10分钟游戏时间限制的存在并非出于盈利目的,而是为了增加关卡的紧张感。这是款以速度取胜的游戏,因为计时器的存在,所以索尼克不能回头拾取所有的能力提升和可收集道具。计时器产生的压力感足以推动玩家前进,即便玩家几乎不会受到时间耗尽的威胁,因为环境中的危险和敌人已经足以让玩家的成功之路充满障碍。

行走的钟表

问题在于,多数人讨厌时间限制。在某些情况下,看到倒计时会让人产生不适感,参加过考试的人应该都知道,而现在这种不适感进入了电子游戏领域。在家用主机流行的年代,时间限制产生的挫败感往往大于趣味性,玩家的厌恶感仅次于生命数限制这种过时做法。

计时器还会产生其他感觉,比如我们感觉有个外在实体正在监视我们,监管我们的每次移动并默默进行评判。结果,计时器的存在让我们不是专注于正在做的事情,而是过多地考虑正在失去的东西。每个动作都会耗费时间,这些时间可以用来开展其他动作,而只有行走的钟表知道我们是否做出了正确的选择。一时间,游戏变得过分注重于表现。

(求生恐怖游戏通常并没有字面的倒计时,但是同样能够营造压力和恐慌感,因为监管玩家动作的潜在机制与上述相似。)

这种不舒适是玩家讨厌计时器的本质原因,而并非计时器本身。当我们将玩家对计时器的厌恶缩减到这种情感反应后,我们就能够知道用其他方法来呈现计时器的功能,同时杜绝让玩家产生同样的情感反应。此外,这使得我们可以更好地操控场景,构建我们真正想让玩家体验的感觉。

求生恐怖游戏《寂静岭:破碎的记忆》是最佳的范例。在这款非传统游戏中,大量紧张和恐惧感直接来源于玩家被迫甩开速度更快的敌人。虽然没有字面上的时间限制,但是产生的紧张感与传统做法相比毫不逊色,因为每个动作感觉都相当重要,随着游戏的紧张,允许犯错误的机会越来越少。相比之下,《心灵杀手》创造的只是恐惧感,缺乏慌乱的成分。因为没有强大的时间管理元素,这款游戏产生的害怕体验不及前者。

时间机制

时间是我们必须在游戏中管理的最基础性资源之一。即便是那些我们在体验时通常不会考虑到时间的游戏,也都有时间管理成分,比如第一人称射击游戏系统通常有精确度和反应速度与伤害相关的系统,回合制战略游戏通常以回合计时器作为时间限制的形式,部分游戏中超级能力使用后会产生一定的冷却时间等。表现时间限制的方法有很多种,但是主要目标都是通过向每个动作提供次级游戏玩法结果,从而营造紧张感。

理解了计时器的重点不在时间而在于限制玩家的可选项范围,这样才算是真正明白计时器为何能够在游戏中发挥作用。通过这个角度来看,就很容易发现游戏中的时间限制,无论它们是否具体清晰地呈现。它往往成为游戏体验深度构建的一部分,为那些可能变得相当独立的机制提供额外的结构。

(长期和短期时间管理以及它们与其他资源间的相互作用,奠定了《星际争霸》的紧张战略游戏玩法。)

《星际争霸》中军队的组建不再只是获取足够的资源并生产制造部队,你需要以尽可能高效的方法实现目标,赶在敌人之前优先组建好军队。这种紧张以及对做错动作和决策的恐惧成为了《星际争霸》战略的驱动因素。所有单位和建筑的选择只有在特定的背景下才有意义。

从这里我们就能够发现,时间能够进一步拓展游戏玩法。不同单位的建造时间不同,通过它们之间的相对效用和能力取得平衡。战略的风险性取决于它们所耗费的时间。改变不同单位的护甲或生命值回复速度能够或多或少地影响单位的长期作战能力,也会让玩家在决定是否将它们送到前线时考虑再三。当然,这只是一款游戏,但它同样适用于所有类型的游戏,从射击游戏到平台游戏再到解谜游戏。

时间限制的处理

当然,如果你必须在游戏中设置时间限制,那么在合适的背景下它仍然能够发挥作用。以下是部分可参考的规则,确保时间限制能够呈现出一定的趣味性:

1、不在计时器中设置绝对失败的状态。如果玩家犯了错误或在游戏中止步不前后耗费了时间,那无疑是件令人沮丧的事情。如果再配上游戏结束屏幕、进程丢失以及需要玩家重玩前面的关卡,就更容易让玩家反感。比如,在《暗黑破坏神3》中,有个挑战是在大门再次关闭前到达某个隐藏地下室,但是如果失败,不会出现“石头落下,所有人死亡”的场景。

2、指明击败时间的好处或失败的风险。如果玩家对危险毫无所知,那么计时器的设置就变得毫无价值。这种方法可以运用到游戏玩法和故事中,比如《杀出重围3:人类革命》会惩罚玩家在充满敌意的情景中花费过多的时间,但是在惩罚玩家之前,游戏会不断强调加快速度的重要性。

3、提供奖励,杜绝惩罚。计时器本身已经具有惩罚的成分。如果玩家能够在事件耗尽之前完成目标,这是玩家技能娴熟的体验,应当获得奖励。失败并非总是因为玩家技能的不足,虽然有时可以进行适当的惩罚,但是惩罚应当仅限于玩家犯下错误的地方,而不应波及到之前付出的努力。

4、提供其他选择。尤其在长期计时器(游戏邦注:如食物和饥饿机制)的设计中,玩家总是会发现自己身处某个意料之外的情境,而这可能并非是他们自身的过错。所以,游戏应当向玩家提供可选的其他惩罚措施(游戏邦注:将一种资源转换成另一种资源,比如用金币购买时间)或挽救错误的方法(游戏邦注:比如玩家可以完成一个可选挑战来获得更多的时间)。

并不是说时间限制总是应当遵从这些原则。有些游戏从冷酷的时间限制中收获巨大的利益。我在游戏中体验过的部分最有趣的经历来源于对时间限制的管理,比如在《辐射》中,在我第一遍玩游戏时,我不得不匆忙将Water Chip带回到13号地下室,从而杜绝游戏失败。《潜行者》系类游戏也让玩家感到很满意,它提供了大量有关资源管理的挑战,如果没有做好恰当的准备就会被杀死。这样的设计并没有问题,只要玩家预先知道如何才能生存下去,无论是通过具体的教程还是逐渐加深的游戏难度和深度得知。

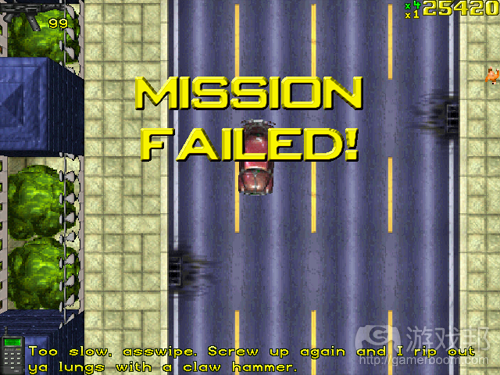

(《侠盗猎车手》中严厉的时间限制人所共知,但过于严格和强制性本质使其产生的挫败感大于趣味性。)

关键在于,要记住计时器永远不应呈现出不公平的一面。我还记得《侠盗猎车手:罪恶都市》为某些极为困难的挑战强加严格的时间限制,导致故事无法继续发展下去,毫无趣味性可言。在古怪的控制和脚本化事件之间,这样的时间限制几乎可以算是设计师的恶意安排,多次的重复尝试很快便会使创新感荡然无存。

最后,我想要说下越来越多现代游戏开始采用的“反时间限制”。游戏采用的不是倒计时,而是逐渐增加来记录你的最终分数。无论是《子弹风暴》中的关卡完成时间排行榜还是《超级食肉男孩》中需要快速反应才能到达的限制性奖励关卡,这些计时器都让玩家觉得更为公平。玩家不会因为时间限制而死亡,但是他们可能会因此而无法解锁奖励内容或取得高分。这样的设计能够让玩家持续玩游戏并提高自己的技能,而不会产生挫败感。

总结

看到游戏设计中早期的做法转变成如此精妙和柔和的机制,确实是件很有趣的事情。虽然有些人可能坚持认为计时器是呈现挑战的绝佳方式,但是同所有游戏机制一样,认识到其发挥作用的潜在原因是很重要的,比如为何会产生时间限制机制、它们应当如何适应新形势和设计以及如何来避免让玩家产生不必要的挫败感。

我也很好奇,想知道将来开发者会通过哪些更有趣的方法来融合时间限制。我在孩提时代玩过的许多游戏都依赖于明晰的时间管理,但许多游戏近些年来已经消失。层次化资源管理是趣味系统设计的核心,添加一个或两个长期或短期的时间限制,往往能够彻底改变游戏玩法的本质。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Ticking Clock: Understanding Time Limits

Eric Schwarz

There are few things gamers seem to hate more than being rushed. Although timers have historically been with games since nearly the beginning, and were a staple of arcade and home console titles throughout the 80s, in modern times it’s been an element of gameplay that has fallen out of fashion – at least, in any explicit sense.

In this article I’d like to take a moment to examine how timers work in games, why players usually don’t enjoy them, and how the fundamental design ideas and mechanics behind timers can be effectively implemented into a game in other ways.

Long Time Past

Timers, as mentioned above, have their roots in arcade games. Back in the golden age of arcades, timers existed as a second way to make sure players kept plunking quarters into the game machine. Just as the design of many arcade games was centered specifically on trial-and-error (Dragon’s Lair) and sheer perseverance (just about any brawler) to make sure players kept paying, timers were a more brute-force method of achieving the same goals. If the end boss on level 2 didn’t get you, then you could be sure the five-minute limit would force you to deposit more money by level 3.

(In the days of arcade games, time limits were less a function of interesting gameplay and more about getting players to cram more quarters into the machine – in many cases the health bar itself was a substitute for a numeric clock.)

On home consoles, time limits persisted for a very long time they were obsolete. Many of the most iconic platform games of the 80s included time limits, some of them variable with each stage (Super Mario Bros.) and some of them fixed (Sonic the Hedgehog). The time limit was to a degree a legacy of the arcade world, but it also served a new function – to improve gameplay for its own sake.

The lengthy ten-minute clock in Sonic the Hedgehog existed not for profiteering reasons, but to add a feeling of tension to stages. It was a game all about speed, and as a result of the timer, Sonic couldn’t pick up every last power-up and collectable. The “feel” of being under pressure was enough to push players onward even if they were almost never in danger of running out of time – environmental hazards and enemies were enough to do put success in jeopardy already.

The Ticking Clock

The problem is that most people hate time limits. The feeling of a ticking clock counting down constantly is one that borders on torturous in some cases, as anyone who’s taken a timed exam will know, and that carries over into the realm of videogames. In an era of home consoles, time limits are often more frustrating than fun, feeling antiquated next to other relics of the past like limited lives.

There’s a certain Otherness to the timer, a sense of a foreign entity looking over us, monitoring our every move, and casting silent judgment. The timer isn’t just about what we’re doing, but what we’re missing as a result. Every action loses valuable time that could be spent elsewhere… and only the ticking clock knows if we made the right choice. Suddenly gaming is about performance, in more ways than one.

(Survival horror games don’t often have literal timers, but the exact same stress and panic can be created because the underlying mechanics governing player actions are very similar.)

It’s this discomfort that is the essence of the timer, not the timer itself. When reduced down to such an emotional response, suddenly there are all sorts of other ways that we can create the mechanical function of a timer, without necessarily creating the same emotional reaction in players. Moreover, this allows us to better manipulate scenarios to engineer the feelings we actually want players to experience.

One of the best examples of this can be seen in a survival horror title like Silent Hill: Shattered Memories. In this rather unconventional game, much of the tension and fear is a direct result of being forced to run from enemies that are faster than you are. While not a literal time limit, that feeling of intense distress comes on in full force because every action feels significant, and there’s less and less margin for error as the game goes on. Contrast this with Alan Wake, where a more pervasive feeling of dread is created, rather than any sort of panic – without a strong time management element, the game isn’t so much outright scary as it is a page-turner.

Mechanics of Time

Time is one of the most fundamental resources we have to manage in games. Even games we usually don’t think about time in are heavily moderated by it – first-person shooter game systems are usually a function of accuracy and reaction speed vs. damage taken, turn-based strategy games usually have a form of time limit in turn timers, cooldowns before you can use your super ability again, and so on. There are any number of ways time limits can be expressed, but the main goal is always to create a sense of tension by providing a secondary gameplay consequence to each action.

Understanding that timers are not about time and more about limiting the range of a player’s available options before failure is integral to getting why timers work. Seen through this lens, it’s hard to un-see time limits in games whether they’re explicit or not. It often forms much of the depth of an experience, and gives additional structure to what would otherwise be a fairly isolated and limited set of mechanics.

(Long-term and short-term time management, and their interplay between other resources, is what defines StarCraft’s intense strategic gameplay.)

No longer is building an army in StarCraft about simply farming the right amounts of resources and building up forces – now it’s about doing so in the most efficient way possible, to ensure that the enemy doesn’t do it first. This strained, tense relationship, the fear that every action could be the wrong one, is what drives the strategy of StarCraft. All the selection of units, buildings, and so on only gains meaning through the context of time.

From there, it’s simple to see how time can offer further gameplay propositions. Different units can take more or less time to build, balanced out by their relative effectiveness. Strategies are more or less risky due to how much time they consume (the Zerg Rush being the most classic gamble). Changing the shield or health regeneration rates on different units can make them more or less compelling to maintain long-term, and also make players think twice about sending them in on the front lines. And of course, this is just one example of one game – this applies equally to everything from scrolling shooters, to platform games, to puzzle games.

Handling Time Limits

Of course, if you absolutely just have to have a time limit in a game, then it can still definitely work when given the right context. There’s a few general rules to follow that will ensure time limits stay fun.

Never attach an absolute fail state to a timer. If the player makes a mistake, gets stuck, etc. and runs out of time, that’s frustrating. Combining that with a game over screen, lost progress, the requirement to replay a section of gameplay? Even more annoying. For example, in Diablo III, there’s a challenge to reach a hidden vault before it closes again, but this doesn’t result in a “rocks fall, everyone dies” scenario.

Telegraph the benefits of beating the clock, or the risks of failure. If the player doesn’t know what’s at stake then it’s not worth bothering with a timer at all. This can apply both to gameplay and story – such as Deus Ex: Human Revolution punishing the player for spending too much time smelling flowers during a hostage situation, but only after reinforcing the importance of being quick.

Offer rewards, not punishments. Timers are already punishing in themselves. If a player is able to complete a goal before a timer runs out, that’s a sign of skill, and should be rewarded. Losing out isn’t always a function of a lack of skill, and while sometimes punishments are fine, usually the punishment should come from what the player is missing out on by losing, not by crippling them further.

Give alternatives. Especially in the case of long-term timers (such as a food and hunger mechanic), players can always be caught with their pants down in a way that is unpredictable and may not be their fault. Rather than face the prospect of hours of lost game time for simple forgetfulness, offer the ability to take an alternate punishment (exchange one resource for another, i.e. time for gold), or make up for the mistake (complete an optional challenge to gain more time back).

This isn’t to say that time limits should always conform to these guidelines. Some games benefit immensely from their brutality. Some of the most fun I’ve had with games has come from the result of mis-managing time limits, such as in Fallout, when during my first play-through I had to rush to bring the Water Chip back to Vault 13 before a game over scenario. The STALKER series is immensely satisfying and provides a great deal of challenge in resource management, and failure to prepare properly will get you killed – there’s nothing wrong with that so long as players are well-informed of how to survive in the first place, whether through explicit tutorials or a gradual ramp up in difficulty and game depth.

(Grand Theft Auto is known for its stringent time limits, but they tend to be more frustrating than fun due to their incredible strictness and mandatory nature.)

The key thing to keep in mind above all else is that timers should never be unfair – I have many memories of Grand Theft Auto: Vice City imposing strict mandatory time limits on extremely difficult challenges before story progress could continue, for instance, and it was no more fun a decade ago than it is today. Between the squirrely controls and scripted events designed specifically to force mission restarts, time limits of that nature were nearly malevolent on the part of designers, and the novelty soon wore off in the face of sheer repetition.

One last thing I’d like to draw attention to is the “inverse time limit” that some more modern games have begun to sport. Rather than ticking down, a timer ticks up to document your final score. Whether that’s Bulletstorm’s level completion time leaderboards or Super Meat Boy’s limited-access bonus stages that require quick reflexes to reach, these timers feel far more fair for players. Players won’t ever die as a result of those time limits, but they might miss out on unlocking optional bonus content or reaching the high scores. This provides an impetus to keep playing and mastering the game rather than a sense of frustration.

Closing Thoughts

It’s been interesting to see such a staple in gaming’s early days transition into a much more smartly-utilized, softer mechanic. While some purists might insist that timers are great to have around as a pretense of challenge, like all game mechanics it’s important to recognize the underlying reasons for why time limits exist in the first place, and how they can be repurposed for new situations or even camouflaged to avoid frustrating players needlessly.

I’m also curious to see developers take time limits in more interesting directions in the future. While many of the games of my childhood depended upon explicit time management, much of that has disappeared or been obfuscated in recent years. Layered resource management is the core of interesting systems design, and adding just one or two time limits, in both the long or short term, can often completely change the nature of gameplay. (Source: Gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号