阐述游戏本土化处理需注意的相关事项

作者:Christian Arno

许多顶级电子游戏公司会聘请专业的本土化人士,这些人不仅负责游戏中文本和对话的翻译,而且还会帮助公司考虑游戏体验中更深的层次,比如角色、故事、文化特有内容以及其他过去未得到重视的电脑游戏体验关键层面。

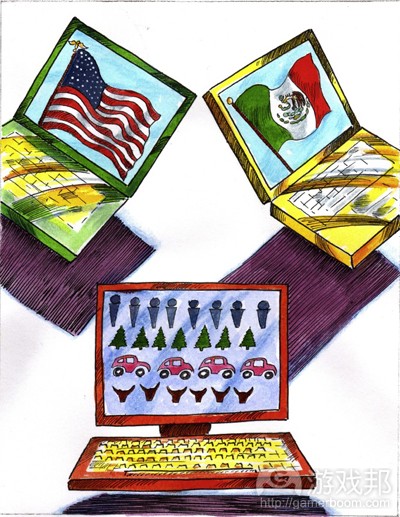

将层次简单化:分离文本和图像层

在开发电脑游戏时,许多设计层面可以预先考虑到国际化的计划。

比如,应当用层面分离文本和艺术内容。此处“层面”的含义与往常电子游戏设计中的含义不同,以往指的是游戏的各个层面,从游戏的基本背景到情节、核心机制、元机制等。

这里所说的“层面”指的是游戏设计和编程的方法。举个例子,网页设计师使用CSS来设计有着不同层面的站点,这一系列不同的层面包含框架、文本、图像和影像。如果设计师需要修改某个图像或某段文字的语言,他们只需要简单地修改页面中的1到2个层次即可,而无需从头开始重新设计整个页面。

在编程和开发游戏时,保持这种层次概念也是很有帮助的。具体的操作方式取决于你所使用的开发软件,但是需要记住游戏中的元素应当支持随意移动和替换,这样在制作本土化版本时可以为你节省时间和金钱。

而且,所有与言语有关的内容应当同视觉或音乐元素独立开来,这样会使得替换成其他语言的过程更加简单。

考虑空间问题

在表达相同信息时,有些语言所需的空间可能比英语少。比如,“information”这个词在日语中只需用两个字就可以表达出来。其他的亚洲语言也是如此。相对比之下,欧洲其他国家的语言会比英语更长些。

由于同一种语言也可以用多种方法来表达同样的内容,所以估算需要为转换的目标语言预留多少空间也是件很难的事情。但是,我们可以总结出哪些语言在表达内容上会比英语更长或更短。

我们先来讨论4中主流欧洲语言:法语、意大利语、德语和西班牙语。

法语通常要比英语长20%左右,意大利语为15%,德语20%,西班牙语25%。因而,尽管德语在语言中以其长度著称,在与英语的长度比较上,它同法语类似。阿拉伯语通常会比英语长上25%。就普遍规律而言,语言长度上英语算是较短的。

日语和汉语在口语上所需的时间较少,但是它们与英语有很显著的差别,因为文字系统完全不同于英语。

从游戏设计的角度上看,分析语言有重大的价值。下拉列表、菜单和其他文字元素的展开或收缩都需要必要的空间,而这个空间的大小取决于所使用的语言。如果能够精确地了解语言空间,就无需担心展开项目是否会覆盖住某些图像,或者出现某些形式的显示误差。

在设计阶段,应当为翻译的目标语言预留足够的空间,包括供用户输入的文字栏、菜单和按键。可行的做法是,努力避免使用“固定大小”的设计,如果某些元素确是需要固定空间,就要补充评论这样翻译者才知道在翻译过程中进行适当的限制。

另一个值得考虑的问题是,许多国家的键盘布局可能有所不同,所以在进行热键编排时应当将此考虑在内。

考虑文化差异

在玩家认知电脑游戏方面,文化扮演着重要的角色。比如,日本游戏更为线性化,但是美国、英国和欧洲国家游戏更倾向于“沙盘化”。

社交游戏通常属于“横向”应用,也就是说说社交游戏是种适合所有人玩的游戏,从你的好友到你的母亲,任何年龄段的玩家均可体验。社交游戏的“纵向”行业仍处在发展中,也就是针对特别群体玩家诉求而设计的游戏。

但是,即便是“横向”的社交游戏,在进行游戏本土化时,文化问题的考虑也是至关重要的。Zynga在Facebook上有两款最为流行的社交游戏,它们是《FarmVille》和《CityVille》,它们已经通过本土化面向世界其他用户开放。《CityVille》进行了欧洲国家其他语言的本土化,《FarmVille》进行了汉语本土化,本土化几乎重新构建了整款游戏。

这个本土化过程设计到文化上的问题,包括将颜色变得更为明亮,增加了农场地块的面积,以满足中国审美和文化体验。

诸如《FarmVille》这种内容相对健康的游戏都需要考虑到如此多的文化事宜,那么像《Mafia Wars》之类富有争议的游戏就要面临更多的挑战,因为这些游戏中有暴力和毒品交易的内容。

在考虑文化问题时,除了移除那些提及性、毒品和暴力的内容外,你还应当注意游戏中使用的图标,因为图标的含义可能在全球各地有很大的差异。比如,在西方国家里,“翘大拇指”意味着赞许。但是,在有些地方,这却是种挑衅的手势。

其他需要考虑的问题

现在我们很清楚,应用和游戏本土化所涉及的不仅仅是语言上的转换。还需要考虑其他的问题,日期、数字、货币和度量衡都应当转化成恰当的形式。

在英国,“英里”和“英镑”仍然广泛使用,也能够被玩家所理解。但是如果将游戏本土化到欧洲其他国家,这些单位就要进行转换。

如果有些地方需要用户输入内容,那么形式应当足够灵活,可以转变以适合各地区的需要,比如邮政编码和地址形式。

认清这些问题对项目计划很有帮助。即便你目前没有将游戏本土化到其他市场的意图,细心考量当前目标市场也是很有价值的,将这些内容运用到游戏和应用设计汇总。

作为游戏开发者,你可能无法取悦来自所有文化的玩家,让游戏完全满足全球玩家的诉求也是不实际或成本过高的想法,有些游戏在某些国家获得的成功可能要比其他国家更高。但是,进行此类计划可最大化跨文化传播的成功率。

国际化成本

当然,合适的本土化需要成本,成本的多寡取决于需要修改的内容和质量。

如果你已经遵循了以上所有步骤,剩下的事情之时将文字本土化成其他语言,那么成本的多寡就在于翻译费用。翻译费用根据语言和国家的不同而不同,但是我可以提供大概的费用范围:

1、英语翻译成法语、意大利语、德语和西班牙语:每1000个单词160-275美元

2、英语翻译成丹麦语、荷兰语、芬兰语、冰岛语、日语、韩语、挪威语和瑞士语:每1000个单词190-325美元

转变成其他语言的成本与上述成本相近,额外的语言结合可能会提升翻译价格(游戏邦注:比如,两种非常用语言之间的转换成本会高点)。

除了翻译成本外,还有相关的文件管理和DTP成本,这些通常是以每小时为单位来收费的。根据所使用的技术不同,这项成本在每小时75-150美元。

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2011年2月4日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Localization Is More Than a Game

Christian Arno

Japan was always at the forefront of the console and computer gaming industry, with the likes of Nintendo and Sega having their main headquarters in Kyoto and Tokyo respectively.

But with the popularity of computer games growing exponentially over the past couple of decades, there has been a slight shift away from the Japan-centric video game industry, with many of the top publishers and developers now based across the world – such as EA (US) and Rockstar North (UK).

Many of the top video game companies use the services of dedicated localization specialists, who not only arrange for the translation and interpretation of the text and dialogue, but also help them to consider the subtler aspects of the gaming experience: the characters, the story, culture-specific points of reference – key aspects of a computer gaming experience that have often been more of an after-thought in the past.

Layers of simplicity: keep text and graphics separate

When developing a computer game, many of the design aspects can be planned with one eye on adapting the game at a later stage for international audiences.

Layers, for example, should be used to help keep text and artwork separate. The term ‘layers’, in this instance, does not carry the same meaning as it usually does in video game design, which is the various layers of the game, from its basic setting to its plot, core mechanics, meta mechanics, etc.

Rather, ‘layers’ in this instance refers to way the game is designed and programmed. As an example, a website designer might use CSS to design a site with different layers – the framework, text, graphics and images would consist of a series of different layers. This way if the designer needs to change an image or change the language of a piece of text, they need simply change one or two layers, rather than redesign the page from scratch.

As such, when programming and developing a game, it helps to keep this concept of layers in mind. Exactly how you would go about this will depend upon the development software you’re using, but keeping in mind that elements of the game may need to be slotted in and out, like a Rubik’s Cube, for various localized versions will save you time and money down the line.

Additionally, any vocals and voiceovers should be kept separate from the visual or musical elements, meaning that separate vocals can be recorded and included in the game with ease.

Space considerations

Some languages require less space than English to express a message. The word ‘information’, for example, needs only two characters in Japanese. The same is the case with many Asian languages. In contrast, European languages tend to be longer than English.

The specifics of how much more/less space one language needs over another is difficult to convey, given that there are 101 ways of saying something in many languages. However, it’s possible to give some general direction on which languages are typically longer/shorter than English.

Let’s start with the four main European languages: French, Italian, German and Spanish (FIGS).

French is generally longer than English by anything up to 20%, whilst Italian requires about 15% more space, German 20% and Spanish 25%. So whilst German has a reputation for being a particularly ‘long’ language, it is about the same as French when compared to English. And Arabic is typically about 25% longer than English. As a general rule, English is at the lower end of the language-length spectrum.

In terms of tongues requiring less space, Japanese and Chinese generally consume less room, but it really does vary quite a lot as the writing system is completely different to English.

From a game design perspective, this has massive implications. Dropdown lists, menus and other textual elements will require the necessary space to grow or shrink depending on the language, without worrying whether it will overlap a graphic or if it will in some way be displayed incorrectly.

In the design phase, enough space should be allowed for translated text, including any text-boxes for user-input, menus and buttons. Where feasible, try to avoid ‘static sizing’ and if some elements do require strings of a set size, include a comment to this effect so that translators know the limitations during the translation process.

Another point worth considering is that the layouts on many international keyboards differ, so this should be taken into account with hotkey mapping.

Cultural considerations

Culture plays a massive part in how someone perceives a computer game. In Japan, for example, games have a tendency to be rather linear, whereas in the US, UK and across Europe, games have gravitated towards a more ‘sandbox’ style of game.

Social games are typically ‘horizontal’ applications – in that many social games are the sort of games that everyone enjoys playing, from your friends to your mum to your boss. The ‘vertical’ industry in social gaming – i.e. games designed to appeal to a specific demographic – is still developing.

However, even with ‘horizontal’ social games, it’s important to take into account cultural considerations when undertaking the localization of a game. Zynga, which can lay claim to the two most popular social games on Facebook – FarmVille and CityVille – has recently localized both games for international audiences, and while CityVille has seen only localization for European languages, FarmVille has been localized for China, which involved rebuilding the game from the ground up.

This localization process involved taking into account cultural considerations including changing the color palette to be brighter and increasing the size of the farm plots, to appeal to Chinese aesthetics and cultural experience.

With a fairly innocuous game such as FarmVille, you can imagine that the cultural considerations in localization would have been fairly mild, but with a more controversial social game such as Mafia Wars, which involves such nefarious dealings as violence, swearing and drug dealing, the cultural considerations for localization would be significantly larger, especially for a country such as China, where the government has declared increased regulation of online games.

Beyond cultural considerations such as the appropriateness of references to sex, drugs and violence, however, you should also be careful of gestures/icons you use in your game, as meanings can vary across the globe. To illustrate this point, a ‘thumbs-up’ means ‘OK’ or ‘fine’ in the west. However, in other regions of the world a ‘thumbs-up’ hand gesture can be offensive.

Other considerations

So, it’s clear that app and game localization involves more than simply getting the language right. Other considerations include getting formats correct with dates, numbers, currencies, weights and measures.

Whilst the UK is technically metric, ‘miles’ and ‘pounds’ are still widely used and understood, so a US developer would probably be fine leaving such units of measurement in place. But when localizing for elsewhere in Europe then unit conversion would be necessary.

And if user input is required anywhere, then forms should be flexible enough to cater for subtle regional nuances, such as zip codes/post codes and address formats of a specific country or region.

With that in mind, it can be useful to plan well in advance. Even if you have no immediate intention of localizing a game for other markets, it may be worth thinking what countries you would like to target, and factor this into the original game/app design.

As a game developer, you probably won’t be able to cater for all cultural tastes, and it will often be too impractical or expensive to completely overhaul your game for other audiences – some games will simply be more successful in some countries than others. But thorough planning will help maximize the chances of cross-cultural success.

Going local: costs?

Of course, proper localization will probably cost you at least some money – how much depends on how much is required and how professional you want it.

If you’ve followed all the steps above and it’s literally just a case of localizing the text for other languages, then the charges will more or less be the translation costs. Again, these vary from language-to-language and by company, but here are some ball-park figures for translation – and always check that they include full project management costs:

• English to French, Italian, German and Spanish: $160-$275 per 1,000 words (depending on the type of text and the expertise required from the translator)

• English to: Danish, Dutch, Finnish, Icelandic, Japanese, Korean, Norwegian and Swedish: $190-$325 (same conditions as above)

Other languages are in a similar ballpark to the languages above and the price will vary depending on the exact language combination (e.g. translations between two unusual languages, one of which isn’t English, may cost a bit more).

In addition to the translation costs, there may be associated file-management and DTP costs attached, these are normally charged per-hour. Again, depending on the nature of the technical requirements, these could be anywhere between $75 and $150 per hour. (Source: Inside Social Games)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号