解析游戏趣味元素之心流和艺术

作者:Tony Ventrice

(在本系列文章第一部分,Tony Ventrice通过7种游戏趣味元素探讨了游戏化操作的可行性,并通过第二、第三、第四部分论述了成长&情感、选择&竞争、身份&故事元素特点,本文探讨的是心流和艺术元素。)

心流

我曾花大量时间查看几乎每款成功游戏在App Store所收获的用户评论。我发觉出现频率极高的一个词就是“令人上瘾”,这看起来就像是用户给予游戏的最高荣誉。但为什么大家要选择这个字眼?“上瘾”不是一件坏事吗?

而当你开始玩这些游戏时,就会发现这种形容并无不妥。这些“令人上瘾”的游戏几乎像磁铁一样黏住你,它们兼具挑战性和简单性,而且还会让你爱不释手,直到手机电量耗尽为止。

成瘾性正是成功游戏的普遍特征,在游戏产业中这种特性又常被称为“心流”状态。

心流理论

早在电子游戏问世之前,心理学家米哈利.契克森米哈赖(Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi)就已经提出“心流”之说,他对“心流”状态的描述如下:

“完全融入一项活动中,从而达到物我两忘的境界。在此期间你的任何动作、移动和想法都与前者紧密衔接,就像是在演奏爵士乐。你全身心投入其中,并将自己的技能发挥到极致。”

他在著作中指出人们达到心流状态需具备的四个前提:

*内在奖励感

*清晰无障碍的目标

*即时反馈结果

*平衡的技能水平和挑战

这种观点对游戏设计师来说并不陌生。事实上,从开发电子游戏到驯狗等各个领域,我们不难看到许多关于如何创造粘性体验的文本指导教程。

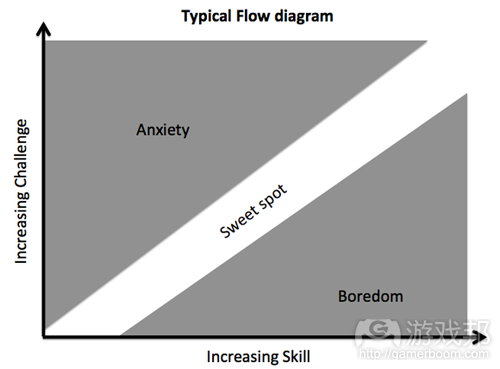

很显然,人们对心流状态的讨论多集中于第4点,即平衡的技能水平和挑战。如下图所示:

有位名为Jenova Chen的学生(游戏邦注:他后来成立了《Journey》开发商Thatgamecompany公司)所写的硕士论文《Flow in games》及其衍生游戏《Flow》获得了大量关注,他的文章探讨了玩家对游戏动态难度调整的问题。

我发现这里有两个问题,将心流定义为难度平衡之下的状态,实际上忽视了没有任何难度曲线的情况;它还使人们讨论的重点引向人们的一般投入性,背离了心流这一词应该探讨的高度投入性问题。

针对玩《模拟人生》和赌场老虎机这种几乎没有任何难度的活动,我们又该如何解释其中的心流状态?所以我认为“难度”只是处理更基本层面因素的一个内容——这是我们多年来所忽略的一个重要细节。

挑战?

将心流描述为一种技能测试时,契克森米哈赖的理论并不完全正确?他早期的测试样本多为一些艺术家,他们能够执行外行人所不擅长的绘画任务。

杰出的音乐元老,心理学家和神经科学家Daniel Levitin在自己的《This is Your Brain on Music》一书中提出了1万个小时理论,声称无论是下棋、足球、绘画、写作还是玩吉他,人们都需要积累1万个小时的实践方有望成为其中的能手。

我们是不是可以假设,契克森米哈赖所观察的艺术家都已经身经百战,能够利用自己积累了无数小时的经验,轻而易举地完成任务?只要经过足够的训练,人们所掌握的技能就会变成一种自动行为,能够不费吹灰之力地准确完成任务。那么资深钢琴家按错键,职业足球运动员运错球,专业画家调错颜色的机率有多大?

我认为,对大师级人物来说,这些细节问题并非挑战,它们是一种“自发”完成的行为,大脑此时已经从技术性挑战转向一个亚问题。对艺术家来说,亚问题就是创造自我表现的能力;对运动员来说,亚问题就是打败竞争对手。总之大脑会自动参与这两个不同层面的持续活动。

*有一半大脑负责处理人们已掌握的一连串自动学习选择。

*另一半大脑则关注一连串主观性、创造性选择。

对游戏、艺术、体育到写作等各个领域的心流状态来说,这两者都是不可或缺的因素。创造性选择可以让人们获得愉悦而新鲜的体验,而潜意识中的自动性选择则可让人保持高度集中,以免大脑陷入漫无目的的状态。

有调查研究人员证实,如果一位行家犯下惊人的错误,这多半与其亚目标和自动性选择的切换有关,这不但可表明人们确实存在这两种层次的思维,而且还能证明成功者一般都会在亚目标的表现上拥有过人之处。

在心流状态研究群体中,也有一些人质疑契克森米哈赖所提出的挑战–技能平衡这个条件。有研究人员认为人们对挑战和技能的概念看法并不统一。

执行自动学习选择

游戏的自动学习选择模式主要建立于两种基础之上:

*原先玩过的游戏

*人类固有的技能

原先的游戏:在这种情况下,人们需要掌握在之前所玩游戏中所学到的复杂技能,例如玩新款第一人称射击游戏(FPS),就需要以上千个小时的射击游戏经验作铺垫。

若要向从未玩过3D游戏的人展示一款现代FPS的技能设置,只要以《现代战争》进行示意就行了。看到新手在这种游戏中频频碰壁,甚至无法以直线行进和绕过障碍的情况,就足以说明人们精通其中技能到底需要积累多少经验了。

固有的技能:在此情况下,人们不需要费太多功夫,潜意识下就知道要怎么玩游戏。

玩过《模拟人生》的人可能早就知道怎么拖放鼠标,他们本能地知道要为睡觉或饥饿的虚拟形象做些什么。而参与Yahoo! Answers这种问答网站的活动,也基本上不需要经过什么训练。

执行主观创造性选择

在讨论创造性选择之前,我想先以一些经典游戏为例进行剖析。

《宝石迷阵》

我记得自己首次在大学室友的电脑上接触这款游戏时,第一个念头就是“这游戏真傻”,第二个想法就是“我刚才的2个小时都做了些什么?”,第三个想法又变成了“这游戏真傻”。

这第三个想法迫使我结束浑浑噩噩的状态,认真思考游戏过程中发生的情况。

很显然,《宝石迷阵》的“首要目标”就是永远不让你从游戏中分心。该游戏采用了一个持续,无尽重复的简单选择决策循环。

另一点就是,《宝石迷阵》真是“无休无止”。最初游戏中有一个避开失败状态并优化分值的创造性挑战,但最后你完全掌握了避免失败的要领时,游戏就真的变得永无止尽了。

但我并不是说原版《宝石迷阵》存在瑕疵——-就算市场上并没有出现这款游戏的续作或克隆版本,它也仍是史上最成功的休闲游戏之一。但《宝石迷阵》并没有停滞不前,其进化过程就很能说明创造性选择和心流状态潜在的额外条件之间的联系。

创造性的机会

将我在2001年玩过的《宝石迷阵》与其仿制品及衍生产品(游戏邦注:例如《Jewel Quest》、《宝石迷阵闪电战》等)相比较,就不难发现后来者添加了许多新内容。例如炸弹、星星石、超立方体、任务模式、不规则桌面以及逐渐增长的宝石颜色等。这些游戏最初玩法与原版《宝石迷阵》无异,但添加了许多使游戏更有趣味的亚目标。

我认为,《宝石迷阵》的基本玩法已经随时间发展而为核心玩家群体所掌握,原先的创新内容也已被玩家吃透,所以它需要新的创造性内容(即能够最大化分值和响应障碍物的内容)满足玩家需求。可以说,玩家的需求就是游戏的成长空间。

成长

我在之前的文章曾提到,人们至少有4种实现个人成长的途径(即学习、顺序、克服挑战和建立关系)。在《宝石迷阵》的案例中,玩家的高级成长目标就是“克服挑战”。如果从心流状态=难度平衡的角度来看,人们在多数游戏中进入心流状态一般是因为他们将克服挑战视为首要的成长形式。

但进入心流状态未必需要不断增加挑战。使用Facebook也是一种容易进入心流的活动,但Facebook活动并没有什么难度。“建立联系”和“学习”才是Facebook平台上的成长形式——它让人们建立联系,并从他人的分享中学到新知识。

《愤怒的小鸟》

《愤怒的小鸟》中的心流发展方式与《宝石迷阵》有所不同,后者是通过不断添加挑战来满足玩家追求的新鲜感,而《愤怒的小鸟》却是通过添加新内容来解决这个问题。

该游戏总会定期推出新关卡,新敌人和新鸟类,这些新内容呈现了三种成长形态:学习(这取决于新机制在玩家已知系统中的简单程度),克服挑战(解决空间谜题)和顺序(玩家需打通所有的新关卡才能进入下一关)。

与《宝石迷阵》似乎“一成不变”的谜题不同,《愤怒的小鸟》会推出制作精良且需在列表中挨个打通的新关卡。即使某个关卡与前者极为相似,玩家也还是难以抑制打通列表中所有关卡的欲望。

《FarmVille》

《FarmVille》表明游戏也可以让更广泛的群体进入心流状态(而不只是局限于之前提到的艺术家或专业人士),它与其他多种游戏的区别在于,其心流来源有所不同。

该游戏的心流状态几乎完全取决于“顺序”这种成长形式——例如清理田地、搜集物品、赢取新装饰物品的顺序。

老虎机

老虎机是心流状态的一个普遍例子,并且可能是最难以定义心流概念的测试工具。

老虎机的确能够让玩家沉迷于大量按钮、旋转画面、闪光灯和嘈杂噪音中不能自拔,但它的主观决策条件及成长机会又是什么呢?

如果我们站在一名老虎机常客的角度上看问题,可能就会发现我们做决定时要先有一个直觉。首先让我快速解释一下何为决策。

简单地说,决策就是:

出现一个命题,接着进行预测,最后就是做出决定。

举例来说:

决策1:你午餐想吃什么?

要回答这个问题,你的大脑首先就会创建一个选择列表:街旁的墨西哥餐厅、隔壁的三明治,拐弯处的新加坡餐厅等。然后大脑就会开始预测你在每个地方获得的享受。这时候可能也会考虑到荷包里的钱、时间成本、就餐环境等其他问题。最后,你的大脑就会择其最优者而行之,并做出最后决定。

决策2:要不要在这个老虎机中丢25美分碰碰运气,还是直接走开?

此时你的大脑就会根据之前的投币历史,评估这次的成功机率。也会考虑你目前的资金状况,你“需要”赢钱的强烈程度,你“最近一次”得手的时间,你是否“值得”付出等等。考虑到这一系列问题后,大脑就会据此做出判断。

也许有人会说人们对老虎机的命题和预测毫无理性,但我认为理性并非人们做出决定或进入心流状态的必要条件。

我们很难定义针对老虎机的“成长”模式。可能它根本不存在什么成长模式——人们只在乎赢钱的机率,或者说老虎机至少包含一些“顺序”形态,即人们只要加以观察就能掌握的随机性系统的运行原理。

我之所以要在本文再次提到“成长”元素,原因在于:成长是心流的必要条件,而心流却并非成长的必要条件。没有成长,心流的主观性选择终将丧失趣味性,而没有心流,游戏仍有可能吸引用户(只是不会像心流那样具有强迫性)。

心流的三个层面

*一连串已掌握的自动性选择

*一连串的主观性、创造性选择

*成长来源

心流的运用

了解上述三个层面,我们应该就会明白并非任何体验都可以因心流而被“游戏化”。事实上,这里的必要条件存在局限性,尤其是那两串无止尽的交互过程。多数想要添加游戏机制的活动都不具有游戏的交互性。似乎只有Facebook和YouTube等一些网站具备心流特点。这些网站究竟有何不同?

消费内容

Facebook和YouTube是互联网上的两大内容网站。它们通过消费内容而实现心流状态。在这些网站中,点击和查看就属于自动性选择,而决定是否要“赞”一下当前内容,做出快速反应后又决定下一步要看什么东西则属于主观性选择。

这些网站因拥有海量且无尽的连续查看/回复循环而满足了心流的基本条件。它们不断提供新内容,让用户通过“学习”和建立“联系”而获得成长。从这些网站中我们不难发现,若要维持一定的内容数量,网站就必须要有用户创造内容。其他拥有心流特点的网站还包括 Yahoo! Answers、Quora,以及Digg、Fark和Reddit等评论/社交书签网站。

创造内容

心流的另一个来源就是创造内容本身的过程。但创造内容也面临与创造艺术或音乐一样的“专家”门槛——多数情况下,并非所有人都能够创造内容。假如用户面较为狭窄和限制性,这就不算是一个问题。例如维基百科就可以在一个小社区中保持心流状态。

对于更广泛的大众群体来说,Facebook才是一个创造内容像消费内容一样简单的典型网站。Yelp这种评价网站的创造流障碍也比较小,除非用户吃遍了它所提供的所有餐馆。

若说游戏真存在什么“魔力”,我想那就是心流。虽然心流并非游戏独有的特点,但游戏确实可为大众带来心流体验。《吉他英雄》可能就是一个绝佳例证。多数人也许永远都不会深入学习一种乐器,并达到个人创造性表达的境界。

《吉他英雄》从音乐流中获取灵感,删减了人们进入这种状态所需投入的上万小时的时间成本,让玩家随意拣起一把塑料吉他就能够直接进入这个神奇的心流境界。这和玩真正的乐器所进入的心流并不相同,甚至也并不相近,但对一些没有真正接触乐器的人来说,这却是一种非凡的体验。

艺术的趣味

关于艺术的问题

看画像的乐趣在哪?听音乐的乐趣又是什么?

我认为在本系列文章所讨论过的内容中,艺术无疑是最为神圣的话题。艺术通常被视为一种“个人”体验。它会与灵魂对话,与我们内心深处的自我及身份相通。

若要解释艺术的趣味何在,我只能先说说自己对艺术的定义及其意义的看法。

我认为艺术是以下几个层面的趣味性合体:

*感觉

*顺序

*智力激发

*身份

感觉描述的是人们看到、听到、觉得、闻到和尝到的情况。我曾在之前的文章中将感觉纳入趣味列表。它虽然是一种有效的趣味元素,但我并不认为它适用于游戏化项目。创造愉人的感觉体验之人并不一定是游戏设计师,但必须是艺术家。

顺序是成长的一个层面。我认为它与艺术的关联在于,艺术拥有风格。并非人人都会欣赏或到注意到艺术风格,但对一些人来说,鉴别和分析艺术风格正是检验/比较新实体与一系列隐性规则相异之处的实践过程。看到一致的风格可以令人产生和谐之感。

人们对新风格(或原有风格的进化)的认知也将催生一种新顺序——新的隐性规则。

智力激发描述的是下意识地解释艺术内涵的行为。并非所有艺术均是如此,但有些艺术确有其显性含义。探索和讨论这种含义既是一种发现顺序(通过他人的艺术性表达以强化验证个人想法),又是一种挑战行为(通过解释线索或追随一系列推理而找到艺术内涵)——这两者均属于成长的重要层面。

身份会根据个人和集体体验来定义艺术。对个人来说,你的艺术喜好可定义你的身份,它可以说明你所重视的感觉和情感,甚至是你的顺序感和修养。对集体来说,以同种方式“打动”你和他人的共同艺术体验,能够加强大家的社交联系,并确认你的感官喜好、顺序感和修养。

总结

这是我对于游戏趣味性组成要素这个话题的最后一篇文章,我并不认为所有游戏都要囊括本系列提到的一切趣味元素,只希望本系列文章能够启发各位设计出更有趣味性的内容。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Gamification Dynamics: Flow and Art

by Tony Ventrice [Design]

[In the final installment of his series on Gamification Dynamics, Badgeville's Tony Ventrice puts the concept of flow under the microscope, sharing new research that provides a new window into the popular concept -- as well as examining what aspects of art appreciation translate well to games. The full series includes the original framing article as well as three prior examinations of dynamics: part 1, part 2, and part 3.]

Flow

When I was working on iPhone games, I spent a good deal of my time reading user reviews of virtually every successful game to grace the App Store. One thing stood out time and time again, and that was the word “addictive.” It seemed to be the highest compliment imaginable. Granted, the audience wasn’t the most erudite, but why this word? Isn’t addiction a bad thing?

Once you played these games, the language started to make more sense. These “addictive” games had a way of completely absorbing your attention, they were both challenging and simple and had a way of preventing you from setting them down until your battery died.

What the customers were calling addiction is a common phenomenon in successful games and tends to go by the name of “flow” in the industry.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

The term “flow” can be attributed to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a researcher who built a career on the topic before video games had even been invented. In an interview, Csikszentmihalyi described flow as:

Being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost.

In his writings Csikszentmihalyi typically mentions the following prerequisites to flow:

•Intrinsically rewarding

•Clear unobstructed goals

•Immediate feedback

•Balance between ability level and challenge

To a game designer, these should not be surprising. In fact, these are pretty much textbook instructions to building any type of engagement, from a video game to teaching tricks to a dog.

They’re so obvious, in fact, that most discussions of flow tend to focus on only the fourth point: Balance between ability level and challenge.

If you’ve ever seen flow diagramed, it probably looked like this:

A student named Jenova Chen — who later went on to found Journey developer Thatgamecompany — attracted a good deal of attention with his master’s thesis, Flow in games, and an accompanying game, appropriately named Flow. Chen’s focus was on dynamic difficulty adjustment, exploring the concept of player-controlled adjustment of game difficulty.

The two problems I have with defining flow as something that happens when difficulty is balanced is that it ignores flow that occurs in situations that have no difficulty curve, and it draws the conversation into the realm of general engagement, away from the hyper-engagement that the term flow was meant to discuss.

How does one explain the flow-inducing success of activities such as The Sims or Vegas slot machines — activities that have no difficulty at all? The realization should be that “difficulty” is only one way to approach a more fundamental factor — an important detail that may years of assumption may be causing us to overlook.

Challenge?

What if Csikszentmihalyi wasn’t completely correct when he described flow as being a test of skill? His early subjects were artists performing tasks that would certainly seem difficult to an observer with no advanced talent in the field of painting.

Daniel Levitin, an accomplished music industry veteran, psychologist and neuroscientist, proposes in his book, This is Your Brain on Music, that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to master anything, be it chess, basketball, painting, writing or playing the guitar. This is a commonly-cited fact popularized by Malcom Gladwell in his book Outliers.

Is it unreasonable to suppose that the experienced artists Csikszentmihalyi was observing had already been through countless hours of practice and that they did not consider their craft to be difficult at all? After enough practice, mastered actions are so automatic and effortless as to be nearly infallible. How likely is an experienced pianist to hit the wrong key, a professional basketball player to mis-dribble, or a professional painter to fail to anticipate how two colors will blend?

I would propose that, for masters (and even experienced aspirants on their way). the little details are not challenging, they’re automatic; the brain has moved beyond technical challenge and onto a meta-problem. In the case of artists, the meta-problem is creating self-expression; in the case of athletes, the meta-problem is outplaying the competition. The brain is simultaneously engaged in two levels of constant activity.

•One part of the brain is managing a stream of learned automatic choices.

•Another part of the brain is focused on a stream of subjective, creative choices.

In any example of flow from games to art, to athletics, to writing, both aspects appear to be essential: the creative choices keep the experience pleasurable and fresh, while the undercurrent of automatic choices compels absolute focus and prevents the brain from wandering.

Corroboration for this model comes in the form of research into “choking” under pressure. Researchers have proven that the spectacular failure that occurs when an expert does fail can be traced to a change in focus from meta-objective to the automatic, implying that not only do these two levels of thought exist but that successful experts expend all of their conscious effort focused on the former.

Within the flow-research community there also appears to be some doubt with Csikszentmihalyi’s balanced challenge-skill requirement. Researchers recognize that there might be attentional ambiguity when addressing the concepts of challenge and skill.

Implementing Automatic Learned Choices

There are two ways a game can expect to achieve a foundation of automatic learned choices:

•Build on the backs of previous games

•Build on innate human skills

Previous games. In this case, the game implicitly requires a sophisticated set of skills learned from past games, such as a new FPS that assumes hundreds of hours spent playing previous shooters.

All you need to do to demonstrate the expected skillset of a modern FPS is hand Modern Warfare to someone who’s never played a game in the 3D era. The significant amount of investment should become clear as the new player struggles to even move in straight line and navigate obstacles.

Innate human skills. In this case, the game relies on skills most humans have acquired unknowingly through thousands of hours of simply being alive. Anyone who’s played Where’s Waldo was probably, even at a young age, immediately engrossed in spotting that little striped hat and jacket like a pro.

Anyone who’s played The Sims probably already had drag and drop mastered, and intuitively knew what to do with a sleepy or hungry Sim. The same lack of training applies with activities like the face-comparing website Hot or Not or answering questions on Yahoo! Answers.

Implementing Subjective Creative Choices

To discuss creative choices, I’d like to start by dissecting the evolution of a flow-inducing classic.

Bejeweled

I can remember my introduction to Bejeweled on my roommate’s computer in college. My first thought was: This is stupid. My second thought was: What just happened to the last two hours? My third thought was: This is stupid.

That third thought broke me out of my trance and forced me to face what had just happened.

One thing that seemed obvious was Bejeweled’s primary objective is to never let you have a thought that isn’t dedicated to the game. The game employs a constant, endlessly repeatable decision loop of simple choices.

The other thing was Bejeweled is terribly redundant. At first, there is a creative challenge to optimize your score without letting the blocks reach a failure state, but eventually you realize how to avoid failure entirely and the game literally does become endless.

This is not to say that the original Bejeweled was flawed — even if there were no sequels and clones (and yes, Bejeweled is itself a clone), Bejeweled would still rank as one of the most successful casual games of all time. But Bejeweled did evolve, and that evolution is telling of both the nature of creative choices and a potential additional requirement of flow.

Opportunities for Creativity

If you compare that early form of Bejeweled I played back in 2001 with its imitators and progeny (Jewel Quest, Bejeweled Blitz, etc), you’ll find a number of new additions. You’ll see things like bombs, star gems, hypercubes, quest modes, irregular boards, gradually increasing numbers of gem colors, etc. The games typically start out just as simple as the original, but the new mechanics increase the meta-objectives until the game becomes interesting again.

I suspect that what happened is, over time, the basic play of Bejeweled became automatic to the game’s core audience. What was once creative became learned and a new layer of creativity was needed — a new layer of maximizing scores and responding to hazards. Effectively, what was needed was room for growth.

Growth

If you’ll remember, there are at least four ways people can measure personal growth (learning, order, challenges overcome, and connections). In the case of Bejeweled, the higher growth objective is challenges overcome. The reason for the assumption that flow = balanced difficulty in games comes from the fact that, in most games, flow has traditionally been obtained with challenges overcome as the primary form of growth.

But flow doesn’t have to rely on increasing challenges. Facebook is an activity conducive to flow, but Facebook supports no sense of difficulty. Instead, Facebook contains growth in the form of connections and learning — reinforcing bonds between people and learning from the shared discoveries of others.

Angry Birds

Angry Birds takes a different approach to growth in flow. While Bejeweled addresses the need for novelty by increasing challenge through a system of growing complexity, Angry Birds addresses the issue with new content.

Periodically, new levels with new enemies and new birds are released. New content utilizes three growth forms: learning (how simple new mechanics function within the known system), overcoming challenges (solving spatial puzzles), and order (all those new levels need to be completed).

Unlike Bejeweled, which “feels” like the same puzzle over and over again, Angry Birds comes in discreet levels that need to be completed and checked off from the levels list. Even as one level becomes increasingly similar to the last, there is still a compulsive desire to finish the list.

FarmVille

FarmVille demonstrated games can cause flow in a wider demographic of people than was previously believed possible. The difference between FarmVille and many other games is, unsurprisingly, the source of its flow.

FarmVille’s flow relies almost entirely on the sense of growth as order — the order of cleaning, collecting, completing sets, and earning new decorations.

Slot Machines

Slot Machines are a common example of flow and present perhaps the toughest test for any definition of flow.

Sure, slot machines can keep the user occupied with an inundation of buttons, spinning pictures, flashing lights and loud noises, but what about the requirements of subjective decisions and growth opportunity?

To address these I’m going to propose that, if we were to step into the mind of a habitual slot machine player, we would discover there is a perception that decisions are being made. If you’re willing to follow me for a moment, I think it’s necessary to quickly address what a decision is.

At its simplest level, a decision is:

A problem statement, followed by a prediction, and, finally, a determination.

Let’s take a few examples:

Decision 1: What would you like for lunch?

To answer this, the first thing your brain does is create a list of possible options: the Mexican place down the street, the sandwich place next door, the Singaporean place around the corner. Then your brain predicts your expected pleasure at each establishment. Perhaps it also predicts the impact on your wallet, time spent, ambiance and any other possible concerns. Finally, your brain arrives at a choice — a determination of predicted optimal experience.

Decision 2: Put a quarter in this slot machine, or walk away?

Your brain evaluates the history of previous pulls, predicts the likelihood of success on the next pull. Also considered are your current funds, how bad you “need” to win, how “close” you got last time, and how “deserving” you are. All considerations taken, the brain makes a determination of the likelihood of winning and bets accordingly (bet 1, bet 5, 12-ways to play, etc.).

You might point out that the slot machine problem statement and predictions are irrational, but I’d suggest that rationality is not a prerequisite to decision-making or flow.

The growth of a slot machine is a little more nebulous to define. It may be that there is no sense of growth — that the potential for financial gain is enough — or it may be that slot machines contain at least some perversion of order, the implication that behind all the apparent randomness a system exists that only needs to be observed to be learned.

Growth Redundancy?

If you’re like me, it might bother you that growth is a topic here, considering it was already covered previously in its own section. The reason for re-addressing growth is this: growth is a requirement for flow, but flow is not a requirement for growth. Without growth, the subjective choices of flow will eventually cease to be interesting. Without flow, a game can still engage a user (although perhaps not as compulsorily).

Three Aspects of Flow

•a stream of learned automatic choices

•a stream of subjective, creative choices

•a source of growth

Applying Flow

Looking at the three aspects above, it should be clear that not any experience can be “gamified” to include flow. In fact, the requirements are rather limiting, particularly the two endless streams of interaction. Most activities seeking game mechanics are not as interactive as games. A few websites that seem to have flow include Facebook and YouTube. What makes these sites special?

Content Consumption

Facebook and YouTube are two of the biggest content sites on the internet. They achieve flow through binge content consumption. On these sites the stream of automatic choices are clicking and viewing. The stream of subjective choices are deciding whether to like the current content, possibly typing out a knee-jerk reaction, and then deciding what to view next.

With limitless content and endless loops of rapid-succession view/respond transactions, these sites fulfill the basic requirements of flow. A constant novelty of content offers an opportunity for growth in the form of learning and possibly connections. A possible implication to be taken from these sites seems to be that, to maintain a necessary level of content volume, user-generated content is almost essential. Other sites that have flow include Q&A sites like Yahoo! Answers and Quora, and commenting/social bookmarking sites like Digg, Fark, and Reddit.

Content Creation

Another possible source of flow is in the act of creating the content itself. Yet content creation possibly faces the same “expert” limitation as creating art or music — in most cases not everyone is qualified to create content. If the audience is narrow and qualified, this is not an issue. Wikipedia has managed to maintain flow within a small community (although apparently it runs the risk of being bogged down by process).

For the more general population, Facebook is an example of a site where creating content is almost as easy as consuming it. A review site like Yelp also has little obstruction to obtaining content-creation flow, at least until a user runs out of restaurants she’s eaten at.

Concluding Flow

If anything can explain the “magic” of games, I’d say it’s flow. While flow is not unique to games, games bring flow to the masses. Perhaps Guitar Hero illustrates this better than anything. Most people, for better or worse, will never learn to play a musical instrument well enough to reach the meta-level of creative expression.

Guitar Hero took the aspiration of musical flow and cut out the thousands of hours needed to reach it. A player can pick up the plastic guitar and be transported directly into a wonderful world of flow. It’s not the same flow, not even close, but to someone who hasn’t tasted the real thing, slipping into a trance, doubling down on star power and setting a high score while the music harmoniously blares is pretty sweet.

The Fun of Art

The Question of Art

In the comments of previous entries in this series, the question of art came up. What makes looking at paintings fun? What makes listening to music fun?

More than anything I’ve discussed so far, I feel this is the most sacrosanct. Art is commonly considered a “personal” experience. Art says something to the soul, speaks to our deepest sense of self and identity and is generally regarded as safe from conclusive analysis.

In explaining how art is fun, I can only go off of my own interpretation of what art is and what it means.

I believe art is a combination of the following aspects of fun:

•Sensation

•Order

•Intellectual Stimulation

•Identity

Sensation describes the way things look, sound, feel, smell and taste. As you remember, sensation was an aspect of fun I discounted in the process of making my list. While it is certainly valid, it is not an aspect I found practical to gamification. You don’t need a game designer to make a pleasing sensory experience — you need an artist (not to say they couldn’t be the same person).

Order was an aspect of growth. I believe it relates to art in the sense that art can have style. Not everyone appreciates or even notices it, but for those that do, identifying and analyzing style is an exercise of testing/comparing new instances against an implicit set of rules. A sense of harmony can come from witnessing a consistent demonstration of style.

The recognition of a new style (or the evolution of an existing style) involves building a new order — a new model of implicit rules.

Intellectual Stimulation describes the act of consciously deciphering meaning from art. While not all art has explicit meaning, some does. The exploration and debate of this meaning is both an exercise in finding order (validating personal opinions reinforced by the artistic expression of others) and something of a challenge (figuring out what the art means through deciphering clues or following a line of reasoning) — both identified as aspects of growth.

Identity defines art in terms of individual and collective experiences. As an individual, artistic preferences identify who you are; they speak to what sensations and emotions you value, and even your sense of order or intellectualism. As part of a group, a shared artistic experience that “moves” you and others in a similar manner can strengthen social connections and validate your sensational preferences, measures of order and/or intellectualism.

Series Conclusion

This marks the last installment in my investigation into the aspects of what makes games fun. The objective was not to demand all games contain all possible aspects of fun, only to inform the discussion and make the pursuit of distilling and designing fun more productive. I hope you’ve found this journey as thought-provoking as I have.

If you would like to catch up with the previous installments of these series, you can find them linked below:

•Gamification: Framing the Discussion

•Gamification Dynamics: Growth and Emotion

•Gamification Dynamics: Choice and Competition

•Gamification Dynamics: Identity and Story(source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号