分析游戏概念定义及包含的各类交互机制

作者:Keith Burgun

最初的《俄罗斯方块》提供的是更为随机的方块形状;也就是当你在游戏时,你并不能确定下一个竖直形方块何时才会出现。如此使得玩家只能面对较为模糊的选择。

而最新的“7袋”方块系统(即将7个方块装进一个带子里,每一次只能放出一个,如此便确保你至少能够在14个方块轮回中获得一个竖直形方块)设有“控制箱子”,通常在5次或6次循环后便会出现“下一个”箱子;以此来看现代《俄罗斯方块》很大程度上体现的是一种执行性。也许你喜欢现在的《俄罗斯方块》,认为这种改变是正面的;这也没错,但是不管怎样,现在的游戏的确丢失了一些之前游戏所拥有的优秀元素。

游戏概念

我认为游戏属于具体的内容。

我的意思是,只存在一种特殊的概念可以被我们称之为“游戏”,而这种概念又不同于我们用于数字游戏世界中的泛泛术语。电子游戏玩家将任何有关数字谜题、交互式小说、模拟器,甚至是数字制作工具内容都称为“游戏”(或“电子游戏”)。

其实从本质上来说,任何有关数字、交互或者用于娱乐消遣的内容都可称之为游戏。而字典上的定义更泛,它将游戏称作一种“娱乐或消遣方式。”如果照这么说,看电视也是“游戏”了?如果吃一罐豆子能让你感到开心,这也算是一种“游戏”?

但是关键就在于,的确存在一种特别的事物,它既不是玩具,也不是谜题或者其它任何我所提到的事物。这是一种从过去到现在一直存在的事物,直至今天还繁荣发展着。除了“游戏”,我们想不出其它能够更好描述它的术语,所以我将在本篇文章中贯穿这一单词。并且因为会涉及到“所有数字交互娱乐”,所以我也将使用“电子游戏”这一术语。

我将游戏定义为“一种规则系统,代理们在此做出一些模糊的决策并相互竞争着。”我们需要注意的是,“代理”不一定都是人类,有时候其中一方指代的是系统(就像在单人玩家游戏中)。而“模糊决策”尤为重要,我将在此详细分析这一游戏中最重要的元素。

这是一种指示性理论(从一种完全不同的角度去看待游戏),而不是描述现有的一些事物。换句话说,电子游戏(我更想采用手机游戏术语中的“应用”)的谜题也具有游戏元素,游戏也具有模拟元素。我想说的是,因为“游戏”这一术语的模糊性及其本质属性,我们有时候也会遗忘(非故意的)这种有意义却模糊的决策,特别是在面对单人玩家数字游戏时。

什么促使决策富有意义?

肯定有些人已经忘记了如何做出一些有趣且困难的决策,并且是我们难以收回的决策。

游戏中总是存在各种特殊的决策,这些决策具有以下特性:它们是有趣的、困难的,并且答案总是模糊不清的。除此之外,这种决策还必须是“有意义的”。

我所说的有意义并不是指个人意义,如“他们让你反思你与父亲之间的关系”(尽管有时候也会体现出这点)。这里的“有意义”是指你的决策在游戏系统中必须是有含义且有影响力的;它们会引起一些新的挑战,更重要的是它们将影响游戏的最终结果。

也许有人会说,所有的电子游戏,包括谜题、模拟器或玩具也包含某种形式的“决策”。这也没错,但是这些内容推动玩家做出决策的方式却完全不同于游戏。就像你在解决谜题时所做出的决策只有正确和错误之分,你在面对模拟器所做出的决策也没有明确的上下环境,所以很难有意义。

互动系统的等级

正如我所说的,如果从一个广泛的层面来看,各种不同类型的媒体也能够被称为“电子游戏”,但是我们也清楚,如果离开数字领域,游戏便是一种特殊内容。就像Toys R Us(游戏邦注:一家知名的玩具公司)的员工很清楚如何区分谜题和桌面游戏,因为它们彼此具有属于自己的不同特性。

我创造了一个图表以描绘“游戏”不同类型交互系统之间的关系:

这一图像呈现出了交互系统的各个等级。

模拟器(如《Flight Simulator》、《模拟城市》和《Dwarf Fortress》)——模拟器是一种互动系统,主要目标是模拟其它内容。

模拟器与游戏的一个有趣不同点是,我们没有理由抱怨模拟器缺少乐趣。因为模拟器的内在要求并没有乐趣这一点,它们更关注于模拟其它内容。

如此,你可以通过模拟《Dwarf Fortress》中有趣的内容或者模拟植物种植而创造出一款模拟游戏。但是应该注意的是,即使是《Dwarf Fortress》,也不一定存在一些特别有趣的内容值得你去效仿。

我想起自己曾经玩过的一款游戏,游戏中我的堡垒从未受到任何侵袭,并且我会长达好几个小时没有任何事做。这算游戏吗?我真的非常失望。但是后来考虑到这是一款模拟游戏,我也就释怀了。

更确切地说,模拟器与游戏的真正不同在于,模拟器不是一种竞赛类型,而游戏则是。当然了,你也可以创造一款“竞赛类模拟游戏”,但是不管怎么说,竞争都不是模拟的内在属性。

竞赛(如举重比赛,《吉他英雄》,《西蒙》)——所有的游戏都属于竞赛,但并非所有的竞赛都属于游戏。因为竞赛虽然具有竞争性,但是它对有意义的决策却没有特定要求。通常来说这只是一种单纯的测量能力,就像一个简单的问题“你能够举起多少重量”,或者在《吉他英雄》或《西蒙》中,“你能否快速记住这些顺序?”也许在某些情况下看来,竞赛与游戏之间的区别有些模糊,但是我们中的大多数人应该都能直接区分出这两者的不同。

但是《吉他英雄》却是个例外,我想很多人肯定会因为它是一种竞赛而非游戏感到惊讶吧。首先我们需要明确,说任何内容“不是游戏”并不是一种价值判断,尽管有时候我们也会做出错误的判断。我个人认为《吉他英雄》更倾向于竞赛而非游戏是因为它所体现出来的是纯粹的能力测量,并且我在玩《吉他英雄》时也很少能够做出有意义的决策。

谜题(如《传送门》的一个关卡、七巧板和一道数学难题)——谜题也是一种“问题”,并且谜题总是拥有一个正确的答案,也就是“解决方法”。

有些游戏也能够进行破解(游戏邦注:即“完全信息”游戏,如象棋,玩家知晓游戏状态的所有信息),但是如果玩家知道如何解决一款游戏,游戏也就失去了乐趣(就像除了儿童玩家,大多数人都能够轻松解开一字棋游戏,因此这并不适合成年玩家)。而谜题则是本身就具有自己的解决方法。

那么谜题是否包含“决策元素”?我想应该是没有的,至少没有像游戏那样的决策。谜题不是游戏,因为尽管有些谜题允许玩家作决策,但是这些决策却与最终结果没有关系。关于谜题最重要的一点是玩家是否能够做出正确的决策。

如果一道数学题是问“4+6=?”你回答“10”的话,你就算解决了这个谜题。不管你在回答这一谜题的过程中做了什么,都不会改变这个答案。也就是尽管你能够在寻找答案的过程中做决策,但这些决策不会对谜题造成任何影响。而在游戏中,玩家所做出的决策将影响着游戏状态的改变及游戏结果。所以在游戏中,玩家的决策非常重要,这是在谜题中体现不出来的,因此我才会将游戏与谜题区分开来。

决策的敌人

我发现了三种将会影响我们游戏中有意义的决策的主要问题,即角色升级,保存游戏以及基于故事情节的结构。如果游戏采纳了我所提到的游戏力量,便会自然地避开这三个问题。

角色升级。理想的情况是,随着游戏的发展,游戏难度也将随之提高。然而我们所面临的情况是,随着游戏的发展,我的游戏角色的能量也将随着提高。

而设计师为了配合角色能量的发展也进一步加深之后游戏的难度,但是却因此导致玩家瞬间无所适从,这也是为何我们在电子游戏中总是难以做到平衡游戏的一大原因。

本质上来看,你正尝试着去撞击一个移动目标。假设玩家的游戏技能将越来越厉害,那么游戏角色也会变得越来越强大,但是这两种情况的出现却是无规律的,从而导致游戏后面阶段难度系数的不平衡。

任何玩过《最终幻想》并坚持到最后的玩家都会支持我的这一看法(我记得在《最终幻想VII》中,我的Cloud可以轻易击败最后的boss)。我想这些游戏的设计师应该知道这些问题的存在,并且他们可能是故意表现出这种“简单性”吧。

当然了,如果你的游戏过分简单,你的决策也将不再有意义了(就像在我的角色Sephiroth所面临的战斗中,我的决策便失去了意义,因为根据该角色的属性我能够预见其结果)。

保存游戏。我想说速存功能(或类似的功能)应该算是电子游戏中“最强大的武器”吧。因为这一功能很明显,所以我想简要说明:基本上来看,玩家在游戏中的任务就是尽最大努力获得成功,或尝试做出最合理的移动。游戏允许玩家在任何时候都能够保存游戏并再次加载游戏;所以当玩家面临一个复杂的决策时,他们便会选择保存游戏,再做出决策。多荒谬啊!再次加载游戏并选择第二扇门!这样谁都能精通游戏吧!

保存游戏所存在的问题便在于它将阻碍我们做出有意义且能够影响游戏的决策。如果玩家能够在做出错误选择后重新加载游戏,那么他之后所做出的选择也就不能够再影响游戏结果了。如果玩家能够在面临每个挑战前保存游戏,那么他们所面对的竞赛也不能够称之为竞赛了。最后,这也算是一种可预见的结果,即不管如何,最终玩家都能够获得胜利。

当然了也有些持有反论点的人会说道:“如果你不想在陷入困境时重新加载游戏,那你就不要这么做啊!”如此我便不得不创造一个额外规则,即“仅对部分人适用的规则”,面向那些使用保存游戏功能的玩家。但是也有一些游戏将这一机制完全融入游戏玩法中。

基于故事情节的结构。以前的电子游戏从未出现过基于“成就”的游戏理念;反倒是更多地体现出“竞赛”元素。而如今,几乎所有游戏都拥有一个漫长的竞赛过程,并以分数累积为结束点。这种基于成就的游戏心态大大违背了我们所说的“有意义的决策”。

首先,大多数基于故事情节的游戏都很长。尽管从历史上来看,大多数游戏的游戏时间都在10分钟至几个小时之内,但是现代游戏却认为不耗上20几个小时或者更长时间难以表达出“成就”。

当然了,就其本身而言这并不是问题所在,但是这意味着如果游戏让玩家面临“失败”的境况,这就显得有些残忍和严酷。也就是玩家在游戏中只能够获得胜利——如此便破坏了他们的有意义决策。玩家只能在游戏中缓慢或快速地完成游戏,使得游戏最终失去竞争性。

那么我们该做些什么?

没有人质疑多人游戏中的有意义决策——因为经过证明,这是单人游戏所面临的问题,所以我将针对此类游戏做出解答。首先,任何单人游戏都必须具有随机元素。

首先,如果你的游戏缺少随机性,那就说明游戏拥有一个明确的答案,如此便剥夺了玩家做出有意义决策的权利(就像是我们之前所提到的谜题)。如果你将在游戏中强调任何有意义的决策,那就不可避免地会出现“失败”情况,这时候一些胜利也将不再算数了。

很多人应该知道一种被称为“roguelike”的地牢爬行游戏,这种类型的游戏应该算是单人游戏的最后捍卫者了。网络播客Roguelike Radio最近播出了以“其它类型Roguelike功能”为主题的节目。

我是这个播客的忠实观众,我也希望我们能够在各种类型的单人游戏中看到更多“roguelike”功能的出现。并不是因为roguelike有多出色,而是因为roguelike不会出现诸如“permadeath”(也就是失败)及随机性之类的概念——直到20世纪90年代为止,所有游戏都具有这些特性。

下面我将列出一些包含有意义决策的单人玩家游戏。

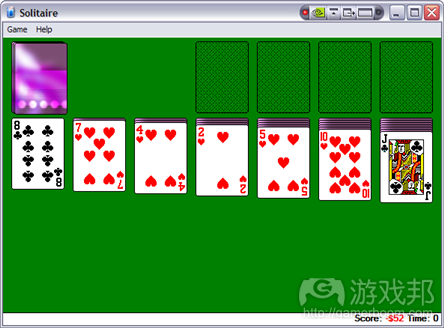

《Klondike》(针对于Windows的单人纸牌游戏,也就是我们常说的“solitaire”)便是一款真正包含有意义决策的单人玩家游戏。我独自玩了这款游戏很长时间,并且在这段时间里我发现自己所做出的选择能够改变游戏今后的挑战,甚至是影响游戏的结果。

最近,Derek Yu所创造的《Spelunky》也添加了有意义的决策,并且它也成为了最有名的一款平台游戏(拥有我所认为的平台游戏应该具有的特性):随机分配的关卡。因为玩家在游戏中面对的是随机出现的关卡,所以即使他们的游戏技能得到加强,他们也不可能知道接下来会出现何种关卡。所以在《Spelunky》中,玩家便能够利用游戏技能帮助自己做出决策。

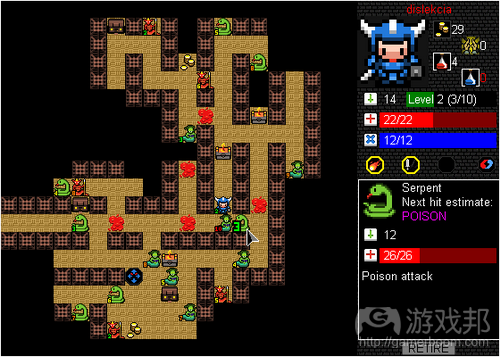

《Desktop Dungeons》不仅拥有有意义的决策,同时它还通过创造性的方法为玩家呈现这些决策。在游戏中,若玩家打败了比自己级别高的怪物便能够获得奖励。所以玩家便可以在游戏初期选择药剂(一般都会被预留下来应付游戏最后的boss)去打败一些中等级别的怪物以获得额外经验值。

这是一种有效的“模糊决策”,因为玩家事先并不知道额外获得的经验值是否值得自己去使用药剂。这也是玩家在其它游戏中从未经历过的,所以他们无法在做决策上获得帮助。不过对于游戏来说却是好事:因为玩家将会想出一些全新的想法,且将动用自己的脑子努力做出最有利的决定。也就是玩家将被迫思考而做出一些全新决策。

认可了有意义决策的重要性后,我们就需要思考如何在游戏中的每个时刻提供更多有趣的、有意义的决策。我将其称为“游戏设计效能”。

尽管《Klondike》拥有一些有意义的决策,但是它也拥有许多无需思考或者说是错误的决策,如此看来它便拥有较低级别的设计效能。而《Spelunky》拥有更高级别的效能,因为游戏具有即时性,使得玩家常常会因为时间限制而不得不快速做出决策,不过游戏中也仍然存在一些无需思考的情况。《Desktop Dungeons》则拥有较高的效能,尽管对于新手来说游戏的很多决策太过简单,但是真正在行的玩家会知道,很多简单的行动通常都不是最佳选择。

还有另一种能够提供有效“模糊决策”的方法(让游戏变得更加特别且有趣):尽管玩家获得了胜利,但游戏依然创造出更多空间,让他能够赢得更多内容,而他却不知道这些内容。在竞赛中,你知道应该在鼹鼠下一次出现时快速敲击它,这里不存在任何模糊性。在谜题中,如果问题被解决了,那就被解决了,不存在其它可能性。尽管你还有其它解决谜题的方法,但是所有解决方法的效果都是相同的。对于游戏来说,如果玩家能够拥有“我想知道如何进行完善”的想法,那才是游戏真正有趣且神奇的地方。如果游戏能够提升玩家探索未知理论的能力,那才是游戏真正的价值所在。

我希望我所提到的这些关于游戏的理论不会被当成一种迂腐的想法,或者禁锢着我们对于游戏的看法。我真心认为完善游戏的最佳方法便是仔细研究如何创造出一款游戏。我发现很多打着研究游戏旗号的人其实都只是在做表面功夫,他们不断地在谈论着“游戏对于不同人来说是不同的内容”诸如此类的无聊观点。

最后我想再次重申,我们应该始终牢记,有一种东西叫作游戏,即使你不同意我的观点,我也希望你能够坚持自己对于游戏的信仰,并专注于制作出最有效能且最有趣的游戏。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

What Makes a Game?

by Keith Burgun

In the beginning, Tetris had a much looser system for random piece (Tetronimo) generation. This meant that when you were playing, you could not be sure of how long it would be until your next line piece would come. This made the decision to “save up for a Tetris, or cash in now” a lot more ambiguous.

Between the new “7-bag” system of piece generation (which puts all seven pieces into a bag and draws them out one at a time, guaranteeing that you will get a line piece every 14 pieces at the latest), the “hold box”, and usually five or six “next” boxes, modern Tetris is largely a matter of execution. Maybe you love what Tetris has become, and think that these changes are purely positive. That’s fine — but I think we can all agree that something has been lost.

The Concept of Games

I propose that games are a specific thing.

What I mean by that is that I think there is a unique concept that I can only call “game”, and this is something different from the large blanket term we use in the digital game world. We video gamers call everything from digital puzzles, interactive fiction, simulators, to even digital crafting tools “games” (or “video games”).

Essentially, anything digital, interactive, and used for amusement gets called a game. And the dictionary will go even further — it calls a game an “amusement or pastime.” So watching TV is a “game.” Hell, eating a can of beans can be a “game” if it amuses you!

The thing is — there exists a special thing, a thing that isn’t a toy, isn’t a puzzle, and isn’t any of those other things I mentioned. It’s a thing that’s been around since the dawn of history, and it still thrives today. We have no other word for it, really, than “game”, so for the purposes of this article, that’s the language I’ll be using. To refer to the larger category of “all digital interactive entertainment”, I’ll use the term “video game.”

I define this thing — a game — as “a system of rules in which agents compete by making ambiguous decisions.” Note that “agents” don’t necessarily have to both be human, one is often the system (as in a single-player game). But the “ambiguous decisions” part is really crucial, and I am here to argue that it’s the single most important aspect in a game.

This is a prescriptive philosophy — a way to look at games that you may not have before — not a description of what exists. In other words, of course there are video games (I prefer to adopt the mobile-gaming term “apps”) that are puzzles that have elements of games, and there are games that have elements of simulators. I’m here to argue that because of this blurring of the word “game” and its inherent qualities, we are somewhat inadvertently losing this meaningful, ambiguous kind of decision, particularly in the area of single-player digital games.

What Makes a Decision Meaningful?

It’s possible that some of us have forgotten how good it is to make an interesting, difficult decision that we can never take back.

Games have a very special kind of decision-making. In a good game, the decisions have the following qualities: they’re interesting, they’re difficult, and the better answer is ambiguous. Above all else, however, the decisions have to be “meaningful”.

I don’t mean “meaningful” as in personal meaning, such as “they make you think about your relationship with your dad” (although they certainly could). By “meaningful”, I simply mean that your decisions have meaning and repercussions inside the game system; they cause new challenges to emerge, and most importantly of all, they have meaning with regards to the final outcome of the game.

Some may be quick to point out that all video games — puzzles, simulators, toys — all involve some form of “decision-making”. That is absolutely true, but nothing else forces the player to make decisions in quite the way that a game does. Any decisions you might make in a puzzle, for instance, are either correct or incorrect, and decisions you make in a simulator do not have a larger contest (context) inside which to become meaningful.

A Hierarchy of Interactive Systems

As I said, a lot of different types of media get bunched up together in a giant bracket we refer to as “video games,” but as I also said, I think we all know that games are also their own unique thing when it comes to any non-digital fields. Employees at Toys R Us have no problem separating their puzzles from their board games, each of which usually get their own separate areas, for instance.

I’ve created a chart that illustrates the relationships between some of the different types of interactive systems that we encounter in the world casually known as “games”:

This image illustrates a proposed hierarchy of interactive systems.

Simulators (Examples: Flight Simulator, Sim City, Dwarf Fortress) — A simulator is a type of interactive system whose primary responsibility it is to simulate something.

In the end, one of the interesting differences between a simulator and a game is that it’s not a valid complaint to say that a simulator isn’t fun. Simulators really have no inherent requirement to be fun — they only need to simulate something.

So, you could have a simulator that simulates something fun and interesting as in Dwarf Fortress, or you could have a plant-growing simulator. It’s worth noting that even in Dwarf Fortress, there’s no guarantee that anything particularly interesting will happen.

I recall one game where my fortress went totally undisturbed, with almost no significant events happening for many hours. Were it a game, I might be disappointed, but given that it’s a simulator, I actually appreciate that this is a real possibility.

To be more precise, the real difference between a simulator and a game is that a simulator is not a type of contest, and a game is. Of course, I suppose you could have a “contest simulator”, but the fact remains that competition is not an inherent part of simulation.

Contests (Examples: a weightlifting contest, Guitar Hero, Simon) — All games are contests, but not all contests are games. The issue is that while contests are competitive, they do not require meaningful decisions. They are often a pure measurement of ability — a simple question of “how much weight can you lift”, or for the example of Guitar Hero or Simon, “how well have you memorized this sequence”. It can be a bit hazy in some situations, but generally I think most of us have a pretty good innate sense of what the difference is between a game and a contest.

One exception to this would be something like Guitar Hero, which I expect that many people would be appalled at the thought that it is a contest, and not a game. Firstly, you should know that calling something “not a game” is not a value judgment, although it’s often mistaken for one. I personally believe that Guitar Hero is a lot more like a contest than a game, because it is a pure measurement of ability, and I would argue that little or no meaningful decisions can be made during play.

Puzzles (Examples: a Portal level, a jigsaw puzzle, a math problem) — A puzzle is another word for “a problem”. A puzzle has a single correct answer — a “solution”.

Some games can also be solved (“perfect information” games, such as chess, where all the information about the game state is known to the player), however if it is common for people to be able to solve a game, it’s considered a knock against that game (Tic-Tac-Toe is solved easily by most people other than very young children, and therefore it is not considered a good game for adults). Puzzles, on the other hand, do not get a knock for having a solution; that’s what they’re all about.

So do puzzles have “decision-making”? I argue that they do not — at least, certainly not at all in the same way that games do. Puzzles are not games, because while some puzzles allow players to make decisions, this is actually rather irrelevant to the outcome. All that matters for a puzzle is whether or not the player gave the correct answer.

If a math problem asks four plus six, if you say 10, you have solved that puzzle. What you did along the way changes nothing about the outcome. So, while you can make decisions while attempting to find the solution, these decisions are actually irrelevant to the puzzle. In games, decisions that are made by the player have effects that change the state of the game, and the outcome of the game. So in games, a player’s decisions really matter in a way that they don’t in puzzles, and this is the way that I draw the line between games and puzzles.

Enemies of the Decision

As I see it, we’ve got three major issues that are most guilty of threatening the meaningful decision in games. These are also examples of problems which would naturally be avoided if game designers adopted my philosophy for games. They are character growth, saved games, and a story-based structure.

Character Growth. Ideally, a game should be increasing in difficulty as a game progresses. However, we’ve now got an expectation that our character — our avatar — will gradually increase in power as the game progresses.

Of course, designers try to make up for this by cranking the late game difficulty further, but this is a very bad position to put yourself in, and it’s one of the reasons why we in video games have such trouble balancing our games.

Essentially, you’re trying to hit a moving target. Assuming that the player can become better at the skill of the game, and the character can also become more powerful, and both of these can happen at somewhat irregular rates, the prospect of balancing late-game difficulty becomes impossible.

Anyone who’s played a Final Fantasy game through to the end can back me up on this (I remember the final boss of Final Fantasy VII being pathetically easy for my Cloud to take down.) I think the designers of such games are aware of this issue and prefer to err on the side of “too easy”.

Of course, if your game is too easy, then your decisions are no longer meaningful (as my decisions weren’t meaningful in my Sephiroth battle — I think it was a foregone conclusion just based on character stats alone).

Saved Games. I call the quicksave/quickload (or any similar system) “the most powerful weapon ever wielded” in a video game. This one is so straightforward that I can keep it short: essentially, a player’s job is to try to play his best; to try to make optimal moves. The game allows you to save and load whenever you want. So, when faced with a difficult decision, what is the logical thing to do? Save the game, then make the decision. Well, looks like that was a bad idea! Re-load the game, and try Door Number Two. Hooray! I’m so good at this game!

The issue with saved games is that they insulate us from ever having to make a meaningful decision, a decision that has effects on the game. If you can reload after making a bad choice, then that choice gets no chance to have effects on the game. If you can save the game right before every challenge, then it is no longer a contest. Once again, it’s a foregone conclusion. It’s only a matter of when you win, not if.

I should mention that there’s a common counter-argument to this argument that goes something like, “well, if you don’t like to reload the game after messing up, don’t do it”. The issue with this is that I am having to create extra rules, “house rules”, if you will. I am having to do part of the game designer’s job, and that isn’t fair. Furthermore, many games are actually balanced with this in mind as an element of gameplay, and due to my next item, it’s actually rather unavoidable…

Story-Based Structure. Never before video games was there this idea that games get “completed”. Instead, games were played in “a match”. Now, all games are expected to have a long campaign, capped off by a credits reel. This completion-based mindset has dire effects on our friend, the Meaningful Decision.

Firstly, most story-based games are quite long, with regards to games from throughout history. While most games historically have taken between ten minutes and a couple hours to finish a match, modern video games aren’t considered “finished” in any sense of the word for twenty or more hours.

This on its own isn’t a problem, but it also means that it becomes a bit cruel and harsh to actually ever give a player a meaningful “loss” condition. So, that means all that they can do is win — therefore the meaningfulness of their decisions is destroyed. All they can do is beat the game slower or faster; it’s no longer a competition.

What, Then, Should We Be Doing?

Again, nobody’s having issues with meaningful decisions in multiplayer games — it’s single player games that are proving to be the issue here, so that’s what I’ll be addressing. Firstly, for any single-player game, you simply have to have random elements.

If your game doesn’t have randomness, then it has a correct answer, and if it has a correct answer, then there really aren’t meaningful decisions for a player to make (it more closely resembles a puzzle as described above). Further, if you care about having any meaningful decisions, then “losing” has to exist in some form, and having several flavors of winning doesn’t count!

Many of you who know about the dungeon-crawling genre known as “roguelikes” might know that they are one of the last defenders of this sort of play in a single-player game. The internet podcast Roguelike Radio recently had a show topic called “Roguelike Features in Other Genres” (listen to this episode here).

I was a guest on this episode, and I predicted that we were going to start seeing more and more quote-unquote “roguelike” features in all genres of single-player games. Not because of how great roguelikes are, but because roguelikes don’t actually own concepts like “permadeath” (which really just means, losing) and randomization at all — up until the 1990s, all games had these qualities.

Here’s a few examples of single-player games that do, in my view, have meaningful decisions.

Klondike (the solitaire card game that came with Windows, which we often just refer to as “solitaire”) is a solid example of a single-player game that has real meaningful decisions. I’ve been playing the game a long time myself, and while it might not be clear to some who’ve only played a handful of games, I notice these moments where I have a real choice that changes the future challenges and even the outcome of the game.

More recently, Derek Yu’s Spelunky ran with this concept, literally, and became one of the first well-known platformers to do what I’ve always thought platformers should be doing: randomizing the levels. Because the levels are random each time you play, becoming good at Spelunky has absolutely nothing to do with memorization or any kind of “process of elimination”. It has to do with your skill at making decisions in Spelunky.

Desktop Dungeons is not only a game with meaningful decisions, but it does so in a brilliantly innovative way. In the game, you gain bonus experience for defeating a monster that’s higher level than yourself. So, you can choose to use potions early-game (usually reserved for the end-game boss) in order to defeat some mid-level monsters to get that extra experience.

It’s a great example of an “ambiguous decision” — you don’t know for certain if the spent potion will be worth the extra experience or not. No level of experience playing other games will have really helped you make this decision, either. This is what’s so exciting about games: the idea that when someone comes up with a game that’s really new, it actually exercises your brain in new ways. It forces you to make new kinds of decisions that work in a way that your brain never had to work before.

If we can agree that meaningful decisions are important, then we can hone in, focus our games down on offering as many interesting, meaningful decisions as possible per moment spent playing the game. I call this “efficiency in game design”.

While Klondike does have some meaningful decisions, it has many no-brainers, or false decisions — so I’d say it has a rather low level of efficiency in this way. Spelunky’s a bit higher, since it’s real time and you’re actually threatened most of the time, but there are still some situations that are no-brainers. Desktop Dungeons is highly efficient, and while it may seem to newcomers that there are no-brainers, better players realize that the most obvious moves are rarely the best ones.

And here’s another way to look at the whole “ambiguous decision” thing — this is what makes games special and interesting: even when you won, there was always room for you to have won by more, and you’re not sure how. In contests, you always know how — hit the moles even faster when they appear next time. There’s no ambiguity about what you should be doing. In puzzles, if it’s solved, it’s solved. There may be different ways to solve the puzzle, but all solutions are equal. This feeling of “I wonder how I could improve” is what’s so magical and amazing about games. In a way, games ask us to rise to our unknown theoretical highest level of ability, and this is really valuable.

I propose this philosophy about games not to be pedantic or controlling about how we look at games. It is my sincere belief that the only way we can really improve our games is by looking closely at what makes a game a game. I don’t see many people really doing this; instead I see a lot of people simply echoing safe but conversationally useless ideas like “games are different things to different people”.

Again, I propose that we remember that there is a thing called game, and even if you don’t agree with my ideas, I hope that you do pursue your own truth about what games are, so that you can focus your games into the most efficient, fun games they can possibly be. To quote the author Robert McKee in his book Story, “We need a rediscovery of the underlying tenets of our art, the guiding principles that liberatetalent.” (source:GAMASUTRA)

上一篇:现代迷你游戏模式缺乏构思统一性