多人游戏平衡理论第1部分:术语定义

作者:Sirlin

平衡多人竞赛游戏绝非易事。本文主要先定义若干术语,让读者把握此系列文章的主要内容。(请点击此处阅读第2、第3部分)

首先就是术语。下面就来看看游戏平衡性和深度的相关定义:

若游戏向玩家呈现的众多选择都具有可行性,那么其就具有平衡性——尤其是在资深玩家的高级别体验中。

——Sirlin,2001年12月

若资深玩家已研究、练习游戏几年、几十年或几百年,游戏对其而言依然具有策略趣味性,那么此多人游戏就颇具深度。

——Sirlin,2002年1月

此平衡性的定义非常到位,但可行选择背后依然隐藏2个概念。一方面,我的意思是游戏不会退化到只有一个策略,另一方面,我的意思是说战斗游戏具有众多人物选择,或即时战略游戏具有众多竞赛选择,且其中的多数人物/竞赛都具有可行性。我们姑且将第一、二个概念分别称作可行选择和初始选择的公平性(游戏邦注:简称公平性)。

可行性选择:向玩家呈现众多富有意义的选择。出于深度考虑,他们通常基于特定背景,令玩家能够运用策略做出这些决策。

公平性:技能相同的玩家具有相同的获胜机会,即便他们可能基于系列不同选择/动作/人物/资源等开始游戏。

可行性选择

我们需要在玩法中向玩家呈现系列可行选择,这就是Sid Meier所说的游戏由系列有趣决策构成。

若某熟练玩家能够持续通过某操作或策略打败其他资深玩家,那么这款游戏就缺乏平衡性,因为其中缺乏足够可行选择。这类游戏也许具有众多选择,但我们只关心那些富有趣味的内容。若众多选择只达到同个目的,或无所收获,或输给上述主导操作,那么它们就不是有意义的选择。它们阻碍内容,给游戏带来糟糕复杂性:令游戏难以掌握,失去趣味复杂性。

出于深度考虑,我们希望玩家能够基于某些原则决定这些富有意义的选择。若手边游戏是单回合剪刀石头布游戏,玩家就没有理由优先选择某种出法,所以我们很难在此融入策略。但《街头霸王》类的游戏能够基于瞬间决策:你决定阻塞、投掷或升龙拳,或者《Magic: the Gathering》类的游戏能够基于单一决策:是否采用反制法术。这些例子乍看之下同剪刀石头布模式类似,但基于比赛情境的决策存在众多细微差别,其中各玩家面对众多关乎未来举措的线索。在《街头霸王》和《Magic》中,玩家能够基于某原则优先进行某操作,我们希望游戏包含不止一个的可行选择。

关于深度,我们希望富有意义的决策能够基于对手的操作。不妨想象下《星际争霸》做出这样的调整:玩家无法进行互相攻击。他们所能进行的操作就是花5分钟创建自己的基地,然后基于所创建内容计算分数。这款游戏包含众多决策,存在系列获胜路线,但由于这些决策纯粹关乎优化问题(游戏邦注:更像是解决谜题,而非体验游戏),因此造就的是款肤浅的竞争性游戏。幸运的是,在实际的《星际争霸》中:玩家决定创建内容时需考虑对手会建造什么。

虽然我们认为游戏应融入大量可行选择方能算具有平衡性,但需创造玩家决策情境及决策要涉及对手操作的要求主要同深度相关。但这些内容颇值得特别说明,因为在我们平衡游戏的同时应试着提高游戏深度,而非降低此标准。

公平性

这里的公平性指的是所有玩家都具有相同获胜机会,虽然他们可能会基于不同选择开始游戏。在《街头霸王》中,各角色具有不同运动方式,在《星际争霸》中各竞赛具有不同单元,在《魔兽世界》中,各角逐团队具有不同级别、技能和工具。所有这些不同选择组合应存在公平性。

我要特别指出的是,我只是谈论游戏开始时玩家所面临的选择。这是不容忽视的差异。在游戏开始后呈现的选择无需具有公平性。不妨想象下这样的第一人称射击游戏:8种武器在地图上的各位置生成,其中2种非常杰出,3种还行但算不上一流,剩余3种非常糟糕,但比2款一流武器中的某款强大。

这是否就是理论角度的游戏平衡性?也许就是如此,其符合目前所述的所有标准。游戏设计师需确保所有武器具有相同威力,但只要各武器在正确情境中依然属于可行选择,他就无需考虑这点。此构思不错:设置2个玩家争相角逐的武器,若干还不错的中等武器,以及某些主要让玩家对抗强大武器的薄弱武器。决定控制地图哪部分位置涉及众多策略元素,而何时转变武器则取决于对手的操作。

相反,基于此方案设计的8角色战斗游戏就缺乏平衡性,因为无法满足公平性标准。玩家在游戏开始前决定战斗游戏的角色,但他们在玩法中选择第一人称射击游戏模式的武器。玩家所处角色劣于对手角色属于不公平情况。

让玩家基于不同选择开始的游戏很难获得平衡,因为他们需要让那些选择存在公平性,同时在玩法中呈现众多可行选择。

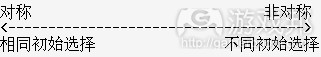

对称&非对称游戏

所谓的对称游戏是指所有玩家基于系列相同选择开始游戏。所谓的非对称游戏是指玩家基于系列不同选择开始游戏。不妨将此术语看作某区间,而非两个端点。

在区间左侧,具有代表性的游戏包括国际象棋。在国际象棋中,双方都基于16颗棋子开始游戏,唯一的差别是白棋优先。由于存在不同起始条件,我们很难说国际象棋具有100%对称性,但其非常接近此标准。若国际象棋是你看过的唯一一款游戏,你也许会觉得黑白双方的体验方式完全不同;白棋控制节奏,而黑棋做出相应反应。有许多书籍专门介绍黑棋一方如何进行体验。若将范围锁定全球范围的众多游戏,我们会发现国际象棋的双方同《星际争霸》的两种竞赛,《街头霸王》的两种角色或《Magic: The Gathering》的两种牌组相比则相似度很高,很难进行区分。

游戏的初始条件越丰富,其就越接近区间的右边。所以这里的非对称性是用于衡量游戏初始条件的多样性。这并非什么严密科学,所以我们就无法通过什么特定公式确定游戏在此区间所处的位置,但这是非常通俗易懂的概念。

下面就来看看几个例子。《星际争霸》包含3种不同竞赛,所以它靠近区间的右侧。也就是说,虽然3种竞赛各不相同,但其数量不算多,我们不应将其放至非常左边。战斗游戏能够融入众多体验方式各异的角色,倾向融入比其他多人竞赛游戏更多的非对称元素。

也就是说,单人战斗游戏的非对称性变化幅度很大。例如,《VR战士》是款非常杰出和深刻的战斗游戏,但其角色的丰富性相比其他战斗游戏就低很多。相比《街头争霸》(游戏邦注:其中某些角色具有能够延伸至整个屏幕的导弹或武器,或者能够飞行环绕整个球场),《VR战士》的角色模版都非常相似。再来就是《罪恶装备》,你也许从未听过这款战斗游戏,其丰富性胜过我所知晓的所有同类作品。某角色能够创造复杂形式的台球,另一角色能够同时控制两个角色,而另一角色则具有有限数量的硬币,这能够强化角色的其他操作,同时解锁强化操作的奇怪漂浮薄雾。仿佛所有角色都来自不同游戏,但它们却能够公平地进行竞争。《罪恶装备》始终处在区间的右侧,因为它包含不同起始选择(角色),而且选择量非常大(超过20)。

《Magic: The Gathering》在构造格式(其中玩家将预先制作好的牌组带入比赛中)上也相当不对称。适合牌组的丰富性非常惊人,比赛通常包含各种威力相当的不同牌组,虽然其玩法各不相同。

第一人称射击游戏倾向朝对称一侧靠拢,通常在开始时向玩家提供相同选择,除生成地点外。记住在《军团要塞 2》的玩法中,玩家可选择不同武器,甚至改变级别,这算不上非对称的体现。此外,双方具有非对称目标的第一人称射击游戏通常会转换玩家位置,让他们在其他回合中角色互换,这样整体比赛才具有对称性。

我们已描述若干游戏在上述区间的粗略位置,记住这并非衡量游戏质量的方式。若你最喜欢的游戏出现在左边(对称一侧),这并不意味着这些游戏不好。若你喜欢《星际争霸》胜过《罪恶装备》,你无需因《罪恶装备》“更不对称”而感到沮丧。此区间旨在让我们获悉游戏起始选择的差异性,而非游戏深度或趣味。

无论游戏出现在此区间的哪个位置,其依然需要提供众多在玩法中起到平衡作用的可行选择。除此之外,游戏越靠近区间图的左侧,就越需要平衡不同起始选择的公平性。

游戏邦注:原文发布于2010年10月17日,文章叙述以当时为背景。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Balancing Multiplayer Games, Part 1: Definitions

By Sirlin

Balancing a competitive multiplayer game is not for the faint of heart. In this article I’ll define the terms that will let us know what we’re talking about in the first place, then in the second and third articles, I’ll pretend that we have some hope of solving the wicked problem of game balance and I’ll explain techniques to do it. Then in the fourth article, I’ll try to impress upon you what deep trouble we’re really in.

First, the terms. Let’s start with balance and depth as defined by the Philosopher King of game balance:

A multiplayer game is balanced if a reasonably large number of options available to the player are viable–especially, but not limited to, during high-level play by expert players.

–Sirlin, December 2001

A multiplayer game is deep if it is still strategically interesting to play after expert players have studied and practiced it for years, decades, or centuries.

–Sirlin, January 2002

This definition of balance is pretty good, but there are two concepts hiding inside that term viable options. On one hand, I meant that the game doesn’t degenerate down to just one tactic, and on the other hand, I meant that if there are lots of characters to choose from in a fighting game or races to choose from in a real-time strategy game, many of those characters/races are reasonable to pick. Let’s call the first idea viable options and second idea fairness in starting options, or just fairness for short.

Viable Options: Lots of meaningful choices presented to the player. For depth’s sake, they are presented within a context that allows the player to use strategy to make those choices.

Fairness: Players of equal skill have an equal chance at winning even though they might start the game with different sets of options / moves / characters / resources / etc.

Viable Options

The requirement that we present many viable options to the player during gameplay is what Sid Meier meant when he said that a game is a series of interesting decisions (a multiplayer competitive game, at least).

If an expert player can consistently beat other experts by just doing one move or one tactic, we have to call that game imbalanced because there aren’t enough viable options. Such a game might have thousands of options, but we only care about the meaningful ones. If those thousands of options all accomplish the same thing, or nothing, or all lose to the dominant move mentioned above, then they are not meaningful options. They just get in the way and add the worst kind of complexity to the game: complexity that makes the game harder to learn yet no more interesting to play.

For the sake of depth, we also hope that the player has some basis to choose amongst these meaningful options. If the game at hand is a single round of rock, paper, scissors against a single opponent, there is nearly no basis to choose one option over the other so it’s hard to apply any kind of strategy. And yet a game of Street Fighter might be decided by a single moment when you choose to either block, throw, or Dragon Punch, or a game of Magic: the Gathering might be decided by a single decision to play a Counterspell or not. These examples at first glance look like the rock, paper, scissors example, but the decisions take place inside the context of a match that has many nuances where each player is dripping with cues about his future behavior. In Street Fighter and Magic, the player does have basis to choose one move over the other, and more than one choice is viable, we hope.

Also for depth, we prefer if the meaningful choices depend on the opponent’s actions. Imagine a modified game of StarCraft where no players are allowed to attack each other. All they can do is build their base for 5 minutes, then we calculate a score based on what they built. There are many decisions to make in this game, and it might have several paths to victory, but because these decisions are purely about optimization–more like solving a puzzle than playing a game–they make for a shallow competitive game. Fortunately, in the actual game of StarCraft, you do need to consider what your opponent is building when you decide what to build.

While we require many viable options to call a game balanced, the requirement about giving the player a context to make those decisions strategically and the requirement that the decisions have something to do with the opponent’s actions are really about depth. They’re worth pointing out though because we should attempt to increase the depth of the game as we balance it, not decrease it.

Fairness

Fairness, in the context I’m using it here, refers to each player having an equal chance of winning even though they might start the game with different options. In Street Fighter, each character has different moves, in StarCraft each race has different units, and in World of Warcraft, each arena team has different classes, talent builds, and gear. Somehow, all of these very different sets of options must be fair against each other.

I want to stress that I am only talking about options that you’re locked into as the game starts. That’s a very important distinction. Options that open up after a game starts do not necessarily have to be fair against each other at all. Imagine a first-person shooter with 8 weapons that spawn in various locations around the map. Two of these weapons are the best overall, 3 are ok but not as good as the best weapons, and the remaining 3 are generally terrible but happen to be extremely powerful against one or the other of the 2 best weapons.

Is this theoretical game balanced? It certainly might be, meaning that nothing said so far would disqualify it. A designer could decide that he wants all weapons to be of equal power, but he need not decide that as long as each weapon is still a viable choice in the right situation. It might be fine to have two powerful weapons that players compete over, a few medium power weapons that are still ok, and some weak weapons that allow players to specifically counter the strong weapons. There could be a lot of strategy in deciding which parts of the map to try to control (in order to access specific weapons) and when to switch weapons depending on what your opponents are doing.

By contrast, a fighting game with 8 characters designed by that scheme is not balanced because it fails the fairness test. Players choose fighting game characters before the game starts, but they pick up weapons in the first-person shooter example during gameplay. Being locked into a character that has a huge disadvantage against the opponent’s character is unfair.

Games that let players start with different sets of options are inherently harder to balance because they must make those sets of options fair against each other in addition to offering the players many viable options during gameplay.

Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Games

Let us call symmetric games the types of games where all players start with the same sets of options. We’ll call asymmetric games the types of games where players start the game with different sets of options. Think of these terms as a spectrum, rather than merely two buckets.

Symmetric Asymmetric

<————————————->

Same starting options Diverse Starting options

On the left side of the spectrum, we have games like Chess. In Chess, each side starts with exactly the same 16 pieces. The only difference between the two sides is that white moves first. Because of this different starting condition, we shouldn’t say that Chess is 100% symmetric, but it’s damn close. If Chess were the only game you had ever seen, you might think that the black and white sides are played radically differently; white sets the tempo while black reacts. There are entire books written about how to play just the black side. And yet if we zoom out to look at the many games in the world, we see that the two sides of Chess are so similar as to be virtually indistinguishable when compared to two races in Starcraft, two characters in Street Fighter, or two decks in Magic: The Gathering.

The more diversity in starting conditions the game allows, the farther to the right of our spectrum it belongs. So asymmetry, as we mean it here, is a measure of a game’s diversity in starting conditions. This is not meant to be an exact science, so there is no specific formula to determine where a game belongs on this spectrum, but it’s a handy concept anyway.

Let’s look at a few examples. StarCraft has three very diverse races so it belongs toward the right side of our spectrum. That said, even if the three races were as different as imaginable from each other, the number three is small enough that we shouldn’t put it at the far right (admittedly, this is a judgment call). Fighting games can have dozens of characters that play completely differently and they tend to have more asymmetry than most other types of competitive multiplayer games.

That said, individual fighting games can vary quite a bit in just how asymmetric they are. Virtua Fighter, for example, is an excellent and deep fighting game, but the diversity of characters is relatively low compared to other fighting games. All characters have a similar template compared to Street Fighter where some characters have projectiles, or arms that reach across the entire screen, or the ability to fly around the playfield. Meanwhile, Guilty Gear, a fighting game you’ve probably never heard of, has more diversity than any other game in the genre that I know of. One character can create complex formations of pool balls that he bounces against each other, another controls two characters at once, another has a limited number of coins (projectiles) that power up one of his other moves and a strange floating mist that can make that powered up move unblockable. It’s almost as if each character came from a different game entirely, yet somehow they can compete fairly against each other. Guilty Gear is possibly all the way to the right of our chart because it has both wildly different starting options (characters) and many of them (over 20!).

Magic: The Gathering is also extremely asymmetric in the format called constructed where players bring pre-made decks to a tournament. The variety of possible decks is staggering and tournaments usually have several different decks of roughly equal power level, even though they play radically differently.

First-person shooters tend to be very far toward the symmetric side of the spectrum, usually offering the same options to everyone at the start, except for spawning location. Remember that picking up different weapons during gameplay, or even changing classes during gameplay in Team Fortress 2, does not count as asymmetric for our purposes. (Again, because those different options don’t need to be exactly fair against each other.) Also, first-person shooters that do have asymmetric goals for each side often make the sides switch and play another round with roles reversed so that the overall match is symmetric.

Now that we’ve mapped out where some games fit on our spectrum, remember that this is not a measure of game quality. If your favorite games appear on the left (symmetric) side, that does not mean they are bad. If you like StarCraft more than Guilty Gear, you do not need to be upset that Guilty Gear is “more asymmetric.” The spectrum is simply meant to give us an idea about how different the starting options of a game are, not about the depth or fun of the game.

No matter where a game appears on this spectrum, it still needs offer many viable options during gameplay to be balanced. In addition to this, the farther a game is to the right of the spectrum, the more it needs to care about balancing the fairness of the different starting options. In the next part of this series, I’ll talk about how we can design games that make sure to offer enough viable options and in the article after that, I’ll explain how we can attempt to create fairness in those pesky asymmetric games.(Source:sirlin)

上一篇:跨平台工具能否终结手机平台大战?

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号