从欧洲游戏看主题对游戏项目的重要性

作者:Mike Compton

作为一名游戏设计师,我最近有了一些新的领悟,主要是关于主题的重要性。我想有必要先谈谈“什么是真正‘优秀的’游戏”?在我的游戏评估标准中涉及了6大领域,包括:

-清晰

-流畅

-平衡

-深度

-综合

-乐趣

很多游戏都只停留在早期开发阶段,甚至难以成为一款“成熟”的好游戏。它们还处于“不够完善但具有绝佳潜力的待完善”阶段。然而,即使经过完善,很多游戏设计也仍只能停留在“平庸”阶段。的确,我们面临的首个挑战是拯救一款级别较低的游戏,但是很多游戏设计师却很难真正提高他们的游戏级别(其中也包括我自己)。这是为什么?

在这里我想以Adam Smith的观点进行分析。在撰写《国富论》之前,Smith曾经写了一本名为《道德情操论》的书。他在书中的一些声明也适用于我们的讨论话题:

“在所有精心雕琢且充满自由的艺术中,包括绘画,诗歌,音乐,修辞,哲学等,真正优秀的艺术家总会觉得自己的作品不甚完美,并且比起其他人,他们更加清楚最后的结果与他们心中完美的概念差了多少,而当他们越是仿照着这一概念努力,结果却越会让他们感到失望。只有低级的艺术家才容易自我满足,他不知道何为完美,也不会去实践自己的想法;他们只会模仿其他艺术家的作品,甚至是一些更低级别的作品。”

创造出一部真正伟大的作品需要投入许多精力,同时也需要很多时间。同时,为了达到一些更高级别,我们就需要听取一些严厉的批评,并且不要想着如何为自己辩解,而是应该从中获得学习。同时我们还必须拥有一整套客观的评价标准,并用于衡量我们接收到的任何批评,以此才能让我们的游戏免受某些平庸之才的玷污。

我最近的领悟主要是关于欧洲游戏主题的发展,以及我们之中有多少人在主题发展方面有所“懈怠”。我们总是轻易地满足于某些低于正常水平的主题。这关系到我的游戏设计标准中的“综合性”范畴,但我们所需处理的问题却并不仅局限于将游戏的各个子部分整合在一起。首先,我们先来说说为何主题如此重要,以及为何我们中的许多人出现了“主题懈怠”的情况。

从潜在发行商,制造商以及游戏玩家的角度来看,他们之所以愿意选择你的游戏肯定是有理由的。他们都需要问自己“为何我要尝试这个人的游戏?”而对于许多游戏设计师来说,他们内心中对于这个问题总是只有一个明确的答案:

“我设计了这款游戏,这不就是最好的原因?我将这款游戏从一个襁褓婴儿培育到现在,可想而知在我心中它有多优秀。”

不幸的是,除了那些“什么都说好的人”,如你的亲戚或朋友(游戏邦注:他们可能只会提供给你的游戏设计正面的肯定而不是一些中肯有意义的反馈),那些根据自己的标准选择游戏的人根本不吃这一套,他们不会轻易花时间去听你炫耀游戏,更加不会轻易坐下来尝试你的游戏。

游戏设计师必须掌握换位思考的重要性,即懂得如何从不同的角度去看待游戏设计,而不再只是以自己立场看待问题。所以,一款游戏能够吸引玩家的“理由”到底是什么?

我们必须始终牢记,游戏机制是一种工具,能够帮我们向用户传达游戏的乐趣体验。不幸的是,作为游戏设计师我们经常因为对于机制的错误理解而陷入某些误区。而这些错误的推断导致我们开始以一种错误的方法设计游戏。这种错误的推断指的是什么?下面我将列举一个相关情节,并阐述这个观点与我们的主题有何关系。

想象你正从事一份较低水平的工作,并且被各种规则和约束压得紧紧的。你跟老板的儿子共事,而你会发现他很少遵循这些规则和限制,但是在你刚接触这份工作时,你的上司便开始反复强调其重要性。你还会发现,你的上司不会因为老板儿子不遵守这些规则而批评他。而你便能够因此推断“如果老板的儿子能够这么做,那我应该也能这么做,上司也不应该再严格要求我遵循这些规则了。”然后你便开始放纵自己不再遵循这些规则,而这时你的上司便会跟你说:“嘿,难道你想被辞职吗?最好老实点!”然后你便震惊地询问上司为什么要责骂你。他便回答到:“因为你违反了规则。”然后你回应道“但是老板的儿子也这么做了。”这时候你的上司会非常严肃地向你解释:“那是因为,他是老板的儿子。”

我之所以列举这个故事是想以此说明,我们作为游戏设计师在看待已发行游戏时也常常犯上述故事主人公一样的错误(即故事中主人公不能理解不同身份的人适用于不同规则)。除非你的游戏打上Knzia,Kramer或者Seyfarth等活字招牌,要不你便很难吸引潜在发行商主动选择你的游戏。如果你的游戏并没有任何知名度,你就必须为他们创造出选择你的游戏的“理由”,也就是说你必须努力创造出一个真正有趣的游戏主题。

讽刺的是,欧洲游戏设计师关于主题的想法总是后知后觉。在他们眼中,如果一款游戏必须拥有主题,那么它就只是一项必须完成的任务但却不属于需要优先考虑的内容。根据这种事后才添加主题的游戏,我们发现许多游戏设计师都是基于其它游戏的版式去设计自己的游戏,并且那些游戏虽然拥有强大的发行商,但是不得不说,它们的主题却真的很糟糕。

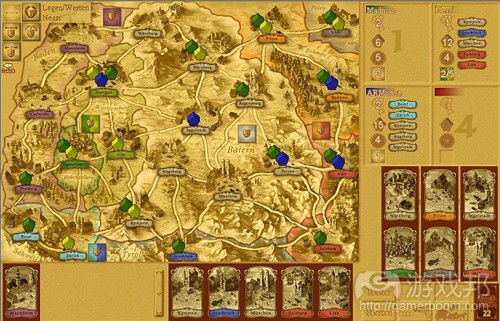

以2006年的“德国年度桌游大奖”(Spiel des Jahres)优胜者《Thurn and Taxis》为例,它是由著名设计师,即曾经创造了大受好评的《Puerto Rico》的Andreas Seyfarth设计的一款游戏。《Thurn and Taxis》的主题是什么?

建筑,邮政,路线……

现在,我希望你将自己想象为一名并非发行商首要选择的对象,尝试着向他介绍自己:“你好。你可能不认识我,但是我设计了一款游戏,并且希望你能够看看这款游戏。这是一款关于……送信的游戏”

这听起来会有趣吗?

如果你只能够描述游戏主题而非游戏机制,那么这样的游戏还会有趣吗?听者还会愿意玩这款游戏吗?或者,一个新玩家会只是基于主题而尝试这款游戏?不然,你就只能祈祷发行商会欣赏你的游戏了。

很多游戏设计师在设计欧式游戏时总是更加侧重于游戏机制而忽略了游戏主题。他们认为机制能够更好地推销游戏,而相比之下主题就没这么重要了,然后他们列举了一些主题很无趣的游戏,以及一些主题与机制没有联系的游戏作为论据。但是我认为,如果你并非老板的儿子,你就必须照章办事。如果你不是Andreas Seyfarth,你就别想打着这块“活招牌”去销售游戏。

如果一款游戏并没有高知名度的设计师,那么主题便是游戏吸引玩家的最佳卖点。我们必须投入更多时间去创造一个有趣的主题,并且以此吸引更多玩家的注意。不幸的是,我们中的许多人常常忽视了这一点,即并未投入足够的时间和精力去创造游戏主题。同时,即使某些设计师看到了主题的重要性,他们却不知道如何创造出一个有趣的主题。举个例子来说,如果你的游戏拥有一个很一般的“商业”主题,那么你是否能够立刻知晓游戏陷入平庸之列的原因?一个好的主题必须能够激发潜在玩家的想象力。而“商业”主题却很难具有这种功能。

主题必须能够激发玩家发挥想象力,但是游戏主题却不一定需要是一些大爆炸,异太空,行星大战或者银河冲突等大场面大内容,一些简单的小故事,如蚂蚁搬家,也是可以的,关键是它能够让玩家发挥想象力并愿意尝试你的游戏。

我认为,除非我们的目的是设计一款纯粹的抽象游戏,要不我们就应该尽早地选择游戏主题,然后以主题为指明灯,决定游戏应该采取或者避免哪些机制。

此外,如果有人说:“嘿,这听起来是款有趣的游戏,我尝试看看。”然后便坐下来玩游戏,但是如果他发现游戏机制与游戏主题缺少联系,他便会对此感到失望而萌生厌倦感。如果你的主题是可“扩展的”,这就意味着“有些机制能够表现出蚂蚁聚集食物的样子,但是表现方法却非常抽象”,这时你的游戏便更加难以调动玩家的想象力了。

要让人们真心喜欢上一个游戏主题,必须让他们感受到自己在游戏中的“角色”,所以游戏必须尽量保证这些角色具有存在意义。如果一个人问自己“我要是在那个位置上我会怎么做且为什么要这么做?如果我的目标是以某种方法筑墙,而为什么游戏故事中的虚拟人物能够颁发奖励积分?”你的主题必须具有移情作用,能够引起玩家的联想。如果游戏中有个“国王”角色能够奖励“积分”,玩家便能够轻易地知晓原因,而如果玩家是游戏中的“国王”,那么国王便要根据判断系统的标准奖励积分,但如果玩家处于这种情境,他们还是会觉得这种做法合理吗?也许这听起来很愚蠢,但是却未脱离逻辑,所以很多欧洲游戏设计师都以此方法确立游戏主题。

在你的游戏中是否存在着机制与故事脱节的情况?如果你的主题能够调动潜在发行商发挥想象力,他们便会愿意听你宣传游戏。但是后来,如果他们发现你的主题和机制没有多大关联性,并且他们难以再去想象你的游戏“故事”了,那么他们也不会愿意去尝试你的游戏。

如果一款游戏拥有有趣的故事,下一步它就必须想办法获得关注(如果没有任何发行商愿意正视这款游戏,那么它又有何设计意义)。实际上,很多游戏设计都缺少足够的创造性,难以打破现存游戏环境的束缚。换句话说,如果一位设计师要设计一款带有科幻主题的角色扮演游戏,他就不能闭门造车,两耳不闻窗外事。现在的市场上已经有《龙与地下城》这般优秀的游戏了,以致其它科幻类角色扮演游戏总是难以脱颖而出获得更多关注,因为任何科幻类角色扮演游戏总是会被人拿来与《龙与地下城》进行比较。除非新游戏具有某些不一样的新内容,要不它们便很难在这种较量中获胜。

关于主题和欧洲游戏设计最后一点需要考虑的是,欧洲游戏更倾向于“简单的”规则。通常,为了从一个主题中引出更多内容,我们必须设立更多规则。而我的另外一个领悟是,也许这并不是一个必要情况。如游戏机制“嘿,那是我的鱼!”是否具有主题性?当然。而且这也是个非常简单的主题。关键是,这个主题并不能让玩家产生将游戏机制与故事联系在一起的逻辑感。游戏中不需要设定无数具有主题性的规则,只要它的故事能够让玩家感受到价值所在,并愿意花时间体验游戏即可。

游戏邦注:原文发表于2008年4月28日,所涉事件和数据均以当时为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Importance of Theme in European Game Design

Mike Compton

I have recently had some major epiphanies as a game designer – specifically with respect to the importance of theme. In fact, one might say that these epiphanies of mine represent critical conceptual breakthroughs in my personal journey towards becoming a better game designer (I’m afraid that many more will occur over the years as I continue to learn how much I don’t know). To communicate my new found understandings to the fullest extent possible, let me first back up and paint a big picture by beginning with two basic premises:

1. There are many people out there designing games.

I attend a monthly meeting with a group of local people who get together and playtest each other’s game prototypes as well as discuss various issues in the realm of game design. On a larger scale, on the Board Game Designers Forum website and on the game design forum on Board Game Geek, there are many many people having conversations about game design. There are also many more people out there unfamiliar with these venues who are also trying to design games on their own (either with a serious intent on making quality games or simply out of curiosity). My point here is that there are LOTS of people out there trying to design games.

2. Very few people out there are designing really “good” games.

With this second premise, I automatically introduce the question of “What really represents ‘good’?” In my game evaluation criteria I mentioned six specific areas of evaluation that an evaluator can rank on a scale of 1 to 7. These six areas are:

-Clarity

-Flow

-Balance

-Length

-Integration

-Fun

Many game designs are simply in the early stages of their development and, thus, have not “matured” yet into good games. They are still in the “the – game – stinks – but – has – the – potential – to – be – good – after – lots – of – refining” stage (for more actual specifics – sans humor – on my scale of the various stages of game design click here). However, even with refining, many game designs still don’t truly progress into the “6″ or “7″ ranges with respect to the categories outlined previously. They simply remain average or mediocre games. True, the first challenge is to get a game out of the lower ranges (i.e. to try and get the game to a point where it’s not fundamentally broken or completely a chore to play) but many game designers don’t progress their designs to a truly great level (myself included). Why is this?

A quote from Adam Smith applies here. Before writing “Wealth of Nations”, Mr. Smith wrote a book entitled “The Theory of Moral Sentiments”. In that book, he makes the following statement that is applicable to our current discussion:

“In all the liberal and ingenious arts, in painting, in poetry, in music, in eloquence, in philosophy, the great artist feels always the real imperfection of his own best works, and is more sensible than any man how much they fall short of that ideal perfection of which he has formed some conception, which he imitates as well he can, but which he despairs of ever equalling. It is the inferior artist only, who is ever perfectly satisfied with his own performances. He has little conception of this ideal perfection, about which he has little employed his thoughts; and it is chiefly to the works of other artists, of, perhaps, a still lower order, that he deigns to compare his own works.”

It takes a lot of work to make something truly great. And, lots of work equals lots of time. Also, to get something to a truly great level, one must be willing to listen to harsh criticism – not with the intent to be defensive – but with the intent to learn. We also must be able to have a correct set of standards in our minds so as to be able to properly apply our own set of criticisms to our game designs – lest they languish in the realm of mediocrity.

My recent epiphanies concern the development of theme in European game design and how many of us are “lazy” in our theme development. We allow ourselves to be satisfied with sub-par themes. This relates to the “Integration” category in my game design criteria but it deals with issues greater than just integration within the game’s inter-relating parts. First, let’s explore why theme is so important and then we’ll look at why many of us justify our own “theme laziness”.

From the standpoint of potential publishers, manufacturers, and game players, they need a reason to play your game. They need a solid answer from within themselves to the question “Why should I take a look at this person’s game?” For many game designers, their internal rationale concerning the answer to that question goes something like this:

“I designed this game – isn’t that reason enough? I’ve nurtured this little game design since it was just a baby and I know in my heart just how awesome it is.”

Unfortunately, other than in the case of automatic “yes men” such as immediate family and friends (who will usually just offer you encouragement on your game design instead of actual useful, critical feedback) others out there who are making decisions with respect to which games to look at and which ones not to (as well as which games to invest in financially and which ones not to) will not find such rationale as providing a sufficient enough reason to spend their time listening to you pitch your game – much less sitting down to play your game.

Game designers must master the critical art of empathy – the ability to look at their game design from a removed perspective and not merely from the “eye glasses” of their own experiences and biases. So, what kind of “reasons” for trying a game or are worth appealing to in other people?

In a previous article I wrote on the theory of what makes for “fun” in a gaming experience, I detailed some of the many specific reasons why someone may derive enjoyment out of a game. I listed 17 different motivations or purposes that people apply in their rationale for why they are participating in a game or what they are trying to get out of a game. Also, in another previous article, I detailed a variety of mechanics that can be used in the process of designing a game.

It must be kept in mind that game mechanics are a means to an end. They are used as vehicles to help convey a fun experience to an audience. Unfortunately, we as game designers are often misguided in our perception of mechanics because many of us have inferred the wrong things from games we have seen that have been published out there in the realm of European games. These incorrect inferences we make can cause us to begin the process of designing games with the completely wrong approach. What type of inferences am I talking about? Well, let me present a quick scenario and then I’ll discuss how it relates to our topic.

Imagine working at a lower level job where there are a lot of rules and restrictions in place. In that setting, you find that occasionally you work alongside the owner’s son. You notice that the owner’s son doesn’t always follow these small rules and restrictions that your manager strongly emphasized to you when you began the job. You also notice that the manager doesn’t criticize the owner’s son for breaking these smaller rules. In your mind you make the inference “if it’s okay for him to do it then it’s okay for me to do it and the manager must not have been too serious about those rules in the first place”. Then, you start letting yourself lapse in your adherence to these rules and, almost immediately, your manager says “Hey, do you want to get fired? You had better shape up!” Shocked, you wait until your shift is over and you approach your manager. In a very honest and genuinely curious fashion you ask your manager why he reproved you. He responds “because you were breaking the rules”. You then reply “but so was the boss’s son”. Your manager then drops his head, rubs his eyes, puts his hand on your shoulder, looks you in the eye and, almost as if explaining a concept to a very young child, explains “but he’s the boss’s son”.

The point of this story is that we as game designers look at many of the games that have been published out there and infer the wrong kinds of things from them (much like how the main character in my story didn’t understand that different rules apply based on who you are in a given scenario). Unless your name is Knizia, Kramer, or Seyfarth, mechanical game descriptions alone will not be enough in most cases to sufficiently inspire potential publishers to look at your game. Without the benefit of name recognition, you have to reach out to their imagination and give them a “reason” for looking at your game and that can most easily be achieved by developing an interesting theme.

The ironic thing is that theme is often an afterthought in the minds of those who are trying to design European games. It’s looked at as a required necessity – but not a priority – and, if the game must have a theme, it’s slapped on. This type of theme-being-an-afterhtought type of thinking is justified by inferences designers make based on other games that have been published by major publishers that employ themes which are, quite honestly, pretty lousy.

Here’s an example of what I mean. Take the 2006 Spiel des Jahres winner: “Thurn and Taxis”. It was designed by Andreas Seyfarth – the famous designer of the top rated game “Puerto Rico”. What’s the theme of Thurn and Taxis?

…..building…..postal……routes…..

Now, I want you to imagine yourself – someone who is not on a first name basis with a publisher – trying to pitch your game to a publisher by saying, “Hi. You don’t know me but I’ve designed a game I was hoping you would look at. It’s about…… delivering the mail……”

Doesn’t sound very interesting does it?

If you were to only be allowed to describe your game’s theme and you weren’t permitted at all to describe the mechanics, would your game sound interesting to play? Would you want to play it? Honestly? Further, would a complete stranger want to play your game based on the theme alone? If not, then good luck trying to get a publisher to look at your game.

Many game designers who are trying to design European style games are studious with respect to their mechanics but lazy with their themes. They think their mechanics are what will sell their game, that the theme isn’t that important, and then they justify their rationale by citing plenty of examples from the field of published games where the themes are uninteresting or where there is no connection at all between the theme and the mechanics of the game. I’m here to tell you that, from my perspective, if you’re not the boss’s son, you have to play by the rules. And, if you’re not Andreas Seyfarth, you’re probably not going to sell your game based on it being about delivering the mail.

This my friends is the water in which we swim. The theme of one’s game is really its best selling point unless one is a well recognized designer. We must invest more time in developing a theme that is interesting and that naturally invites others to want to play our game. Unfortunately, most of us don’t invest enough time or creative energy in this process. I would also contend that, even if most designers consider theme to be important, they don’t have the acumen to truly see what makes for an interesting theme and what doesn’t. For example, does your game have a generic “business” theme? If so, can you see why that immediately saddles your game with baggage? A theme needs to reach out and capture the imagination of your potential audience. Does “business” really do that? In very few cases it does but not for many people.

A theme needs to engage the imaginations of the players – but don’t take my thesis too far in the other direction either. A game’s theme doesn’t have to be an in-your-face epic of explosions, space aliens, massive planetary wars or galactic conflicts to be effective. It may simply be an amusing little story about ants in a colony – but it must appeal positively to a person’s imagination in some way such that they will want to play your game.

I would also contend that, unless our intention is to design a purely abstract game, we must select a theme as early on in the process of designing a game as possible so that the theme can serve as a guiding light to help us determine which mechanics should be in the game and which ones should not.

Further, if someone says, “Hey, that sounds like an interesting game. I’ll try it.” and then sits down and is introduced to a series of mechanics that really don’t reflect the theme at all, you’re going to disappoint and perhaps even annoy the people who decided to give you the benefit of the doubt. If your theme is a “stretch” – meaning something like “yeah that bidding mechanic ‘could’ represent ants gathering food – but it’s really abstract” then your game’s ability to inspire people’s imagination will immediately lose its momentum.

For many people to really appreciate a theme, they need to feel a sense of what their “role” is in the game and it needs to “make sense” to them. If a person is asking themselves “Why would I do this if I were in that position? If my goal is to build walls in a certain way, why is the fictional person in the ‘story” of the game awarding points in the manner that they are?” There needs to be a sense of empathy that can easily be evoked from the players. If there is a “king” that awards “points”, can the players easily see how, if they were the “king” in the game, that the way the king is awarding points is by using a system of judgment that, if the players were in the same situation, would seem reasonable to them as well? Just pulling an example out of thin air, does it make sense to the players that the king is awarding points because of how many different horses a player has ridden in a given week? I know that may seem silly but it’s not too far removed from the logic many designers of European games settle for when determining their theme.

So, is there a lack of connection between the mechanics and the story your game is trying to tell? If your theme appeals to a potential publisher’s imagination in a positive way, they may listen to you pitch your game. But then, afterwards, if they don’t feel a connection between the theme and the mechanics as you pitch your game, if they can’t visualize the “story” of the game, they will probably not try your game. (For a good discussion on theme summarizing a game, check out Jonathan Degann’s article over at the Journal of Board Game Design.)

Even if a game is a “good” game with an interesting story, getting noticed is yet another step (if a game is designed in the forest and no publisher is around to see it, did it really get designed)? The fact of the matter is, many game designs out there are simply not original enough to break out of the baggage that naturally results from our pre-existing gaming environment. In other words, someone designing, say, a role-playing game with a fantasy theme is not designing their game within a cultural vacuum. This world we live in is a world where Dungeons & Dragons already exists. Were it not so, a fantasy based role-playing game would maybe have more traction in getting noticed. As it is, natural comparisons will be made between any fantasy based RPG and D&D. Unless the new game offers something that has here-to-for not been seen, it’s unlikely that the game will “win” the natural comparison that will be made by many out there in the audience of potential game buyers as well as potential game publishers and manufacturers between the game design in question and an already existing industry standard. (The irony in this process is that it’s likely the ideas for many of the games being designed by aspiring designers were conceived of and nurtured within a realm of experience with the industry standard games the resulting game designs will be ultimately compared with.)

One final thing to consider with respect to theme and European game design is how Eurogames tend towards a certain standard of “simplicity” in the rules. Usually, to evoke a theme more and more, there is an assumption that there needs to be more and more rules to help flush out that theme. Another one of my epiphanies is that this is not necessarily the case. Are the mechanics in the game “Hey, That’s My Fish!” thematic? Yes they are. Are they simple? Yes they are. The point is that the mechanics in “Hey, That’s My Fish!” don’t ask the player to make a huge leap in logic so as to accept a real stretch in associating the mechanics with the game’s story. A game doesn’t have to have tons of rules to be thematic. It just needs to be “true” to its story and its story needs to be something others will consider worth taking the time to experience. (source:mike-compton)

上一篇:举例分析游戏制作、测试和发布过程

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号