列举现代游戏设计应遵循的10项基本法则

作者:Joe Martin

我发现最近几年,有些原本属于核心设计理念的原则已经淡出了设计师的视野,而正是这些原则开创了之前的游戏黄金时代。

法则1:设置可忽略的过场动画

在我看来,这是最重要的游戏设计法则。几乎每款游戏都不乏过场动画,只是形式有所不同罢了。例如《命令与征服》中Kane喋喋不休的话语,《虚幻竞技场3》(以下简称UT3)开场时的赞助logo,不管怎样,最好将这些设置为可跳过的内容。

开发者通常喜欢设置不可忽略的过场动画——毕竟制作这些内容费了许多功夫,他们希望用户不要错过这些精彩环节。他们认为玩家应该喜欢这种东西,但事实并非如此。

并非所有玩家都会关注与游戏故事情节相关的内容,所以是否设置为可跳过选项,很可能决定他们是继续探索下一关还是直接放弃游戏。另外,假如你不幸搞砸了一场boss战斗,不得不重返原来的保存点从头再来,于是又得再反复观看同个过场动画。这种情况确实很不妙,所以我认为对现代游戏来说,可忽略的过场动画设计远比故事情节更重要。

正例:新版《波斯王子》适当地体现了这个原则,它的过场动画不多,但初玩游戏时你得看完过场动画才能知晓故事情节,而第二次玩游戏时,就可以选择跳过这种内容,玩家只有在特定节点才需要保存游戏。

反例:《Black》这款Xbox游戏视觉效果很出色,尽管玩法上有些小瑕疵等问题,但真正破坏游戏体验的罪魁祸首却是不可忽略的过场动画,这让玩家备感受挫和抓狂。这种动作游戏与冗长而不可忽略的过场动画真不是一种理想的组合。

法则2:避免漏洞等问题

不少人对游戏补丁感情复杂,又爱又恨。一方面,这些补丁可以为游戏增加更多新功能和模式(游戏邦注:例如《原罪前传》中的Arena Mode),但另一方面,补丁也是游戏未完工的体现。我们可以接受一些无关紧要的补丁和较小的漏洞修复,但却无法容忍关键性的更新调整。

无论如何都不可让游戏出现致命的漏洞问题,在开发阶段就要测试妥当并优化游戏,使其成为可合理运行的内容。

但也有些例外情况,尤其是RPG游戏。虽说玩家确实有点难以取悦,但也未必都喜欢小题大作,我们可以宽容对待《上古卷轴4:湮灭》或KOTOR中的一些任务所出现的问题,毕竟有些游戏规模太大了,难以保证其中不出现一点纰漏。

正例:今天我们已经难以找到哪些完全不需要补丁的游戏了,但我认为Steam平台在这一点上的服务十分到位。它至少可确保其平台上所有游戏都保持更新。

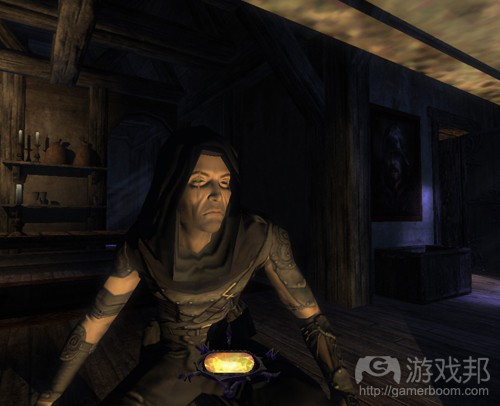

反例:《沸点》、《Vampire: The Masquerade》……有太多游戏都是在尚不具备可玩性的状态下匆匆露面,我无法一一列举,但我认为表现最糟者当属《哥特王朝3》。这款游戏最后一个本简直漏洞百出,有许多技能完全无法使用。虽然它现在已经解决了这些问题,但我却再也不愿意再重新玩这款游戏了。

法则3:要清晰传递目标和信息

如果抛弃其他琐碎的内容,游戏就只剩下一个简单的理念——玩家(无论多人还是单人)只是为了赢得奖励而迫使自己参与激烈挑战并完成一系列目标。虽然这个定义并非无懈可击,但我还是认为游戏最起码要告诉玩家“如果你打败了最后一个boss,就可以得到一些很棒的东西。可能是一个大爆炸也可能是一些罕见的东西”。

优秀的游戏通常都会采用这种做法,而劣质游戏却不会透露这么多信息,它们只会让玩家盲目向前闯,让我们自己瞎摸找出路。

遗憾的是,我们看到即使是那些没有明确规定胜利条件的游戏(例如《模拟人生》),传递的目标都比《黑暗》等射击游戏更明确,而后者却总让玩家卡在半途中不知所措。

所以,开发者最好向《模拟人生》取经,即使游戏有部分目标要求玩家自行探索,也要多少透露一点信息,不要设置让玩家完全自我摸索的目标界面。

正例:《半条命2》就是这种明确传递目标的典型。该系列的整体目标仍然不失神秘性,游戏中的即时与长期目标可以通过多种形式体现出来。

玩家刚进入游戏时就会看到G-Man正在唤醒Gordon,他开始四处张望。随后屏幕立即出现许多视觉提示内容,例如隐隐若见的Citadel和Combine宣传系统,这样整个游戏目标就很明朗了。

反例:《雷神之锤》的怀旧和复古风格备受青睐,但从设计角度来看,其游戏目标和故事的处理手法过于杂乱无章。以最后一个不知所谓的boss为例,它不会主动攻击或者回应玩家,它只会像一个场景道具那样坐在屋子中间看着玩家对付大批的Shamblers和蜘蛛女。我们不知道它就是游戏最后一个boss,而且也没有任何信息提示我们如何杀死它,我也是偶然才发现要用传送杀的方式让它丧命。

法则4:兼顾不同玩家水平设置难度

平衡游戏难度是一个棘手问题,需耗费大量时间才能完善这项工作,若游戏难度平衡恰到好处,就会极大提升整体游戏体验。

《光晕》系列就是一个完美典型。对某些人来说,Master Chief的历险环节只是画蛇添足的一笔,而其他人可能会认为《光晕》真是现代游戏的杰作,它将史诗般的故事和壮观的战役场景融为一体。但相信多数人都会认同一点:这款游戏能够满足多种玩家类型的需求。

有些玩家希望体验优质而简单,并且含有多人模式的掌机第一人称射击(以下简称FPS)游戏,有些玩家却觉得挑战高难度任务才够刺激,他们都能在这款游戏中各取所需。

但随着现代技术的发展,不少开发者似乎已逐渐脱离原来的FPS游戏原型,但这个原则并不仅限于FPS,它适用于所有游戏类型。原版《毁灭战士》提供了广泛的技能级别选择,《雷神之锤》甚至还提供了一个适当隐藏的Nightmare额外难度等级。

与《半条命2》这种游戏相比,它们之间的区别很明显——《半条命2》只有三个难度等级设置,并且这三者之间差别不大。唯一不同的是,敌人在不同难度设置中的死亡速度和杀伤力有所变化。对于一个资深FPS玩家来说,他们在其中躲过敌人的射击并非难事,游戏中的“困难”与“标准”设置几乎难分彼此。

正例:《原罪前传》和《Thief》这两者都是恰当平衡游戏难度的典范,它们分别采用了可应对不同难度设置的AI,在更高难度中添加了额外游戏目标,但我最喜欢的还是《英雄萨姆》。

从最简单的Tourist(游戏邦注:该难度设置可让玩家自动恢复命值)到最困难的Mental(玩家在其中极易受到攻击,弹药有限,并且所有敌人都处不可视状态),《英雄萨姆》提供了适用于多种技能水平的难度设置。

反例:从许多关卡来看,《生化奇兵》可以看是一个杰作,但较致命的是Vita-Life这个区域支持玩家自动复活。这种设置看起来与难度大小无关,而更像是考验玩家的毅力和耐力。

法则5:多人/单人模式并非必需选项

我曾有很长一段时间对多人游戏模式并不感兴趣,我初次迷上电脑游戏时,并不是很在乎自己在《街霸》或《刀魂》中能不能打败弟弟—–我更喜欢战胜电脑系统的那种感觉。

20多年来我仍然喜欢玩游戏,但现在却常沉浸于多人模式的乐趣中,例如每月都会与一些伙伴在《托尼霍克滑板》中相聚,几乎每天都会在《军团要塞2》中与他人组队玩游戏。

在最近几年,多人游戏模式发展迅速,尽管多数时候这种设置更像是一种事后再补充的内容,但似乎已成为现代游戏的必备选项。多人模式本身并无过错,它也确实更能丰富玩家的游戏体验。但问题在于,不可因添加多人模式而损害原来的单人模式游戏体验。开发者资源有限,却还要在游戏中添加吃力不讨好的多人模式,这种情况已经是屡见不鲜。

今天采用多人模式的游戏比比皆是,但有些游戏中的多人模式(例如《凯恩与林奇》)却真的不算成功。所以开发者还是量入为出为妙,《军团要塞2》这种多人游戏未必是大势所趋,除非你有多余的时间和精力,不然最好不要多此一举。

反之亦然,多人游戏也未必要硬塞入单人模式。

正例:《The Ship》是一款由Simon Hill所设计的游戏,它将多人与单人模式分为独立的单位。如果你想玩多人模式,那就购买多人版本;如果想玩单人模式,那就买单人版本。虽然这种将游戏模式一分为二的做法也并不高明,但至少可分别为两种不同的玩家创造最优良的游戏体验。

反例:UT3只是草草添加了一个单人模式,它的问题也在于,其单人模式本身算是一个很棒的新手教程或打发时间的玩物,但它单薄的故事情节等问题,反倒让人觉得与其和bot打斗,还不如不要玩单人模式。

法则6:遵循一定的惯例或传统

我们时常将一些游戏惯例和传统视为理所当然的现象,因为它们自电脑及电子游戏诞生之日起便已存在其中。这包括有意增强游戏体验的设置(例如在文字冒险游戏中输入“N”而非“Go North”代表“向北行进”),以及那些不知起因的设计(例如在平台游戏中踩跳敌人的头部使其毙命)。

不管怎样,这些惯例并不损害游戏操作和体验。我们习惯看到敌人倒下时掉落出一些健康包,或者将板条箱等元素视为关卡结构中的重要组成部分。

当然也有一些游所遵循的惯例并没有给游戏带来多大益处,不过总体上来说,玩家并不会因为游戏总是让敌人站在火药桶旁边,或者自己不能同时持有火炬和枪支而愤怒。

这种趋势在玩家游戏体验中扮演重要角色,让游戏更具通俗性和易用性,这样玩家无需绞尽脑汁思考如果不踩扁怪物的头部,究竟要怎样才能杀敌。但有许多电子游戏却不知何因极力回避这些传统标准,从而破坏了整体游戏体验。

正例:几乎所有表现尚可的FPS都遵从了这个法则,如果非要列举典型当推《毁灭战士》。因为这款游戏中采用了大量的传统元素,例如随处分布的箱子,每个转角处的火药桶以及保护命值的装备和盔甲。这些元素都很符合游戏情境。

反例:《Thief: The Dark Age》颠覆了半数游戏传统,移除了最具攻击力的武器,限制了玩家的自愈能力。玩家不能直接走过拾取道具,而要真的伸手才能拾取,这个过程会制造更多动静,从而让玩家身陷险境。

法则7:清晰易懂的界面设计

游戏界面是个神奇的元素,如果设计得当,就可以提供所有足以让玩家沉浸游戏的信息和元素。但不幸的是,也有些游戏的HUD非常不招人待见,甚至让人觉得“有碍观瞻”。

体面的游戏界面应该具有简洁明了的呈现方式,不可充斥过多繁琐的点缀内容(有些人可能会认为,这些点缀可以更好地塑造游戏情感氛围,例如将数字颜色设置为霓虹绿,添加一些电路板的图像以便游戏更具科幻色彩)。

事实上,这些点缀会干扰玩家注意力。有时候为HUD添加情境元素确实会给游戏增色(游戏邦注:例如《半条命》中的HEV防护衣),但它并不总是必要之物。实际上HUD并不一定需要植入玩家命值倒计时的数字符号,或者当玩家命值降低时进行模糊化的视觉处理,最重要的是应根据游戏整体需求来设计界面系统,不可让界面成为玩家体验游戏的障碍。

正例:《猴岛2:勒恰克复仇记》是该系列首款采用图像显示库存道具的游戏,它使用SCUMM引擎使这款指向点击游戏妙趣横生。它根本无需用户手册或新手教程,因为整个系统的标识都很明朗。点击“打开”和“门”,就可以直接开门。

如果觉得这个过程很复杂,玩家还可以右击鼠标执行特定任务以节省时间,这样可让游戏界面更具易操作性。

反例:《Nethack》是一款Roguelike游戏,它似乎有意设计了一个看起来很古老笨拙的复古界面。它的ASCII呈现方式和复杂的游戏规则设置已经让新手颇为费解,这种界面则更像是考验玩家对游戏控制方式的记忆力,极少人能够通关就很能说明问题。

法则8:不要采用全动态影像(Full Motion Vudeo,即游戏的片头、过场和片尾的动态画面,以下简称FMV)

我实在想不出有哪款能够有效处理FMV元素的游戏。虽然有些游戏已经使用FMV成功扩展故事情节,而且拥有不错的演员和故事写手等资源来制作具有可看性的视频内容,例如《幽灵的国度》。即便如此,这种FMV仍然存在缺点,《幽灵的国度》就用了6张CD才能容纳这些冗长的过场动画。

关键问题在于,设计师通常需要与能够了解游戏媒介、演技过硬的演员配合,才能制作出可行的FMV,这可是件高难度的差事。多数好莱坞演员都没接触过游戏FMV,而多数玩家能够明显看出开发者所赋予的角色个性,演员表现的人物特点,以及玩家自身体会之间的区别。

唯一能够创造出接近于可行性FMV的游戏当属《命令与征服》系列,尤其是拥有大量演员亮相的最后一幕。但就算是这样,整个游戏体验还是因其累赘的FMV,以及沉默不语的主角而大打折扣。

正例:任何不推崇FMV的游戏都在此列,幸好这是当今的主流形势。

反例:任何充斥大量FMV的游戏(这在90年代早期尤为盛行),《Phantasmorgia》和《狩魔猎人2》的表现最为典型。要制作一款含大量FMV环节的冒险游戏并非可行做法,当你预算不足并且只有蹩脚演员之时更是如此。

法则9:提供便捷的保存设置

当然也有一些例外情况,但前提是这种保存系统能够在保证可行性的同时,通过具有沉浸感的妙招植入游戏中(例如《生化危机》中的打字机存盘方式)。最好是允许玩家在任何时间都能保存、加载游戏,并且便捷使用快速保存操作。

设置自动存档点并无过错,但问题在于它的设置区域不对——例如,在大型激战半途中突然自动保存,帧速率骤然降低了好几秒,让你总是通过自动加载回到之前丧命前两秒的地方。

这个法则与法则1关系紧密,因为它会涉及到在不可忽略的过场动画前进行自动保存的问题。设置不可跳过的环节已是不妥做法,在错误的地方进行保存同样不可取。而如果一款游戏兼具不可跳过的情节/过场动画,以及迫使玩家在特定节点保存游戏(例如过场动画之前)更是让低劣的游戏体验雪上加霜。即便是世界上最优秀的游戏,只要它强迫玩家连续看20遍关于boss战役的介绍,相信大家都会纠结不已。

正例:《喋血街头2》尽管遭到非议,但至少在保存系统这个方面具有优势。它的保存系统很简单,玩家可以在进入新区域的任何时间保存游戏,也可以根据自己的需要快速保存。这一点并无特别出彩之处,值得称道的是如果玩家经常采取快速保存操作,游戏中的主角就会谴责玩家,这真是一种幽默的设计。

反例:《光晕3》的保存系统很糟糕,不管你有多喜欢这款游戏,都不得不承认即便是以掌机游戏标准来看,它在这个方面的表现真的很不如意。它没有快速保存和加载选项。如果你不想重复操作,就得确保每次都先“保存”并“退出”游戏。

法则10:敢于打破常规

不得不承认,真正出众的经典游戏都是那些勇于打破规,并且能够融合一般游戏标准以创造更多兴奋感的作品。

我们难以定义伟大游戏的标准,但我认为这些游戏之所以能够脱颖而出,很大程度上要归功于其设计师敢为人先的创新勇气。

《传送门》常因其美术、音效、关卡设计和游戏机制之间的完美融合而备受赞誉。但对我们来说,它的出众之处并非关卡或机制,而是用悖于常理的方式将一系列怪异的主题合为一体。

《传送门》是一款从第一人称视角体验的解谜游戏,它将玩家禁锢于一个狭小的空间,只给他们一件武器,但同时又给他们创造了许多行动自由。它是一款恐怖游戏,不断制造不祥的低吟,同时又有不失轻松搞笑的幽默感。它是两个角色之间的冲突,但其中一者却根本不会出声。它是射击游戏,但玩家若非自杀就绝对不会丧命,另外它还有一个巧妙的结局。

总之,《传送门》证明常规就是用来让人来打破的。

正例:除了《传送门》,另一款值得一提的游戏是《Garry’s Mod》,它几乎没有任何目标,它起初定位是《半条命2》的修正版,现在则是Steam平台的一款平价游戏。

《Garry’s Mod》的特别之处并非易用性或功能,而是魄力。它的界面很复杂而难以驾驶,设置了宏大而空旷的关卡,玩家要是吃透了复杂的界面就算是从游戏中得到了收获。尽管如此,它还是极具娱乐性,值得玩家投入精力。

反例:对许多人来说,《毁灭战士3》真是让人大失所望,这主要归咎于其平庸的游戏设计。

它使用了太多传统惯例,充斥大量弹药桶、板条箱和令人作呕的僵尸。与此同时,它的HUD过于呆板,而重复性的设计也导致玩家难以驾驶游戏环境。它的故事平淡无奇,而冗长的战役则让游戏更像是一桩苦差事。

游戏邦注:原文发表于2008年1月23日,所涉事件及数据以当时为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Rules of Game Design

by Joe Martin

One of the new features we’ve launched lately on bit-tech has been guest columns. That is, columns written by developers and industry insiders on a rotating monthly schedule. We’ve had stories and thoughts from every corner of the industry, including budding indie developers like James Silva and writers for established studios, like Simon Hall and Rob Yescombe.

After reading Simon Hill’s latest column, which talked about difficulty balancing in computer games and why he thinks computer games have got progressively easier, I got thinking. The more I thought about the topic, the more I decided I wanted to do something about it – partly because I’m a pretty heavy gamer and I like my games to be worth the effort, but mainly because I’m just a nosey busy-body.

As I looked into the issue though, the more my mind raged with examples of how games had changed for the worse over the years – how simple concepts that had once been core to the design of every game were now being forgotten or dismissed. The rules that had governed and created the Golden Axe Age of Gaming were now no longer being obeyed.

Naturally, being a bit of presumptuous so-and-so, I decided to shove my nose in and take Simon’s complaint to the next level. Thus, I present what I think are the cardinal rules of game design.

The first rule of game design isn’t ‘don’t talk about game design’, it’s…

Call of Cthulu is an example of a game which had unskippable cutscenes

Rule 1: No unskippable cutscenes

This is the first and most important rule of designing a game in my opinion. Nearly every game has cutscenes in some way, shape or form. It can be as long and tedious as one of Kane’s rambling speeches in Command and Conquer or it can be as simple as the sponsorship logos at the start of UT3. Either way, they should be skippable. No exceptions.

It can be very tempting for a developer to make a cutscene unskippable – after all, it took ages to make and it’s a great way to showcase the fantastic story, right? Players want to see it!

No, we don’t.

Not all gamers are as pretentious as me and some of them just don’t care about narrative and plot twists, so the option to skip a cutscene can be the difference between reaching Level 10 and giving up at the introduction for some player. Plus, if you mess up a boss fight and have to go back to a previous save point then you’ll end up watching the same cutscenes over and over. Oh, joy. So, that’s it – the first thing we demand of modern games is that they have cutscenes that can be skipped over if we decide the story isn’t worth it.

The new Prince of Persia games had an inventive way of managing cutscenes

Rule Obeyer: The new Prince of Persia series found a nice way around this little rule, and I think that deserves a mention. The game has a fair few cutscenes spliced through it and the first time you play the game you have to watch it in order to understand the story. The second time you watch though the game remembers that you’ve already seen it and lets you skip right on through, which is handy because you can only save the game at certain checkpoints.

Rule Breaker: Black – this Xbox title was beautiful to look at, despite the somewhat flawed gameplay and the breathtaking brevity of the whole thing. Still, what really ruined it for many was the unskippable cutscenes which had players hammering buttons from the start in frustration. If nothing else though, it mindless action games and long, unskippable cutscenes don’t really go together all that well.

Rule 2: Make the game work

Patches – at bit-tech we both love them and hate them. On the one hand, they can add in new features and game modes like the Arena Mode in SiN: Episode s but, on the other hand, they are symptomatic of an unfinished game at the same time. Some patches and minor fixes we can tolerate. Critical updates, we can’t.

Games shouldn’t need critical patches really anyway – they should be tested and proven to work from the offset. This was another topic which Simon tackled in a column about the process of testing and quality assurance, highlighting how segregation of testers and developers is just one of the many problems facing bugfinders.

There are exceptions to this rule though, especially in the RPG genre. We gamers are pretty demanding, but we don’t want to take the mick, so if a few quests are a tad broken in Oblivion or KOTOR then we can accept that. Some games are just too massive to be completely bug-free.

However, there is a level of brokenness that it’s impossible to forgive and games with bugs like corrupting savegames and system reformats should be hunted down, shot and gutted. And then patched back together so the process can be restarted.

Rule Obeyer: It’s depressingly hard to think of games which don’t need patches nowadays, but I suppose if there was one good guy in the bunch then it’d be Steam. Not technically a game, true, but the system does at least mean that all games attached to the platform remain perfectly up-to-date – for better and worse.

Vampire The Masquerade may have been a great game, but it took dozens of patches to get it that way

Rule Breaker: Gee, where to begin? Boiling Point? Vampire: The Masquerade? So many games are released in broken, unplayable states that it’s hard to keep track. Worst of them all though was probably Gothic 3. The final release was nought but a myriad maze of bugs with enemies appearing as floating black boxes and skills not working properly. Apparently the game is now in a workable state but personally, I haven’t been bothered enough to go back and check.

Rule 3: Communicate goals clearly and immediately

There’s nothing more infuriating to me than an objectives menu in a game and this rule stems from that hate.

Games are a simple enough concept when all the chaff is thrown away – players, whether single or multiple, participate in a competitive activity that challenges them to complete a series of goals in exchange for a reward. This definition is probably a bit flawed as far as Merriam-Webster is concerned, but it’ll do for now; basically a game tells a player “If you defeat the last boss then I’ll show you something cool. Probably a big explosion or some barely-covered boobies, m’kay?”

Or at least, that’s what the good games do. Bad games don’t dish out all that information, forcing us to plow on blindly, hitting all the brick walls until we find the door.

It’s a very sad state of affairs when we see games that don’t have defined victory scenarios, like The Sims, having goals that are more clearly communicated than those in a shooter like The Darkness, which has players dumped into weirdly twisted landscapes halfway through the game.

The Sims didn’t even have an aim, but at least it communicated that clearly!

So, developers, the lesson is thus; Learn from The Sims and, even if you have a part of the game where the goal is to explore the area, tell us that somehow. And don’t do it through an objective screen that we have to access ourselves – it just defeats the point.

Rule Obeyer: Half-Life 2 is a classic example of how goals can communicated without ramming them down a player’s throat. While the overall goal of the series is still a mystery thanks to the enigmatic G-Man, immediate and game-long goals are given to the player through a variety of means.

The very first thing players see is the G-Man encouraging Gordon to wake up and look around. Immediately after there’s a plethora of visual clues, like the looming Citadel and Combine propaganda – these make the overall goals clear. From the very start of the game every player knows one thing; that skyscraper is coming down one way or another.

Rule Breaker: Quake may be untouchable in terms of nostalgia and retro appeal, but as far as game design goes it seems it was very much a case of throwing ideas at a wall and seeing what stuck.

Unfortunately, the one thing which didn’t stick was the aim of the game and the story itself. Take the unexplained last boss for example, Shub-Niggurath. This blob like beast can’t attack or react to players at all, so it just sits in the middle of the room like a piece of scenery while players fend off dozens of Shamblers and spider women. With no clue that the blob is actually the end-game boss and no clue how to kill it, it’s no wonder I only figured it how to telefrag it by accident.

Rule 4: Difficulty should cover all abilities

This rule stems directly from my original inspiration, Simon’s column about game difficulty. You can call it plagiarism if you want, but it’s a valid point so we think it should be included no matter.

Difficulty levels in games are tricky things to balance and can take absolutely ages to perfect, but when a game is properly balanced then it shines through as if the whole game had been given a mirror polish. Turning speeds, firing rates, build times – these little tweaks can make or break a game.

The perfect example is the Halo series. To some, the adventures of Master Chief are derivative and lacklustre at best, while to others the game is a modern masterpiece that blends an epic story with a gloriously smooth campaign. What very few people disagree on though is that the game caters for all niches of the gamer market.

Those who want a nice, easy console FPS that they can run through on multiplayer are catered for just as adequately as those who want to slog through on Legendary difficulty.

BioShock’s vita chambers made the game more a case of perseverance than skill… some loved it, others hated it.

As technology has progressed, it seems as if developers have moved away somewhat from the original prototype of FPS gaming, though the rule is applicable to all genres. The original Doom games had a wide selection of skill levels, while Quake even had the extra Nightmare difficulty which was very well hidden.

Compare that to a game like Half-Life 2 and the difference is obvious – Half-Life 2 has only three difficulty settings and none of them make much difference. The only things which seem to be changed, and I have completed the game on all three settings, is how easily enemies die and how much damage they do. To an experienced FPS player though, dodging enemy fire isn’t all that difficult and Hard is indistinguishable from Normal.

Rule Obeyer: While Sin: Episodes and Thief are games which excellently balance themselves by using adaptive A.I and extra objectives at higher difficulties respectively, Serious Sam is still my favourite.

Essentially one big arena battle after another, Serious Sam catered for all skill levels by having lots of settings ranging from one extreme to the other. At one end there’s the Tourist difficulty where health automatically regenerates, while at the other is the Mental setting – which makes you easier to hurt, limits your ammo and makes all the enemies invisible. That’s rough stuff, obviously.

Rule Breaker: BioShock may have been a masterpiece on many levels, but the one thing that ruined it was the Vita-Life chambers that automatically revive the player. With these in place it doesn’t matter how hard the game is, the experience just becomes a matter of persistence and endurance.

Rule 5: Multiplayer isn’t always required

Multiplayer gaming is something that I personally wasn’t interested in for the longest time. When I was first getting into computer games quite heavily, I didn’t particularly care about being able to defeat my brother in Street Fighter or Soul Calibur – to me it was more interesting to prove that I was faster than a computer.

Fast forward things two decades and I’m still into my games, but multiplayer is now massively important to me. Between monthly throw-downs on Tony Hawk’s Underground 2 with some chums and almost daily matches of Team Fortress 2, multiplayer has become massively important to me. So important in fact that a few years ago I even made the long pilgrimage from the numpad to a WASD configuration.

Multiplayer has taken off massively in the last few years and, although it was once an added bonus to games—tacked on almost as an afterthought—it now seems obligatory for modern games. That’s fine in itself; gamers are all the better for it. Where it gets a problem though is when the multiplayer side is added on to the detriment of the singleplayer mode. Developers have only a limited amount of resources at their disposal and to redirect those resources into a multiplayer mode that will never take off at the expense of an extra singleplayer level is something we see too much.

Call of Duty 4′s multiplayer is incredibly popular, but there’s not room for lots of mediocre multiplayers.

Multiplayer games are a dime a dozen nowadays and, while some games like Call of Duty are an exception, its mostly very unlikely that the multiplayer side of a game like Kane and Lynch will prove successful enough to merit the effort. Face it guys, nothing is going to be Team Fortress 2 for a long time, so don’t bother unless you have extra time on your hands or something legitimate to add.

Oh, and this rule works both ways too – multiplayer games don’t need tacked on singleplayer modes.

Rule Obeyer: The Ship was a game designed by guest columnist Simon Hill, and shows just how multiplayer and singleplayer should be done – as totally separate entities. If you want to play the multiplayer version, you buy the multiplayer version. If you want to play the singleplayer, you buy the singleplayer. Dividing the two into different games isn’t where the genius lies though, that’s in the fact that Outerlight worked on one at a time to create the best experience possible for each.

Rule Breaker: Unreal Tournament 3 mixes it up by just tacking on an awful singleplayer mode, but it’s the same idea. The singleplayer segment itself is great as a tutorial for newcomers or a timewaster, but the flimsy storyline and plot workings mean that the game could have possibly done better without it – either way you just end up fighting bots.

Rule 6: Conceits are OK

There are plenty of conceits and conventions in game design, many of which we don’t even pick up on because they’ve been built into computer and video games since time out of mind. They range from those that have been deliberately created to enhance a game experience, like typing ‘N’ instead of ‘Go North’ in text adventures, to those that have come out of nowhere, like jumping on a bad guy’s head in a platform game.

Either way, contrary to public opinion, these conceits are OK in gaming. It’s all right to have enemies who drop health packs when they die, or to make use of crates and flaming barrels as an important part of a level structure. Really.

There are games that take the conventions too far for too little benefit, true, but by and large there’s really no reason for gamers to become agitated at a single game just because it has baddies who stand next to explosive barrels or because you can’t hold a torch and a gun at the same time.

These trends are an important part of how players experience a game, making it familiar and accessible while ensuring that there’s no need to spend ages figuring out how to kill a monster if you don’t jump on its head. Too many video games try to avoid these standard conceits without good reason, ruining them in the process.

Rule Obeyer: Almost all half-decent FPS games could take the honourable mention here, but if pushed we’d probably have to give it to Doom simply because it started a lot of them. There were boxes everywhere, explosive barrels at every turn and the health kits and armour all looked the business. Who cares if the main character doesn’t actually wear a glowing green helmet – it works within the context of the game!

The Thief series has thrived on being out of the ordinary

Rule Breaker: Thief: The Dark Age turned half of these gaming conceits on its head, removing most offensive weapons from the game and limiting the player’s ability to heal themselves. You no longer just ran over items to pick them up either, you had to actually reach out and take them, creating noise in the process and putting yourself at risk. It was a first person shooter, just with the shooter bit taken off and trimmed back. It was also bloody marvellous.

Rule 7: The interface should not be a problem

Game interfaces can be fabulous things. When they work well, they supply you with all the information you need to forget the real world even exists and you can slide into the game like a greased slug slipping into a vat of Vaseline and oil – i.e. smoothly.

Unfortunately, for every game with a good interface there’s a game with a HUD so clunky and rigid that it feels like a hammer in your eye socket – i.e. painful.

A decent game interface should be clean and simply presented, without all the faff and chaff that some people seem to think sets a good mood for the game. That mood usually involves making the numbers neon green and surrounded with pictures of tiny circuit boards in the vague hope that the game feels more Sci-Fi.

In reality, all those things do is distract gamers. OK, so sometimes a context for a HUD (like the HEV suit in Half-Life) is a nice addition, but it isn’t always needed. In reality, it doesn’t matter if the HUD involves a numerical countdown of player health or blurry vision that kicks in when health gets low – what is important is that the game is built with this system in mind and that the interface doesn’t become a barrier.

Adventure games like Sam and Max are the best example of how an interface should work

Rule Obeyer: The Secret of Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge was the first game in the series to use images for inventory items on all formats, combining that with the SCUMM engine to make a point and click game that was a joy to use. There’s no need for a manual or tutorial at all because the whole system is so clearly labelled and the system is so refined. Click Open, click the Door and, hey presto, you’ll open the door.

If that’s too complex, you can always use the right mouse button to perform the highlighted obvious action to save time, making the interface even easier to use.

Rule Breaker: Nethack is a game that falls into the Roguelike genre and therefore has a retro interface which is deliberately designed to be archaic and unwieldy. With an ASCII presentation and a complex set of game rules already making the game pretty hard to grasp for new players, the interface is just the icing on the cake. Memorising the controls is one of the key skills needed in the game, so the fact that so few people have finished it really speaks for itself.

Rule 8: FMVs are always a bad idea

I can’t think of a single game ever which managed to use full motion videos in a helpful, correct way. I can think of games which use FMVs to advance the plot successfully and have decent enough actors and writers on hand to make the videos worth watching, such as Realms of the Haunting, but even then , the FMVs have drawbacks. Realms spanned a massive six CDs in order to accommodate the lengthy cutscenes.

The main problem seems to be that in order to create a workable FMV, designers need to work with actors who understand their medium and the players need to be able to see a relationship between the actor and the in-game character. Such things are incredibly hard to do. Most Hollywood actors won’t touch game FMVs and most players draw a distinction between the personality developers give a character, the way the actor plays it and the way the player views it.

The only games that even come close to creating a workable FMV format is the Command and Conquer series, especially the latest entry which has a number of decent actors on board. Even then though the experience is tainted by our experience of past FMV-laden games and the use of a silent protagonist makes the whole thing feel vaguely suspect and annoying.

There’s only one man who can do FMVs properly…

Rule Obeyers: Pretty much any game which doesn’t feature FMV, which nowadays is the majority, thankfully.

Rule Breakers: Any of the FMV-filled games that became fads in the early nineties. Phantasmorgia and Gabriel Knight 2: The Beast Within stand out especially, but for all the wrong reasons. Trying to build an adventure game completely out of FMV segments really doesn’t work, especially when you’ve got awful actors and a low budget.

Rule 9: Saving should not be a chore

There are some exceptions to this rule, but unless the saving system can be feasibly put into the game in a way that is immersive and reasonable – like the type writers in the Resident Evil series, then we’d prefer it if most games just had the usual setup. Save at any time, load at any time and use quicksaving to make it all easier.

There’s nothing especially wrong with checkpoints and the like, but too often we see them placed stupidly – autosaves in the middle of a massive battle, bringing the framerate to a crawl for several precious seconds and ensuring you’ll always autoload to a point exactly two seconds before you die.

We’re sorry to all you fanboys, but Halo 3 had an awful save system

This rule also ties in with Rule #1 in regards to saving before an unskippable cutscene. Having parts of the game which can’t be skipped is one thing. Having a game that saves in the wrong place is another thing too. Having a game with sequences and cutscenes which can’t be bypassed and also forcing players to save at specific points, i.e. right before the cutscene, is a recipe for unprecedented disaster. It could be the best game in the world, but if we have to watch the intro to a boss battle twenty times in a row then even we start to get annoyed.

Rule Obeyer: Postal 2 for all its awfulness and controversy for controversies sake, did one thing well – the save system. It was simple. The game saved whenever you moved to a new area and, on top of that, you could save and quicksave as much as you want. Nothing special in that alone perhaps, but having the (very) vocal main character insult you for constant quicksaving gave it a nicely humorous touch.

Rule Breaker: Halo 3 had an awful save system and, no matter how much you liked the game, you have to admit that in this regard it was bad even by console standards. There’s no option to quicksave or load – no chance to save at all. Instead, if you want to avoid repeat performances, you’ll have to ensure you Save and Quit every time. If that’s not a pain in the backside of hellish proportions, I don’t know what is.

Rule 10: Break the rules

For all our lecturing and posturing, we have to admit that the games that really stand out as classics for us are those that aren’t afraid to break the rules and mix up the usual trends of gaming in favour of something a little more exciting.

What exactly makes a great game is hard to define but a big part of what sets a great game apart from simply a good game is when designers have the guts and drive to rend our expectations apart.

Portal is often overly cited as an example of excellence in game design for the way the art, sound, level design and game mechanics pull together. To us though, it isn’t the crazy levels or deliberately mechanic voices which make it such an awesome experience – it’s the way it goes against common sense and fuses a bizarre set of themes and topics together.

Portal is a puzzle game played from a first-person perspective which massively confines players to very small areas while giving them a single weapon that provides more freedom of movement than you’d think was possible. It’s a scary game with constantly sinister undertones, but it’s a laugh-a-minute at the same time. It’s all about the conflict between two characters, one of whom can’t or won’t talk at all. It’s a shooter where you can’t die unless you suicide and, to top it all off, it’s got a big musical finale.

Portal ticked all our boxes, but broke all our rules

In short, Portal shouldn’t work at all because it breaks pretty much every guideline. Somehow though, it also became our Game of The Year.

It just goes to show – sometimes rules are made to be broken.

Rule Obeyer: Excluding Portal, we’d probably have to say Garry’s Mod. Completely lacking in any aim whatsoever, Garry’s Mod started out as a modification for Half-Life 2, but it’s now a fantastic budget game available on Steam.

GMod, as it is affectionately known to regular players, is a game which thrives not on accessibility or capability, but on ambition. It has an interface that’s complex and hard to navigate, levels which are normally vast and empty and a game design that means the only reward lies in actually understanding the complex interface. Again though, it’s also massively entertaining and totally worth the effort.

Oh, look! It’s yet another dark room with a monster in it!

Rule Breaker: Doom 3 was, to many, nothing but a massive disappointment and the core of that lay in the uninspired game design. Doom 3, for all the technological prowess it possessed, may as well have been Paint by numbers with John Carmack and Co.

The game used standard conceits far too much and the sheer number of barrels, crates and zombies was nauseating even though the whole game was shrouded in a perpetual inky blackness. At the same time, the HUD felt slightly bulky and cumbersome and the environments were hard to navigate thanks to repetitive design. Throw that in with a story penned by a very unimaginative dog and an incredibly long campaign which made the whole thing a chore and it’s no surprise that most of us skipped straight to the Cyberdemon. (source:bit-tech)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号