现代游戏可考虑借鉴老式游戏的静音方式

作者:Leigh Alexander

与许多老式冒险游戏狂热者一样,我对LucasArts在1990年发布的游戏《LOOM》印象深刻。尽管LucasArts发布的所有冒险游戏都受到人们的喜爱,但《LOOM》的粉丝似乎显得特别狂热。或许,部分原因是因为其粉丝数量较少,部分原因是因为它相对于当时其他游戏而言更为新潮。

这款梦幻般的游戏的背景是个布满各种行会的世界,包括牧羊人、铁匠、玻璃工人和纺织工,每个行业的人都有独特的魔法能力。玩家扮演的是年轻的纺织工Bobbin Threadbare,他必须努力解开纺织公会消失之谜,在这段经历中面临重重威胁。

在游戏中,音乐和音效扮演着很重要的角色。玩家像使用乐器那样用Bobbin的拉线杆来使用魔法,学习四音节曲调,可以当作简单的咒语,有些咒语适合在某些特定背景下使用。倒序演奏曲调往往能够产生相反的效果,游戏解谜的乐趣就来源于以创新的方式来前后播放曲调施放咒语。

游戏的音轨来自于柴可夫斯基的芭蕾舞剧《天鹅湖》,故事讲述的是公主受到诅咒变成天鹅。这在主题上与游戏想适合,因为所有Bobbin的同伴都在被转变成天鹅后消失了。精心编排的音乐很符合《LOOM》中布满星光的世界、田园般的土地和布满玻璃的王国。对于许多在当时刚刚接触电脑的游戏玩家而言(游戏邦注:包括作者在内),正是这款游戏让我们接触到了经典交响曲。

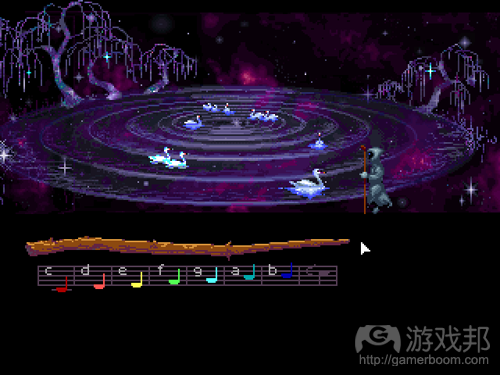

在游戏世界的构建中,《LOOM》还精心使用了色彩。Bobbin拉线杆上的音符有着各种颜色,演奏或环境对象触发咒语时会发出漂亮的光芒。场景中,不同说话人的文本会使用不同的颜色。在游戏最高级的模式中,区分音符的字母消失,当学习咒语时玩家接触的完全是颜色和音效,就像《LOOM》的游戏玩法完全依赖于倾听音乐一般。

如此结合的整体效果是产生出独特的体验,让人享受到优雅和充满美学的乐趣。我上周末在Stream上购买《LOOM》,正是希望能够再次体验到这种静谧的感觉。可是,我不知道该游戏已经重新设计,购买的下载版中包含了配音。我的第一个念头就是:为何要在如此漂亮且令人深思的游戏世界中加上配音呢?

随后,我又提出新的问题:如果没有配音的话,有多少游戏会变得更好呢?

我记得小时候玩过《Turbo Grafx 16》,我很喜欢游戏玩法暂停时音乐淡出的效果,这样我就知道角色准备要开始说话了。有时,他们的嘴唇甚至会移动,而且我喜欢游戏中卡通化的配音,似乎给这两个不同的世界增添更多现实感。

孩提时代,这种简单的现实主义做法似乎可以接受,我会认为这是出于技术上的限制,而不是开发者做出的美学选择。当然,随着技术的发展,让角色变得更栩栩如生、音乐变得更丰富、文字变成声音,这确实是更有意义的做法。对于那些早期的电脑游戏来说,“更栩栩如生”是其唯一追求的目标。

我认为从那以后,我们就知道“更现实主义”对电子游戏来说并非总是优化元素。还记得那些带有真实演员的PC游戏吗?今天我们会嘲笑这些游戏的做法,因为增添真实演员会突显游戏同电影和电视间的差异。

我们习惯了欣赏持续时间很长的CG过场动画,全动态影像甚至成了RPG的卖点。但是现在,多数RPG粉丝偏爱老式游戏,那时保持沉默的手绘图像和安静角色会激发我们丰富的想象力。

但是,当游戏设计师最终意识到过场动画属于非互动行为,篇幅过长有悖于互动娱乐的形式和功能,于是全配音角色就成了普遍做法。但是,我却渐渐感觉到自己更青睐可阅读型游戏、安静的游戏和无声的角色。

在像我这样的老游戏玩家中,怀旧的人依然很多,这种趋势逐渐明显。我常常觉得,那些被我们所抛弃的老式游戏中有值得学习的地方。虽然,许多现代游戏有丰富和优秀的配音,但我认为需要更多地探索如何使用静音。当你不能播放声音时,就必须在交流方式发挥更多创意。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Enjoy the silence: On voice acting in games

Leigh Alexander

Like many old-school adventure game aficionados, I have fond memories of LucasArts’ 1990 title LOOM. Though the entire slate of LucasArts adventures is deservedly well-loved, LOOM seems to enjoy an especially passionate fanbase, probably in part because it’s much less-known, and in part because of how unconventional the game is relative to others of its time.

The fantasy game is set in a world of guilds — shepherds, blacksmiths, glassmakers, weavers — each with a unique magical gift related to their discipline. The player is cast as the young weaver Bobbin Threadbare, who must unravel the mystery of his vanished guild of Weavers and of his own origin, and his journey gets him wrapped up in a larger threat to the “fabric” of reality itself.

Music and sound play a powerful role in the game. Players use magic by playing on Bobbin’s distaff like an instrument, learning four-note tunes that act as simple spells (e.g. “opening”) that have unique, context-appropriate applications. And playing the tunes backward often reverses the effect, and the fun in the game’s puzzles comes from thinking both forward and backward about spells you discover in creative ways.

The game takes its soundtrack from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake ballet, the story of a princess cursed to transform into a swan — which is thematically appropriate, given that all of Bobbin’s fellow Weavers disappeared after being mysteriously transformed into swans. The elegant arrangement of the music well suits LOOM’s world of starlit islands, pastoral fields, kingdoms of glass and palaces of stone. For many a young computer gamer, myself included, the game was among the earliest introductions we had to classic symphony.

LOOM also makes fine use of color, beyond the palette of the game world. The notes on Bobbin’s distaff are color coded and sparkle prettily when played or when an environment object glimmers clues to a spell. Different shades of text are used to differentiate multiple speakers in a scene. In the game’s most advanced mode, the letters that identify the notes disappear, and color and sound are all players are given when learning spells, as if the purest form of LOOM’s gameplay is about putting ears to music alone.

The overall result is a sonorous, cerebral experience, elegant and aesthetically pleasant. It was this kind of quiet mystery I was hoping to rediscover when I bought LOOM on Steam over the weekend for a replay. Little did I know that there’d been some kind of remastered version made, and that my newly-purchased download included voice acting. My first thought: Why in the world would you muck up such a beautiful, thoughtful game with voice acting?

And then, I wondered: How many games are, or would be, better without voice acting?

I remember having a Turbo Grafx 16 with a CD drive as a young girl, and getting excited about the pause in gameplay, the fade-out in music that preceded a disc-read squee that let me know that characters were about to speak. Sometimes their animated mouths even moved, and the cartoonish voice acting in games I loved, like Ys I & II, seemed to lend a new note of reality to the two dimensional world.

As a kid, certain shortcomings in realism — whether it was funny-looking textures, limited animation, text-only characters — all seemed like something I had to accept as a technical limitation, rather than something the developers elected as an aesthetic choice. Of course it made sense that characters became more lifelike, that music became richer, that text became voice, as technology began to permit. “More lifelike” was really the only goal those young computer games had, as there wasn’t yet this vision that games were made to do things other media couldn’t.

I think since then, we’ve learned that “more realism” isn’t always an enhancement to video games. Sometimes that lesson manifests itself in obvious ways — remember that weird phase PC games had with all the live actors? We laugh about that today, because adding live actors so starkly highlighted how different games are from film and television, and how some elements just shouldn’t cross over.

There are other examples: We used to get quite excited about long CG cutscenes, thanks to the novelty of seeing games do things we’d never known them to be able to do before. Full motion video was even a selling point for RPGs, a genre that up til then could only offer its players tiny sprites. These days, though, most RPG aficionados prefer the old school, times when lovingly-handcrafted pixels and silent protagonists left so much quiet space in which our young imaginations could bloom.

But while game designers eventually realized that extended periods of non-interactivity, as in cutscenes, betray the form and function of interactive entertainment, fully-voiced characters have become the norm. Increasingly, though, I find myself gravitating toward readable games, quiet games and voiceless heroes.

It’s not so unusual for longtime gamers like me to wax nostalgic for games of old, and that tendency can make it easy to dismiss a lot of that longing as the stubborn thinking of a cranky old-timer, who resists the onward march of technology. But I often feel as if there is much to value in what we left behind. While doubtless many modern games are enriched by (good) voice acting, there is, I believe, still much to discover in the silences. When you hold your tongue, you’re forced to get creative with your communication. I wonder what games could rediscover — or reinvent — if more of them were unvoiced? (Source: Gamasutra)

下一篇:关于游戏&书籍创造性比较的思考

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号