解析成长类型及情感元素在游戏设计中的运用

作者:Tony Ventrice

成长

成长描述的是一种拥有方向和前进的感觉。它是人类的一项基本内容,我们长大成人的首要挑战,中年危机的普遍来源。你问小孩他们长大后想干什么,相当于是在问他们的未来规划,人生方向。等到你步入暮年之时,回顾自己的过去,就会因自己的成就而获得满足感。这些成就始于何时,终于何处?当我们之前所谈的理想都一一实现时,我们的整个人生就可以归纳为一个成长的故事。(请点击此处查看本系列第一、第三、第四)

成长类型

孩子

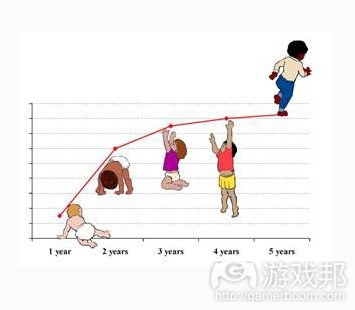

对孩子们来说,成长包括身体上的生长,他们逐渐获得成人特权和承担责任,发展为“健全”而有用的成人。

成人

那么孩子长大成人之后呢?成长这个词的定义在这里又有什么变化?对成人而言,成长究竟有何含义?

孩子在年幼之时,就已经通过其他形式补充自己的实体成长过程——例如扩展知识面,取得一系列成就,逐步掌握相关秩序,建立好友人脉。在身体停止成长的时候,我们就了解了基本的社会规则,这种对生活其他层面的追求将引导我们度过余生。

从许多方面来看,这些其他形式的成长不但创造了个人追求的动机,而且还是构筑社会的基石。我们对学习的渴望有助于解决问题,追求竞争可让我们超越自我并找到最优策略,对秩序的渴望促使我们采取维持和保护行动,而人际交往则让我们彼此紧密联系在一起。

多数人都不会分门别类地记录自己的成就,而我们也确实还没有衡量成就的通用标准,但我相信自己列举的四种方法极具普适性,我认为基本的成人成长类型包括:

·学习

·秩序

·克服挑战

·人际关系

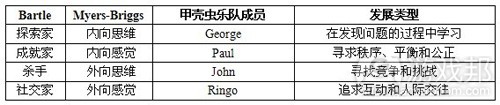

这四种成长类型让我想起Bartle玩家类型、Myers-Briggs人格类型等其他人格分类系统。这些人格分类系统能否指出不同人所追求的成长类型?

尽管这种分类法有助于我们了解不同人的差异,但从属性和原型来看,这种分类法可能存在一定导误性(例如,以甲壳虫乐队为例,使其四个成员对号入座)。若从属性层面上看,我们确实清楚这种分类法只是针对个体的差异性而言,但如果考虑到动机因素,它很容易让人误以为这些“类型”适用于所有人。换句话说,每个个体都有可能比其他人更明显具备某项特征,不过从一定角度上来讲,这些分类对所有人来说都有一定参照价值。

不同情境下的四种成长类型

学习。学习来自对规则系统的理解。通常而言,这相当于一种反复试验的过程:先是形成假设,然后在游戏环境中对其进行试验。

以《街头霸王2》为例,玩家首先要学习如何移动,然后才会发现有效的连击动作,最后就是找到使用这些策略的最佳时机。

虽然学习的目的是让人们得到竞争优势,但其本身也可以令人愉快,让人乐在其中。为何桥牌游戏如此受欢迎?这是不是与它总能让人获得更多学习的乐趣有关?

秩序。这个词看似一种奇怪的成长定义,但我认为如果从规则的角度来看,我们更容易理解其含义。

人们通常都相信生活有其内在意义,而实现这一目标就要求社会存在某些隐性规则——正确概念及错误行为。从个人发展层面来看,秩序代表人们走正道的追求。

在多数电子游戏中,追求秩序的动机产生于因遵守规则而得到奖励,例如收集道具,完成任务和晋级。那些追求秩序的玩家喜欢体验规则明确,并且以遵守规则为获胜条件的游戏。他们希望系统运行有规律,带领他们向更高级的目标或状态前进。

克服挑战。有人推崇秩序,也有人追求混乱。生活时时充满挑战,人类必须学会应对逆境以获得生存。虽然这种过程很刺激,但也可能很痛苦和让人不快。在现实生活中,有许多无法克服的挑战最后总是让我们很受挫。

而游戏所提供的总是我们能够克服的挑战,若非如此,其设计必定存在严重的问题。但平衡这种挑战性却并非易事:游戏太容易就会失去挑战性,太困难就会让人受挫。挑战型的玩家需要的是一种挑战和胜利的良性循环。

人际交往。正如多恩(游戏邦注:英国16世纪神学家兼诗人)所言,没有谁能像一座孤岛一样在大海里独踞。与他人交往和联络感情的需求深深扎根于我们生活的方方面面,这种需求是人类文明和社会的基础。

在游戏中,社交成长主要体现为相互依赖——有人需要你的帮助,你也离不开他人。从《魔兽世界》中的公会到《CityVille》中的交换礼物等现象均可以看出,双方的这种依赖性越深,就越能够让社交型玩家获得许多回报。

在设计中植入成长机制

为了研究如何将成长植入非游戏环境,我们要先谈谈每种成长类型的适用情境。

植入学习机制。学习需要一套规则系统,任何系统都能满足这个条件,但很显然,规则越是微妙和精细,就越能支撑长期的学习机制。

但不幸的是,我们还要考虑学习曲线这个额外的复杂因素。不同玩家的学习进度不一样,如果不想让游戏流失用户,就必须提供富有弹性的学习机制。理想的学习曲线应该提供简单的交互层,但同时又具备深度发展的空间(游戏邦注:这里指策略、规则变化等)。

总体上看,你不需要为添加学习机制而设计游戏,而是要用设计来管理游戏已经具备的学习机制。要简化必要的学习机制,同时为更高级的用户设置具有一定难度的“终极游戏”目标。

另外,挑战性和游戏中的琐事如果处理得当,也可以具有娱乐性并辅助学习过程。

植入秩序元素。秩序正是将徽章、奖杯以及当前的“游戏化”概念,把游戏与非游戏体验衔接起来的元素。基于徽章的系统并非新鲜事物,小孩因提交家庭作业而获得金星,军官接受别在肩上的臂章,这些奖励都具有相同的属性。

为强化其意义,我们可以用象征性的符号来纪念重要经历,而微章又可与奖励或特权相联系。例如,金星也许可以让孩子获得糖果奖励,而臂章可以提高军官等级,增加他们掌握的实权。

植入克服挑战系统。我们在这里所讲述的是战胜敌对势力。玩家希望体会到强大和重要之感,他们希望自己的成就独特非凡。

但从实际逻辑上看,大家都知道让所有人都与众不同是不可能的。在单人游戏体验中,玩家的个人表现没有其他参照标准,这并不是什么问题,因为这类游戏并不一定要体现胜利的大小。只要让游戏充满挑战性即可,没有人会质疑这一点。

我认为比起其他元素,这种克服挑战的系统正是传统电子游戏延续至今的主要趣味所在。

在社交环境中,玩家可以比较游戏进程,他们不会过于重视成就的大小。假如我完成了一项艰难的挑战,结果却发现多数人更省时省力地取得了同样的成绩,那么我获得成就的趣味感可能就会因此而荡然无存。

为了维持玩家的胜利感,我们设计游戏时需要采取更复杂的策略。例如定制多种胜利结果,或者简单地避开这个问题,让参与竞争的双手都误认为自己赢了(游戏邦注:作者认为《Empires and Allies》就是这方面的典型)。

如果这种欺骗性的做法不受欢迎,那么最佳选择可能就是将单人体验和社交挑战结合在一起,利用许多非竞争性的胜利元素吸引玩家,将他们引向更有难度、更具社交挑战性的胜利顶点。最具竞争意识的成就型玩家一般都喜欢追求远大的目标。

植入社交成长意识。促进玩家的社交成长需要满足一些条件。首先,游戏中要有能够让玩家交流与合作的场所。如果玩家不能以富有意义的方式彼此交谈和互动,他们就不可能产生社交联系。

其次,游戏中要创造特定语境,社交目标或者至少一个对话起点。

第三,这种社交成长必须具有持续性。要支持玩家反复联系相同的人。

Facebook等社交网络可谓将这三个要素诠释得淋漓尽致,涂鸦墙贴子、消息、标签和评论等构成了用户交流的场所,状态更新和分享功能创造了交流的语境,而社交网络本身就是保持联系的体现。

内在激励因素

情感是一个含义模糊的话题,在定义其趣味构成之前,我们有必要进一步探讨其意义。

笛卡尔(法国数学家、哲学家)、霍布斯(英国哲学家)等哲人早已列出“主要”的情感类型,这些情感列表基本上各有特点。

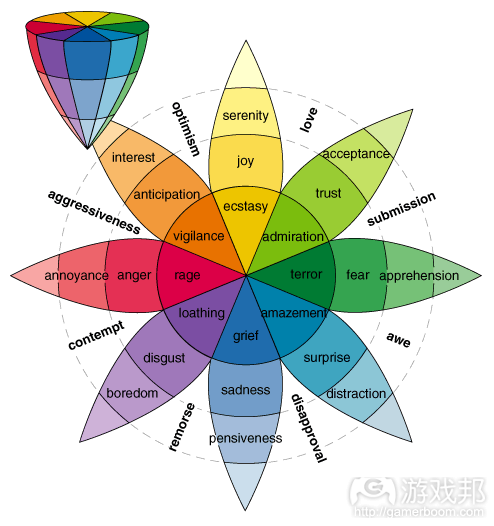

情感领域的思想家Robert Plutchik制作了一个具有8个点,4个组合的模型:愤怒–恐惧,期望–意外,快乐–悲伤,欣赏–厌恶。

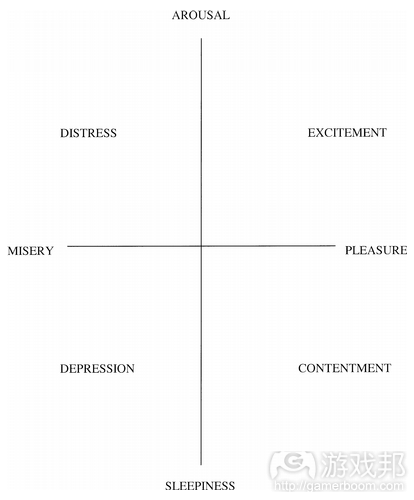

James Russell则提出了一个更具逻辑性的模型,他绘制的二维图表中分布着8种情感,纵轴是觉醒–沉睡,横轴是快乐–痛苦。兴奋、满足、沮丧、悲伤则顺时针分布于这四个象限之间。

Russell这个模型将所有情感纳入觉醒–沉睡,快乐–痛苦的范畴,可以算是一个较有衡量性的系统。

虽然我不认为Russell的这个模型有何问题,但它所描述的情感类型却并非我们研究的方向。Russell所归纳的是较为原始的,连爬虫动物都有的情感,但它并不能解释政治讽刺文学或惊悚小说的魅力所在。

自人类载史以来,我们认为有趣的内容几乎都有个一致的模板:体裁。有趣的是,多数体裁都会与特定的情感挂钩,例如悬念、爱情、喜剧、恐怖、历险、戏剧和悲剧。尽管这并没有全面覆盖人类情感类型,但它确实已包含我们所述的与娱乐相关的所有情感。

与娱乐相关的情感

游戏设计经常把多种情感交织成复杂的故事,但为了便于理解,我们将使用最简单的例子对这些情感逐个进行解析。

悬念(或惊悚)或许是游戏中最常见的情感类型,此类游戏通常会设置未知的结果。完全采用悬念元素的游戏包括《Water-balloon Toss》、《Crocodile Dentist》和《Don’t Wake Daddy》。

除此之外,带有紧张感的游戏通常也包含悬念元素,例如儿童在暗室所玩的捉迷藏游戏、纸牌游戏Slap-Jack以及恐怖生存游戏(这些游戏中常有一些怪物冷不防地从玩家毫无防备的方向跳出来)。

爱情也常与悬念相联系。这方面的例子包括日本恋爱模拟游戏《神秘约会》,转瓶游戏和脱衣扑克。有些人可能会认为调情和约会是配对游戏中的一个环节,我认为在线社交游戏中的性紧张现象也可以划入这个范畴(例如《Zynga Poker》中就有许多用户调情行为)。

喜剧是《Taboo》、《Once Upon a Time》、《Balderdash》和《Apples to Apples》等许多创意派对游戏的主要目标。《Balderdash》和《Apples to Apples》这两者甚至还通过投票机制奖励那些最搞笑的玩家。

但这些游戏的规则中却并不含喜剧元素,只有当玩家在特定语境下自由表达时才可能会碰撞出喜剧的火花。另外,你在Facebook涂鸦墙上也经常可以看到好友的妙语和小笑话。

恐惧作为一种娱乐元素时,通常得能够让用户产生恶心和害怕之感。恐怖游戏通常从包装和名称中就能体现出来,例如《FEAR》、《生化危机》、《生化奇兵》和《死亡空间》。

冒险元素贯穿于每款拥有一个故事主角的游戏。玩家在冒险游戏中要战胜逆境,逃脱死亡,争分夺秒。从许多方面来看,冒险题材的游戏通常也涉及其他多种情感,带有一点惊悚、恐怖、喜剧、悬念甚至爱情元素。但它对这些情感的涉猎并不深,也许正是这种平衡性让冒险游戏拥有如此魅力,并且难以被其他简单的非游戏体验所复制。

戏剧是一个含义广泛的词。戏剧还包含一系列上文未曾提及的情感,例如嫉妒、怀疑、恐惧、内疚、野心、厌倦和抑郁等。

游戏的故事情节也常运用戏剧元素(JRPG游戏最为典型),但在实际玩法中,游戏会更侧重怀疑和野心等竞争性层面。多人游戏通常会对竞争和协作的平衡性提出要求,《Avalon Hill’s Diplomacy》就是巧妙结合信任、恐惧和内疚等戏剧元素的少数典型代表之一。

悲剧看起来像是最不具有代表性的情感类型,只有少数游戏会专门采用这种元素(游戏邦注:例如《旺达与巨像》和《剑与魔杖》,这两者都采用微妙的悲剧元素)。

为了制造悲剧,游戏必须具有失败的结局,但失败并非多数游戏设计所考虑的选择。

情感是一种难以植入游戏中的元素,除了在传统的游戏叙事方式中发挥作用,它通常并非游戏设计所追求的明确目标。如果要将情感作为游戏玩法的目标,我认为可以参考以下三种游戏设计中的情感归类方式:

悬念——最适合传统游戏机制

爱情、喜剧、戏剧——如果考虑周全,在游戏设计中会很管用

恐怖、冒险、悲剧——仅适合含有故事元素的情境

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Gamification Dynamics: Growth And Emotion

by Tony Ventrice

[In the first installment of this series, Badgeville's Tony Ventrice looked to frame the discussion around what's possible with gamification by attempting to discover what makes games fun. In this article, Ventrice delves into the first two of his seven identified dynamics of game design.]

Growth

Growth describes a sense of direction and progress. It is a fundamental aspect of humanity, the first great challenge of adulthood, and a typical source of midlife crisis. When you ask a child what they want to be when they grow up, you’re asking about their plan, their direction for life. When, old and shrunken, you look back

over your life, satisfaction lies in what you’ve accomplished. Where did you start and where did you end up? When all is said and done, our entire existence is summed up as a story of growth.

Types of Growth

Growth comes in different guises, and depending on what you value and where you are in life, the ways in which you seek and measure growth will be different.

Children

For children, growth is literal: from the physical growth of their bodies to their gradual accumulation of adult privilege and responsibility, they are effectively growing to become “complete” and functioning adults.

Adults

But what happens when a child is all grown up? How does the definition of the word change? What is the meaning of growth for adults?

Even from a young age, children begin to supplement their literal growth with other forms — things like an expansion of knowledge, a record of accomplishments, an accumulation of order, and a network of friends. Once the body stops growing, and the basic rules of society are understood, the pursuit of these other dimensions continues, guiding us through the rest of our lives.

Not only do these other forms of growth provide individual motivation, they are, in many ways, the underpinning of our societies. Our desire for learning solves problems; our desire for competition challenges stagnation and finds optimizations; our desire for order preserves and protects; and our desire for connections promotes cooperation and bonds us together.

Now, most people probably never catalog their accomplishments by category, and there’s certainly no universally recognized list of measures, but I believe the four I’ve listed are fairly comprehensive — and if you bear with me a little longer, I’ll try to illustrate why.

The four basic types of adult growth:

•learning

•order

•challenges overcome

•connections

A Realization

While thinking about the measures of growth, I realized the list I was making resembled some other lists I’ve seen before — namely the Bartle test, the Myers-Briggs personality type indicator, the four humors of antiquity, or really any other form of personality classification system. Yet these systems tend to focus on determining personality types. Could it be that they also identify the general preferences along which people strive for growth?

Bartle

Meyers-Briggs simplification

Beatle

Growth preferences

Explorers

Thinking Introverts

George

seek questions and learning

Achievers

Feeling Introverts

Paul

seek order, balance and validation

Killers

Thinking Extroverts

John

seek competition and challenges

Socializers

Feeling Extroverts

Ringo

seek interactions and connections

While useful to understanding possible differences between individuals, I think these designations have always been potentially misleading when thought of as attributes or archetypes (such as the implication of the Beatles example). As attributes, there is a tendency to think only in terms of differences, but when considered as motivations, it’s easier to think of these four “types” as actually being present to varying degrees in all humans. In other words, an individual probably values one form of growth more than another but ultimately they’re all valuable, in some degree, to everyone.

Four Types of Growth, in Context

How do these four forms of growth manifest in game design?

Learning. Learning comes from deciphering the rules of a system. Typically, this follows a pattern of trial and error, forming hypotheses and testing them within the game environment.

To take a game like Street Fighter II as an example, the learning is in first mastering each move, then discovering effective combos, and finally identifying the best situational opportunities in which to use them.

Although learning is a means towards a competitive edge, it can also be a pleasurable end in itself; learning simply for the sake of the process. Why is the card game Bridge so widely appealing? Is it because there is always something more to learn?

Order. Order may seem like an odd way of defining growth, but I think it makes more sense if thought of from the perspective of rules.

There is a basic human desire to believe life has meaning and purpose and for this to be true, there must be implicit rules — concepts of correct and incorrect behavior. As a dimension of personal growth, order represents pursuit of following the correct path, however the individual may choose to define it.

In most video games, the motivation of order boils down to the act of following rules for rewards: collecting sets, completing tasks and leveling up. Those who seek order desire situations where the rules are clear and simple adherence is all that is needed to succeed. They prefer frequent and literal validation that the system functions and that it is guiding them towards a greater objective or higher status.

Challenges Overcome. If some thrive in order, others thrive in chaos. Life is constantly challenging and humans must adapt to survive against adversity. While the process may be exhilarating, it can also be painful and unpleasant; in real life, many challenges cannot be overcome at all, leading to discouragement.

Games offer a pleasant escape in that the challenges they present are almost always surmountable. In fact, if they aren’t, your design probably has a serious problem.

The difficulty with implementing challenge comes in the balance: too easy and it’s not challenging, too hard and it’s discouraging. Challenge-driven players need a regular cycle of challenge and success.

Connections. As Donne wrote, no man is an island. Making connections and sustaining relationships is deeply ingrained in all spheres of our lives and underlies our very concepts of civilization and society.

In games, social growth manifests as interdependencies — people who need you and people you need. From World of Warcraft raids to CityVille gift exchanges, the more connections and the deeper the dependencies, the more rewarding the experience will be to the socially-driven player.

Putting it in Practice

To investigate how growth might be integrated into a non-game environment, we’ll look at each motivator in a general context.

Implementing Learning. Learning requires only a system of rules. Any system could suffice, but obviously the more nuanced and subtly deep, the longer learning will be sustained.

Game Advertising Online

Unfortunately, there is an additional complication: the learning curve. Different users learn at different rates, and if you don’t want to lose audience, the learning needs to accommodate a flexible rate of uptake. An ideal learning curve provides a simple basic layer of interaction with the opportunity for deeper emergent layers (strategies, situational rule changes, etc).

In general, you do not need to design to add learning; you need to design to manage the learning you already have. Try to simplify the required learning and push complexity into “end game” objectives for your more advanced users.

Supplementally, challenges and game trivia can be entertaining and validating for the learning process, if handled unobtrusively.

Implementing Order. This is where badges, trophies, and the current idea of “gamification” has already bridged the span from game to non-game experiences. Badge-based systems are not new; from children receiving gold stars for turning in their homework to military officers receiving chevrons on their shoulders, they are a familiar construct.

Any meaningful experience can be commemorated with symbolic measures and, for additional validation, badges can be linked to rewards or privileges. For example, gold stars might result in candy bars, while chevrons bring rank an increased chain of command.

Implementing Challenges Overcome. Here we’re talking about the goal of overcoming opposition. The user wants feel magnitude and relevance — that his accomplishments are rare and special.

Yet in reality it’s logistically impossible for everyone to be exceptional. In a solo experience, where the player has no frame of reference as to how other players are doing, this isn’t a problem, as it’s not necessary to prove the magnitude of a victory. The game feels challenging, and there is no reason to think that it isn’t.

I’d say this sense of challenges overcome is the one thing, more than any other, traditional video games have relied on for fun so far.

In social environments, where players can compare progress, the weight of accomplishments may be devalued. If I complete a difficult challenge only to discover that most people achieved the same result in less time or fewer attempts, much of the fun of the accomplishment is lost.

To maintain the illusion, more complex strategies are needed. Strategies such as ‘framing’ victory (you’re the best over-forty, overtime, free-throw shooter) or simply sidestepping the problem entirely with misleading implications, such as letting both players in a competition think they’re winning (I’m looking at you, Empires and Allies).

If deception isn’t desirable, the best option is probably a mixed approach of solo and social challenges, with lots of little non-competitive victories to get users hooked, leading up to harder, more socially-contestable victories at the top: aspirational objectives to keep the most competitive achievers engaged.

Implementing Social Growth. There are a few provisions needed to foster social growth. First, there need to be venues of communication and collaboration. If players can’t talk to each other and interact in any meaningful manner, there’s no opportunity to make social connections.

Second, there needs to be a context, a social objective or at least a conversation starter.

Third, there needs to be persistence. Players need to be able to reconnect with the same people.

It should come as no surprise that these three are perhaps most clearly demonstrated by social networks, such as Facebook. Wall posts, messages, tags and comments constitute venues of communication, status updates and shares constitute context and the network itself represents persistent connections.

Intrinsic Motivators

When viewed collectively, the four motivations of growth often comprise a player’s most basic intrinsic motivations — motivations that the player carries with him into every context, be it a game, a job or an evening with friends. These are the motivations that, when actualized, are central to providing the long-term interest that keeps people engaged.

Emotion

Emotion is potentially a vague or equivocal topic and worthy of a little investigation before we dive right in to defining what makes it fun.

Enlightened thinkers have been making lists of “primary” emotions for a long time, with some well-known names including Descartes and Hobbes. And while lists are interesting, typically, they haven’t agreed on much beyond the fact that humans experience pleasure, pain, and some other stuff.

Fast-forwarding to the present, the situation doesn’t seem to have changed much. Robert Plutchik [PDF link], who is something of a thought leader in the field of emotion, has created an eight-point wheel with four spokes: Anger-Terror, Anticipation-Surprise, Joy-Sadness, and Admiration-Loathing. Plutchik made some questionable choices with his model, like using two dimensions to represent four, placing the axis extremities in the center, and suggesting the whole thing be folded to form a cone.

Probably as no surprise, Plutchik’s model largely results in nonsense when you try to put it to practical use — where might I place jealousy? Pride? Lust? Pity?

James Russell [PDF link] proposed an alternate model with a much more logical method. His “circumplex” plots eight basic emotions on a two dimensional graph with Arousal to Sleepiness along one axis and Pleasure to Misery along the other. Excitement, Contentment, Depression and Distress are situated in the quadrants between.

By limiting all emotion to an arousal scale and a pleasure scale, he at least proposes a measurable system.

While I don’t believe there is anything wrong with Russell’s model, it seems to be describing a different kind of emotion than the kind we’re looking for. Russell’s emotion is the primitive kind, the kind reptiles have, and not exactly the kind that is going to explain the appeal of a political satire or a taut thriller.

The fact seems to be, if we want a practical definition beyond a simple measure of pleasure and pain, our science has yet to provide. Fortunately for this investigation, there may be a way of approaching the question from another direction.

Since the dawn of recorded history, the stories we find entertaining have followed a consistent template: genres. And the interesting thing about genres is most of them happen to coincide directly with specific emotions: Suspense, Romance, Comedy, Horror, Adventure, Drama and Tragedy. While this isn’t a comprehensive list of human emotion, it does appear to be a comprehensive list of emotions we explicitly seek for entertainment.

The Emotions of Entertainment

In game design, multiple emotions often turn up woven together in complex stories, but for our purposes we’ll attempt to address them in isolation, as part of the game experience itself, using the simplest, most pure examples possible.

Suspense (or Thriller) is perhaps the most common emotion in games, and turns up in any game with an uncertain outcome. An entire genre of kids’ games (that I like to call “Russian Roulette games”) is based entirely on suspense and includes the Water-balloon Toss, Crocodile Dentist, and Don’t Wake Daddy.

But more than these, any games that build on anxiety contain suspense, such as children playing hide and seek in a dark house, the card game Slap-Jack, and the aspect of survival horror games in which monsters spring on you from unexpected directions.

Romance has a few representatives that often share duty with suspense; Mystery Date is a weak example, as are likely those dating simulators sold in Japan.

Less vicarious examples include spin the bottle and strip poker; some would argue actual flirting and dating are part of a ritualistic mating game. I would also add that situations where sexual tension might develop in online social games should count (I certainly saw plenty of flirting when I was working on Zynga’s poker.)

Comedy is clearly a driving objective of many creativity-based party games like Taboo, Once Upon a Time, Balderdash, and Apples to Apples. The latter two even directly reward humor via voting mechanics.

Yet you probably won’t find more than a passing mention of comedy in these game’s rules; comedy instead seems to be an emotion just waiting to happen anywhere players are given the context to express themselves in a free format. As evidence, you probably don’t have to look any further than the activity of your friends on your Facebook wall to find a series of quips and one-liners.

Horror as entertainment requires a certain terrifying visceral experience that aims to instill disgust and build a sense of dread. While gladiatorial combat was probably quite the spectacle in its time, in the modern era horror as entertainment is largely limited to pure narrative fantasy. Horror games are usually clearly packaged, including the likes of FEAR, Resident Evil, BioShock and Dead Space.

Adventure covers just about every video game featuring a protagonist ever made. The player overcomes adversaries, cheats death, and races against time. In a lot of ways, adventure sits at the intersection of many of the other emotional genres; a little bit thriller, horror, comedy, suspense, and even romance. It covers none of these emotions too deeply, and perhaps this balance is what makes an adventure so universally appealing (and so unlikely to be obtained in simple non-game experiences).

Drama is something of an umbrella term. Dramas tend to cover a range of emotions not already mentioned; things like jealousy, suspicion, honor, guilt, greed, ambition, ennui, and repression. Collectively, they seem to describe interpersonal relations taken to dysfunctional extremes.

Game stories certainly take advantage of drama regularly (any JRPG), but in actual gameplay, games tend to rely on the more competitive aspects like suspicion and ambition. Multiplayer games that require balancing competition and cooperation, like Avalon Hill’s Diplomacy, represent the rare few that accurately model the emotional strain of shifting trust, honor and guilt of real drama.

Tragedy seems to be the least-represented emotional genre, with only the rare game dedicated to it (Shadow of the Colossus and Sword and Sworcery are two examples and both play tragedy with subtlety).

But this should be expected: to constitute a tragedy, the experience must ultimately be a failure, and failure is not a satisfactory outcome in most game designs. Although it is worth observing that, in most multiplayer games, everyone but the winner ultimately fails, and that in itself is something of a controlled tragedy.

Emotion is a difficult element to instill into games. It tends to be highly contextual and not usually pursued as an explicit objective beyond the scope of traditional story-telling. When considering emotion as a gameplay objective, I think it’s beneficial to view the available emotions in three groups of utility:

Those that integrate well with traditional game mechanics: Suspense

Those that can be worked into a design, if the proper considerations are taken: Romance, Comedy, Drama

Those that really only work in the context of a story: Horror, Adventure, Tragedy(source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号