解析对玩家产生作用的5种吸引力类型

作者:Jason Tocci

我曾经见过弟弟们尝试在游戏中驾驶SUV飞下悬崖。这是许多年前的事情,那时《侠盗猎车手3》还算是新游戏,但已经可以很容易从网络上找到让汽车飞行的作弊码。在将近1个小时的时间里,他尝试让汽车滑过河面冲入足球场。最终,他们穿过足球场的墙面,成功让汽车停在球场中,发现场上的粉丝们正在叫喊某个球队的名字。

当我阅读各种有关为何我们认为游戏“有趣”的理论时,时常会回想起这件事。有些最流行的参与度理论认为,游戏需要提供优化级别的挑战,包含令人愉快的“流程”。诚然,这些东西能够增添游戏的趣味性,但是游戏的趣味性还涉及到其他的内容,例如有意打乱物理规则带来的兴奋感,以及最终产生的黑色幽默。

同时,通用于各种不同类型玩家的理论可以用来探究游戏对我们产生的影响,但其中的内容绝非挑战性这么简单。

但是,这些理论在尝试简化和代码化玩家想法的过程中,在探究游戏如何以不同方式或在不同背景下产生影响,以及如何处理与精心构建的模型不相符的游戏吸引力时遇到了许多问题。

我在本文陈述了5种吸引力类别,描述我们参与到游戏中的不同方式(游戏邦注:有些方式可能包含多种吸引力类别)。

这个吸引力框架形成于2008至2011年间开展的研究,包括网络资源的分析(游戏邦注:比如从公共论坛讨论和博客评论中收集资源)和实验研究(比如在街机店中同他人一起玩游戏)。

我将在下文中提供的吸引力不一定都是“优秀”的吸引力,这个框架中包含受部分设计师批评的吸引方法,但是它们可以让你明白哪些内容可以让游戏显得有趣,以及如何融合不同种类的吸引力来鼓励甚至阻止不同种类的参与度。

玩家和吸引力类型

我有意从游戏和玩法特征的角度来描述这个理论,而不是玩家自身的特征。无论你讨论的是区别“休闲”和“硬核”的常识还是利用社交心理学的更科学化的方法,玩家个性模型和人口统计学都因其简单性而极具吸引力。

尽管如此,从玩游戏的角度来描述参与度似乎更加有效,主要原因有3点。

第一,“玩家类型”理论往往无法同人们玩游戏的真正实验性和见闻性证据相匹配。我们在不同的游戏中会呈现出不同的“个性”,甚至在提供各种不同机制的同一个游戏中也会如此。

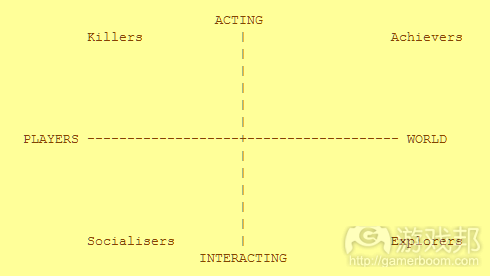

比如,以本文开头的故事为例,我的弟弟们不断地驾驶汽车从悬崖飞下。那么,根据Bartle的玩家分类,他们属于何种玩家类型呢?

算是不断探索游戏系统和故事世界的探索者吗?他们试图进入游戏内的足球场,想知道游戏逻辑是否允许他这么做,他们想要知道足球场中究竟有什么。

他们努力打破基于规则的挑战,算是成就者吗?这是个他们自己设立的挑战,但是仍然有完成的条件,最终发现的内容也可以被视为奖励。

他们会同其他人一起玩游戏,共同探索游戏中的故事,这样算是社交者吗?诚然,合作体验游戏并分享笑点也能够算是游戏的吸引力。

他们试图颠覆游戏的规则,算是杀戮者吗?如果他们没有使用作弊码的话,就不能以这种方法来体验游戏。

如果我们发现,在其他情况下他们会独自玩游戏,遵从游戏规则并将注意力集中在故事情节上,那么这是否会改变我们的上述论断?或者,如果我们发现他们以完全不同的方式来体验其他游戏,比如在竞争性运动游戏中回避所有“作弊”或探索作法,那么是否也会改变我们的论断?

坦诚地说,Bartle的这个模型原本就不是用来描述所有的游戏玩家,而是用来描述MUD玩家。他甚至还强调,有3种玩家完全没有将MUD视为“游戏”,而是将其视为“消遣之物”、“运动”和“娱乐”。他承认,多数玩家多少都会涉及到四种类型的特点,但总体上会更偏向于某种特定类型。

所以,我的目标是专注于小群体玩家或单个题材来揭示问题。玩家在不同的游戏或不同的社交背景下会展示出不同的个性和行为,所以不能以个性和内在的“类型”来作为愉悦的根源。我的弟弟们以特定的方式来玩游戏,不只是因为他们属于何种玩家,当时的情境背景也很重要:所有人都是同自己熟识的其他玩家分享游戏,而且他们在玩的是一款允许他们采取不同玩法的游戏。

这种想法给我带来了第二个问题,基于玩家类型而不是行为类型来描述我们如何参与到游戏中。围绕玩家类型来设计游戏,玩家类型的不确定性便是我们面临的风险。

这种风险造成的危害可能同我们错失部分我们不知道其存在的玩家一样无足轻重,有些玩家不能被简单地划归“硬核”或“休闲”,也不能被定为是杀戮者、成就者、探索者或社交者。但是,由此带来的更大问题是,带着区分玩家类型的想法来设计游戏,可能会落入“强迫”玩家体验某种游戏的俗套。

在Bartle的原文中,他对“杀戮者”的描述并不恰当。他认为,从根本上说,杀戮者是种无法与他人和谐相处的玩家类型。Bart Stewart的综合模型将这类玩家的行为视为多数游戏不愿考虑的玩法类型,但是事实在于,原本的分类方法确实将这类玩家魔鬼化。同时,《战争机器》之类游戏的发布表明,鼓励“杀戮者”玩法的游戏的确存在一定的市场,此类游戏提供了各种击败对手的残忍方法。

但是,错失用户带来的更大问题是,因为假设某种游戏只适合于某种玩家“类型”,所以在无意间便忽视了其他类型的玩家。这种风险可能在公开分类中比较少见,通常是将玩家类型与游戏类型直接联系起来,比如我们习惯假设女性更有可能是“休闲”玩家,对快节奏的第一人称射击游戏不感兴趣。

坦诚地说,有些研究确实在不同的玩家类型中观察到不同的特征,有些人也曾试图解释这种差异,比如男性和女性间天生的认知偏差。但是,重点还是要考虑到,情境在玩家感觉中所占的位置。或许换个环境和背景,这些玩家就不愿意尝试游戏。

比如,Diane Carr的研究发现,当女孩们有机会频繁在舒适和无审判的气氛下玩任何她们想要体验的游戏,那么老式和实验性证据的经验都会失效。确实,男性对第一人称射击中的导航确实较为熟悉,但是这或许并非许多女性不玩此类游戏的主要原因。事实上,游戏更适合某些玩家,这可以作为考虑谁会选择玩游戏的因素,而不是判断哪类玩家能够从中感受到乐趣。

但是,从设计更具参与度的游戏这一出发点来看,我觉得考虑“游戏吸引力”的最重要原因在于,可以更容易地思考如何融合不同的吸引力而不是个性。通过设计,我们可以使采用不同玩法的用户均能从游戏中获得乐趣。或者,我们也可以有意削减游戏提供的吸引力数量,这样它们才不会发生冲突。但是,在我开始提供如何思考的方式和范例时,我想要先阐述个人认为有用的吸引力类别。

5种吸引力类型

近些年来,流行游戏并没有专注于挑战性,出现了更多能够引人思考而不是单纯提供娱乐的“严肃”游戏,所以此刻似乎是时代将行业注意力吸引到更宽广概念上。

当然,我也会遵循学术传统,借鉴我最喜欢的理论来组成自己的理论。Bart Stewart的统一模型在识别某些玩家行为上似乎很有用,呈现具体化的玩法风格,可以指导游戏的设计。“悲伤”不只是种情绪,也可以构建到游戏中来吸引某些需求和兴趣。

Mitch Krpata的《New Taxonomy of Gamers》区分了不同种类的挑战、沉浸度和娱乐。Michael Abbott的《Fun Factor Catalog》提供了一套基于数据得出的吸引力,但是目前还未被严密和系统化地组织起来(游戏邦注:仍处在总结过程中)。

同时,Hunicke、LeBlanc和Zubek的MDA(Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics)框架提供的可能是最容易理解的系列方法,让玩家参与到游戏中,但是对某些层面的探索略显不足。少数理论化方法甚至将“屈服”当成人们玩游戏的原因。

综合上述内容,我总结出的5种游戏吸引力类型为:

1、成就:涉及外在和内在奖励的吸引力。

2、想象:涉及伪装和故事讲述的吸引力。

3、社交:涉及友好社交互动的吸引力。

4、娱乐:用于调整身体、精神或情感状态的吸引力。

5、颠覆:涉及打破社交或技术规则的吸引力。

尽管我自己的研究主要专注于电子游戏,但是我注意到以上许多吸引力类型同样可以用于分析其他类别游戏的设计。对于每种类型,我都阐述了几种属于该类型的吸引力,但它们并非是其类型所包含的全部内容。

成就

成就指来源于“胜利”或在游戏中所获成功的奖励感。相关吸引力包括完成(完成游戏,获得所有的奖杯、成就和解锁内容)、完善(玩游戏的技能获得提升)、统治(成为所有玩家中的最强者)、财富(通过努力获得奖励)和建设(使用游戏来创造艺术或对象)。

这里,我从Mitch Krpata的说法处获得灵感,区分了完成和完善。在我自己的调查中,完成是激发玩家赚取《光晕3》中每项成就的吸引力,但激发他们尽量提升多人游戏排名的则是完善。统治也是后者中的一个因素,但是玩家打败其他玩家时总是会产生满足感,即便玩家并没有提升自己的技能(游戏邦注:比如骨灰级玩家有时以碾压差劲的对手为乐)。

但是,必须注意到的是,完成并不一定只包含通过个人技能来精通游戏,还包含在游戏中获得胜利。玩家在玩赌博机时看到3个草莓连成一线或及时收获他们在《FarmVille》中的所有作物时也同样觉得有趣,即便这个“胜利”过程并不涉及到任何技能。这也正是我添加了财富这种吸引力的原因,它代表无需任何能力甚至不用付出任何精力而产生的完成感。

描述完所有这些吸引力后,或许你会觉得“建设”的存在很古怪。但是,我将其划归这个类型的原因在于,游戏中的创造性行为都是面向目标的,往往伴随着成功或失败的外部指示器。

无论最终结果是用《FarmVille》中的农作物拼出《蒙娜丽莎》的造型、一个极具吸引力的《上古卷轴:天际》角色还是《Minecraft》中精心构建的城堡,建设呈现的是用户自定义的“完成”,游戏只是实现这种完成的平台。

想象

想象指伪装的做法,特指故事讲述和模拟。相关吸引力包括旁观者(“观看”故事)、管理者(“制造”故事)、角色扮演(假装自己是另一种身份)和探索(假装存在于虚拟环境中)。

不同的游戏所强调想象吸引力的类别和程度有所不同。比如,《上古卷轴:天际》特别强调管理者和探索。查看网络上的《天际》论坛,你会发现有大量玩家分享他们的冒险故事和意料之外的事情,每个人的故事都存在不同之处。游戏中有角色扮演的空间,许多玩家为自己的角色生成故事和额外的背景,但是游戏本身并没有让玩家这么做,至少没有直接引导玩家这样体验游戏。

相比之下,《质量效应》提供的探索就比较少,游戏中呈现的是线性化的探索路径,但游戏更侧重于直接引导玩家进入角色扮演,而且内容更专注于旁观者,通过电影化的过场动画和主角明确的个性来呈现。玩家仍然带有管理者的感觉,他们会在论坛上讨论自己如何做出不同的决定并讲述不同的故事,但是叙事的范围相比《天际》显得较为狭窄,因为游戏更多地整合好莱坞的叙事技术。《战争机器》的战役模式未提供管理者玩法,但是通过对话、过场动画和音乐,游戏仍然提供了让玩家扮演旁观者的机会。

我还认为,旁观者不仅包括玩家参与到正在玩的游戏的故事中,还包括在观看其他人玩游戏时参与到故事中。虽然“胜利”在玩家享受游戏的乐趣中扮演着重要角色,但游戏的故事和进程同样具有非凡的吸引力。

社交

社交指玩家使用游戏来与其他人联系的各种方法。相关吸引力包括对话(在游戏中通过游戏聊天系统实现,或通过游戏内置消息系统实现)、协作(在游戏期间支持和帮助他人)和慷慨(单方向的帮助性行为,比如赠送礼物或帮助低等级玩家更快升级)。

当然,你或许会辩解称,社交是任何娱乐媒介的吸引力,从与好友讨论最喜欢的书籍到与许多人讨论电影都是如此。但是,游戏往往通过特别的设计来鼓励这种玩家间的社交行为。

比如,《Rock Band》在多人游戏时比较有趣,原因不只是在于参与人数较多,还因为它体现出协作感:玩家依靠他人,也能够帮助他人。如果有个玩家表现很不好,所有人的歌曲都会结束,所以其他玩家必须注意,通过触发“加速传动”模式来挽救那些落后的队友。

许多基于团队合作的动作游戏都仰赖于队友间的对话,玩家之间不只谈论每天的生活(游戏邦注:虽然有些玩家会借助游戏作为与他人探讨日常生活的工具),而且还会分享战术信息,规划对抗对手的方式。

但是,单向慷慨机制并没有被正式挖掘出来。这似乎听起来有点矛盾,如果你设计出的系统能够识别到帮助他人的玩家,那么难道不应当奖励这个慈善的玩家?将这样的系统描述为协作不是更为合适吗?我想要说的是,在游戏中帮助他人不一定都会获得回报,而这样的系统依然能够让玩家感到满意。

比如,《FarmVille》允许玩家免费向他人赠送礼物。玩家可以要求对方回赠(游戏邦注:许多玩家往往也这么做),但是有些玩家喜欢使用这个功能,仅仅是因为他们喜欢向他人赠送礼品。

不幸的是,这样的系统被开发商视为营销工具而不是吸引力,结果玩家的好友经常会收到不想看到的Facebook信息,通知他们好友向其赠送“礼品”。有些MMORPG还提供正式化的“导师系统”(例如《Shadow Cities》或《最终幻想11》),这表明确实这种吸引力确实存在发展空间。

娱乐

娱乐指怡情和消遣的时间,通常指使用游戏来调节人的心理或心理状态。相关吸引力包括情绪管理(面向放松、高兴、乐趣或其他情绪)、压抑(积极避免思考令人痛苦或困难的事情)、沉思(考虑发人深思的问题)和努力(通过玩游戏来充实体能)。

这些吸引力中,覆盖面最广的是情绪管理。我将此作为单独一种吸引力,而非针对每种吸引力(放松、娱乐、活跃等)分别提出一种情绪管理方式,不仅仅是因为扩展开来的话会更冗长,而是为了明确区分基于玩法行为的吸引力及其产生的情感状态。

也就是说,值得注意的是,情绪管理包含更多种的状态,不只有“感受到乐趣”。《flow》是款节奏缓慢且令人镇静的游戏,专门用来展示游戏可以鼓励人们放松,并非只会让玩家兴高采烈。《旺达与巨像》和《最终幻想7》有时受人褒奖的原因在于游戏会让玩家产生悲伤的情感。玩家根据一定的背景来选择不同的游戏,比如游戏的开发公司和玩家希望从游戏中获得的情感。

沉思也是种相关吸引力,甚至可能是情绪管理的一部分。比如,《Passage》就是款带有精妙内涵而非明显“趣味性”目标的短游戏。这款游戏的目标是让你思考,而不是让你体验乐趣。压抑是另一种相关吸引力,听起来似乎没什么价值,因为它的作用是让玩家去克制自己无谓的想法(游戏邦注:比如赌博上瘾)。但是,正是因为有这种吸引力,游戏成为医院中使用的重要工具,用非药物的形式减轻病人的痛苦。

我认为需要将娱乐作为独立类型的主要原因在于,它包含让许多所谓的“休闲”游戏获得成功的主要吸引力,包括Facebook和手机“社交游戏”和Wii及其他系统上的肢体控制游戏。无论评论家或设计师有何看法,《FarmVille》和《Tiny Tower》等非技能游戏的成功都表明,这些游戏提供了玩家需要的东西。

所以,我们应当认识到玩家的确从这些游戏中获得了所需的东西,这样玩家才愿意体验这些游戏。尽管许多传统玩家批判Wii游戏并没有充分发挥体感技术的优势,但是该系统的销售势头依然不减。即便是那些最简单的Wii游戏,也让玩家在客厅中获得娱乐和放松。

颠覆

颠覆指与社会或游戏逻辑所定义的常态和期望相反的行为。相关吸引力包括挑衅(通过“不恰当”行为主动成为其他玩家的对手)、破坏(打破游戏逻辑)和违犯(做出“邪恶的”行为,比如杀害友好的NPC)。

我提出的这3种吸引力都涉及到打破某种规则。“挑衅”显然打破的是游戏中众玩家和睦相处和礼貌互动的社交规则。“破坏”打破的是游戏代码所制定的规则,如果你利用这种规则打破在多人游戏中获得优势地位,那么也算是打破“公平”游戏的社交规则。

“违犯”往往被视为是这三者中攻击性最小的,它打破的只是广义的文化准则,这种行为往往被其他玩家和游戏规则所默许。然而,我将这种违犯与其他颠覆吸引力相并列,是因为这种行为背后的趣味来源也是“成为恶棍”。以上这些行为的基本吸引力都是做某些被认为不应当做的事情。

我将此视为有效的吸引力,并没有把它们当成玩家的作弊和不当行为,因为乐衷于做这些事情的玩家如此之多,所以已经不能将其视为异常的行为。那么,设计师要如何对待这种吸引力呢?

当然,最显而易见的答案就是,完全保持中立。设计师怎么能够鼓励玩家打破规则或者让玩家从打破规则中寻找兴奋点呢?但是,现实情况不一定要如此。设计“邪恶”玩法也是提供吸引力的一种方法:比如,在《辐射3》中,玩家通过与凶手共进晚餐或将小孩卖给奴隶贩来打破非游戏逻辑规则,但是仍然可以选择符合叙事期望和社交常态的传统玩法。

设计师甚至还可以将挑衅的内容融入游戏中,之前提到的《机器战争》中玩家间的暴力和挑衅正是此例。这些游戏都向玩家提供了打破普通社交规则的方法,但游戏本身的规则并不受到破坏。

坦诚地说,既要鼓励玩家打破游戏规则,又不想冒游戏整体受到破坏的风险(游戏邦注:至少多人游戏部分不受到影响),这的确是件很困难的事情。作弊码等现象呈现了一种受批准的颠覆,在可控范围内打破游戏规则。

我们能否想象出一款有意鼓励玩家颠覆游戏规则的游戏?玩家尝试各种打破规则的方法,确实让游戏有受破坏的风险,但是有些开发者依然尝试使用这种吸引力。现在,“颠覆”或许是最未被开发者重视和探索的吸引力类型。

吸引力间的互补和冲突

看过这些吸引力后,你或许会注意到,它们并没有完全相互排斥。事实上,这才是重点所在。这使我们可以讨论各个交叉点的好处和坏处,以及如何设计游戏来利用这些交叉点。

比如,寻找和挖掘游戏的过失,提供了一种打破规则的“颠覆”吸引力,但是它或许也能够提供“完成”吸引力,比如揭示游戏系统中的秘密。《劲舞革命》提供“完成”吸引力,玩家在高难度歌曲中努力获得高分,在于其他玩家一起跳舞时能够感受到社交吸引力,游戏同时还通过让玩家移动肢体来感受娱乐吸引力。

有时,不同游戏吸引力对应不同的游戏机制,但是两者间并非一一对应关系。游戏可以提供与“完成”吸引力完全分离的“想象”吸引力,通过呈现感觉完全与玩家输入无关的叙事过场动画来实现,但游戏也可以通过对话互动来融合想象和完成吸引力,甚至呈现挑战成分。

比如,《质量效应2》中的对话场景提供了管理者吸引力,允许玩家选择如何回应,但是这其间缺乏“完善”玩家技能的吸引力。有些回应客观上比其他回应更好,但是最好的回应会用显眼的颜色标出,只要你保持在游戏中选择“友善”或“恶意”的回应,都能够取得最优的结果。

相比之下,《黑色洛城》和《杀出重围3:人类革命》等游戏中的对话场景拥有额外的挑战层面,要求玩家根据角色的面部表情和肢体语言来选择最有效的回应。

当然,预想不同吸引力之间的冲突同融合吸引力同等重要。这使设计师可以区分功能的先后次序,或者为功能提供额外的背景,其基础就是设计师最想要引入的吸引力。比如,我曾经在Eludamos的一篇文章中描述过,“死亡”在游戏中往往是令人不悦的故事情节,但是可以通过某些恰当的方法让玩家感觉到他们的行为可能导致失败和死亡。

换句话说,以牺牲“想象”吸引力为前提来获得传统意义上的“完成”吸引力。但是,有些游戏的确预想到了吸引力间的冲突,并试图做出挽救和补偿,比如通过叙事方式绕过死亡的威胁:《生化奇兵》中会以克隆体的形式复活。或者将死亡作为可以挽回的失误,比如《波斯王子:时之沙》中的做法。

最戏剧性的方法是完全去除某些功能,确保你最想要鼓励的吸引力显得最为突出。比如,考虑下游戏设计师需要如何处理想象吸引力和社交吸引力之间的潜在冲突。《无主之地》或《战争机器》中的协作性多人战役提供了与好友开展社交的机会,甚至还有助于让挑战变得更具趣味性,但这些吸引力的存在可能需要牺牲想象,因为你和好友可以直接在游戏中交谈。

《恶魔之魂》也有着协作性和竞争性多人游戏机制,但是它优先呈现想象吸引力(游戏邦注:比如营造紧张的气氛),将其置于社交吸引力之上(比如同好友交谈)。你无法直接使用语音聊天系统与其他玩家交谈,但是可以通过短消息来间接交流。通过强迫性地将玩家分割在自己的世界中,使游戏显得风格迥异。

虽然有时候吸引力间的冲突及其原因并不明显,但根据这种方法来描述游戏功能至少能够知道现有游戏中功能是否会起作用。我希望,这种方法可以使行业将来出现更多富有创新性和探索性的有趣游戏。

结论

这种游戏吸引力理论只是试图涵盖所有类型的游戏。也就是说,我并没有将此作为通用法则,这只是思考游戏潜在价值的起点而已。

此外,我还看到了更多其他吸引力存在的空间。无需技巧的“社交游戏”是否含有更为复杂的方法,而不仅仅是我描述的只含有娱乐和完成吸引力?Wii和Kinece体感游戏或运动类游戏是否应当独立于娱乐,自成一体?我自己还会继续探索这些问题,而且我希望其他人也能够提供建议。

但是,除了理论解析游戏吸引力之外,我还希望以上的讨论能够引导我们设计出更多种类的有想法和创新的游戏。当设计师和开发者将游戏定位为主要目标是提供“趣味性”的产品时,便自然忽视了参与度和体验成分。当我们将玩家描述为只接受与自己玩法相符的游戏时,我们不仅忽视了可以从多种层面上触发和取悦玩家的问题,而且还有失去部分玩家的危险。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Five Ways Games Appeal to Players

Jason Tocci

I once happened upon my brothers attempting to fly an SUV off a cliff. This was years ago, when Grand Theft Auto III was still new, but it was already easy enough to search online for the cheat code to make cars fly. After about an hour of trying to glide across a river and into a football stadium, they finally cleared the edge of the wall, landed the car inside, and broke into proud laughter upon discovering the Easter egg inside: an image of fans spelling out the name of Liberty City’s football team: “COCKS”.

I often think back on this when I read various theories on why we find games “fun.” Some of the most popular theories of engagement come down to offering an optimal level of challenge, establishing a pleasant “flow” state. Surely there was something like that going on here, but there was also so much more, from the thrill of intentionally messing with the laws of physics to the naughty humor in the final payoff.

Theories that account for a range of different types of players, meanwhile, have been useful in considering that games affect us on more levels than simply how challenging they are.

In the process of trying to simplify and codify how people think, however, these theories have trouble accounting for how a game can affect a person in different ways and in different contexts, or how to address appeals of games that don’t fit quite as neatly into a carefully-structured model.

In this article, then, I offer five general categories of appeal (hence, “appeals”) describing a host of different — but not necessarily mutually exclusive — ways that we engage with games.

This framework of appeals has been developed through research conducted between 2008 and 2011, including discourse analysis of online sources (e.g., collecting examples from public forum discussions and blog comments; see “‘You are dead. Continue?’”) and participant-observation ethnographic research (e.g., playing games with people in arcades; see “Arcadian Rhythms”).

The appeals I’ll offer aren’t necessarily all “good” appeals — this framework includes ways that games engage players that some designers have criticized as little more than manipulation — but they may offer some broad ways to describe what makes games tick, and how to blend different kinds of appeals to encourage or even discourage different kinds of engagement.

Types of Players vs. Types of Appeals

I describe this theory quite purposely in terms of the characteristics of games and play instead of the characteristics of players themselves. Models of player personality and demographics are very attractive in their elegant simplicity, whether you’re talking about the common-knowledge distinction between “casual” and “hardcore” or more scientific approaches drawing on social psychology. (See Bart Stewart’s relatively recent Gamasutra feature for one such robust approach.)

Nevertheless, it may be more productive to describe engagement with games according to a variety of approaches to play itself, for at least three major reasons.

First, theories of “player types” often don’t easily match up with empirical and anecdotal evidence of how people actually play games. We can display different “personalities” between different games, or even within a single game that offers a variety of different mechanics.

Take, for instance, the anecdote that began this article, in which my brothers continually flew a car off a cliff. What type of players are my brothers in this example — say, in terms of Bartle’s types?

Are they explorers, fiddling with the game systems and investigating its world? A large part of the reason they were attempting to get into that stadium was indeed that they wanted to know whether the game logic would allow them, and they wanted to discover whatever might be inside.

Are they achievers, looking to beat a rules-based challenge? It was a challenge of their own making, but they still had a distinct end condition, and even a sort of in-game reward in the Easter egg.

Are they socializers, playing side by side, telling a story together through their play? Certainly, playing cooperatively and sharing a laugh had something to do with the appeal.

Are they killers, going out of their way to subvert the rules of the game? They couldn’t have played this way at all if it weren’t for the fact that they entered a cheat code.

Does it change our answer if we find out that they also played the game separately from one another on other occasions, each following the rules and paying attention to the plot? Or does it change our answer if we find out that they approach other games completely differently — say, eschewing any “cheating” or exploration in competitive sports games?

To be fair, Bartle originally suggested this typology not to describe all game players, but to describe MUD players. He even makes the point that three kinds of players aren’t treating the MUD as a “game” at all, but as “pastime,” “sport,” and “entertainment,” and acknowledges that “most players leaned at least a little to all four [types], but tended to have some particular overall preference.”

The fact that game critics and designers have applied this typology more broadly may reflect an admirably progressive willingness to broaden our understanding of what a “game” can be, but it also extends this particular model well beyond the claims of the original 30-person study that brought it about.

My goal with this thought exercise, then, is to illustrate the problem with focusing on a small group of players or a single genre. Players exhibit different preferences and behaviors with different games or in different social contexts, which makes it problematic to claim that anything so fixed as personality or an inherent “type” is at the root of enjoyment. My brothers played the way they did not just because of who they were, but because of the context of the situation: Each was sharing the game with another player he knew very well, and they were playing a game whose design allowed them to play it in multiple ways.

This brings me to the second major issue with describing how we engage with games based on types of players instead of types of behaviors. By suggesting that we design games around categories of players, we run the risk of reifying our own top-down notions of what the player base is like.

This risk could be as innocuous as simply missing out on audiences that we didn’t know existed — a segment of players that requires more nuance to understand than “hardcore” or “casual,” perhaps, or that can’t be defined as any of killers, achievers, explorers, or socializers. More problematic, however, designing games with player typologies in mind opens the doorway to reinforce stereotypes of which games different people “should” be playing, and which play styles are more valid than others.

In his original article, Bartle didn’t have much good to say about the “killers”; they were basically the Slytherin of player types, a category for those who don’t play well with others. Bart Stewart’s Unified Model goes some way toward legitimizing their activities as a valid play style that most games simply aren’t designed to accommodate, but the fact remains that the original typology was constructed in such a way that essentially demonizes a segment of players. In the meantime, releases like Gears of War have demonstrated that there’s a market for games that explicitly encourage “killer” play styles, such as by offering brutal and demoralizing ways to dispatch with opponents.

Even more problematic than missing out on audiences, however, is to unintentionally exclude audiences by assuming that certain games are only for certain “types” of players. This risk is probably less in overt categorizations than in implicit or easily inferred connections, like the common assumption that women are more likely to be “casual” gamers, and less interested in games like fast-paced, first person shooters.

To be fair, some studies have indeed observed different preferences between different demographics, and some have even attempted to explain such differences — say, in terms of innate, cognitive differences between men and women (e.g., see John Sherry’s “Flow and Media Enjoyment” [pdf link]). Again, however, it’s important to consider the huge role that context can play in terms of what people will feel comfortable engaging in — or, to put it another way, what they’ll even bother to try.

Consider a study by Diane Carr, for instance, which found that when girls were given the chance to regularly play whatever games they wanted in a comfortable, non-judgmental atmosphere, expectations from both stereotypes and other empirical evidence practically disappeared. Yes, men might have a slight neuropsychological edge at navigating a 3D maze in a first person shooter, but that’s probably not what’s keeping more women from playing. The fact that a game is popularly considered more “meant for” some audiences than others is worth considering as a factor in who chooses to play, rather than who would be capable of enjoying it.

From the standpoint of simply designing more engaging games, however, the greatest reason I see for thinking in terms of “game appeals” is that it’s a lot easier to contemplate how to blend different appeals than different personalities. Through design, we can make room for a number of different ways to enjoy a game, or we can purposefully pare down the number of appeals a game offers so that they don’t conflict with one another in unintentional ways. Before I offer some more specific examples of how to think about this, however, I’d like to suggest what I see as some useful categories to think about appeals.

Five Categories of Appeals

Researchers, critics, and designers have suggested a lot of ways to analyze the ways that games can engage players. Why throw in one more? Partly, I offer this approach to validate some excellent ideas suggested by others, backed up with additional research. In addition, however, I offer this approach to fill some gaps that may not be discussed on a widespread level yet. And finally, so much of the research and theory on how we engage with games either focuses very specifically on challenge, or defines engagement with games in terms of “fun”.

Given that recent years have seen an explosion in popular games that are not at all challenging, and a quieter expansion in “serious” games that provoke thought more than provide amusement, it seems a good time to draw attention to broader concepts of how we play.

I do, of course, intend to follow the grand academic tradition of borrowing wholeheartedly from my favorite theories. Bart Stewart’s Unified Model is especially useful in recognizing that certain player behaviors represent legitimate styles of play that designs can purposely accommodate; “griefing” isn’t necessarily just for jerks, but something that can be built into a game to appeal to certain needs and interests.

Mitch Krpata’s New Taxonomy of Gamers offers some usefully fine-tuned distinctions between different kinds of challenge, immersion, and recreation. Michael Abbott’s Fun Factor Catalog offers a data-based set of appeals, but without much rigorous, systematic organization to date (as it is still a work in progress).

Hunicke, LeBlanc, and Zubek’s MDA [pdf link] (Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics) approach, meanwhile, offers perhaps the most comprehensive range of ways that players engage with games, but leaves some aspects relatively unexplored. Few theoretical approaches even recognize “submission” as a reason people play games — so what does it look like?

Consider here, then, five categories of game appeals:

Accomplishment: Appeals involving extrinsic and intrinsic rewards.

Imagination: Appeals involving pretending and storytelling.

Socialization: Appeals involving friendly social interaction.

Recreation: Appeals for adjusting physical, mental, or emotional state.

Subversion: Appeals involving breaking social or technical rules.

Though my own research has focused primarily on video games, I’ve noticed that many of these appeals may be equally effectively applied to analysis of how other sorts of games are designed, as well. I’ll suggest a few specific appeals for each category, but there is likely room for more.

Accomplishment

Accomplishment refers to the rewarding feelings that come from “winning” or otherwise succeeding at a game. Related appeals include completion (finishing a game, getting all the trophies/achievements/unlockable content), perfection (improving one’s skills at the game), domination (besting other players), fortune (earning a reward through chance), and construction (using a game to create art or objects).

I take a cue from Mitch Krpata here in making a distinction between completion and perfection. As I found in my own research, completion is what inspires players to earn every Achievement in Halo 3, but perfection is what inspires them to achieve the highest multiplayer ranking possible. Domination is also a factor in the latter, but a player can find satisfaction in defeating other players even if she isn’t necessarily improving her skills (as even expert players sometimes take pleasure in crushing poorly matched opponents).

Note, however, that accomplishment doesn’t necessarily only include mastering a game through one’s own skill, but simply winning at it. Players still find something appealing in lining up three cherries on a casino slot machine, or harvesting all their crops on time in FarmVille, even if there was no actual skill involved in the “win”. This is why I add an additional appeal for fortune, representing a sense of accomplishment through no actual ability, or perhaps even any effort.

After describing all of these appeals, it may seem odd to group construction — an expressive act — alongside more traditional concepts of “winning.” I include this here, however, because acts of creativity in games are similarly goal-oriented, and often accompanied by external indicators of success or failure (such as appreciative comments by forum-goers looking upon your screen shots).

Whether the end result is a mosaic of the Mona Lisa rendered in FarmVille crops, an especially attractive Skyrim character, or an exquisitely-constructed palace in Minecraft, construction offers a sense of user-definable accomplishment all its own; what the game contributes is a platform that makes this possible.

Imagination

Imagination refers to practices of pretend, with particular regard to storytelling and simulation. Related appeals include spectatorship (“watching” stories), directorship (“making” stories), roleplaying (pretending to take on another kind of identity), and exploration (pretending to exist within a pretend landscape).

Different games emphasize different imagination appeals to varying extents. Skyrim, for instance, has a heavy emphasis on directorship and exploration. Go on any Skyrim forum online, and you’ll find plenty of players sharing detailed stories of their adventures and the unexpected things they encountered, each different from the others. There’s room for roleplaying — many players generate quite a bit of back story and additional context for their characters — but the game itself doesn’t really ask players to do this, at least not directly.

In contrast, Mass Effect offers less in the way of exploration, giving players a more linear path to explore, but it more directly guides roleplaying and focuses more on spectatorship, with cinematic cutscenes and clearly defined personality options for the protagonist. Players still have a sense of directorship, discussing on their own forums how they made different choices and told different stories, but the range of narratives is narrower because the game is written to more resemble Hollywood storytelling techniques. Gears of War, meanwhile, offers no opportunity for directorship in its campaign mode, but through dialog, cutscenes, and music, still offers opportunities for spectatorship.

I also humbly posit that spectatorship should include not just engaging with the story of a game you’re playing, but engaging with the story of a game you’re watching someone else play. This refers not only to players I’ve spoken with in the course of my research who make their spouses buy certain games so they can watch somebody else play through for the story, but also to the many thousands of spectators of professional sports at stadiums and in front of televisions. Though “winning” plays a part in people’s enjoyment of such games, the unfolding drama of a game in progress, with an uncertain end, can appeal to both players and spectators alike.

Socialization

Socialization refers to the various ways that players use games to connect with one another on an interpersonal level. Related appeals include conversation (through game chat during play, or made possible through in-game messaging), cooperation (supporting and helping one another during play), and generosity (helpful behavior in a more one-way direction, like giving gifts or helping a low-level player advance more quickly).

You could, of course, argue that socialization is an appeal of any entertainment medium, from discussing favorite books with a friend to attending a movie in a crowd. Games, however, can be (and often are) specifically designed to encourage particular kinds of socialization over others.

Rock Band, for instance, is fun in groups not just because multiple people can play at the same time, but because it actively fosters a sense of cooperation: Players rely on one another and can help each other. If one player does poorly, the song could end for everyone, so other players must be mindful about when to save floundering teammates by triggering “Overdrive” mode.

Many team-based action games also rely on conversation between teammates not just to chat about how your day went (though players use games as a social gathering for just that purpose), but also to share tactical information and plan group actions against opponents.

Less formally explored, however, are more one-way generosity mechanics — helping out players without necessarily receiving a reward for oneself. That may sound like it would be a contradiction in terms: Once you design a system that recognizes one player helping another, doesn’t that necessarily imply a reward for the charitable player, making this more appropriately described as cooperation? I’d argue that this isn’t always the case, but such a system may have yet to be designed in a truly satisfying way.

FarmVille, for instance, does allow for cooperation-free generosity by giving players the option to send one another gifts at no cost. One could ask for reciprocity (and players often do), but some players happily use this feature simply because they enjoy giving gifts to others.

Unfortunately, the system is designed better as a marketing tool than as an appeal because the result is often unwanted Facebook messages notifying players’ friends that they have a “gift” waiting in a game they don’t play. Some MMORPGs also offer formalized “mentor systems” (see Shadow Cities or Final Fantasy XI), suggesting that there is room to actually design for such appeals, though this is more typically arranged by players through less formalized means.

Recreation

Recreation refers to processes of renewal and pastime, which typically means using a game to adjust one’s psychological or psychological state. Related appeals include mood-management (toward relaxation, elation, amusement, or other emotions), distraction (actively avoiding thinking of painful or difficult stimuli), contemplation (pondering thought-provoking issues), and exertion (getting physically energized through play).

The broadest of these appeals is mood-management. I offer this as a single appeal, rather than offering each type of mood-management as its own appeal (relaxation, amusement, excitement, etc.), not only because that list would quickly get unreasonably long, but to make a distinction between appeals as play-behaviors and emotional states as their end result.

That said, it’s worth making note that mood-management encompasses a great many more states than “having fun.” flOw, a slow-moving, soothing game, was specifically designed to show how games might encourage relaxation rather than elation. Shadow of the Colossus and Final Fantasy VII have received praise for sometimes effectively encouraging sadness over happiness. Players choose different games based on context, depending on their company and their preferred mood.

Contemplation is a related appeal, perhaps even part of mood management. Passage, for instance, is a short game with subtle implications rather than an obvious goal for “fun.” It’s a game that is calculated to make you think, rather than to make you enjoy yourself. Distraction is another related appeal, and one that may not sound very worthwhile, given that it can be taken to refer to shutting out other responsibilities that need to be dealt with (as with compulsive gambling, for instance). Even so, distraction is at the heart of why games make such excellent therapeutic tools in hospitals, effectively acting as non-medicating pain-reducers.

One of the main reasons I think it’s important to give recreation its own category is that it includes the main appeals that have skyrocketed many so-called “casual” games to success, from Facebook and mobile “social games” to motion-control games on the Wii and other systems. Regardless of whether critics or designers find their tactics to be nothing more than extortion, the success of skill-free games like FarmVille and Tiny Tower should suggest that these games are giving players something that they want.

Rather than lamenting that players are unfortunate dupes, it’s worth considering that maybe players are getting precisely what they want from these games, at a price players are willing to pay. And while many traditional gamers lament that Wii “shovelware” games do little to scratch the surface of what motion control technologies could do, it has done little to slow sales of the system. Even the least thoughtfully-designed Wii game might offer some opportunity for pleasant physical exertion in the hands of someone eager to cut loose in the living room.

Subversion

Subversion refers to behaviors that run counter to norms and expectations, as defined by society and game logic alike. Related appeals include provocation (actively antagonizing other players through “inappropriate” behavior), disruption (breaking game logic and exploiting glitches), and transgression (“playing evil”, such as killing friendly NPCs).

I group these appeals because each involves breaking some kind of rule. Provocation involves breaking implicitly agreed-upon social norms about how people are expected to act in games and in polite interaction. Disruption involves breaking rules hard-coded into the game — and, if you use those rules to your advantage in a multiplayer game, breaking the aforementioned social contract of “fair” play.

Transgression is generally considered the least offensive of these, as the rules broken are broader cultural norms, and generally permitted by fellow players and game rules. Nevertheless, I group this sort of transgression along with the other subversion appeals because the root of enjoyment behind this activity is, as more than one person said in the course of my research, “being a dick”. The basic appeal of each of these activities revolves around doing something you know you’re not supposed to be doing.

I give these attention as valid appeals, rather than dismissing them as griefing, glitching, and cheating, simply because so many players enjoy doing this sort of thing that it may be helpful to avoid thinking of it as a deviant behavior. (For a comprehensive account, see Mia Consalvo’s book, Cheating.) How can designers account for this appeal?

The most obvious answer, of course, is that actually accounting for subversion neuters it entirely. How can you encourage rule-breaking and also leave the thrill of breaking the rules? That doesn’t necessarily tell the whole story, however. Designing a path for “evil” play is one way to offer a transgression appeal: In Fallout 3, for instance, the player breaks no game-logic rules by sharing a friendly meal with cannibalistic murderers or by selling a small child into slavery, but still gets to enjoy bucking traditional narrative expectations and social norms.

Designers can even formalize provocation in a game where copping an attitude might be an expectation of the community: The aforementioned player-on-player brutality of Gears of War (with the option to punch an opponent’s face for several seconds even after you’ve beaten them) might arguably be called a formalized approach to griefing. These offer ways to break the rules of normal social conduct without breaking the rules of the game.

Admittedly, it’s trickier to suggest ways to encourage players to actually break the game rules without running the risk of actually destroying the game (or at least crashing multiplayer servers). Cheat codes and Easter eggs offer a sort of sanctioned subversion — breaking game rules on a controllable scale.

Could we imagine a game that even more purposely encourages this sort of appeal — say, a Matrix-style science-fiction game where glitching actually makes sense in the context of the game world, and interesting glitches get formalized as part of the game rules? I certainly wouldn’t want to be the one in charge of making sure the game doesn’t fall apart as players scramble to find ways to do just that, but it would be interesting to see some developer try something like it. For now, subversion may represent the most unexplored category of appeals to date.

Complements and Conflicts Between Appeals

Reading over these appeals, you may notice that they aren’t at all mutually exclusive — and, in fact, that’s entirely the point. This allows us to discuss the many ways in which they intersect for good and ill, and how to design games to capitalize on these intersections.

Finding and exploiting a game’s glitches, for instance, offers subversion-related appeals in breaking the rules, but it may also offer accomplishment-related appeals in giving oneself an edge against opponents, or even just in uncovering the secrets of the game system. Playing Dance Dance Revolution offers accomplishment-related appeals in achieving a high score on difficult songs, socialization appeals in dancing alongside other players, and recreation appeals through physical exertion.

Different game appeals sometimes map to different game mechanics, but they don’t have to. A game can offer imagination appeals entirely separately from accomplishment appeals by having narrative cutscenes that feel completely irrelevant to player input, but it could also blend imagination and accomplishment by making dialog interactive, even challenging.

Dialog scenes in Mass Effect 2, for instance, offer an appeal of directorship by allowing the player to choose how to respond, but there’s not much room for a the appeal of perfecting one’s skills; some responses yield objectively better results than others, but the best responses are clearly color-coded, and generally achievable so long as you choose consistently “good-guy” or consistently “bad-guy” responses.

In contrast, dialog scenes in games like L.A. Noire and Deus Ex: Human Revolution add an additional layer of challenge by requiring the player to gauge characters’ facial expressions and body language in choosing the most effective responses.

No less important than blending appeals, of course, is anticipating how different appeals might conflict with one another. This offers designers an opportunity to prioritize features, or offer additional context for features, based on the appeals they most want to encourage. As I described in an article in Eludamos, for instance, “dying” in a game is usually hugely disruptive to storytelling, but it’s typically considered an appropriate way to make players feel they have something at stake in failure.

In other words, it’s a traditionally-accepted concession to accomplishment appeals at the cost of imagination appeals. Some games do, however, anticipate this conflict and attempt to compensate for it, such as by explaining away death through narrative means — reviving as a clone in BioShock, or finding out that the death was a mistake by an unreliable narrator in Prince of Persia: Sands of Time.

A more dramatic approach is to completely exclude certain features to ensure that the appeals you most want to encourage are most salient. Consider, for example, how game designers might deal with the potential conflict between imagination appeals and socialization appeals. A cooperative, multiplayer campaign like in Borderlands or Gears of War offers opportunities for socialization with friends, and may even help make challenges more manageable — but these appeals may come at the cost of imagination if your friends have a tendency to chat over cutscenes.

Demon’s Souls also features cooperative and competitive multiplayer mechanics, but it prioritizes imagination appeals (like being drawn into a tense atmosphere) over socialization appeals (like chatting with friends). You can’t communicate directly with other players through voice chat, but only interact with them as ephemeral ghosts or indirectly, by leaving brief messages written on the ground. By forcibly isolating players in their own dangerous worlds, the result is arguably much more thematically and stylistically consistent than it could have been with a voice chat function.

While it won’t always be obvious which appeals are likely to conflict and why, describing game features according to this approach does at least offer a means to critique what has worked and what hasn’t worked in existing games. And by considering all of these appeals on even standing, it’s my hope that we might see more games that experiment with prioritizing some of the least widely utilized appeals, for the sake of innovation, exploration, and — if I may be permitted to say so — fun.

Conclusion

This theory of game appeals represents an attempt to cover a lot of ground. That said, I see this not as an all-encompassing, universal taxonomy, but as a starting point for a way of thinking about games that sees potential value in a broader range of design approaches.

Moreover, I also see plenty of room for additional appeals, or for taxonomical reshuffling as further research recommends. Do skill-free “social games” have more complex workings than I give them credit for by only describing their appeals in terms of recreation and chance accomplishment? Do motion-controlled games like those on the Wii and the Kinect — or athletic sports, for that matter — deserve an entire category separate from recreation, breaking kinesthetic activity into more varied and nuanced appeals? I would have loved to have investigated such questions myself more fully, but I’m hoping others will suggest how to fill in the gaps.

Beyond being a mere theoretical exercise, however, I also hope that these discussions can lead us to designing an even broader variety of thoughtful and innovative games. When designers and developers define games as obstacle courses whose primary purpose is to elicit “fun,” we miss out on other kinds of engagement and experience. And when we describe players as if they could be so easily fit into a small handful of categories themselves, not only do we forget that we can intrigue and delight one player on multiple levels, but we run the risk of never reaching the players — or creating the genres — that we have yet to discover. (Source: Gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号