解析互动游戏必须具备的基本原则

作者:Noah Falstein

互动娱乐是一种全新形式。但是它也正日渐成熟,并产生了其自身的一套基本原则。与其它创意形式一样,互动娱乐形式有时并不局限于这些基本原则。但如果创造者在探索新领域前不费心去学习这些基本规则,他们便会很容易踏进一些常见的误区。

“呈现”方式

创意写作课程的老师会侧重于讲述一些基本原则,而“呈现”便是其中一点。这个原则是在告诫学生,比起简单地告诉玩家发生了什么,应该明确地将角色所经历的事件呈现在他们面前。“写下你熟知的事物”是另外一个基本原理,是在告诉那些有志向的作家关注自己熟悉的事物。“冲突是戏剧的本质”也是一大原则,表示所有的戏剧化场景的核心都是冲突。

普遍原则

有一些基本原则似乎放之四海皆准。例如,我们很难去想象一个真正戏剧化场景中却没有任何冲突点,不论是在小说,剧本或者电脑游戏中。还有一些原则只适用于特定格式,如电影中的推拉镜头,即角色朝着摄像机慢慢靠近的表现形式能更好地调动观众的情绪。还有一些适合新人的规则,但是当他们真正掌握之后,这些规则便不再适用了。

有些原则适用于特定的亚学科,如智力游戏,教育类游戏,互动类视频游戏或者多人游戏等。如果你想要围绕悬疑小说创造一款游戏,你就需要去寻找撰写这类型文章的作者。你不可能只是雇佣一个只会写些关于银行投资内容的文案写手,你更不可能雇佣从未写过文章的歌手接手这项任务。

同等原则

在科学领域,有一种用于测试新理论的原则。根据这一原则,任何新发现的理论在靠近现有理论范围时,都应该屈服于这些已经被认可的理论。举个例子来说,相对论是用于解释牛顿物理学为何不能说明事物难以接近光速的原理,当时如果回到维多利亚时代,那时候的科学家们就会将这种新理论归入牛顿物理学理论中。同样地,量子力学是用于解释亚原子微粒的非直觉性行为,但是当用于考虑数十亿数万亿原子总体时,它们便只能遵循于我们原先所熟知的理论。

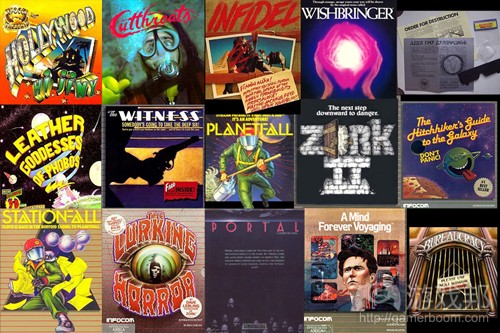

而在互动娱乐产业中又是怎样一种情况?就像是当一款互动软件游戏踏进一个直线型(也就是非互动)形式时,那么这个形式原先的规则也将继续适用。例如,Infocom早前的文本冒险游戏中总是带有许多描述性的文本段落。这些段落的效能能够通过标准的散文形式进行衡量。而文本冒险游戏中精心雕琢的描述也是完全按照小说家的标准。例外的是,这些段落中经常会出现关于进出某些区域的描写,而这便是互动功能的重要体现。

熟悉其它娱乐形式的人所创造出的互动作品总是会出现一些常见错误,即因为他们太过依赖于这种同等原则。例如,一位优秀的电影制作人可能认为,在故事的1、2个要点中添加适当的情节分支便能够制作出一款高质量的互动游戏。不幸的是,这与物理学家认为物理方程式同样适用于基于光速计算的宇宙飞船运行一样,是一种错误的观点。

明显的变化

规则能够适用于那些相类似的娱乐形式,这些形式的差别越大,其规则的调整幅度也会越大。比起从戏剧到散文或者从电影到戏剧的过渡,交互性对规则的变化要求更高。而关于这一要点,市场中有一个相对严谨的测试规则。如果一部互动作品是另外一种娱乐形式(如电影或小说),而你却将其装在CD中进行销售,你要如何鼓动用户购买它?印刷形式的小说更容易阅读,比起电脑更便宜且更方便携带,并且能够在书柜上存放30多年之久。比起同等互动作品,电影所需投入的制作预算更多,如果你选择到电影院看大屏幕,你需要支付7美元,而如果你选择租碟回家看,你就只需要3美元。所以为何用户会选择购买互动式版本?原因只有一个,那就是交互性本身就具有巨大的吸引力。

交互性是核心

一款互动娱乐作品必须具有乐趣,因为它具有交互性。唯一的例外便是以互动形式表现出来的多媒体元素,它们能够提供其它形式所没有的额外价值。互动娱乐能够将视频,文本和音频结合在一起,并赋予其价值。如果只是在有声书中添加一些插图和音效,或者在音频光盘中加入乐队的图片或歌词,它看上去似乎也仍然是一部具有基本交互功能的交互性产品——这正是为何许多互动作品失败的原因。它们刚开始可能只是一个剧本,一张图片或者一些基本概念,而交互性更像是随后才添加的内容。

有意义的选择

什么是交互性?这是与作出选择有关。对于一款优秀电脑游戏的简要描述是“关于获得一个明确目标的一系列有意义选择。”这个选择必须具有意义,从而才能体现出互动的乐趣。这也是为何简单的分支情节缺少乐趣的原因。重新折回故事主线的分支并不算真正的分支,因为这会让玩家快速掌握游戏的实际内容而对此感到厌烦。标准的传统冒险游戏中“选择对了继续前进,选择错了便死亡”的机制便是最早出现的有意义选择方法。但是遗憾的是,玩家虽然死亡了却还要继续游戏,顿时让这种死亡失去了意义,不过不管怎样,至少这种方法的方向是正确的。

心理学中有一个以小猫为对象的研究实验。让一半小猫自己在一个陌生的领域摸索,而另一半的小猫则放在小车上“推向”相同的领域。比起后者,这些以交互式行为摸索前行的小猫能够更快地熟知周边环境。同样的原则也适用于人类,如果我们是同样前往某个目的地的旅客,比起驱车前往,亲自摸索能够帮助我们更好地记住前进方向。

清晰的目标

为了让选择更有意义,玩家心中必须有一个明确的目标。首先,在掌机游戏或者电脑游戏开始的前几分钟,探索与发现便是目标。但是很快地,如果玩家失去了一个明确的目标,那么任何选择也就失去了意义,而游戏也会瞬间变得无趣,并因此让玩家感到挫败。探索是一个很棒的行为,是人类,甚至是所有哺乳动物的基本习性,就像是上点中提到的小猫。而如果我们能够在探索中明确目标,那么这种探索也会变得更加有趣。为了让互动游戏更有趣,你必须给予玩家一个明确的目标,并围绕着这一目标设定相关选择。

经济模式影响设计

这是所有想要进入新互动领域的人都应该牢记的重要规则。设计Saturn和PlayStation的互动娱乐具有细微差别,而设计PlayStation和电脑的互动游戏就具有显著的差别。PlayStation与在线游戏世界之间有一道巨大的鸿沟。互动娱乐领域涉及的经济模式非常广,而很多公司常常因为忽视了这一点而遭遇失败。这些经济模式的核心是一个基本方程式,即每个用户花费的钱等价于其享受到的游戏时间。而这些钱的支付方式将深刻影响着不同互动结构的可行性。

现实的幻觉

在不同娱乐形式中反复出现的一大原则便是幻觉的使用。当你在创造一种娱乐产品时,比起直接呈现现实本身,提供现实的幻觉会更合适。这就是为何在电影中一块燃烧的浮木能够散发出强烈的光线,照亮英雄的视野,挡开僵尸。这种表现根本不管现实中的浮木只会闷烧或者只是发出微弱光线的事实,因为如果只是遵照现实的表现就不好玩了!

在各种类型的模拟游戏中,这一原则特别重要。尽管有许多玩家热爱具有现实性的飞行模拟器游戏,还有大量玩家钟情于与现实情况不同的简单飞行和操作。人们会希望感受到的模拟体验是现实的,但同时他们也会参照自己内心对于现实的理解(来自于电视或电影中的所见所闻)而判别这种体验。一个极端的例子是,当把一个颇受欢迎的PC飞行模拟游戏带到街机游戏市场时,它失败了。玩家抱怨它太不切实际,并列出各种特征以比较它和早前飞行类街机游戏的区别。实际上,这款新游戏更具现实性,但对于一个投代币玩游戏的12岁男孩来说却未必是其想象中的飞行游戏。

结语

如果我们愿意花时间去学习互动性的基本原则,观察它们在不同类型和互动目标中的使用,我们便有可能避免一些常见错误并创造出高质量的游戏。只有学习过去的错误,我们才能避免重蹈覆辙。

游戏邦注:原文发表于1996年,所涉事件和数据均以当时为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Interactive “Show, Don’t Tell”: Fundamental Principles of Interactive Entertainment

by Noah Falstein

Pioneers

Interactive entertainment is a fairly new form. But it’s a form that is struggling with issues of maturity, not one still lost in infancy. Consequently some basic rules have been discovered, rules that grow out of the underlying principles of interactivity. Like other creative forms, it’s possible to transcend these basic principles. But like those forms, creators who don’t bother to learn the underlying rules before boldly setting out discover new territories are more likely to find themselves repeating old mistakes.

“Show, don’t tell”

Teachers of creative writing courses focus on a few basic principles. “Show, don’t tell” is a common one. It exhorts students to show their characters experiencing events rather than telling about what happened to them. “Write what you know” is another fundamental, warning aspiring writers to focus on familiar things. “Conflict is the essence of drama” is another, showing that all dramatic situations have conflict at their core.

Universal principles?

Some basic principles appear to be universal. For example, it’s difficult to imagine true drama without conflict of some sort, no matter whether it’s in a novel, a screenplay, or a computer game. Other principles apply only to a specific format, as in film where a tracking shot with characters walking towards the camera has more intensity than one where they walk alongside it. Still others are good rules for beginners to follow, but can be restrictive once real mastery is achieved. With interactive titles, it often pays to assume that rules may carry over from a different medium, but the likelihood of a rule being relevant is inversely proportional to how interactivity affects it.

Other principles apply to specific sub-disciplines, such as all puzzle games, or educational titles, or interactive stories that use video, or multiplayer games. If you wish to commission a mystery novel, you go to someone who’s written in that genre. You would be unlikely to hire a writer that has only written non-fiction about investment banking. You’d be even less likely to hire a singer who’s never written prose, just because you admire their singing.

The equivalency principle

Please forgive a brief excursion into the world of scientific theory. In Science, there’s a principle used to test new theories. To paraphrase, it states that newly discovered theories should reduce down to currently accepted theories as they approach the realm of those theories. For example, relativity helped explain why classical Newtonian physics broke down when considering things moving near the speed of light, but relativistic equations reduced to Newtonian equations as speeds dropped to the range that Victorian era scientists were comfortable with. Similarly, quantum mechanics explains non-intuitive behavior of subatomic particles, but when considered as a whole in the billions and trillions of atoms we’re used to dealing with, they behave just as we have grown to expect them to.

What does this have to do with interactive entertainment? Just that when an interactive software title treads into realms more closely resembling other linear (i.e. non-interactive) forms, the rules of those forms should still apply. For example, the old Infocom text adventure games had many descriptive passages of text. The efficacy of those passages could be measured by standards of prose, for that’s what they were. Well-written descriptions in a text adventure were well-written by the standards of a novelist. The exception was that they often included descriptions of the entrances and exits to the area described, the one feature critical to the interactive function of the description.

A common failure of interactive titles produced by people familiar with other forms of entertainment is to take this equivalency too far. For example, a good filmmaker might assume that making a good film and adding some plot branches at one or two key points of the narrative could produce a high quality interactive title. Unfortunately, this is like those classical physicists assuming their equations will still work as they apply them to a spaceship travelling at 99.9% of the speed of light.

A profound change

Rules can apply from one form of entertainment to another, as long as they’re similar. But the greater the differences between the forms, the more the rules change. Interactivity requires a fundamental change, more so than theater to prose, or even film to theater. The marketplace provides a rigorous test of this premise. If an interactive title is essentially another form of entertainment (like a movie or a novel) stuck on a CD, what incentive does the consumer have to buy it? The best novel can be read more easily in printed form, is cheaper and more portable than its PC equivalent, and will still be readable thirty years later if kept on a shelf. The best film had ten to a hundred times the production budget of its interactive equivalent, costs about $7 to see on a much larger screen, or about $3 to rent, and benefits from nearly 100 years of experience in production. So why buy an interactive version? There’s only one good reason. The interactivity itself must be compelling.

Interactivity is the core

The single most important principle of interactivity is as fundamental as the water a fish swims in, and as easily overlooked. An interactive entertainment title has to be entertaining because of, not in spite of, its interactivity. The only exception to this is the multimedia aspect of the interactive format, which can provide an added value not found in other forms. Interactive entertainment can provide video, text, and audio all linked together, and that has some value. But as is seen by the very limited market for books on CD with some added illustrations and sound effects, or for audio CD’s with some pictures of the band and lyrics, it’s still undeniably the interactivity itself that is the fundamental feature of an interactive product. That one fact helps explain why so many interactive titles have failed. They started with a screenplay, or a picture, or some other basic concept, and interactivity was added in as an afterthought farther down the line.

Meaningful choices

What is interactivity? It’s about making choices. A simple capsule description of a good computer game is “A series of meaningful choices to reach a clear goal”. The choices must be meaningful for the interactivity to be enjoyable. That’s why simple branching plotlines just aren’t interesting (another favorite mistake of linear story.tellers new to interactivity). Branches that fold back into the main storyline aren’t really branches, and the player will catch on quickly to the fact and become bored. The standard old-style adventure game format of “make the right choice and proceed, make the wrong choice and die” was a first-pass way of making the choices seem more meaningful. Unfortunately the necessity of continuing on past death robs that death of meaning, but at least it is a step in the right direction.

A psychological study was once conducted with very young kittens. Half of the kittens were allowed to explore a strange area on their own, the other half were “driven” through the same area in little carts. The kittens that explored interactively learned their way around much faster than the other kittens. The same principal applies to humans — most of us have learned that we remember directions much better when we’ve driven a car to a new place than if we were merely passengers on the same journey.

Clear goal

In order to give meaning to choices, the player must have a goal in mind. At first, for the first few minutes of a console or PC game, exploration and discovery is goal enough. But quite soon, if the player is not given a specific goal, the choices cease to have meaning, and the title becomes boring, or worse, frustrating. Exploration is good, it’s a fundamental human, even mammalian habit, as was seen with the kittens. But exploration becomes even more exciting, and certainly more satisfying, when we have a goal. To make an interactive title more fun, give the player a clear goal and make the choices along the way relevant to achieving the goal.

The economic model affects the design

This is an important rule for anyone trying to break into a brand new field of interactive entertainment (or even one that is just new to their experience). There’s little difference in designing interactive entertainment for the Saturn and the Playstation. There’s a larger difference in designing for the Playstation and the PC. And there’s a wide gulf between the Playstation and an online world. The field of interactive entertainment covers a wide range of economic models, and many a company has gone belly-up ignoring that fact. At the heart of all of them is a basic equation of hours of entertainment per consumer dollar spent. The way those dollars (or tokens, or electronic debits) are spent strongly affects the viability of different interactive structures. It’s a subject worthy of an entire book, so suffice it for now to say that new economic structures demand rethinking interactive design.

Illusion of reality

One principle that carries over from other forms of entertainment is the use of illusion. When you’re entertaining, it’s more important to give your audience the illusion of reality than it is to give them reality itself. That’s why a piece of burning driftwood in a film gives off enough light for the hero to see and fend off the zombies. It doesn’t matter that a real piece of wood would just smolder, or at best burn dimly. That wouldn’t be fun!

This principle is particularly important with simulation games of all sorts. Although there’s a market for ultra-realistic flight simulators, there’s a larger one for airplanes that fly more easily and work better than in real life. People still want to think that their simulated experience is realistic, but they’re measuring the experience against their internal perception of reality, which has been shaped by countless hours of TV and films. An extreme example of this was the relative failure of a popular PC flight simulator when brought to the arcade market. Players complained it was unrealistic, citing the very features that distinguished it from earlier generations of arcade flying games. The new game was in fact more realistic, but to the twelve-year-old boys dropping their tokens in, it wasn’t their idea of flying.

Conclusions

If we take the time to learn the basic principles of interactivity, to see how they apply to different genres and interactive venues, we can avoid common mistakes and create quality titles. Only by learning from the errors of the past can we avoid repeating them.(source:theinspiracy)

上一篇:解析《CityVille》房屋建造的经济学原理(1)

下一篇:过于强调平衡性或降低游戏趣味性

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号