详析游戏制作和游戏设计的5个视角

作者:Tadhg Kelly

数年以来我们都通过游戏玩法和故事这两个相对视角来解析游戏及其制作者,尽管这种单维范围较为简单,但显然是不恰当的。

在讨论游戏时,我采用的不是两个而是四个视角。每个视角都代表着我经常从制作者身上看到的假设和倾向,它们之间的相互关系构成了一副有趣的图表。

视角和坐标轴

视角是种认知、情感或知觉偏见,会影响到信息的接收、理解和前后关系。在政治、宗教、哲学和艺术领域存在诸多视角,游戏制作者也有他们自己的视角。他们对于玩家或奖励在游戏中的职责有着不同的想法。有些人认为结构化目标是最重要的,有些人认为应当将玩家表现放在首位。

开发者审视游戏时所使用的视角会影响到他们对有价值或无价值工作的衡量标准,我想这就是多数开发者在职业生涯中往往只专注于某种类型游戏的原因所在。因而,视角可以奠定游戏(游戏邦注:或游戏中的模式)及其开发者的类别。

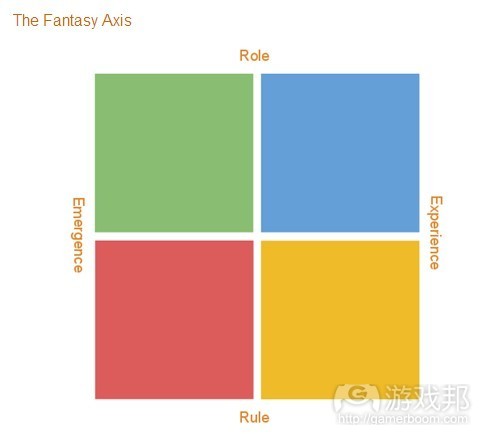

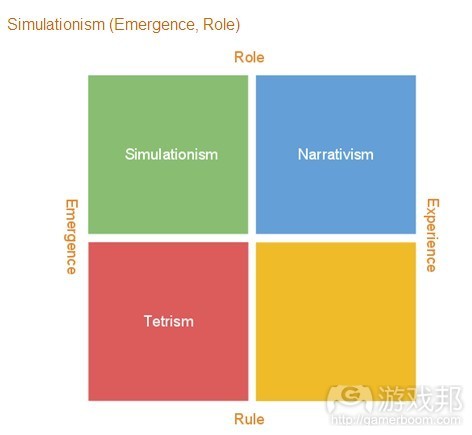

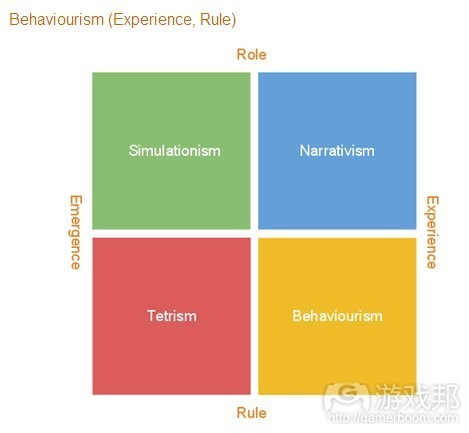

在游戏玩法和故事的双视角模型中,两者间的关系往往用坐标轴来描述。同样,我用两套坐标轴来描述4种视角,形成2 X 2的格子。每个坐标轴代表1种兴趣,所以每个视角都由两种兴趣构成。这种做法类似于Richard Bartle对玩家类型的描述,结果图表清楚地显示出4种视角,每种视角都有产生诸多变种的空间。

这两个坐标轴是:框架轴(突发和经验),想象轴(角色和规则)

框架轴

框架轴呈现的是不确定或确定结果的重要程度,也就是游戏设计偏向突发性或经验玩法。

游戏的框架便是其机械层次。游戏框架中的所有东西都可以归结为双重信息(游戏邦注:如盟友和敌人、危险和安全、胜利和失败等)。

如果某个框架存在高程度的发现内容,包括那些连游戏设计师也没有预见到的发现,那么这种框架便倾向于突发性。玩家可以在游戏中采用异乎寻常的战略和创新行动,开发者也参与到发现过程中。突发性框架的目标系统是,用有限的动作和规则创造出近乎无限的结果。

如果框架传播的是具有预测性的情感参与,那么这种框架便更倾向于经验。设计师对游戏进行计划、衡量和评估。它将玩家置身于较为熟悉的游戏世界中,并不关注玩家的创新意识。经验框架的目标系统是,操控玩家并将其导向富有吸引力的结果。

规则健全便很有可能创造出突发性玩法,因而偏爱突发性的开发者更趋向于设计引擎简洁的框架,将游戏的所有可能性容纳其中。经验设计更多关注的是游戏中的各个时刻。在这种框架中,互动的范围有限,但游戏可以推动玩家做出关键选择,并使用场景效果来吸引玩家的注意力。

多数游戏不会单独选择突发性或经验框架中的一种。多数游戏会将这二者融合起来,然后在整体上偏向其中一种。

想象轴

游戏吸引玩家进入另一个世界,并赋予他们在规定范围内做出决定性动作的能力。但是,游戏世界的呈现方式各不相同。想象轴区分的是抽象与逼真、贫瘠与丰富,游戏是赋予玩家重要的角色,还是将玩法的规则置于玩家角色之上。

如果游戏框架可以视为其机械层次的话,那么想象便是位于框架之上的艺术、音效、文字、动画等创造性层次。想象是游戏世界的特性,可能是简单图标化,也可能写实风格。

趋向于规则的想象显得正式和明确。框架是可见的,玩家只是单纯在操纵游戏内容而已,游戏中的改变由一只无形的手来控制。极端重视规则的游戏可能只使用数字、卡牌和形状之类的元素,使用屈指可数的特色元素来定义游戏环境。

趋向于角色的想象意图将框架隐藏起来,好似将游戏构建成风景。虽然玩家在游戏中仍然是通过动作来获胜,但玩家是在令人信服和精心制作的背景中开展动作,背景尝试赋予玩家某种身份。玩家的角色成为游戏世界中角色的一部分。

因而,想象强大的游戏会在特征、视觉元素、音乐、特殊效果和语言上花大量的时间。它们会尽可能地减弱框架的表现力,让玩家从艺术的角度欣赏游戏。

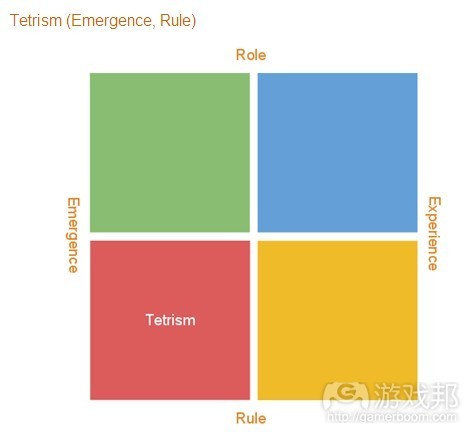

俄罗斯方块主义(突发,规则)

俄罗斯方块主义指创造简洁的游戏动态,这种动态有持续性的趣味性,玩家需要长期时间方能精通于游戏。这种游戏的灵感来源于许多简单的经典游戏,比如象棋、桥牌、纵横填字谜等。

俄罗斯方块主义游戏颇为形式化,以少数固定的动作为基础,限制性规则引导游戏向不可避免的结局发展(游戏邦注:比如时间、分数、速度或难度提升)。适度的俄罗斯方块主义化游戏往往很有吸引力(游戏邦注:比如许多独立或休闲游戏),这些游戏的框架都是突发类型的。

俄罗斯方块主义游戏测试的是玩家的技术和战略。它们的游戏动态可以很容易地描述,比如将方块分类、拼词、踢球或移动棋盘上的棋子。游戏中可能有简单的故事,也有可能毫无故事性可言。但是,游戏中潜藏的战术和策略极为丰富。

俄罗斯方块主义的价值在于,它专注于发挥游戏最基本的吸引力。俄罗斯方块主义游戏往往会在新兴平台上以简单的设计震惊世界,俄罗斯方块主义者总是渴望能够出现新的设备和平台,给他们带来创造新颖动态的机遇。但是,他们不只对新平台感兴趣。即便在PC之类的较老平台上,每年依然会出现许多新俄罗斯方块主义游戏。

俄罗斯方块主义者往往将自己视为最纯粹的游戏开发者。他们追求的是找到能够引领新一代游戏诞生的创新或发明,因而他们往往很重视历史上的经典游戏及其所获得的成功。这使他们觉得自己好似与当今游戏开发文化脱节,后者的做法是花大量时间将俄罗斯方块主义者所认的为应当简洁和普遍化的内容复杂化。他们对免费游戏之类的做法也持有消极态度,因为他们认为此类游戏的设计有失公平性。

俄罗斯方块主义者的代表包括:宫本茂(《超级马里奥兄弟》)、Alexey Pajitnov(《俄罗斯方块》)、Jeff Minter、Kyle Gabler和Ron Carmel(《World of Goo》)、Andreas Illiger(《Tiny Wings》)和Adam Atomic(《Canabalt》)。

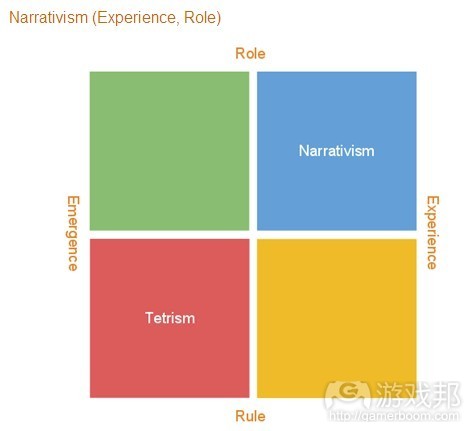

叙事主义(经验,角色)

叙事主义指使用游戏来传达故事化体验,玩家在游戏中起到积极的作用,引导游戏结果的显现。其灵感来源于文学、电影、戏剧和其他叙事艺术,电子游戏成了这种形式的新继承者。

叙事主义者想要让玩家从游戏中感受到超越胜利喜悦以外的东西。她希望玩家能够真正关心游戏中的角色,体验到角色的失落、希望、悲伤和恐惧等感觉。她希望玩家能够感受到自己是这场戏剧中的英雄。叙事主义游戏的目标在于取得美学上的连贯性。它们的开发者会花费大量时间来创造游戏世界的地点、人物和音效。丰富性、真实性和制作价值是游戏的重要内容。背景故事、角色特征和主题也是如此。

普通叙事主义游戏会适度结合突发游戏玩法和发现机遇,游戏结果的可预测性相对较强。这样,游戏就具有一定的故事感。强势的叙事主义游戏从故事感转变到故事讲述,试图让玩家认同游戏角色,限制游戏的突发场景,更多采用经验框架。这些游戏往往难以理解,却极容易精通,这便导致游戏产生了意料之外的乏味感。最极端的情况是,叙事主义项目完全放弃了“游戏”想法,成为非游戏的娱乐形式。

叙事主义者面临的最大问题可能是业界的认同。他们往往将自己视为艺术家,希望全球文化舞台能够平等地看待他们的游戏和电影。有些人甚至认为,未来游戏将取代其他形式的艺术,因为从某种程度上来说,互动艺术比所谓的被动艺术“更好”。类似于制度学派的人,他们本质上都希望艺术世界能够认同游戏确实是种艺术形式。

叙事主义者代表包括:David Cage(《暴雨》)、David Jaffe(《战神》)、Tim Schaeffer(《冥界狂想曲》和《疯狂世界》)、Auriea Harvey和Michael Samyn(《故事中的故事》)、Jesse Schell(《全景探秘游戏设计艺术》)和Jason Rohrer(《The Passage》)。

模拟主义(突发,角色)

模拟主义指创造逼真可信的游戏世界,供玩家探索、实验和发现。其灵感来源于人工智能和软件本身无限的可能性。

模拟主义游戏由复杂规则和健全系统来支撑,但是它们的开发者却不希望那些系统可见或带有限制性。对于意图创造(游戏邦注:或重新创造)出色彩斑斓世界的游戏而言,胜利、任务、形式化目标和情感导向这些内容显得格格不入。模拟主义者希望尽可能地让玩家自己确定目标,感受自己选择带来的惊讶和乐趣。

模拟主义游戏会给玩家分配个强势却又很容易描述清楚的角色,然后围绕其构建整个游戏世界,让角色显得更加真实。角色的类型多种多样,比如飞行员、冒险家、城市或国家的统治者、火车驾驶员、巫师、上帝、主题公园所有者、足球经理和邪恶天才等。他们专注于让玩家亲身体验复杂效果,让玩家意识到所有的动作都能够产生后果。模拟主义游戏还鼓励创造性玩法,玩家可以将游戏视为创作的画布。

普通模拟游戏中通常有部分形式化结构和方向,尤其是在游戏的早期阶段。这种类型的游戏中,最好的是将真实模拟同虚假模拟融合起来。就整体效果来看,虽然游戏的真实性有所下滑,但玩家更易于上手。

但是,在强势模拟游戏中,所有内容都是突发的,内容由程序生成,其目标在于创造无限的可能性。因而,模拟主义最大的困境就在于其不透明性。游戏世界变得过于复杂,角色过于模糊不清,复杂效果过于微妙使玩家难以理解,这样使得玩家往往不会佩服设计师的天赋,却产生相反的感觉:游戏过于随机性,显得不公平,这会影响到玩家在游戏中的情绪。

模拟主义者往往认为自己类似于调查类科学家,处在边缘化的领域。他们相信模拟是电子游戏的要点,艺术和游戏的个人化玩法是完全相同的两个事物。因而,模拟主义者时常会对那些欺骗和操控玩家的游戏感到失望。

模拟主义者代表包括:Will Wright(《模拟城市》、《模拟人生》、《孢子》)、Peter Molyneux(《上帝也疯狂》、《黑与白》)、David Braben(《Elite》、《Kinectimals》)、Sid Meier(《文明》)、Todd Howard(《上古卷轴》)、Markus Persson(《Minecraft》)、Chris Delay(《数码战争》)、Andrew Stern和Michael Mateas(《面具》)和Kristoffer Toubourg(《EVE Online》)。

行为主义(经验,规则)

行为主义指将玩家视为愿望的集合体,创造满足这些愿望的系统。其灵感来源于行为和动机心理学,所有的游戏均被视为挑战、预期和奖励引擎。

行为主义者注重游戏的心理吸引力,由此来吸引玩家,鼓励玩家在情感上认同游戏的结果。他们使用重复性动作来完成循环和给予奖励。对循环结束的期盼和奖励能够对人类思维产生强大的影响,引发乐观主义的感觉。以往的奖励形式是金钱,渠道包括赌博机和彩票等。新的奖励形式包括分数或玩家可用来实现其他目标的虚拟商品。

行为主义的特点便是指标。行为主义者尽可能地用指标衡量玩家,测试小改变后衡量其结果。这意味着,行为主义者会谨慎地使用突发性元素。突发性通常难以直接衡量,对行为主义者来说,任何不能衡量的东西都无法有效可靠地进行提升。

因而,行为主义者是这些人群中最保守的人。他们认为较好的方法是,复制成功游戏并将其改善,或者改造其他游戏(游戏邦注:该游戏主题可能与目标主题不同),而不是从新开始制作内容。这种倾向和可预测方法正是行为主义者受到投资者青睐的缘由,但也正是这种方法导致其游戏的用户价值较低,形成真正的忠实用户或粉丝文化的可能性很小。

行为主义以某种方式同游戏制作伦理相抗争,这是4种视角中较为独特的。赌博、沉迷和欺诈是严肃的社会问题,但行为主义者比起其他人来似乎更易于接近这些内容。但是,行为主义游戏也存在积极的一面,其开发者相信游戏可以引导社会变迁和自我升华。

他们认为自己才是下个游戏时代的主宰者,将其他视角视为主观或过时做法。然而,当玩家将目标放在找出最优战术,只关心外在的驱动力(游戏邦注:比如奖品)而忽略游戏背后更大的理念时,行为主义游戏设计(游戏邦注:尤其是游戏化)似乎就变得毫无意义。正因为此,其他视角支持者(游戏邦注:尤其是俄罗斯方块主义者)视行为主义为欺骗和邪恶之物。

行为主义者代表包括:Jane McGonigal(《Reality is Broken》和《SuperBetter》)、Brian Reynolds(《FrontierVille》)、Dave Maestri(《Mob Wars》)、Mark Pincus(Zynga)、Brenda Braithwaite(《Ravenwood Fair》)、Amy Jo Kim(《Consultant》)、Gabe Zichermann(游戏化传播者)、Michael Acton-Smith(《Moshi Monsters》)和Sebastian Deterding(研究者和设计师)。

第5视角

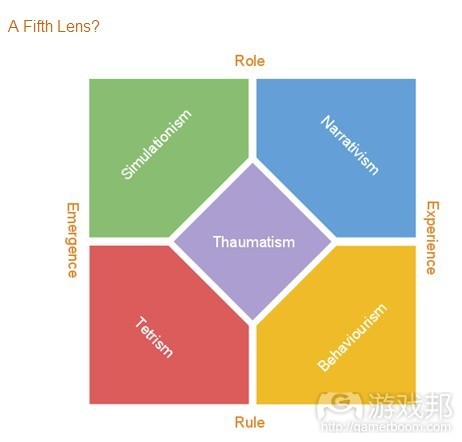

本文是以中立态度看待这些视角,各种视角中都有可借鉴之处,但最令人印象深刻的电子游戏往往位于多个透镜的临界之处。

《超级玛丽奥64》偏向于俄罗斯方块主义,但是也部分涉及到模拟主义、叙事主义和行为主义。《模拟人生》是款模拟主义游戏,但是部分层面属于俄罗斯方块主义和行为主义,游戏中还带有叙事感。《最终幻想7》属于叙事主义游戏,但是在团队构建和探索层面上属于模拟,战斗和某些可选经济玩法中带有的是突发战术。

对粉丝而言,这些都是传奇游戏。综合使用多种视角可以产生协同作用,但我觉得事情没有这么简单。各视角中的元素也有可能相互影响,使得整体效果下降。上述游戏的愿景和创新存在不定因子,这个X因子不存在于任何轴上。

本文用“惊奇”(游戏邦注:thauma,柏拉图曾指出thauma是哲学家的标志,是哲学的开端)来描述这些游戏的独特魔力,所以或许可以将认同X因子重要性的视角称为“惊奇主义”。

对惊奇主义者来说,游戏本身就是艺术。游戏设计存在需要遵循的界线(游戏邦注:多数情况下由玩家而非设计师来定)和准则。惊奇主义位于所有视角之上,并借鉴了其他所有视角的元素,并根据自己的需要对其加以改良及整合。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Four Lenses of Game Making

Tadhg Kelly

For years it’s been apparent that interpreting games and their makers through the opposed lenses of gameplay or story is inadequate. Such a one-dimensional spectrum breeds false oppositions (fun-or-art?) while either ignoring many games that don’t fit or reinterpreting them so they fit badly. The spectrum is too reductive and, while it is easy to summarise, it leaves out too much context.

Rather than talking about games in terms of two lenses, I use four (potentially five, but I’ll come back to that). Each represents a common set of assumptions and predispositions that I often see in makers, and there are correlations between them which makes for an interesting (though perhaps deceptively symmetric) diagram.

This post is long, but I’d like to take you through each in turn. I think you’ll find it useful.

Lenses And Axes

A lens is a cognitive, emotional or perceptual bias which affects how information is received, understood and contextualised. In politics, religion, philosophy and the arts there are many lenses, and game makers have their lenses too. They have different ideas on the role of the player in the game, or the role of rewards. Some believe that structured goals matter, others that player self expression is king.

The lens through which a game maker sees games tends to affect the kind of work that they consider worthwhile or worthless, and I suspect is why most makers tend to concentrate on one type of game over their career. Lenses therefore describe categories of games (or modes within games) as well as their makers.

In the dual-lens model of gameplay-or-story the relationship between the two is often described as an axis. Similarly, I describe lenses by two axes, leading to a 2×2 grid. Each axis represents an interest, and so each lens represents a combination of two interests. This is similar to Richard Bartle’s description of player types, and the resulting graph shows four clear lenses, with room inside each for wide variations.

They are:

the Frame Axis (Emergence-Experience)

the Fantasy Axis (Role-Rule)

The Frame Axis

The Frame Axis is about the importance of uncertain or certain outcomes, and therefore whether the game is designed toward emergent or experient play.

The frame of a game is its mechanical layer. It is the levers and environment of the game stripped of all context and aesthetic concerns. Everything in the frame of the game boils down to binary information (allies/enemies, dangerous/helpful, win/lose etc) and the frame is the only part of a game that the play brain understands.

A frame is more inclined toward emergence if it permits a high degree of discovery, especially of the kind that the game’s designers never foresaw. Unusual strategies, innovation and creativity are enabled, and in some ways the game maker feels as much a participant in the discovery of the game as the creator of it. The objective of developing an emergent frame is a system in which a limited set of actions and rules produces a near infinite set of outcomes.

A frame is more inclined toward experience if it delivers predictable emotional engagement. The game is planned, measured and assessed for impact. It pulls players along in well understood patterns, and is unconcerned with player innovation. The objective of developing an experient frame is a system that manipulates players and leads to set piece outcomes that they find compelling.

Robust rules are most likely to produce emergent play, and so makers who like emergence tend to design frames with elegant engines that encompass all possibilities. Experient design is less concerned with overall robustness and more on moments. They often have frail frames, meaning that they have limited ranges of available interaction, but smooth over this by pushing the player toward key decisions, playing on their sense of anticipation and using theatrics to draw their attention.

Most games are neither wholly emergent or experient. The majority use a bit of both, favouring one overall.

The Fantasy Axis

Games draw players into other worlds and empower them to take decisive action within their confines. However worlds vary wildly in how they are presented. The Fantasy Axis is about abstraction versus fidelity, nakedness or richness, and whether the game gives the player a strong contextual role, or regards role as secondary to the formal rules of play.

If the frame of the game is its mechanical layer then the fantasy is the creative layer of art, sound, text, numina, animation, fiction and so forth that sits on top of the frame. Fantasy gives the game world an identity, from the simple and iconographic through to lush realism. In encourages empathy, and communicates to the player culturally as well as intellectually. It might be realistic or stylised, hand-crafted or generated procedurally, narrative or open-ended.

Fantasies which tend toward rules are formal, literal and unambiguous. The frame is highly visible and the player simply plays as herself, the invisible hand that causes change. Strongly rules-oriented games might only use elements like numbers, cards, squares and shapes and have only a few distinctive terms that define conditions in the game.

Fantasies which tend toward roles want to hide the frame in favour of painting a landscape. While the player is still taking action to win, she does so within a convincing and elaborate context that tries to define an identity for her. Her role is a job description, a part of a cast within a world, even possibly a persona.

Strongly fantastical games therefore tend to spend a lot of time on characterisation, visual elements, music, voice-overs, special effects and language. They de-emphasise the frame as much as possible (sometimes too much) in order to induce the art brain to believe.

Tetrism (Emergence, Rule)

Tetrism is about creating neat game dynamics that are consistently fun and inviting the player to master them over a long term. It is inspired by the elegance of many classic games, like chess, bridge, crosswords or soccer.

Tetrist games are formal, based around a few defining and highly extensible actions and bounded by rules which bring the game toward an inevitable conclusion (such as time, points, speed or increasing difficulty). Although moderately tetrist games are often charming (such as many indie or casual games), the frame is both clear and emergent, and the win conditions are usually victories.

Tetrist games are tests of skill and strategy. Their game dynamics are often easily described, such as sorting blocks, making words, kicking a ball or moving pieces on a board. Story is perfunctory or non-existent. Optimal tactics and strategy are high.

The value of tetrism is its focus on the kind of engagement that the play brain thrives on. Tetrist games are usually the ones that break out on new platforms to stun the world with simple genius and tetrists are always keen to see what new devices bring opportunities to create novel dynamics. However they are not just motivated by new interfaces: Even on older platforms like the PC there are many new tetrist games every year.

Tetrists often think of themselves as the most pure kind of game maker. They aspire to find that unique innovation or invention that will spawn a generation of games, and so they are often keenly aware of (and overshadowed by) past games and their successes. This leaves them feeling left behind by a game development culture that spends a great deal of time on complicating what tetrists feel should be elegant and universal. They also tend to react negatively to ideas such as free-to-play economics because of the perceived issues of fairness.

Possible examples of tetrists might include Shigeru Miyamoto (Mario), Alexey Pajitnov (of Tetris fame), Jeff Minter, Kyle Gabler and Ron Carmel (World of Goo), Andreas Illiger (of Tiny Wings) and Adam Atomic (Canabalt).

Narrativism (Experience, Role)

Narrativism is about using a game to impart a storied experience in which the player takes an active role and develops sympathy toward its outcomes. It is inspired by literature, cinema, theatre and other narrative arts, and places videogames as an inheritor of those forms.

The narrativist wants the player to feel more than just the joy of winning. She wants him to care, on a personal level, about what happens to the characters in the game, and to experience sensations of loss, hope, and sadness as well as thrills. She wants the player to feel as a dramatic hero in his own play. Narrativist games aim to be aesthetically coherent. Their makers spend a lot of time creating the place, people, sights and sounds of their world. Richness, authenticity and production values matter. Back story, characterisation and theme likewise.

Moderately narrativist games combine mildly emergent gameplay and opportunities for discovery with outcomes that are fairy predictable. The result is storysense. Strongly narrativist games move away from storysense into storytelling, attempting to characterise the player and limiting emergence in favour of experience. They often become opaque or are easily mastered, leading to unintended boredom. At their most extreme, narrativist projects abandon the idea of ‘game’ altogether and becomes a non-game, like a virtual promenade or amusement ride.

Possibly the biggest issue for narrativists is validation. They often consider themselves to be artists and aspire for their games to be taken as seriously as cinema on the global cultural stage. Some even believe that games will one day eclipse or eat all other forms of art and contrast interactive art as somehow ‘better’ than so-called passive art. Like all institutionalists, they are essentially looking to an art world to confer legitimacy upon them.

Possible examples of narrativists might include David Cage (Heavy Rain), David Jaffe (God of War), Tim Schaeffer (Grim Fandango, Psychonauts), Auriea Harvey and Michael Samyn (Tale of Tales), Jesse Schell (The Art of Game Design) and Jason Rohrer (The Passage).

Simulationism (Emergence, Role)

Simulationism is about creating an endless and authentic world in which a player can explore, experiment and discover. It is inspired by artificial intelligence, holodecks and the infinite possibilities of software itself.

Simulationist games have complex rules and robust systems underpinning them, but their makers do not like those systems to be visible or bounded. Wins, tasks and formal goals sit uncomfortably within a game that tries to create (or recreate) a plausible world, as does direction of emotion. A simulationist wants the player to be as self-directed as possible, to feel the delight of surprise or meaning on their own terms.

Simulations cast the player in a strong, but easily described, role and then build the entire world around making that role feel real. Roles can be as varied as pilot, adventurer, ruler of city or state, rail driver, wizard, god, theme park owner, football manager, evil genius and so on. They focus on making complex effects tangible to the player and conveying a sense of consequences for all actions. Simulationist games also tend to encourage creative play, with players using the game itself as a canvas.

In moderate simulation there is usually some amount of formal structure and direction to the game, especially through its early stages. The best games of this type include a blend of true simulation with simulacra (faked simulation), with the overall effect that the game is less than real but more easily grokked.

However in strong simulations everything is emergent, procedurally generated and aims for infinite possibility. Simulationism’s biggest pitfall is therefore opacity. Worlds can become too complex, roles too indistinct and complex effects too subtle for players to perceive, and far from appreciating the genius of the engine powering this world the player often has adverse reactions: the game becomes random, unfair or frustrating.

Simulationists often consider themselves to be at the cutting edge, like research scientists. They believe that simulation is the point of videogames, and that the art and individuated play of games are one and the same. Therefore the truth of the game is what matters most, and simulationists are usually disappointed by games that they regard as faking, manipulating or spoon-feeding players.

Possible examples of simulationists might include Will Wright (Sim City, The Sims, Spore), Peter Molyneux (Populous, Black and White), David Braben (Elite, Kinectimals), Sid Meier (Civilization), Todd Howard (The Elder Scrolls), Markus Persson (Minecraft), Chris Delay (Darwinia), Andrew Stern and Michael Mateas (Facade) and Kristoffer Toubourg (EVE Online).

Behaviourism (Experience, Rule)

Behaviourism is about considering the player as a collection of desires and creating systems that satisfy those desires. It is inspired by behavioural and motivational psychology, and considers all games as challenge, anticipation and reward engines.

Behaviourists model their games on psychological hooks that open loops, draw engagement and encourage emotional attachment to outcomes. They use repetitive actions to complete those loops and deliver rewards. The anticipation of a loop’s end, and the reward, has a powerful effect on the human mind and can engender feelings of optimism. In older forms that would mean money, such as a slot machine or a lottery. In newer forms it sometimes means points or virtual goods that the player will find useful toward another goal.

The big revolution of behaviourism is metrics. Behaviourists measure everything that they possibly can about their players, test small changes and then measure their outcome. However this means that behaviourists tend to be wary of emergence. Emergence is generally hard to directly measure, and to the behaviourist anything that cannot be measured cannot be reliably improved.

So behaviourists tend to be the most creatively conservative of all lenses. They consider it better to copy a successful game and improve upon it, or adapt another game (perhaps with a different theme) rather than create from scratch. This sort of lean and predictable approach is why behaviourists are the darlings of the investment scene, but also why their games tend to be lower value on a per-user basis than all other kinds. They are far less likely to engender true loyalty or a fan culture.

Behaviourism struggles with the ethics of game making in a way that other lenses do not. Gambling, addiction and exploitation are serious social issues and behaviourist games skirt closer to them than any other kind. On the positive side, many behaviourist game makers believe that games can be agents of social change and self improvement.

They think of themselves as the next generation, characterising other lenses as subjective or backward. Yet strong behaviourist game design (particularly gamification) tends to flounder when faced with the play brain’s ability to figure out dominant tactics and only care about extrinsic motivators (i.e. prizes) while ignoring wider ideals. This more than anything is why makers from other lenses (particularly tetrists) tend to regard behaviourism as either deluded or evil.

Possible examples of behaviourists might include Jane McGonigal (Reality is Broken, SuperBetter), Brian Reynolds (FrontierVille), Dave Maestri (Mob Wars), Mark Pincus (Zynga), Brenda Braithwaite (Ravenwood Fair), Amy Jo Kim (Consultant), Gabe Zichermann (Gamification evangelist), Michael Acton-Smith (Moshi Monsters) and Sebastian Deterding (researcher and designer).

A Fifth Lens?

Regular readers of What Games Are know that I often talk about the boundaries of games, like:

Storysense, not storytelling.

Ground your gameplay but don’t idealise founderworks.

Avoid meta-games.

And the Techthulhu dream.

In a sense this blog advocates a centrist position that says that there are lessons to learn from all lenses, but also that the most memorable videogames often come from the space where lenses cross rather than the far corners.

Super Mario 64 tends toward tetrism but has influences of simulationism, narrativism and behaviourism. The Sims is a simulation, but aspects of it are tetrist and behaviourist, and there is a sense of narrative. Final Fantasy VII is narrativist, but with simulation in the form of team building and exploration, emergent tactics in combat and some optional economic grinding too.

To their fans, each is a legendary game, clearly thaumatic. Using some of each lens can be synergistic, but I think there’s more than simple cross-over effects at work. Elements which pull on each other can just as easily lead to dysnergy (less than the sum of its parts), which nobody wants. There’s an x-factor of vision, invention and creative voice in each of these games, and that’s not something that sits easily on any axis.

Since this blog invented the word thauma to describe the uniquely magic of games, I might as well call the lens that believes in the importance of x-factors thaumatism.

To the thaumatist, games are an art as they are, not as they might be. There are boundaries to work with (mostly set by players, not designers) and principles to follow. Somewhat experient, somewhat emergent, a bit governed by rules and influenced by role, thaumatism sits above other lenses, blatantly borrows from all of them and unifies them with intent. And that somehow translates into magic.

Is it a lens as such, or just a way of describing how game makers can draw from the founderworks of every lens to create masterworks? That’s for you to decide. (Source: What Games Are)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号