分析“史诗”游戏的三个普遍特征及条件

作者:Lewis Pulsipher

我感兴趣的是多数玩家称为“史诗”的游戏设计,而不是被视为史诗的某种游戏经历。我玩过《First Edition AD&D》的史诗冒险,但我并没有将《龙与地下城》称为史诗游戏。

我在谷歌中搜索“史诗”的定义,结果如下:极度令人印象深刻,超越普通情况(尤其在大小或范围上)。

字典上的定义是:英雄般的,雄伟的,给人产生极深刻印象。

这些定义的共同点在于都是事物给人产生的感觉,而并非事物的逻辑。游戏“感觉起来”很史诗,也就是游戏卷入了玩家的情感。但是,《龙与地下城》在同样卷入了玩家的情感,却不能称为史诗游戏,虽然游戏中含有史诗冒险。因而,仅仅带有情感投入是不够的。

我将“史诗游戏”的特征分为3个类别:范围;玩家沉浸;紧张感和记忆价值。接下来,我将简单描述下这些特征,然后用具体例子来阐述更多细节。但史诗游戏并不一定拥有以下所有的特征,这是任何复杂定义都会带有的瑕疵。

1、范围

地理上和时空上的广阔场景,同时不令人感到抽象

呈现对大量人物至关重要的宏伟战争

不平淡的主题

故事架构发生巨大改变

2、玩家沉浸感

游戏玩法富有深度,包括有较高的再玩性

游戏长度或复杂性卓著(抑或两者兼有)

3、紧张感和记忆价值

游戏玩法随时间发生巨大改变,游戏最后结局的玩法感觉与游戏开始之初的玩法大不相同

胜利者并不确定

不对称

游戏产生你永远铭记的“故事”,而且此后说起这段故事时感到快乐

讨论:

1、范围

地理上和时空上的广阔场景,同时不令人感到抽象

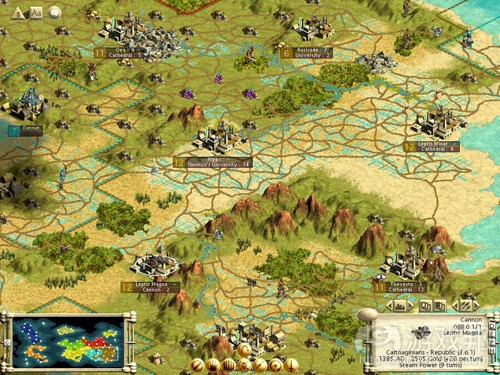

涉及到许多个世纪或国家乃至整个世界的事情(游戏邦注:比如大不列颠王国、意大利、世界史或7世纪的事件),这样的游戏往往会被认为是史诗游戏。比如,《文明》、最早的桌游和之后的电脑游戏都可以算是史诗游戏。但是,并非所有大范围游戏都可称为史诗游戏,比如《Vinci》和《Risk》。我想是因为它们给玩家的感觉过于抽象,已经不再有“现实世界”的感觉。与《文明》主题相同的短游戏也不能算史诗游戏,比如我曾经设计过90分钟版本的不列颠王国历史游戏(游戏邦注:游戏中删除了受罗马征服的部分),这款游戏不太可能给多数玩家带来史诗般的感觉。

呈现对大量人物至关重要的宏伟战争

某些有关拿破仑的游戏符合这个条件,还有部分有关美国内战的游戏。《魔戒圣战》和《帝国曙光》符合这个标准,虽然它们所讲述的并非“真实的”战争。战争可以是虚构的,只要玩家不怀疑,能够接纳这个虚构出来的战争。

不平淡的主题

你不可能将销售房地产的游戏(游戏邦注:比如《大富翁》)视为史诗游戏。建造房屋或吃鱼的游戏同属此类。众人期望的史诗游戏应当有“史诗般的故事元素”,比如成为国王或者拯救世界。

故事架构发生巨大改变

我不认为宏伟的故事是史诗游戏的必要条件,而且许多有着宏伟故事的游戏也确实称不上史诗游戏。但是在某些史诗游戏中,游戏“故事”却会发生重大改变,形成含有开端、高潮和结局的长篇故事,这使得游戏结局的情境同游戏开始的情境大为不同,几乎就像是换了个世界。以《Britannia》为例,游戏早期多数玩家的目标是对抗罗马的征服。而到游戏后期,玩家的战斗目标是成为英格兰的国王,这与前期的故事完全不同。

2、玩家沉浸感

游戏玩法富有深度,包括有较高的再玩性

对于游戏玩法的深度,显然每个人都有不同的想法和观点。这个方面也是我认为《Vinci》和《Risk》算不上史诗游戏的原因,因为它们的游戏玩法深度并不高。但是,你也可以认为《History of the World》同样如此,每个人都可以有自己的观点。

游戏长度或复杂性卓著(抑或两者兼有)

《文明》是受玩家广泛认可的史诗游戏。如果游戏总时长只有两个小时,那么还能够传达出史诗感吗?许多人都觉得这根本做不到。那么,能否在不失史诗感的前提下简化玩家的动作呢?或许这有可能实现。这样看来,游戏的一个神秘组成部分似乎是游戏长度而不是复杂性。

史诗游戏无需既长又复杂。以《Britannia》类游戏为例,不列颠的历史很长但并不复杂。意大利的历史要复杂得多,尽管时间并不长。

但是,史诗游戏至少需要满足1个条件,要么很长,要么很复杂。

这样看来,角色扮演类游戏几乎都算不上史诗游戏。

在角色扮演类游戏中,你扮演了游戏中某个具体角色。比如,你会是团队领导者,或者是城堡建设者。这很像你在现实世界中的生活。但是在许多史诗游戏中,你无法识别出自己扮演的是哪种具体的角色,最多只能意识到自己扮演的是某一类的角色(游戏邦注:比如国王、总统或将军等)。或许,游戏感觉起来更具史诗性正是因为你无法识别出自己扮演的具体角色。

在许多史诗游戏中,你甚至需要操纵多个国家。

3、紧张感和记忆价值

在以下同紧张感和记忆价值相关的特征列表中,我们需记住一个流行电子游戏共同的特征,那就是“拟真性”。拥有拟真性的游戏并不一定是史诗游戏。

游戏玩法随时间发生巨大改变,游戏最后结局的玩法感觉与游戏开始之初的玩法大不相同

这句话的意思是,随着时间推移你逐渐接近游戏的结局,而此时的游戏似乎与前期有很大的不同。比如在《Britannia》中,刚开始多数玩家努力抗争罗马帝国的征服,保持国家的完整,甚至给罗马带来点麻烦。在游戏末期,所有玩家都专注于争夺英格兰的王位,努力杀死自己的竞争对手。前后期的目标需要完全不同的战略。在《History of the World》中,玩家刚开始只控制面积相对较小的区域,但是到最后动作的范围扩张到整个世界。

而且,游戏前期的重要动作或许在游戏后期的效能会减弱,因为玩家所掌控的范围逐渐变大。

胜利者并不确定

对于多人游戏来说,如果你可以在某个时刻确定谁会获得最终的胜利,那么就证明这款游戏的设计并不完善。这会激怒玩家,减弱紧张感,最终沦陷成为《Risk》和《Vinci》那样的游戏。

在双人游戏中,如果某个玩家显然会获得最终的胜利,那么另一个玩家很可能就会放弃或直接投降,这便毫无史诗性可言。象棋中的长期持久性争斗可以被称为“史诗战”,但其游戏本身却并不具备史诗感。

在这个方面,设置得分的游戏可能会面临问题。、Hasbro版《History of the World》设置得分加成,由此来对处于领先的玩家构成影响。在《Britannia》中,国家和颜色在不同时间有着不同的得分率,所以即便是专家级的玩家也无法知晓如何保持领先地位。

不对称

在非对称游戏中,每个玩家有着不同的起始位置和环境。与之相反的是对称游戏,“欧洲”风格游戏的普遍特征是,每个玩家的起点完全相同。抽象游戏更趋向于对称化,因而不容易产生史诗感。象棋算是史诗游戏吗?我不这么认为。

多数史诗游戏是历史或虚拟历史游戏,而历史本就不具有对称性。所以我们可以将不对称性视为史诗游戏的特征。

游戏产生你永远铭记的“故事”,而且此后说起这段故事时感到快乐

有些游戏含有令人记忆深刻的内容,有些游戏没有。前者已经不只是游戏了,玩家从中收获了“经验”。这样说来,又回到了游戏“沉浸”的想法上了。多数“欧洲”游戏不符合这个条件。

“伟大”的游戏具有这个特征,这是毫无疑问的,但有时它也是“史诗”游戏的特征。

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2011年7月17日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

What makes a game “Epic”?

Lewis Pulsipher

While I don’t believe a game designer can deliberately set out to design a “great” game, I DO believe a designer can set out to create an “epic” game, though this effort is just as subject to failure as any other game design.

I’m interested here in game designs that most players would call “epic”, not in an individual play of a game that might be regarded as epic. I’ve played and refereed epic adventures of First Edition AD&D, but I wouldn’t call D&D an epic game.

“Define:epic” at Google gives this first definition: “very imposing or impressive; surpassing the ordinary (especially in size or scale); ‘an epic voyage’; ‘of heroic proportions’; ‘heroic sculpture.’”

Another dictionary meaning: “heroic; majestic; impressively great”.

In common among these definitions is feeling, rather than logic. Games “feel” epic–they emotionally involve the player. But once again, D&D emotionally involves the player yet is not an epic game, though there can be epic adventures. There’s more than just emotional involvement.

Any and all definitions of anything, of any length, can be picked apart. As I am interested in characteristics that define an “epic game”, my list must be fairly detailed, hence open to even more nit-picking. Nonetheless, I’m going to take a stab at it. In the course of the discussion we’ll see some of the things designers can try to do to create an epic game.

I’ve settled on a number of characteristics that can be divided into three categories: 1) scope, 2) player commitment, 3) tension and memorability. I’ll briefly describe the characteristics, then talk about them in more detail with some examples. Epic games won’t necessarily have every characteristic. That’s the flaw of any detailed definition.

1) Scope

• Geographically and chronologically broad setting without feeling abstract

• Represents a titanic struggle important to very large numbers of people and many generations

• Non-mundane theme

• Story “arc” reflecting great changes

2) Player commitment

• Depth of gameplay including high replayability

• Sheer length or complexity (or both)

3) Tension and memorability

• The gameplay reflects major changes over time, end-of-game gameplay feels very different from the beginning

• Uncertainty about who’s winning

• Asymmetry

• The game engenders “gaming stories” that you remember fondly and retell with pleasure (or chagrin!)

Discussion:

1) Scope

Geographically and chronologically broad setting without feeling abstract

“Sweep of history” games that involve many centuries and countries or the world, such as Britannia, Italia, History of the World, and 7 Ages, are generally regarded as epic. So, too, is Civilization, both the original boardgame that preceded the computer games and the computer games. Yet other games with big scopes are not epic, for example Vinci and Risk, I think because they feel so abstract that the “real world” no longer feels present. A short game with the same subject might not feel epic: for example, I’ve designed a 90 minute version of Britannia (admittedly leaving out the Roman conquest) that is unlikely to feel epic to most players.

Represents a titanic struggle important to very large numbers of people and many generations

Some Napoleonic games might qualify here, perhaps even some American Civil War games. War of the Ring and Twilight Imperium qualify, even though the struggle is not “real”; it can be fictional, as long as players suspend their disbelief and adopt the fiction. In all cases these are great “slugfests”.

Non-mundane theme

You’re not likely to regard a game about selling real estate as epic (Monopoly!). Nor a game about building a house. Nor a game about eating fish. Many people expect “epic story elements” from an epic game, such as becoming king or saving the world.

Story “arc” reflecting great changes

I don’t think a great story is necessary to an epic game, and certainly many games with great stories are not epic. Yet in some epic games, the game “story”, what it represents, reflects major changes over time, a saga with beginning, middle, and end, so that the situation at the end of the game is very different from the beginning, almost like it’s a different world. To use Britannia as an example, early in the game most players vainly try to fight off, or accommodate, the Roman conquest. Late in the game players are fighting to determine who will be king of England, a very different story.

2) Player commitment

Depth of gameplay including high replayability

This is clearly open to differing opinions about depth of gameplay. This is another case where Vinci and Risk fail my definition, as there is little depth to their gameplay. But you could argue the same thing about History of the World.

Sheer length or complexity (or both)

Civilization is one of the most widely acknowledged epic games. Can you have a two hour Civ game and not lose the epic feel? Many would say “no”. Can you drastically simplify what the players do without losing the epic feel? Hard to say. It seems that length, rather than complexity, is part of the mystique of the game.

An epic game need not be both very long and very complex. I’d cite Britannia-like games here, as Britannia is lengthy but not complex. Italia is considerably more complex, though derived from Britannia.

But an epic game will very likely be at least one or the other, very long or very complex.

Oddly enough, often this means no role assumption is involved!

In role-assumption games, you can conceive yourself as taking on the specific role of an individual person. For example, you might be a squad leader, or a castle builder. It’s too much like something you might do in the real world. Yet in many epic games you cannot name a specific individual that you play, at best you might take on the roles of a series of individuals (kings, presidents, generals). Perhaps a game (as opposed to a D&D adventure) feels more epic for the very reason that you cannot identify with one (mortal) person.

In many epic games you don’t even play just one nation, but several. You have an “omnipresent” (though not omnipotent or omniscient) point of view.

3) Tension and memorability

In the following list of characteristics related to tension and memorability, we might keep in mind a trait of many popular video games, “immersiveness”. Yet a game can be immersive without being epic… Immersion: “state of being deeply engaged or involved; absorption.”

The gameplay reflects major changes over time, end of game gameplay feels very different from the beginning.

Another way to put this, is by the time you get to the end of the game, it seems very different from the game you were playing in the beginning. “Sweep” games tend to feel this way. In Britannia, for example, in the beginning most players are trying to survive the Roman conquest with a healthy nation, yet give the Roman some trouble. At the end, all are concentrating on who will be king of England, and often trying to kill opposing candidates. These require quite different kinds of strategies. In History of the World, players begin in a relatively small area, but by the end are acting all over the world.

Further, what was an important and useful move early in the game might be a weak, poor move by the end. That is, there may be an increase in “power” and scope of the things the player can do.

Uncertainty about who’s winning

If you certainly know who’s winning at a particular time, a multiplayer game becomes subject to all kinds of defects such as kingmaking and sandbagging. This tends to annoy players and reduce tension, and may be another downfall of Risk and Vinci.

If it’s a two-player game and one player is obviously winning, the other will probably resign/surrender–end of game, no epic provided. A long, drawn-out struggle in chess might be called “epic”, but the game itself is not.

Point games can be a problem. The plastic Hasbro version of History of the World added secret scoring bonuses in an attempt to obscure who is in the lead. In Britannia the nations and colors score at different rates, at different times, so it’s never quite clear even to experts who is in the lead, by how much, until the game ends.

Asymmetry

In asymmetric games, each player has a different starting position/situation. The opposite is symmetric, a common characteristic of “Euro” style games, where each player starts with an identical position. Abstract games tend to be symmetric, and tend not to feel epic. Is chess an epic game? I don’t think so.

Most epic games are historical or pseudo-historical, and history is rarely symmetric. So we may only be seeing a symptom, not a cause, in this characteristic.

The game engenders “gaming stories” that you remember fondly and retell with pleasure (or chagrin!)

Some games result in memorable sessions, some do not. They are more than games, they are “experiences”. This goes back to the idea of “immersion”, of buying into the game. It leaves out most “Euro” games, which tend to be somehow inconsequential–games, not experiences.

This is certainly a characteristic of “great” games, and is sometimes a characteristic of “epic” games. (Source: Pulsipher Game Design)

上一篇:简述游戏玩家与游戏体验者的区别

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号