阐述游戏化现象所蕴含的5大设计原则

作者:Tim Richards

游戏化。当我们看到这个词的时候,都会立即想到其中还蕴含着许多未知的内容。它的运用相当广泛,但却鲜有明确的含义。众人对游戏呈现出的好奇和想象力,使行业误认为所有人都可以付费将内容“游戏化”。

确实,商业社会注意到了《Farmville》中的邀请和Foursquare的徽章,认为将内容游戏化就是模仿目前Facebook游戏中普遍采用的做法。事实上,事情并非如此简单。

注意力经济规则

事实在于,游戏机制是单纯的注意力经济规则。如果品牌希望让消费者喜欢并得到其关注,他们需要做好采纳游戏原则后获得成功和遭遇失败的双重准备。品牌持有者会很快看到,虽然传统广告(游戏邦注:任意平台上的传统广告)也会产生用户期望,但游戏化带来的是逐渐增长的数字化或互动责任,持有者需要满足消费者的期望或对其做出的承诺。在品牌世界中,这种交易已证实不仅影响品牌感知,而且还会影响许多有形的结果,比如消费者购买量的增加和口舌传播带来的新销量。确实,在这个逐渐繁荣的数字化世界中,游戏化能够带来很丰厚的回报。

那么,品牌游戏如何能够产生如此成功的营销成果?《Nike +》与其他的步行奖励有何不同之处?麦当劳的《大富翁》游戏究竟有着怎样的魔力?当其发挥作用时,游戏机制或品牌代言几乎没有被人们注意到。当你产生行动的动机时,个体机制只是游戏的一部分。成功的游戏化项目一般都会体现以下几个人们未注意到的原则:

1、厌恶损失:前景理论、风险和奖励

多数人在追求获得之前会趋向于避免损失,用回避痛苦来驱动用户比用追寻乐趣要有效得多。Zynga游戏《Farmville》就用许多方法来利用这一点,首先是创建初始农场背景和固定数量的货币。

玩家必须使用货币来种植和收获作物,然后赢取更多的货币。如果你不访问农场或照看作物,它们就会枯萎和死亡。产生驱动力的并非Zynga货币的价值,而是作物的潜在损失可能性。同样,Foursquare奖励中的品牌参与显得不温不火。成为应用中的市长并没有真正的价值,但是一旦成为市长之后,维持这种凌驾于同事、好友和陌生人之上的感觉驱动着人们不断登陆应用和保持签到行为。

因为这些决定理论只是描述人类行为,所以不适宜用来制作游戏化行为,但是它的确提供了重要的规则,让游戏制作者了解人们评估风险、潜在奖励和效用之间关系的方法。当与游戏中地位、声望和反馈等其他元素相结合时,这些原则显得特别强大,导致玩家产生行动或互动的动机。

2、渗透经济:地位、声望和竞争

通过我们自己与他人的比较来评估自己的价值,这有时看上去似乎更像是社交行为,而不是游戏设计中的鼓励部分。我们先撇开竞争的本源,只探讨让社交化成就鼓励人们不断确定明确的目标,这也是优秀游戏化的另一个必要元素。

(《Call of Duty: Elite》是玩家社区以动视划时代射击作品为基础制作的产品。它将游戏数据融合到社交图表中,帮助你获得更好的互动体验。)

使用这项原则首先是理解地位、声望和竞争的概念。通过社交将玩家联系起来能够驱动玩家持续性的参与。近期PSFK报告强调,部分产品使用同龄压力来驱动玩家参与:某太阳能充电器发布使用者的“绿色能源”等级;Reebok的《Promise Keeper》应用广播奔跑者运动的意图并用GPS来督促他们完成目标;某日本闹钟应用在用户点击“小睡”按钮时通过Twitter发送这个行为。

可视经济

接下来我们要专注于这个原则的第二部分,也就是可视经济。个人相关排行榜、社交竞争和地位比较都是绝妙的方法,让人们知道存在运转中的经济系统。徽章需要有某些共同的象征性价值。

开发出经济意味着需要清晰呈现价值互换和货币,确保玩家群体足够庞大,使得玩家有机会与他人交换价值,无论这样的价值是否通过货币来呈现。并不是说所有的游戏经济都只能通过敌友竞争来驱动。作为游戏管理者,你的责任是确保玩家能够找到交换价值的人或物,设定足够的非玩家角色群体和特定货币交易率、合理的声望折扣和兑换以及以稀有度来衡量道具价值的玩家和游戏控制经济(游戏邦注:《魔兽世界》中有许多可供借鉴的方法)。游戏必须设置在虚拟世界中可稳定获得的货币。否则,就不存在所有的经济。如果没有经济,玩家就会失去游戏动机。

3、曝光:惊喜和愉悦

前景理论专注于阐述人们如何基于自身对事物的理解来权衡风险和奖励并做出决定,这个游戏元素更多讲述的是进展性披露和基于故事的曝光。这是典型的故事讲述模式:叙述者知道的比听众更多,披露间的相互作用造成的紧张感使游戏玩家不断回到游戏中。事实上,这是将曝光同另一个著名游戏机制相结合的绝佳机会,那就是周期性事件。玩家可能会周期性地回到游戏中收取产出物或奖励,而这提供了进展性披露未公开情节、新玩法区域和额外功能的绝佳机遇。

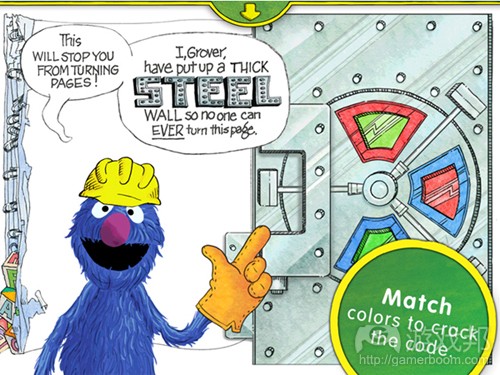

(在芝麻街的《Monster at the End of This Book…》iPad应用中,互动游戏由故事来揭开。儿童跟随Grover的经典冒险现在需要轻微的游戏互动来取得进展。)

4、希望:反馈、触发和必然

这项原则不仅仅是这个列表中的一分子,而且更具策略性。人们需要知道自己能够带有何种期望,可能存在障碍的位置以及上次动作所产生的影响。通过持续性的交流机制来实现即时异步和为玩家提供清晰的反馈。

游戏化交流意味着在令人惊讶的对话中设置一定的节奏和必然。随着玩家做出动作,分数会逐渐增加,这是个清晰和持续性的奖励系统。规划特定阶段的交流能够创造触发动机的机会,即便我们只是向玩家提供平凡的更新内容。玩家的相互作用和对话应当总是融合系列故事、效用交流以及同玩家社区的交流。这可以使玩家感受到持续且清晰的反馈,从而使之产生挑战既有价值又可实现的期望。

比如,当塞尔达的血量从5减少到1时,游戏会响起令人痛苦的音乐,这种设计显然是为了提高玩家的心跳,游戏中的生命值系统传达了带有兴奋感的希望。玩家希望能够回复生命,在此过程中受到的更多伤害会增加恢复的紧迫性,玩家却始终保持着获得更多生命值的目标,这样才有足够的资本去探索更深层次的未知区域。这种反馈让人类在游戏中的感觉好于现实生活。Jane McGonigal在她的TED演讲中提到:“游戏能够让世界变得更好。”这种持续性的反馈在提升人类表现和能力方面起到很大的作用。

(《塞尔达传说》的故事和冒险类似于《龙与地下城》,但是夹杂着许多小谜题和互动动作。随着游戏的进展,角色的生命值总量增加,但怪物的伤害量也随之增加,探索的难度也有所增强。)

5、史诗:故事、连接、真相和含义

我们继续深入探讨McGonigal女士的想法,游戏原则和决定理论在积极心理上存在交叉点,那就是对快乐的研究。当我们参与到游戏中,我们的学习中枢被激活,我们的表现获得提升,我们感受到了乐趣。

为什么我们会喜欢玩呢?因为我们有克服挑战的希望。事实上,或许这就是游戏世界与现实世界中的问题解决相比的魅力所在:我们知道游戏中所有的问题都是由人类设计而成的,因而可以被解决。只要游戏故事与人类社会中的真实体验相符,我们就会自动将自己同故事连接起来。

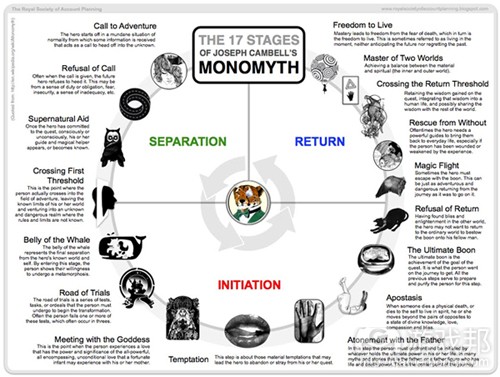

(Joseph Campbell的《英雄的旅程》遵循人类的叙事方法,呈现各种文化和数个世纪以来的故事和神话。Campbell在自己所著书籍《千面英雄》中描述了这种故事呈现样式。)

这里的游戏规则很清楚。玩家必须在挑战中感受到自己的存在。大脑中竞争中枢的开启需要游戏传输含义和地位:提供反馈,呈现触发,进展性披露情节并阐明经济。要实现所有这些内容,含义是最重要的,故事必须有个核心点。无论是休闲还是硬核,都必须存在真相,而且能够互动体验。史诗般的冒险故事能够创造超越冲动的含义,而轻型和休闲互动能够使用简单的节奏和幽默来让玩家做出响应。

人们通过《英雄的旅程》等故事讲述模式来评估交流,可能还会在故事和他们自身的生活和体验之间寻找真相。这是下一步的目标:将不断成长的游戏玩家世界同现实世界挑战连接起来。PSFK所发布的《Future of Gaming》报告和Jane McMonigal的想法都表明,将来人们会使用游戏结构来解决饥饿、贫困和肥胖等现实世界中的问题,用简单的方法来应对许多棘手的问题。这会有效吗?或许会有效,但其效用取决于现实世界挑战与趣味性机制的相符程度。

为什么我们会喜欢玩呢?或许意大利作家Italo Calvino给出了最好的答案:“在生活的压力下寻找轻松的空间。”

我们很喜欢竞争和玩,这一点是毫无疑问的。马斯洛提供了一个模型,可用于理解我们许多行为背后的驱动力。真相在于,该模型中的每个层面依然存在竞争。人类自我保护和发展的内在驱动想法就会产生竞争。

《Nike +》的内涵是什么呢?竞争和自我实现,不是吗?

Facebook呢?不只是个社区,其中还包括竞争性乐趣、竞争性喜剧和竞争性旅行相片记录冒险。

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2012年4月6日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Principles Of Gamification

Tim Richards

Gamification. We all know immediately upon reading the word that there’s something inside that hasn’t been figured out. It’s too broadly applied and holds very little real meaning.

The word itself seems to say, “look what this disruptive technology of the internet has done to us” – the second half of the word seems to offend the first half. The “you got marketing in my once-loved-behavior!” notion of the naysayers results in that icky feeling you get when you see how sausage is made. With the wonder and imagination that games represent for so many, the word falsely infers that one can simply go and pay someone to “gamify” something – and somehow that’s supposed to be a good thing? There’s conflict in gamification. We seek to understand it. Bring on the badges!

Yes. The business world sees the Farmville invites and Foursquare badges a-flyin’, and figures that gamifying their world means imitating the tactics readily surveyed by just being on Facebook. -5, friends. There’s more to it.

Rules for the Attention Economy

Here’s the truth. Game mechanics are the simple rules for the attention economy. If brands want consumer love and attention, they need to be prepared to live and die by the principles of game. Brands are quickly understanding that while traditional advertising (on any platform) sets or raises expectations, it is an increasing digital or interactive responsibility to pay off, prove, or deliver on those expectations or promises. In the world of a brand – this exchange is proving to not just affect perception, but other, very tangible results like churn, incremental purchase, and new sales from word of mouth. Yes, the increasingly digital world is where this gamification is a viking.

So, what is it about some brand-led games that make them so much more successful than others? What separates a Nike + from some pedestrian rewards-points offer? What was so magical about the McDonald’s Monopoly game? When it works, the game mechanics or brand narration can almost become invisible. When you are motivated to act, and the individual mechanics just become part of the game. When we’re doing it right, these principles are usually what you’re not seeing:

1. Loss Aversion: Prospect Theory, Risk, and Reward

Most people tend to prefer to avoid loss before they seek gains; it’s easier to motivate a person via pain avoidance than it is to motivate via pleasure-seeking. Zynga’s Farmville does this in several ways – first by creating a context of a starter farm and some fixed amount of currency.

Players must use the currency to plant and harvest crops, earning more in return. If you don’t visit the farm or care for your crops, then they wither and die. It’s not the value of the Zynga currency that motivates – it’s the potential loss of the crops (and thus, progress) that motivates. Similarly, brand participation in Foursquare rewards is tepid, at best. There’s no real value to being a mayor – but, once a mayor, maintaining that mayorship over co-workers, friends and complete strangers alike drives that obsessive check-in and mayoral maintenance behavior that joyously clutters our feeds today.

A creative farmscape from shelly30. Every last detail thematically arranged, right down to the row of red, green and white soldiers standing guard in front of the house with the candy cane fence. Featured at games.com.

Since these decision theories are only descriptive of human behavior, it’s not a formula for creating game-like behaviors – but, it does provide important rules for game-makers around how people feel about evaluating risk, potential reward, utility, and “anteing up” in a relationship. These principles are especially powerful when combined with other elements of game, like status, reputation, and feedback – all leading to trigger a motivation to act or interact.

2. A Pervasive Economy: Status, Reputation, Competition

Assessing our own value by comparing ourselves to others sometimes seems like more of a social woe than a valid and encouraged part of game design – but, without getting into the origins of competition and reptilian-brain urges, let’s just say that making achievements social encourages people to continually out-do, one-up, and stay motivated to reach clear goals – another necessary element of good gamification.

Call of Duty: Elite, the player community product for Activision’s blockbuster shooter franchise. It mixes your game data with your social graph, and helps you play together, better.

The first part of this principle starts with understanding the concept of status, reputation, and competition. Connecting players socially drives sustained engagement. A recent PSFK report highlighted a few products that use out-and-out peer pressure to motivate: a solar charger that tweets an individual’s level of “greenness,” Reebok’s Promise Keeper app that broadcasts runners’ intentions to exercise – and GPS – to hold them accountable, and a Japanese alarm clock app that embarrasses users via Twitter when they hit the snooze button.

Okite, an app recently featured in PSFK’s “Future of Gaming” report – a Twitter-connected alarm clock that sends out “a random, and usually embarrassing phrase to [the user’s] timeline.”

The Visible Economy

This draws into sharp focus the second part of this particular principle: a visible economy. Personally-relevant leaderboards, social competition, and status comparisons are a great way of communicating to people that there’s an economy at work; and points must be readily redeemable. Badges need to carry some shared symbolic value.

Developing an economy means clearly demonstrating the value exchanges and currencies – and ensuring that the playing population is large enough to assure players that they have a chance to exchange value – whether that value is monetary, or comprised entirely of smack-talk. It’s not to say that all game economies are driven solely by inter-frenemy competitions. They’re not. As the game master, there’s a responsibility to make sure that players have someone or something to exchange value with – whether that’s a population of non-player-characters and an exchange rate with their particular currency, reputation within a faction, or a player-and-game-controlled economy where items are valued by their rarity. (Yes, World of Warcraft probably holds enough examples to write a book). The game must produce currency that’s readily redeemable in the world (or virtual world) around the player. Otherwise, there’s no economy. No economy? No motivation.

3. Discovery: Surprise and Delight

While prospect theory focuses on how people make decisions based on what is known to them – weighing risk and reward, this element of game says more about progressive disclosure and story-based striptease. It’s a classic condition of storytelling: the narrator knows more than the listener, and that interplay of disclosure is a tension that keeps game players coming back again and again. In fact, on that point, this is a great opportunity to combine discovery another well-known game mechanic: periodic events. Players may return to redeem period-based regeneration or awards – and this provides a great opportunity to progressively disclose an unfolding plot, new areas of play, and additional features.

Story unfolds interactive games in Sesame Street’s “Monster at the End of This Book…” iPad app. The timeless children’s classic adventure with Grover now requires light game interactions to turn each page.

4. Hope: Feedback, Trigger, and Certainty

This principle is more tactical, more of a list of ingredients with a theme. People need to know what’s expected of them. Where’s the bar? What was the effect of my last action. It’s as much about real-time asynchronicity and providing clear feedback to players as it is about developing a communication mechanic that’s sustainable.

Game-like communications means establishing pace and certainty in an otherwise surprising dialogue. Seeing points accumulate as actions are taken establishes a clear and instant reward system. Programming communications on a certain period provides an opportunity to trigger motivation – even if we’re just providing a mundane update to the player. The player’s interplay and dialogue should probably always be a symphony of serial story, utility communications, and a connection back into the player community around her. This provides constant setting, clear feedback to the player and, thus, hope that the challenge is both valuable and reachable.

For instance, while the harrowing music that swelled when Zelda was reduced to 1 of 5 hearts clearly was designed to raise the pulse, the health system in that game helped communicate a sense of hope along with that excitement. There was hope in recovery, even if additional damage was taken enroute just heightened the urgency to go find some more hearts before continuing headlong into the unknown hedge around the corner. This kind of feedback is what makes humans better in games than they are in real life. Jane McGonigal mentions in her TED talk, “Gaming Can Make A Better World.” This kind of constant feedback plays a big part in enhancing human performance and capability.

The Legend of Zelda was all the epic story and adventure of Dungeon’s and Dragons, but interlaced with light puzzles and interactive action. As the game progressed, life (hearts) capacity grew, but so did severity of damage – along with difficulty of quests. By the way, here’s Zelda : )

5. Epicness: Story, Connection, Truth, and Meaning

To continue on the path set forth by Ms. McGonigal, the principles of game and decision theory share a sizable overlap with positive psychology – the study of happiness. When we are engaged in play, our learning centers are activated, our performance is enhanced, and we have fun.

Why do we play? Because we have hope that we can overcome the challenge. In fact, maybe that’s the allure of a game world vs. solving problems in the real world: we know that the problems were designed by man, and can be solved. We connect to the stories of game as far as they conform to the arcs and structures that parallel the human experience so vividly – a structure well-documented in Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey construct.

Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey – or the 17 stages of the Monomyth: A story pattern observed in human narrative, in various cultures and across centuries of recorded storytelling and myth. Campbell described the pattern in his book, “The Hero with a Thousand Faces.” This graphic was posted on the popular blog by Eric Fernandez (@royalsocietyap), “The Royal Society of Account Planning”.

The rules of game, here, are clear. Players must see themselves in the challenge. Lighting up competitive centers in the brain requires the game to communicate meaning and status: provide feedback, present triggers, progressively disclose the plot, and illustrate the economy. In all of this, there must be a meaning – story must be at the core. Casual or hardcore, there must be some human truth and drama, played out interactively. Heavy, epic stories of adventure create meaning beyond impulse, while light and casual interactions can use simple rhythm and humor to tease out a response from the player.

People evaluate communication via storytelling models like The Hero’s Journey, perhaps searching for a truth between the story and their own lives and experience. This is the next frontier, it would seem: To connect the ever-growing world of game-players to real-world challenges – not just the challenges in alternative realities. Both the PSFK “Future of Gaming” report and Jane McMonigal’s body of work point to a future where people use game constructs to solve real world problems like hunger, poverty, obesity – taking a smiley-face approach to a bunch of very frowny-face challenges. Will it work? Probably – but, scale depends on whether those real-world challenges conform to the mechanics of fun.

Why do we play? Perhaps Italo Calvino said it best: “The search for lightness is a reaction to the weight of living.”

One thing is for sure. We are wired to compete and play. Maslow provided a popular model for understanding motivators behind many of our behaviors – and truth is, there’s still competition at every level of that model. Our innate drive to self-preserve and thrive makes competition and play something that we’re all programmed to do, whether we realize it or not.

What’s Nike +? Competitive, Physical Self-Actualization. Right?

Facebook? Not just community…competitive happiness, competitive comedy, domestic one-upsmanship, and competitive travel photo documentary adventure.

So, how many “likes” do your last vacation photos have? Are you winning at Facebook? (Source: Branding Magazine)

上一篇:论述确立独特游戏美术风格的重要性