以叙事理论解析电子游戏UI设计要点

作者:Dave Russell

用户界面(UI)是游戏开发中面临的最大挑战之一。开发者总希望尽可能多地透过小小的屏幕将所有信息传达给玩家。如果一款游戏的用户界面过于糟糕,那么即使再优秀的游戏理念最终也只能创造出不尽人意的用户体验。

设计师可以应用多种理论去分析用户界面,并做出各种选择。而我们将在这里讨论其中的一种理论,即叙事理论。这一理论主要是来源于文学,电影和戏剧中的叙事理论。叙事主要是指设置一个故事的世界,因此它侧重于将游戏当成故事体进行分析。

关于这一理论有2大核心要点:叙述和“第四道墙”。

叙述

叙述是一种信息,即向我们传达一个行为的细节,所发生的事件或者事件经过等。简单地来说,它是指设计师希望传达的故事内容;就像《俄罗斯方块》里砖块从空中落下并安置在合适的位置上或者《机械迷城》中通过一片陌生领域的旅程。

并不是所有游戏元素都与叙述内容有关。例如游戏菜单和HUD,因为游戏角色并未与这些元素直接联系在一起。但是这也不等于这些内容与叙述一点关系都没有,例如一款科幻游戏的GUI中必然会呈现科幻元素。

第四道墙

第四道墙实际上是一堵并不存在的“墙”,并且以此来维系玩家与游戏世界之间的联系。而为了让玩家真正沉浸到游戏中去,游戏就必须让玩家能穿过这第四道墙。而为了让玩家能够更轻松地穿梭于现实世界与游戏世界之间,用户界面设计者就必须尽可能地传递给玩家更多信息。

玩家将最新的游戏成就发布到Facebook其实也就是游戏对于第四道墙的延伸。

用户界面组件

现在我们可以自问两个关于用户界面组件的问题:

组件是游戏故事的组成内容吗?(是叙述的组成内容吗?)

组件是游戏空间的组成内容吗?(是第四堵墙中隐藏的内容吗?)

而基于这两个问题的答案,我们可以将UI组件分为四大类型:叙述世界,非叙述世界,空间以及中间内容。

从以下的图表中我们能够清晰地看到两个问题与这些分类内容之间的关系。

叙述世界组件

根据叙述世界组件回答上述两个问题:

用户界面组件存在与游戏故事中吗?是的

组件存在于游戏空间吗?是的

叙述世界组件能够提供给玩家一些提示信息而不会让他们从游戏世界的叙述中分散注意力。这些信息是玩家所控制的角色以及游戏世界中的其它角色所知道的内容,并且能够用于彼此间的相互作用。如此设置让游戏体验更加具有沉浸性与戏剧化。

《孤岛惊魂2》便尝试着创造出这种叙述世界体验,并且游戏设置中不包含HUD。它通过使用各种游戏内部小配件和道具而让玩家无需参考外界元素便能够获得所需信息,或者让游戏世界更具有现实性。

虽然这种组件能够让游戏更加具有沉浸式体验,但是如果设置不合理的话,也会带来负面效果。例如在冒险游戏《冥界狂想曲》中,玩家每次游戏都必须在库存中寻找某个道具。这种设置只会让玩家感到沮丧并不再信任游戏,而最终退出游戏。

不同的游戏类型会选择不同的沉浸式体验与现实成份,如果忽略了这一点,你的故事叙述也会受到影响。

在《冥界狂想曲》中,游戏角色的头转向其他对象就预示着他们正在进行交流。尽管这是一种具有现实性的传递信息途径,但是整体的运转看来却太过笨拙且不自然。如此会让玩家在游戏中分心,并且不如传统冒险游戏中所使用的发光物体以及光标变化等设置有用。

叙述世界UI例子

设计能够取代一般HUD元素的叙述世界UI组件需要采取一个有效的方法。以下我将列出一些例子:

在即时策略游戏中,叙述世界组件是指某些元素,如单位和建筑遭到破坏时所呈现出的视觉效果。

在《孤岛惊魂2》中,玩家可以在指南针的协助下航行于游戏世界中——这种设置比起其它在HUD中使用非叙述世界指南针的游戏更具有吸引力。

《死亡空间》并不采用典型的生命值表现方式,而是在角色的衣服上设置高科技仪表以预示玩家的生命状况。

非叙述世界组件

根据非叙述组件回答上述两个问题:

用户界面组件存在与游戏故事中吗?不是

组件存在于游戏空间吗?不是

我们总是很习惯地在游戏中使用HUD,这一系统能够以一种相对简单的方式提供给我们一些重要信息。如果设置合理的话,玩家甚至察觉不到它的存在。

有些游戏,如《战争机器》采取了极其简单抽象的方法限制了HUD内容的数量,也有些游戏,如《魔兽世界》则提供了大量的HUD信息。

一个滥用HUD系统的例子是《战争机器》中的小部件。当玩家选择了一种新武器时这个小部件便会弹出来。但是却会因此破坏游戏的进程,让玩家不得不从原本沉浸的游戏世界中分散出多余的注意力。

玩家很少会在一些简单的行动中,如选择武器,遇到沉浸式的用户界面机制。如果玩家在游戏世界中能够找到一些真实的武器,那么游戏就不再需要呈现出非叙述世界提示帮助他们交换武器。

《魔兽世界》中拥有一个复杂且灵活的定制化用户界面,允许玩家能够根据自己的游戏体验进行优化。他们可以根据自己的需要选择各种内容去填充到屏幕上。

尽管一些游戏总是因为复杂的用户界面而遭到批评(游戏邦注:玩家认为没有了自定义选项他们便不可能获得竞争优势),但是我们必须牢记,《魔兽世界》是一款复杂的游戏,允许玩家使用各种不同的玩法。而用户界面的复杂性则是游戏复杂性的体现。

我们总是很难辨别一个组件是否属于非叙述世界组件。例如赛车游戏中的HUD的速度计是否属于非叙述世界组件?其实不是,它只是模仿汽车内部的真正速度计而设置于游戏中的一种组件。

空间组件

根据空间组件回答上述两个问题:

用户界面组件存在与游戏故事中吗?不是

组件存在于游戏空间吗?是的

在游戏世界中存在一些可视组件,但是它们却不属于游戏世界。游戏角色也不知道这些空间组件。例如在即时策略游戏中的单位周围的灵光选择环。它们主要用于提供关于游戏世界组件的额外信息,但是这些信息却不属于叙述内容。这些信息主要出现在玩家所聚焦的位置,从而避免HUD出现混乱布局。

一个典型的例子便是《魔兽争霸3》中的灵光设置。这些设置预示着游戏效果的合理性并且会影响到的游戏单位范围。另外一个例子便是《模拟人生》中游戏角色头上的图标。

《魔兽争霸3》中的选择环能够让玩家清晰地看到自己控制了哪些单位。而与此相比,在HUD的列表中做出选择明显困难多了——玩家很难辨别出哪些单位最靠近行动所发生的场所。

中间组件

根据中间组件回答上述两个问题:

用户界面组件存在与游戏故事中吗?是的

组件存在于游戏空间吗?不是

中间组件属于叙述内容,但是却不属于游戏世界。当出现在屏幕上渲染玻璃碎裂以及血滴四溅等画面时,这种组件便具有不错的效果,特别是与第四道墙相互作用时更加明显。

这些组件希望通过在屏幕上呈现明显的提示内容而让玩家感受到游戏中的现实性,就好似游戏真正在与玩家进行互动。《Killzone 2》中的血滴四溅便是典型的例子。同时我们还需注意的是这种用户界面组件同时也在通过降低可视性而影响游戏设置。

2D游戏中的叙事理论

至今为止我们都在讨论3D游戏中的叙事理论应用。然而这种理论也同样适用于2D游戏中。

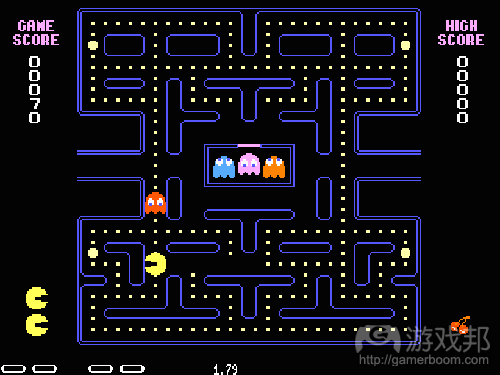

2D游戏也就是3D世界的平面模式。以《吃豆人》为例,其中也涉及叙述组件以及非叙述组件。在吃豆人的世界中,药丸,墙壁和幽灵都是属于叙述世界组件。而游戏得分和其它细节内容则是非叙述世界组件。

《Limbo》便是一款纯粹的叙述世界2D游戏。游戏中所有的用户提示内容都设置于角色所熟知的位置。游戏通过控制这种单纯的游戏内部体验而让玩家能够更加沉浸于游戏世界中。不论是背景还是前景,整个游戏世界都包含于玩家的体验中。玩家所涉及的任何内容都包含在游戏叙述中。

而2D游戏中的空间组件主要体现于游戏世界中的灵光或者指示器,如飞箭(尽管角色并不知晓这些内容),并且它们也不会影响到游戏中的目标物体。一个典例便是《Flight Control》中的路径和警示图标。

尽管我们很容易想象出2D游戏屏幕上的玻璃碎裂或血滴四溅的画面,但目前采用这种做法的2D游戏并不常见。

游戏邦注:原文发表于2011年2月2日,所涉事件和数据均以当时为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Video game user interface design: Diegesis theory

Posted by Dave Russell

Interface design is often one of the most challenging aspects of game development. There is a lot of information to convey to the player and little screen space with which to do it. When the interface is poorly designed, a good game concept can be reduced to a frustrating user experience.

There are several theories that can be used by designers to analyse a user interface and help them break down choices. The theory we will look at here is called diegesis theory. It is adapted from diegesis theory used in literature, film and theatre. Diegesis refers to the world in which the story is set, and hence it focuses on games as stories.

There are two concepts core to this theory: narrative and the fourth wall.

Narrative

Narrative is a message that conveys the particulars of an act or occurrence or course of events. In simple terms, it is the story the designer wishes to convey; be it the story of blocks falling from the sky which need to land in the right place (Tetris), or a journey through a strange land (Machinarium).

Not all elements of a game are part of the narration. For example, the game menus and the HUD, because the game’s characters are not aware of these elements. This does not mean these components do not support the narrative. For example, a futuristic game typically has GUI elements that also appear futuristic.

The fourth wall

The fourth wall is the imaginary divide between the player and the world of the game. In order for the player to immerse themselves in the game world, he needs to move through the fourth wall. The ease with which the player moves between the real world and the game world depends on the way the interface designer delivers information to the player.

Posting your latest game accomplishments on Facebook is an example of how a game extends beyond the fourth wall. To further delve into this concept, one should read Steven Conway’s interesting discussion of the fourth wall in games: A Circular Wall? Reformulating the Fourth Wall for Video Games.

Interface components

We can now ask ourselves two questions about any interface component:

Is the component part of the game story? (Is it part of the narrative?)

Is the component part of the game space? (Is it behind the fourth wall?)

Depending on the answers, we can classify the component into one of four classes: diegetic; non-diegetic; spatial; or meta.

The diagram below shows how the questions relate to the classes.

Diagram adapted from Gamasutra.

Diegetic Components

For diegetic components, we answer our two questions as follows:

Is the interface component in the game story? YES

Is the component in the game space? YES

Diegetic components provide the player with cues and information without distracting them from the narration of the world. These cues are something that the player’s avatar and other characters in the game world are aware of, and can interact with. This makes the experience more immersive and cinematic.

In Far Cry 2 an attempt is made to make the experience as diegetic as possible – there is no HUD. The use of numerous in-game gadgets and items allows the player to get information without referring to elements outside of, or superimposed over the reality of the game world.

While this is great for the immersion of the game, if it is not done correctly, it can have the opposite effect. For example, in the adventure game Grim Fandango the player is forced to search through their inventory one item at a time. This frustrating process breaks the player’s suspension of disbelief, and he pops back into reality.

Depending on the type of game you are designing, a completely immersive and realistic world may not be what you are looking to achieve, and this may in fact break the narrative of your story.

In Grim Fandango, the character’s head turns towards objects to indicate that they are interactive. Although it is perhaps a more realistic way to deliver information, the movement is awkward and unnatural. It is distracting and not as helpful as the glowing objects and mouse cursor changes traditional to adventure games.

Examples of diegetic interface

Designing diegetic interface components to replace common HUD elements requires a clever approach. Some examples follow:

In real time strategy games, diegetic components are elements such as the visual damage to units and buildings.

In Far Cry 2 the player can use a compass to help them navigate through the game world – far more immersive compared to the non-diegetic compasses that appear in HUDs of many other games.

In Dead Space, instead of providing a typical health bar overlay, the player’s health is indicated by the high-tech meter on the avatar’s suit.

Non-Diegetic Components

For non-diegetic components, we answer our two questions as follows:

Is the interface component in the game story? NO

Is the component in the game space? NO

We have all become very comfortable with the use of a heads up display (HUD) in games. This system provide us with key information in a fairly simple manner. If done correctly the player doesn’t even know it is there.

Some games, such as Gears of War, have a minimalist approach which limits the number of HUD items, while others, such as World of Warcraft, provide extensive HUD information.

An example a HUD being used poorly is the widget in Gears of War. The widget appears when the player selects a new weapon. This widget breaks the flow of the game, distracting the player from the world in which they have spent the last few minutes immersing themselves.

There are less intrusive user interface mechanisms one could use for a simple action such as selecting weapons. If the player is able to see the actual weapon in the game world there is little or no need to show a non-diegetic cue for swapping weapons.

World of Warcraft has a complicated but flexible and customisable user interface that allows players to optimise it to their personal play experience requirements. They can choose how much clutter fills the screen depending on their needs.

Although the game is often criticized for its complicated interface (by pointing out that the game cannot be played competitively without customizing it), it must be remembered that World of Warcraft is a complicated game that allows for many different types of play. The complexity of the interface is a result of the complexity of the game.

World of Warcraft has a rich user interface to support the vast amount of information given to the player. The interface is complex, because the game is complex.

It is not always clear whether a component is non-diegetic. Is the speedometer in the HUD of a racing game really a non-diegetic component? The speedometer is just a conveniently placed clone of the actual diegetic speedometer which is presumably inside the car.

The interface on the left is diegetic; the interface on the right is non-diegetic.

Spatial Components

For spatial components, we answer our two questions as follows:

Is the interface component in the game story? NO

Is the component in the game space? YES

These are components that are visualised within the game world but are not part of the game world. The game’s characters are also unaware of these spatial components. For example, the aura selection brackets around units in real time strategy games. They are used to provide extra information on a component in the world, although that information is not part of the narrative. The information is provided in the location on which the player is focused, reducing clutter in the HUD.

A good example of this are the auras in Warcraft 3. These indicate the gameplay effect that is currently in place and the range within which units will be effected. Another example are the icons that appear above the heads of characters in The Sims.

The selection brackets in Warcraft 3 immediately make it clear which units the player has control of. The brackets’ location in space makes selecting appropriate units much easier. Think of how difficult it would be the select them from a list in the HUD – it would be very difficult to see which units are closest to the action taking place in the game world.

Meta Components

For meta components, we answer our two questions as follows:

Is the interface component in the game story? YES

Is the component in the game space? NO

Meta representations are components that are expressed as part of the narrative, but not as part the game world. These can be effects that are rendered onto the screen such as cracked glass and blood splatters – effects that interact with the fourth wall are the most common examples.

These components aim to draw the user into the reality of the game by applying cues to the screen as if the game were directly interacting with the player. An example of this is the blood splatter on the screen used in Killzone 2. Note that this interface component also affects gameplay by reducing visibility.

Diegesis Theory in 2D Games

So far, we have only covered 3D games. The concepts we have discussed so far still apply to 2D games.

Think of a 2D game as a flattened representation of a 3D world. Take Pac-Man as an example. There is still the concept of a world, or narrative component, and components that are outside the narrative. The pills, walls and ghosts are all diegetic component of Pac-Man’s world. The scores and details around the game would are non-diegetic.

An example of a purely diegetic 2D game is Limbo. All user cues are presented within the world that the character perceives. The game leverages this pure in-world experience to help the user become immersed into the game. From the background to the foreground the entire world is part of your experience. There is nothing with which players interact that is not part of the narrative.

Spatial representations in 2D games are the auras or indicators, such as arrows, that are present in the game world, although the characters are unaware of them, and objects are unaffected by them. An examples of this are the paths and warning icons in Flight Control.

Although it is easy to imagine screen cracks and blood spatters against the screen in a 2D game, this is rarely done, and no examples of meta interface components come to mind. (If you think of anything, let us know in the comments!)(source:devmag.org)

下一篇:论述平台游戏的关卡设计过程

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号