用户社区管理是MMO游戏成败的关键

作者:Simon Ludgate

MMO游戏的特别之处在于?其他玩家,存在众多其他玩家,由其他玩家构成的完整社区。虽然我曾半开玩笑表示,其他玩家是MMO游戏存在的最大问题,但这也是它们的最大资产——-有些人甚至觉得这是它们的唯一可取之处。玩家为什么要每月付费反复体验同款游戏,接触相同内容?因为他们能够同其他真实玩家一起体验游戏。

我一直觉得MMO游戏的最重要功能是创建强大玩家社区。你的游戏多么光彩照人或内容多么丰富多彩无关紧要:若游戏缺乏社区,那么玩家就会选择离开。社区是决定一款MMO成败的关键:一鸣惊人且备受好评的游戏若无法创建稳固社区,最终也会以失败告终;而有些游戏虽然颇为乏味,但由于玩家高度投入,如今依然处在运作中。

越来越多公司开始认识到社区管理的重要性。他们聘请社区管理员,终日潜伏在官方论坛同玩家进行互动;他们创建游戏内部机制方便玩家进行更有意义的互动;他们设计能够凝聚玩家而非隔离他们的游戏内容。

但不是所有公司都采用这一新型运作模式,我多次看到众多游戏因“营销”或“平衡”决策分离玩家而最终以失败收场。

当代警示案例

类似情况不久前出现在Square Enix工作室(2012年2月9日)。《最终幻想XI》的MMORPG续作《最终幻想XIV》自发行以来持续面临糟糕设计决策及单调内容等问题,这些令玩家颇为失望。但游戏坚持采用免费试验模式,因此保持稳固的玩家社区(游戏邦注:在去年12月采用订阅模式前游戏约有1.2万的同步登陆用户)。

基于这一情况,Square Enix任命新制作人,并声称公司将扭转乾坤。随后公司开始收取月订阅费用,尽管此时距离再次发行时间已有1年多。这让公司得以剔除那些忠诚度不高的用户,且没有致使玩家社区分崩离析,因为《最终幻想》的忠实付费用户继续体验游戏,期盼他们的未订阅好友有天能够返回。

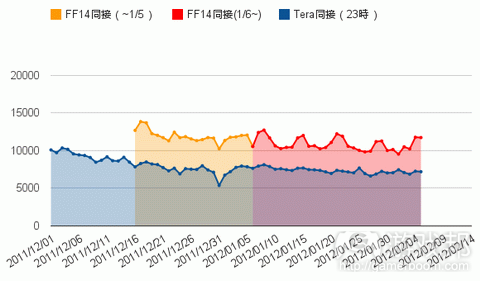

(注意:此用户数据图表是基于玩家自己的预测。橘色是预先订阅用户,红色是后期订阅用户。除非Square Enix能够提供与此相左的数据,否则在我看来这些数据还是相当准确的)

换而言之,尽管游戏存有问题,但强大游戏社区支撑游戏顺利运作,Square Enix的回应则是“我们未来会让游戏重新运转,请继续支持我们。”

这令公司最近发布的消息令人颇为困惑。Square Enix宣布《FFXIV》将进行服务器兼并,但不是传统意义上的“二合一”模式。相反,其原计划是消除之前所有的服务器,要求玩家在10个新服务器中进行选择,这不是针对所有玩家。只有活跃订阅者需要选择搭载服务器。其他玩家则会被随机重新安置。

换而言之,Square Enix想要重组自己剩下的用户,通过这个过程,将不活跃的玩家同他们之前的游戏好友隔离开。他们还将删除所有Linkshell(公会),清理所有好友列表(以及黑名单)。

游戏将提示当前订阅用户,他们的非付费好友会远离他们。而当前非订阅用户将发现,自己无法继续同好友共同体验。两个群体因此都颇为沮丧,因为同好友共同体验是MMO的特点所在。

庆幸的是,《最终幻想XIV》的主要制作人Naoki Yoshida很快撤销他们的原始公告。原始官方公告因此被废止,虽然我们依然可以看到完整公告内容。这个问题依然处在持续发展中,无疑会进一步扩展,但这个事例是本文话题的最佳例证:

若你想要让玩家付费体验自己的大型多人在线游戏,你得允许玩家同好友共同体验。

《Rift》的失误之处

你可以通过很多方式阻止玩家一起玩游戏。最显而易见且最有效的方式就是将他们转移至不同的服务器,不要让他们看见彼此。但我们还可以通过其他方式阻止他们进行共同体验,这些情况甚至出现在那些出自善意开发商之手的作品中。

以《Rift》为例,这是Trion的首款MMORPG游戏。Trion非常注重发展稳固社区,从普通的“制作人信件”反馈到更个性化的GM介入方式,旨在推动游戏中的玩家情谊。Trion还积极促进玩家同好友共同体验游戏。其Ascend-a-Friend参考项目除发送免费版本外,还自动在彼此的好友列表中添加推荐人和被推荐人,让他们能够进行信息传输。但就如MMORPG.com的Isabelle Parsley所指出的,这无法真正促使他们共同玩游戏,因为新玩家处在关卡1,而多数推荐玩家都已经处在关卡50。

我在邀请好友玩《Rift》的时候曾遇到这个问题。当时我处在关卡50,操作的是关卡50的内容,而他则处在关卡1,所以我另外创造新角色陪伴他。

这个方式运作得非常顺利,但有时他会在我操作关卡50内容时登陆游戏,然后超越我的替换角色,所以我就只得升级我的替换角色,重新赶上他,直到他的等级越来越高,足以匹敌我的另一角色,然后我再次同他进行合作。

总之,他最后没玩到关卡50就放弃游戏,因为他无法“真正”同我共同体验。

《Rift》还尝试另一未能顺利在其他游戏中落实的策略:免费试验关卡上限。《魔兽世界》流失近20%的订阅用户,尽管它免费呈现前20个关卡的内容。《战锤Online》玩家纷纷取消订阅,转而选择免费试验内容,因为这里是PVP操作内容的集中区域。《乐高宇宙》不得不暂停游戏,因为他们发现自己无法由免费试验模式转移至订阅模式。

免费试验关卡上限存在的问题是什么?它未能让玩家共同体验游戏。从技术角度看,这一设置允许玩家相互照面,订阅玩家可以创造低关卡替代角色同免费试验玩家共同体验。但实际情况是,多数订阅用户所处的关卡都超过免费试验关卡上限,他们没有任何动机,更别说机会同低关卡好友共同玩游戏。免费试验玩家其实就是在玩单人游戏,游戏还询问他们是否愿意付费订阅此单人游戏。这显然行不通。

玩家共同体验的障碍

我们完全能够秉承“促使玩家共同体验”的理念设计游戏。这里最主要的是克服隔离障碍:阻碍玩家共同体验的因素。隔离障碍有两种:操作障碍和设计障碍。操作障碍是指涉及游戏操作的游戏元素,不受玩家游戏体验的影响。订阅费用就是操作障碍之一;分散于不同服务器也属于这种类型。

消除多重服务器或允许玩家自由在服务器中切换是克服这类障碍的典型范例。收取服务器切换费用或不支持服务器切换则将不利于克服这类障碍。这是因为在玩家来看,操作障碍通常阻碍他们实现游戏目标。

设计障碍则更为棘手:他们是隔离玩家的游戏要素。这些要素通常颇吸引玩家眼球(游戏邦注:例如关卡,因为这赋予玩家成就感,能够让玩家觉得自己步入新阶段)。需获得足够工具,方能在富有挑战性的突袭中对抗boss是设计障碍的典型例子;玩家需处在适当探索阶段,方能进入特定副本也属于这种类型。

但设计障碍也会受到游戏设计师的影响:例如,允许玩家“建立师徒关系”、“变成伙伴”或“实现关卡同步”的游戏能够顺利克服各关卡玩家所遇到的障碍,轻松获得的“welfare epics”允许游戏提供足够工具,让玩家在完成较低层次的突袭后进入较高等级的突袭操作中。

不要误解我的意思。我并没有推崇welfare epics。我只是赞同能够让高级玩家重返低级关卡的游戏设置,例如《Rift》的每周突袭任务,鼓励高级玩家“重返”早期突袭任务,让较弱玩家能够接触到这类内容,从中获得若干道具。这里所说的是解决设计隔离障碍的合理(刺激因素)及不合理方式(工具发送)。

但这些方式并不总是具有可行性。玩家一周只能接触一项突袭任务,从而防止他们获得过多战利品,这意味着他们无法重返游戏,帮助好友完成关卡任务,即便他们愿意放弃获得更多战利品的机会。若要鼓励玩家共同体验游戏,那么封锁突袭任务是另一我们需要反思的设计障碍。若你的首要目标是让原本对突袭战利品不感兴趣的玩家参与制突袭操作中,那么这点就非常重要。游戏为什么要提供特殊刺激因素,促使高端玩家参与至低端突袭操作中,然后又在一个回合后将他们排除在这一区域之外呢?

同样,能够聚集玩家,将其送至副本的自动副本探测器(游戏邦注:常出现在《魔兽世界》或《Rift》之类的游戏中)应克服社交障碍,真正将玩家聚集起来。但这类机制带给社区创建带来的影响并不牢靠。

有时,设计和操作障碍的差异性会模糊化,例如Turbine的《Dungeons & Dragons Online》。在《DDO》采用免费模式时,其加锁众多游戏探索区域,这些区域只有付费用户能够接触,这就属于操作障碍。

但Turbine还允许购买探索区域的付费用户或订阅用户购买贵宾关口,从而让未购买此探索内容的用户陪伴他们共同体验。

这有效克服操作障碍,但带来设计障碍:什么刺激因素可促使玩家向陌生玩家发送贵宾关口?什么促使玩家选择付费副本内容,而不是免费内容?

《DDO》的贵宾关口是允许玩家共同体验的范例,但若是允许玩家部分时候共同体验怎么样呢?“允许”(let)是必要条件;“促使”(get)提高玩家满足感、转换率、留存率及带来资金收益的关键。但下面还几点建议:

操作障碍总体来说属于消极元素。没有玩家希望自己因操作设置而同好友分离。尽可能降低操作障碍应该是开发者的首要着眼点。

免费“循环内容”从某种程度上说就是遵循这一理念,其去除最显著的操作障碍:订阅费用。但订阅费用无需废止,只要你的产品能够向消费者(游戏邦注:包括那些暂时放弃订阅的用户)提供有价值的内容,能够有效回避操作障碍。

设计障碍通常来说属于积极元素。它们让玩家获得成就感,这通常是玩家在游戏中积极实现的主要目标。其问题出现在当这类元素阻碍玩家共同体验的时候。

克服这些障碍有两个常见解决方案:让玩家跳过障碍的援助方式,这个方式不大受欢迎,特别是对那些着眼于通过克服这些障碍收获成就感的玩家而言;再来就是奖励返回已操作内容玩家的“贿赂”方式,这种方式更普遍,若运用得当,这能够促使游戏形成持久社交社区,而这是造就稳固游戏的首要条件。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Tearing Down Barriers: How to Bring MMO Players Together

by Simon Ludgate

What makes MMOs special? Other players. Lots of other players. Whole communities of other players. While I may semi-seriously joke about other players being the biggest problem in MMOs, they’re also the genre’s greatest asset — some might say even say their only redeeming feature. Why pay a monthly fee to play the same game, experience the same content, over and over, week after week? Because you’re doing it with other real people.

I’ve long held that the most important feature in any MMO is to build a strong player community. It doesn’t matter how shiny or content-filled your game is: if it lacks in community, players will leave. Community makes or breaks an MMO: games that have leapt off the starting block full of praise and high review scores fell flat on their faces when they failed to build strong player communities, and games so bland they ought never have been made in the first place are still running today thanks to player involvement.

More and more companies are recognizing the importance of community management. They hire community managers to lurk on official forums all day and interact with players; they build in-game systems to help players interact more easily and more meaningfully; they design content that drives players together rather than apart.

But not every company is on board with the new way of doing things, and time and time again I see games fall apart because “marketing” or “balance” decisions have driven players apart.

A Contemporary Cautionary Tale

One such bombshell was lobbed out of Square Enix’s office last Thursday (Feb 9, 2012). Final Fantasy XIV, its MMORPG sequel to the successful Final Fantasy XI, has struggled since launch with poor design choices and lack of content that upset many players. Nevertheless, the game kept running on indefinite free trial and retained a strong community of hopefuls (about 12,000 simultaneous logins just before subscriptions started in December of last year).

Based on this, Square Enix appointed a new producer, and swore it would turn things around. Then it started charging a monthly fee, despite the fact that the announced re-launch was more than a year away. Granted, that turned away the less dedicated fans, but it didn’t completely tear the community apart, as the Final Fantasy faithful paid up and kept playing, hoping their unsubscribed friends would one day return.

(Caveat: This graph of player population numbers is based on player-generated estimates. Orange is pre-subs, red is post-subs. However, unless Square Enix wants to provide data showing the contrary, I assume these numbers are pretty accurate.)

In other words, despite the problems with the game, the strong game community kept things going, and Square Enix’s response has largely been “We’ll get it working for you; stick with us until then.”

This makes the company’s most recent announcement all the more confusing. Square Enix announced server mergers for FFXIV, but not the normal “two into one” procedure most gamers are familiar with. Instead, its original plan called for the elimination of all the previous servers, forcing all players pick one of 10 new servers to move to. Well, not all players. Only active subscribers get to pick where they go. The rest will be relocated randomly.

In other words, Square Enix was looking to completely shake up the remaining population and, in the process, isolate any lapsed players from their prior in-game friends. They were also going to delete every Linkshell (guild) and wipe every friends list (and blacklist) clean.

Current subscribers were being told their non-paying friends are being taken away from them. Current non-subscribers were being told they were barred from sticking with their friends. Both groups are upset, and rightly so, because playing with friends is what makes MMOs so special.

Thankfully, the lead producer for Final Fantasy XIV, Naoki Yoshida, rapidly backtracked on the original announcement. The original official announcement was taken down, though it can still be read in its entirety here. The issue is still ongoing, and will doubtlessly develop further, but the recent event is a prime example of what I want to discuss in this article:

If you’re going to get people paying for your massively multiplayer online game, you have to LET them play together.

What Rift is Getting Wrong

There are many ways you can prevent your players from playing together. The most obvious and brute-force way is to send them all to different servers and never let them see each other again. But there are other ways to prevent players from playing together, ways that permeate even the games made by the most well-meaning of developers.

Take, for example, Rift, Trion’s first MMORPG. Trion has a strong community focus, ranging from the usual “letter from the producer” feedback to more personalized GM interventions to promote in-game camaraderie. Trion also works hard to get people playing with their friends. Its Ascend-a-Friend referral program, in addition to handing out a free trial, also automatically adds referrer and referee to each others’ friends lists, making it easier to find each other in-game, and giving them the ability to teleport to one another. But as Isabelle Parsley of MMORPG.com points out, this doesn’t actually let them play together, because new players start at level 1 and most referring players are at level 50.

I experienced this when I invited a friend to play Rift. I was level 50, doing 50 stuff, and he was starting out at 1, so I made a new character to accompany him.

And it was going well, but sometimes he’d log in while I was in the middle of 50 stuff, and he’d level up ahead of my alt, so I’d have to level up my alt to get caught back up again, until he got so far ahead of my alt I just waited until he leveled up enough to catch up to another one of my alts, which then kind of teamed up with him again for a bit…

Long story short, he quit before he got to 50, since he never “really” got to play with me.

Rift is also trying another tactic that hasn’t worked well in other games: the capped level endless trial. World of Warcraft lost nearly 20 percent of its subscribers despite implementing an endless free trial up to level 20. Warhammer Online saw players cancelling their subscriptions to play in the free trial because that was where all the PVP action was. And Lego Universe had to shut down when it found it was unable to convert free trial users into subscribers.

The problem with level capped free trials? It doesn’t let people play together. Oh, sure, it technically allows them to cross paths, and subscribers could technically make low-level alts to play with free trial players. But the reality is that most subscribers are going to be higher level than the free trial level cap and they’ll never have any incentive, let alone opportunity, to play with them. Left on their own, free trial players are basically playing a single player game, and then asked if they want to sign up for a subscription to this single player game. It won’t work. It can’t.

Barriers to Letting Players Get Together

It is possible to design a game with “letting players play together” in mind. The most important issue is to overcome segregation barriers: the factors that completely prevent players from playing together. There are two kinds of segregation barriers: operational barriers and design barriers. Operational barriers refer to elements of the game that concern the game’s operation and are largely unaffected by a player’s game experience. A subscription fee is an example of an operational barrier; so is being on different servers.

Eliminating multiple servers (ala EVE Online) or allowing players to freely transfer from one server to another (ala Rift) are good examples of overcoming that barrier. Charging a fee for a server transfer or denying server transfers at all is a bad way of overcoming that barrier. This is because the operating barrier is often perceived by players in opposition to their goals.

Design barriers are trickier: they’re elements of the game that separate players. These are often desirable elements in a game, such as levels, because they give players a sense of accomplishment, of going someplace they couldn’t before. Getting enough gear to be able to face the bosses in a challenging raid is an example of a design barrier. So is being on the right stage of an epic quest to enter a particular dungeon.

But design barriers are also being challenged by game designers: games that offer players the ability to “mentor” “sidekick” or “level sync” overcomes the barrier presented to players of different levels, for example, and easily obtainable “welfare epics” allow games to distribute enough gear to get players into higher tier raids after lower tier raids have been abandoned.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not exactly in favor of welfare epics. I actually prefer ways to get better geared players back into lower tier instances, such as Rift’s weekly raid quests that encourage even the best end-game players to “pug” (pick-up group) the earlier raids, giving less intense players a chance to see that content and get some gear. Again, this points to good ways (motivations) versus bad ways (gear handouts) to solve a design segregation barrier.

But these systems don’t always work. Players are locked to only one raid instance a week to prevent them from getting too much loot, but this means they can’t go back and help friends complete the instance, even if they were willing to be locked out of getting more loot. Raid lockouts are another design barrier that might need some rethinking if players are to be encouraged to play together. This is especially important if your goal is to get people who aren’t interested in a raid’s loot into the raid in the first place. Why offer a special incentive to get high-end raiders into low-end raids, then lock them out of the zone after one run?

Likewise, the automatic dungeon finders that group people and teleport them into a dungeon, featured in games like WoW and Rift, were supposed to overcome social barriers to actually forming groups with players. But the effect systems like these have on building communities is questionable, at best.

Sometimes, the differentiation between design and operational barriers blur, such as in Turbine’s Dungeons & Dragons Online. When DDO went free-to-play, it locked many of the game’s adventure areas as premium pay-only content, an operational barrier.

But Turbine also allowed paying users who had bought the adventure area, or who were paying for a subscription, to buy guest passes, allowing users who did not buy that adventure to accompany that player inside.

This overcame an operational barrier, but it left a design barrier in its place: what motivation was there for a player to hand out guest passes to strangers? What motivation was there to do that dungeon at all, rather than a free one?

DDO’s guest passes are an example of letting players play together, but what about the getting them to play together part? The “let” is a necessary first step; the “get” is the key to customer satisfaction, conversion, retention, and all that monetary goodness. But here are a few bits of advice to get everyone started:

Operational barriers are generally a Bad Thing. No one likes to be shut out from their friends because of some arbitrary operational setting a producer in a dark, dank cell decided on. Reducing operational barriers as much as possible should be a primary focus.

The free-to-play “revolution” sort of embraces this idea, by tearing down the most obvious of operational barriers: the subscription fee. But the subscription fee doesn’t have to go, so long as the product you sell provides good value to all its customers — including those who opt out of subscribing for a period — and avoids other operational barriers.

Design barriers are generally a Good Thing. They let players feel a sense of accomplishment and are often the main goals players work towards overcoming in games. The problem is when they get in the way of players playing together.

There are two general ways of overcoming these barriers: the leg-up approach of letting players bypass the barriers, which is generally an unpopular approach, especially among those players who worked hard for the satisfaction of overcoming them legitimately; and the bribery approach of paying off players to go back down to that stuff they had done before, which is generally popular and, if well implemented, encourages building those lasting social community bonds that are so integral to building a strong game in the first place.(Source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号