分析称开发商仍有望在Facebook平台获得成功

作者:AJ Glasser

随着Facebook平台头号游戏开发商Zynga进入IPO阶段,有些人猜测Facebook游戏市场已达巅峰,其成长性已经不值得开发商再为该平台发布新社交游戏。

通常来说,这个结论的产生基于3种猜想。第1种,随着美术和设计质量要求以及用户获取成本不断提升,再加上Facebook Credits交易抽取30%费用,制作Facebook平台游戏已经很难再获得可观的盈利。第2种,游戏的巅峰期只能持续两个月时间,随后不可避免会开始出现用户量下滑的情况,这使得许多人认为投入到游戏中的所有资源和预先展开的营销都只是为了赌这两个月的时间。第3种,为了吸引市场中数量庞大的用户群体(游戏邦注:也就是经常说的“35岁家庭主妇”)和那些难以捉摸的鲸鱼用户(游戏邦注:每月在游戏中花费数百美元的玩家),所有的Facebook游戏都必须拥有特定的某套功能。

第1种猜想已经被今年的许多社交游戏所证实,其中包括《The Sims Social》、《CastleVille》和《Gardens of Time》等高生产价值游戏。而且Facebook切断了使早期游戏迅速成长的病毒性渠道,与2009年相比,现在开发商已更依赖广告来进行营销。这使得开发商现在需要花比之前更多的精力和金钱来制作游戏和营销游戏,影响到游戏的总体盈利。但是,第2和第3种猜想仍还没有事实依据。

根据Inside Virtual Goods收集到的数据以及AppData流量跟踪服务多个流量样式研究结果,我们了解到不少社交游戏的成长时间可能是发布后的三个月。但是,我们也发现了某些值得注意的案例,有些游戏的初始成长阶段超过3个月,而有些游戏的初始成长并非在游戏发布之后。根据Facebook收集到的数据和许多游戏开发者展开的自主调查,我们还知道了社交游戏的主要用户并非35岁或者更老的妇女,而是18到35岁的人群,男女兼有。

简单地说,与去年相比,进入Facebook游戏平台的确将面临更多的困难,但是这并不意味着社交游戏市场已经停止成长。

开发商无法成为Zynga的原因

Zynga是个占尽天时地利的开发商,其成长得益于Facebook平台上形成急速病毒性传播的客观环境。该开发商以收获作物或玩扑克等简单且富有吸引力的游戏机制为基础构建起社交游戏帝国,然后迅速地俘获人才和知识产权,通过发布新游戏的方式来维持成长,并升级技术来改善用户体验。

但是现在已不是2009年,Facebook平台已经发生改变。首先,社交游戏开发商使用病毒性渠道的难度增加。其次,Facebook已经扩张至国际市场,社交游戏潜在用户开始对游戏的质量、内容和盈利方式有一定的期望。最后,现在免费游戏开发商在Facebook平台上所面临的竞争形势更加严峻。

两年前,Zynga的潜在竞争对手可以在Zynga发布城市建设游戏或餐厅模拟经营游戏的数周内推出同题材仿制产品,而这种情况下两款游戏均可以获得成长(游戏邦注:Zynga的成长通常会更快些,这归因于公司的扩展性交叉推广网络和Facebook的些许帮助)。但是现在,这已经不再是种可行的成长战略,因为在社交游戏行业中,农场、城市建设、犯罪、宠物和餐厅等许多主流Facebook游戏题材已经拥有大量产品。有些公司推出的新游戏只是“新瓶装旧酒”,改变了原有游戏的外观,或改变场景或角色,内在游戏概念并没有发生变化,这种做法现在也无法取得成效。

盈利的方法

尽管开发商们无法取得如同Zynga般的成长,但至少他们有希望像Zynga那样盈利,甚至还有可能实现更可观的盈利性。无论是哪个开发商,以下核心方程式总是成立的:用户终生价值(游戏邦注:下文简称“LTV”)>每用户安装成本(游戏邦注:下文简称“CPI”)=可盈利游戏。虽然CPI不受开发商掌控,因为病毒性和广告取决于Facebook上适用的推广渠道,但是开发商可以直接控制用户的LTV,通过与Zynga此前做法有所不同的方式来盈利。

根据Zynga在9月份发布的季度财报所示,公司“平均每用户盈利”为5美分左右,这便是每用户每天购买的虚拟货币量。Zynga在游戏中销售的多数虚拟商品是额外的装饰性道具和完成任务、建造物体的材料。这些道具的价格从1货币单位到50货币单位不等,平均每货币单位的价格介于10到14美分之间。

注:Zynga的CPI也相对较低,因为他们已经积累了数量庞大的玩家,无需花费资金来获取更多玩家。

但是,正如我们之前说过的那样,这个市场处在不断改变中。该平台上还有其他类型的游戏,比如战略题材,用户付费购买防止被其他用户攻击的道具,或者让他们在战斗中取得明显优势的道具(游戏邦注:比如减少生产战斗单位的建筑的修理时间)。在这些类型的游戏中,道具的价格比Zynga得道具平均价格更高(游戏邦注:比如有些炮塔需要7美元,而装饰性横幅只需要5美元),但是由于游戏本身的性质差异,玩家却更愿意支付更多金钱来购买这种道具。当玩家的基地被全盘摧毁,立即重新建成需要小额金钱而普通建造需要1天时间,那么玩家很有可能投入金钱。即便是休闲和模拟题材游戏也在尝试添加新类型虚拟商品,增加游戏模式和互动,比如花5美元购买游戏券就可以在1周时间内无限玩《Tetris Battle》,《Sims Social》以12美元的价格出售可供玩家休息的床铺道具。

照这种情况来看,现在Facebook上应该有每用户平均日盈利1美元左右的游戏,而且许多此类游戏的日活跃用户超过10万。那么就会产生一个问题,在上述盈利方程式中,CPI数值有多大?

Facebook的首要作用:抑制成本

Facebook很清楚,自己对于影响平台上社交游戏成功的作用要超过开发商本身。除了创建和维护平台,Facebook也是新游戏曝光和成长的首席仲裁者,现在它还增添而来一项责任——通过平台货币Facebook Credits的力量来维持游戏经济。因为Facebook Credits的盈利来源于游戏内的交易,而且游戏开发商需要购买Facebook广告,因而社交游戏也是Facebook盈利的重要组成部分。

注:Facebook并未公布公司盈利中各部分的比例,但是我们可以估算。假设Facebook Credits今年的盈利为12亿美元,其中30%来源于社交游戏,也就是3.6亿美元,Facebook总盈利约为40亿美元,那么游戏内置交易占公司总盈利比例为9%。

Facebook也意识到自己的过失,平台早期放任社交游戏开发商滥用病毒式传播渠道,那些只关注盈利的应用及滥用病毒渠道的现象使Facebook在2009年和2010年禁止了这类工具的使用。这导致开发商社群的惊恐,Facebook强制性地将Credits整合到所有的应用中使他们更加无所适从。Facebook已经尝试一系列措施抚平他们的创伤,通过新的功能和曝光算法弥补已经失去的病毒性渠道。

为了平台将来的成长,Facebook似乎已明白自己需要通过广告和有机方法来让社交游戏获得成长。在广告方面,Facebook近期将页面上展示的广告总数从4个增加到6个,而且引进了赞助广告和推荐。在有机成长和曝光方面,Inside Network前主编Eric Eldon曾指出Facebook已经做出了改变,社交游戏通知的数量相对于2011年夏天和秋天的情况来说有所增加。Facebook似乎还尝试根据玩家的当前游戏偏好来推荐新游戏,比如当我们经常玩某款解谜游戏时,平台会向我们展示好友的解谜游戏活动,而不是向我们展示他们的战略游戏活动。最后,通过发布手机平台的方式,实现智能手机和PC的跨设备体验游戏,Facebook使其开发商更容易进入手机市场,在那里获得更好的成长。

如果没有开发商在广告上的投入,单靠Facebook的这些改变可能不足以让新社交游戏取得我们之前提到的日活跃用户上10万的成功。但是Facebook仍然希望社交游戏能够成功,我们有理由期待该公司2012年会在有机成长方面采取更多措施,这可以降低用户获取成本。

Facebook的次要作用:支持新游戏类型

就游戏本身来说,Facebook能够做的就是改善供开发商使用的配套工具。这包括装饰和小范围功能双方面,比如成就和高细节化游戏故事内容,甚至对平台做出较大的基础结构改变,使之可以支持新游戏类型、超本土化游戏和在平台下运行同时深度整合Facebook Connect的游戏。比如,两年前根本不可能想到Facebook能够支持同步多人竞技游戏。现在,我们已经可以在Facebook看到这种游戏和第一人称射击游戏,甚至还有赛车游戏。明年或者数年后,Facebook甚至可以支持大范围的同步MMO角色扮演和战斗游戏,亚洲和欧洲市场的表现已经证实这些类型的免费游戏是可行之举。我们也期望Facebook Connect整合能够变得更为先进,使开发商可以同时在Facebook和自己的站点上发布游戏,类似Zynga的Project Z计划。

成长情况

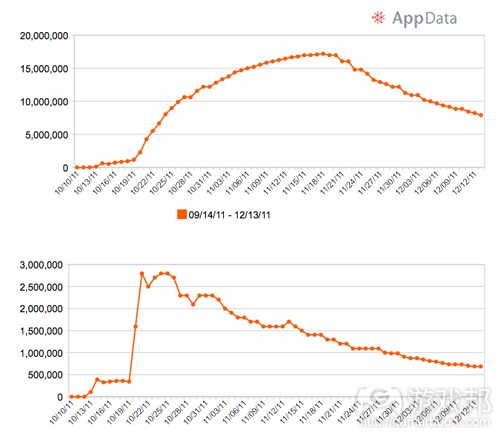

随着社交游戏行业的成熟,我们将越来越少看见类似下图的成长轨迹:

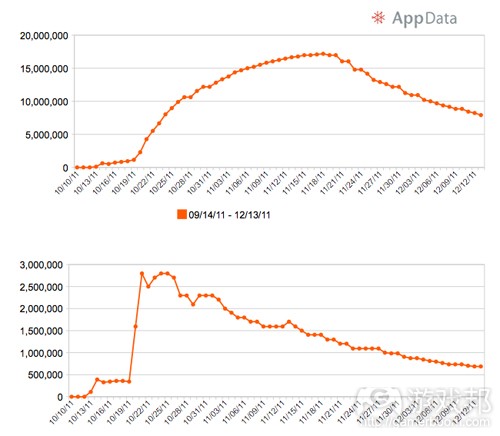

希望可以看到更多像这样的成长:

依赖Facebook的社交游戏业务仍然还有可能存在,但这取决于开发者在合理预算下构想、发布和盈利游戏的能力以及Facebook平台自身的发展。并非所有的开发商都能够成为Zynga,但是仍有可能出现较受用户欢迎的新产品。

相对比上市开发商来说,私有开发商有更大的自由度在新兴市场中尝试新颖做法。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Can Games Still Succeed on Facebook?

AJ Glasser

With Facebook’s star game developer Zynga in the middle of its IPO process, some speculate that the Facebook games market has reached its peak and no longer showing enough growth to justify betting on launching new social games for the platform.

This conclusion is generally based on three types of assumptions. The first is that games are now too expensive to make for Facebook to bring in healthy profit given that the level of quality in art and design has risen along with user acquisition costs, plus a 30% fee taken out of Facebook Credits transactions. The second is that games only have a window of two months to hit a peak reach with users before an inevitable decline begins, which leads many to believe that all a game’s resources and pre-loaded marketing are banking on a single point in time. The third is that all Facebook games must have a predetermined set of features in order to appeal both to the broader market — which is perceived in the coarsest terms as a “35-year-old housewife” — and to the unpredictable whales (players who spend hundreds of dollars in-game per month as opposed to just a few dollars at most).

The first can be backed up by some examples from the 2011 season of social games — which included high production value titles like The Sims Social, CastleVille and Gardens of Time — as well as by the fact that Facebook cut back on the viral channels that made early games grow so quickly, thus forcing developers to rely more on advertising now than they did in 2009. This creates a situation where developers spend more now on creating games and advertising them than they previously needed to, which eats into profits. The second and third assumptions, however, are harder to substantiate with empirical evidence.

We know based on data collected by Inside Virtual Goods and multiple case studies of traffic patterns in our AppData traffic tracking service, for example, that many social games do see the most growth in their first three months. We also have, however, notable cases where that initial growth period exceeded three months or the initial growth period didn’t begin until well after the game had launched. We also know based on data collected by Facebook and by several game developers in self-funded surveys that the primary audience for social games isn’t necessarily women 35 and older, but men and women from 18 to 35.

In short, yes, there are higher barriers to entry on the Facebook games platform now than there were a year ago. But that doesn’t mean the market for social games has stopped growing.

Why We Can’t All Be Zynga

Zynga is a developer that had the right idea at the right time with the right set of favorable circumstances to produce massive viral growth on the Facebook platform. The developer built its empire on simple, compelling game mechanics like harvesting crops or playing poker and then set about acquiring talent and intellectual property at a rapid rate to sustain that growth with new game releases and technology upgrades to improve the user experience.

But it’s not 2009 anymore and the Facebook platform has changed. For one thing, there’s less access to viral channels for social game developers. For another, Facebook is expanding in international markets where the potential audience for social games already has expectations of quality, content, and monetization practices. Lastly, there is more competition both on the Facebook platform and off now than there ever has been for free-to-play game developers.

Two years ago, a potential Zynga rival could release a city-building game or a restaurant industry sim within weeks of Zynga’s own entries into those genres and both games would experience growth (Zynga usually seeing quite a bit more thanks to its extensive cross-promotion network and possibly some help from Facebook). This is no longer a viable growth strategy for social games as many of the major Facebook genres — farming, city-building, crime, pets, and restaurants — are well and thoroughly saturated. This also goes for companies that make “reskin” versions of their own game, changing the setting or characters of a game that is still the same game concept underneath the hood.

How We Still Make Money

While developers can’t expect to grow like Zynga, they can at least hope to monetize like Zynga and potentially even monetize better. Whether it’s Zynga or not, a developer is always looking at the core equation: User Lifetime Value (LTV) > cost per install (CPI) = profitable game. While CPI is largely out of the developer’s control because virality and advertising depends on what channels Facebook makes available, the LTV of a user is something that developers can impact directly by monetizing their games in ways that differ from what Zynga has done.

Based on regulatory filings, we know that Zynga made over 5 cents in “average bookings per user,” which is the amount of virtual currency purchased by a user in a day, in the financial quarter ended in September. Most of Zynga’s virtual goods sales in the bulk of its games are based on premium decoration items and components for completing quests or building objects. These items go for anywhere from one or two premium currency units to 50 at between 10 and 14 cents per currency unit.

Note: Zynga also has a low CPI because they’ve already amassed a large network of players and don’t need to spend money to gain more.

As we say, however, the market is changing. There are game types out there, like the strategy combat genre, where users are paying for item types that provide protection from other users, or a distinct combat advantage (e.g. speeding up repair times on structures that produce combat units). In these games, the price of the item is more expensive than Zynga’s average item price (maybe $7 for a turret compared to $5 for a decorative banner), but players are more compelled to spend it based on the nature of the game itself. Monetization in these games is particularly compelling in cases where a player’s base can be completely destroyed, but instantly rebuilt for a small fee (say, 30 cents) at multiple re-builds a day. Even casual and sim titles are experimenting with new virtual good types that add game modes or interactions — like game tickets that allow for a week’s worth of unlimited play in Tetris Battle for $5 or Sims Social bed items for sleep and sexual interactions that go for $12 or more.

At rates like these, it’s not hard to imagine that there are games on Facebook right now that regularly make around or just above $1 per user per day — and many of these with more than 100,000 daily active users. The big question is, how high is the CPI variable in the profit equation?

Facebook’s Role First Role: Keeping Down Costs

Facebook is well aware that it’s responsible for the success of social games on the platform more so than the developers themselves. Aside from creating and maintaining the platform itself, Facebook is also the primary arbiter of discovery and growth for new games and now it has the added responsibility of preserving game economies through the strength of its platform currency, Facebook Credits. Based on Facebook Credits revenue gained via in-game transactions and Facebook ads purchased by game developers, social games could make up a significant portion of Facebook’s revenue.

Note: Facebook couldn’t be reached for comment on the breakdown of revenue, but for the sake of a rough sketch, assuming that Facebook Credits revenue hits $1.2 billion this year and 30% of that was collected from social games (even though Credits wasn’t officially mandated until July) and that Facebook hits the estimated $4 billion in revenue, that’s $360 million — or 9% of revenue just from in-game transactions.

Facebook is also aware that it created a monster by allowing social game developers near complete freedom in the early days of the platform, once opened to third party developers. Spam apps and abusive use of the viral channels led Facebook to cut back on those tools dramatically in 2009 and 2010. This led to consternation in the developer community, which only swelled when Facebook made Credits integration mandatory across all apps. Facebook has tried to smooth things over through developer outreach programs and restoring some of that lost virality through features like the canvas app ticker and via new algorithmic discovery that sometimes surfaces social game activity to non-gamers in the site-wide live app ticker.

As for future growth on the platform, Facebook seems to understand that it needs to do more to produce growth for social games both through ads and organic means. On the ad side, Facebook recently increased the total number of display ads on pages from four to six and has introduced sponsored ads and recommendation surveys into the canvas app ticker. As for organic growth and discovery, former Inside Network Editor Eric Eldon points out over on TechCrunch that Facebook has been making changes that expose a higher volume of social game notifications than we saw over the summer and fall of 2011. The social network also seems to be experimenting with exposing new games based on players’ current game preferences — for example, showing us a friend’s arcade puzzle game activity when we frequently play a particular puzzle game instead of showing that same friend’s strategy combat story. Lastly, by launching a mobile platform that allows for cross-device play between smartphones and PCs, Facebook has made it easier for developers to enter the mobile market and find more growth there.

On their own, these changes might not be enough to get new social games to that arbitrary 100,000 daily active user mark mentioned above without developers having to spend on ads. But Facebook still wants to social games to succeed, we can expect to see it doing more in 2012 to spark organic growth, which in turn offsets the cost of user acquisition.

Facebook’s Second Role: Supporting New Game Types

As for what Facebook can do for games themselves, it’s all about improving the tool set available to developers. This means both cosmetic and small-scale features, like achievements and highly detailed game story content, as well as larger infrastructure changes that can support new game types, hyper-localized versions of games, and games that run off-platform while leveraging a deep Facebook Connect integration. For example, two years ago, it would have been impossible to imagine Facebook supporting a synchronous competitive multiplayer game. Now, we have those and first-person shooters, and even rudimentary racing games. We also see support for apps in new emerging languages that goes beyond mere translation and into actual game adaptation. In the next year or so, it looks like Facebook could even support large-scale synchronous MMO role-playing and combat games, which are both proven free-to-play genres in international markets like Asia and Europe. We also expect Facebook Connect integrations to become more sophisticated in a way that allows developers to simultaneously launch games both on Facebook and on their own sites — similar to what it sounds like Zynga is planning with Project Z (a.k.a. Zynga Direct).

Where Does the Growth Go? To the Right

As the social games industry matures, we’ll see fewer growth trajectories like this:

And hopefully begin to see more like this:

A sustainable social games business that hinges largely on Facebook is indeed still possible, but it depends on the ability of the developer to conceive, launch, and monetize a game on a reasonable budget and on the evolving nature of the Facebook platform itself. We can’t all be Zynga, but that’s probably the best news of all. A private developer has more freedom to try new things in an emerging market than a publicly traded one. (Source: Inside Social Games)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号